Tdrd5-deficient mice develop a functional haploid genome despite spermiogenesis arrest at the round spermatid stage.

Abstract

The Tudor domain–containing proteins (TDRDs) are an evolutionarily conserved family of proteins involved in germ cell development. We show here that in mice, TDRD5 is a novel component of the intermitochondrial cements (IMCs) and the chromatoid bodies (CBs), which are cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein granules involved in RNA processing for spermatogenesis. Tdrd5-deficient males are sterile because of spermiogenic arrest at the round spermatid stage, with occasional failure in meiotic prophase. Without TDRD5, IMCs and CBs are disorganized, with mislocalization of their key components, including TDRD1/6/7/9 and MIWI/MILI/MIWI2. In addition, Tdrd5-deficient germ cells fail to repress LINE-1 retrotransposons with DNA-demethylated promoters. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element modulator (CREM) and TRF2, key transcription factors for spermiogenesis, are expressed in Tdrd5-deficient round spermatids, but their targets, including Prm1/Prm2/Tnp1, are severely down-regulated, which indicates the importance of IMC/CB-mediated regulation for postmeiotic gene expression. Strikingly, Tdrd5-deficient round spermatids injected into oocytes contribute to fertile offspring, demonstrating that acquisition of a functional haploid genome may be uncoupled from TDRD5 function.

Introduction

Germ cell development is a complex process that culminates in the production of haploid gametes, i.e., spermatozoa in males and oocytes in females, which in turn unite to form a totipotent zygote that ensures embryogenesis. In the mouse, the germ cell lineage in a newly developing embryo arises as primordial germ cells (PGCs) that segregate from somatic lineages and establish at around embryonic day 7.0 (E7.0) in the posterior extraembryonic mesoderm (Saitou and Yamaji, 2010). They proliferate, migrate through the hindgut endoderm, and colonize the embryonic gonads at ∼E10.5 (Richardson and Lehmann, 2010). In both males and females, PGCs continue to proliferate until ∼E13.5 (McLaren, 2003). Under the influence of signals from gonadal somatic cells, the germ cells thereafter undergo sexually dimorphic development: in males, they enter into mitotic G0/G1 arrest (prospermatogonia), remain quiescent until a few days after birth, and subsequently initiate a robust process of spermatogenesis (Phillips et al., 2010; Yoshida, 2010), whereas in females, they enter into the prophase I of meiosis and become arrested at the diplotene stage, preparing for maturation as oocytes (Edson et al., 2009; Bowles and Koopman, 2010).

The Tudor domain-containing proteins (TDRDs) are a subclass of the evolutionarily conserved Tud family of proteins and play key roles in germ cell development (Siomi et al., 2010). The founder member of the Tud family is Drosophila melanogaster Tudor, which functions in assembly of the polar granules and in germ cell specification (Boswell and Mahowald, 1985; Arkov et al., 2006). The Tudor domain by itself serves as a binding module for methylated arginine or lysine residues (Maurer-Stroh et al., 2003). There exist 26 Tud family proteins in the mouse, of which 10 are TDRDs (Fig. 1 A), and some of them have been shown to be critical regulators of spermatogenesis (Chuma et al., 2006; Shoji et al., 2009; Vasileva et al., 2009). Importantly, TDRDs form a distinct complex with P element–induced wimpy testis (PIWIs), a germline-specific subfamily of the evolutionarily conserved Argonaute proteins with small noncoding RNA-binding activities, through their symmetric dimethylated arginine (sDMA), which is likely to be catalyzed by protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5; Reuter et al., 2009; Vagin et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009). The murine PIWI subfamily members consist of mouse homologue of PIWI, PIWIL1 (MIWI), PIWIL2 (MILI), and PIWIL24 (MIWI2), and associate specifically with PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) of ∼24–30 nucleotides in length, most of which are derived from repetitive intergenic DNA elements including transposon sequences (for review see Siomi et al., 2010).

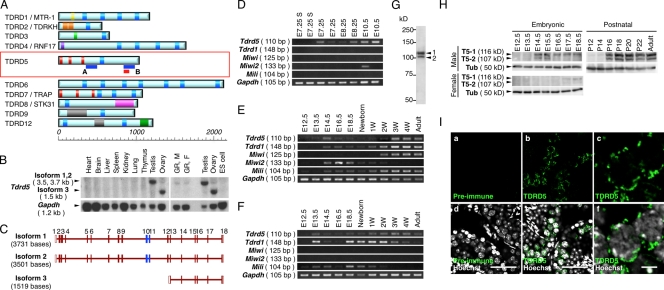

Figure 1.

Tdrd5 shows specific expression in the germ cell lineage. (A) The structures of TDRD proteins. The scale indicates the length in amino acids. The blue bars in A and B represent the positions of the probes for Northern blot in B and in Fig. 3 C. The red box indicates the position of the peptide used for antibody production. Blue rectangles, Tudor domain; yellow, myeloid-nervy-DEAF-1 (MYND) domain; light orange, K homology RNA-binding domain type I (KH-I) domain; pale green, UBA-like domain; dark purple, Zinc finger, RING-type domain; dark orange, LOTUS domain; magenta, Ser/Thr protein kinase-like domain; gray, DNA/RNA helicase domain; dark green, CS-like domain. (B) Northern blot for Tdrd5 expression. GR, E13.5 genital ridges; M, Male; F, Female. (C) Exon–intron structures of Tdrd5 isoforms. Open boxes represent untranslated regions and closed brown boxes represent coding exons. Blue boxes represent exons encoding the Tudor domain. (D–F) Expression of the indicated genes in single-cell cDNAs of E7.25, E8.25, and E10.5 PGCs, and E7.25 somatic neighbors (E7.25S; D); and in embryonic, newborn, juvenile (W, week after birth), and adult (8-wk-old) testes (E) and ovaries (F). (G and H) Western blots for TDRD5 in the adult testis (8 wk old; G), in embryonic testes and ovaries, and in postnatal testes (H). T5-1 and -2, TDRD5 isoforms 1 and 2; Tub, αTubulin. (I) Immunofluorescence analysis of TDRD5 in adult testis sections. Shown are sections stained by the preimmune serum (a) or the purified anti-TDRD5 antibody (b and c), with merged images with Hoechst (d–f). c and f show magnified images of parts of b and e, respectively. Bars: (d and e), 50 µm; (f), 5 µm.

Recent studies have shown that in prospermatogonia, TDRD1 forms a complex with MILI and localizes at the intermitochondrial cements (IMCs; or pi-bodies), whereas TDRD9 associates with MIWI2 and colocalizes with MAELSTROM (Soper et al., 2008), and forms discrete compartments called piP-bodies with typical components of the processing bodies (P-bodies), which are structures involved in either storage or degradation of nontranslating mRNAs (Aravin et al., 2009; Shoji et al., 2009). Accordingly, the TDRD1–MILI and TDRD9–MIWI2(–MAEL) complexes function cooperatively in “the amplification loop pathway” of primary and secondary piRNA biogenesis, respectively, and these complexes with their respective piRNAs not only act to process retrotransposon-derived transcripts, but also elicit the silencing of cognate transposon sequences by their DNA remethylation (Aravin et al., 2009; Shoji et al., 2009). The mechanism by which transposon sequences are targeted for DNA methylation is unknown. Mutations in Mili, Miwi2, and Mael lead to de-repression of transposable elements, including long interspersed repetitive element 1 (LINE-1) and intracisternal A particles (IAP), whereas mutations in Tdrd1 and Tdrd9 result in preferential loss of silencing of LINE-1 (Carmell et al., 2007; Aravin et al., 2008; Kuramochi-Miyagawa et al., 2008; Soper et al., 2008; Reuter et al., 2009; Shoji et al., 2009). All these mutations are associated with impaired piRNA biogenesis. As a consequence of aberrant transposon activation, all these mutations lead to meiotic failure at the zygotene or pachytene stages (Kuramochi-Miyagawa et al., 2004, 2008; Carmell et al., 2007; Aravin et al., 2008; Soper et al., 2008; Reuter et al., 2009; Shoji et al., 2009).

In contrast, TDRD4/RNF17, TDRD6, and MIWI play key roles in the regulation of spermiogenesis (Deng and Lin, 2002; Pan et al., 2005; Vasileva et al., 2009). In the mutants for Tdrd4/Rnf17, Tdrd6, and Miwi, spermatocytes appear to undergo normal meiotic divisions and form round spermatids, but they essentially fail to develop into elongated spermatids (Deng and Lin, 2002; Pan et al., 2005; Vasileva et al., 2009). The phenotype of these mutants is similar to that of the mutant for cAMP response element modulator (CREM), a master transcriptional regulator for spermiogenic gene expression (Blendy et al., 1996; Nantel et al., 1996). TDRD6 begins to be expressed in the spermatocytes at the pachytene stage, continues to be expressed in the round spermatids, and localizes at the IMCs and the chromatoid bodies (CBs; Hosokawa et al., 2007; Vasileva et al., 2009), whereas TDRD4/RNF17 is expressed and diffusely localized in the cytoplasm of all male germ cells (spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatids; Pan et al., 2005). Interestingly, TDRD4/RNF17 additionally forms unique cytoplasmic granules distinct from the IMCs and the CBs (Pan et al., 2005). MIWI expression starts from the pachytene spermatocytes and continues in the round spermatids, with localization at the cytoplasm of spermatocytes and at the CB of round spermatids (Deng and Lin, 2002). TDRD6 is required for CB assembly and miRNA regulation (Vasileva et al., 2009), whereas TDRD4/RNF17 regulates genes critical for spermiogenesis, including Act, Prm1, Prm2, and Tnp1, but not Miwi, Crem, Trf2, and Tpap (Pan et al., 2005). MIWI appears to regulate a diverse range of pathways, including the biogenesis of a specific subset of piRNAs and miRNAs as well as the control of expression for Act, which encodes a testis-specific CREM coactivator, and for CREM target genes (Deng and Lin, 2002; Grivna et al., 2006a,b).

