Abstract

Studies have shown that the superoxide mechanism is involved in angiotensin II (ANG II) signaling in the central nervous system. We hypothesized that ANG II activates sympathetic outflow by stimulation of superoxide anion in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats. In α-chloralose- and urethane-anesthetized rats, microinjection of ANG II into the PVN (50, 100, and 200 pmol) produced dose-dependent increases in renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA), arterial pressure (AP), and heart rate (HR) in control and STZ-induced diabetic rats. There was a potentiation of the increase in RSNA (35.0 ± 5.0 vs. 23.0 ± 4.3%, P < 0.05), AP, and HR due to ANG II type I (AT1) receptor activation in diabetic rats compared with control rats. Blocking endogenous AT1 receptors within the PVN with AT1 receptor antagonist losartan produced significantly greater decreases in RSNA, AP, and HR in diabetic rats compared with control rats. Concomitantly, there were significant increases in mRNA and protein expression of AT1 receptor with increased superoxide levels and expression of NAD(P)H oxidase subunits p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox in the PVN of rats with diabetes. Pretreatment with losartan (10 mg·kg−1·day−1 in drinking water for 3 wk) significantly reduced protein expression of NAD(P)H oxidase subunits (p22phox and p47phox) in the PVN of diabetic rats. Pretreatment with adenoviral vector-mediated overexpression of human cytoplasmic superoxide dismutase (AdCuZnSOD) within the PVN attenuated the increased central responses to ANG II in diabetes (RSNA: 20.4 ± 0.7 vs. 27.7 ± 2.1%, n = 6, P < 0.05). These data support the concept that superoxide anion contributes to an enhanced ANG II-mediated signaling in the PVN involved with the exaggerated sympathoexcitation in diabetes.

Keywords: central nervous system, renin-angiotensin system, sympathetic nerve activity

various types of autonomic abnormalities in relation to the cardiovascular system have been observed in diabetic patients and various animal models of diabetes, including streptozotocin (STZ)-induced type 1 diabetes (4, 11). Autonomic dysfunction found in patients with diabetes causes abnormalities in the regulation of heart rate, as well as defects in central and peripheral vascular dynamics. Many studies have demonstrated the importance of renal sympathetic nerves in the development of cardiovascular complications (9, 10). Stimulation of renin release, renal vasoconstriction, and promotion of the renal tubular reabsorption of sodium are the likely mediating mechanisms. This increase in sympathetic outflow to the kidneys appears to be causally related to the development of cardiovascular complications in diabetes (29).

Our laboratory has carried out a series of experiments documenting the central mechanisms involved in sympathetic abnormalities contributing to the altered neurohumoral drive during STZ-induced diabetes (27, 40, 42). Evidence indicates that the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus is involved in the blunted renal sympathoinhibition in response to acute volume expansion in the STZ-induced diabetic rat. We also have revealed significant increases in the neural activity in the PVN of rats with STZ-induced diabetes (18). This suggests that the neurons in the PVN are activated, and this may contribute to the autonomic dysfunction during type 1 diabetes.

Angiotensin II (ANG II) acting via the ANG II type 1 (AT1) receptor has many effects on the cardiovascular and renal systems that lead to the progression of cardiovascular and kidney disease in diabetes. Clinical studies have shown that inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) prevents cardiovascular complications of diabetes (HOPE, LIFE, and RENAAL studies) (8, 17, 37). In the brain ANG II regulates sympathetic outflow, facilitates sympathetic neurotransmission, and modulates cardiovascular reflexes (3, 15). Functional studies have shown AT1 receptors are involved in the PVN-mediated autonomic outflow (7, 19). Recently, we reported that ANG II stimulation in the PVN induces an increase in renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) (21). AT1 receptors in the PVN also have been found to be involved in central mechanisms regulating cardiovascular function during hypertension and chronic heart failure (20, 41).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have important effects on central neural mechanisms in blood pressure regulation, volume homeostasis, and autonomic function (35, 43). ROS contribute to abnormal afferent and reflex function in STZ-induced diabetic animals (35). ANG II has been shown to be a potent stimulator of ROS (14, 32). Central AT1 receptors have been found to be involved in signal transduction pathways that rely on ROS (32, 36). Zimmerman et al. (44) have shown that the effects of central ANG II on blood pressure, heart rate, and drinking are abolished by pretreatment with adenoviral superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the brain. This result suggests that ROS play a key role in the central neuronal and functional effects of ANG II. The mechanism by which ANG II stimulates superoxide anion production appears to be related to activation of NAD(P)H oxidase (44).

We hypothesized that upregulation of central ANG II-superoxide signaling pathways within the PVN contribute to sympathoexcitation in STZ-induced diabetic rats. In this study, we determined whether central effects of ANG II, specifically within the PVN, are through the activation of NAD(P)H oxidase with the subsequent production of superoxide anion in diabetic rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Induction of Type 1 Diabetes

This study was approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of the National Institutes of Health and the American Physiological Society. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–220 g; Sasco) were maintained in vivarium with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Standard laboratory chow and tap water were available ad libitum. Rats were injected with STZ (65 mg/kg ip in 0.1 M citrate buffer; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to induce diabetes. Onset of diabetes was identified by polydipsia, polyuria, and blood glucose levels >250 mg/dl. Experiments were performed 6–7 wk after the injection of STZ or vehicle (0.1 M citrate buffer).

