Abstract

Objective

To describe the design of a longitudinal study of youth with elevated symptoms of mania (ESM) as well as the prevalence and correlates of manic symptoms. Bipolar disorder in youth is serious and is surrounded by controversy about its phenomenology, course and treatment. Yet, there are no longitudinal studies of youth selected only for ESM, the phenomenological hallmark. The study’s objective is to document the rate and sociodemographic correlates of ESM in children attending outpatient psychiatric clinics.

Method

Parents of 3329 6–12 year old children visiting 10 outpatient clinics were asked to complete the Parent General Behavior Inventory-10 Item Mania Scale (PGBI-10M). Children with PGBI-10M scores ≥ 12 (ESM+) and a matched sample of screen negatives (ESM−) were invited to enroll in the longitudinal study.

Results

Most (N=2622, 78.8%) participated. Nonparticipants were slightly younger (M=9.1 years, SD=2.0 versus 9.4 years, SD=2.0; t=4.42, df=3327, p<0.001). Nearly half (43%) were ESM+; these were more likely to be Latino (4.2% versus 2.5%, X2 =5.45, df=1, p=0.02), younger (M=9.3 years, SD=2.0 versus M=9.6 years, SD=1.9, t=3.8, df=2620, p<0.001) and insured by Medicaid (48.4% versus 35.4%, X2 =45.00, df=1, p<0.001). There were no sociodemographic differences between those who did versus did not agree to enroll in the longitudinal portion (ESM+ N=621, 55.2%; ESM− N=503, 44.8%). Four items best discriminated ESM+ from ESM−. These were not the most commonly endorsed but were indicative of behavioral extremes.

Conclusions

Data suggest ESM+ is not rare in 6 to 12 year olds. ESM+ children show behavioral extremes including rapid mood shifts compared to ESM− children.

Keywords: Bipolar Disorder, Mania, Child, Adolescent

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a serious psychiatric disorder in youth. Lewinsohn, Klein, & Seeley (1995)1 noted the lifetime prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorders in older adolescents is ~1% with an additional 5.7% reporting having experienced subsyndromal symptoms of mania (“core positive subjects”). Epidemiological studies indicate that up to 60% of adults with bipolar disorder report their first symptoms while young (31% below age 14, 28% ages 15–19).2–5 Such findings lend support to the possibility of a high prevalence rate of bipolar disorder in youth.5,6

Although identified over a century ago7 and carefully described in 1960,8 bipolar disorder is controversial with respect to phenomenology, course, and treatment response prior to puberty.9 This controversy is fueled by several issues. First, the presentation of bipolar disorder may be different in youth. In adults, it typically presents with distinct mood states and inter-episode recovery. However, in youth, the illness has been described as: (1) brief mood episodes of rapid cycling and/or mixed states and infrequent inter-episode recovery; and (2) chronically irritable and dysphoric mood.9–12 Second, bipolar disorder symptoms (hyperactivity, impulsivity, irritability, and aggressive behavior) overlap with other psychiatric conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),9, 12–14 non-bipolar depression, and conduct disorder.15–18 Third, it is often comorbid with other psychiatric disorders such as ADHD.9, 12–14 Finally, there have been few epidemiologic studies and no longitudinal studies of youth selected for only elevated symptoms of mania (ESM), the phenomenological hallmark of bipolar disorder.1,19 These issues make bipolar disorder in youth difficult to diagnose and have prompted the call for longitudinal studies to disentangle the diagnostic issues.20

A longitudinal study of children with ESM who are putatively at greater risk for developing bipolar disorder is also justified by the developmental challenges of recognizing mania; the lack of knowledge about the positive predictive value of ESM; the increase in the rate of diagnosis of bipolar disorder in youth;21–25 and the growing evidence that many youth suffer from symptoms including mania associated with bipolar disorder for years prior to diagnosis and treatment.9, 11–12, 26–27 It is especially important to examine children with ESM since many of these children do not meet strict DSM criteria for either bipolar disorder-Type 1 (BP1) or bipolar disorder-Type 2 (BP2)27–30 yet suffer from considerable psychopathology and dysfunction.31 Further, little is known about the phenomenology or diagnostic course of children with ESM, and very little is known about their key prognostic features.29

Given the issues surrounding bipolar disorder in youth, the NIMH-supported Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) study was designed to: (1) document the rate of ESM using a valid and reliable measure in children 6–12 years attending outpatient mental health clinics; (2) describe the longitudinal course and diagnostic evolution of ESM from childhood to adolescence by following this cohort of children over time; and (3) identify childhood risk factors that predict poor functional outcomes in adolescence among children who present with ESM at study entry. This article describes the study design for LAMS and the prevalence and demographic correlates of ESM. The characteristics of the longitudinal cohort, including exclusions, diagnoses and treatment will be described elsewhere.

