Abstract

OBJECTIVES/HYPOTHESIS

Mortality for black males with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is twice that of white males or females. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-active HNSCC, defined by the concurrent presence of high-risk type HPV DNA and host cell p16INK4a expression, is associated with decreased mortality. We hypothesized that prevalence of this HPV-active disease class would be lower in black HNSCC patients compared to white patients.

STUDY DESIGN

Multi-institutional retrospective cohort analysis.

METHODS

Real-time PCR was used to evaluate for high-risk HPV DNA presence. Immunohistochemistry for p16INK4a protein was used as a surrogate marker for HPV oncoprotein activity. Patients were classified as HPV-negative (HPV DNA-negative, p16INK4a low), HPV-inactive (HPV DNA-positive, p16INK4a low) and HPV-active (HPV DNA-positive, p16INK4a high). Overall survival and recurrence rates were compared by Fisher’s exact test and Kaplan-Meier analysis.

RESULTS

There were 140 patients with HNSCC who met inclusion criteria. Self-reported ethnicity was white (115), black (25), and other (0). Amplifiable DNA was recovered from 102/140 patients. The presence of HPV DNA and the level of p16INK4a expression were determined and the results were used to classify these patients as HPV-negative (44), HPV-inactive (33) and HPV-active (25). Patients with HPV-active HNSCC had improved overall 5-year survival (59.7%) compared to HPV-negative and HPV-inactive patients (16.9%) (P=0.003). Black patients were less likely to have HPV-active disease (0%) compared to white patients (21%), P=0.017.

CONCLUSIONS

The favorable HPV-active disease class is less common in black than in white patients with HNSCC, which appears to partially explain observed ethnic health disparities.

Keywords: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, human papillomavirus, etiology, ethnic disparities

INTRODUCTION

Black males have a higher incidence of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) than any other racial/gender group and suffer a mortality rate that is twice that observed in white males or females1–5. A disparity in access to care has been hypothesized as an explanation for the higher HNSCC mortality in black patients.3,4 Recently, however, Settle et al. published a landmark study linking ethnic health disparities in HNSCC to a positive test for human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in tumor samples6. HPV infection is a favorable prognostic indicator for HNSCC7–10, and differential overall survival for black patients in this study was driven by lower prevalence of HPV infection6.

We previously demonstrated that high levels of p16INK4a, a cell cycle regulator linked to biological activity of HPV oncoproteins (reviewed in 11), was a more robust prognostic indicator than the presence of HPV DNA alone8. The work led to the definition of three classes of tumors that are histopathologically similar but differ in molecular phenotype: (1) HPV-negative (DNA negative, p16INK4a negative), (2) HPV-inactive (DNA positive, p16INK4a negative), and (3) HPV-active (DNA positive, p16INK4a positive)8,12. Only HPV-active (and not HPV-inactive) HNSCC is associated with improved overall and disease-specific survival8. Here, we apply the three-class model to the investigation of ethnic health disparities for HNSCC. In agreement with Settle et al.6, we find that the prevalence of HPV DNA is lower in black HNSCC patients than in white, although the difference was not significant in our cohort (P=0.12). However, the difference between black and white patients was significant when p16INK4a status was also considered (P=0.01). Correlation of molecular data with clinical outcomes indicates that HPV-active status, not the presence of HPV DNA per se, drove overall survival and recurrence rates in this group of HNSCC patients. This immunohistochemically-based p16INK4a detection procedure is widely available and the results should thus be transposable to clinical practice in a variety of settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Inclusion criteria at Institution 1 (Yale University) were presentation with primary or recurrent histologically confirmed squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx between 1980 and 1999 and treatment with primary external beam radiotherapy (RT) or gross total surgical resection and postoperative RT at Yale-New Haven Hospital, a 900+ bed academic medical center which serves as a tertiary referral center in the northeastern United States. Exclusion criteria included presentation with metastatic disease, failure to receive full course of radiation therapy and unavailability of archival tumor tissue. Inclusion criteria at Institution 2 (Medical College of Georgia (MCG)) were presentation with histologically confirmed HNSCC between 2004 and 2007 and enrollment in a voluntary tissue/tumor banking registry at MCG Hospital, a 600+ bed academic medical center that serves as a tertiary referral center in the southeastern United States. Biopsy specimens were obtained pre- chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. The project was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at each institution.