We identified Tdrd5 as a gene specifically expressed in PGCs as early as E7.25 by a single-cell cDNA microarray analysis (Kurimoto et al., 2008). It has been shown previously that Tdrd5 mRNA is expressed specifically in male germ cells after E11.5 and continues to be expressed in adult testes (Smith et al., 2004), but the function of TDRD5 remains unexplored. We describe here the precise expression, subcellular localization, and critical function of TDRD5 in germ cell development in mice.

Results

Expression of TDRD5 in the germ cell lineage

Tdrd5 has been reported to encode a 1,039–amino acid protein with a single Tudor domain in its center and three potential double-stranded RNA-binding motifs at its N terminus (Fig. 1 A; Smith et al., 2004; Anantharaman et al., 2010; Callebaut and Mornon, 2010; Patil and Kai, 2010). Northern blot analysis showed that Tdrd5 is expressed in the testis and ovary as well as in the genital ridges at E13.5 in both sexes (Fig. 1 B). PCR with multiple primer pairs and sequence analyses of the amplified products identified the presence of three types of Tdrd5 transcripts: isoform 1 with a putative full length of 3,117 bases in the coding region, isoform 2 lacking 231 bases of exon 3 presumably because of an alternative splicing, and isoform 3 encoding only the C-terminal half expressed in the ovary (Fig. 1, B and C).

We examined the expression of Tdrd5 in germ cell development by RT-PCR. Tdrd5 was detected as early as E7.25 in PGCs and was seen at all the subsequent stages, with its expression being low after E18.5 up to 2 wk after birth (Fig. 1, D–F). In contrast, Tdrd1 was first detected at around E13.5–E14.5 and appeared to be abundantly present in the ovary (Fig. 1, D–F). Miwi was seen specifically in the postnatal testes and Miwi2 was detected from E10.5 up to 3 wk after birth only in males (Fig. 1, D–F). Mili was detected after E12.5 throughout the germ cell development in males as well as until 2–3 wk after birth in females (Fig. 1, D–F). These findings are consistent with previous studies (Kuramochi-Miyagawa et al., 2001; Chuma et al., 2003; Kurimoto et al., 2008) and reveal the differential expression of Tdrd5 among the Tdrd and Piwi families.

Western blot analysis of the adult testis lysate using an anti-TDRD5 antibody identified two specific bands with molecular mass of ∼120 and ∼105 kD, which corresponds well with the protein sizes from the isoforms 1 (116 kD) and 2 (107 kD), respectively (Fig. 1, C and G). TDRD5 was detected as early as ∼E13.5 in embryonic testes, but its expression declined around the perinatal period and then was restored at ∼2 wk after birth (Fig. 1 H). We detected TDRD5 in the embryonic ovary at a low level (Fig. 1 H). Immunohistochemical staining of adult testis sections revealed that TDRD5 is mainly expressed in the spermatocytes from the pachytene stage onward and is localized in a granular fashion around the perinuclear area in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1 I).

TDRD5 localizes at IMCs and CBs

To analyze the subcellular localization of TDRD5 more precisely, we established transgenic lines expressing TDRD5 fused with EGFP at its C terminus from the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC; Fig. 2 A). The transgenic lines precisely recapitulated the Tdrd5 expression (Fig. S1, A and B) and TDRD5 localization (Fig. 2 B): TDRD5-EGFP showed perinuclear granular distribution in the pachytene spermatocytes and was localized at a single spot in the round spermatids in the stage I seminiferous tubules (Fig. 2 C). Because the transgene rescued the phenotype of Tdrd5 knockout mice (see the following section and Fig. S1 C), we conclude that TDRD-EGFP reflects the functional expression and localization of TDRD5.

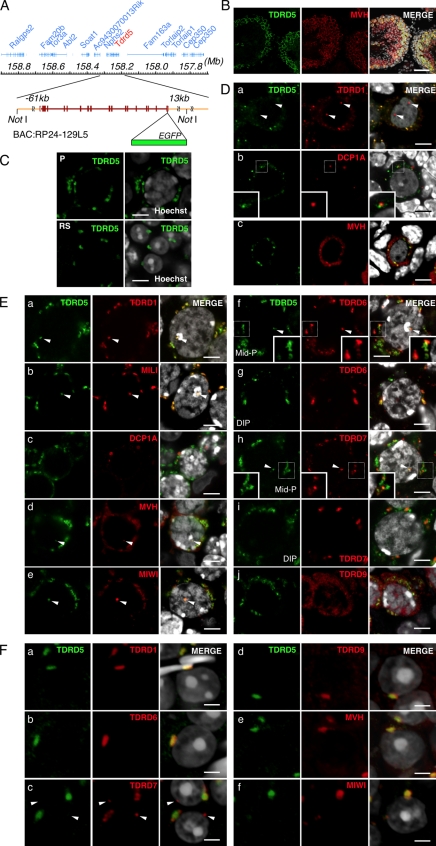

Figure 2.

TDRD5 localizes at IMCs and CBs in male germ cells. (A) The BAC bearing Tdrd5 and surrounding genes. EGFP was recombined in front of the stop codon of Tdrd5. (B) TDRD5-EGFP in an adult testis section costained with MVH and DAPI. The right shows merged images with Hoechst (from B to F). (C) TDRD5-EGFP in a pachytene spermatocyte (P) and round spermatids (RS). (D) Localization of TDRD5-EGFP (green) costained with TDRD1 (a), DCP1A (b), and MVH (c; red) in prospermatogonia at E17.5. Arrowheads in a indicate the nuclear localization of TDRD1. Insets in b show magnified views of the boxed regions. (E) Localization of TDRD5-EGFP (green) costained with TDRD1 (a), MILI (b), DCP1A (c), MVH (d), MIWI (e), TDRD6 (f), TDRD7 (h), and TDRD9 (j; red) in pachytene spermatocytes or with TDRD6 (g) and TDRD7 (I; red) in diplotene spermatocytes. Arrowheads indicate TDRD5-positive nuclear foci. Insets in f and h show magnified views of the boxed regions. (F) Localization of TDRD5-EGFP (green) costained with TDRD1 (a), TDRD6 (b), TDRD7 (c), TDRD9 (d), MVH (e), and MIWI (f; red) in round spermatids in the stage I seminiferous tubules. Arrowheads in c indicate the lone TDRD7-positive spot. Bars: (B) 50 µm; (C, D, and E) 5 µm; (F) 3 µm.

We compared the localization of TDRD5-EGFP with that of other TDRD proteins and relevant factors in male germ cells. In fetal prospermatogonia, TDRD5-EGFP showed a clear dotted perinuclear distribution, which colocalized with TDRD1 (Fig. 2 D). Unlike TDRD1, TDRD5 was not present in the nucleus (Fig. 2 D). TDRD5 did not colocalize with DCP1A (Fig. 2 D, b), a marker for the P-body, although in some places, TDRD5-positive foci were located in close proximity to DCP1A-positive ones. TDRD5-positive foci were also positive for mouse vasa homologue (MVH), but MVH showed a wider distribution throughout the cytoplasm. Thus, TDRD5 is a component of the IMCs and hence the pi-bodies but not the piP-bodies in prospermatogonia.

In spermatocytes at the pachytene stage, TDRD5 colocalized with TDRD1 and with MILI but not with DCP1A, and TDRD5-positive foci were positive for MVH, but MVH showed a wider distribution. This indicates that TDRD5 continues to localize at IMCs or CBs at this stage (Fig. 2 E, a–d). TDRD5 showed almost complete colocalization with MIWI (Fig. 2 E, e). In mid-pachytene spermatocytes, TDRD5 exhibited some colocalization with TDRD6 and -7, but in some areas, their distributions were different (Fig. 2 E, f and h). In diplotene spermatocytes, TDRD5 became mostly colocalized with TDRD6 but not with TDRD7 (Fig. 2 E, g and i). Notably, we consistently observed a single TDRD5-positive spot in the nucleus (Fig. 2 E, a, b, d, and e, arrowheads). This spot was also positive for TDRD1, MILI, MVH, MIWI, TDRD6, and TDRD7 (Fig. 2 E, f and h), and was located adjacent to DAPI-positive heterochromatin and CREST-positive centromeres (Fig. S2). Further examination revealed that these Tudor/Piwi-containing nuclear bodies (T/PNBs) are frequently observed in mid-to-late pachytene spermatocytes, and are enriched with proteins bearing sDMA, including histone H2/H4 with sDMA at Arg3 (H2/H4R3me2s), but are distinct from B23-positive nucleoli (Fig. S2).

With respect to round spermatids, TDRD5-EGFP is detectable only in those in the stage I seminiferous tubules, and is colocalized with MVH, MIWI, and TDRD1, -6, and -9 at large single spots, i.e., at the CBs (Fig. 2 F, a, b, d, e, and f). Interestingly, TDRD7 exhibited a distinct localization: it localized at peripheral areas of TDRD5-EGFP–positive CBs and at other isolated spots (Fig. 2 F, c). Collectively, these results indicate that TDRD5 is a novel component of the IMCs and CBs, and that TDRDs exhibit finely organized and distinct subcellular distribution, which suggests their functional diversity.

Tdrd5-deficient males are sterile because of spermatogenic failure

To determine the function of Tdrd5, we knocked out Tdrd5 by deleting the exons 10 and 11 encoding the Tudor domain by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells (ESCs; Fig. 3 A). A potential splicing fusing exon 9 with exon 12 results in a frame-shift mutation, creating a nonfunctional protein. We isolated three ESCs that underwent homologous recombination (Fig. 3 B) and generated chimeric mice by two independent clones, and both lines showed the germline transmission. The Tdrd5 heterozygously targeted+/− mice appeared to be normal, and we crossed the heterozygotes to obtain Tdrd5 homozygously targeted−/− mice.