Method

Design

We constructed a two-phase study design to investigate the course of ESM in children. Two-phase designs are economical when the diagnosis of the condition of interest is complex or costly: a large population is assessed with a screening instrument and then some portion of that population is chosen for a more extensive diagnostic assessment.32–33 A prospective design allows the evaluation of ESM as a marker for developing bipolar disorder, determining whether certain risk factors (e.g., early trauma) are related to bipolar disorder, and examining the course and diagnostic evolution of children with ESM.34–36 We screened children visiting outpatient mental health clinics because of: (1) the rarity of manic symptoms in the general population of children; (2) our focus on diagnostic course rather than prevalence; and (3) the cost of screening in the community, particularly for only one symptom complex.37

Sample The source population consisted of all children between 6 and 12.92 years visiting 10 child outpatient mental health clinics (2 in Cleveland, 2 in Cincinnati, 5 in Columbus and 1 in Pittsburgh) associated with universities (Case Western Reserve University, University of Cincinnati, Ohio State University and University of Pittsburgh,) in the LAMS study. The lower bound of the age range was chosen because many child assessment measures have not been validated for children less than 6 years. Exclusion criteria included a prior visit to the participating outpatient clinics within the preceding 12 months, not being accompanied by a parent or legal guardian and having a parent who did not understand or speak English. Adults accompanying eligible children were approached and voluntarily provided written informed consent for participation in the screening portion of the study. The LAMS study was approved by the IRBs at each of the participating universities.

