Abstract

Topical ocular drug bioavailability is notoriously poor, in the order of 5% or less. This is a consequence of effective multiple barriers to drug entry, comprising nasolacrimal drainage, epithelial drug transport barriers and clearance from the vasculature in the conjunctiva. While sustained drug delivery to the back of the eye is now feasible with intravitreal implants such as Vitrasert™ (~6 months), Retisert™ (~3 years) and Iluvien™ (~3 years), currently there are no marketed delivery systems for long-term drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye. The purpose of this article is to summarize the resurgence in interest to prolong and improve drug entry from topical administration. These approaches include mucoadhesives, viscous polymer vehicles, transporter-targeted prodrug design, receptor-targeted functionalized nanoparticles, iontophoresis, punctal plug and contact lens delivery systems. A few of these delivery systems might be useful in treating diseases affecting the back of the eye. Their effectiveness will be compared against intravitreal implants (upper bound of effectiveness) and trans-scleral systems (lower bound of effectiveness). Refining the animal model by incorporating the latest advances in microdialysis and imaging technology is key to expanding the knowledge central to the design, testing and evaluation of the next generation of innovative ocular drug delivery systems.

The current ophthalmology market is primarily driven by age- and lifestyle-related diseases, such as macular degeneration, cataracts, diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma. Dry eye syndrome, inflammation and ocular allergies are also contributing significantly. Traditionally, antiglaucoma products held the major market share. Driven by demographic trends such as an increase in aged population and lifestyle factors, the overall market for ophthalmic therapeutics is expected to undergo considerable and consistent growth during the next decade. In the USA, cases of visual impairment and blindness due to age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) are expected to increase from 620,000 cases in 2010 to 1.7 million in 2050 [1]. While therapeutic agents are currently available for treating only the wet form of ARMD, new treatments are anticipated in the future for treating the more prevalent dry form of ARMD [2]. The global ophthalmic pharmaceutical market with registered sales of US$14 billion in 2009, is forecasted to grow at a double digit rate [3].

The principal challenge in advancing therapeutics for treating diseases of the front as well as back of the eye is attainment of effective drug concentration at the drug target for prolonged periods of time, whilst minimizing any side effects. In addition, enhancing patient adherence with drug therapy, especially for asymptomatic diseases such as glaucoma, poses another challenge. The main focus of this article is to update the noninvasive sustained delivery systems administered in the front of the eye. Reference to posterior ocular drug delivery will be made for those systems that show promise there. In this context, key advances in sustained back of the eye drug delivery using invasive delivery systems, such as intravitreal implants and drug suspensions, will be summarized.

Ocular pharmacokinetic studies & barriers to ocular drug delivery

It is routine for pharmaceutical manufacturers to assess drug pharmacokinetics following oral administration of the drug product in human subjects. This pharmacokinetic data is a critical part of the new drug application (NDA). However, for ocular drug products, there is no such requirement for pharmacokinetic studies in human subjects. This is because the relevant target or surrogate tissues, such as aqueous humor and vitreous humor, cannot be sampled serially in human subjects to assess pharmacokinetics. For the same reasons, even during drug product development, pharmacokinetic data are not obtained in humans. Instead, pharmacokinetic studies have routinely relied on the use of animal models with eye sizes comparable to humans, such as rabbit, dog, monkey and pig, with rabbit being the most commonly used species for pharmacokinetic studies. More recently, pharmacokinetic data are being collected in rodent models, since several rodent disease models are available [4–14]. It is now evident that topical ocular drug delivery differs between rabbit, monkey and human models, even at the level of tear concentrations [15]. Thus, it can be anticipated that intraocular concentrations between species will differ. However, with appropriate mathematical models and scaling approaches for the size of the eye and the animal model, pharmacokinetics in one species can probably be extrapolated to other species [7]. Even in the absence of such sophisticated models, animal models such as the rabbit are valuable in assessing the relative availability of a drug from various formulations during drug product development. Between species, it is likely that the relative pharmacokinetic performance of various formulations will hold true on several occasions.

A key challenge in ocular pharmacokinetics is serial sampling of target tissues such as aqueous humor, iris-ciliary body, retina and vitreous humor to plot the concentration–time profiles for estimating various pharmacokinetic parameters, including area under the curve (AUC), time to maximum tissue concentration (Tmax) and peak tissue concentration (Cmax). Unlike the systemic pharmacokinetic studies where serial sampling in surrogate tissue (plasma) is feasible, conventional ocular pharmacokinetic studies do not allow serial drug sampling from eye tissues. Therefore, as mentioned by Lee and Robinson [16], ocular pharmacokinetic experiments are expensive, time consuming and require a large number of animals to define the pharmacokinetics of a drug after a single topical dose. However, such pharmacokinetic data is essential and routinely presented to the US FDA in a NDA.

Given the aforementioned animal-intensive nature of preclinical pharmacokinetic analysis in the eye, there is a critical need to develop alternative approaches. Such approaches, albeit with limitations, include microdialysis and non-invasive pharmacokinetic analysis. Microdialysis techniques allow continuous sampling of aqueous and vitreous humors in the same eye, making it feasible to assess pharmacokinetic parameters in both fluids using one single animal [17]. Microdialysis is a probe-based sampling technique that allows the analysis of the sample from fluid compartments or tissue-interstitial fluid compartments to measure unbound or free drug concentrations. The basic principle of microdialysis is based on a capillary dialysis probe, wherein continuous transfer of soluble molecules occurs between tissue space and the fluid enclosed in the probe across a semipermeable membrane. Since only unbound drug can permeate the membrane, drug concentrations in the probe would be reflective of free drug concentrations in the tissue.

In ocular pharmacokinetic studies, the microdialysis probe is generally placed in liquid compartments of the eye, such as aqueous humor (anterior chamber microdialysis) and vitreous humor (posterior chamber microdialysis). For aqueous humor microdialysis, a linear probe is placed in the anterior chamber with the help of a 25-gauge (G) needle by inserting the needle across the cornea, above the limbus. A linear microdialysis probe is inserted through the needle and held on the other side. The needle is then retracted so that the probe is suspended in aqueous humor in the middle of the anterior chamber. The outlets of the probe are fixed to the tissue using surgical glue. For vitreous humor microdialysis, a concentric probe is used. This probe is placed in the middle of the vitreous cavity using a 22-G needle and a guiding canula. Samples can be collected from aqueous humor, vitreous humor or both compartments simultaneously. Perfusion of the above probes with isotonic buffer and collection of perfusate at regular time intervals allows serial sampling and continuous measurement of solute concentration in both aqueous humor and vitreous humor of the eye in a single animal [17]. These measurements, although routinely made in anesthetized animals [18], can also be made in conscious animals [19]. However, for assessing sustained drug delivery over several months, microdialysis may not be necessary, since sporadic sampling with a few animals is probably adequate. Furthermore, the microdialysis technique does not allow continuous drug level assessment in solid target tissues, such as the iris-ciliary body or the retina.

Currently, there is growing interest in non-invasive approaches for assessing pharmacokinetics in the eye. Some of these approaches are summarized in Table 1. Such approaches might eventually allow assessment of drug pharmacokinetics in human eyes. Key limitations of the various noninvasive techniques for pharmacokinetic analysis include low sensitivity and hence inability to detect the low drug concentrations anticipated in target tissues; poor depth resolution and, therefore, inability to distinguish target tissue layers such as choroid, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and neural retina and applicability to specific molecules or molecules with an imaging signal as opposed to any given drug molecule. While microdialysis allows analysis of readily diffusible low-molecular-weight drugs with good sensitivity in the fluid compartments of the eye, it is not suitable for drug analysis in target tissues such as the iris-ciliary body and retina. Traditional pharmacokinetic studies, on the other hand, require a large number of animals, while allowing drug analysis in multiple tissues with sensitive analytical methods. Due to the comprehensive nature of data provided by traditional pharmacokinetic studies, these are still the norm in NDAs related to ophthalmic products.

Table 1.

