Abstract

Gating transitions in the KV4.3 N-terminal deletion mutant Δ2–39 were characterized in the absence and presence of KChIP2b. We particularly focused on gating characteristics of macroscopic (open state) versus closed state inactivation (CSI) and recovery. In the absence of KChIP2b Δ2–39 did not significantly alter the steady-state activation “a4” relationship or general CSI characteristics, but it did slow the kinetics of deactivation, macroscopic inactivation and macroscopic recovery. Recovery kinetics (for both WT KV4.3 and Δ2–39) were complicated and displayed sigmoidicity, a process which was enhanced by Δ2–39. Deletion of the proximal N-terminal domain therefore appeared to specifically slow mechanisms involved in regulating gating transitions occurring after the channel open state(s) had been reached. In the presence of KChIP2b Δ2–39 recovery kinetics (from both macroscopic and CSI) were accelerated, with an apparent reduction in initial sigmoidicity. Hyperpolarizing shifts in both “a4” and isochronal inactivation “i” were also produced. KChIP2b-mediated remodeling of KV4.3 gating transitions was therefore not obligatorily dependent upon an intact N-terminus. To account for these effects we propose that KChIP2 regulatory domains exist in KV4.3 α subunit regions outside of the proximal N-terminal. In addition to regulating macroscopic inactivation, we also propose that the KV4.3 N-terminus may act as a novel regulator of deactivation-recovery coupling.

Key words: KV4 channels, N-terminal domain, N-type inactivation, macroscopic inactivation and recovery, closed state inactivation and recovery, KChIP2 isoforms

Introduction

KV4 channel α subunits, in association with various ancillary β subunits, generate rapidly recovering transient outward potassium current phenotypes designated “Ito, fast” in cardiac myocytes and “IA” in neurons.1–11 In the heart, Ito, fast (mediated by either KV4.2 or 4.3) regulates early repolarization and excitation-contraction coupling in atrial and ventricular myocytes.1–3 In the nervous system, KV4.2- and 4.3-mediated IA phenotypes are involved in several functions, including subthreshold regulation of somal action potentials, somatodendritic interactions, synaptic firing frequency, long term potentiation and pain perception and associated plasticity.4–11 Determination of mechanisms underlying KV4 channel gating thus has important implications for diverse physiological processes regulated by the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

KV1.4, a member of the Shaker (KV1) channel family, generates an inactivating current phenotype that superficially resembles currents mediated by KV4 α subunits.2,12 Classic studies conducted on Shaker13–17 originally identified two inactivation mechanisms, rapid N-type (proximal N-terminal mediated) and slower C-type (conduction pore vestibule closure). Since these classic studies, extensive investigations of these two inactivation mechanisms in Shaker have yielded the following conclusions: (i) N- and C-type inactivation occur predominantly from the open state, i.e., there is no significant closed state inactivation; (ii) N-type inactivation lacks inherent voltage-sensitivity; (iii) N- and C-type mechanisms are coupled, with development of N-type promoting accelerated C-type; and (iv) Recovery from inactivation is governed by the C-type process.18–29

In contrast to Shaker, mechanisms underlying inactivation in KV4 channels are presently unresolved. Nonetheless, there is general consensus2,4,5,7 that many characteristics of KV4 inactivation and recovery appear to be either contrary to or incompatible with predictions of the “conventional” Shaker-gating model. In particular, KV4 channels: (i) Display significant voltage-dependent closed state inactivation (CSI) (reviewed in refs. 2, 5 and 7); (ii) Are distinctly regulated by [K+]o, with increases in [K+]o accelerating macroscopic (open state) inactivation and slowing recovery;30,31 and (iii) Are significantly modulated by KChIPs K Channel Interacting Proteins, see below);2,3,7,8 CSI is likely a primary characteristic for distinguishing between properties of KV4 and Shaker channels. Many physiologically relevant manipulations that alter KV4 gating (including changes in [K+]o,30,31 phosphorylation32 and KChIP isoform coexpression2,3) appear to do so via mechanisms regulating CSI.

In contrast to Shaker, the role(s) of the proximal N-terminal domain in regulating KV4 channel gating transitions remains unclear. Under basal conditions, it was reported that both the N-terminal deletion mutants KV4.1 Δ2–7133 and KV4.2 Δ2–4034 slightly slowed but did not eliminate rapid macroscopic inactivation. These results suggested that the KV4 N-terminal did not act as a conventional N-type “inactivation peptide”. KV4.2 Δ2–40 was also reported to have no significant effects on the kinetics of recovery from either macroscopic inactivation or CSI.34 However, subsequent studies on chimaeric channel constructs provided evidence that the KV4 N-terminal domain could bestow rapid inactivation to KV1.4 channels that had their native N-terminals deleted35 and slowly inactivating KV1.5 and KV2.1 channels.36 These results35,36 suggested that the KV4 N-terminal could act as an N-type-like inactivation peptide under specific non-native conditions. Extending their chimaeric results to KV4.2, Gebauer et al.,36 employed double mutant cycle analysis to determine effects of mutants introduced into the KV4.2 N-terminal domain, inner S6 domain or both. It was concluded36 that KV4.2 possessed an N-type inactivation mechanism, although with energetic and structural characteristics distinct from those in Shaker. Nonetheless, in a subsequent study Barghaan et al.37 concluded that N-type inactivation plays only a minimal role in KV4.2 gating. Rather, the first ∼10 amino acids of the N-terminal were proposed37 to be involved in regulation of “inactivation-deactivation” coupling.