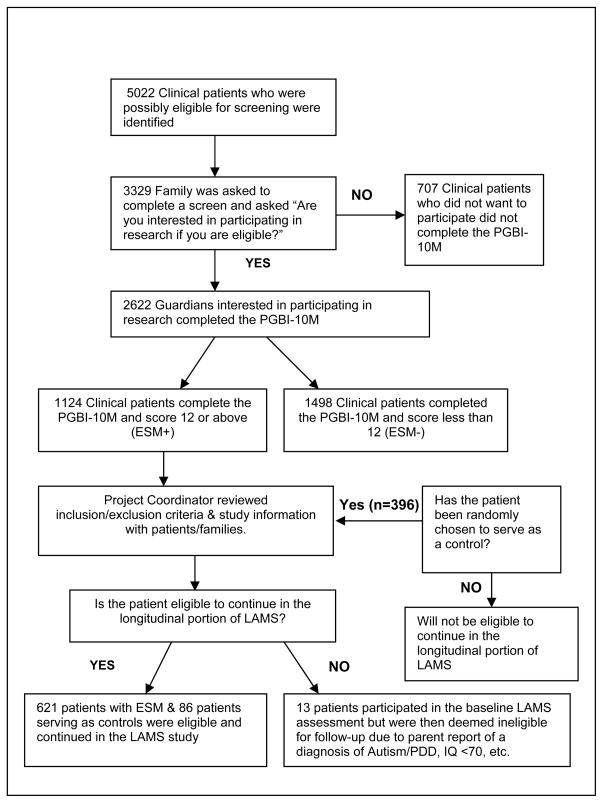

Participating adults of eligible children completed the Parent General Behavior Inventory-10 Item Mania Scale (PGBI-10M)38–39 and a few sociodemographic questions. All children with a PGBI-10M score ≥ 12(i.e., ESM+) were invited to enroll into the longitudinal phase of the study. Every 3–4 weeks at each study site, one child with a PGBI-10M score of ≤ 11 (i.e. ESM−) was selected for every 10 consecutive ESM+ children enrolled. Clinics serving a lower volume of children with ESM+ enrolled children in a 1:5 negative/positive ratio. Negative screens were chosen within 3–4 weeks of their visit because our pilot experience demonstrated more participant refusal beyond this time frame. Using minimization methods, the negative screen selected was matched by age (± 2 years), sex, race/ethnicity and insurance status of the “modal” positive child in the time segment. If more than one negative screen matched, the negative control was randomly selected and if a selected negative control refused he or she was replaced. Considered to be the only equivalent alternative to randomization, minimization ensures balance between study groups for several patient factors.40–41 This block size and selection method was chosen to ensure approximate balance between ESM+ and ESM− for any potential time trend changes in demographic characteristics of the “modal” ESM+ child (Figure 1). We invited to enroll in the longitudinal phase of the study parents who were informed that participation would entail ≥ 2 hour interviews twice yearly for up to 5 years.

Figure 1.

Patient Enrollment Strategy at each of the 4 Sites

Measures

Screening instrument

A two-phase design requires that a psychometrically sound screening instrument be available to differentiate individuals with and without the phenomenon of interest. Prepubertal children can be screened for mania and, as noted by Youngstrom et al.,38 the PGBI-10M performs better than other mania measures for this purpose. The PGBI-10M is a 10-item empirically-derived adaptation of the GBI.42–43 Parents rate the hypomanic, manic and biphasic mood symptoms of their children aged 5–17. Each item is scored from 0 (“Never or hardly ever”) to 3 (“very often or almost constantly”). Scores range from 0 to 30 with higher scores indicative of greater symptoms. The short form was developed by selecting items that maximally discriminated bipolar disorder from other diagnoses.39 The short form is highly reliable (α = .92) and maintains the excellent content coverage of the GBI (correlates .95 with the full length version). The PGBI-10M discriminates patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder from all others, with an area under the curve of .86.39 When scores of ≥ 12 were used as the cutoff in the scale development analyses, a specificity of 88% and a sensitivity of 64% was achieved at an outpatient clinic with a sample enriched with mood disorders.39 The diagnostic likelihood ratio44 that a child with a score of 12 or higher on the PGBI-10M had a bipolar diagnosis was 5.5.

Demographic form

Demographic characteristics reported by parents at screening included child age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance.

Analyses

Data were double-entered using SPSS Data Builder/Entry v.3. Data discrepancies were corrected and audits were conducted until all entry errors were corrected in the two entry files. Data were then exported to SPSS v.16 to examine out-of-range values, logical exclusions and inconsistencies indicative of response bias.

Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.2.45 Unweighted means, standard deviations, counts, and percentages were calculated for descriptive statistics. Variables were examined for their skewness and kurtosis. Between-group differences were assessed via the Rao-Scott Chi-Square test for binary variables and t-tests for continuous variables. The standardized effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d.46 All hypothesis tests were considered statistically significant if the p value was < 0.05.

Sample size and power analyses

The study was designed to provide adequate statistical power for longitudinal follow-up of cases to estimate rates of diagnostic change. In order to generate a large enough sample for the longitudinal aims, a much larger sample was screened. Based on the obtained sample size, with alpha set at .05, the study had 80% power to detect very small effect sizes, Cohen’s d values of .11 or larger for t-tests and Cohen’s w values of .065 or larger for chi-squared tests.47

Results

A total of 3329 children and families visited the study outpatient clinics during sample accrual (11/14/2005–11/28/2008). Of these, 79% (n=2622) were eligible and agreed to participate.. Two-thirds of the sample were male (66%, n=1730) and White (67%, n=1743), with a mean age of 9.4 years (SD=2.0, range 6.0–12.9). Forty-one percent (n=1074) of the visits were paid for by Medicaid and 53% (n=1395) by private insurance (Table 1). IRB regulations allowed limited information (child age and insurance status) to be collected on non-participants. Non-participating children were slightly younger (M=9.1 years, SD=2.0) in comparison to participating children (M=9.4 years, SD=2.0; t=4.42, df=3327, p<0.001) but payment for visits by Medicaid was similar (41.4% versus 41.0%, respectively; X2=0.05, df=1, p=0.82.) These results were consistent across sites with one exception, participating children in Pittsburgh were more likely to have visits paid for by Medicaid compared to non-participating children (54.3% versus 34.6%, respectively; X2=27.29, df=1, p<.0001).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Population According to Screening Status.