General Surgery for Recording of RSNA, Arterial Pressure, and Heart Rate

Rats were anesthetized with α-chloralose (70 mg/kg ip) and urethane (0.75 g/kg ip). The femoral vein was cannulated for administration of supplemental anesthesia and 0.9% saline. The femoral artery was cannulated for recording arterial pressure (AP) and heart rate (HR). The left renal nerve was isolated, and the electrical signal was recorded with PowerLab (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). The changes in integration and frequency of the nerve discharge are expressed as a percentage from basal value. Responses of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and HR are expressed as the difference between the basal value and the value after each dose of a drug.

Stereotaxic Placement of Microsyringe and Microinjection into the PVN

Rats were placed in a stereotaxic device. An incision was made on the midline of the scalp to expose bregma. With the use of a brain atlas (28), the coordinates of the right PVN with reference to bregma were calculated as being 1.3 mm posterior, 0.4 mm lateral, and 7.8 mm ventral to the dura. A needle (0.5-mm outer diameter, 0.1-mm inner diameter) that was connected to a microsyringe (0.5 μl) was lowered into the PVN. At the completion of the experiment, monastral blue dye (2% Chicago blue, 30 nl) was injected into the brain for histological verification.

Microinjection Experimental Protocol

Experiment 1.

RSNA, AP, and HR were measured in control (n = 9) and diabetic rats (n = 8). ANG II was injected into the PVN in three doses (50, 100, and 200 pmol in 50–200 nl). The doses were given consecutively at intervals of 20 min in a random order. Maximum changes in RSNA, MAP, and HR were determined. In another set of five control rats and five diabetic rats, the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan was injected (25, 50, 100 nmol in 25–100 nl) into the PVN. The responses in RSNA, AP, and HR over 30 min were recorded after each dose administration.

Experiment 2.

To substantiate the notion that any responses of RSNA, AP, and HR were within the PVN and not by a peripheral action, the responses of changes in RSNA, AP, and HR were recorded after intravenous injection of 500 pmol of ANG II in both control (n = 9) and diabetic rats (n = 8).

Experiment 3.

The responses of RSNA, AP, and HR to ANG II were collected in a group of rats (n = 5) in which the injection site was not in the area of the PVN. This group is termed the anatomical control group.

Brain Histology

At the end of the experiment, the brain was removed and fixed in 4% formaldehyde. Serial transverse sections (30 μm) were cut using a cryostat and stained using 1% neutral red. The presence of blue dye within the PVN was determined using a light microscope. Dye that was located in the PVN was considered to be a “hit” on the PVN.

Micropunch of PVN and Isolation of mRNA for Real-Time RT-PCR and Protein for Western Blot Measurements

In a separate group of rats, the brain was removed and frozen on dry ice. Six serial coronal sections (100 μm) were cut at the level of the PVN with a cryostat, and according to the Palkovits and Brownstein technique (25), the PVN was bilaterally punched with an 18-gauge needle. Six of the punches were placed in 500 μl of Tri reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH), followed by extraction of mRNA. The other six punches for each brain were placed in 100 μl of protein extraction buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) to extract the protein.

Real-Time RT-PCR Measurement of AT1 Receptor, NAD(P)H Oxidase Subunits, and CuZnSOD mRNA

Real-time RT-PCR measurements were made with the iCycler iQ multicolor real-time detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The reaction mixture consisted of SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad), 300 nM sense and antisense primers, and the cDNA template of interest. Relative expression of AT1 receptor, NAD(P)H oxidase subunits, and CuZnSOD mRNA was normalized to the expressed reference gene: ribosomal protein L19 (rpl19). The data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method (22).

Western Blot Measurement of AT1 Receptor and NAD(P)H Oxidase Subunit Protein

The protein samples were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE gel and subjected to electrophoresis. The fractionated proteins on the gel were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membrane was probed with primary antibody [rabbit anti-AT1, anti-p22phox, and anti-p47phox, goat anti-p67phox (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), or rabbit anti-β-tubulin (1:2,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology)] overnight and then probed with secondary antibody (peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or -goat IgG, 1:5,000; Pierce, Rockford, IL). An enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce) was applied to the membrane, followed by an exposure within a UVP system (UVP BioImaging, Upland, CA) for visualization. Kodak 1D software (Kodak, Rochester, NY) was used to quantify the signal. The expression of protein was calculated as the ratio of intensity of the AT1 receptor and NAD(P)H oxidase subunit bands, respectively, relative to the intensity of β-tubulin band.

Dihydroethidium Staining

To evaluate the superoxide production in the PVN, we incubated fresh frozen sections (30 μm) with 2 μM dihydroethidium (DHE; Molecular Probes) for 30 min in the dark at 37°C. Sections were evaluated under a fluorescent microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and digitally photographed. OpenLab 4.0.3 (Improvisation, Lexington, MA) was used to identify the total intensity of positive staining. Three alternate sections (1.8 ± 0.1 mm posterior to bregma) representing the PVN were analyzed, and then the mean data were calculated.

AT1 Receptor Antagonist Losartan Treatment in Drinking Water

Rats were injected with STZ or vehicle 3 wk before one-half of the rats in each group received the ANG II AT1 receptor antagonist losartan (10 mg·kg−1·day−1; Merck, Rahway, NJ) in drinking water for an additional 3 wk. Thus there were four groups of rats in this experiment (control, control + losartan, diabetic, and diabetic + losartan).