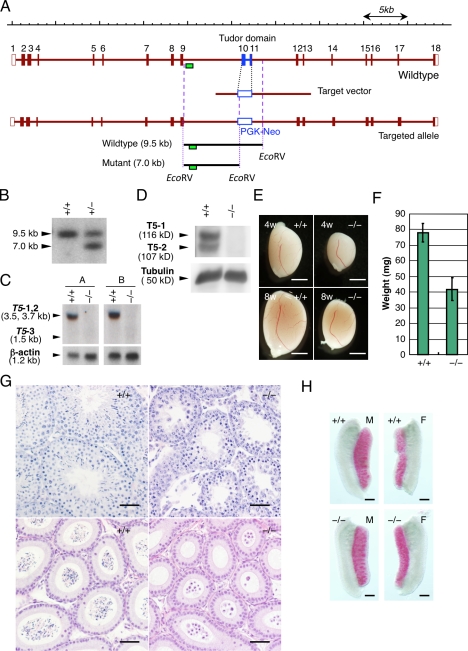

Figure 3.

Tdrd5 knockout leads to male sterility. (A) The gene-targeting strategy for Tdrd5. The correct targeting generates ∼7.0-kb bands when digested with EcoRV and probed with the 5′ probe (green boxes). (B) Southern blot for the detection of the gene targeting. (C and D) Northern (C) or Western (D) blots of Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− testes for Tdrd5 or TDRD5 expression. (C) A, probe A (5′); B, probe B (3′) as shown in Fig. 1 A. T5-1, -2, and -3, Tdrd5 isoforms 1, 2, and 3. (E) Testes of Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− mice of 4- and 8-wk of age. (F) The weight (the averages with SD; error bars) of Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− testes (8 wk old). (G) Histology of Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− testes (top) and epididymis (bottom) stained by hematoxylin and eosin. (H) Alkaline phosphatase staining of Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− male (left) and female (right) gonads at E12.5. Bars: (E) 2 mm; (G) 50 µm; (H) 300 µm.

The Tdrd5−/− mice were born in accordance with the Mendelian ratio (+/+:+/−:−/− = 78:170:87), and they appeared grossly normal. However, we found that Tdrd5−/− males were sterile, whereas Tdrd5−/− females were fertile with normal litter sizes (unpublished data). The testes of Tdrd5−/− males lacked Tdrd5 mRNA as determined using both 5′ and 3′ probes (Figs. 1 A and 3 C), and were devoid of TDRD5 protein (Fig. 3 D), which indicates that the targeted allele is a null allele. The Tdrd5−/− testes were significantly smaller (nearly 50% lower weight) than those of their wild-type littermates as early as 4 wk old (Fig. 3, E and F). The seminiferous tubules of the Tdrd5−/− adult testes were thinner than those of the wild types, and although they appeared to contain spermatogonia and spermatocytes, they contained no elongating spermatids (Fig. 3 G). In the epididymal ducts, although there existed plenty of transported spermatozoa in the wild types, there were no such cells but some abnormal round spermatid-like cells or larger degenerating cells in the Tdrd5−/− mutants (Fig. 3 G). In the embryonic testes and ovaries at E12.5, there appeared to be a normal number of alkaline phosphatase–positive PGCs in Tdrd5−/− mutants (Fig. 3 H). These findings demonstrate that Tdrd5 is dispensable for PGC specification and development but is essential for spermatogenesis. Because we observed identical phenotypes in two independent knockout lines and in their intercrosses (unpublished data), we describe the analysis of one line maintained by the intercrosses hereafter.

Critical function of TDRD5 for spermiogenesis

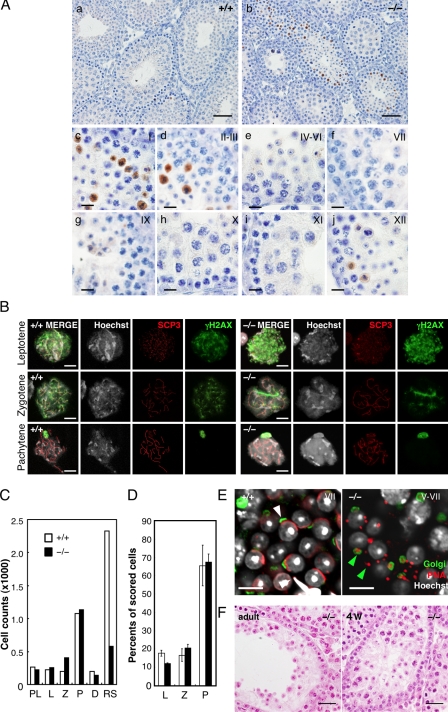

We examined whether aberrant apoptosis occurs in Tdrd5−/− mutant testes. The Tdrd5-deficient seminiferous tubules exhibited a higher level of apoptotic cell death than the wild-type tubules (Fig. 4 A). The apoptotic signals came specifically from cells located inside of the stage XII and I–III tubules (Fig. 4 A, c–j). These cells were considered to be either the secondary spermatocytes or the round spermatids at steps 1–3.

Figure 4.

Spermiogenic defects in Tdrd5−/− testes. (A) Apoptosis in Tdrd5−/− testes. Tdrd5+/+ (a) and Tdrd5−/− (b) testes stained with anti-activated Caspase3 antibody (brown) counterstained with hematoxylin. Magnified images of Tdrd5−/− seminiferous tubules at stages I (c), II and III (d), IV–VI (e), VII (f), IX (g), X (h), XI (i), and XII (j) are shown. (B) Nuclear-spread analysis of the meiotic prophase in Tdrd5+/+ (left) and Tdrd5−/− (right) testes. Meiotic spermatocytes were staged (leptotene, zygotene, and pachytene) based on the nuclear morphology (Hoechst) and the distribution pattern of SCP3 and γH2AX. The bright spots detected by γH2AX in the pachytene spermatocytes are XY bodies. (C) Total counts of the indicated cells from hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of Tdrd5+/+ (white) and Tdrd5−/− (black) testes. PL, preleptotene; L, leptotene ; Z, zygotene; P, pachytene; D, diplotene spermatocytes; RS, round spermatids. (D) Percentage (the average with SD; error bars) of the indicated cells in the surface spreads of Tdrd5+/+ (white) and Tdrd5−/− (black) testes. (E) Acrosome visualized by PNA (red) and Golgi58K (green) staining of Tdrd5+/+ (left, white arrowhead, stage V) and Tdrd5−/− (right, green arrowheads, stage V–VII) round spermatids, counter-stained with Hoechst (white). (F) Histology of a Tdrd5−/− seminiferous tubule (left, adult; right, 4 wk old) with a severe phenotype stained by hematoxylin and eosin. Bars: (A, a and b) 50 µm; (A, c–j) 10 µm; (B and E) 10 µm; (F) 20 µm.

To confirm this finding, we made single-cell spreads of testicular cells from wild-type and Tdrd5−/− mice, and measured the number of spermatocytes at different stages of meiosis and of round spermatids. The progression of the prophase of meiosis I as determined by the synaptonemal complex assembly appeared not to be significantly impaired in Tdrd5−/− mutants, and the numbers or the ratio of the cells at the preleptotene, leptotene, zygotene, pachytene, and diplotene stages were not altered between the wild types and Tdrd5−/− mutants (Fig. 4, B–D). The numbers of the round spermatids, however, were much smaller in Tdrd5−/− mutants (Fig. 4 C). Moreover, the remaining round spermatids in Tdrd5−/− mutants failed to organize proper acrosomes (Fig. 4 E): the peanut agglutinin (PNA)-positive acrosomal vesicles failed to enlarge and flatten, and were abnormally delineated by the Golgi apparatus, which indicates that the round spermatids in Tdrd5−/− mutants are arrested at steps 2–4.

Despite the apparently normal progression of the first meiotic prophase in most of the seminiferous tubules, we occasionally observed tubules with earlier defects: in some tubules of the Tdrd5−/− testes, the numbers of pachytene spermatocytes were smaller and no spermatids were observed (Fig. 4 F). Similar defects were also observed sporadically in Tdrd5−/− testes undergoing the first-round spermatogenesis at 4 wk (Fig. 4 F). Collectively, these findings indicate that TDRD5 may not be absolutely essential for the progression of the prophase of meiosis I (although its absence impacts the meiosis at a low frequency), but that it is indispensable for proper spermiogenesis, playing a critical function in the both formation and maturation of the round spermatids.