| Characteristic | Total (n=2622) |

Screen Positives (n=1124) |

Screen Negatives (n=1498) |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Age Category: | |||||||

| 6–8 years | 1160 | 44.2 | 547 | 48.7 | 613 | 40.9 | <.001 |

| 9–10 years | 758 | 28.9 | 299 | 26.6 | 459 | 30.6 | |

| 11–12 years | 704 | 26.8 | 278 | 24.7 | 426 | 28.4 | |

| Mean Age: | 9.4 | SD= 2.0 | 9.3 | SD= 2.0 | 9.6 | SD= 1.9 | |

| Sex: Male | 1730 | 66.0 | 755 | 67.2 | 975 | 65.1 | |

| Female | 891 | 34.0 | 369 | 32.8 | 522 | 34.8 | 0.28 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 1743 | 66.5 | 728 | 64.8 | 1015 | 67.8 | |

| Asian | 12 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.6 | 0.13 |

| African-American | 693 | 26.4 | 312 | 27.8 | 381 | 25.4 | |

| American Indian | 10 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.5 | |

| Multi-racial | 154 | 5.9 | 76 | 6.8 | 78 | 5.2 | |

| Other/Unknown | 10 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.5 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Latino | 83 | 3.2 | 47 | 4.2 | 38 | 2.5 | 0.04 |

| Non-Latino | 2526 | 96.3 | 1074 | 95.6 | 1450 | 96.8 | |

| Unknown | 13 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.3 | 10 | 0.7 | |

| Insurance Status: | |||||||

| Public | 1074 | 41.0 | 544 | 48.4 | 530 | 35.4 | <.001 |

| Private | 1395 | 53.2 | 507 | 45.1 | 888 | 59.3 | |

| Public and Private | 90 | 3.4 | 52 | 4.6 | 38 | 2.5 | |

| Self-pay | 23 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.0 | 12 | 0.8 | |

| Unknown | 40 | 1.5 | 10 | 0.9 | 30 | 2.0 | |

| Mean PGBI-10M score | 10.6 | SD=8.0 | 18.6 | SD=4.7 | 4.7 | SD=3.5 | <.001 |

Adults completed the PGBI-10M on the 2622 participating children; 43% had PGBI-10M scores of 12 or higher (i.e., a positive screen) When compared to negatively screened children, children with positive screens were more likely to be Latino (4.0% versus 2.5%, respectively; X2=4.43, df=1, p=0.04, d=0.09), younger (M=9.3 years, SD=2.0 versus M=9.6 years, SD=1.9: t=3.8, df=2620, p<.001, d=0.15) and supported by Medicaid (48.4% versus 35.4%, respectively, X2=45.00, df=1, p=<0.001, d=0.28). There were no significant differences between screen positives and screen negatives in terms of sex or race. Similarities and differences were largely consistent across sites with a few exceptions. Whites were less likely to be screen positives at the Pittsburgh, PA and Cleveland, OH sites and males were more likely to be screen positives in the Columbus, OH sites (data not shown).

Positive Screens

Children with positive screens whose families did (55.2%, n= 621) and did not agree (44.8%, n=503) to participate in phase-two of the study were examined. As shown in Table 2, no significant demographic differences emerged between groups in terms of child age, sex, race/ethnicity or insurance status. These findings were consistent across sites with one exception. In Pittsburgh, Whites were more likely to refuse participation in phase-two. These comparisons were not done for the screen negatives because they were sampled with replacements if they did not agree to participate in the longitudinal phase of the study.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Screen Positive Participants by Enrollment into the Longitudinal Study.

| Characteristic | Screen Positives |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes to Enrollment |