Adenoviral Transfection of SOD Gene Into the PVN

Five weeks after STZ injection, adenoviral vectors carrying the human cytoplasmic SOD (AdCuZnSOD) or bacterial β-galactosidase gene (AdβGal; as a control vector) were delivered into the PVN unilaterally by microinjection (1 × 108 pfu/ml, 100 nl). We have compared the time course of CuZnSOD expression levels at 3, 5, 7, 10, and 12 days after gene transfer. We did not see a significant difference in expression from day 3 to day 7. Also, previous use of this adenovirus indicated that central injection of this adenovirus results in robust transgene expression in the brain by 3 days and for up to 4 wk without inflammatory effects (45). Four groups of rats were used in this study (control + AdβGal, control + AdCuZnSOD, diabetic + AdβGal, and diabetic + AdCuZnSOD). Seven days after injection, the rats were used for functional experiments. The location of the microinjection and the transfection efficiency (SOD expression) were determined using immunofluorescent staining and real-time PCR.

Immunofluorescent Staining

Rats were perfused transcardially with heparinized saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was placed in 30% sucrose. Sections 30 μm in thickness were cut with a cryostat. The sections were incubated with 10% normal donkey serum for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibody against CuZnSOD (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. The sections were incubated with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 2 h. Distribution of CuZnSOD immunofluorescence within the PVN was viewed using a fluorescent microscope (Leica) and digitally photographed.

Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to a two-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls test for comparison between means. P values <0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

General Data

Table 1 summarizes the salient morphological characteristics of control and diabetic rats. The mean blood glucose level for the control group was significantly lower than the blood glucose level in the diabetic group (P < 0.05). Before the microinjection of ANG II into the PVN, basal RSNA in diabetic rats was significantly higher than that in control rats (P < 0.05). MAP was not significantly different between the control and the diabetic group. The control group had a significant higher baseline HR compared with the diabetic group (P < 0.05). After adenoviral transfection, there were no significant differences in the basal RSNA, MAP, or HR between AdβGal- and AdCuZnSOD-treated control and diabetic groups (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of control and diabetic rats in the microinjection experiments

| Control | Diabetic | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 8 |

| Body weight, g | 373 ± 21 | 232 ± 17* |

| Blood glucose, mg/dl | 103 ± 11 | 452 ± 23* |

| Basal blood pressure, mmHg | 94 ± 9 | 89 ± 9 |

| Basal heart rate, beats/min | 364 ± 29 | 331 ± 25* |

| Basal int. RSNA, μV·s | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.2* |

Values are mean±SE; n = no. of rats.

Int. RSNA, integrated renal sympathetic nerve activity.

P < 0.05 vs. control rats.

Table 2.

Characteristics of control and diabetic rats in the viral transfection experiment

| Control + AdβGal | Diabetic + AdβGal | Control + AdCuZnSOD | Diabetic + AdCuZnSOD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Body weight, g | 367 ± 20 | 241 ± 13* | 353 ± 18 | 238 ± 11* |

| Blood glucose, mg/dl | 105 ± 4 | 421 ± 36* | 103 ± 6 | 412 ± 26* |

| Basal blood pressure, mmHg | 93 ± 8 | 87 ± 3 | 92 ± 9 | 87 ± 2 |

| Basal heart rate, beats/min | 378 ± 31 | 324 ± 11* | 369 ± 28 | 319 ± 18* |

| Basal int.RSNA, μV·s | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.4* | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.3* |

Values are mean ± SE.

indicates P < 0.05 vs. control rats.

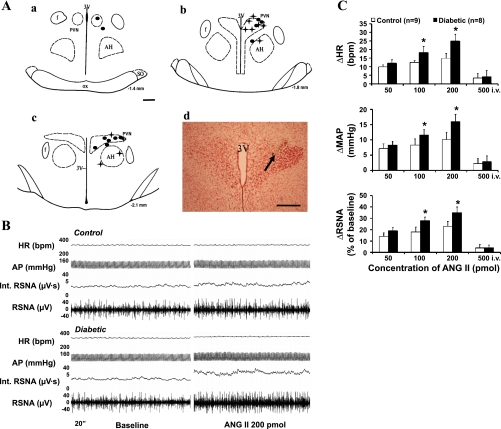

Figure 1A is a schematic illustrating the location of injection sites of ANG II into the PVN. Of 22 microinjections, 17 were located within the PVN and 5 were outside of the PVN and therefore analyzed separately as anatomic controls. Administration of ANG II into these sites (anatomic controls) did not produce increases in RSNA in response to ANG II injected into the PVN.

Fig. 1.

A, a–c: schematic representations of serial sections from the rostral (−1.4) to the caudal (−2.1) extent of the region of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). The distance (in mm) posterior to bregma is shown for each section. Each filled circle represents the site of termination of an injection that is considered to be within the PVN region in the control group; a plus symbol (+) represents the same in the diabetic group. d: Histological photo showing the injection site (arrow) in the PVN of one rat. AH, anterior hypothalamic nucleus; f, fornix; 3V, third ventricle; OX, optic tract; SO, supraoptic nucleus. Bars, 0.5 mm. B: segments of original recordings from an individual control rat (top) and diabetic rat (bottom) demonstrating the representative response to heart rate (HR), arterial pressure (AP), integrated renal sympathetic nerve activity (Int. RSNA), and RSNA to the microinjections of ANG II into the PVN. C: mean changes (Δ) in HR, mean arterial pressure (MAP), and RSNA after microinjections of ANG II into the PVN (50–200 pmol) and intravenous injection (500 pmol iv) in control and diabetic rats. *P < 0.05 vs. control group. bpm, Beats/min.

Increased Responses to Microinjection of ANG II Into the PVN

Experiment 1.