Comparison of various techniques for noninvasive or invasive assessment of ocular drug delivery and pharmacokinetics.

| Technique | Type | Drugs | Procedure | Sensitivity | Resolution | Errors | Human study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRI | Noninvasive | Applicable only for contrast agents, fluorinated (19F) compounds or drug molecules labeled with contrast agent | Continuous monitoring over time in live animals | Relatively low sensitivity | Spatial resolution is ~0.3 mm, in-plane. Does not allow the clear distinction of small ocular structure such as retina, ciliary body, and trabecular meshwork |

Tissue microenvironment affects relaxation time and hence the signal may give false results. Mobility artifacts |

Feasible with approved contrast agent and 19F compound |

| Positron emission tomography | Noninvasive | Applicable for fluorinated (18F) compounds or drugs labeled with 11C or 15O | Continuous monitoring over time in live animals | Relatively high sensitivity compared with MRI and single photon emission computed tomography but lower than traditional pharmacokinetics | Spatial resolution is ~1–2 mm. Does not allow the clear distinction of small ocular structure such as retina, ciliary body, and trabecular meshwork |

Feasible with fluorinated drugs or drugs labeled with with 11C or 15O | |

| Single photon emission computed tomography | Noninvasive | Applicable only for 99mTc and 111In-chelates | Continuous monitoring over time in live animals | Relatively low sensitivity | Spatial resolution is ~1–2 mm. Does not allow the clear distinction of small ocular structures such as retina, ciliary body, and trabecular meshwork |

||

| Raman spectroscopy | Noninvasive | Applicable only for drugs with distinct Raman signal |

Continuous monitoring over time in live animals | Relatively low sensitivity and depends on molecular properties of the drug. Able to detect sub-milligram to microgram levels in tissues | Spatial resolution is ~0.25 mm, in-plane Does not allow the clear distinction of small ocular structures such as retina, ciliary body, and trabecular meshwork |

Raman signal from tissue background may give artifacts and false positive results | Feasible with lower intensity light source. |

| Fluorophotometry | Noninvasive | Applicable only for fluorescent probes or drug molecules labeled with fluorescent probe (more specifically for fluorescein and similar molecules) | Continuous monitoring over time in live animals | More sensitivity than MRI and Raman spectroscopy, but low sensitivity when compared with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Can detect nanogram levels | Spatial resolution is ~0.25 mm in plane Does not allow the clear distinction of small ocular structures such as retina, ciliary body, and trabecular meshwork |

Background auto fluorescence of the tissue may give false positive results | Feasible |

| Microdialysis | Invasive | Most suitable for low molecular weight drugs | Continuous monitoring over time in live animals | Detection limited by drug diffusion through the probe, which declines with an increase in molecular size | Allows quantification of free drug in the aqueous and vitreous humors of the eye | Potential perturbations in drug levels due to probe insertion related injury | Not feasible |

| Traditional pharmacokinetics | Invasive | All types of drug molecules | Sacrifice of animals at each time point | High sensitivity and capable of detecting nanogram or even picogram levels in tissues | Allows quantification of drug in small tissues and even in subdivisions of tissue such as epithelium and stroma following dissection | Cross contamination and redistribution among tissues during and prior to dissection | Not feasible |

Once a suitable animal model, analytical method for the drug of interest and pharmacokinetic method are identified, it is feasible to estimate drug distribution from a delivery system or dosage form. In addition, drug bio-availability or the extent of drug absorption from a dosage form can potentially be estimated. Several previous reports on topical ocular drug delivery do not estimate the bioavailability in an appropriate manner. While the parameters AUC, Tmax and Cmax can be used to compare the relative bioavailability (relative extent of absorption) between various formulations, absolute bioavailability (actual fraction of the dose absorbed) can only be estimated based on direct drug dosing in the target tissue. For instance, absolute bioavailability in the aqueous humor can be estimated by comparing the dose-normalized AUCs between topical and intracameral doses, provided the drug clearance does not change between the two routes of administration and the doses used. Due to the intrusive nature of experimentation used for the assessment of ocular pharmacokinetics, very limited reports are available that actually estimate the absolute bioavailability of drug molecules in the aqueous humor after topical application. Microdialysis and noninvasive methods of pharmacokinetics (Table 1) might allow efficient estimation of such parameters with minimal use of animals. Rittenhouse et al. determined the AUC for propranolol HCl solution in the aqueous humor of dogs and rabbits using a microdialysis technique after topical and intracameral modes of administration [20]. The estimated absolute bioavailability of propranolol in the aqueous humor after topical application as an eye drop was 0.98 ± 0.55% in dogs and 4.5 ± 2.8% in New Zealand white rabbits. Thus, the bioavailability of even a lipophilic drug such as propranolol is very low in the aqueous humor following topical dosing. Despite the dedicated efforts of ophthalmic formulation scientists over the last four decades, the goal to increase ocular drug bioavailability from less than 5% to at least 15–20% has been met with only limited success. These efforts aim at either overcoming permeability barriers such as the cornea or overcoming drug loss such as precorneal clearance. The extent of delivery is expected to be much lower in the vitreous humor when compared with the aqueous humor after topical application. The absolute bioavailability in the vitreous humor after topical application can be estimated by comparing the dose-normalized AUCs between topical and intravitreal doses. In one study, the vitreal pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine A were evaluated in albino rabbits after intravitreal injection at a 10 μg dose [21]. In this study, the vitreous AUC0–48h was estimated to be 103.3 μg.h/g tissue. In another study, Acheampong et al. measured the AUC0–96h for cyclosporine in the vitreous humor after topical application of 100 μg of cyclosporine as an emulsion in albino rabbits [22]; the measured AUC was 0.022 μg.h/g tissue. Thus, the absolute bioavailability of cyclosporine in rabbit vitreous humor after topical application as an eye drop is, at most, 0.002%, since cyclosporine levels may have contributed more to the vitreous AUC between 48 and 96 h following intravitreal dosing.

Thus, drug bioavailability in the anterior and posterior segments is very limited. Key reasons for such low bioavailability include short precorneal residence time of an eye drop as well as multiple permeability barriers that a drug has to cross prior to reaching target eye tissues. Topically applied solutions clear rapidly from the rabbit eye surface, with a half-life of approximately 1.3 min [23]. As discussed later, delivery systems such as punctal plugs, contact lenses and scleral lenses are being designed to overcome the short precorneal residence time.

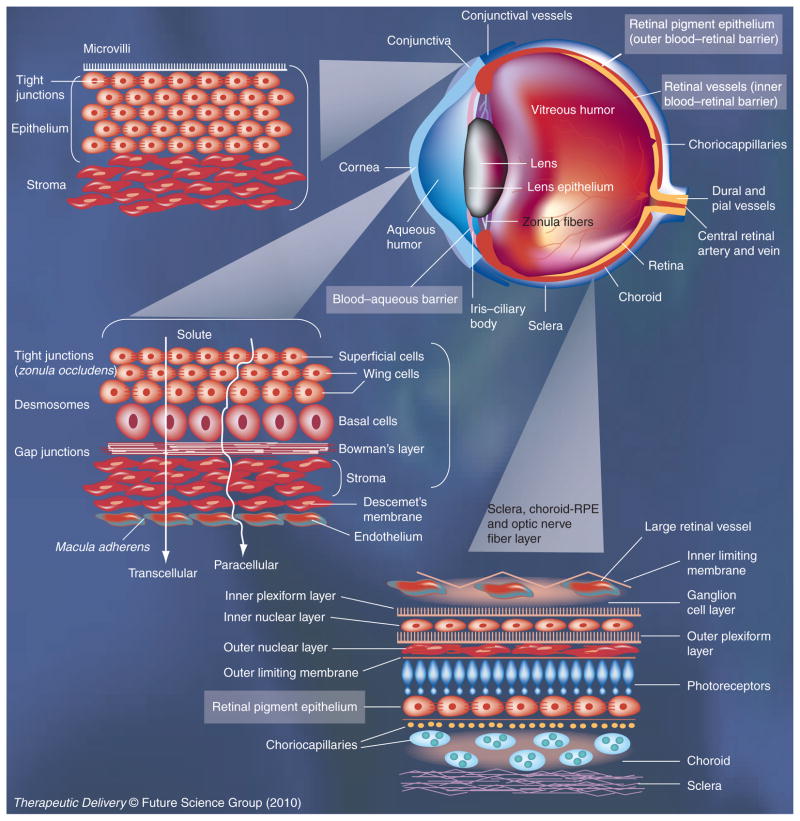

Permeability barriers are natural defense mechanisms of the eye against the entry of xenobiotics. As shown in Figure 1, several permeability barriers exist in the eye, limiting intraocular drug delivery. The cornea is a tight epithelial barrier that limits drug absorption owing to the presence of tight junctions and a multilayered structure that restricts movement of water and solutes [24]. Corneal permeability, however, is critical for topically applied drugs targeting tissues of the anterior segment of the eye, including aqueous humor, iris-ciliary body and the lens. The conjunctiva is another barrier that limits drug permeability due to the presence of tight junctions and multicellular architecture [25]. However, isolated conjunctiva is more permeable compared with the cornea [26]. In the living animal, drug entering this tissue might be cleared rapidly, due to the presence of blood circulation in the conjunctiva. In addition, episcleral blood supply can potentially clear the drug that crosses conjunctiva. The fraction of the dose escaping conjunctival and episcleral barriers can permeate across sclera, a fibrous, porous tissue that also allows permeability of macromolecules [27]. Key target tissues in the back of the eye include the choroid, RPE and retina. Key diseases afflicting the back of the eye include wet and dry ARMD and diabetic retinopathy. While trans-scleral transport places the drug in the proximity of choroid, to reach neural retina the drug has to cross the RPE, a monolayer of cells with tight junctions (outer blood–retinal barrier). For the drug to enter the retina from the systemic circulation, it has to cross the retinal blood vessels, with a tight monolayer of endothelial cells (inner blood–retinal barrier). Due to the presence of such formidable barriers, eye drops and systemic doses do not efficiently deliver a drug to the back of the eye tissues. However, when dosed at sufficiently high levels, some drugs may achieve therapeutic levels in tissues of the back of the eye after topical [28] and systemic [29] administrations. Intravitreal injections, however, are the norm to deliver drugs efficiently to the retina. Alternative less invasive approaches to the globe being investigated include periocular injections for trans-scleral delivery [27], as well as suprachoroidal administrations [30]. However, permeability barriers imposed by surface ocular tissues can potentially be overcome to some extent using prodrugs, penetration enhancers, iontophoresis, ultrasound, and nanoparticles, as discussed subsequently in this article.