No to Enrollment |

||||

| N=621 | % | N=503 | % | P | |

| Age Category: | |||||

| 6–8 years | 301 | 48.5 | 246 | 48.9 | 0.68 |

| 9–10 years | 171 | 27.5 | 128 | 25.4 | |

| 11–12 years | 149 | 24.0 | 129 | 25.6 | |

| Sex: Male | 413 | 66.5 | 342 | 68.0 | 0.61 |

| Female | 208 | 33.5 | 161 | 32.0 | |

| Race: | |||||

| White | 395 | 63.6 | 333 | 66.2 | 0.17 |

| Asian | 2 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| African-American | 171 | 27.5 | 141 | 28.0 | |

| American Indian | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Multi-racial | 52 | 8.4 | 24 | 4.8 | |

| Other/Unknown | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Ethnicity: | |||||

| Latino | 26 | 4.2 | 19 | 3.8 | 0.76 |

| Non-Latino | 595 | 95.8 | 481 | 95.6 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Insurance Status: | |||||

| Public | 298 | 48.0 | 246 | 48.9 | 0.21 |

| Private | 289 | 46.5 | 218 | 43.3 | |

| Public and Private Insurance | 23 | 3.7 | 29 | 5.8 | |

| Self-pay | 8 | 1.3 | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.5 | 7 | 1.4 | |

| Mean PGBI-10M score | 18.4 | SD=4.7 | 18.8 | SD=4.8 | 0.22 |

Positive versus Negative Screens

Finally, we examined symptoms endorsed on the PGBI-10M for those screening positive compared to those screening negative (Table 3). As would be expected, all 10 items on the PGBI-10M were more frequently endorsed by those who screened positive. Among the positives, 4 items were endorsed most frequently: mood/energy shifted rapidly from happy to sad or high to low; days unusually happy & intensely energetic, yet also physically restless; shifting activities; and feelings/energy are generally up or down, but rarely in the middle. However, the items with the largest effect sizes, that is those that best discriminated between the positives and negatives, were items 1, 2, 6, and 9. Appendix A contains the full distribution of responses for ESM+ and ESM− subjects.

Table 3.

Symptoms endorsed on the Parent General Behavior Inventory-10 Item Mania Scale (PGBI-10M)

| Symptom | Screen Positives | Screen Negatives | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | p- value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| 1. Days of more depressed, irritable or extremely high, elevated, overflowing with energy | 658 | 58.5 | 52 | 3.5 | 2.24 | <.001 |

| 2. Unusually happy & intensely energetic, but everything got on nerves and made unhappy | 836 | 74.4 | 136 | 9.1 | 2.15 | <.001 |

| 3. Mood/energy shifted rapidly from happy to sad or high to low | 898 | 79.9 | 273 | 18.2 | 1.82 | <.001 |

| 4. Feelings/energy are generally up or down, but rarely in the middle | 850 | 75.6 | 191 | 12.8 | 1.92 | <.001 |

| 5. Days unusually happy & intensely energetic, yet also physically restless, shifting activities | 863 | 76.8 | 270 | 18.0 | 1.71 | <.001 |

| 6. Days of more extreme happiness or energy yet also anxious or tense | 627 | 55.8 | 56 | 3.7 | 2.23 | <.001 |

| 7. Days of more when others told you that child seemed unusually happy or high—clearly different self | 433 | 38.5 | 27 | 1.8 | 1.92 | <.001 |

| 8. Times thoughts/ideas came so fast couldn’t get these all out or others complained they could not keep up | 635 | 56.5 | 156 | 10.4 | 1.47 | <.001 |

| 9. Days of more unusually happy & energetic yet also struggled with rage or urge to smash/destroy | 745 | 66.3 | 89 | 5.9 | 2.27 | <.001 |

| 10. Days or more of extreme happiness & energy; took over an hour to get to sleep at night | 722 | 64.2 | 140 | 9.3 | 1.90 | <.001 |

Discussion

Data from these 6–12 year old first-time utilizers of general outpatient mental health clinics participating in this study suggest that symptoms of mania are common and that their prevalence may differ by demographic characteristics. Of the 2622 families who agreed to complete the PGBI-10M, 1124 or 42.9% scored their children as positive for symptoms of mania. Although a DSM-III-R diagnosis of mania has been reported in about 16% of outpatient users 12 years of age or younger,12 these data suggest that manic symptoms (as opposed to a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder) may be even more common in young outpatient utilizers. Participating children who scored positive for symptoms of mania display very different behavior than children who scored negative, as noted in a number of previous studies examining symptoms in bipolar youth compared to youth with other diagnoses.11, 33, 48