KChIPs are cytosolic regulatory proteins originally identified through interactions with KV4 channels.38,39 While four KChIP genes have been characterized in neural tissue, in heart only KChIP2 isoforms are expressed.2,3 Upon binding to KV4 channels, in general KChIPs increase cell surface expression, moderately slow macroscopic inactivation and significantly accelerate recovery from macroscopic inactivation.2,3 While mechanisms underlying these effects are unresolved, KChIP binding sites have been found in the KV4 N-terminus3,35,38,40,41 In previous KV4.2 Δ2–40 N-terminal deletion studies it was emphasized that functional interactions with KChIP2 isoforms were not present, thus arguing for obligatory involvement of the N-terminal proximal domain.36,37,42 However, several studies have provided evidence for KChIP binding sites located in additional KV4 channel domains. Crystallographic studies40,41 have shown that a single KChIP1 molecule can simultaneously bind to the isolated KV4.3 proximal N-terminal domain of one subunit and the tetramerization (T1) domain of an adjacent subunit. While such crystal structures are informative, it is important to note that they were obtained in the absence of both membrane potential and other channel components. In this regard, prior evidence has been presented for different voltage-dependent conformations of the KV4.2 T1 domain,43,44 presumably mediated via allosteric coupling to other transmembrane domains. It is thus possible that KChIPs may undergo subtle use- and/or state-dependent interactions with KV4 channel domains that would not be detected in crystallographic studies. Prior evidence has also been presented45,46 for putative KChIP binding sites existing in KV4.2 C-terminal domains (see Discussion).

In summary, while there is consensus that KV4 channels display apparently “non-Shaker-like” characteristics,2,4,5,7 evaluation of the present KV4 literature leads to an unclear picture on the role(s) of the proximal N-terminal in regulating these effects. A similar situation exists regarding the role(s) of the N-terminal in KChIP-mediated effects. To begin reassessment of these issues, we used Xenopus oocytes and two-microelectrode voltage clamp to analyze effects of the KV4.3 N-terminal deletion mutant Δ2–39 under basal conditions and in the presence of KChIP2b.2,31,47–49 Emphasis was placed upon characterizing effects of Δ2–39 on macroscopic (open state) versus CSI and recovery. In accord with some prior KV4.2 studies,35,36 our Δ2–39 results provide evidence suggestive of an N-type-like inactivation mechanism existing in KV4.3. However, we also present novel results not predicted from other prior KV4.2 studies (reviewed in refs. 34 and 42). These additional results indicate that the KV4.3 proximal N-terminal is involved in regulating not only deactivation34 but also recovery from macroscopic inactivation and that KChIP2b can exert regulatory effects on KV4.3 gating in the absence of an intact N-terminus.42 Based upon these unexpected34,42 findings, we make two proposals: (i) In addition to modulating macroscopic inactivation, the proximal KV4.3 N-terminal acts as a regulator of deactivation-recovery coupling; and (ii) Additional KChIP2b interaction sites may exist in regions outside of the KV4.3 N-terminal domain.

We acknowledge that in addition to KChIPs several additional ancillary β subunits may also be potential physiologically relevant modulators of KV4 channels.3,8,50–62 However, for reasons to be addressed in Discussion, our coexpression studies focused exclusively on KChIP2b.

Results

Initial observations.

In initial measurements, it was observed that KV4.3 Δ2–39 cRNA resulted in peak current amplitudes ∼10- to 50-fold greater than corresponding wild-type (WT) cRNA currents. To overcome resulting voltage clamp failure, two distinct strategies were employed: (i) Reduction in the amount of Δ2–39 cRNA injected; and/or (ii) Current recording during the first ∼12–24 hours after injection. Employing such approaches, Δ2–39 current amplitudes in the ∼1-5 µA range at +50 mV were routinely recorded. Under these conditions, Δ2–39 moderately slowed macroscopic inactivation (Fig. 1A), a general result consistent with previous observations on KV4.2 Δ2–40.34 All subsequent Δ2–39 measurements were therefore conducted under such “reduced amplitude” conditions and focused on characterizing how N-terminal truncation altered KV4.3 voltage-sensitive gating transitions under basal conditions,34 and whether such effects were capable of being modulated by KChIP2b.42

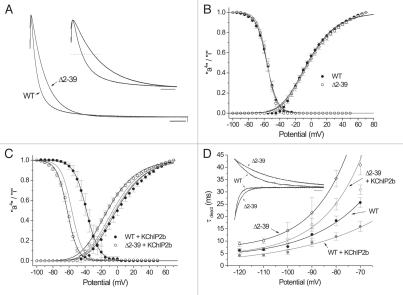

Figure 1.