Administration of ANG II (50, 100, and 200 pmol in 50–200 nl) in the PVN elicited increases in RSNA, MAP, and HR in both groups. Microinjection of ANG II elicited increases in RSNA, MAP, and HR, reaching 23 ± 4%, 10 ± 2 mmHg, and 15 ± 3 beats/min, respectively, at the highest dose in control rats. The RSNA, MAP, and HR responses were significantly elevated in the diabetic rats compared with the control rats, reaching 35 ± 5%, 16 ± 2 mmHg, and 25 ± 4 beats/min, respectively, at the highest dose (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1C). An example of the responses in RSNA, AP, and HR to administration of ANG II (200 pmol) into the PVN in a control and diabetic rat is shown in Figure 1B.

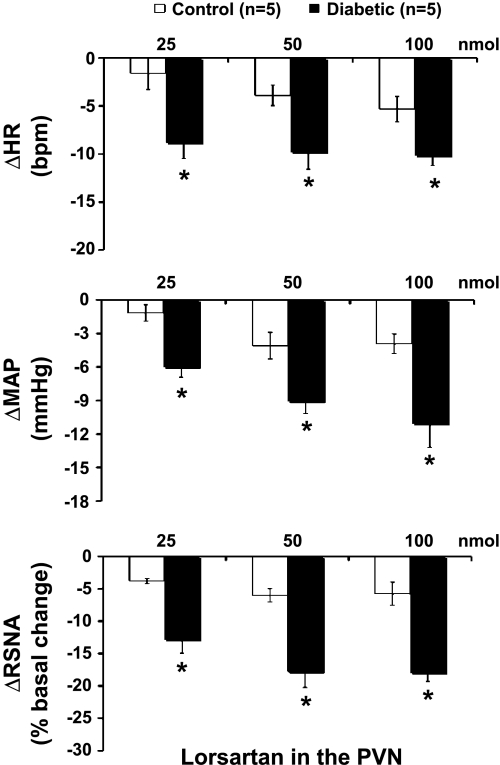

Microinjection of losartan into the PVN decreased RSNA, MAP, and HR in both control and diabetic rats, although just barely in the control rats. The responses of RSNA, MAP, and HR to losartan in diabetic rats were significantly greater than the responses of control rats (RSNA: −18 ± 1 vs. −6 ± 2%; MAP: −11 ± 2 vs. −4 ± 1 mmHg; HR: −10 ± 1 vs. −5 ± 1 beats/min at the highest dose, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean changes in RSNA, mean arterial pressure (MAP), and HR after microinjections of losartan (25–100 nmol) into the PVN in control and diabetic rats. *P < 0.05 vs. control group.

Experiment 2.

We also examined the possibility that the observed effects of ANG II were mediated by the peripheral effect. Intravenous administration of 500 pmol of ANG II (2.5 times highest dose) elicited no change in RSNA, MAP, or HR in both control and diabetic rats (Fig. 1C).

Experiment 3.

Similarly, microinjection of ANG II outside the PVN did not change RSNA, AP, or HR (data not shown).

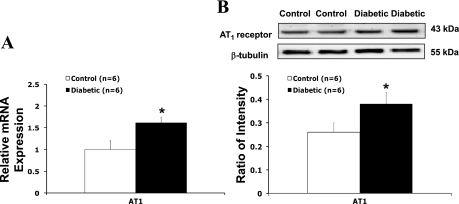

AT1 Receptor mRNA and Protein Expression in the PVN

Results from real-time RT-PCR experiments indicated that there was a significantly higher level of AT1 receptor mRNA in diabetic rats (Fig. 3A). Western blotting showed 43-kDa bands representing AT1 receptor in the PVN of control and diabetic rats. Diabetic rats had a significantly higher protein level of AT1 receptor compared with the control group (ratio of intensity: 0.39 ± 0.06 vs. 0.27 ± 0.03, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

A: gene expression of ANG II type I (AT1) receptors in the PVN tissue measured. Mean band densities of AT1 receptors were normalized to that of the reference gene, ribosomal protein L19 (rpl19), in control and diabetic rats. B: protein level of AT1 receptors in the PVN tissue. Top, example of visualized bands of AT1 receptors and β-tubulin; bottom, mean band densities of AT1 receptors normalized to β-tubulin. *P < 0.05 vs. control group.

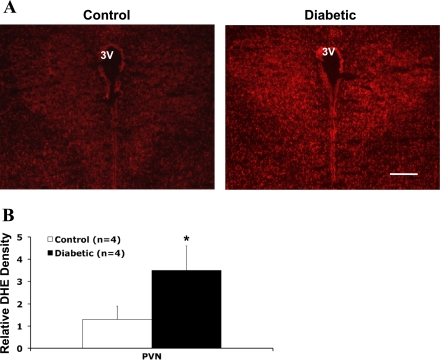

Superoxide Production in the PVN

To provide direct evidence that there was an increase in intracellular superoxide levels in the central nervous system of diabetic rats, we used DHE fluorescence staining to estimate superoxide levels in the PVN of control and diabetic rats (Fig. 4A). Quantitative analyses (Fig. 4B) showed that there was a significant increase relative to basal fluorescence observed in diabetic rats (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

A: immunofluorescence photomicrographs from sections of the PVN region stained for dihydroethidium (DHE; red). Bar, 0.5 mm. B: quantification of DHE intensity in the PVN. *P < 0.05 vs. control group.