Figure 1. Permeability barriers for ocular drug delivery.

Cornea and conjunctiva are key epithelial barriers encountered by topically administered drug molecules. A topically administered drug can reach the retina if it can traverse conjunctiva, sclera, choroid and the retinal pigment epithelium, in that order. Systemically administered drugs have to cross the blood–aqueous barrier to reach the intraocular tissues of the anterior segment of the eye. Systemic drugs have to cross the blood–retinal barriers, that is, the retinal pigment epithelium (outer blood–retinal barrier) or the retinal vasculature (inner blood–retinal barrier).

Figure modified with permission from [128] © Taylor & Francis Group.

A new generation of ophthalmic vehicles and delivery systems are summarized in Table 2. As evident, prodrugs of prostaglandins are being employed to enhance membrane permeability of topically administered drugs. Viscous and mucoadhesive vehicles are being employed in topical formulations to enhance precorneal drug retention. In order to treat back-of-the-eye disorders such as ARMD, intravitreally injectable aptamer (Macugen™) and antibody fragment (Lucentis™) formulations have been introduced. To reduce the frequency of intra-vitreal injections and to treat chronic back-of-the-eye disorders such as diabetic retinopathy and uveitis, injectable (Ozurdex™; Ileuvien™) or surgically placed (Vitrasert™; Retisert™) sustained release implants have been developed.

Table 2.

Some examples of ophthalmic drug-delivery systems approved by the US FDA.

| Product category | Description | Drug | Year of approval | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical delivery systems | ||||

| Ophthalmic solution (Acuvail™) | Preservative free 0.45% ketorolac tromethamine solution containing carboxymethylcellulose as viscosity enhancer | Ketorolac tromethamine | 2009 | NSAID for the treatment of pain and inflammation after cataract surgery |

| Ophthalmic solution (Lumigan™) | 0.03% ophthalmic solution of bimatoprost with 0.005% benzalkonim chloride as preservative | Bimatoprost (prodrug) | 2001 | Reduction of elevated IOP |

| Ophthalmic solution (Travatan™) | 0.004% ophthalmic solution of travoprost with 0.015% benzalkonim chloride as preservative | Travaprost (prodrug) | 2001 | Reduction of IOP |

| Ophthalmic solution (Xalatan™) | 0.005% ophthalmic solution of latanoprost with 0.02% benzalkonim chloride as preservative | Latanoprost (prodrug) | 1996 | Reduction of IOP |

| Ophthalmic solution (Propine™) | 0.1% ophthalmic solution of dipivefrin-HCl with benzalkonim chloride as preservative | Dipivefrin (prodrug) | 1980 | Control of IOP in chronic open-angle glaucoma |

| In situ gel-forming solution (Timoptic-XE™) | Sterile ophthalmic gel forming solution containing 0.25 or 0.5% of timolol equivalent timolol maleate, GELRITE gellan gum, tromethamine and mannitol, with 0.012% benzalkonim chloride as preservative | Timolol maleate | 1993 | Treatment of glaucoma |

| Ophthalmic solution (AzaSite™) | 1% sterile aqueous topical ophthalmic solution of azithromycin formulated in DuraSite® (polycarbophil, disodium EDTA, sodium chloride) with 0.003% benzalkonim chloride as preservative | Azithromycin | 2007 | Bacterial conjunctivitis |

| Ophthalmic gel (Zirgan™) | Sterile topical ophthalmic gel containing 0.15% of ganciclovir formulated with carbopol and 0.0075% benzalkonim chloride as preservative | Ganciclovir | 2009 | Herpetic keratatis |

| Ophthalmic emulsion (Durezol™) | Sterile topical aqueous ophthalmic emulsion containing 0.05% of difluprednate formulated with boric acid, castor oil, glycerin, and polysorbate 80, with 0.1% sorbic acid as preservative | Difluprednate | 2008 | Steroid for treatment of inflammation and pain associated with ocular surgery |

| Ophthalmic emulsion (Restasis™) | Sterile preservative free ophthalmic emulsion containing 0.05% of cyclosporine formulated with glycerin, castor oil, polysorbate-80 and carbomer1342. | Cyclosporine | 2002 | Increase tear production in dry eye diseases |

| Ophthalmic suspension (Betoptic-S™) | 0.25% ophthalmic suspension of betaxolol formulated with poly(styrene-divinyl benzene) sulfonic acid (Amberlite® IRP-69), Carbomer 934P, edetate disodium and 0.01% benzalkonim chloride as preservative | Betaxolol | 1990 | Treatment of glaucoma |

| Opthalmic inserts (Ocusert™) | Pilocarpine and alginic acid enclosed in thin ethylene-vinyl acetate membrane to control release of drug for 7 days | Pilocarpine | 1974 | Treatment of glaucoma |

| Intravitreal products | ||||

| Intravitreal implant (Ozurdex™) | Intravitreal implant containing 0.7 mg (700 μg) dexamethasone in the NOVADUR™ solid polymer drug delivery system | Dexamethasone | 2009 | Macular edema |

| Intra-vitreal implant (Retisert™) | Intravitreal implant containing 0.59 mg (590 μg) of flucinolone acetonide formulated with microcrystalline cellulose, polyvinyl alcohol and magnesium stearate | Flucinolone acetonide | 2005 | Chronic noninfectious uveitis |

| Intra-vitreal implant (Vitrasert™) | Intravitreal implant containing 4.5 mg of ganciclovir formulated in the nonbiodegradable polymers, polyvinyl alcohol and ethylene-vinyl acetate | Ganciclovir | 1996 | Cytomegalovirus retinitis |

EDTA: Disodium ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid; IOP: Intraocular pressure.

Key approaches to overcome short precorneal drug residence

Mucoadhesive & viscosity-enhancing polymers

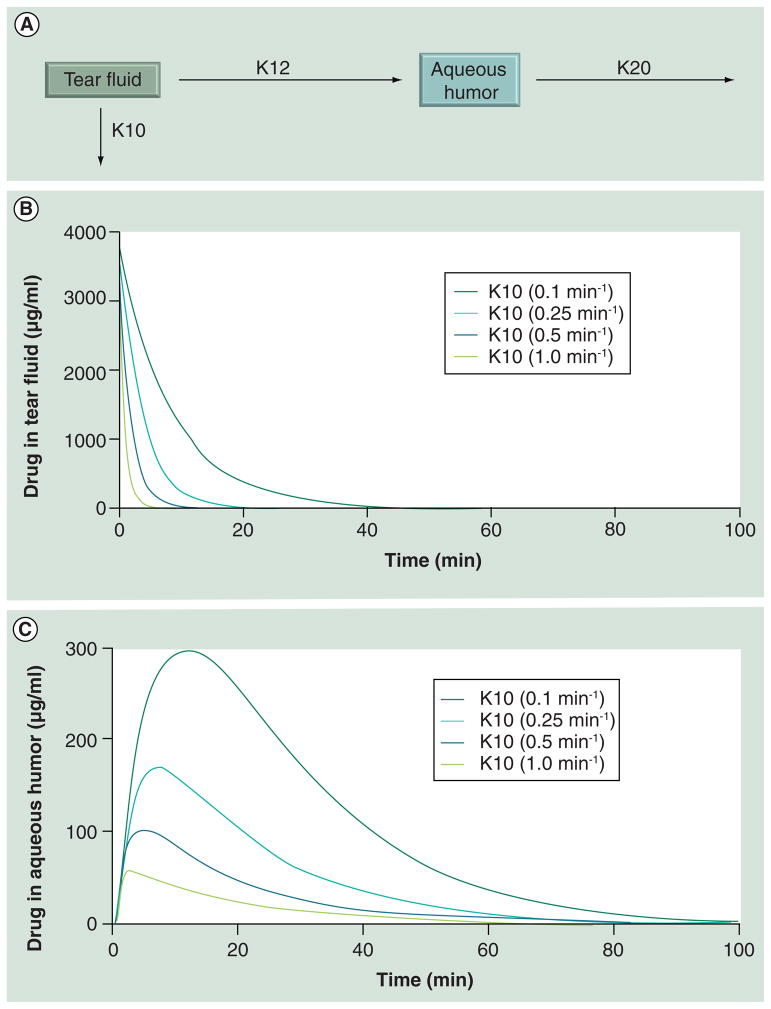

Topical formulations containing mucoadhesive or viscous materials can sustain and enhance drug delivery to target eye tissues. As shown in Table 2, several marketed topical formulations contain excipients that are capable of enhancing viscosity and/or allowing mucoadhesion. Examples of such excipients in ophthalmic formulations include gellan gum, polycarbophil, carbopol and poly(styrene-divinyl benzene) sulfonic acid. The viscosity of an ophthalmic formulation can range up to 20–30 cps [31]. Meseguer et al. reported that precorneal drainage of eye drops can be reduced in rabbit models by choosing vehicles containing various excipients, including hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC), xan-than gum and gellan gum (Gelerite®) [32]. These viscous and mucoadhesive vehicles reduced the elimination rate constant for pilocarpine by a maximum of approximately tenfold [32]. Based on this prior observation, we simulated the influence of reduced precorneal loss by a similar magnitude on drug levels in tear fluid as well as in the aqueous humor (Figure 2). The first order aqueous humor elimination rate constant chosen for the simulation was fixed at 0.06 min−1. This value is close to the 0.057 min−1 reported for the elimination of timolol from the aqueous humor in male Nippon albino rabbits [33]. From Figure 2, it is evident that a tenfold reduction in the precorneal loss rate constant sustains tear drug levels better, resulting in a 5.2-fold increase in the Cmax of the drug in the aqueous humor.