(A) Representative recordings of WT and “reduced amplitude” Δ2–39 currents elicited (HP = −100 mV) during a 2-s pulse to +50 mV, basal conditions. Peak transient current (peak current minus residual current at t = 2 s) amplitudes normalized (original peak current amplitudes: WT, 2121 nA; Δ2–39, 1428 nA). Calibration bar: 200 ms. Inset: Same currents on an expanded time scale. Dashed line, 50% peak current amplitude. Calibration bar: 100 ms. (B, C) Mean steady state activation “a4” and isochronal (1 sec) inactivation “i” relationships of WT (solid circles) and Δ2–39 (hollow circles) under (B) basal conditions (WT n = 20, Δ2–39 n = 17) and (C) + KChIP2b (“a4”: WT n = 15, Δ2–39 n = 24; “i”: WT n= 6, Δ2–39 n = 8). Mean “a4” data points fit to single Boltzmann relationships raised to the fourth power, mean “i” data points fit to single Boltzmann relationships. Fitting parameters summarized in Table 1. Solid gray curves in C) are corresponding fits of WT and Δ2–39 obtained under basal conditions as per (B). (D) Deactivation kinetics. Main panel: Mean (basal: WT n = 19, Δ2–39 n = 7; + KChIP2b: WT n = 13; Δ2–39 n= 11) τdeact − Vm curves over the potential range −120 to −70 mV. Mean data points obtained from single exponential fits of deactivating tail currents. Basal black, + KChIP2b gray. Solid curves are single exponential fits to mean τdeact data points [basal: WT e-fold change per 21.7 mV, Δ2–39 (fit from −120 to −80 mV) e-fold change per 15.0 mV; + KChIP2b: WT e-fold change per 33.8 mV, Δ2–39 (fit from −120 to −80 mV) e-fold change per 16.6 mV">basal: WT e-fold change per 21.7 mV, Δ2–39 (fit from −120 to −80 mV) e-fold change per 15.0 mV; + KChIP2b: WT e-fold change per 33.8 mV, Δ2–39 (fit from −120 to −80 mV) e-fold change per 16.6 mV]. Inset, Representative overlays of WT and Δ2–39 deactivating tail currents at −60 mV and −120 mV, basal conditions. Isochronal peak currents normalized for comparison and fit with single exponentials with following τdeact values: −60 mV: WT, 24 ms; Δ2–39, 46 ms; α120 mV, WT, 4.4 ms; Δ2–39, 7.1 msec. Calibration bar: 10 ms.

Steady-state activation “a4” and isochronal (1 sec) inactivation (“i”) relationships.

Consistent with previous KV4.2 Δ2–40 studies,34 under basal conditions Δ2–39 produced no significant alterations in either KV4.3 “a4” or “i” relationships (Fig. 1B; quantitative details summarized in Table 1). N-terminal truncation therefore did not alter the relative stabilities of either KV4.3 open state(s) or inactivated closed states. However, in contrast to general predictions of prior KV4.2 Δ2–40 studies,42 KChIP2b could alter one or both KV4.3 gating relationships depending upon whether an intact N-terminal was present. For WT + KChIP2b, “a4” was virtually unaltered yet “i” was depolarized, the latter effect indicating destabilization of inactivated closed states.42,49 In contrast, for Δ2–39 + KChIP2b both “a4” and “i” were hyperpolarized (Fig. 1C and Table 1), indicating stabilization of both open state(s) and inactivated closed states. KChIP2b thus exerted effects on KV4.3 “a4” and “i” in the absence of an intact N-terminal, although these effects were altered compared to those exerted on the WT channel.

Table 1.

Mean fitting parameters of “a4” and “i”

| Conditions | Activation “a4” | Inactivation“i” | ||

| V½ (mV) | k (mV) | V½ | (mV) k (mV) | |

| Basal: | ||||

| WT | −42.9 | 22.5 (n = 20) | −56.6 | 6.7 (n = 11) |

| Δ2–39 | −40.9 | 22.9 (n = 17) | −56.3 | 5.8 (n = 9) |

| +KChIP2b: | ||||

| WT | −38.5 | 22.4 (n = 15) | −38.4 | 7.73 (n = 6) |

| Δ2–39 | −49.5 | 22.5 (n = 24) | −62.3 | 6.5 (n = 8) |

Mean fitting parameters derived for activation “a4” (fourth order Boltzmann relationships) and isochronal (1 second) inactivation “i” (first order Boltzmann relationships) (see Methods for further details) recorded under both basal conditions and in the presence of KChIP2b V1/2, half maximal potential (mV); k, slope factor (mV).

Kinetics of deactivation.

Consistent with prior observations on KV4.2 Δ2–40,34 under basal conditions Δ2–39 slowed KV4.3 deactivation kinetics (fit as single exponentials; Fig. 1D, inset) at all potentials analyzed. Over the most hyperpolarized range of potentials the mean τdeact − Vm curves could be fit as single exponential functions (Fig. 1D, main panel). Therefore, in contrast to minimal effects on “a4”, N-terminal truncation stabilized the channel after the final open state(s) had been entered.34 In contrast, in the presence of KChIP2b deactivation kinetics of both WT and Δ2–39 were accelerated, effects consistent with destabilization of the final open state(s). These latter effects were not predicted from prior KV4.2 Δ2–40 studies.42 N-terminal truncation and KChIP2b coexpression therefore produced opposite effects on KV4.3 deactivation and KChIP2b was able to accelerate deactivation in the absence of an intact N-terminal, albeit to greater extent in the native channel.

Kinetics of macroscopic inactivation.

Isochronal “i” measurements were conducted using 1 s P1 pulses.63–66 While the majority of currents elicited at +50 mV displayed very close or virtually complete inactivation by 1 second, it was possible that this may not have been the case at more hyperpolarized P1 potentials. Restricting fits to 1 s pulses may also have failed to detect and/or characterize adequately multiple components of inactivation. To partially address this complication, kinetics at +50 mV for identical combined P1 + P2 pulses [2 seconds total duration at +50 mV obtained during measurements of isochronal (1 sec) “i” relationships; see Materials and Methods] were analyzed.