HPV DNA Detection

For the Yale cohort, DNA was extracted from 0.6 mm tissue cores via a Chelex-100/Proteinase K protocol as previously described13. For the MCG cohort, frozen sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and enriched for tumor cells by Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) using an Arcturus PixCell IIe microscope (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale CA). The polymer film with adherent tumor cells were placed into a microcentrifuge tube containing 20 μg/ml Proteinase K (Gentra PureGene DNA Extraction Kit, Qiagen Corporation, Valencia CA) and incubated for 3 hours at 60 °C. All specimens were analyzed for amplifiable genomic DNA by SYBR Green qPCR using primers targeting a 161 nucleotide (nt) region of the β-globin gene (refer to Supporting Information, Supplementary Table I). For the Yale cohort, HPV detection was by SYBR Green qPCR using primers directed against a 109 bp region of the HPV16 E6 gene as described8,14 (Supplementary Table I). For the Georgia cohort, an HPV type-specific TaqMan-based qPCR assay was performed using primers directed against an 82 nt region of the HPV16 E7 gene and an 81 bp region of the HPV18 E7 gene (Supplementary Table I). Details are given in Supporting Information.

p16INK4a Expression Status

For the Yale cohort, two-fold redundant tissue microarray (TMA) was constructed as previously described8 and included cores from HPV 18-positive HeLa and HPV 16-positive Caski cell lines fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin as positive controls. For the MCG cohort, individual sections (4 μm) were cut from paraffin blocks and mounted. Immunohistochemical detection of p16INK4a expression using anti-p16INK4a mouse monoclonal antibody was performed as described in Supporting Information. Slides were read independently by two investigators (PMW and MAM for the Georgia cohort and as previously described8 for the Yale cohort) and consensus scoring was used to classify samples as p16INK4a-positive (strong, diffuse staining) or p16INK4a-negative (weak or absent staining)15.

Tumor Classification and Statistical Analysis

Comparison of classification status with the clinical and demographic variables was made by contingency table analysis with Fisher’s Exact test (ethnicity, gender, alcohol use, tobacco use) and Mantel-Haensel Chi Square (Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) stage and histologic grade). Comparison of classification status with age was made by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Disease-free survival, overall survival and local recurrence were assessed by Kaplan-Meier estimates of the survivor function with log-rank for determining statistical significance. Relative risk and prognostic independence was assessed by a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model with clinical and demographic variables, including HPV classification, TNM stage, histologic grade and ethnicity. Analysis was performed using a forward progression model with dummy variable encoding for all categorical variables. All statistical calculations were performed with SPSS 14.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL) and where appropriate were two-tailed.

RESULTS

Patient demographics and HPV status

There were 140 patients with HNSCC who met inclusion criteria, drawn from two separate hospitals in geographically distinct regions of the United States. Table I indicates the demographic characteristics of the study cohort, including age, gender, ethnicity, TNM stage, grade, and primary versus recurrent tumor type. Institution 1 (Yale) had 116 patients included in this study, and Institution 2 (MCG) had 24 patients. There were no significant differences in demographic or clinical variables between institutions (data not shown).

Table I.

Patient demographics and comparison by HPV class.

| All patients | p16INK4a/HPV available¶ | HPV-negative | HPV-inactive | HPV-active | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 41 – 79 (mean 60.3) | 140 | 102 | 41–79 (mean 60.4) | 43–77 (mean 60.7) | 41–71 (mean 58.0) | 0.53 |

| Gender | Male | 106 | 74 | 28 | 25 | 21 | 0.19 |

| Female | 34 | 28 | 16 | 8 | 4 | ||

| Ethnicity | White | 115 | 86 | 34 | 27 | 25 | 0.017 * |

| Black | 25 | 16 | 10 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| TNM stage | Stage 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.008 ** |

| Stage 2 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Stage 3 | 40 | 32 | 8 | 17 | 7 | ||

| Stage 4 | 80 | 57 | 27 | 13 | 17 | ||

| Grade† | Well diff. | 8 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0.014 * |

| Moderately diff. | 65 | 44 | 23 | 16 | 5 | ||

| Poorly diff. | 50 | 40 | 14 | 10 | 16 | ||

| Tumor type‡ | Primary | 119 | 88 | 41 | 24 | 23 | 0.006 ** |

| Recurrent | 17 | 12 | 2 | 9 | 1 | ||

Significant at P=0.05 level,

significant at P=0.01 level.