Figure 2. Choosing a mucoadhesive or viscous vehicle or carrier that reduces precorneal drug elimination can elevate tear fluid and aqueous humor drug levels.

(A) The simulation model for prediction of ocular pharmacokinetic after topical application. (B) Simulation of tear fluid concentration of a hypothetical drug at various precorneal elimination rates. A reduction in elimination rate is anticipated with viscous or mucoadhesive vehicles. (C) Simulation of aqueous humor concentration of a hypothetical drug at various precorneal elimination rates, when other parameters are kept constant. Prior to choosing such a system, any potential blurring of the vision by the viscous vehicle should be taken into consideration.

Formulations of azithromycin based on Durasite® [201] (polycarbophil USP – 90% polyacrylic acid cross-linked with 0.1–5% of divinyl glycol, ~1 × 106 Da, disodium ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid [EDTA], and sodium chloride) were recently shown to significantly enhance the ocular delivery of azithromycin in pigmented rabbits [34]. The AUC was 19.5-, 4.3-, and 2.8-fold higher in tears, cornea and aqueous humor, respectively, for the polycarbophil formulation when compared with the plain drug formulation. The mechanisms for enhanced drug delivery with polycarbophil can be twofold. First, this polymer is known to be a mucoadhesive agent in the eye. It was shown to reduce clearance from the eye surface in the rabbit model [32]. Second, evidence exists for the ability of polycarbophil to alter tight junctions, thereby elevating paracellular drug permeability [35]. While the elevations in AUCs observed in the azithromycin study are substantial, it is not clear whether such differences would translate to humans. A recent study reported that the topical delivery of besifloxacin (AUC0–24 [μg.h/g]) from an eye drop to the tear film follows the order: cynomolgus monkey (6440), pigmented rabbit (3240) and human (1263) [15].

Thus, viscous and/or mucoadhesive vehicles are useful in substantially enhancing topical drug delivery in animal models. However, it is unclear whether these benefits translate at the same level in humans with a blinking rate of 1000/h that is much higher than rabbits with a reported blinking rate of 3/h [36].

Contact lenses

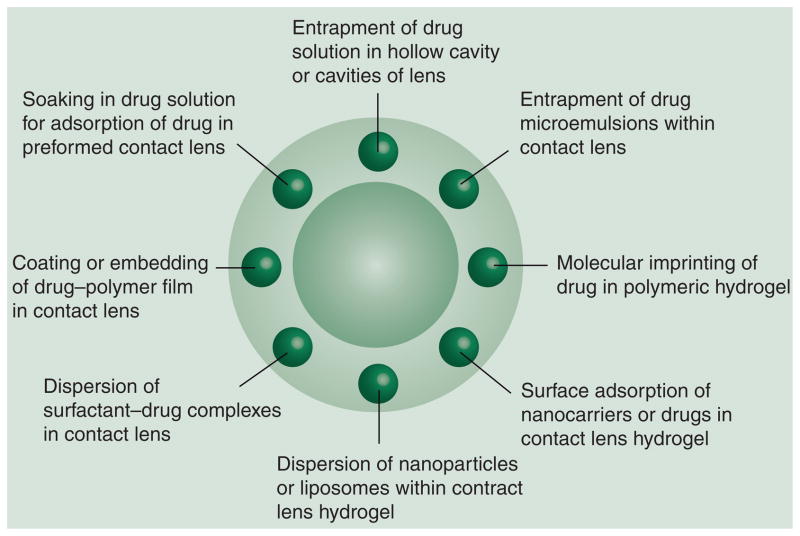

Contact lens-mediated drug delivery to the eye dates back to 1960 when Wichterle demonstrated the use of soft contact lenses for topical drug delivery [37]. In the intervening 50 years there have been no FDA-approved products based on this platform. However, recent research articles and patent activities suggest renewed enthusiasm for this approach in sustaining ocular drug delivery by the topical route. There are multiple challenges in developing contact lenses as ocular drug delivery systems. The current challenges are incorporation of sufficient amounts of the drug into the lens matrix, sustaining the drug release for the desired time frame at a controlled rate, good optical clarity, patient comfort during prolonged wear and biocompatibility. Prolonged wear of contact lens is associated with risk of infection such as microbial keratitis and dry eye syndrome [38]. Wearing of contact lenses is contraindicated in various inflammatory conditions of anterior segment such as anterior uveitis, vernal conjunctivitis, microbial keratitis and dry eye syndrome, limiting the applicability of this delivery system. Several ocular diseases are more prevalent in geriatric patients, who might find the use of contact lenses and contact lens based delivery systems inconvenient. Various methods have been used for loading the drug into lens delivery systems (Figure 3). Some key approaches to prepare contact lens based drug-delivery systems are discussed below.

Figure 3. Contact lenses for ocular drug delivery.

Drug molecules or delivery systems can be loaded in the periphery of contact lenses by several approaches including those illustrated.

Soaking of lenses in drug solution

The traditional method is to soak the preformed contact lens in drug solution so that the drug is adsorbed into the polymeric lenses. Such presoaked lenses allow limited, slow release of the drug into the post-lens lacrimal fluid. Soft contact lenses made from poly-hydroxymethacrylate (pHEMA) hydrogels release the majority of their drug content in one day [39,40]. New contact lenses made from silicone–hydrogel hybrid showed similar uptake but lower release of drug when compared with pHEMA lenses [41,42]. The ciprofloxacin uptake in pHEMA hydrogel lenses (Polymacon) and silicone hydrogel lenses (Balafilcon A) was similar at approximately 1800 μg. However, pHEMA lenses released 200 μg of ciprofloxacin in 24 h, while silicone hydrogel lenses released only 80 μg of drug in 24 h. Although soaking of preformed contact lenses in drug solution is an easy way to incorporate the drug, this approach suffers from various limitations including low drug loading and fast diffusion of the drug from the lenses. However, recently, Kim et al. showed that modified silicon hydrogel material is able to release timolol and dexamethasone at near zero order for 120 days, with very low burst release (<5%) on the first day [43]. To increase the drug loading in contact lenses, Nakada and Sugiyama developed contact lenses characterized by a hollow cavity that binds two lenses [202]. The compounded lens with the hollow cavity was soaked in a drug solution and allowed to release the drug into the eye upon insertion. Although this method showed more drug loading, it suffers from an additional disadvantage of low O2 and CO2 permeability. An alternative to contact lenses is the use of collagen shields soaked in drug solutions as a delivery system. Haugen et al. demonstrated that collagen shields presoaked in gatifloxacin achieve effects similar to multiple eye drops of gatifloxacin in relieving endophthalmitis in a rabbit model [44].

Molecularly imprinted polymeric hydrogels

Another approach that has received recent attention is to use molecularly imprinted polymeric hydrogels for contact lens-mediated ophthalmic drug delivery. The polymeric content of the lens is molded to recognize the structural features and bonding preferences of target drug molecules. Such an approach allows high drug affinity, selectivity and greater drug loading capacity. Hiratani et al. showed that the uptake of timolol in molecularly imprinted contact lens is 4.9-fold higher (2.51 ± 0.01 mM) than the nonimprinted gels (0.51 ± 0.07 mM) [45]. The overall binding affinity of timolol to molecularly imprinted gel is 12.3-times higher compared with non-imprinted gels [45]. The molecularly imprinted soft contact lenses for norfloxacin exhibited low drug loading for timolol (2 μmol/g) when compared with norfloxacin (8 μmol/g), even though timolol has a spatial size similar to nor-floxacin [46]. The difference in drug loading of imprinted hydrogel to norfloxacin and timolol is due to the specificity of the binding pocket in the imprinted gel used for preparing the contact lens [46]. Molecularly imprinted contact lenses exhibited a more prolonged drug release when compared with lenses soaked in drug solution. Molecularly imprinted contact lenses of ketotifen (diffusion coefficient: 5.57 ± 0.31 × 10 cm2/s) showed a diffusion coefficient that was nine-times lower than non-imprinted lenses (50.2 ± 4.8 × 10 cm2/s) [47]. For norfloxacin, non-imprinted contact lenses released almost all the drug content (>90%) within 12 h. On the other hand, norfloxacin-imprinted lenses released only 40% of the drug in 24 h with less than 10% burst release during the first 2 h [46].

Conjugation of nanoparticles or drug molecules to contact lens surface

Another approach to prepare contact lens drug delivery systems is to immobilize the drug or drug-loaded nanocarriers such as liposomes and nanoparticles on the surface of commercial soft contact lenses [48]. This can be achieved by surface functionalization of contact lenses to attach the drug or nanocarriers. Surface immobilization of levofloxacin liposomes on NeutrAvidin-coated Hioxifilcon-B contact lenses resulted in slower release than drug-soaked lenses. However, most of the drug (70%) was released within the first 5 h, with 30% remaining drug release occurring over the next 6 days [49]. Thus, the drawback of this approach is the relatively rapid detachment or disintegration of liposomes in the contact lenses. The lipid layer may also impede O2 and CO2 permeability.

