Abstract

Objective

Prior studies largely performed at tertiary care centers with relatively young, racially homogenous cohorts found a short PSA doubling time (PSADT) following recurrence after radical prostatectomy (RP) portends a poor prognosis. We examined the correlation between PSADT and overall survival (OS) and among men in the SEARCH database, an older, racially diverse cohort treated with RP at multiple Veterans Affairs medical centers.

Methods

We performed a Cox proportional hazards analysis to examine the correlation between post-recurrence PSADT and time from recurrence to OS and PCSM among 345 men in the SEARCH database who underwent RP between 1988 and 2008. We examined PSADT as a categorical variable based on the clinically significant cut-points of <3, 3-8.9, 9–14.9, and ≥15 months.

Results

PSADT <3 months (HR 5.48, p=0.002) was associated with poorer OS versus PSADT ≥15 months. There was a trend towards worse OS among men with a PSADT of 3–8.9 months (HR=1.70, p=0.07). PSADT <3 months (p<0.001) and 3–8.9 months (p=0.004) were associated with increased risk of PCSM.

Conclusions

In an older, racially diverse cohort, recurrence with a PSADT <9 months was associated with worse all-cause mortality. This study validates prior findings that PSADT is a useful tool for identifying men who are at increased risk of all-cause mortality early in the course of their disease.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, PSADT, Biochemical recurrence, tumor markers

INTRODUCTION

The first paper to suggest PSA rises after radical prostatectomy (RP) were associated with long-term outcomes was published 15 years ago.1 Since then, many have explored the correlation between post-RP PSA doubling time (PSADT) and various prostate cancer (PC) end-points. PSADT has been shown to predict PC-specific mortality (PCSM).2–6 Others found a short post-RP PSADT portends a poor prognosis and response to salvage treatment.7–11 However, many of these observations were in populations of relatively young, racially homogenous men from tertiary care centers.2–5 Therefore, these men likely had fewer competing mortality causes and medical comorbidities than men from equal access centers like Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals. There has only been one study examining the correlation between PSADT and PCSM in an older, more racially diverse cohort.6 It compared men with a very short PSADT (<3 months) with those with a PSADT >3 months and found men with short PSADT had an increased PCSM risk. However, it did not examine the correlation between PSADT and PCSM among men with intermediate PSADT values (i.e., 3–15 months). Moreover, despite widespread acceptance that PSADT after RP predicts PCSM, the degree to which it correlates with OS is understudied. Only one study examined this issue among men with intermediate PSADTs, and while it found PSADT predicted OS, the cohort was a relatively young, healthy patient population.3 Thus, it also remains untested whether more intermediate PSADTs predict OS in older, more racially diverse populations with more medical comorbidities and greater competing mortality. We examined the correlation between PSADT and OS among men in the SEARCH database12, a racially diverse cohort treated with RP at multiple VA hospitals nationwide. In a secondary analysis, we examined the correlation between PSADT and PCSM in the same cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical and Pathological Variables

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval from each institution to abstract and combine data, we combined data from patients undergoing RP at the VA Medical Centers in West Los Angeles and Palo Alto, California; Augusta, Georgia; and Durham, North Carolina into the SEARCH database.12 This database includes information on patient age, race, height, weight, clinical stage, cancer grade on diagnostic biopsies, preoperative PSA, surgical specimen pathology (specimen weight, tumor grade, stage, and surgical margin status), and follow-up PSA data. The prostatectomy specimens were sectioned per each institution’s protocol.

Biochemical recurrence (BCR) was defined as a single PSA >0.2 ng/ml, two PSAs equal to 0.2 ng/ml, or secondary treatment for an elevated/rising postoperative PSA. Men receiving adjuvant treatment with an undetectable PSA were censored as not recurred at the time of treatment. PSADT, calculated using the log-slope method,13 was calculated for all patients meeting the recurrence definition who had a minimum of two PSA values, separated by at least three months, within two years after recurrence. All PSAs within the first two years after recurrence were used to calculate PSADT. For patients starting salvage hormone or radiation therapy within this time, only PSAs before salvage therapy were used. Patients with a PSADT ≤0 (i.e., decline/no change) or very long PSADT (>100 months) were assigned a value of 100 months for ease of calculations (n=67). Men who died with metastatic, progressive, castrate-resistant PC were considered to have died of PC.