DNA extraction and HPV detection was successful in 106 patients, p16INK4a expression was determined in 126 patients, and there were 102 patients with both HPV and p16INK4a data available for classification by the 3-class system.

Excludes 17 patients (11 with p16INK4a/HPV data available) where grade was not recorded.

Excludes 4 patients (2 with p16INK4a/HPV data available) where tumor type was not recorded. Diff. = differentiated.

The presence of high-risk type HPV 16 or HPV 18 DNA was determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction using primers directed against E6 and E7 genes as described in Materials and Methods. The presence of amplifiable DNA in the samples was determined based on the ability to detect the cellular β-globin gene. Amplifiable DNA was obtained from 106/140 (76%) of patients. Expression of p16INK4a was determined for 102 of these 106 samples (96%). Based on these results, patients were classified using the 3-class system described previously (Table II) 8. There were 44/102 (43.1%) HPV-negative (HPV16 DNA-negative, p16INK4a-negative), 33/102 (32.4%) HPV-inactive (HPV16 DNA-positive, p16INK4a-negative) and 25/102 (24.5%) HPV-active (HPV16 DNA-positive, p16INK4a-expressing) patients.

Table II.

Classification system

| HPV DNA negative | HPV DNA-positive | |

|---|---|---|

| p16INK4a low | HPV-negative | HPV-inactive |

| p16INK4a high | undefined (not observed) | HPV-active |

Several significant correlations were observed between HPV class and the demographic and clinical variables in Table I. Notably, white patients were significantly more like to have HPV-active disease than black patients (29% versus 0%, P=0.017). Increasing TNM stage was also associated with HPV-active classification (P=0.008), as was poorly differentiated grade (P=0.014).

We also observed a novel relationship between HPV class and primary versus recurrent tumor type. The majority of recurrent tumors were in the HPV-inactive class, where viral DNA was detected but p16INK4a overexpression was not. There were 9/12 (75%) recurrent tumors assigned to this class, versus 24/88 (27%) primary tumors. The biological significance of this observation remains to be ascertained.