Drug-polymer films integrated with contact lenses

Recent research from the Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary (Needham, MA, USA) demonstrated that near zero-order, 4-week release of ciprofloxacin and fluorescein is feasible from a drug-polymer film (poly[lactide-co-glycolide] [PLGA] 65:35) coated with a hydrogel (pHEMA) contact lens [50]. In vitro release studies showed that the drug release rate can be reduced by using high-molecular-weight polymers or increasing the polymer-to-drug ratios. Sano et al. showed that the delivery of levofloxacin to the aqueous humor in albino rabbits was 15-times greater at the end of 4 h with the piggyback contact lens delivery system when compared with eye drops dosed every 30 min interval over 4 h [51]. However, a comparison of drug levels at earlier time points was not provided. One of the major drawbacks of this approach is the increase in the thickness of the contact lens, which might result in low patient acceptance and poor permeability of O2 and CO2. However, the use of some new materials such as silicone hydrogel with higher O2 and CO2 permeability, in conjunction with drug-polymer films of reduced thickness may make this option more suitable for sustained ocular drug delivery.

Liposome-loaded contact lenses

Another novel approach is the entrapment of liposomes, nanoparticles, microemulsions and surfactant–drug complexes in contact lenses during manufacturing. In this method, drug-laden nanoparticles, liposomes or surfactant are added to the polymerizing medium of hydrogel matrix followed by polymerization to form contact lenses dispersed with drug carriers [52–54]. The overall drug release can be regulated by controlling the release of the drug from the various carriers, followed by the lens matrix to the post-lens tear film. Contact lenses created with dispersion of lidocaine-loaded liposomes or nano-particles showed nonlinear release of drug for 7 days, with an initial 15–20% burst release over the first few hours followed by near zero-order release for the remaining 7 days [53]. Kapoor et al. showed near zero-order release of cyclosporine in vitro from surfactant-laden hydrogel lenses, with the drug-release rate being 1.5% per day over 50 days [55].

Scleral lens delivery systems

Scleral gas-permeable rigid lenses are contact lenses initially developed by Boston Foundation for Sight, the contact lens service at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. They were developed in order to mask the abnormal corneal astigmatism when traditional rigid gas-permeable corneal contact lenses fail or contraindicated for the management of severe ocular surface diseases such as keratoconjunctivitis. The scleral lenses were first approved by the FDA in 1994 for the management of ectasia and irregular astigmatism. A scleral lens rests on the sclera and creates a space over the cornea and limbus, acting as a reservoir for tear fluid between the inner surface of the scleral lens and the cornea to form an expanded tear film. This expanded tear film over the cornea acts as a liquid bandage in corneal surface irregularities.

Rosenthal and Jacobs investigated the application of scleral lenses made from a gas-permeable polymer (Boston IV polymer, Itafluorfocon B) for ocular drug delivery [203]. The scleral lens allowed improved retention of topically applied drug on the corneal surface in the expanded tear film, that is, the tear film or artificially introduced tears retained between the corneal surface and the scleral lens. The drug may be added to the scleral lens, which acts as a reservoir for sustained release of the drug, or administered externally as an eye drop, which is retained in the expanded precorneal tear film. The topical delivery of Avastin for the treatment of corneal neovascularization using scleral lens delivery system showed promising results in a clinical study with five patients [56]. One drop of 1% bevacizumab solution free from preservatives and penetration enhancers was applied twice daily over 3 months to the eyes of patients fitted with Boston ocular surface prosthesis (BOSP) lens in the fluid reservoir of BOSP (a reservoir for expanded tear film formed between the inner surface of the scleral lens and the cornea filled with artificial tears). Drug effects were evident during the 30 days of treatment with marked regression of pannus and improvement of vision from finger count to 20/40 in one patient. Another patient, whose prior vision was 20/400, improved to 20/200 4 months after treatment initiation and at the end of 6 months had vision of 20/70. In all patients, the effects continued for the subsequent 60 days after cessation of dosing and no recurrence was noted. There were no ocular adverse effects such as breakdown of the corneal epithelial integrity with the scleral lens delivery system in humans. On the other hand, Kim et al. demonstrated breakdown of corneal epithelial integrity in the human eye after treatment with topical bevacizumab eye drops [57].

The above observation with Avastin and another recent report indicating the delivery of an anti-TNF-α-antibody fragment (ESBA105) to the anterior and posterior eye tissues following high-frequency dosing (three drops every hour over 10 h) and 30 s blink-free opening of the rabbit eye indicates that given sufficient duration of exposure, even macromolecules might permeate ocular barriers to access target tissues [58].

Punctal plug delivery systems

Punctal plugs have been used for more than 20 years for the symptomatic relief of dry eye syndrome. Punctal plugs occlude the nasolacrimal duct, thereby reducing tear drainage through the upper and/or lower punctum in the eye. Depending on the material used for punctal plug, the duration of occlusion ranges from 7 to 180 days [59,60]. Punctal plugs made from silicone [204], teflon, hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEM), polycaprolactone (PCL) or polydioxanone are intended for 180 day use, after which they need to be removed. On the other hand, punctal plugs made from animal collagen last for 7–10 days, during which time the plugs disintegrate [301]. Most punctal plugs are lost due to spontaneous extrusion from the puncta, and this risk is higher for plugs inserted in upper punctum compared with those inserted in lower punctum. Recently, punctal plugs made from thermosensitive, hydrophobic acrylic polymer were used to avoid extrusion problem (SmartPlug™, Medennium Inc.). This thermosensitive hydrophobic acrylic polymer is a solid rod at room temperature but becomes a soft cohesive gel when its temperature changes from room temperature to body temperature. Tuning of the material from a rigid rod into a gel-like plug conforms to the size and shape of the puncta, allowing retention of the plug.

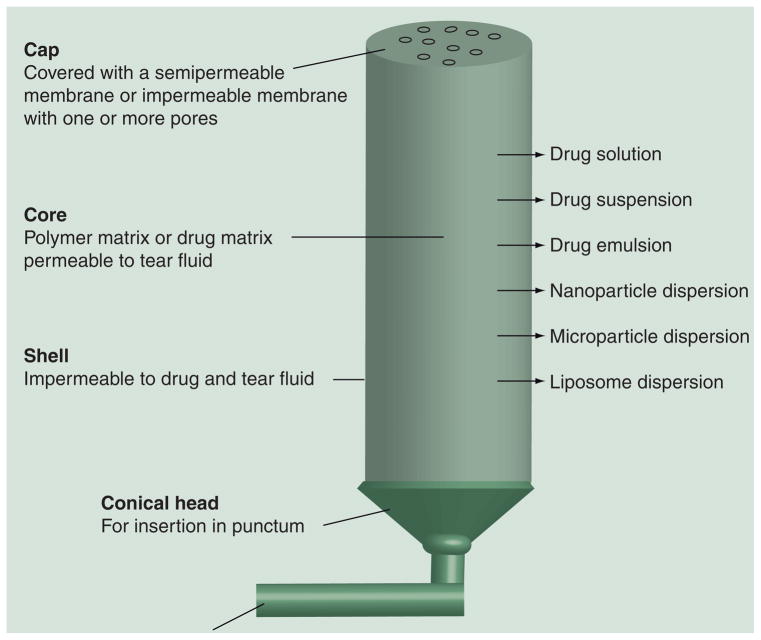

Use of punctal plugs for the delivery of ophthalmic medications offers a novel approach for chronic treatment of patients with various eye diseases including glaucoma and dry eye syndrome. Punctal plugs have several potential advantages over eye drops, including dose reduction (and hence minimization of systemic side effects), enhanced efficacy possibly due to controlled release of the drug at an optimum rate and better patient compliance with drug therapy. Punctal plugs used for drug delivery can be made from various polymers in a variety of shapes and sizes, with the final dimensions being limited by the punctum. The punctal plugs are mainly composed of a cylindrical body containing the drug compound, an optional outer shell made up of material impermeable to the drug and the tear fluid, an optional cap material containing pores and an optional unit to retain the punctal plug over prolonged periods of time. The bottom end is tapered and/or narrower in most punctal plugs to allow easy insertion into the punctum. The other end, otherwise known as the head portion, is exposed to the tear film and configured to rest on the exterior of punctum. The cap may have one or more pores extended throughout the body for release of the drug. In some designs, additional canalicular extension are configured to improve plug retention in the punctum and to serve as an additional reservoir for the therapeutic compound. Generally, a punctal plug drug delivery system is coated with a material that is impermeable to the drug and tear fluid on all sides except the head portion, through which the drug is released into the tear film. The release of the drug from a punctal plug is controlled by drug diffusion from the polymeric core to the tear fluid. The drug can be loaded in the central polymeric core as solution, suspension, microemulsions, nanoparticles, microparticles or liposomes with or without an additional polymer matrix. In some cases, punctal plugs are coated with a drug-containing polymeric matrix [204]. Alternatively, preformed plugs can be soaked in drug solution. However, these drug-loading approaches, when performed in the outer coat alone, result in limited drug loading. Most examples of punctal plugs showed near zero-order drug release rates for drug molecules [205,206]. For instance, cyclosporine-loaded punctal plugs made of HEMA core and coated with a silicone shell on all sides except the cylindrical head showed near zero-order release, with a release rate of approximately 3.0 μg/day over 45 days [206].