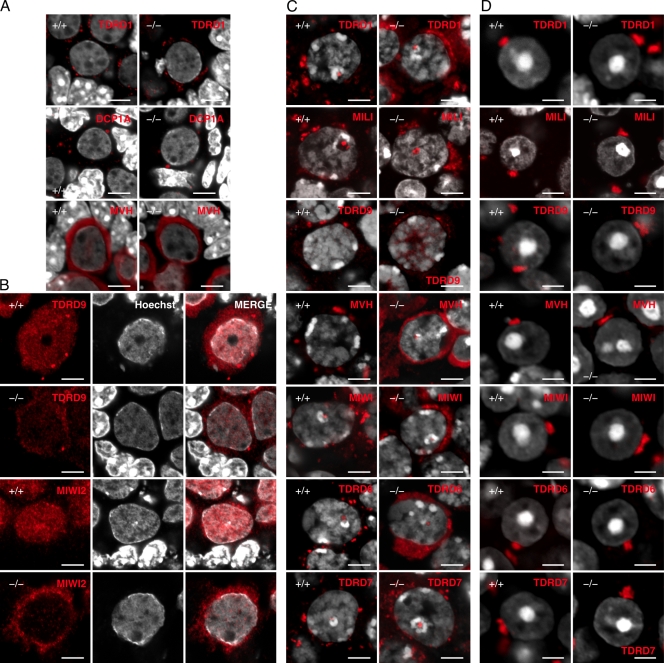

TDRD5 is essential for IMC and CB assembly

Because TDRD5 is localized at the IMCs and CBs with other components, we examined the localization of relevant factors in Tdrd5−/− mutants. In fetal prospermatogonia, there appeared to be minimal, if any, impact of TDRD5 deficiency on the TDRD1-positive foci (IMCs, pi-bodies; Fig. 5 A). Notably, however, TDRD9, which was localized throughout the nucleus as well as at several cytoplasmic foci (piP-bodies) in wild-type cells (Figs. 2 D and 5B), was largely (but not completely) excluded from the nucleus and more concentrated in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5 B). This was also the case for the localization of MIWI2 at E17.5 and postnatal day 2 (P2; Fig. 5 B and Fig. S3). In mid-to-late pachytene spermatocytes of Tdrd5−/− mutants, TDRDs, MVH, and MIWI all distributed more diffusely compared with their localization in wild-type cells (Fig. 5 C). Additionally, we noted a more frequent occurrence of T/PNBs in Tdrd5−/− mutants than in wild-type cells (Fig. S2). In round spermatids, TDRDs, MVH, and MIWI all appeared to localize at a single area in both the wild types and Tdrd5−/− mutants (Fig. 5 D).

Figure 5.

Impaired subcellular localization of TDRDs and relevant factors in Tdrd5−/− male germ cells. (A) Subcellular localization of TDRD1, DCP1A, and MVH (red) in Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− prospermatogonia (E17.5) counterstained with Hoechst (white). (B) Subcellular localization of TDRD9 and MIWI2 (red) in Tdrd5+/+ (top and third row) and Tdrd5−/− (second and bottom rows) prospermatogonia (E17.5) counterstained with Hoechst (white). (C and D) Subcellular localization of TDRD1, MILI, TDRD9, MVH, MIWI, TDRD6, and TDRD7 (red) in Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− pachytene spermatocytes (C) or round spermatids (D) counterstained with Hoechst (white). Bars: (A–C) 5 µm; (D) 3 µm.

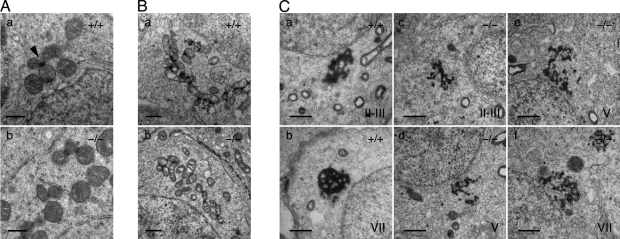

We next analyzed the IMCs and CBs in Tdrd5 mutants by electron microscopy. In wild-type adult spermatogonia, clustered mitochondria appeared around the nuclei, and some electron-dense materials corresponding to the IMCs were observed between mitochondria (Fig. 6 A, a, arrowhead; Eddy, 1975; Chuma et al., 2009). In Tdrd5−/− mutants, similar structures appeared but they looked less eminent (Fig. 6 A, b). In the wild-type pachytene spermatocytes, the IMCs developed extensively, but in Tdrd5−/− mutants, these structures had less electron density, and were poorly organized and fewer in number (Fig. 6 B, a and b). Strikingly, in contrast to the highly organized and compact CBs in wild-type round spermatids, those in Tdrd5−/− mutants looked disorganized and fragmented, and were smaller in seminiferous tubules from stage II–VII (Fig. 6 C, a–f), despite the fact that TDRDs, MVH, and MIWI appeared to be clustered relatively normally at the resolution of the immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5 D). This suggests that TDRDs, MVH, and MIWI are organized abnormally in Tdrd5−/− round spermatids. These findings demonstrate that TDRD5 has a critical function in the appropriate assembly of the IMC and CB complexes.

Figure 6.

Underdeveloped IMCs and CBs in Tdrd5−/− germ cells. Electron micrographs of the IMCs (A and B) and the CBs (C) in fetal prospermatogonia (A), pachytene spermatocytes (B), and round spermatids (C) of Tdrd5+/+ (A, a; B, a; and C, a and b) and Tdrd5−/− (A, b; B, b; and C, c–f) mice. An arrowhead in A indicates the IMC. Stages of the seminiferous tubules are shown in C. Bars; (A) 0.5 µm; (B and C) 1 µm.

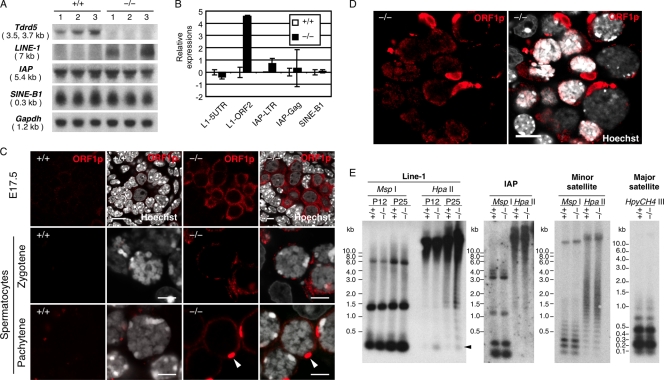

De-repression of LINE-1 retrotransposons in Tdrd5−/− mutants

We next examined the expression of retrotransposons in Tdrd5−/− mutants. As shown in Fig. 7 A, at P14, LINE-1 mRNA was elevated in two out of three Tdrd5−/− testes. In contrast, other retrotransposons such as IAP or short interspersed nonrepetitive elements B1 (SINE-B1) were expressed at similar levels between wild-type and mutant animals. Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) analysis indicated that the open reading frame (ORF) 2 of LINE-1 showed ∼20-times higher expression in Tdrd5−/− mutants (Fig. 7 B). We immunostained the Tdrd5−/− mutant as well as wild-type testes for the ORF1 coding protein of LINE-1 (ORF1p; Martin and Branciforte, 1993; Goodier and Kazazian, 2008). In prospermatogonia, ORF1p was strongly detected in the cytoplasm of Tdrd5−/− mutants but not that of the wild types (Fig. 7 C and Fig. S3). ORF1p was also up-regulated in the cytoplasm of spermatocytes at the zygotene and pachytene stages in Tdrd5−/− mutants, with a characteristic accumulation in a single spot (Fig. 7 C). Although we did not detect nuclear accumulation of ORF1p in most of the tubules with proper meiotic progression, we observed stronger accumulation of ORF1p in the cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus of spermatocytes in tubules with apparent defects in meiotic prophase (Fig. 7 D).

Figure 7.

Abnormal activation of LINE-1 in Tdrd5−/− germ cells. (A) Northern blot of retrotransposon (LINE-1, IAP, SINE-B1) expression in Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− testes at P14. (B) Q-PCR analysis of retrotransposon expression in Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− testes at P14 shown by the log2 scale (the average with SD; error bars). The expression levels in Tdrd5+/+ animals are set as zero. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of ORF1p in prospermatogonia (E17.5) and zygotene and pachytene spermatocytes in Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− mice. Arrowheads indicate ORF1p-strong-positive spots. Bars, 5 µm. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of ORF1p at a severely damaged locus of a Tdrd5−/− testis. Bar, 10 µm. (E) Methylation-sensitive Southern blot analysis of DNA methylation of LINE-1 (at P12 and P25) and IAP (at P25) promoters, and minor and major satellite sequences (at P25) in Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− mice.

To examine whether LINE-1 regulation is linked with the DNA demethylation of the LINE-1 promoter elements, we analyzed the DNA methylation of LINE-1 as well as other repetitive elements by methylation-sensitive Southern blotting. The Tdrd5−/− mutants exhibited weak but clearly detectable DNA demethylation of the LINE-1 promoter elements both at P14 and P25, but not of other repetitive sequences such as IAP and minor and major satellites (Fig. 7 E). Collectively, these data indicate that LINE-1 retrotransposons are up-regulated in Tdrd5−/− mutants by the failure to remethylate their promoter elements during the critical period of DNA remethylation in male germ cells (Kato et al., 2007; Schaefer et al., 2007; Sasaki and Matsui, 2008). Presumably, the degree of the deregulation of LINE-1 is milder in Tdrd5−/− mutants when compared with those in Tdrd1, Tdrd9, Mael, Mili, and Miwi2 mutants because in contrast to these mutants, most, but not all, Tdrd5−/− mutant germ cells manage to go through the meiotic prophase.

Impaired spermiogenic gene expression in round spermatids of Tdrd5−/− mutants

To gain insight into the mechanism of spermiogenic failure in Tdrd5 mutants, we examined the expression of key genes involved in spermiogenesis in Tdrd5 mutants. We first looked at the expression of relevant genes by Q-PCR in testes during the first-round spermatogenesis at P15, P20, and P25 (Fig. 8 A). At P15, some of the proliferating spermatogonia go into the first-round spermatogenesis and reach the pachytene stage. At P20, many of the germ cells are still in the meiotic prophase, but some finish meiosis and a few round spermatids just begin to appear. At P25, round spermatids appear in most seminiferous tubules and a few elongated spermatids begin to be formed (Fig. S4; Bellvé et al., 1977; Zhang et al., 2001; Deng and Lin, 2002).

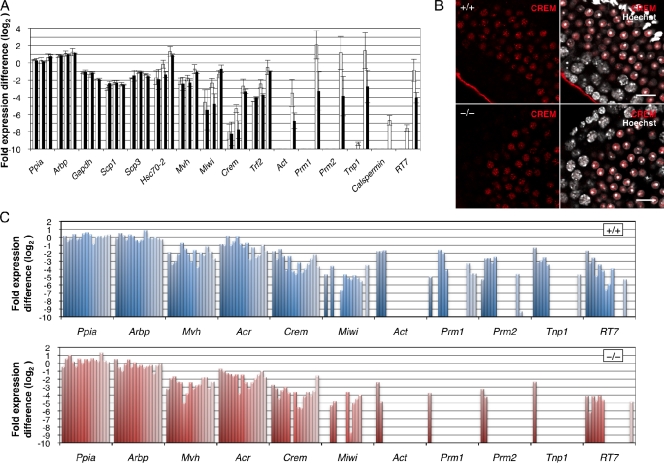

Figure 8.