Survival and recurrence by ethnicity

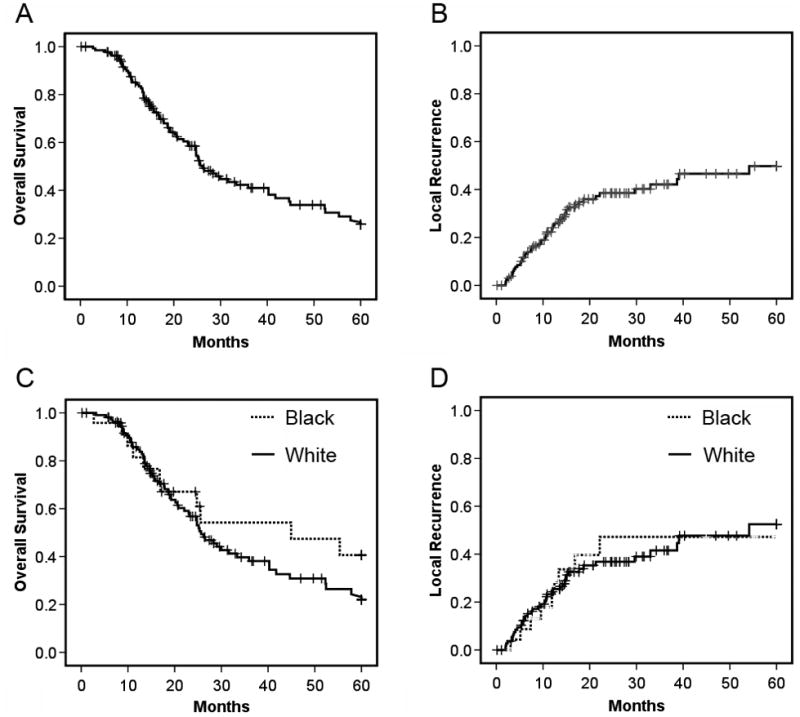

We estimated overall survival and local recurrence using Kaplan-Meier estimates of the survival function with log-rank for determining statistical significance (Figure 1). The median survival for the entire cohort was 26.2 months (95% CI = 21.6–30.8 months), and the 5-year local recurrence rate was 49.3 ± 11.7%. When data were stratified by ethnicity, median survival was found to be longer for black than for white patients (44.9 months versus 25.7 months) but the difference was not significant (P=0.26). The 5-year local recurrence rates for black versus white patients were very similar (52.5 ± 14.4% versus 47.2 ± 23.0% respectively).

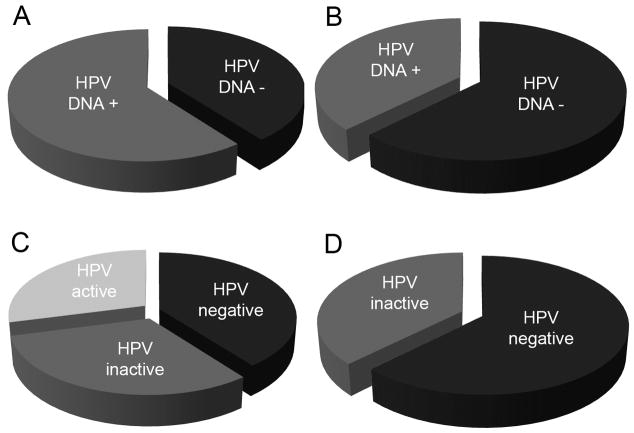

Fig. 1. Overall survival and local recurrence rates.

(A, B). Overall survival and local recurrence rates for the entire cohort (n=140) for a five year period post-diagnosis. (C, D) Overall survival and local recurrence rates stratified by patient ethnicity. Differences between ethnic groups were not significant (P=0.26, P=0.96 respectively).

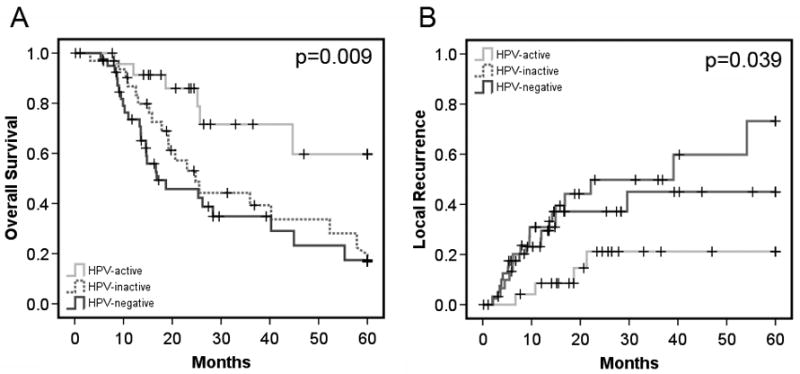

Survival and recurrence by HPV classification

We performed similar analyses of survival and local recurrence for the subset of 102 patients who could be classified by HPV status (Figure 2). Consistent with prior data from our group and others8,16,17, HPV-active classification (HPV DNA and p16INK4a overexpression) was associated with significantly greater median survival than the other two groups (median not reached at 60 months, versus 24.8 months for HPV-inactive and 16.8 months for HPV-negative, P=0.009). HPV-active classification was associated with a similar advantage in local recurrence rate (21.2% ±18.6% for HPV-active, versus 73.2% ±26.1% for HPV-inactive and 45% ±20.0% for HPV-negative, P=0.039).

Fig. 2. Survival and local recurrence rates stratified by HPV class.

(A) Overall survival rates for HPV-active, HPV-inactive, and HPV-negative patients as indicated. (B) Local recurrence rates for patients in each class as indicated.

