Abstract

When conducting a clinical trial, it is important that clinical investigators successfully meet all research expectations, including regulatory requirements and the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Clinical investigators face challenges during the conduct of clinical trials that are distinctly different from those encountered during the routine practice of medicine. Many of these challenges stem from regulatory requirements, the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the rigorous nature of clinical trials. When conducting a clinical trial, it is important that clinical investigators successfully meet all research expectations.

A clinical investigator's primary responsibility is to conduct research that contributes to generalizable knowledge while protecting the rights and welfare of human participants.1 This article, part of the Journal of Oncology Practice series on attributes of exemplary clinical trial sites,2 discusses select investigator responsibilities and provides practical advice on how to promote compliance in practice.

Conducting Ethical Research

It is important to conduct research in an ethical manner. Investigators must be diligent throughout the conduct of a clinical trial: while designing the protocol, when deciding which trials to conduct, during the performance of the study, and after conclusion of the study (Fig 1). Although there are multiple regulatory safeguards designed to ensure the ethical conduct of research, it is ultimately the investigator's responsibility to make certain that the research is fair and equitable to study participants. When the investigator is also the sponsor of the study, then responsibilities also include protocol design.

Figure 1.

Investigator responsibilities throughout the life of a study. Copyright Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Adapted with permission. IRB, institutional review board; CRF, case report form; AE, adverse event; SAE, severe adverse event.

The 1979 Belmont Report established basic guidelines intended to prevent ethical problems related to research.3 The report outlines three basic principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. Detailed discussion about each of these principles and the differences between clinical practice and research is provided in the report. Additional information about the report and related topics is available, free of charge, through the Web site of the Office for Human Research Protection (OHRP).3

The majority of investigators respect the importance of conducting ethical research, but even the most cognizant investigators may encounter unexpected challenges. For example, an ethical dilemma can arise when the control arm of a trial does not correlate with the standard treatment typically prescribed by the physician. Issues like this need to be discussed during trial design and considered as part of the decision to implement new trials at the site. Clinical investigators need to review the protocol in detail and understand the primary end point of every study they oversee. This practice prevents inadvertent issues that can affect patient safety and/or the scientific integrity of the study. For example, if a study is designed to provide adjuvant treatment to patients, but the investigator is slow to identify the first signs of relapse, then the quality of the science suffers and potentially affects approval of the agent by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Understanding the research protocol and investigator's brochure4 helps to prevent potential issues.

In addition to understanding study-specific requirements, investigators and their teams are encouraged to obtain training that more broadly addresses issues related to the conduct of clinical research. All clinical investigators should have participated in educational opportunities covering International Conference on Harmonization GCP, Human Subject Protection, and requirements for the shipping of biologic specimens. The Society of Clinical Research Associates also offers several training opportunities, including a workshop focused on investigator responsibilities and a course cosponsored by the FDA pertaining to regulatory issues.5 Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research6 and the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative7 are also both reliable sources for education and training. Training may also be offered by study sponsors or your institution.

Informed Consent Process

Informed consent is a process that extends beyond a patient simply signing a consent form. Clinical research requires that individuals be fully informed about the study they are being offered. Throughout the informed consent process, potential research participants should be given the opportunity to learn about the research study and have all their questions answered. According to the Belmont Report,3 individuals must be given the opportunity to make informed choices with regard to how they will be treated and what interventions they will participate in. Potential participants should be informed about the risks; anticipated benefits; and any alternative treatment options they have, including hospice care. An appropriate informed consent process needs to be conducted by a qualified individual who understands the clinical trial protocol and has knowledge about the potential benefits and adverse effects of the therapeutic agent under investigation.

If the investigation is a randomized, controlled clinical trial, research staff should be certain to alert potential participants to the concept of randomization. The potential participant must also be informed about the treatment that will be given to individuals who are randomly assigned to the control arm of the trial. They should be told that neither they nor their provider can control which arm of the trial they are randomized to. Patient-oriented educational materials about clinical trials are available, free of charge, on ASCO's patient education Web site, www.cancer.net.8

The informed consent document is a record of what was discussed during the informed consent process. This document needs to be approved by an institutional review board before the initiation of a study and should be written at a reading level that is appropriate for potential research participants. Whenever possible, individuals interested in enrolling onto a clinical trial should be given a copy of the informed consent document to review at home and discuss with their friends and family. After having ample opportunity to review the informed consent form and consider all of their options, the potential participant should be given another opportunity to ask questions.