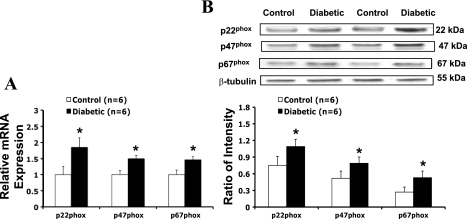

NAD(P)H Oxidase Subunit mRNA and Protein Expression in the PVN

As shown in Fig. 5, mRNA (A) and protein expression (B) for p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox were significantly increased in diabetic rats compared with control rats. In the PVN of diabetic rats, p22phox mRNA expression increased 84 ± 10% and protein level increased 45 ± 10% (n = 6, P < 0.05), p47phox mRNA expression increased 50 ± 8% and protein level increased 52 ± 8% (n = 6, P < 0.05), and p67phox mRNA expression increased 48 ± 8% and protein level increased 96 ± 9% (n = 6, P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

A: gene expression of p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox in the PVN tissue measured. Mean p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox mRNA expression were normalized to expression of rpl19. B: protein levels of p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox in the PVN tissue. Top, example of visualized bands of p22phox, p47phox, p67phox, and β-tubulin; bottom, mean band densities normalized to β-tubulin. *P < 0.05 vs. control group.

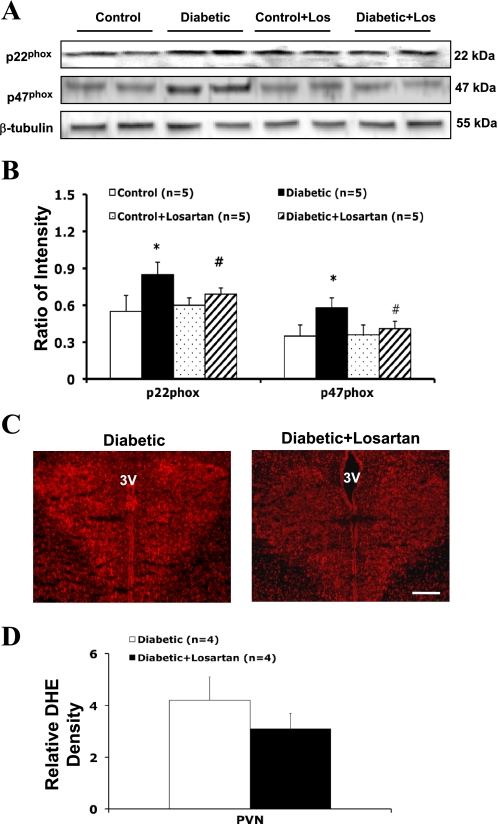

Effects of AT1 Receptor Antagonist Losartan on NAD(P)H Oxidase Subunit Protein Expression and Superoxide Levels in the PVN

Pretreatment with the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan (10 mg·kg−1·day−1 in drinking water for 3 wk) significantly reduced NAD(P)H oxidase subunit (p22phox and p47phox) protein expression in the PVN of diabetic rats (Fig. 6, A and B). In the PVN of diabetic + losartan-treated rats, p22phox protein level was reduced 24 ± 5% (n = 5, P < 0.05) and p47phox protein level was reduced 30 ± 5% (n = 5, P < 0.05) compared with diabetic nontreated rats. Losartan treatment had no significant effects on p67phox protein expression in the PVN. High-level DHE staining was observed in the PVN of a diabetic rat (Fig. 6C). Quantitative analyses (Fig. 5D) showed that there was no significant difference in relative basal fluorescence observed between diabetic rats and diabetic + losartan-treated rats.

Fig. 6.

A: example of visualized bands of p22phox, p47phox, and β-tubulin in the PVN in losartan treatment experiment. Los, losartan. B: mean band densities normalized to β-tubulin. *P < 0.05 vs. control group. #P < 0.05 vs. diabetic group. C: immunofluorescence photomicrographs from sections of the PVN region stained for DHE (red). Bar, 0.5 mm. D: quantification of DHE intensity in the PVN.

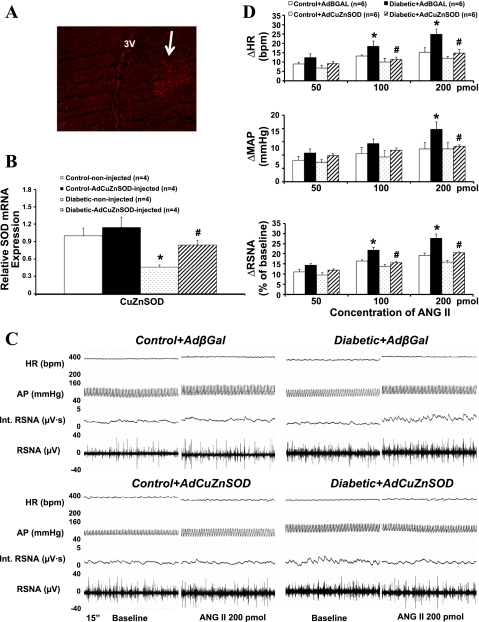

Adenovirus-Mediated Transgene Expression in the PVN

To verify adenovirus-mediated transgene expression in the PVN, we performed immunofluorescent analyses on brains of rats from the AdCuZnSOD treatment groups (n = 4). In AdCuZnSOD-injected rats, human CuZnSOD immunoreactivity was detected in the virus-injected side of the PVN in a diabetic rat (Fig. 7A). In addition, significantly higher levels of CuZnSOD mRNA levels were observed in the AdCuZnSOD-injected diabetic rats compared with the AdβGal-injected diabetic rats as shown using real-time PCR (n = 4, Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

A: immunofluorescence photomicrographs from sections of the PVN region stained for CuZn superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD; red) in a diabetic rat. Arrow points to the site infected with adenoviral vector carrying CuZnSOD (AdCuZnSOD). Bar, 0.5 mm. B: real-time PCR quantification of CuZnSOD in the PVN after AdCuZnSOD transfection. C: segments of original recordings from individual control + adenoviral vector carrying the bacterial β-galactosidase gene (AdβGal), diabetic + AdβGal, control + AdCuZnSOD, and diabetic + AdCuZnSOD transfected rats, demonstrating the representative responses to HR, AP, int. RSNA, and RSNA to the microinjections of ANG II into the PVN. D: mean changes in RSNA, MAP, and HR after microinjections of ANG II into the PVN in 4 groups of rats. *P < 0.05 vs. control group. #P < 0.05 vs. diabetic + AdβGal group.