Relationship between ethnicity and HPV status

Figures 3A and 3B show the prevalence of HPV DNA in white and black patients. There was a trend for higher prevalence in white patients (60.2%) compared to black patients (38.8%), but the difference was not significant (P=0.12). When compared using the three-class model, however, the fraction of patients in the HPV-active class (concomitant presence of HPV16 DNA and p16INK4a) differs markedly in the two ethnic groups. Whereas nearly half of the HPV-positive white patients fell into the HPV-active class (p16INK4a-positive) (Figure 2C) none of the black patients were p16INK4a-positive (Figure 2D), a significant difference (P=0.017).

Fig. 3. Comparison of HPV prevalence and ethnicity.

(A, B), Prevalence of HPV 16 DNA in patients stratified by ethnicity. A, white, B, black. Difference was not significant (P=0.12). (C, D), HPV status using 3-class system, stratified by ethnicity. C, white, D, black. Difference in the frequency of the HPV-active class between white and black patients was significant (P =0.017).

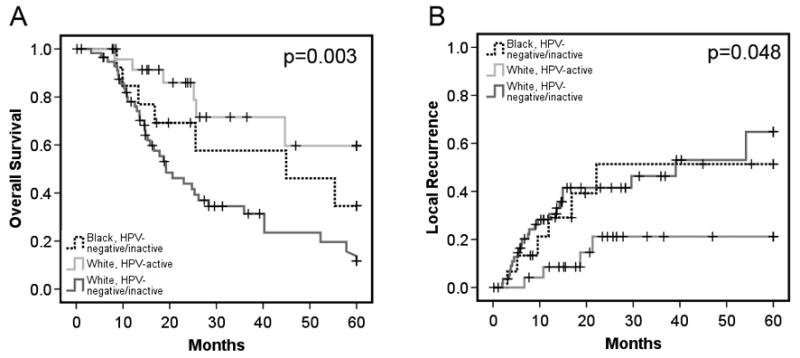

Survival and recurrence by ethnicity

Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to analyze survival and local recurrence rates stratified by a combination of ethnicity and HPV class (Figure 4). The HPV negative/inactive white patients (who were pooled for the analysis in Figure 4) had the shortest median survival of any group (19.2 months, 95% CI 12.9–25.6 months) and the highest recurrence rate (64.8 ± 23.8%). The HPV negative/inactive black patients actually fared somewhat better (median survival 44.9 months, 95% CI 4.9–85.0 months), although the difference was not significant (P = 0.11). As indicated previously (Figure 2) the HPV-active white patients had the best outcomes (median survival not reached at 60 months, local recurrence rate 21.2% ± 18.6%). The difference between HPV-active and HPV-inactive/negative white patients was significant (P=0.001), although the difference with HPV-inactive/negative black patients was not, perhaps reflecting the small number of black patients in the cohort (P= 0.23).

Fig. 4. Survival and local recurrence rates stratified by both ethnicity and HPV class.

(A) Overall survival rates for black and white patients, stratified by HPV-active versus HPV-negative/inactive as indicated. (B) Local recurrence rates for patients in each class as indicated.

Multivariate analysis of the relationship between outcomes, ethnicity and other clinical variables

We investigated potential confounding effects due to clinical parameters other than ethnicity on survival and recurrence by performing a Cox multivariate analysis. Clinical variables considered were ethnicity, TNM stage, histologic grade, primary versus recurrent tumor type, and HPV class. HPV-active class (compared to both HPV-negative, P=0.002, and HPV-inactive, P=0.015) and white ethnicity (P=0.050) were independently associated with improved survival. We further explored this relationship by testing interaction terms within the Cox model. The interaction term for ethnicity*HPV-active was significant in univariate analysis (P=0.002) but because of co-linearity with HPV-class it could not be included in the multivariate model. Similarly, for local recurrence recurrent tumor type (P=−0.004) and HPV-inactive versus HPV-active class (P=0.034) were independently associated with increased local recurrence but ethnicity was not (P=0.71). These data are summarized in Table III.

Table III.