It is very important that research participants sign the most current approved version of the informed consent form for the trial they are participating on. Many sites institute “version control” to prevent errors by maintaining an electronic file of informed consent documents and permitting staff to have access only to the most current version of the consent form for each protocol. Maintaining these files electronically ensures that an old version of the informed consent document is not inadvertently used. OHRP provides extensive information about the informed consent process via their Web site and recently produced helpful videos to instruct providers on how to appropriately conduct the informed consent process.9

Statement of Investigator

When conducting clinical research with an investigational agent, such as a drug or biologic, an investigator must comply with all applicable FDA rules and regulations. An investigator must also complete the Statement of Investigator (FDA Form 1572) before participating in an FDA-regulated investigation.10 FDA Form 1572 is a legally binding document designed to inform clinical investigators of their research obligations and secure the investigators' commitment to follow pertinent FDA regulations. By signing this form, the investigator confirms that they will abide by all FDA regulations.

Falsifying information on the FDA Form 1572 can lead to the investigator being disqualified. Moreover, if the investigator's action is determined to be fraudulent in nature, criminal action can be taken, potentially resulting in disbarment of the investigator.11 This underscores the importance of reading and understanding all elements of the form, including the investigator responsibilities explicitly listed in section 9. Individuals who want to learn more about FDA Form 1572 are encouraged to read the FDA guidance document, “Information Sheet Guidance for Sponsors, Clinical Investigators, and IRBs,”12 which provides detailed information about FDA Form 1572 and answers frequently asked questions.

Investigators should be especially mindful to read and understand section 9 of FDA Form 1572. This section lists the commitments the investigator is agreeing to on completion of the form. A principal investigator needs to be certain that all commitments are upheld on every study they are responsible for. Even if certain tasks have been delegated, it is the investigator's responsibility to ensure that all study-related responsibilities are appropriately fulfilled.

One area of frequent inquiry pertains to section 6 of FDA Form 1572, which asks for the names of all subinvestigators who will be assisting with the investigation. According to FDA Regulation 21 CFR 312.3(b), “In the event an investigation is conducted by a team of individuals, the investigator is the responsible leader of the team. ‘Subinvestigator’ includes any other individual member of that team.”13 FDA guidance clarifies that individuals should be listed if they make direct and significant contributions to the data or perform study-related procedures. According to the guidance document, “In general, if an individual is directly involved in the performance of procedures required by the protocol, and the collection of data, that person should be listed on the 1572.”12 The guidance also provides specific examples of the types of individuals who should be listed.

The FDA guidance document also clarifies that everyone listed as either an investigator or subinvestigator must disclose financial interests to the study sponsor. The FDA has a separate guidance document related to financial disclosure, “FDA's Guidance for Industry Financial Disclosure by Clinical Investigators.”14 If the investigation is funded by Public Health Service agencies such as the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [NCI], then the investigator must also comply with Regulation 42 CFR Part 50, Subpart F: “Responsibility of Applicants for Promoting Objectivity in Research for Which PHS Funding Is Sought.”15 The FDA and Public Health Services have several different conflict of interest disclosure requirements, including different disclosure thresholds.

Oversight of Investigational Agents

Investigators are responsible for supervising the proper handling, administration, storage, and destruction of investigational agents (ie, drug accountability). Although these tasks can be delegated to an appropriately qualified individual, the investigator maintains ultimate responsibility. If an investigator delegates this task to a pharmacist or pharmacy technician who is not already dedicated to research, that individual needs to receive training specific to the responsibilities associated with the disposition and use of investigational agents. These responsibilities differ greatly from those associated with standard practice and are important for promoting patient safety and the collection of quality research data.

Oversight begins as soon as the investigational agent is ordered. The individual who receives the shipment needs to document the quantity of the agent that was received on the drug accountability record form (DARF). Beyond completing the standard documentation requirements on the DARF, staff should be aware of any protocol-specific recordkeeping requirements. For example, some agents are shipped with a temperature-monitoring device, requiring that staff record whether the agent was maintained within the proper temperature range throughout shipment. If the monitoring device indicates that the agent was exposed to a temperature outside the range specified by the trial sponsor, then further action may be needed.

After receipt of the agent being used in a clinical trial, the agent needs to be stored in a secure location, at the temperature specified by the sponsor. Stored investigational agents need to be separated according to study protocol. In addition, an individual drug accountability form must be maintained for each agent as well as for each dosage formulation for every protocol. Even if a certain agent is also used in standard practice or on more than one research protocol, the drug supply for each clinical trial must be kept separate and accounted for on an individual accountability form.16 Careful recording of the preparation and use of the investigational agent must also be maintained. Documentation is needed regarding which individual calculated the dose to be administered, prepared the agent for use, and administered the agent; all verifications that occurred throughout the process should also be documented. The amount of agent that is dispensed from the supply needs to be recorded on the DARF, and any agent that remains after completion of the trial should be shipped back to the trial sponsor or destroyed.