Impaired gene expression in Tdrd5−/− round spermatids. (A) Q-PCR analysis of the expression of pre- and postmeiotic genes during the first-round spermatogenesis (P15, P20, and P25) in Tdrd5+/+ (white) and Tdrd5−/− (black) mice was normalized by the mean of Gapdh, Ppia, and Arbp, and shown as the fold expression difference from the average in the log2 scale with the SD (error bars). The left, middle, and right paired columns show the values at P15, P20, and P25, respectively. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of CREM expression (red) in the Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− testes counterstained with Hoechst (white). Bars, 20 µm. (C) Q-PCR analysis of the expression of pre- and postmeiotic genes in single round spermatids of Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− mice, normalized by the mean of Ppia and Arbp, and shown as the fold expression difference from the average in the log2 scale (error bars).

Genes critical for meiosis, such as Mvh, Scp1, Scp3, and Hsc70-2, as well as the housekeeping genes Ppia, Arbp, and Gapdh, were expressed similarly in both the wild-type and Tdrd5−/− mutant testes (Fig. 8 A). Miwi showed a lower expression at P20 in Tdrd5−/− mutants than in the wild type, but at P25, the expression level in Tdrd5−/− mutants recovered to nearly the level in the wild type (Fig. 8 A). Crem, a gene encoding a “master” transcription factor for spermiogenesis (Blendy et al., 1996; Nantel et al., 1996), also showed a lower expression in Tdrd5−/− mutants at P20, but it exhibited a similar expression level at P25 in the Tdrd5−/− mutants and wild type (Fig. 8 A). Trf2, a gene encoding a TATA binding protein (TBP)-related factor essential for a later event of spermiogenesis (Martianov et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2001), exhibited a similar expression pattern (Fig. 8 A). These findings indicate that known transcription factors essential for spermiogenesis are expressed normally in round spermatids in the absence of TDRD5, although these factors as well as Miwi show lower expression in meiotic germ cells. We confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis that CREM is expressed similarly in the round spermatids of Tdrd5−/− mutants and wild type (Fig. 8 B).

Notably, however, Act, a gene encoding the testis-specific coactivator of CREM (Fimia et al., 1999), is greatly reduced in the Tdrd5−/− mutant at P25 (Fig. 8 A). Similarly, putative targets of CREM, such as Prm1, Prm2, Tnp1, Calspermin, and RT7, were reduced in the Tdrd5−/− mutant at P25 (Fig. 8 A). These findings indicate that the failure of spermiogenesis in Tdrd5−/− mutants is caused by the reduced expression of CREM target genes in round spermatids.

To confirm that genes such as Prm1, Prm2, and Tnp1 are truly reduced in round spermatids in Tdrd5−/− mutants, we prepared cDNAs from single round spermatids of Tdrd5−/− mutants as well as of the wild type. Tdrd5-deficient single round spermatids expressed Crem at a level similar to that in wild-type cells, but they showed a reduced expression of Act, Prm1, Prm2, Tnp1, and RT7 (Fig. 8 C). Collectively, these findings suggest the presence of a mechanism involved in TDRD5, which regulates the proper expression of key genes for spermiogenesis, some of which are the targets of the CREM transcription factor.

Fertile offspring from round spermatids of the Tdrd5−/− mutants

The results described so far show that TDRD5 has a critical function in the repression of retrotransposons, in the assembly of the IMCs and CBs, and in spermiogenesis. To examine whether the remaining round spermatids in Tdrd5−/− mutants might harbor a functional haploid genome, we decided to perform a round spermatid injection (ROSI; Ogura et al., 1994; Ohta et al., 2009). We injected 105 and 153 oocytes with round spermatids from Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− animals, respectively (Table I). The oocytes injected with round spermatids from Tdrd5−/− mice developed into two-cell embryos at a similar ratio to that of oocytes injected with the wild-type round spermatids (104 out of 105 [99.0%] for the wild type and 151 out of 153 [98.7%] for the Tdrd5−/− mutants; Table I). These embryos were transferred into foster mothers to evaluate their ability to develop further. Strikingly, embryos from the round spermatids of Tdrd5−/− mice gave rise to offspring at a similar ratio to those from wild-type round spermatids (Table I). The offspring as well as the placenta from round spermatids of Tdrd5−/− mice looked grossly normal and had similar weights to those from wild-type round spermatids (Table II and Fig. S5). Furthermore, the offspring from round spermatids of Tdrd5−/− mice appeared to develop normally and became fully fertile. These findings demonstrate that TDRD5 function is independent from the formation of a haploid genome with proper function.

Table I.

Development of oocytes injected with round spermatids from wild-type and Tdrd5−/− mice

| Genotype | No. of injected oocytes | No. of two-cell | No. of ET | No. of progeny |

| +/+ | 105 | 104 (99.0%)a | 104 | 16 (15.4%)b |

| −/− | 153 | 151 (98.7%)a | 151 | 25 (16.6%)b |

Four independent experiments using two males were performed for each genotype. No statistically significant difference was found by Fisher’s exact probability test. ET, embryo transfer.

P = 1.000.

P = 0.863.

Table II.

Body and placenta weights of newborn mice derived from round spermatids from wild-type and Tdrd5−/− germ cells

| Genotype | Body weight | Placenta weight |

| g | g | |

| +/+ | 1.36 ± 0.17 (n = 16)a | 0.18 ± 0.04 (n = 16)b |

| −/− | 1.34 ± 0.14 (n = 25)a | 0.18 ± 0.02 (n = 25)b |

The mean ± SD is shown. No statistically significant difference was found by Student’s t test.

P = 0.57.

P = 0.61.

Discussion

Recent studies have shown that TDRDs are critical regulators of spermatogenesis in mice (Pan et al., 2005; Chuma et al., 2006; Shoji et al., 2009; Vasileva et al., 2009). Based on their expression and the spermatogenic stages by which the phenotypes manifest in mutant animals, TDRDs can be classified into two groups: those that show expression from embryonic germ cells and are critical for progression of the meiotic prophase, and those that begin their expression in neonatal germ cells, show prominent expression from the pachytene stage onwards, and are essential for spermiogenesis. The first group includes TDRD1 and TDRD9 (Chuma et al., 2006; Shoji et al., 2009) and the second group includes TDRD4/RNF17 and TDRD6 (Pan et al., 2005; Vasileva et al., 2009). A key phenotype of the first group of mutants is the derepression of retrotransposons, especially the LINE-1 elements, and the consequent meiotic catastrophe (Chuma et al., 2006; Reuter et al., 2009; Shoji et al., 2009), whereas the second group of mutants go through meiosis but fail to establish proper postmeiotic gene expression despite their normal expression of key transcriptional regulators for spermiogenesis, such as CREM and TATA Box-binding protein–related factor, TBPL1 (TRF2; Pan et al., 2005; Vasileva et al., 2009).

We have provided evidence that Tdrd5 begins its expression as early as E7.25 in PGCs and continues to be expressed in the male germ line up until the round-spermatid stage (Fig. 1, D, E, and I). Our analysis has demonstrated that TDRD5 is a novel component of the IMCs (pi-bodies) and the CBs, but not piP-bodies (Fig. 2). We have also identified T/PNBs bearing proteins with sDMA in mid-to-late pachytene spermatocytes (Fig. S2). Loss of TDRD5 leads to an impaired assembly of IMCs and CBs (Figs. 5 and 6), a failure in the repression of LINE-1 (Fig. 7), the sterility of the male animals, and, although perhaps to a milder extent, a failure in spermiogenesis (Fig. 4) because of substantial defects in postmeiotic gene expression (Fig. 8). Thus, TDRD5 is a unique member of the TDRDs, with functions both in retrotransposon repression and in the progression of spermiogenesis.

In Tdrd1 or Tdrd9 mutants, the spermatogenesis is arrested at the meiotic prophase with accumulation of the LINE-1 mRNAs and ORF1p in the nuclei of the spermatocytes (Reuter et al., 2009; Shoji et al., 2009). Similarly, in Tdrd5−/− mutants, the LINE-1 was de-repressed and ORF1p was accumulated in the cytoplasm of prospermatogonia as well as of meiotic spermatocytes, and the promoter sequences of the LINE-1 elements were demethylated (Fig. 7). In Tdrd5−/− mutants, MIWI2 and TDRD9 were largely excluded from the nucleus and were confined to the cytoplasm in the prospermatogonia at both E17.5 and at P2 (Fig. 5 B), a critical period for DNA remethylation on the retrotransposon sequences (Kato et al., 2007; Schaefer et al., 2007; Sasaki and Matsui, 2008). A similar exclusion of MIWI2 from the nucleus was seen in the cases of Tdrd1 and Mili−/− mutants (Aravin et al., 2008; Reuter et al., 2009). These findings are consistent with the finding that piP-bodies are under the control of the IMCs (pi-bodies; Shoji et al., 2009). However, in contrast to Tdrd1 or Tdrd9−/− mutants, Tdrd5−/− mutants went through meiotic prophase relatively normally and managed to form round spermatids, although they did manifest sporadic meiotic failure (Fig. 4). This would be because the extent of the LINE-1 derepression is milder in Tdrd5−/− mutants than in Tdrd1 or Tdrd9−/− mutants. Consistently, in Tdrd5−/− mutants, we only infrequently observed strong accumulation of ORF1p in the nuclei of the spermatocytes, key features found in Tdrd9−/− or Mael−/− mutants (Soper et al., 2008; Shoji et al., 2009). What determines the extent of transposon derepression is unknown and warrants further studies. TDRD1 and TDRD5 showed almost perfect colocalization at the IMCs (pi-bodies) in the prospermatogonia and in the pachytene spermatocytes as well as at the CBs in the round spermatids, whereas TDRD9 localizes at clearly distinct piP-bodies in the prospermatogonia (Fig. 2; Shoji et al., 2009). The different phenotypic consequence between Tdrd1 and Tdrd5 mutants indicates a subtle but clear difference between TDRD1 and TDRD5 in the role for the functional assembly of the IMCs. Notably, although TDRD1 exhibited prominent spotted localization in the nuclei of prospermatogonia, TDRD5 did not (Fig. 2 D). This may also reflect a functional difference between TDRD1 and TDRD5.