Multivariate survival analysis (Cox regression)

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival | ||||

| HPV/p16 class | HPV active | (reference category) | ||

| HPV-inactive | 4.2 | 1.3 – 13.4 | 0.015* | |

| HPV-negative | 5.6 | 1.9 – 16.6 | 0.002** | |

| TNM stage | stage 1 | 1.2 | 0.1 – 12.1 | 0.86 |

| stage 2 | 0.5 | 0.2 – 1.3 | 0.14 | |

| stage 3 | 0.4 | 0.2 – 0.9 | 0.032* | |

| stage 4 | (reference category) | |||

| Histologic grade | poorly diff. | 1.0 | 0.4 – 2.7 | 0.96 |

| moderately diff. | 0.6 | 0.2 – 1.7 | 0.37 | |

| well diff. | (reference category) | |||

| Tumor type (recurrent vs primary) | 1.1 | 0.4 – 3.2 | 0.89 | |

| Ethnicity (white vs black) | 0.4 | 0.2 – 1.0 | 0.05* | |

| Local Recurrence | ||||

| HPV/p16INK4a class | HPV active | (reference category) | ||

| HPV-inactive | 4.2 | 1.0 – 18.4 | 0.056 | |

| HPV-negative | 4.4 | 1.1 – 17.3 | 0.034* | |

| TNM stage | stage 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 – 0.0 | 0.98 |

| stage 2 | 0.6 | 0.2 – 2.3 | 0.45 | |

| stage 3 | 0.9 | 0.4 – 2.2 | 0.80 | |

| stage 4 | (reference category) | |||

| Grade | poorly diff. | 1.2 | 0.4 – 4.0 | 0.74 |

| moderately diff. | 0.4 | 0.1 – 1.5 | 0.18 | |

| well diff. | (reference category) | |||

| Tumor type (recurrent vs primary) | 4.2 | 1.6 – 11.2 | 0.004** | |

| Ethnicity (white vs black) | 0.8 | 0.3 – 2.5 | 0.71 | |

Significant at P=0.05 level,

significant at P=0.01 level. Diff .= differentiated. For TNM staging dummy variable coding, TNM stage 4 was used as the reference category as this was the most common stage cancer.

DISCUSSION

The present work demonstrates the striking absence of a favorable subset of HPV-associated HNSCC among black patients, concordant across two academic medical centers in different geographic regions of the United States. We used a three-class model based both on physical presence of HPV DNA and on biological activity of HPV oncoproteins, as evidenced by overexpression of p16INK4a. This model distinguishes between HPV-active disease, HPV-negative disease, and a separate category of HPV-inactive disease, where viral DNA is present but the program of viral oncogenesis is not engaged or where there is a concomitant p16INK4a deletion. HPV-active disease was significantly less prevalent in black patients than in white patients (0% versus 29%). By contrast, HPV-inactive disease was common in patients of both black and white ethnicity (31% and 38%, respectively. Significant interaction between HPV status, ethnicity, and clinical outcomes was evident only when HPV-active and HPV-inactive subsets were distinguished. Multivariate analysis shows that HPV-active status, and not ethnicity, is a principal contributor to differences in overall survival and recurrence rates among patient groups.

The mechanism underlying the different prevalence of HPV-active disease in different ethnic groups is not understood. However, occurrence of HPV-inactive disease in both the black and white groups indicates that the patients in both groups suffer exposure to, and initial infection with, HPV. The data suggest, therefore, that white patients may be more susceptible to progression from HPV infection to HPV-associated HNSCC, or alternatively that black patients may be protected. It does not appear that this differential susceptibility extends to cervical cancer, a disease that is universally HPV-associated. Black women in the United States have an increased prevalence of both high-risk HPV18 and cervical cancer19 compared to hispanic and white women.

It is likely that the immune response plays an important role in controlling susceptibility to progression of HPV-related disease (reviewed in 20). In this context, it is notable that several studies have shown that white males and females are more likely to engage in oral sex compared to blacks21,22. Conversely, black females are more likely to engage in early intercourse compared to white and hispanic females23. Whether early genital HPV infection may lend protective immunity against subsequent oropharyngeal HPV infection, or vice versa, remains to be investigated.