An investigator should also be aware of any specific requirements mandated by the trial sponsor. The Investigator Handbook published by NCI is a helpful reference for investigators conducting NCI-funded trials.16 The Clinical Trials Support Unit is also a helpful resource for individuals conducting NCI-sponsored phase III clinical trials.17

Drug accountability not only ensures safe and proper use of investigational agents but also is an important component of audits conducted by the FDA and/or sponsor. Staff education is important in helping staff understand the special requirements associated with agents used on clinical trials. Routine internal audits are a helpful way to verify that investigational agents are being appropriately maintained and that documentation is accurate. Facilitating good communication between the pharmacy staff and research team helps to ensure proper oversight of investigational agents.

Reporting Adverse Events

It is required to document all adverse events that occur during the course of the clinical investigation. Keeping a log of adverse events is a helpful organizational tool, and such logs should be reviewed during regularly scheduled research team meetings. It is important that a principle investigator be aware of adverse events because the event may trigger the need for a dose adjustment. Serious or unanticipated events should be addressed immediately and may require meeting outside regularly scheduled team meetings.

Serious, unanticipated adverse events need be reported to both the institutional review board and sponsor within a short timeframe. It is advisable that a research site develop a standard operating procedure (SOP) to help maintain consistent adverse event reporting. SOPs are not required in any federal regulations, but they are very helpful in maintaining consistent processes at the site and are a useful resource when training new research staff. An SOP is also a helpful reference when determining which events need to be reported. The OHRP and FDA both have developed helpful guidance documents for adverse event reporting.18,19 These guidance documents explain the regulations associated with reporting adverse events and are an important reference when a research site is developing or updating their SOP for adverse event reporting.

Maintaining Accurate Records

The importance of maintaining accurate records when conducting clinical research cannot be overstated. It is important that all collected data match information found in source documents, such as a pathology report or the patient's medical record. In addition, issues such as protocol deviations must be well documented. A situation that occurs today may not be reviewed or questioned until months or years in the future. It is nearly impossible to recall particular study conduct events during an audit unless they have been well documented.

When a protocol deviation occurs, the site should document the event on a deviation log and develop a corrective action plan that clearly describes how similar events will be prevented in the future. This corrective action plan then becomes a source document. Research staff might also use this corrective action plan to guide the development of a new SOP that will help prevent similar deviations in the future.

As with many investigator responsibilities, an investigator is permitted to delegate tasks associated with data collection and documentation to a qualified individual. However, it is important that the investigator know that this individual will appropriately conduct the tasks being delegated. One way to ensure clear communication between an investigator and staff is to use a delegation log, which is a signed record of which study tasks have been assigned to which individual. It is important that the investigator be available to staff to answer questions and make decisions.

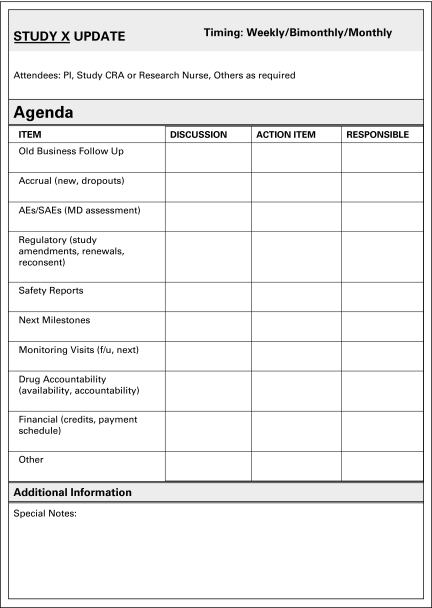

Holding routine meetings between the investigator and staff is an important way to ensure effective communication among study team members. Staff can use these meetings as an opportunity to raise concerns and document any action that was taken in response to those concerns. The frequency of the meetings may vary on the basis of trial complexity and the number of individuals enrolling onto the trial. To ensure the most efficient use of in-person meetings, the research team should develop a meeting agenda. Such agendas can vary depending on the needs of the site. For example, some sites prepare the agenda on the basis of items that have been delegated to the staff (Fig 2). Other sites prefer to use their patient list to structure the agenda. These sites may keep a table listing every patient enrolled or considering participation, then update the chart with related action items. Regardless of the structure, routine meetings are a good opportunity for the investigator to review and sign off on any documentation such as adverse events that are not serious or unanticipated (serious, unanticipated adverse events must be addressed immediately at the time of the event). All updates or action items should be recorded on meeting minutes and then signed by the investigator.

Figure 2.

Research team meeting agenda. Copyright Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Adapted with permission.

To help with organization, research sites often use electronic systems to maintain research documents. Some sites find it helpful to develop a shared drive that is organized identically across all studies. Because study documents (ie, budget documents, notes to file, and consent forms) are all saved in a consistent format across studies, this type of organization makes it easy to cross-train staff and promotes a seamless transition when staff turnover occurs.