The key phenotype of the Tdrd5−/− mutants was the arrest of the spermiogenesis at the round spermatid stage (Fig. 4), which is also the case for the Tdrd4/Rnf17, Tdrd6, and Miwi−/− mutants (Deng and Lin, 2002; Pan et al., 2005; Vasileva et al., 2009). In mutants for Tdrd4/Rnf17, Miwi, and Tdrd5, CREM, a “master” transcription factor for spermiogenesis, was expressed normally, but its target genes were significantly reduced (Fig. 8; Deng and Lin, 2002; Pan et al., 2005). It is of note that the expression of a testis-specific coactivator of CREM, ACT, was significantly reduced in all three mutants (Fig. 8; Deng and Lin, 2002; Pan et al., 2005). This would indicate that the CREM–ACT complex is not formed as efficiently as in the wild types in these mutants, leading to the reduced expression of its target genes. MIWI forms a complex with Act mRNA as well as with some target genes of CREM, thereby perhaps regulating their stability (Deng and Lin, 2002). Considering that TDRD5 precisely colocalizes with MIWI at the IMCs, CBs, and T/PNBs, and that the IMCs and the CBs were significantly disorganized and the localization of MIWI was highly impaired in Tdrd5−/− mutants (Fig. 2, E and F; Fig. 5, C and D; and Fig. 6), the reduced expression of Act and CREM target genes in the Tdrd5−/− mutants may also be a consequence of their destabilization at the cytoplasm. It is also interesting to note that the frequency of T/PNB-positive mid-pachytene–to–diplotene spermatocytes increased in Tdrd5−/− mutants (Fig. S2), which suggests that a loss of IMC/CB function may disrupt recycling of their components from the nucleus. However, it is interesting to note that TDRD4/RNF17 forms cytoplasmic granules distinct from the IMCs and the CBs (Pan et al., 2005). Considering that the phenotype of Tdrd4/Rnf17−/− mutants is similar to that of Tdrd5 and Miwi−/− mutants, the TDRD4/RNF17-based granules may function cooperatively with the IMCs and the CBs for the stabilization of the CREM target genes and other spermiogenic genes.

Despite the pronounced phenotypes in the spermatogenesis of the Tdrd5−/− mutants, the ROSI experiments demonstrated that the haploid genome developed in the absence of TDRD5 functions normally: it contributed successfully to the generation of fertile offspring (Tables I and II). This shows that the function of TDRD5 can be uncoupled from the acquisition of a functional male haploid genome. This also raises the possibility that the mutants for Tdrd4, Tdrd6, or Miwi, which show phenotypes similar to those of Tdrd5, bear round spermatids with a functional haploid genome. The validation of this possibility would be important to clarify the function of these gene products in the acquisition of a proper haploid genome. In conclusion, we have identified TDRD5 as a novel component of the IMCs and CBs as well as of newly identified T/PNBs, and have revealed an essential function of TDRD5 in spermiogenesis. Our study also shows the finely organized and distinct subcellular distribution of TDRDs, which suggests their functional diversity. Further studies will be needed to more fully elucidate the mechanism of action of TDRDs in male germ cell development.

Materials and methods

Animals

All the animal experiments were performed under the ethical guidelines of Kyoto University and RIKEN. Noon of the day when the vaginal plugs of mated females were identified was scored as E0.5.

Northern hybridization, RT-PCR, and Q-PCR

Total RNA samples from embryonic gonads and adult tissues were prepared using TRIzol (Invitrogen) or an RNeasy micro kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription reaction with the dT24 primer was performed using Superscript III Reverse transcription (Invitrogen). The single-cell cDNAs of E7.25, E8.25, and E10.5 PGCs and E7.25 somatic cells surrounding PGCs were prepared as described previously (Kurimoto et al., 2008; Yamaguchi et al., 2009). PCR was performed using the gene-specific primers listed in Table S1. Q-PCR was performed using a 7900 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequences of the primers for the genes examined are listed in Table S1. Northern hybridization was performed at 42°C in UltraHyb buffer (Applied Biosystems) with probes labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using a High Prime DNA Labeling kit (Roche).

Generation of anti-TDRD5 antibody and Western blotting

A peptide fragment of TDRD5 (Swiss-Prot accession No. Q5VCS6; amino acids 837–850) was synthesized and used for immunization of rabbits for the generation of polyclonal antibodies. The obtained serum was purified with immuno-affinity chromatography by using the synthetic peptide used for immunization. Embryonic gonads and testes were homogenized in a 1.5-ml microtube with 10 µl of the SDS sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 6% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, and Bromophenol blue) per embryonic gonad or in a Dounce homogenizer with 2 ml of the sample buffer per 100 µg testis with 20 strokes, respectively. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). The blot was incubated with a blocking solution (0.2% Tween 20 and 2% ECL Advance Blocking Reagent [GE Healthcare] in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature, then incubated in PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20 (PBT) with the primary antibody (anti-TDRD5 antibody, 1:4,000; or anti–α-tubulin [T9026; Sigma-Aldrich], 1:8,000) for 1 h at room temperature. The blot was washed three times with PBT and then incubated in PBT with the secondary antibody (peroxidase-labeled anti–rabbit IgG [NA934vs; GE Healthcare], 1:25,000; or peroxidase-labeled anti–mouse IgG antibody [NA931vs; GE Healthcare], 1:10,000). After washing three times with PBT, signals were detected by using ECL plus Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare).

Generation of Tdrd5-EGFP reporter mice

A mouse BAC clone containing Tdrd5 (RP24-129L5) was purchased from the BACPAC Resource Center. EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) was recombined into the end of the open reading frame of Tdrd5 by Red/ET recombineering (Gene Bridges) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The construct was digested with NotI and purified through a column bearing CL-4B Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for injection into the pronuclei of BL6/DBA F2 zygotes to generate transgenic mice. The TDRD5-EGFP reporter mice (accession No. CDB0469T) were genotyped by PCR with the GFP genotype primers (see Table S1).

Immunofluorescence antibody staining

The testes were decapsulated, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 h, treated with 15% and 30% sucrose in PBS, and then embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek USA Inc.). The embedded testes were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and were sectioned by a Cryostat (Leica) at a thickness of 10 µm. The cryosections were blocked with a blocking buffer (5% normal goat serum [Vector Laboratories] in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature or overnight at 4°C, and incubated in the blocking buffer with the primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-TDRD5 (1:2,000), anti-GFP (1:500; 04404-84; Nacalai Tesque Inc.), anti-TDRD1 (1:1,000; Chuma et al., 2003), anti-TDRD6 (1:1,000; Hosokawa et al., 2007), anti-TDRD7 (1:1,000; Hosokawa et al., 2007), anti-TDRD9 (1:1,000; Shoji et al., 2009), anti-PIWIL1/MIWI (1:200, 2079; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-PIWIL2/MILI (1:500, ab36764; Abcam), anti-PIWIL4/MIWI2 (1:1,000, ab21869; Abcam), anti-DDX4/MVH (1:250, ab13840; Abcam), anti-DCP1a (1:100, WH0055802M6; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-ORF1p (1:500, a gift from S.L. Martin, University of Colorado, Aurora, CO), anti-SCP3 (1:750, GTX15092; GeneTex), anti-phosphorylated H2A.X (anti-γH2AX; 1:500, 05-636; Millipore), anti-Golgi-58K (1:100, G2404; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-histone H2A + H4 (symmetric dimethyl R3; 1:1,000, ab5823; Abcam), anti–human CREST serum (1:100, CS1058; Fitzgerald Industries), anti-B23/NPM1 (1:200, B0556; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-CREM (1:100, ab64832; Abcam), and rhodamine peanut agglutinin (1:500, RL-1072; Vector Laboratories). The sections were then washed three times with PBS for 5 min each and were incubated in the blocking buffer with the secondary antibody (1:500; Alexa Fluor 488– or 568–conjugated goat anti–rabbit, goat anti–rat, or goat anti–mouse IgG antibodies, and 1 µg/ml Hoechst). They were then washed three times with PBS for 5 min each and embedded in Vectashield for observation. Confocal microscopy was performed at room temperature with a laser-scanning microscope (FV1000; Olympus) using a UPlan-SApochromat 100× 1.40 NA oil immersion objective lens and acquisition software (FV10-ASW ver. 2.1c). For TDRD9 detection in embryonic gonads, an E17.5 male gonad was directly frozen in OCT compound without fixing and sectioned at a thickness of 10 µm. The section was fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature and immunostained as described earlier in this paragraph.