A better understanding of the interaction between HPV status, ethnicity, and clinical outcomes is important to the optimal design of prevention and therapeutic strategies. HPV-targeted therapeutic vaccines are currently undergoing clinical trials in head and neck cancer patients. Currently, these trials stratify patients based only on HPV DNA presence. The use of p16INK4a immunohistochemistry to existing protocols for identification of HPV active disease would seem to be of vital importance to identify those patients who are most likely to benefit from HPV-targeted therapeutic strategies.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of a more favorable, HPV-active disease subset is lower in black HNSCC patients than in white patients. This is the second report of ethnic differences in prevalence of HPV-associated HNSCC. Although the two studies differ in methodology and patient populations, they reach the same overall conclusion that a lower incidence of a more favorable HPV-associated disease subset contributes to the well-established ethnic disparity in HNSCC outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a US Public Health Service Award, CA 95941. WSD is an Eminent Scholar of the Georgia Research Alliance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Al-Othman MO, Morris CG, Logan HL, Hinerman RW, Amdur RJ, Mendenhall WM. Impact of race on outcome after definitive radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2003;98:2467–2472. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodwin WJ, Thomas GR, Parker DF, et al. Unequal burden of head and neck cancer in the United States. Head Neck. 2007 doi: 10.1002/hed.20710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gourin CG, Podolsky RH. Racial disparities in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1093–1106. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000224939.61503.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yen KL, Horner MJ, Reed SG, et al. Head and neck cancer disparities in South Carolina: descriptive epidemiology, early detection, and special programs. J S C Med Assoc. 2006;102:192–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molina MA, Cheung MC, Perez EA, et al. African American and poor patients have a dramatically worse prognosis for head and neck cancer: an examination of 20,915 patients. Cancer. 2008;113:2797–2806. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Settle K, Posner MR, Schumaker LM, et al. Racial Survival Disparity in Head and Neck Cancer Results from Low Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus Infection in Black Oropharyngeal Cancer Patients. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2009 doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, et al. Molecular classification identifies a subset of human papillomavirus--associated oropharyngeal cancers with favorable prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:736–747. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchie JM, Smith EM, Summersgill KF, et al. Human papillomavirus infection as a prognostic factor in carcinomas of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:336–344. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W, Thompson CH, O’Brien CJ, et al. Human papillomavirus positivity predicts favourable outcome for squamous carcinoma of the tonsil. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:553–558. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Human papillomaviruses. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2007;90:1–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Kountourakis P, et al. Defining molecular phenotypes of human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Validation of three-class hypothesis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:382–389. e381. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coombs NJ, Gough AC, Primrose JN. Optimisation of DNA and RNA extraction from archival formalin-fixed tissue. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:e12. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.16.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch WM, Lango M, Sewell D, Zahurak M, Sidransky D. Head and neck cancer in nonsmokers: a distinct clinical and molecular entity. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1544–1551. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199910000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, et al. Prognostic significance of p16 protein levels in oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5684–5691. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klussmann JP, Gultekin E, Weissenborn SJ, et al. Expression of p16 protein identifies a distinct entity of tonsillar carcinomas associated with human papillomavirus. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:747–753. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63871-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong CS, Narasimhan B, Cao H, et al. The relationship between human papillomavirus status and other molecular prognostic markers in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn JA, Lan D, Kahn RS. Sociodemographic factors associated with high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:87–95. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000266984.23445.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker B, Figgs LW, Zahm SH. Differences in cancer incidence, mortality, and survival between African Americans and whites. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103 (Suppl 8):275–281. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s8275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frazer IH. Interaction of human papillomaviruses with the host immune system: a well evolved relationship. Virology. 2009;384:410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gates GJ, Sonenstein FL. Heterosexual genital sexual activity among adolescent males: 1988 and 1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32:295–297. 304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. [Accessed September 3, 2009];National Survey of Family Growth [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/NSFG.htm.

- 23.Hobfoll SE, Jackson AP, Lavin J, Britton PJ, Shepherd JB. Safer sex knowledge, behavior, and attitudes of inner-city women. Health Psychol. 1993;12:481–488. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.6.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.