Study Population

To be included in the study, men had to have recurred and have a calculable PSADT. Of the 2154 men in SEARCH not treated with pre-operative radiation or hormonal therapy, we excluded 46 men without follow-up data, 1406 men who did not recur, 311 men who recurred without calculable PSADT data, 66 men missing pathological or pre-operative PSA data, resulting in a study population of 345.

Statistical Analysis

Our primary goal was to examine the correlation between PSADT and time from recurrence to OS. We divided PSADT into the clinically meaningful and previously described categories of <3, 3–8.9, 9–14.9, and ≥15 months.2 Race, body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), biopsy Gleason (2–6, 7, 8–10), clinical stage (T1 vs. T2/3), pathologic Gleason (2–6, 7, 8–10), surgical margin status, extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and lymph node metastasis were evaluated as categorical variables. Age at surgery, time to recurrence, age at PSA recurrence, preoperative PSA, percentage of positive cores on biopsy, and prostate weight were examined as continuous variables. Due to non-normal distributions, PSA and prostate weight were examined after logarithmic transformation.

We first examined the association between PSADT and OS using the log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier plots. We then performed Cox proportional hazards regression analysis examining the correlation between PSADT and time from recurrence to OS. The variables included in the final model included PSADT (categorized as <3, 3–8.9, 9–14.9 and ≥15 months), age at recurrence, preoperative PSA (logarithmically transformed), year of surgery, pathological Gleason (2–6, 7, 8–10), lymph node metastasis (positive vs. negative vs. not performed), seminal vesicle invasion, extracapsular extension, surgical margin status, and time from surgery to recurrence. In secondary analyses, we also examined the correlation between PSADT and PCSM using the model described above, though few men died of PC (n=16).

P-values <0.05 were considered significant. Data were similar among all sites and were combined for analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 10 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Clinicopathological features

All patients experienced a BCR and had a calculable PSADT. Mean age at surgery was 63.4 years (SD 6.2) (Table 1). The cohort was racially diverse and included 178 (52%) Caucasian men, 142 (41%) African American men, and 25 (7%) men of other races. Among this group of recurrent men, the median PSADT was 14.9 months (IQR 8.1–46.5). When PSADT was stratified as <3, 3–8.9, 9–14.9, and ≥15 months, there were 12 (3%), 84 (24%), 77 (22%), and 172 (49%) men in each category, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and pathologic characteristics of recurrent men with PSADT and overall survival data available within the SEARCH Database (n=345)

| Mean age at surgery ± SD (years) | 63.4 ± 6.2 |

| Median Year of Surgery | 1997 |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 178 (52%) |

| African American | 142 (41%) |

| Other | 25 (7%) |

| BMI | |

| <25 kg/m2 | 77 (27%) |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 130 (46%) |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 78 (27%) |