The children who scored positive for symptoms of mania showed no sex difference but were more likely to be younger, Latino, and publicly insured. The lack of any sex difference is consistent with prior reports of similar rates of bipolar diagnoses in males and females, and the findings also correspond with prior work indicating that higher levels of mania are found at younger ages.49 There is documentation that 10–20% of adults with bipolar disorder report onset before the age of 10.5, 50 However, whether the relationship of age to manic symptoms is due to the relationship of these symptoms to other common psychiatric problems such as ADHD, non-pathological age-related differences in behavior or age trends for decreasing levels of mania as reported by Cicero et al, 2009 51 cannot be determined by these data but, rather, by tracking subjects’ diagnostic evolution over time. Although the relationships of ethnicity and poverty (approximated by public insurance) have not been previously reported, the more general relationship of socioeconomic status and psychopathology in children has been documented.52–54 Given that the vast majority of investigations of diagnostic efficiency come from European-American middle and upper class samples, and that few Latinos participated in a study examining the performance of the screening instrument in subpopulations,39 this finding, although a small difference, needs to be replicated and explored.55 Unfortunately, as previously identified,50, 56–57 while very good data are available from regional epidemiological studies, data on prevalence and correlates of psychopathology from a national sample are scarce. However, the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) will provide critical data on the correlates of psychopathology for 13–17 year olds.56, 58 It will be informative to compare these ethnicity and socioeconomic findings to the NCS-A when they become available.

Examining the symptoms endorsed, we find that every symptom was endorsed more frequently in those scoring positive, but four symptoms contributed most strongly to the differences: (1) days of more depressed, irritable or extremely high, elevated or overflowing with energy mood; (2) being unusually happy and intensely energetic but irritable; (3) days of extreme happiness or energy but also anxious or tense and frequently shifting activities; and, (4) days or more of unusual happiness and energy coupled with rage and urge to smash or destroy things. Taken together, these symptoms describe children with considerable extremes in behavior, further, as pointed out by Youngstrom et al.55 in an extensive review of the evidence on the phenomenology of bipolar disorder in youth, these symptoms are highly specific to the disorder although, as reported by Shankman et al., 2009 59 the diagnostic evolution may not be homotypic. That every symptom was endorsed more frequently in those scoring positive is not surprising given that Youngstrom et al.39 selected items from the PGBI–10M that best discriminated between bipolar and non-bipolar cases.

Limitations

The data were generated from eligible children visiting general mental health outpatient clinics. Consequently, although representative of the 6–12 year old utilizers, the data may not be representative of all outpatient utilizers nor are they representative of children in the community. Although the screening portion of the study achieved a very good response rate (79%), only 55% of families with ESM+ children agreed to participate in the longitudinal portion of the study usually because of the time commitment demanded by the twice yearly ≥ 2 hour assessments. While there are no differences on the demographic variables available from the screening data for those who did and did not agree to enroll in phase-two, with just over one half of those eligible agreeing to participate in the follow-up, there may be differences between participating and non-participating families. Finally, these data were all self reported. There is no gold standard for indentifying mania and the PGBI-10M, although psychometrically sound and performing better than other mania measures, contains questions with multiple items imbedded within each item.38 Consequently, even though the exceptionally high internal consistency reliability argues against the item content being too heterogeneous we do not know precisely to what portion of a question parents are responding.

Conclusions

This cohort of 6 to 12 year old first time utilizers of participating outpatient mental health clinics enriched for symptoms of mania—the hallmark symptom of bipolar disorder—will provide the data necessary to determine the positive predictive power of early symptoms of mania for the development of bipolar disorder and identify risk factors associated with poor functional outcomes. Given the functional impairment and suffering caused by bipolar disorder in children, accurate diagnosis and treatment are critical. Data generated by this cohort of children and their families have the potential to inform both these important areas.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH073967). We thank them for their support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of NIMH. Dr. Findling receives or has received research support, acted as a consultant and/or served on a speaker’s bureau for Abbott, Addrenex, AstraZeneca, Biovail, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, KemPharm Lilly, Lundbeck, Neuropharm, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracore, Shire, Solvay, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Validus, and Wyeth. Dr. Arnold receives or has received research support, acted as a consultant and/or served on a speaker’s bureau for Abbott, Celgene, Lilly, McNeil, Novartis, Neuropharm, Organon, Shire, Sigma Tau, and Targacept. Dr. Birmaher receives or has received research support, acted as a consultant and/or served on a speaker’s bureau for Forest Laboratories, Inc. and Schering Plough. Dr. Frazier has acted as a consultant to Shire Development Inc. Drs. Fristad, Horwitz, Pagano and Youngstrom and the other authors have no financial interests to disclose.