Effects of AdCuZnSOD Transfection in the PVN on ANG II-Induced RSNA, AP, and HR Responses

Administration of ANG II (50, 100, and 200 pmol in 50–200 nl) in the PVN elicited increases in RSNA, MAP, and HR in all four groups (control + AdβGal, control + AdCuZnSOD, diabetic + AdβGal, and diabetic + AdCuZnSOD, Fig. 6D). The potentiated responses in diabetic rats were prevented by pretreatment with AdCuZnSOD within the PVN (RSNA: 20 ± 1 vs. 28 ± 2%, n = 6, P < 0.05). An example of the peak responses in RSNA, AP, and HR to ANG II in the four groups is shown in Fig. 7C.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that there were increased responses in RSNA, AP, and HR to ANG II within the PVN in diabetic rats. Furthermore, blocking the endogenous effects of ANG II by blocking AT1 receptors within the PVN produced a greater decreased in RSNA, AP, and HR in diabetic rats. Concomitantly, there was a significant increase in mRNA and protein expression of AT1 receptor and significant increases in superoxide levels and the NAD(P)H oxidase subunits p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox in the PVN of STZ-induced diabetes. Pretreatment with losartan significantly reduced p22phox and p47phox protein expression in the PVN of diabetic rats. The potentiated responses to ANG II were attenuated by pretreatment with AdCuZnSOD within the PVN of diabetic rats. These data show that the central ANG II-mediated signaling in the PVN contributes to the elevated sympathetic drive, and this signaling is mediated in part by an enhanced superoxide mechanism within the PVN of rats with diabetes.

In the STZ-induced diabetic rats, we did not see an increase in the baseline blood pressure. These results are consistent with other studies using the STZ-induced type 1 diabetic model (34). Although we measured baseline blood pressure in anesthetized animals, other studies in conscious animals have also shown the same results (2). Blood pressure is a consequence of a number of factors, including RSNA-mediated changes in renovasoconstriction. There may have been some differential changes in sympathetic outflow such that there may be vasodilation in other vascular beds. Such differential outflow has been demonstrated previously in other studies (26). The lack of an increase in blood pressure with a concomitant increase in RSNA in STZ-induced diabetic animals maybe be attributed to a number of possible contributing factors, including 1) decreased cardiac output due to a dysfunction in the myocardium, 2) differential sympathetic outflow, 3) hypovolemia due to osmotic diuresis, and 4) impairment of sympathetic innervation of heart and blood vessels (2).

In the present study, blocking the endogenous action of ANG II within the PVN via AT1 receptors by administration of losartan produced a greater sympathoinhibition in rats with diabetes compared with control rats. Furthermore, microinjections of ANG II into the PVN induced a greater increase in RSNA, AP, and HR in rats with diabetes. Consistent with these observations, we have shown that there is a concomitant increase in AT1 receptor, NAD(P)H oxidase subunits, and superoxide within the PVN of diabetic rats. These results support the concept that both central ANG II responses and superoxide generation are increased in the brains of diabetic rats. Thus the potentiated response to ANG II may contribute to the enhanced sympathoexcitation in diabetes.

Changes in excitatory synaptic function can occur by presynaptic mechanisms such as altered neurotransmitter release and/or postsynaptic mechanisms. We observed that AT1 receptors were upregulated in the PVN in diabetic rats, which is associated with an enhanced ANG II receptor function. This may be one of the central mechanisms underlying the elevated sympathoexcitation in diabetes. Therefore, we proposed that AT1 receptor antagonism with losartan might be beneficial in preventing the generation of superoxide, thereby reducing oxidant injury in diabetes. During losartan treatment, we found significant reduction of p22phox and p47phox protein expression in the PVN of diabetic rats. This indicates that ANG II-mediated sympathoexcitation signaling in the brain is related to activation of NAD(P)H oxidase. Administration of losartan tended to reduce the superoxide overproduction in diabetic rats but did not reach statistical significance. This may be due to the relative lower dose of losartan treatment in the present study, or, alternatively, other mechanisms may have contributed partially to the oxidant generation in diabetes. (5). This possibility remains to be examined further.

Consistent with these observations, angiotensin receptor blockers have been shown to protect against diabetes and diabetic complications, possibly with effects on central ANG II mechanisms within the hypothalamus. Several studies have shown a relationship between angiotensin receptor blockers and preservation of cardiovascular function as well as neural and cognitive function in diabetes (1, 13). Studies in both animals and humans found that angiotensin receptor blockers help to prevent cardiovascular complications common in diabetes. In the present study, we did not measure the circulating ANG II levels. In STZ diabetic rats, plasma ANG II levels are reported to be increased (46). Although ANG II does not cross the blood-brain barrier, circulating levels of ANG II may affect the central nervous system, including the PVN, through some of the circumventricular organs (CVOs), such as the subfornical organ and the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (23). The neurons in the CVOs have projections to the PVN. We think that through this potential pathway, the circulating ANG II could affect the local ANG II levels in the central nervous system and produce the sympathoexcitation (12).