Punctal plug-mediated ocular delivery of latanoprost is in Phase II clinical study (QLT, Inc., BC, Canada). A Phase I study conducted in Mexico with five patients indicated safety and good tolerability and approximately 30% intraocular pressure (IOP) reduction over 3 months [302]. Current Phase II trials of latanoprost punctal plug delivery system (L-PPDS) are testing 44 and 81 μg doses in the United States. Preliminary results of ongoing Phase II trials with 44 μg L-PPDS showed a mean reduction in IOP by 3.5 mm Hg at the end of 4 weeks, with 36% of patients showing a decrease in IOP more than 5 mm Hg [302]. Out of the 60 patients enrolled, 48 patients (78%) completed the 4 week follow-up and retained L-PPDS in both eyes for 4 weeks. The L-PPDS was reasonably well tolerated over the testing period, with the overall adverse event incidence ranging from 1.7 to 11.7%. Commonly observed adverse effects included eye itchiness, eye irritation, increased lacrimation and ocular discomfort. Figure 4 summarizes the various possibilities for punctal plug designs in a single scheme.

Figure 4. Punctal plug delivery systems with various components and drug-loading methods.

The scheme captures a variety of technologies that are under development and is not intended to represent any one technology completely.

Key approaches to overcome permeability barriers

Several approaches, including prodrug derivatization, drug–cyclodextrin complexation, penetration enhancers and driving forces such as electrical currents or ultrasound, have been used to increase the permeability of drug molecules across the cornea. All these approaches except ultrasound have been shown to be beneficial in human studies, as described below.

Prodrugs

Prodrug derivatization can be used to enhance drug lipophilicity in order to overcome the permeability barrier. Examples of marketed prodrugs include dipivefrine, latanoprost, travoprost and bimatoprost. Dipivefrine, an ester prodrug of epinephrine, is 600-times more lipophilic and 17-fold more permeable across the cornea compared with epinephrine [61]. Ocular tissue distribution of dipivefrine and epinephrine in female New Zealand rabbits showed 15- and 11-times higher AUC(0-t) in cornea and aqueous humor, respectively, for the prodrug when compared with the parent molecule [61]. Dipivefrine comparative studies in humans showed that dipivefrine produces similar reduction in the IOP at 20-fold lower dose compared with epinephrine [62]. The prostaglandin analogs latanoprost, travoprost, bimatoprost are all prodrugs, with the former two being isopropyl ester prodrugs and the latter being an ethanolamine amide prodrug. These prodrugs increase drug lipophilicity and, hence, are expected to enhance drug absorption [63–66].

Alternatively, for a drug with dissolution rate-limited absorption, prodrugs can be used to enhance drug solubility and, therefore, the driving force to encourage passive drug absorption. Cyclosporine A (CsA) is a potent immuno-suppressive drug that is of therapeutic value in treating various ocular disease including dry eye syndrome, uveitis and corneal graft rejection [67]. Poor aqueous solubility of CsA is a limiting factor in the development of topical ocular formulations [67,68]. An emulsion formulation of CsA (Restasis®) is currently being marketed for dry eye syndrome. However, blurred vision has been reported with this emulsion formulation [69,70]. The vehicles for such emulsions should be chosen with care since some oily vehicles can enhance corneal permeability of fluorescein by sevenfold in human eyes [71]. UNIL088 is a hydrophilic ester prodrug of CsA with 25,000-times higher solubility than CsA in isotonic phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.0) [67]. Eye drops of this CsA prodrug are effective in treating corneal graft rejection in rats [72].

Currently, prodrugs to enhance transporter mediated drug absorption are being investigated for enhanced ocular drug delivery [73]. Evidence exists for the presence of organic anion, organic cation and peptide transporters in various ocular barriers including cornea, conjunctiva, and blood–retinal barriers [74–76]. In addition, evidence exists for efflux transporters such as P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRPs) in the ocular barriers [47,77–80]. Delivery of an anionic aldose reductase inhibitor to cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells [13], as well as neural retina in vivo in a rat model [13], was elevated by probenecid treatment. This may be an outcome of drug efflux inhibition from eye tissues by probenecid.

Functionalized nanoparticles

One approach to enhance the epithelial uptake and transport of poorly permeable drugs is to employ nanoparticle formulations that allow superior cellular delivery. For instance, using a bovine ex vivo, intact eye model, Kompella et al. demonstrated that corneal epithelial uptake of 20-nm nanoparticles can be elevated from approximately 2–16% by surface coating or functionalizing nanoparticles [81]. The nano-particles did not perturb the tight junctional architecture or paracellular permeability of the cornea. Furthermore, the uptake of transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles could be reduced by excess free transferrin ligand. In this study, an elevation in particle uptake was observed as early as 5 min following eye drop instillation. Thus, functionalized nanoparticles allow rapid, receptor-mediated uptake of particles into epithelial cells of the eye.

Drug cyclodextrin complexes

Drug–cyclodextrin complexation is a useful way to increase the aqueous solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs without changing their molecular properties [82]. A key advantage of cyclodextrins over conventional membrane-perturbing penetration enhancers such as benzalkonium chloride (BAK) and EDTA, is that they increase ocular drug bioavailability predominantly by increasing drug solubility [83]. Various clinical and preclinical studies demonstrated the efficiency of this approach in increasing the ocular bioavailability of poorly water soluble drug molecules such as hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, cyclosporine, and acetazoloa-mide [84–87]. A clinical study of 0.32% dexamethasone-cyclodextrin-polymer complexes in humans showed 2.6-times higher AUC in the aqueous humor when compared with a dexamethasone suspension [88]. Interestingly, several eye drop products containing cyclodextrins are currently marketed in Europe. Examples include Voltaren® (diclofenac-Na with hydroxyl propyl-β-cyclodextrin [HPβCD]), Indocid® (indomethacin with HPβCD) and Clorocil® (chloramphenicol with methyl β-cyclodextrin [MβCD]). It is anticipated that ophthalmic products containing cyclodextrins may enter the US market in the near future.

In addition to the use of cyclodextrins, drug solubility can also be enhanced by including suitable salt forms of the drug, surfactants or co-solvents.

Penetration enhancers

Despite extensive research in the area of penetration enhancers to overcome epithelial barriers, no clinical ophthalmic formulation relies directly on the penetration-enhancing properties of its excipients. However, the fact that several ophthalmic formulations contain benzalkonium chloride and/or EDTA as preservatives is noteworthy. Both these excipients are well known to alter biological membranes, thereby enhancing drug permeability [89–91]. For a comprehensive review on the mechanisms of action of penetration enhancers, the readers are referred to an article by Lee et al. [92].

Iontophoresis

For charged drug molecules or vehicles, iontophoresis is a viable approach for enhanced drug delivery. Iontophoresis utilizes low currents to enhance the penetration of charged molecules across tissue barriers. The drug is applied using an electrode carrying the same charge as the drug. An electrode with the opposite charge placed elsewhere in the body completes the circuit. The ionized drug molecule penetrates the tissue by electric repulsion. Additionally, neutral molecules can potentially be delivered using iontophoresis on the basis of electro-osmosis or solute-associated fluid transport.

Eljarrat-Binstock and Domb prepared a comprehensive review on the application of iontophoresis for ocular drug delivery [93]. This noninvasive method can deliver drug molecules to both anterior and posterior segments of the eye. Several preclinical studies demonstrated the potential of iontophoresis in delivering antibiotics, antifungals, steroids and NSAIDs to both anterior and posterior segments using transcorneal and trans-scleral iontophoresis, respectively. Several investigators conducted clinical studies using iontophoresis [94–98]. The EyeGate® II system, designed for transcorneal drug delivery, consists of an ocular applicator, syringe, adaptor for transferring the drug product from reservoirs to the applicator and generator to provide consistent current to the electrode. FDA-granted orphan drug designation for the delivery of dexamethasone phosphate using the EyeGate-II system for corneal graft rejection therapy. Iontophoresis may prove an attractive option to patients who are not responsive to eye drop therapy. In addition, Phase II clinical trials are ongoing for the evaluation of safety and efficacy of EGP-437 (combination of the above drug and device) to treat uveitis and dry eye syndrome. Ocuphor (Iomed Inc., USA) and Visulex (Aciont Inc., USA) are the other ocular iontophoresis systems under investigation for trans-scleral iontophoresis. Harwath-Winter et al. demonstrated the superiority of ocular iontophoresis for the delivery of sodium iodide in treating dry eye syndrome in 28 patients [99]. The investigators observed no corneal edema or epithelial damage in this study. Parkinson et al. reported severe burning sensation and discomfort in two out of six patients at a current dose of 4 mA over 2 min during an ocular iontophoresis study [100]. Thus, one limitation of ocular iontophoresis is potential discomfort to patients. Another limitation of ocular iontophoresis is inadequate sustained delivery. Given the chronic nature of eye disorders, such as diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, glaucoma and uveitis, iontophoresis is required at a high frequency. The safety of prolonged iontophoretic drug delivery has yet to be established.