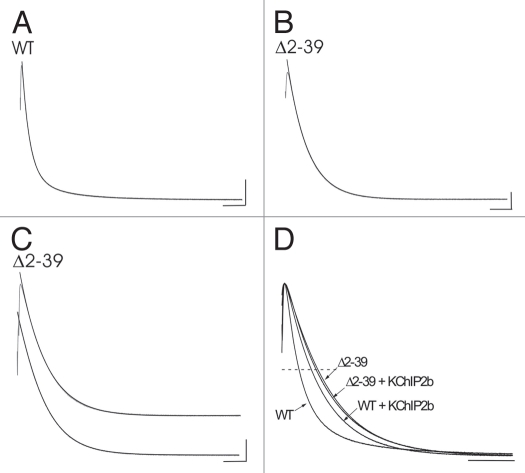

Prior KV4 channel studies supporting both double (reviewed in refs. 31, 49, 63 and 64) and triple exponential (reviewed in refs. 7 and 34) inactivation kinetics have been reported. We thus decided to provide the simplest kinetic description that the majority of our measurements supported. Under basal conditions, WT inactivation could be described as a double exponential process (Fig. 2A). In the majority of cases (n = 10/18) subsequent attempts to fit to a triple exponential function failed to yield acceptable results (see Materials and Methods). As such, only the major double exponential time constants derived from all measurements are summarized in Table 2. On average, the fast component accounted for ∼80% of the WT macroscopic inactivation process and displayed a mean time constant (τfast) ∼6 times faster than that of the slow component (τslow). In contrast to WT, macroscopic inactivation of Δ2–39 could be described as a single exponential process. In the majority of cases (n = 15/22) attempts to fit two exponential components failed to give acceptable results (Fig. 2B). Where acceptable double exponential fits could be derived (Fig. 2C), mean values of the time constants differed by only ∼1.8-fold (Table 2). In summary, under basal conditions Δ2–39 slowed and “remodeled” macroscopic inactivation kinetics at +50 mV such that single exponential behavior became dominant.

Figure 2.

Macroscopic inactivation kinetics at +50 mV (total 2 s pulse from combined and identical 1 second P1 and P2 pulses to +50 mV). Currents gray, fits black. (A) WT, basal conditions, representative double exponential fit with τfast = 67 ms, τslow = 328 ms, and Afast = 0.817. Calibration bar: 500 nA, 200 ms. (B) Δ2–39, basal conditions, representative single exponential fit with τ = 179 ms that failed to acceptably converge to a double exponential fit (double exponential fit parameters [not illustrated]: τfast = 180.4 ms, τslow = 1327 ms, Afast = 0.999). Calibration bar: 200 nA, 200 ms. (C) Δ2–39, basal conditions, representative comparison of single exponential (upper trace; τ = 238 ms) and double exponential (lower trace; τfast = 112 ms, τslow = 203 ms, and Afast = 0.193) fits observed in the minority of cases (n = 7/22) where acceptable double exponential fits were also derived. Calibration bar: 500 nA, 200 ms. (D) Comparative net macroscopic inactivation kinetics at +50 mV. Representative overlays of normalized peak currents for WT, WT + KChIP2b, Δ2–39, and Δ2–39 + KChIP2b. Dashed line, 50% normalized peak current amplitude. Calibration bar: 200 ms.

Table 2.

Mean macroscopic inactivation kinetics at +50 mV, 2 s total pulse duration

| Condition | Single τ(ms) | τfast (ms) | τslow (ms) | Relative Afast | t½ (ms) |

| WT (n = 19) | − | 60.8 ± 4.3 | 359.1 ± 41.3 | 0.801 ± 0.017 | 74.4 ± 4.6 |

| WT + KChIP2b (n = 14) | 153.8 ± 9.0 | 121.6 ± 25.9 (n = 5/14) | 222.7 ± 80.8 | 0.362 ± 0.070 | 131.8 ± 7.6 |

| Δ2–39 (n = 22) | 197.3 ± 9.3 | 115.8 ± 17.0 (n = 7/22) | 207.2 ± 27.4 | 0.252 ± 0.094 | 171.3 ± 7.4 |

| Δ2–39 + KChIP2b (n = 12) | 194.8 ± 10.0 | 105.8 ± 19.2 (n = 7/12) | 180.2 ± 21.2 | 0.190 ± 0.03 | 165.5 ± 10.0 |

Double exponential fits: single τ, mean time constants obtained from single exponential fits; τfast and τslow, fast and slow time constants obtained from acceptable double exponential fits; relative Afast, initial relative amplitude of the fast inactivation component; and t1/2, time for peak current to decline to half original value.

Due to these kinetic differences between WT and Δ2–39, to provide relative measurement of the rate of macroscopic inactivation independent of the assumed number of exponential components the time required for the peak current to decline to half value (t1/2) (Fig. 1A, inset) was directly measured (summarized in Table 2). Based upon mean t½ values, under basal conditions Δ2–39 produced ∼2.3-fold slowing of macroscopic inactivation compared to WT.

In the presence of KChIP2b, WT macroscopic inactivation kinetics were slowed and well described as a single exponential process. In the majority of cases (n = 9/14) fits to double exponentials failed to produce acceptable values. In cases where double exponential fits were obtained there was less than a two.fold difference between mean values of τfast and τslow (Table 2). Comparable results were also obtained for Δ2–39 + KChIP2b (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the single exponential τ values between Δ2–39 and Δ2–39 + KChIP2b. In summary, using mean t½ values as a defining criterion (Table 2), KChIP2b slowed WT mean macroscopic inactivation by ∼1.8.fold. While macroscopic inactivation of Δ2–39 + KChIP2b was significantly slower (∼2.2-fold) than WT, its mean t½ was not significantly different from that of Δ2–39 alone. These effects are qualitatively illustrated in Figure 2D.

Recovery from macroscopic inactivation.

Under basal conditions, the kinetics of recovery from macroscopic inactivation (developed during a 1 s P1 pulse to +50 mV) were measured over the holding potential range of HP = −100 to −70 mV. In general, both WT and Δ2–39 recovery kinetics were slowed upon depolarization (Fig. 3A and B). However, details of the mean recovery waveforms were distinct.