| PSA (ng/ml) | |

| Mean ± SD | 12.9 ± 11.1 |

| Median (IQR) | 9.7 (6.0–16.3) |

| Biopsy Gleason Sum | |

| 2–6 | 176 (53%) |

| 7 | 115 (34%) |

| 8–10 | 44 (13%) |

| Pathologic Gleason Sum | |

| 2–6 | 98 (28%) |

| 7 | 135 (39%) |

| 8–10 | 112 (32%) |

| Percentage Positive Cores | |

| Mean ± SD | 40.8 ± 24.2 |

| Median (IQR) | 33.3 (20.0–57.1) |

| Prostate Weight (grams) | |

| Mean ± SD | 40.6 ± 17.7 |

| Median (IQR) | 36.9 (28.7–47.5) |

| Extraprostatic Extension | 130 (38%) |

| Positive Surgical Margins | 203 (59%) |

| Seminal Vesicle Invasion | 63 (18%) |

| Clinical Stage | |

| T1a | 1 (0.3%) |

| T1b | 5 (1.6%) |

| T1c | 127 (40.2%) |

| T2 | 21 (6.7%) |

| T2a | 93 (29.4%) |

| T2b | 51 (16.1%) |

| T2c | 16 (5.1%) |

Factors associated with OS

Mean time to recurrence was 32.8 months (SD=33.3), and median was 22.3 months (IQR=6.2–50.1). The mean and median follow-up after recurrence were 85.3 (SD=48.3) and 81.5 months (IQR=45.0–122.8), respectively. During follow-up, 88 patients (26%) patients died, 16 (5%) of whom died of PC. The 5-, 10-, and 15-year OS rates from the time of BCR were 86% (95% CI=81–89%), 67% (95% CI=60–73 %), and 44% (95% CI=31–57%), respectively. The median time to OS after recurrence was 165 months.

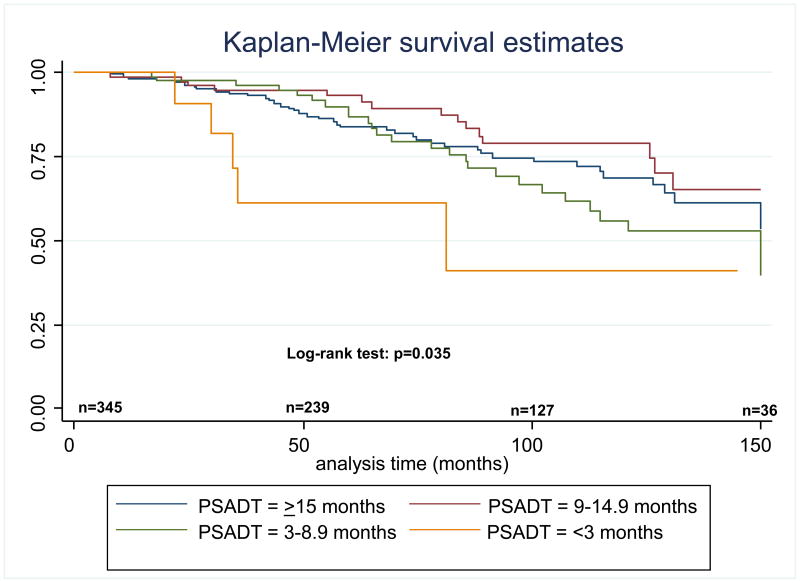

When PSADT was stratified as <3, 3–8.9, 9–14.9, and ≥15 months, in unadjusted analyses, shorter PSADT was significantly associated with worse OS (log-rank, p=0.035) (Figure 1). After multivariate adjustment, PSADT <3 months (versus PSADT ≥15 months) was significantly associated with worse OS (HR=5.48, p=0.002) (Table 2). There was a trend towards an association between a PSADT of 3–8.9 months and worse OS (HR=1.70, p=0.07). Age at recurrence was also significantly associated with worse OS (HR=1.05, p=0.024). No other factors were significantly associated with OS.

Figure 1. Overall survival after RP, stratified by PSADT.

RP: radical prostatectomy; PSADT: PSA doubling time; n: number of patients at risk at the specified time point.

Table 2.