Generation of Tdrd5 knockout mice

The BAC clone TP24-129L5 was used to amplify short (∼2.6 kb) and long (∼6.7 kb) homologous arms of the targeting vector using primer the pairs of Tdrd5-SA and Tdrd5-LA, respectively (Table S1). The amplified short and long arms were subcloned between the XhoI and NheI sites and between the NotI and SalI sites, respectively, of the vector, DT-A-pA/loxP/PGK-Neo-pA/loxP (CDB LARGE). The targeting vector was linearized with SalI and electroporated into the TT2 ESC line (Yagi et al., 1993). Potential homologous recombinants were screened by PCR using the primer pair of Tdrd5-sc-F and Neo-gt-1 (Table S1) and were confirmed by Southern blot analysis using the 5′ probe (amplification primers: Tdrd5 genotype; Table S1), the 3′ probe, and the Neo probe. Chimeric mice were generated by injecting the two independent homologous recombinants into the eight-cell-stage embryos of the ICR mice (Yagi et al., 1993). High-contribution chimeras judged by their coat color were mated with C57BL/6 females to confirm the germline transmission of the ESCs. The Tdrd5 heterozygous+/− mice were genotyped by PCR using Tdrd5-genotype1, Tdrd5-genotype2, and Neo-genotype primers (Table S1) and were used to obtain Tdrd5 homozygous−/− mice. The Tdrd5 heterozygous+/− mice (accession No. CDB0603K) were maintained by internal crosses as well as by backcrosses on the C57BL/6 background.

Southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA was digested with restriction enzymes, run on 0.8% agarose gels, and blotted onto the Hibond-N+ membranes (GE Healthcare). Hybridization was performed at 65°C in 0.5 M sodium-phosphate, pH 7.2, 1 mM EDTA, and 7% SDS with probes radio-labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using a High Prime DNA labeling kit. For DNA methylation analysis, genomic DNA prepared from P14 or P25 testes was digested with the restriction enzyme MspI, HpaII, or HpyCH4III, then hybridized with probes labeled using [α-32P]dCTP and a High Prime DNA labeling kit. Probes for SINE-B1 and Major satellite were end-labeled using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Inc.).

Histology and the detection of apoptosis

Testes were dissected, weighed, and fixed in Bouin’s fixative overnight, then embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned at a thickness of 6 µm by a microtome (Leica), mounted on glass slides (MAS-GP; Matsunami Glass), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For the detection of apoptotic cells, the sections were immunostained with anti–activated caspase-3 antibody (1:250; G7481; Promega) and visualized with a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) and ImmPACT DAB peroxidase substrate (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Nuclear spread preparations

Nuclear spreads of testis cells were prepared as described previously (Moens and Pearlman, 1991) with some modifications. In brief, the capsule-removed testis was mildly homogenized in PBS in a 2-ml microtube with a plastic homogenizer and filtered through a cell strainer with a 40-µm pore size (Falcon). 200 µl of the filtered sample was dropped onto a poly-l-lysine–coated cover glass to anchor the cells on the surface of the glass. The cover glass was then treated with 0.5% NaCl for 3 min, 1% paraformaldehyde with 0.03% SDS for 3 min, and 1% paraformaldehyde for 3 min on ice, then washed with 4% drywell (Fuji) three times before air drying. The spreads were stained with anti-SCP3 and γH2AX antibodies as described in the section on immunofluorescence antibody staining.

Electron microscopy

Under deep anesthesia, animals were killed by intracardiac perfusion with a solution of 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4. The tissues were excised and further fixed in the same fixative for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, (pH 7.4, three times for 5 min each), they were postfixed with ice-cold 1% OsO4 in the same buffer for 2 h. The samples were rinsed with distilled water, stained with 0.5% aqueous uranyl acetate for 2 h or overnight at room temperature, dehydrated with ethanol, and embedded in Poly/Bed 812. Ultrathin sections were cut, doubly stained with uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate, and viewed with a JEM 1010 transmission electron microscope (JEOL) at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV.

Single-cell cDNA amplification from round spermatids

Wild-type and Tdrd5−/− testes were decapsulated and mildly homogenized in PBS, then round spermatids were isolated under a micromanipulator (IX71; Olympus). Single-cell cDNAs from isolated single round spermatids were amplified as described previously (Kurimoto et al., 2006, 2007). The amplified cDNA samples were screened by Q-PCR using Arbp and Ppia for cDNA amplification quality and Mvh for germ cells. Q-PCR for premeiotic and postmeiotic genes was performed on fifteen single-cell cDNA samples from wild-type and Tdrd5−/− cells, and the obtained cycles threshold values were normalized by the averaged cycles threshold of Arbp and Ppia.

ROSI

Superovulation was induced in BDF1 females by injecting 5 IU equine chorionic gonadotropin, followed by a second injection of 5 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 48 h later. At 14 h after hCG injection, the cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) were collected from the oviducts. Oocytes were freed from the cumulus cells by adding 0.1% bovine testicular hyaluronidase (ICN Biochemicals) to the COC-containing medium. After the cumulus cells had been dissociated, the oocytes were cultured using KSOM medium (Millipore).

ROSI was performed according to a previously described procedure with minor modifications (Ohta et al., 2009). The testicular cell suspension was prepared from an adult male homozygous mutant for Tdrd5, or a wild-type male from the same breeding colony (Tdrd5+/− × Tdrd5+/−). In brief, the testis was decapsulated, minced with fine scissors, suspended in KSOM medium, and used for ROSI. Injection of round spermatids into oocytes was performed with a Piezo-actuated micromanipulator. To activate oocytes that received round spermatids, they were placed in Ca2+-free CZB medium containing 10 mM SrCl2 at 15–20 min after the injection and then cultured for 1 h (Ogura et al., 1994; Ohta et al., 2009). After the activation, zygotes were cultured in KSOM medium at 37°C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2. When the embryos reached the two-cell stage, they were transferred to the oviducts of 0.5-d postcoitus (dpc) pseudopregnant ICR females and analyzed at 18.5 dpc.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows TDRD5 expression in the embryonic gonads and postnatal testis, and the rescue of Tdrd5−/− phenotype by the TDRD5-EGFP transgene. Fig. S2 shows T/PNBs in mid-to-late pachytene spermatocytes. Fig. S3 shows MIWI2 and ORF1p expression in perinatal testes of Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− mice. Fig. S4 shows first-round spermatogenesis of Tdrd5+/+ and Tdrd5−/− animals. Fig. S5 shows the generation of normal offspring from round spermatids of a Tdrd5−/− mutant animal. Table S1 lists all primer pairs and probe sequences used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra L. Martin for the anti-ORF1p antibody and Peter Koopman for sharing information. We are grateful to Shigenobu Yonemura and Sachiko Onishi for their assistance with the electron microscopy and Mayo Shigeta and Kaori Yamanaka for their help in the maintenance of mice.

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology, and by the Takeda Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- BAC