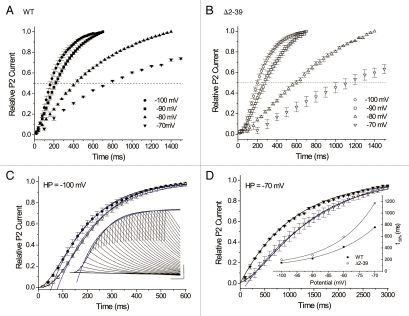

Figure 3.

Kinetics of recovery from macroscopic inactivation developed during a 1 second pulse to +50 mV, basal conditions. (A and B) Mean macroscopic recovery waveforms measured at HP = −100 mV to −70 mV for A) WT (n = 4–6) and B) Δ2–39 (n = 4–6). Dashed straight lines, 5o% relative P2 peak current amplitudes (see text). (C and D) Main panels: fits to WT (solid symbols) and Δ2–39 (hollow symbols) mean macroscopic recovery waveforms at C) HP = −100 mV and D) HP = −70 mV. C) HP = −100 mV: Black curves, sigmoidal fits using all mean data points. WT, “a2” fit, τ = 136 ms; Δ2–39, “a3” fit, τ = 127 ms. Blue curves, truncated single exponential fits beginning at initial times Δt. WT (Δt = 60 ms), τ = 178 ms; Δ2–39 (Δt = 100 ms), τ = 188 ms. D) HP = −70 mV: WT, black curve, single exponential fit using all data points, τ = 1,075 ms; Δ2–39, sigmoidal “a2” fit, τ = 990 ms. Blue curve, Δ2–39 truncated single exponential fit (Δt = 400 ms), τ = 1,733 ms. Insets: (C) Representative Δ2–39 macroscopic recovery waveform at HP = −100 mV. Black curve, sigmoidal “a3” fit, τ = 114 ms. Blue curve, single exponential fit (Δt = 120 ms), τ = 163 ms. Calibration bars: 1 µA, 100 ms. D) Potential dependence of mean times t50% for half macroscopic recovery of WT (solid circles) and Δ2–39 (hollow circles). Extrapolated t50% values determined by linear regression between the two immediate data points with mean values “above” and “below” 0.5 as per (A and B). Solid curves, single exponential fits with e-fold change in t50% per mV as follows: WT, 15.0 mV; Δ2–39, 12.5 mV.

For WT, at the most hyperpolarized HPs (−100 and −90 mV) there was a brief apparent sigmoidicity in recovery (over the first ∼20–40 ms), while Δ2–39 displayed markedly enhanced sigmoidicity (over the first ∼60–100 ms; Fig. 3C, inset). Mean recovery waveforms at HP = −100 mV for WT and Δ2–39 are overlaid in Figure 3C. Both waveforms could be described empirically using sigmoid exponential functions. When early data points were excluded and fits constrained to begin at later times (WT, Δt = 60 ms; Δ2–39, Δt = 100 ms), “conventional” single exponential fits34 could also be derived (blue curves). Beginning at relative P2 values of ∼0.2, such constrained exponential fits overlaid the corresponding sigmoid fits. However, such exponential fits failed to adequately describe the excluded mean data points at earlier times, particularly for Δ2–39.

At the more depolarized HPs (−80 and −70 mV), WT sigmoidicity became minimal to apparently absent, while Δ2–39 sigmoidicity remained. Mean recovery waveforms at HP = −70 mV for WT and Δ2–39 are overlaid in Figure 3D. Recovery of WT could be reasonably described as a single exponential process. Although Δ2–39 recovery was empirically described by a sigmoid function (black curve), constraining a single exponential function to begin at Δt = 400 ms again resulted in an overall curve fit that closely resembled the sigmoid function with the exception of the earliest time points.

Due to the relative complexity of macroscopic recovery kinetics observed under basal conditions, for further comparison the times for 50% peak recovery were extrapolated from each mean recovery curve and plotted as a function of holding potential (Fig. 3D, inset). Both WT and Δ2–39 mean t50% − Vm curves could be described by single exponential functions. Although there were apparent differences in respective voltage sensitivities between the mean t50% − Vm curves, at each fixed HP mean WT t50% values were always less (i.e., more rapid) than those of Δ2–39. In summary, under basal conditions Δ2–39 produced net slowing of macroscopic recovery at each HP. These results are in contrast to KV4.2 Δ2–40 studies, which reported that N-terminal truncation produced no significant effects on the kinetics of recovery from macroscopic inactivation.34

In the presence of KChIP2b, macroscopic recovery (measured at HP = −100 mV) of both WT and Δ2–39 was significantly accelerated (Fig. 4). While WT + KChIP2b recovered most rapidly, Δ2–39 + KChIP2b recovered significantly faster than WT alone. KChIP2b also appeared to lessen the extent of sigmoidicity in the initial recovery process. This effect was particularly prominent for WT + KChIP2b, the overall recovery waveform being well approximated by a single exponential that extrapolated to within ∼10 ms of initial Δt = 0 ms. While recovery of Δ2–39 + KChIP2b displayed a reduced degree of sigmoidicity compared to basal conditions, an exponential approximation34,42 still failed to adequately describe the earliest recovery points of Δ2–39 + KChIP2b.

Figure 4.