Risk of overall mortality and prostate cancer-specific mortality stratified by PSADT group, relative to PSADT >15 months*

| Overall survival | ||

|---|---|---|

| HR** | p-value | |

| <3 months | 5.48 (1.88–15.95) | 0.002 |

| 3–8.9 months | 1.70 (0.95–3.04) | 0.07 |

| 9–14.9 months | 0.85 (0.45–1.59) | 0.60 |

| Prostate cancer-specific survival | ||

| HR** | p-value | |

| <3 months | 544.34 (26.8–11042.74) | <0.001 |

| 3–8.9 months | 16.31 (2.47–113.26) | 0.004 |

| 9–14.9 months | 2.98 (0.37–23.75) | 0.3 |

PSADT was adjusted for the clinicopathological variables in the final model

95% CI

PSADT and PCSM

In this cohort of recurrent men, 16 (5%) died of PC. Shorter PSADT was significantly associated with a higher risk of PCSM (log-rank, p<0.001). When PSADT was stratified into the categories of <3, 3–8.9, 9–14.9, and ≥15 months, PSADT <3 months (p<0.001) and 3–8.9 months (p=0.004) were both strongly associated with worse PC-specific survival relative to ≥15 months (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Post-RP PSADT is a well-established prognostic variable that has been demonstrated to be associated with PCSM.2–6 However, many of these studies were performed at tertiary care centers and included relatively young and racially homogenous men and only two previous studies have examined the correlation between PSADT and OS.3,6 One study examined the association between PSADT and both OS and PCSM in a more racially diverse cohort, but only examined the mortality risk for very short PSADTs (<3 months vs. ≥3 months) and did not examine the prognostic significance of more intermediate PSADT values.6 Therefore, we examined the association between post-RP PSADT, OS, and PCSM among men in the racially diverse, equal access SEARCH database.

As mentioned above, several studies examined the association between PSADT and PCSM after primary treatment for PC. The first study to examine this was by D’Amico et al. in 2003.6 The authors studied over 8000 men in the combined multi-center CaPSURE and CPDR databases and found a short (i.e., <3 month) PSADT after RP or radiotherapy was positively associated with shorter time to PCSM (HR 19.6, 95% CI 12.5–30.9). This study, however, did not examine the prognostic implication of recurrence with more intermediate PSADTs. Similarly, Albertsen et al, confirmed that men who died of prostate cancer after radiation or RP had a shorter PSADT than men who did not die of their cancer.4 Freedland et al. also examined the correlation between post-RP PSADT and PCSM among men treated at Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH), of whom ~95% were Caucasian.2 They found men with a PSADT <3 months (HR=27.48, 95% CI=10.66–70.85) or 3–8.9 months (HR=8.76, 95% CI=3.74–20.5) were at increased risk of PCSM versus men with a PSADT ≥15 months. These results are in line with our results. We also found, albeit with quite limited numbers (only 16 men died of PC during the follow-up period), that a PSADT of <3 months (p<0.001) and 3–8.9 months (p=0.004) were both strongly associated with PCSM, although the limited number of PC deaths in our study makes assessing the exact risk difficult. Of note, the patients in our study with a PSADT <3 months appeared to have a lower risk of PCSM than men in either the JHH2,3 or CPDR/CapSURE cohorts.6 Whether this reflects the small number of men who died of PC in this study thereby limiting our ability to reliably estimate PCSM or whether it is due to early aggressive secondary treatment in the SEARCH cohort14 warrants further study.

Given that many men with recurrent PC will die of causes unrelated to their disease, it is not clear that PSADT would predict OS just because it predicted PCSM. To examine this issue, JHH group analyzed the association between PSADT and OS in a follow-up study.3 In that study, the same two highest risk PSADT categories were found to be associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (PSADT <3 months: HR=11.46, 95%=CI 5.69–23.09; PSADT 3–8.9 months: HR=4.35, 95%=CI 2.57–7.35). These results are also in line with our results, as we found that recurrence with a PSADT of <3 months after RP was associated with worse OS (HR=5.48, 95% CI=1.88–15.95, p=0.002) and a trend towards worse OS among men with a PSADT of 3–8.9 months (HR=1.70, 95% CI=0.95–3.04, p=0.07). Similarly, D’Amico et al. found that men with a post-RP PSADT <3 months were at an increased risk of all-cause mortality versus men with a PSADT >3 months (p<0.001).6 Of note, the median OS for men with a PSADT <3 months in the current study (82 months) was very similar to the findings from prior studies further demonstrating that recurrences with a PSADT <3 months represent a high-risk group.3,6 Moreover, both the JHH study and the current study found that 9 months seemed to be the cut-point at which PSADT portended an increased risk of overall mortality. This finding is therefore relatively consistent throughout the literature and justifies prior studies using PSADT of <9 months as an end-point predictive of an aggressive recurrence.15,16 It also justifies its use as an entry criterion for clinical trials (e.g., RTOG P0014 and TAX 3503).17