Summary

When it comes to the conduct of clinical research, an investigator has numerous responsibilities. Because of the magnitude of this topic, we were unable to address all investigator responsibilities within the context of this article, but we hope the reader will access the external resources that were referenced for additional information. We also encourage the reader to pursue clinical investigator training to better understand the full totality of their responsibilities as an investigator.

ASCO Statement on Minimum Standards and Exemplary Attributes of Clinical Trial Sites

The ASCO statement addresses the minimum requirements for sites conducting quality clinical trials as well as the attributes of exemplary sites. Both minimum requirements and exemplary attributes were based on a review of the literature, current regulatory requirements, and consensus among community and academic clinical researchers. In order to conduct quality clinical research, sites should meet the minimum requirements. It should be noted, however, that the exemplary attributes are voluntary and suggested as goals, not requirements. Not all attributes will apply to all clinical trial sites, and many sites may be able to conduct high-quality clinical trials without accomplishing all attributes.

Feedback Request

Suggest future topic ideas for the series and provide your feedback by sending an e-mail to researchresources@asco.org.

Acknowledgment

The information contained in this article is general in nature. It is not intended to be, and should not be construed as, legal advice relating to any particular situation.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: None Stock Ownership: Chris David Beardmore, Translational Research Management Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Allison R. Baer, Susan Devine, Chris David Beardmore, Robert Catalano

Administrative support: Allison R. Baer

Collection and assembly of data: Allison R. Baer, Susan Devine, Chris David Beardmore, Robert Catalano

Data analysis and interpretation: Allison R. Baer, Susan Devine, Chris David Beardmore, Robert Catalano

Manuscript writing: Allison R. Baer, Susan Devine, Chris David Beardmore, Robert Catalano

Final approval of manuscript: Allison R. Baer, Susan Devine, Chris David Beardmore, Robert Catalano

References

- 1.International Conference on Harmonisation, Good Clinical Practice (ICH GCP). 1.34 Investigator. http://ichgcp.net/?page_id=377.

- 2.Zon R, Meropol N, Catalano R, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement on minimum standards and exemplary attributes of clinical trial sites. J Clin Oncol. 2008:2562–2567. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Human Subjects Research. Belmont Report. Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/belmont.html.

- 4.International Conference on Harmonization, Good Clinical Practice (ICH GCP). 1.36 investigator's brochure. http://ichgcp.net/?page_id=381.

- 5.Society of Clinical Research Associates. Education. http://www.socra.org/html/education.htm.

- 6.Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research. Education. http://www.primr.org/Education.aspx?id=34&linkidentifier=id&itemid=34.

- 7.Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative. http://www.citiprogram.org/Default.asp.

- 8.Cancer.Net.Clinical Trials. www.cancer.net/clinicaltrials.

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services. USGOVHHS. http://www.youtube.com/user/USGOVHHS#g/c/5965CB14C2506914. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. Statement of investigator (Title 21, Code of Federal Regulations Part 312) http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/ReportsManualsForms/Forms/UCM074728.pdf.

- 11.US Food and Drug Administration. FAQs on debarments/disqualifications: Questions and answers on debarments and disqualifications. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm176043.htm.

- 12.US Food and Drug Administration. Information Sheet Guidance For Sponsors, Clinical Investigators, and IRBs. Frequently Asked Questions—Statement of Investigator (Form FDA 1572) http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM214282.pdf.

- 13.US Food and Drug Administration. Investigational New Drug Application, Code of Federal Regulations, 21CFR312.3. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=312.3.

- 14.US Food and Drug Administration. Financial Disclosure by Clinical Investigators. Guidance for Industry - Financial Disclosure by Clinical Investigators. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm126832.htm.

- 15.National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. Title 42: Public Health. Part 50—Policies of General Applicability, Subpart F—Responsibility of Applicants for Promoting Objectivity in Research for Which PHS Funding Is Sought. http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&sid=4f72164d081005208534c21a08d7dde1&rgn=div6&view=text&node=42:1.0.1.4.22.6&idno=42. [PubMed]

- 16.National Cancer Institute, Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Investigator's Handbook. A Manual for Participants in Clinical Trials of Investigational Agents Sponsored by DCTD, NCI. http://ctep.cancer.gov/investigatorResources/investigators_handbook.htm.

- 17.Cancer Trials Support Unit. About the CTSU. http://www.ctsu.org.

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Human Research Protections. Guidance on Reviewing and Reporting Unanticipated Problems Involving Risks to Subjects or Others and Adverse Events. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/advevntguid.html.

- 19.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Clinical Investigators, Sponsors, and IRBs. Adverse Event Reporting to IRBs—Improving Human Subject Protection. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM126572.pdf.