Abbreviations

- ESM

elevated symptoms of mania

- LAMS

Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms Study

- PGBI-10M

Parent General Behavior Inventory-10 Item Mania Scale

- ESM+

screen positive

- ESM−

screen negative.

References

- 1.Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity and course. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:454–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Huang B. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:1205–1215. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RM, Petukhova M, Kessler RC. Lifetime and 12-Month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RMA. The National Depressive and Manic-depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1994;31:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leverich GS, Post RM, Keck PE, Jr, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Kupka RW, Nolen WA, Suppes T, McElroy SL, Grunze H, Denicoff K, Moravec MK, Luckenbaugh D. The poor prognosis of childhood onset bipolar disorder. Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;150:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greves FH. Acute mania in a child of five years: recovery & remarks. Lancet. 1884;ii:824–826. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anthony J, Scott P. Manic depressive psychosis in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1960;1:52–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Findling RL, Gracious BL, McNamara NK, Youngstrom EA, Demeter CA, Branicky LA, Calabrese JR. Rapid, continuous cycling and psychiatric co-morbidity in pediatric bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2001;3:202–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geller B, Sun K, Zimerman B, Luby J, Frazier J, Williams M. Complex and rapid cycling in bipolar children and adolescents: a preliminary study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1995;34:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00023-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geller B, Luby J. Child and adolescent bipolar disorder: a review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1168–1176. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kiely K, Ablon JS, Faraone SV, Mundy E, Mennin D. Mania-like symptoms suggestive of childhood-onset bipolar disorder in clinically referred children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:867–876. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199507000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, Soutullo CA. Diagnostic characteristics of 93 cases of prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar phenotype by gender, puberty and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2000;10:157–164. doi: 10.1089/10445460050167269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kowatch RA, Youngstrom EA, Danielyan A, Findling RL. Review and meta-analysis of the phenomenology and clinical characteristics of mania in children and adolescents. Bipolar Disorders. 2005;7:483–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowring MA, Kovacs M. Difficulties in diagnosing manic disorders among children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:611–614. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson GA. Mania and ADHD: comorbidity or confusion. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1998;51:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geller B, Williams M, Zimerman B, Frazier J, Beringer L, Warner KL. Prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar differentiate from ADHD by manic symptoms, grandiose delusions, ultra-rapid, ultradian cycling. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1998;51:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim EY, Miklowitz DJ. Childhood mania, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: a critical review of diagnostic dilemmas. Bipolar Disorders. 2002;4:215–225. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson GA, Kashani JH. Manic symptoms in a non-referred adolescent population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1988;15:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein RG, Pine DS, Klein DF. Resolved: mania is mistaken for ADHD in prepubertal children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:193–196. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199810000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naylor MW, Anderson JR, Kruesi MJ, Stoewe M. Pharmacoepidemiology of bipolar disorder in abused and neglected state wards. San Francisco, CA. Presented at the 49th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; San Francisco, CA. October 22–27, 2002.2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harpaz-Rotem I, Leslie DL, Martin A, Rosenheck RA. Changes in child and adolescent inpatient psychiatric admission diagnoses between 1995 and 2000. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005;40:642–647. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0923-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blader JC, Carlson G. Increased rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses among child, adolescent and adult U.S. psychiatric inpatients, 1996–2004. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;26:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, Moreno C, Laje G. National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:679–685. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreno C, Laje G, Blanco C, Jiang H, Schmidt AB, Olfson M. National trends in the outpatient diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in youth. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1032–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thuppal M, Carlson GA, Sprafkin J, Gadow KD. Correspondence between adolescent report, parent report and teacher report of manic symptoms. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmaology. 2002;12:27–35. doi: 10.1089/10445460252943542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson GA, Youngstrom EA. Clinical implications of pervasive manic symptoms in children. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;53:1050–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nottelmann E, Biderman J, Birmaher B, Carlson GA, Chang KD, Fenton WS, Geller B, Hoagwood KE, Hyman SE, Kendler KS, Koretz DS, Kowatch RA, Kupfer DS, Leibenluft E, Nakamura RK, Stover E, Vitiello B, Weiblinger G, Weller E. National Institute of Mental Health research roundtable on prepubertal bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:871–878. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazell PL, Carr V, Lewin TJ, Sly K. Manic symptoms in young males with ADHD predict functioning but not diagnosis after 6 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:552–560. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046830.95464.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, McNamara NK, Stansbrey RJ, Demeter CA, Bedoya D, Kahana SY, Calabrese JR. Early symptoms of mania and the role of parental risk. Bipolar Disorders. 2005;7:623–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlson GA, Loney J, Salisbury H, Volpe R. Young referred boys with DICA-P manic symptoms vs. two comparison groups. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1998;51:113–121. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrout PE, Newman SC. Design of two-phase prevalence surveys of rare disorders. Biometrics. 1989;45:549–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A. 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:972–986. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000172552.41596.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Post RM, Leverich GS. The role of psychosocial stress on the onset and progression of bipolar disorder and its comorbidities: the need for earlier and alternative modes of therapeutic intervention. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:1181–1211. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kessler RC. Psychiatric epidemiology: selected recent advances and future directions. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:464–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jablensky A. Research methods in psychiatric epidemiology: an overview. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;36:297–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelsey JL, Thompson WD, Evans AS. Methods in observational epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Youngstrom E, Meyers O, Demeter C, Youngstrom J, Morello L, Piiparinen R, Feeny N, Calabrese JR, Findling RL. Comparing diagnostic checklists for pediatric bipolar disorder in academic and community mental health settings. Bipolar Disorders. 2005;7:507–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Youngstrom EA, Frazier TW, Demeter C, Findling RL, Calabrese JR. Developing a 10-Item mania scale from the Parent General Behavior Inventory for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008a;69:831–839. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott NW, McPhereson GC, Ramsay CR, Campbell MK. The method of minimization for allocation to clinical trials: a review. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2002;23:662–674. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT Statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2001:1:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Danielson CK, Calabrese JR. Discriminative validity of parent report of hypomanic and depressive symptoms on the General Behavior Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:267–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Calabrese JR, Gracious BL, Demeter C, Bedoya DD, Price M. Comparing the diagnostic accuracy of six potential screening instruments for bipolar disorder in youths aged 5 to 17 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:847–858. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000125091.35109.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Straus SE, Richardson WS, Glasziou P, Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: How to Practice and teach EBM. 3. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2005 . [Google Scholar]