One important corollary from this study is that while many people may assume BCR after RP is more of an “annoyance” than a clinically significant finding potentially influencing overall prognosis, this study redemonstrates this is not true for all men. While it may be true for men with a longer PSADT, those with short PSADTs (<9 months) are at substantial risk of mortality. Therefore, for a select subset of men, BCR is a clinically meaningful event influencing overall prognosis and it is clear that PC deaths impact OS among men who recur after RP.

This is the first study to examine the impact of post-RP PSADT on OS in an all equal-access setting. This cohort of men treated at VA hospitals was racially diverse; only 52% of men were Caucasian with African-American men comprising a large minority (41%). In the JHH study examining PSADT and OS, which has the most similar design to our study, 95% were Caucasian and the remaining 5% were of other races.3 Because African-American race is associated with more aggressive PC18, it is notable similar findings were observed in these cohorts with very different racial compositions. Additionally, the mean age at surgery in this study was 63.4 years – almost four years older than the JHH cohort (59.7 years). Age is clearly associated with increased overall mortality risk in general and among men with BCR as shown in both the current and prior study.3 Thus, the fact PSADT correlated with OS similarly in this study as prior studies of younger men underscores the power of PSADT as a prognostic variable. Another difference between SEARCH and the cohorts examined in prior studies is overall health status. Within SEARCH, at the time of surgery, 19% of men are diabetic19 and 33% are active smokers.20 Because age is associated with an increased comorbidity, it is impressive that PSADT is a powerful predictor of OS and PCSM among this older cohort with a high prevalence of tobacco use and medical comorbidities.

This study has several limitations. The number of men who died of PC was small (n=16). However, given that some men died of unknown causes, it is possible some of these deaths were due to PC. Therefore, while we demonstrated a strong association between PSADT and PCSM, there is a possibility our results were impacted by type I error. However, given the consistency of our findings with previous studies, this is unlikely. Additionally, while it appears men in this cohort had more medical comorbidities than those in other cohorts, we lack details about this and are planning to examine the health status of our subjects at recurrence and the impact of medical comorbidity on PC-related outcomes in future studies. Adjuvant and salvage hormonal and/or radiation therapy may also impact OS after RP. Because we were studying the natural history of all men who underwent surgery, we did not examine the impact that these treatments had on the relationship between PSADT and OS. It is a very interesting question that we hope to answer in future studies once we have more data. Additionally, PCSM and OS are often delayed events; whether our results would change with longer follow-up is unknown.