Effects of KChIP2b on macroscopic recovery kinetics (HP = −100 mV; protocol as per Fig. 3) of WT (solid black circles; n = 12) and Δ2–39 (hollow black circles; n = 13). Fits: WT + KChIP2b, single exponential with τ = 86 ms; Δ2–39 + KChIP2b: black sigmoidal curve, empirical “a1.6” fit with τ = 108 ms; blue curve, truncated single exponential beginning at Δt = 60 ms with τ = 126 ms. Gray symbols and fits correspond to WT (solid circles) and Δ2–39 (hollow circles) obtained in the absence of KChIP2b (previously illustrated in Fig. 4C). Dashed line, t50%. Extrapolated mean t50% values (determined as described in Fig. 3 caption) as follows: WT + KChIP2b, 74 ms; Δ2–39 + KChIP2b, 116 ms; WT, 145 ms; Δ2–39, 200 ms. Inset: Δ2–39 + KChIP2b, representative macroscopic recovery waveform at HP = −100 mV. For the oocyte illustrated, black curve is an empirical sigmoid “a2” fit with τ = 76 ms, while blue curve is a single exponential fit (begun at Δt = 40 ms) with τ = 90 ms. Calibration bar: 300 nA, 100 ms.

Mean t50% values for macroscopic recovery were determined and directly compared to those previously determined under basal conditions. Using t50% as a criterion, recovery (HP = −100 mV) of WT + KChIP2b was ∼1.57 times faster than Δ2–39 + KChIP2b. Nonetheless, KChIP2b produced similar relative acceleratory effects on t50% (WT, 1.97-fold acceleration; Δ2–39, 1.73-fold acceleration). Acceleration of KV4.3 macroscopic recovery by KChIP2b was therefore not dependent upon an intact N-terminus, although the rate of recovery was enhanced by its presence. These effects were not predicted from previous KV4.2 Δ2–40 + KChIP2.2 studies.42

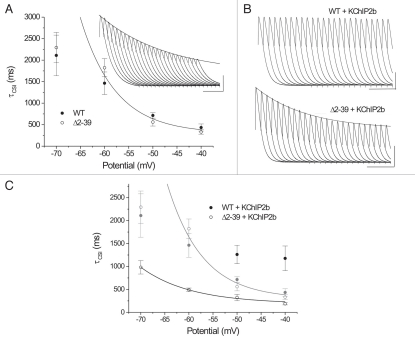

Kinetics of CSI.

Under basal conditions, the kinetics of development of CSI were measured over the potential range of −70 to −40 mV [i.e., at potentials with no to only minimal open state activation (Fig. 1B]. In contrast to macroscopic inactivation at +50 mV (Fig. 2), the mean kinetics of CSI (single exponential fits, Fig. 5A, inset) was similar between WT and Δ2–39 (Fig. 5A). N-terminal truncation therefore did not significantly alter the kinetics of development of CSI under basal conditions, effects consistent with previous KV4.2 Δ2–40 studies.34

Figure 5.

(A) Kinetics and potential dependence of development of CSI. (A) Basal conditions. Main panel: Mean time constants τcsi (derived from single exponential fits; see Inset) for development of CSI over the potential range of −70 to −40 mV. WT solid circles (n = 7–8), Δ2–39 hollow circles (n = 8–14). Combined aggregate mean data points from −60 to −40 mV fit with a single exponential function (solid black line; e-fold change in τcsi per 7.3 mV). Inset: Δ2–39, representative exponential fit (τ = 1,702 ms) to development of CSI at −60 mV. Calibration bar: 200 nA, 500 ms. (B) + KChIP2b. Representative current recordings obtained during application of CSI development protocol at −70 mV of WT + KChIP2b (no to minimal development of CSI; no fit; calibration bars: 750 nA, 500 ms) and Δ2–39 + KChIP2b (significant development of CSI fit with single exponential with τ = 944 ms; calibration bars: 1 µA, 500 ms). (C) Mean kinetics of CSI at HP = −70 to −40 mV for WT + KChIP2b (measured only at −50 and −40 mV; solid black circles; n = 3) and Δ2–39 + KChIP2b (n = 5–8; hollow black circles). Mean Δ2–39 + KChIP2b data points fit (black curve) with a single exponential function (e-fold change per 10.33 mV). The gray data points and curve are mean WT (solid circles) and Δ2–39 (open circles) data obtained under basal conditions (as illustrated in A).

While kinetics of CSI were not specifically analyzed in the previous KV4.2 + KChIP2.2 study,42 based upon its overall conclusions it was predicted that KChIP2b should not produce effects on KV4.3 Δ2–39 CSI kinetics. In contrast to this prediction,42 KChIP2b produced differential effects on CSI kinetics between WT and Δ2–39. Consistent with depolarization of the corresponding “i” curve (Fig. 1C), WT + KChIP2b displayed no to minimal CSI at HP = −70 and −60 mV (Fig. 5B, upper trace), with relatively rapid CSI developing only at the more depolarized potentials (Fig. 5C). Consistent with hyperpolarization of the corresponding “i” curve (Fig. 1C), Δ2–39 + KChIP2b displayed significantly accelerated kinetics of CSI at all potentials analyzed (Fig. 5B, lower trace, and C).