- bacterial artificial chromosome

- CB

- chromatoid body

- CREM

- cyclic AMP response element modulator

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- IAP

- intracisternal A particle

- IMC

- inter-mitochondrial cement

- LINE-1

- long interspersed repetitive element 1

- MILI

- mouse homologue of PIWI, PIWIL2

- MIWI

- mouse homologue of PIWI, PIWIL1

- MVH

- mouse vasa homologue

- ORF

- open reading frame

- ORF1p

- ORF1 coding protein of LINE-1

- PGC

- primordial germ cell

- piRNA

- PIWI-interacting RNA

- PIWI

- P element–induced wimpy testis

- Q-PCR

- quantitative PCR

- ROSI

- round spermatid injection

- sDMA

- symmetric dimethylated arginine

- SINE-B1

- short interspersed repetitive element B1

- TDRD

- Tudor-domain containing protein

- T/PNB

- Tudor/Piwi-containing nuclear body

- TRF2

- TATA Box-binding protein–related factor, TBPL1

References

- Anantharaman V., Zhang D., Aravind L. 2010. OST-HTH: a novel predicted RNA-binding domain. Biol. Direct. 5:13 10.1186/1745-6150-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin A.A., Sachidanandam R., Bourc’his D., Schaefer C., Pezic D., Toth K.F., Bestor T., Hannon G.J. 2008. A piRNA pathway primed by individual transposons is linked to de novo DNA methylation in mice. Mol. Cell. 31:785–799 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin A.A., van der Heijden G.W., Castañeda J., Vagin V.V., Hannon G.J., Bortvin A. 2009. Cytoplasmic compartmentalization of the fetal piRNA pathway in mice. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000764 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkov A.L., Wang J.Y., Ramos A., Lehmann R. 2006. The role of Tudor domains in germline development and polar granule architecture. Development. 133:4053–4062 10.1242/dev.02572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellvé A.R., Cavicchia J.C., Millette C.F., O’Brien D.A., Bhatnagar Y.M., Dym M. 1977. Spermatogenic cells of the prepuberal mouse. Isolation and morphological characterization. J. Cell Biol. 74:68–85 10.1083/jcb.74.1.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendy J.A., Kaestner K.H., Weinbauer G.F., Nieschlag E., Schütz G. 1996. Severe impairment of spermatogenesis in mice lacking the CREM gene. Nature. 380:162–165 10.1038/380162a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell R.E., Mahowald A.P. 1985. tudor, a gene required for assembly of the germ plasm in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell. 43:97–104 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90015-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J., Koopman P. 2010. Sex determination in mammalian germ cells: extrinsic versus intrinsic factors. Reproduction. 139:943–958 10.1530/REP-10-0075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut I., Mornon J.P. 2010. LOTUS, a new domain associated with small RNA pathways in the germline. Bioinformatics. 26:1140–1144 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmell M.A., Girard A., van de Kant H.J., Bourc’his D., Bestor T.H., de Rooij D.G., Hannon G.J. 2007. MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Dev. Cell. 12:503–514 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuma S., Hiyoshi M., Yamamoto A., Hosokawa M., Takamune K., Nakatsuji N. 2003. Mouse Tudor Repeat-1 (MTR-1) is a novel component of chromatoid bodies/nuages in male germ cells and forms a complex with snRNPs. Mech. Dev. 120:979–990 10.1016/S0925-4773(03)00181-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuma S., Hosokawa M., Kitamura K., Kasai S., Fujioka M., Hiyoshi M., Takamune K., Noce T., Nakatsuji N. 2006. Tdrd1/Mtr-1, a tudor-related gene, is essential for male germ-cell differentiation and nuage/germinal granule formation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:15894–15899 10.1073/pnas.0601878103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuma S., Hosokawa M., Tanaka T., Nakatsuji N. 2009. Ultrastructural characterization of spermatogenesis and its evolutionary conservation in the germline: germinal granules in mammals. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 306:17–23 10.1016/j.mce.2008.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W., Lin H. 2002. miwi, a murine homolog of piwi, encodes a cytoplasmic protein essential for spermatogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2:819–830 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00165-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy E.M. 1975. Germ plasm and the differentiation of the germ cell line. Int. Rev. Cytol. 43:229–280 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60070-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edson M.A., Nagaraja A.K., Matzuk M.M. 2009. The mammalian ovary from genesis to revelation. Endocr. Rev. 30:624–712 10.1210/er.2009-0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fimia G.M., De Cesare D., Sassone-Corsi P. 1999. CBP-independent activation of CREM and CREB by the LIM-only protein ACT. Nature. 398:165–169 10.1038/18237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodier J.L., Kazazian H.H., Jr 2008. Retrotransposons revisited: the restraint and rehabilitation of parasites. Cell. 135:23–35 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivna S.T., Beyret E., Wang Z., Lin H. 2006a. A novel class of small RNAs in mouse spermatogenic cells. Genes Dev. 20:1709–1714 10.1101/gad.1434406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivna S.T., Pyhtila B., Lin H. 2006b. MIWI associates with translational machinery and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) in regulating spermatogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:13415–13420 10.1073/pnas.0605506103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa M., Shoji M., Kitamura K., Tanaka T., Noce T., Chuma S., Nakatsuji N. 2007. Tudor-related proteins TDRD1/MTR-1, TDRD6 and TDRD7/TRAP: domain composition, intracellular localization, and function in male germ cells in mice. Dev. Biol. 301:38–52 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y., Kaneda M., Hata K., Kumaki K., Hisano M., Kohara Y., Okano M., Li E., Nozaki M., Sasaki H. 2007. Role of the Dnmt3 family in de novo methylation of imprinted and repetitive sequences during male germ cell development in the mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16:2272–2280 10.1093/hmg/ddm179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi-Miyagawa S., Kimura T., Yomogida K., Kuroiwa A., Tadokoro Y., Fujita Y., Sato M., Matsuda Y., Nakano T. 2001. Two mouse piwi-related genes: miwi and mili. Mech. Dev. 108:121–133 10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00499-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi-Miyagawa S., Kimura T., Ijiri T.W., Isobe T., Asada N., Fujita Y., Ikawa M., Iwai N., Okabe M., Deng W., et al. 2004. Mili, a mammalian member of piwi family gene, is essential for spermatogenesis. Development. 131:839–849 10.1242/dev.00973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi-Miyagawa S., Watanabe T., Gotoh K., Totoki Y., Toyoda A., Ikawa M., Asada N., Kojima K., Yamaguchi Y., Ijiri T.W., et al. 2008. DNA methylation of retrotransposon genes is regulated by Piwi family members MILI and MIWI2 in murine fetal testes. Genes Dev. 22:908–917 10.1101/gad.1640708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurimoto K., Yabuta Y., Ohinata Y., Ono Y., Uno K.D., Yamada R.G., Ueda H.R., Saitou M. 2006. An improved single-cell cDNA amplification method for efficient high-density oligonucleotide microarray analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:e42 10.1093/nar/gkl050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurimoto K., Yabuta Y., Ohinata Y., Saitou M. 2007. Global single-cell cDNA amplification to provide a template for representative high-density oligonucleotide microarray analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2:739–752 10.1038/nprot.2007.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurimoto K., Yabuta Y., Ohinata Y., Shigeta M., Yamanaka K., Saitou M. 2008. Complex genome-wide transcription dynamics orchestrated by Blimp1 for the specification of the germ cell lineage in mice. Genes Dev. 22:1617–1635 10.1101/gad.1649908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martianov I., Fimia G.M., Dierich A., Parvinen M., Sassone-Corsi P., Davidson I. 2001. Late arrest of spermiogenesis and germ cell apoptosis in mice lacking the TBP-like TLF/TRF2 gene. Mol. Cell. 7:509–515 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00198-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S.L., Branciforte D. 1993. Synchronous expression of LINE-1 RNA and protein in mouse embryonal carcinoma cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:5383–5392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer-Stroh S., Dickens N.J., Hughes-Davies L., Kouzarides T., Eisenhaber F., Ponting C.P. 2003. The Tudor domain ‘Royal Family’: Tudor, plant Agenet, Chromo, PWWP and MBT domains. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:69–74 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren A. 2003. Primordial germ cells in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 262:1–15 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00214-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens P.B., Pearlman R.E. 1991. Visualization of DNA sequences in meiotic chromosomes. Methods Cell Biol. 35:101–108 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)60570-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantel F., Monaco L., Foulkes N.S., Masquilier D., LeMeur M., Henriksén K., Dierich A., Parvinen M., Sassone-Corsi P. 1996. Spermiogenesis deficiency and germ-cell apoptosis in CREM-mutant mice. Nature. 380:159–162 10.1038/380159a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura A., Matsuda J., Yanagimachi R. 1994. Birth of normal young after electrofusion of mouse oocytes with round spermatids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:7460–7462 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta H., Sakaide Y., Wakayama T. 2009. Functional analysis of male mouse haploid germ cells of various differentiation stages: early and late round spermatids are functionally equivalent in producing progeny. Biol. Reprod. 80:511–517 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J., Goodheart M., Chuma S., Nakatsuji N., Page D.C., Wang P.J. 2005. RNF17, a component of the mammalian germ cell nuage, is essential for spermiogenesis. Development. 132:4029–4039 10.1242/dev.02003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil V.S., Kai T. 2010. Repression of retroelements in Drosophila germline via piRNA pathway by the tudor domain protein Tejas. Curr. Biol. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips B.T., Gassei K., Orwig K.E. 2010. Spermatogonial stem cell regulation and spermatogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365:1663–1678 10.1098/rstb.2010.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter M., Chuma S., Tanaka T., Franz T., Stark A., Pillai R.S. 2009. Loss of the Mili-interacting Tudor domain-containing protein-1 activates transposons and alters the Mili-associated small RNA profile. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:639–646 10.1038/nsmb.1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson B.E., Lehmann R. 2010. Mechanisms guiding primordial germ cell migration: strategies from different organisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:37–49 10.1038/nrm2815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou M., Yamaji M. 2010. Germ cell specification in mice: signaling, transcription regulation, and epigenetic consequences. Reproduction. 139:931–942 10.1530/REP-10-0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H., Matsui Y. 2008. Epigenetic events in mammalian germ-cell development: reprogramming and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9:129–140 10.1038/nrg2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer C.B., Ooi S.K., Bestor T.H., Bourc’his D. 2007. Epigenetic decisions in mammalian germ cells. Science. 316:398–399 10.1126/science.1137544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji M., Tanaka T., Hosokawa M., Reuter M., Stark A., Kato Y., Kondoh G., Okawa K., Chujo T., Suzuki T., et al. 2009. The TDRD9-MIWI2 complex is essential for piRNA-mediated retrotransposon silencing in the mouse male germline. Dev. Cell. 17:775–787 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi M.C., Mannen T., Siomi H. 2010. How does the royal family of Tudor rule the PIWI-interacting RNA pathway? Genes Dev. 24:636–646 10.1101/gad.1899210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.M., Bowles J., Wilson M., Teasdale R.D., Koopman P. 2004. Expression of the tudor-related gene Tdrd5 during development of the male germline in mice. Gene Expr. Patterns. 4:701–705 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper S.F., van der Heijden G.W., Hardiman T.C., Goodheart M., Martin S.L., de Boer P., Bortvin A. 2008. Mouse maelstrom, a component of nuage, is essential for spermatogenesis and transposon repression in meiosis. Dev. Cell. 15:285–297 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin V.V., Wohlschlegel J., Qu J., Jonsson Z., Huang X., Chuma S., Girard A., Sachidanandam R., Hannon G.J., Aravin A.A. 2009. Proteomic analysis of murine Piwi proteins reveals a role for arginine methylation in specifying interaction with Tudor family members. Genes Dev. 23:1749–1762 10.1101/gad.1814809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileva A., Tiedau D., Firooznia A., Müller-Reichert T., Jessberger R. 2009. Tdrd6 is required for spermiogenesis, chromatoid body architecture, and regulation of miRNA expression. Curr. Biol. 19:630–639 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Saxe J.P., Tanaka T., Chuma S., Lin H. 2009. Mili interacts with tudor domain-containing protein 1 in regulating spermatogenesis. Curr. Biol. 19:640–644 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi T., Tokunaga T., Furuta Y., Nada S., Yoshida M., Tsukada T., Saga Y., Takeda N., Ikawa Y., Aizawa S. 1993. A novel ES cell line, TT2, with high germline-differentiating potency. Anal. Biochem. 214:70–76 10.1006/abio.1993.1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S., Kurimoto K., Yabuta Y., Sasaki H., Nakatsuji N., Saitou M., Tada T. 2009. Conditional knockdown of Nanog induces apoptotic cell death in mouse migrating primordial germ cells. Development. 136:4011–4020 10.1242/dev.041160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S. 2010. Stem cells in mammalian spermatogenesis. Dev. Growth Differ. 52:311–317 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2010.01174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Penttila T.L., Morris P.L., Teichmann M., Roeder R.G. 2001. Spermiogenesis deficiency in mice lacking the Trf2 gene. Science. 292:1153–1155 10.1126/science.1059188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]