Superoxide may contribute to increased sympathetic outflow, diminish the bioavailability of nitric oxide, and limit the sympathoinhibitory effects. Treatment with the cell membrane-permeable SOD mimetic Tempol decreases RSNA in both normotensive and hypertensive rats (38, 39). Viral transfection of SOD attenuates the response to central ANG II (44). To determine the effect of SOD overexpression (over 7 days) in the diabetic state, we transfected CuZnSOD adenovirus into the PVN of control and diabetic rats. The effects of AdCuZnSOD transfection showed a decrease in the excitatory effect of ANG II in the PVN. In diabetic rats injected with AdCuZnSOD, the response to ANG II injection into the PVN was significantly reduced compared with that of the diabetic + AdβGal group. These results indicate that superoxide plays an important role during ANG II-induced sympathoexcitation in diabetes.

The potential mechanisms responsible for an upregulation of AT1 receptors and superoxide within the PVN in diabetes remain uncertain. In the diabetic state, glucose-mediated upregulation of angiotensin and oxidative stress have been implicated in the pathogenesis of several vascular complications of diabetes, including diabetic neuropathy (24). It has been reported that in response to chronic hyperglycemia, the activity of ANG II is significantly upregulated in peripheral tissue (33). High glucose simulates angiotensinogen synthesis and ROS generation in renal tubular cells (16). It is possible that this high level of ANG II in the plasma may also have central effects, perhaps via the PVN as mentioned above (12). This, however, is speculative at this time. Also, several studies have shown a role for central and peripheral humoral factors such as interleukin (IL)-β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in the development and progression of diabetic neuropathy. Toxic effects of IL-β and TNF-α increase ROS generation and lead to oxidative damage during diabetes (6, 31). All of these alterations may induce the compensatory responses in the cardiovascular and autonomic centers. Further studies are required to determine the cellular mechanisms of action of ANG II and superoxide in the PVN and their interactions with other neurotransmitters.

As we know, superoxide generation in the brain does not only occur specifically within the PVN in STZ-induced diabetic rats. Some studies have shown increased superoxide generation in other brain areas, including cerebral cortex and hippocampus (30). The number of NADPH-positive neurons was increased in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, striatum, and dorsolateral periaqueductal grey of diabetic rats. However, no study to date has shown the involvement of other autonomic nuclei in STZ diabetic model. The present study is focused on only a specific site within the central nervous system (i.e., PVN). Other sites in the brain may also be important but remain to be examined.

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that superoxide contributes to the enhanced ANG II-mediated signaling in the PVN involved with the exaggerated sympathoexcitation in STZ-induced diabetes. Because sympathoexcitation contributes to the deterioration of the diabetic state, a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms involved in sympathoexcitation will help to uncover new therapies for the sympathetic dysfunction in diabetes.

Perspective and Significance

The RAS system is clearly activated in diabetes along with the sympathetic nervous system. The efficacy and utility of the RAS inhibition in clinical diabetes emphasizes the importance of this system in the cardiovascular complications of diabetes. The present study shows that altered ANG II and oxidative stress within the PVN may contribute to the elevated sympathetic nerve activity in the diabetic state. In the PVN, there are multiple other excitatory neurotransmitters/substances that are involved in sympathetic outflow and cardiovascular function, including glutamate, norepinephrine, dopamine, and cytokines. The details of the intricate and complex interactions among these excitatory factors, ANG II, and superoxide remain to be investigated. Nevertheless, this study demonstrates an important role for the RAS system within the PVN on sympathetic outflow and thus may contribute to the cardiovascular complications that are manifested during diabetes.