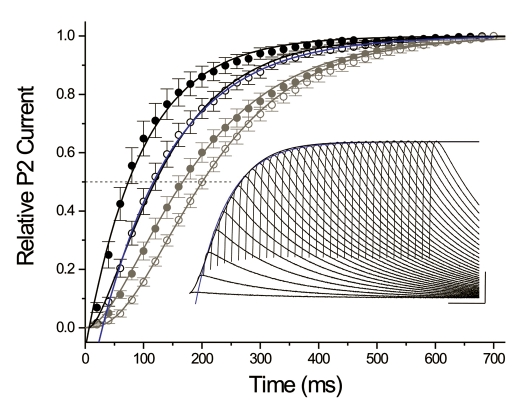

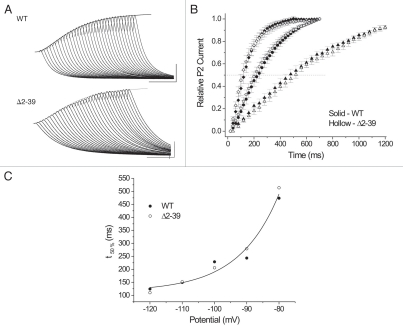

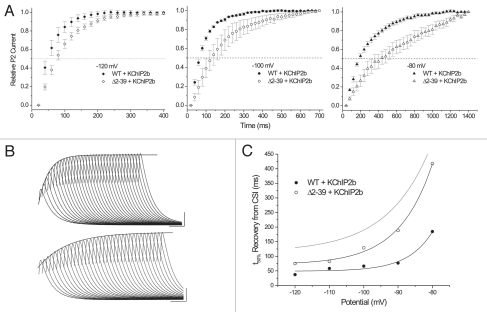

Recovery from CSI.

The kinetics of recovery from CSI (developed during a 2 s prepulse to −60 mV) were measured over the potential range of −80 to −120 mV. Under basal conditions, both WT and Δ2–39 displayed sigmoid CSI recovery kinetics (Fig. 6A) that were not significantly different (Fig. 6B). Mean t50% values for recovery from CSI were determined, and were also found to be very similar (Fig. 6C). In contrast, KChIP2b produced differential effects on CSI recovery between WT and Δ2–39 (Fig. 7). At all potentials analyzed, net rates of recovery from CSI were most rapid for WT + KChIP2b (Fig. 7A). Nonetheless, CSI recovery t50% values for Δ2–39 + KChIP2b were always more rapid than those obtained for both WT and Δ2–39 under basal conditions (Fig. 7C). KChIP2b-mediated acceleration of recovery from CSI was therefore not dependent upon an intact N-terminus, although acceleration was enhanced by its presence. While our results on basal effects of Δ2–39 on CSI recovery are generally consistent (see Discussion) with results obtained from prior KV4.2 Δ2–40 studies,34 effects of KChIP2b on CSI recovery kinetics were not predicted from subsequent KV4.2 Δ2–40 studies.42

Figure 6.

Recovery from CSI, basal conditions. (A) Representative recordings of recovery from CSI at HP = −100 mV for WT and Δ2–39. Empirical sigmoid “a2” fits: WT, τ = 195 ms; Δ2–39, τ = 203 ms. Calibration bars: WT 300 nA, 200 ms; Δ2–39 200 nA, 200 ms. (B) Mean CSI recovery waveforms for WT (solid symbols; n = 5–9) and Δ2–39 (hollow symbols; n = 5–9) at HP = −120 mV (diamonds), HP = −100 mV (circles), and HP = −80 mV (triangles). Similar mean CSI recovery curves were also measured for HP = −110 mV and HP = −90 mV [data not illustrated; these curves were used for extrapolation of t50% values at HP = −110 and HP = −90 mV illustrated in (C)]. Dashed line, 50% relative P2 current amplitude. (C) Extrapolated mean t50% values for recovery from CSI. Combined mean data points fit with a single exponential function (e-fold change per 12.4 mV).

Figure 7.

Effects of KChIP2b on recovery from CSI. (A) Mean recovery waveforms from CSI at HP = −120, −100, and −80 mV (WT + KChIP2b, solid symbols, n = 4–7; Δ2–39 + KChIP2b, hollow symbols, n = 4–9). Relative peak current amplitudes normalized. Additional mean CSI recovery waveforms were measured at HP = −110 and −90 mV [mean data not illustrated; but see (B)]. Dashed line, 50% relative P2 current amplitude. (B) Δ2–39 + KChIP2b, representative CSI recovery waveforms measured at HP = −110 mV (upper panel: fit to waveform approximated with a single exponential with τ = 67 ms; calibration bars: 500 nA, 100 ms) and HP = −90 mV (lower panel: fit to waveform approximated with a single exponential with τ = 195 ms; calibration bars: 500 nA, 100 ms). Single exponential fits, while well describing the majority of peak currents measured at later times, nonetheless failed to adequately describe the earliest peak currents. (C) Mean extrapolated t50% values for recovery from CSI. Mean data points fit with single exponential functions (WT + KChIP2b, e-fold change per 7.15 mV; Δ2–39 + KChIP2b, e-fold change per 9.78 mV). The gray curve is fit to WT and Δ2–39 t50% values (as illustrated in Fig. 6C).

Discussion

The KV4.3 proximal N-terminal truncation mutant Δ2–39 produced two general effects: (i) An increase in macroscopic current peak amplitude; and (ii) Alteration of specific gating transitions. Both the increase in current amplitude and some of the gating effects produced by Δ2–39 (recorded under “reduced amplitude” conditions) are in agreement with previous KV4.2 Δ2–40 studies.34,42 However, KV4.3 Δ2–39 specifically altered macroscopic versus closed gating transitions, measured under basal conditions and in the presence of KChIP2b, in ways not predicted from previous KV4.2 studies. Among these latter results, possibly the most surprising were the following: (i) Δ2–39 slowed both deactivation and recovery from macroscopic inactivation; (ii) KChIP2b accelerated Δ2–39 deactivation and macroscopic recovery; and (iii) KChIP2b altered Δ2–39 CSI characteristics. These findings suggest that mechanisms proposed to underlie KV4 inactivation and recovery2,3,5,7,34–37,40–42 may need reevaluation and/or revision.