Invasive approaches for drug delivery to the back of the eye

Trans-scleral drug delivery

In order to enhance drug delivery to the back of the eye, drug can be administered adjacent to the sclera by various periocular routes including subconjunctival, sub-Tenon, peribulbar and retrobulbar routes [27]. Ayalasomayajula and Kompella showed that posterior subconjunctival injection enhances celecoxib delivery to the retina by 54-fold compared with a systemic injection [11]. Since this route of administration is invasive, albeit less invasive to the globe than intravitreal injections, dosing at a low frequency is desirable. That is, sustained release dosage forms are required. This can be achieved by administering drug suspensions, in situ-forming drug suspensions, drug–polymer particles or implants, preferably those that allow unidirectional drug permeability towards sclera. Using a single periocular injection of slow-release polymeric microparticles of celecoxib, Amrite et al. demonstrated that drug levels as well as effects can be sustained for at least 2 months in a diabetic rat model [9,101]. Sclera is more permeable to drug molecules when compared with cornea and conjunctiva [102]. Kim et al. showed that the delivery of high-molecular-weight dextran–dye conjugate (70 kDa) to choroid and retina after subconjunctival injection in mice [103]. However, the choroid-Bruch’s membrane can bind lipophilic drugs, hindering their transport [104]. For lipophilic molecules, drug partitioning or binding in tissue is significantly higher in choroid-RPE when compared with the retina. High, nonproductive binding to choroid-RPE minimizes drug entry into the retina during trans-scleral drug delivery [105]. The RPE, a tight monolayer of epithelial cells underlying choroid, is an additional barrier for drug delivery to the neural retina. Thus, although periocular administration improves drug delivery by overcoming the conjunctival permeability barrier, there are additional barriers that need to be overcome in facilitating retinal drug delivery. Table 3 summarizes some of the sustained trans-scleral drug delivery approaches assessed to date.

Table 3.

Sustained trans-scleral drug delivery for treating retinal disorders.

| Drug | Delivery system | Route of injection | Duration of observation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovalbumin | Thermosetting gel | Subconjunctival injection | Drug levels were detected in choroid-retina for 14 days | [121] |

| Celecoxib | PLGA microparticles | Subconjunctival injection for posterior segment delivery | Drug levels were detected in retina, vitreous, lens and cornea for 14 days Significant reduction of diabetic retinopathy related changes at 14 days |

[10] |

| Tetramethyl rhodamine-dextran | Solution | Subconjunctival injection | Drug levels were detected in sclera, choroid and retina for 70 h | [122] |

| Budesonide | PLA microparticles | Subconjunctival injection for posterior segment delivery | Drug levels were detected in retina, vitreous, and cornea for 14 days | [123] |

| Budesonide | PLA nanoparticles | Subconjunctival injection for posterior segment delivery | Drug levels were detected in retina, vitreous and cornea for 7 days | [123] |

| Celecoxib | PLGA microparticles | Subconjunctival injection for posterior segment delivery | Drug levels were detected in sclera-choroid, retina, vitreous and cornea after 2 months of injection Significant reduction of diabetic retinopathy-related changes after 2 months |

[9] |

| Carboplatin | PAMAM dendrimeric nanoparticles | Subconjunctival injection for posterior segment delivery | Significant reduction in retinal tumor burden after 21 days | [124] |

| 5-flurouracil | PLGA microspheres | Subconjunctival injection for anterior and posterior segment delivery | Drug levels were detected in aqueous humor, and sclera for 7 days | [125] |

| Carboplatin | Fibrin sealant | Subconjunctival injection for posterior segment delivery | Effect was observed for 21 days | [126] |

| PKC412 | PLGA microspheres | Periocular injection for posterior segment delivery | Drug levels were detected in vitreous, retina and choroid after 20 days Marked reduction in choroidal neovascularization area after 20 days |

[127] |

| PEDF protein | Protein solution | Subconjunctival injection for posterior segment delivery | Drug levels were detected in sclera and retina for 24 h | [85] |

PAMAM: Poly(amido amine); PEDF: Pigment epithelium-derived factor; PLA: Poly(lactic acid); PLGA: Poly(lactide-co-glycolide).

Intravitreal injections

Intravitreal injection of drug solution or suspension is the most efficacious method for targeted delivery of drug molecules to tissues of the posterior segment of eye. Drugs in solution disappear rapidly form the vitreous humor, requiring frequent injections to maintain therapeutic levels [106]. By contrast, drug suspensions prolong drug residence in the vitreous by allowing slow dissolution of the drug in the vitreous [106]. Durairaj et al. demonstrated that the elimination half-life for diclofenac acid suspension was 24 and 18 days in vitreous and choroid-retina, respectively, when compared with 2.9 and 0.9 h observed with diclofenac sodium solution after intravitreal injection in New Zealand white rabbits [107]. Intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide suspension is used in clinical settings for the treatments of wet ARMD and diabetic macular edema [108,109]. The duration of drug effect depends on the dose administered and the pathological condition. In nonvitrectomized human eyes, the duration of the effect after single intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide suspension was approximately 6–9 and 2–4 months for 20- and 4-mg doses, respectively [110]. Single intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide suspension (4 mg) showed drug levels in vitreous up to 3 months in nonvitrectomized human eyes [111]. The elimination half-life from vitreous is twofold higher in vitrectomized eyes when compared with the nonvitrectomized eyes [112].

Intravitreal implants

Implants are biodegradable or nondegradable solid dosage forms typically made of polymers that slowly release the drug of interest over prolonged periods [113,114]. Depending on the biodegradation nature of the polymer used, implants are classified as nonbiodegradable and biodegradable implants. Drug release can be controlled more precisely using nondegradable implants. Due to changes in the properties of the system with polymer degradation, control of drug release from degradable systems is more difficult. While degradable systems offer the advantage of physiological clearance of all system components over time, nondegradable systems remain permanently in the body unless surgically removed. Currently, Vitrasert, Retisert and Ozurdex are three implants approved for intravitreal administration. Whilst the former two are nondegradable implants, the latter is degradable. Intravitreal implants are either sutured in the pars plana area or injected into the vitreous humor. Implants have many potential advantages over traditional delivery systems including drug delivery closer to the target tissue in the posterior segment, dose reduction due to localized delivery (and hence minimization of systemic side effects)and reduced complications including infections due to low frequency dosing [115]. This results in reduced dosing frequency and enhanced efficacy possibly due to controlled release of the drug at an optimum rate. Although implants are currently approved for treating diseases of the posterior segment of the eye, they can potentially be used for treating diseases of the anterior segment as well. Subconjunctival and intrascleral implants may deliver greater quantities of the drug to the anterior segment, whereas suprachoroidal and intravitreal implants might deliver greater quantities of the drug to the posterior segment. Additionally, evidence exists for the usefulness of subcutaneously administered biodegradable implants in sustaining the retinal delivery and efficacy of an aldose-reductase inhibitor in treating diabetic retinopathy [14].

Vitrasert was the first nonbiodegradable intra-vitreal implants approved by the FDA in 1996 for the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis. Vitrasert is a reservoir implant device consisting of a drug pellet of ganciclovir coated with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a permeable polymer that regulates drug diffusion and ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA). EVA is an impermeable polymer that controls the area through which a drug is released [116]. This device needs surgical implantation in the pars plana region and also requires surgical removal once the drug is depleted. This device exhibits no burst release and sustains the drug release for 5–8 months after administration. However, the device is associated with risk of endopthalmitis and retinal detachment.

Retisert is another nonbiodegradable implant of flucinolone acetonide approved in 2005 for the treatment of chronic noninfectious uveitis. This implant contains 0.59 mg of drug coated with PVA and silicone laminates and provides sustained drug delivery over a period of 3 years. It delivers approximately 0.5 μg of drug/day at a constant rate. Retisert has shown significant efficacy but results in side effects, including cataracts and elevated IOP, which are associated with several corticosteroids such as fluocinolone acetonide [116]. Medidur/Iluvien is another nonbiodegradable implant of flucinolone acetonide that is undergoing Phase III clinical trials for the treatment of diabetic macular edema. Fluocinolone acetonide inhibits secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor, a pathological implicated in vascular leakage and neovascularization associated with diabetic retinopathy [117]. Medidur or Ileuvien is much smaller in size (3.0 mm long and 0.37 mm in diameter) and can be injected intravitreally using a 25 G needle [118]. Thus, surgical procedures are being obviated with the development of miniaturized, injectable nondegradable implants. Given the small size of these implants, and the already compromised state of eyes with back-of-the-eye disorders, these implants are not expected to cause any major vision disturbances due to their mere presence.

As an alternative to nondegradable systems, biodegradable implants, such as Ozurdex and Surodex, are being investigated for dexamethasone delivery. Dexamethasone, a corticosteroid similar to fluocinolone acetonide, is expected to alleviate vascular complications. Ozurdex is an intravitreal implant containing 0.7 mg of dexametahsone and was approved by the FDA in 2009 for the treatment of macular edema. Surodex is an anterior segment implant of dexamethasone for treating postoperative inflammation after cataract surgery. Biodegradable implants are typically made of degradable polymers such as PLGA, which are degraded in the body into water and CO2. Therefore, these implants disappear with time and require no surgical removal. The release rate of the drug from biodegradable implants can be controlled by altering the ratios of lactide and glycolide in the polymers. Unlike nondegradable systems, zero-order release is difficult to achieve with degradable systems. Similar to nondegradable implants of corticosteroids, degradable systems also suffer from side effects including cataracts and elevated IOP. Intravitreal implants are revolutionizing the therapy of back-of-the-eye disorders by allowing effective drug delivery over prolonged periods. To reduce the side effects of corticosteroid implants, more efforts are required in proper dose selection and placement [119] of the devices in the vitreous cavity.