GRANTS

This work is supported by an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The technical assistance of Xuefei Liu and Lirong Xu is greatly appreciated. We thank Dr. Robin Davisson for access to the AdCuZnSOD.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bakris G. Are there effects of renin-angiotensin system antagonists beyond blood pressure control? Am J Cardiol 105: 21A–29A, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Borges GR, de Oliveira M, Salgado HC, Fazan R., Jr Myocardial performance in conscious streptozotocin diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol 5: 26, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brooks VL. Interactions between angiotensin II and the sympathetic nervous system in the long-term control of arterial pressure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 24: 83–90, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang KS, Lund DD. Alterations in the baroreceptor reflex control of heart rate in streptozotocin diabetic rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol 18: 617–624, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chappey O, Dosquet C, Wautier MP, Wautier JL. Advanced glycation end products, oxidant stress and vascular lesions. Eur J Clin Invest 27: 97–108, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen H, Li XY, Epstein PN. MnSOD and catalase transgenes demonstrate that protection of islets from oxidative stress does not alter cytokine toxicity. Diabetes 54: 1437–1446, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen QH, Toney GM. AT1-receptor blockade in the hypothalamic PVN reduces central hyperosmolality-induced renal sympathoexcitation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R1844–R1853, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dahlöf B, Devereux R, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Hedner T, Ibsen H, Julius S, Kjeldsen S, Kristianson K, Lederballe-Pedersen O, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wedel H. The Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction (LIFE) in Hypertension study: rationale, design, and methods. The LIFE Study Group. Am J Hypertens 10: 705–713, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Esler M. The sympathetic system and hypertension. Am J Hypertens 13, Suppl: 99S–105S, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Esler M, Kaye D. Sympathetic nervous system activation in essential hypertension, cardiac failure and psychosomatic heart disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 35, Suppl 4: S1–S7, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ewing DJ. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy and the heart. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 30, Suppl: S31–S36, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferguson AV, Renaud LP. Systemic angiotensin acts at subfornical organ to facilitate activity of neurohypophyseal neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 251: R712–R717, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fogari R, Mugellini A, Zoppi A, Derosa G, Pasotti C, Fogari E, Preti P. Influence of losartan and atenolol on memory function in very elderly hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens 17: 781–785, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Griendling KK, Ushio-Fukai M. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of angiotensin II signaling. Regul Pept 91: 21–27, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Head GA. Role of AT1 receptors in the central control of sympathetic vasomotor function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 23: S93–S98, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hsieh TJ, Zhang SL, Filep J, Tang SS, Ingelfinger JR, Chan JSD. High glucose stimulates angiotensinogen gene expression via reactive oxygen species generation n rat kidney proximal tubular cells. Endocrinology 143: 2975–2985, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kleinert S. HOPE for cardiovascular disease prevention with ACE-inhibitor ramipril. Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation. Lancet 354: 841, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krukoff TL, Patel KP. Alterations in brain hexokinase activity associated with streptozotocin-induced diabetic mellitus in the rat. Brain Res 522: 157–160, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li DP, Chen SR, Pan HL. Angiotensin II stimulates spinally projecting paraventricular neurons through presynaptic disinhibition. J Neurosci 23: 5041–5049, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li P, Morris M, Diz DI, Ferrario CM, Ganten D, Callahan MF. Role of paraventricular angiotensin AT1 receptors in salt-sensitive hypertension in mRen-2 transgenic rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 270: R1178–R1181, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li YF, Wang W, Mayhan WG, Patel KP. Angiotensin-mediated increase in renal sympathetic nerve discharge within the PVN: role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R1035–R1043, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔCT) method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McKinley MJ, Gerstberger R, Mathai ML, Oldfield BJ, Schmid H. The lamina terminalis and its role in fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. J Clin Neurosci: 289–301, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Obrosova IG. How does glucose generate oxidative stress in peripheral nerve? Int Rev Neurobiol 50: 3–35, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Palkovits M, Brownstein M. Brain microdissection techniques. In: Brain Microdissection Techniques, edited by Cuello AE. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patel KP, Knuepfer M. Effect of afferent renal nerve stimulation on blood pressure and heart rate and noradrenergic activity in conscious rats. J Auton Nerv Syst 17: 121–130, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patel KP, Zhang PL. Baroreflex function in streptozotocin (STZ) induced diabetic rats. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 27: 1–9, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Orlando, FL: Academic, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perin PC, Maule S, Quadri R. Sympathetic nervous system, diabetes, and hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens 23: 45–55, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Revsin Y, Saravia F, Roig P, Lima A, de Kloet ER, Homo-Delarche F, De Nicola AF. Neuronal and astroglial alterations in the hippocampus of a mouse model for type 1 diabetes. Brain Res 1038: 22–31, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sekido H, Suzuki T, Jomori T, Takeuchi M, Yabe-Nishimura C, Yagihashi S. Reduced cell replication and induction of apoptosis by advanced glycation end products in rat Schwann cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 320: 241–248, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seshiah PN, Weber DS, Rocic P, Valppu L, Taniyama Y, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II stimulation of NAD(P)H oxidase activity: upstream mediators. Circ Res 91: 406–413, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tikellis C, Wookey PJ, Candido R, Andrikopoulos S, Thomas MC, Cooper ME. Improved islet morphology after blockade of the renin-angiotensin system in the ZDF rat. Diabetes 53: 989–997, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tomlinson KC, Gardiner SM, Bennett T. Blood pressure in streptozotocin-treated Brattleboro and Long-Evans rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 258: R852–R859, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ustinova EE, Barrett CJ, Sun SY, Schultz HD. Oxidative stress impairs cardiac chemoreflexes in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H2176–H2187, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang G, Anrather J, Huang J, Speth RC, Pickel VM, Iadecola C. NADPH oxidase contributes to angiotensin II signaling in the nucleus tractus solitarius. J Neurosci 24: 5516–5524, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weekers L, Krzesinski JM. Clinical study of the month. Nephroprotective role of angiotensin II receptor antagonists in type 2 diabetes: results of the IDNT and RENAAL trials. Rev Med Liege 56: 723–726, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu H, Fink GD, Chen A, Watts S, Galligan JJ. Nitric oxide-independent effects of Tempol on sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in normotensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H975–H980, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu H, Fink GD, Galligan JJ. Nitric oxide-independent effects of Tempol on sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in DOCA-salt rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H885–H892, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang PL, Patel KP. Blunted diuretic and natriuretic responses to central administration of clonidine in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes 40: 338–343, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang ZH, Francis J, Weiss RM, Felder RB. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system excites hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus neurons in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H423–H433, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zheng H, Mayhan WG, Bidasee KR, Patel KP. Blunted nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of sympathetic nerve activity within the paraventricular nucleus in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R992–R1002, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zimmerman MC, Davisson RL. Redox signaling in central neural regulation of cardiovascular function. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 84: 125–149, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Lang JA, Sinnayah P, Ahmad IM, Spitz DR, Davisson RL. Superoxide mediates the actions of angiotensin II in the central nervous system. Circ Res 91: 1038–1045, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Hypertension caused by angiotensin II infusion involves increased superoxide production in the central nervous system. Circ Res 95: 210–216, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zimpelmann J, Kumar D, Levine DZ, Wehbi G, Imig JD, Navar LG, Burns KD. Early diabetes mellitus stimulates proximal tubule renin mRNA expression in the rat. Kidney Int 58: 2320–2330, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]