- 45.SAS Institute, SAS 9.2. Carey, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carlson GA, Meyer SE. Bipolar disorder in youth. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2000;2:90–94. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duax JM, Youngstrom EA, Calabrese JR, Findling RL. Sex differences in pediatric bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68:1565–1573. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pavuluri MN, Birmaher B, Naylor MW. Pediatric bipolar disorder: a review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 44:846–871. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000170554.23422.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cicero DC, Epler AJ, Sher KJ. Are there developmentally limited forms of bipolar disorder? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:431–447. doi: 10.1037/a0015919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: a natural experiment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:2023–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McLeod JD, Shanahan MJ. Trajectories of poverty and children’s mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:207–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bor W, Najman JM, Andersen MJ, O’Callaghan M, Williams GM, Behrens BC. The relationship between low family income and psychological disturbance in young children: an Australian longitudinal study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;31:664–675. doi: 10.3109/00048679709062679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Youngstrom EA, Birmaher B, Findling RL. Pediatric bipolar disorder: validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disorders. 2008b;10:194–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merikangas K, Avenevoli S, Costello J, Koretz D, Kessler RC. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): I. Background and measures. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:367–369. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819996f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merikangas KR, Low NC. The epidemiology of mood disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2004;6:411–421. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Heeringa S, Merikangas KR, Pennell BE, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): II. Overview and design. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:380–385. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181999705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shankman SA, Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Small JW, Seeley JR, Altman SE. Subthreshold conditions as precursors for full syndrome disorders: a 15-year longitudinal study of multiple diagnostic classes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1485–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.