CONCLUSIONS

Nonetheless, in the SEARCH database, which includes an older, racially diverse cohort, PSADT was a powerful predictor of OS. Men who recurred with a PSADT <3 months are at increased overall mortality risk and those with a PSADT of 3–8.9 months have a borderline increased overall mortality risk. Although the numbers were limited, there was a strong correlation observed between a PSADT <9 months and PCSM. Thus, we redemonstrated that PSADT is a useful tool for identifying men at increased risk of overall and PCSM early in their disease course. These findings validate prior results from tertiary care referral centers regarding the prognostic importance of PSADT.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, National Institutes of Health, the Georgia Cancer Coalition, the AUA Foundation/Astellas Rising Star in Urology Award, and Duke University’s CTSA grant UL1RR024128 (NCRR/NIH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Trapasso JG, deKernion JB, Smith RB, Dorey F. The incidence and significance of detectable levels of serum prostate specific antigen after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 1994;152:1821–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, Eisenberger M, Dorey FJ, Walsh PC, Partin AW. Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2005;294:433–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, Eisenberger M, Dorey FJ, Walsh PC, Partin AW. Death in patients with recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: prostate-specific antigen doubling time subgroups and their associated contributions to all-cause mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1765–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Penson DF, Fine J. Validation of increasing prostate specific antigen as a predictor of prostate cancer death after treatment of localized prostate cancer with surgery or radiation. J Urol. 2004;171:2221–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000124381.93689.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valicenti RK, DeSilvio M, Hanks GE, Porter A, Brereton H, Rosenthal SA, Shipley WU, Sandler HM. Posttreatment prostatic-specific antigen doubling time as a surrogate endpoint for prostate cancer-specific survival: an analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 92–02. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:1064–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Amico AV, Moul JW, Carroll PR, Sun L, Lubeck D, Chen MH. Surrogate end point for prostate cancer-specific mortality after radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1376–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson AJ, Scardino PT, Kattan MW, Pisansky TM, Slawin KM, Klein EA, Anscher MS, Michalski JM, Sandler HM, Lin DW, et al. Predicting the outcome of salvage radiation therapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2035–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacinto AA, Fede AB, Fagundes LA, Salvajoli JV, Castilho MS, Viani GA, Fogaroli RC, Novaes PE, Pellizzon AC, Maia MA, et al. Salvage radiotherapy for biochemical relapse after complete PSA response following radical prostatectomy: outcome and prognostic factors for patients who have never received hormonal therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2007;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee AK, Levy LB, Cheung R, Kuban D. Prostate-specific antigen doubling time predicts clinical outcome and survival in prostate cancer patients treated with combined radiation and hormone therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:456–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward JF, Zincke H, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Blute ML. Prostate specific antigen doubling time subsequent to radical prostatectomy as a prognosticator of outcome following salvage radiotherapy. J Urol. 2004;172:2244–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000145262.34748.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart AJ, Scher HI, Chen MH, McLeod DG, Carroll PR, Moul JW, D’Amico AV. Prostate-specific antigen nadir and cancer-specific mortality following hormonal therapy for prostate-specific antigen failure. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6556–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.20.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton RJ, Aronson WJ, Presti JC, Jr, Terris MK, Kane CJ, Amling CL, Freedland SJ. Race, biochemical disease recurrence, and prostate-specific antigen doubling time after radical prostatectomy: results from the SEARCH database. Cancer. 2007;110:2202–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, Chan DW, Pearson JD, Walsh PC. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 1999;281:1591–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreira DM, Banez LL, Presti JC, Jr, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Kane CJ, Amling CL, Freedland SJ. Predictors of secondary treatment following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: results from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital database. BJU Int. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teeter AE, Banez LL, Presti JC, Jr, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Kane CJ, Amling CL, Freedland SJ. What are the factors associated with short prostate specific antigen doubling time after radical prostatectomy? A report from the SEARCH database group. J Urol. 2008;180:1980–4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.031. discussion 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeck FR, Aronson WJ, Presti JC, Jr, Terris MK, Kane CJ, Amling CL, Freedland SJ. Do nomograms predict aggressive recurrence after radical prostatectomy more accurately than biochemical recurrence alone? BJU Int. 2009;103:603–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.www.clinicaltrials.gov

- 18.Grossfeld GD, Latini DM, Downs T, Lubeck DP, Mehta SS, Carroll PR. Is ethnicity an independent predictor of prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy? J Urol. 2002;168:2510–5. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayachandran J, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Presti JC, Jr, Amling CL, Kane CJ, Freedland SJ. Diabetes and Outcomes after Radical Prostatectomy – Are Results Affected by Obesity and Race? Results from the SEARCH Database Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0777. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreira DM, Antonelli J, Presti JC, Jr, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Amling CL, Kane CJ, Freedland SJ. Association of cigarette smoking with time to biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: Results from the SEARCH Database. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.066. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]