Challenges & future perspectives

The incidence of age-related chronic ocular diseases such as glaucoma, cataract, macular and other retinal degenerative disorders is expected to rise dramatically in the next two decades. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop novel ocular delivery systems that meet the multimedication needs of the elderly with pre-existing visual and motor impairment. The ideal ocular delivery system is one that is easy to manufacture, allows noninvasive self-administration, achieves and maintains effective drug concentrations at the target site for desired time intervals, minimizes systemic exposure and affords good patient comfort, acceptance and compliance. While eye drops may be ideal for treating anterior segment eye diseases, it may not be the most reliable drug delivery vehicle entrusted with targeted drug delivery to the posterior segment. By contrast, other systems discussed elsewhere in this article, such as implants, are less than ideal, they will remain the ‘best’ there is for the time being. Clearly, more innovative measures are needed to achieve breakthroughs in topical ocular drug delivery. These measures will be discussed in turn.

Noninvasive topical drug delivery to the back of the eye

Currently there is no product approved for treating disorders associated with the back of the eye utilizing noninvasive topical drug administration. Some potential approaches to enhance drug delivery to the back of the eye include delivery systems that allow prolonged precorneal retention, such as contact lens-type devices and mucoadhesive delivery systems. In addition, prodrugs targeting transporters present in conjunctiva and underlying barriers might be a viable option for enhanced drug delivery to the back of the eye using eye drops. Similarly, functionalized nanoparticles targeting the ocular surface and underlying barriers are potential options to allow noninvasive drug delivery to the back of the eye. Iontophoresis also allows enhanced drug delivery to the back of the eye from ocular surface.

Sustained drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye

Although sustained drug delivery to the back of the eye is now feasible for up to 3 years with injectable or surgically placed intravitreal implants, sustained drug delivery to the tissues of the anterior segment of the eye for several days or longer periods is not feasible with any of the topical ophthalmic preparations that are currently available. The key challenge to overcome is short precorneal residence time. While contact lens-delivery systems are likely to sustain drug delivery for a week or several weeks, punctal plug delivery systems will likely allow sustained drug delivery for a few months. Implantable systems such as Surodex, although suitable for anterior segment delivery following placement in the anterior chamber, widespread patient acceptance of such visible systems has yet to be established.

Membrane & dynamic barriers to drug permeability

Cornea, conjunctiva, choroid layer and RPE are some of the barriers that a topically applied drug has to cross prior to reaching target tissues in the anterior or posterior segments of the eye. In addition, the drug has to overcome vascular clearance mechanisms in the conjunctiva, episclera and choroid during membrane transport prior to reaching the tissues of the back of the eye. It appears that if sufficient duration of drug contact is allowed on the eye surface, several of these barriers can be crossed to a significant extent even by macromolecules. Alternative approaches to overcoming membrane barriers are to design prodrugs targeted to transporters or design nanoparticles capable of crossing barriers efficiently.

Side effects associated with intravitreal implants

It is well known that intravitreal procedures can potentially cause retinal detachment and endophthalmitis, particularly when repeated. Thus, there has been a need for sustained drug delivery for several years since diseases such as diabetic retinopathy and ARMD require several years of drug therapy. While sustained delivery for approximately 3 years is currently feasible for fluocinolone acetonide, a small lipophilic molecule, such systems have yet to be developed for small or large hydrophilic drugs. In the future, it is anticipated that significant efforts will be made in this direction with innovative polymers and delivery systems. In addition, even at low dose delivery, corticosteroids in the vitreous humor result in cataracts and elevated IOP. To minimize these side effects, improved localization of the implant near the target site, further reduction in dose and pulsatile steroid delivery are some of the potential future options.

It is encouraging to see that several new approaches for sustained and enhanced topical drug delivery, notably punctal plugs, scleral lenses and iontophoresis, are in clinical trial (Table 4). With such innovation, significant advances are anticipated in drug delivery from the precorneal area similar to those achieved with novel delivery systems administered in the intravitreal space. In addition to the technical challenges discussed in this article, several regulatory and toxicology issues must also be considered in developing a safe and effective drug product for the eye. The reader is referred to an excellent review by Novack addressing these topics [120].

Table 4.

Some novel ophthalmic drug delivery methods that are under clinical development.

| Delivery system | Drug | Indication | Developmental stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iontophoresis | Dexamethasone phosphate | Dry eye syndrome, uveitis and corneal graft rejection | Clinical trials |

| Punctal plug | Latanoprost | Ocular hypertension and open angle glaucoma | Phase II clinical trial |

| Scleral lenses | Avastin | Corneal neovascularization | Clinical study |

Key term

- Iontophoresis

Use of electrical current to deliver drug molecules across barrier tissues

- Contact lens delivery system

Drug-loaded contact lenses placed on the corneal surface

- Scleral lens delivery system

Contact lens-like delivery system that allows scleral contact of a drug-loaded reservoir

- Punctal plug delivery system

Drug-containing plug-like delivery systems placed in the nasolacrimal duct

- Functionalized nanoparticles

Drug-loaded nanoparticles coated on the surface with a ligand for cell surface receptors

- Trans-scleral drug delivery

Drug delivery across sclera and underlying barriers to treat disorders of the back of the eye

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact reprints@future-science.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was supported, in part, by NIH grants EY018940 and EY017533. Uday Kompella is a consultant for Allergan, Genentech and Vistakon. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

- 1.Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Zhang X, Honeycutt AA, Lesesne SB, Saaddine J. Forecasting age-related macular degeneration through the year 2050: the potential impact of new treatments. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(4):533–540. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowak JZ. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD): pathogenesis and therapy. Pharmacol Rep. 2006;58(3):353–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VisionGain. Visiongain Reports. 2010. World ophthalmic pharmaceutical market 2010–2025. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheruvu NP, Amrite AC, Kompella UB. Effect of diabetes on trans-scleral delivery of celecoxib. Pharm Res. 2009;26(2):404–414. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amrite AC, Edelhauser HF, Singh SR, Kompella UB. Effect of circulation on the disposition and ocular tissue distribution of 20 nm nanoparticles after periocular administration. Mol Vis. 2008;14:150–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheruvu NP, Amrite AC, Kompella UB. Effect of eye pigmentation on trans-scleral drug delivery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(1):333–341. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amrite AC, Edelhauser HF, Kompella UB. Modeling of corneal and retinal pharmacokinetics after periocular drug administration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(1):320–332. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kador PF, Randazzo J, Babb T, et al. Topical aldose reductase inhibitor formulations for effective lens drug delivery in a rat model for sugar cataracts. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23(2):116–123. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amrite AC, Ayalasomayajula SP, Cheruvu NP, Kompella UB. Single periocular injection of celecoxib-PLGA microparticles inhibits diabetes-induced elevations in retinal PGE2, VEGF, and vascular leakage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(3):1149–1160. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayalasomayajula SP, Kompella UB. Subconjunctivally administered celecoxib-PLGA microparticles sustain retinal drug levels and alleviate diabetes-induced oxidative stress in a rat model. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;511(2–3):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayalasomayajula SP, Kompella UB. Retinal delivery of celecoxib is several-fold higher following subconjunctival administration compared with systemic administration. Pharm Res. 2004;21(10):1797–1804. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000045231.51924.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koushik K, Kompella UB. Preparation of large porous deslorelin-plga microparticles with reduced residual solvent and cellular uptake using a supercritical carbon dioxide process. Pharm Res. 2004;21(3):524–535. doi: 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000019308.25479.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sunkara G, Ayalasomayajula SP, Rao CS, Vennerstrom JL, Deruiter J, Kompella UB. Systemic and ocular pharmacokinetics of N-4-benzoylaminophenylsulfonylglycine (BAPSG), a novel aldose reductase inhibitor. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004;56(3):351–358. doi: 10.1211/0022357022908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aukunuru JV, Sunkara G, Ayalasomayajula SP, Deruiter J, Clark RC, Kompella UB. A biodegradable injectable implant sustains systemic and ocular delivery of an aldose reductase inhibitor and ameliorates biochemical changes in a galactose-fed rat model for diabetic complications. Pharm Res. 2002;19(3):278–285. doi: 10.1023/a:1014438800893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proksch JW, Granvil CP, Siou-Mermet R, Comstock TL, Paterno MR, Ward KW. Ocular pharmacokinetics of besifloxacin following topical administration to rabbits, monkeys, and humans. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2009;25(4):335–344. doi: 10.1089/jop.2008.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee VH, Robinson JR. Topical ocular drug delivery: recent developments and future challenges. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1986;2(1):67–108. doi: 10.1089/jop.1986.2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macha S, Mitra AK. Ocular pharmacokinetics in rabbits using a novel dual probe microdialysis technique. Exp Eye Res. 2001;72(3):289–299. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macha S, Duvvuri S, Mitra AK. Ocular disposition of novel lipophilic diester prodrugs of ganciclovir following intravitreal administration using microdialysis. Curr Eye Res. 2004;28(2):77–84. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.28.2.77.26233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dias CS, Mitra AK. Posterior segment ocular pharmacokinetics using microdialysis in a conscious rabbit model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(1):300–305. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]