Our coexpression measurements focused exclusively on KChIP2b. In addition to KChIPs, several additional β subunits may also be physiologically relevant modulators of KV4 channels.3,8 Such additional β subunits include dipeptidylaminopeptidase-like proteins (DPPX isoforms),50–55 Min-K related peptides (MiRPs),56–60 and KVβ isoforms.57,61,62 All of these additional β subunits have been demonstrated to either colocalize with KV4 channels and/or alter various KV4 gating characteristics.3 However, while such results are suggestive, it has not been established for any of these additional β subunits that they are intrinsic components of the native KV4 channel complex expressed in specific cardiac myocytes or neurons. To date, only KChIP2 has been directly demonstrated to be an intrinsic component of native cardiac Ito, fast.3,39 Furthermore, in the absence of well-defined mechanisms, analyzing effects of coexpression of multiple β subunits may significantly complicate or obscure analysis. For example, when MiRP3 and KChIP2 are coexpressed separately with KV4.2, each β subunit produces distinct effects on gating characteristics.60 However, when MiRP3 + KChIP2 are simultaneously coexpressed net effects on KV4.2 gating closely resemble those of KChIP2 expressed alone. While these results60 have implications for mechanisms underlying different Ito, fast phenotypes expressed in distinct anatomical regions of the ventricle of the heart,1–3 they also demonstrate some of the complexities that can arise from multiple coexpression studies. Therefore, while we acknowledge that our present analysis of KChIP2b coexpression is likely not fully representative of intact physiological conditions, such a simplified approach eliminates interpretive complications potentially introduced by coexpression of multiple β subunits. Once effects of KChIP2b are clearly understood, subsequent analysis of additional β subunits, expressed alone and in the presence of KChIP2b, should result in more insightful mechanistic interpretations. So as to put our KChIP2b findings into an appropriate context, in the following relevant sections these considerations need to be kept in mind.

Δ2–39 increases KV4.3 peak current amplitude.

A large increase in peak current amplitude produced by N-terminal truncation was originally noted in studies of KV4.2 Δ2–40 (∼55-fold greater compared to WT).42 In the present study, because very large Δ2–39 currents displayed signs of voltage clamp failure, no further efforts to quantify the increase in current amplitude were made. Rather, the focus of this study was to characterize effects of Δ2–39 on KV4.3 gating characteristics. In this regard, under “reduced amplitude” conditions no significant differences in steady-state “a4” activation or isochronal 1 s inactivation “i” relationships between WT KV4.3 and Δ2–39 currents were noted. These results suggest that alterations in these two gating characteristics do not contribute to increased current amplitudes produced by Δ2–39. It has been proposed that the KV4 N-terminus functions as an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal and binding of KChIPs would mask this site, resulting in increased expression of channel protein.5,42,67,68 However, a functional ER retention signal has yet to be identified in the KV4 N-terminus.3,69 Thus, while the increase in current amplitude produced by Δ2–39 is consistent with prior KV4.2 studies,42 the mechanism(s) underlying these effects are unresolved.

Effects of Δ2–39 on KV4.3 gating characteristics.

Basal conditions. Many of the effects of Δ2–39 on KV4.3 gating characteristics that we measured are in good agreement with previous KV4.2 Δ2–40 studies. Specifically, both KV4.2 Δ2–4034 and KV4.3 Δ2–39 mutants (i) did not significantly alter activation “a4” or inactivation “i” relationships (the latter monitoring isochronal characteristics of CSI), (ii) slowed deactivation kinetics, (iii) moderately slowed (∼2- to 3-fold) macroscopic inactivation and (iv) did not significantly alter either development of or recovery from CSI. There is thus consensus on effects of N-terminal truncation on these specific KV4 channel-gating characteristics. Overall, these combined results indicate that deletion of the proximal N-terminus does not alter KV4 channel activation or CSI characteristics, but rather stabilizes the channel open state(s) once it has been reached.

In contrast to the above discussed similarities, the kinetics of recovery from macroscopic inactivation in KV4.3 Δ2–39 were found to be more complicated than those predicted from prior KV4.2 studies. Bahring et al.34 reported that Δ2–40 did not significantly alter KV4.2 macroscopic recovery kinetics, effects which were quantified using “conventional” exponential functions. In contrast, we consistently observed some degree of sigmoidicity in KV4.3 recovery. While this was relatively minimal for WT, it was always present in Δ2–39. Thus, at all fixed potentials net recovery from macroscopic inactivation of Δ2–39 was always slower than that of WT (as quantified using either t50% values or truncated exponential approximations). Underlying reasons for the discrepancy between our results and those reported by Bahring et al.34 are unclear, but may reside in differences in both fitting procedures (exponential versus sigmoidal/t50% values; details in Figs. 3 and 4) and expression systems. In our original study of KChIP2 isoforms,48 using immunoblot analysis (pan KChIP2 antibody) we found no evidence for expression of endogenous KChIP2 isoforms in Xenopus oocytes, but we did obtain evidence for their existence in HEK, CHO and COS cells. We have thus conducted all of our subsequent KV4.3 studies using Xenopus oocytes. In their KV4.2 Δ2–40 study Barhing et al.34 employed HEK cells. Their measurements thus may have been inadvertently biased (at least to some degree) by endogenous KChIP2 isoforms, a possibility consistent with our present results.

How can macroscopic and CSI sigmoid recovery kinetics arise, and what does such sigmoidicity imply? While underlying mechanisms are unresolved, evidence has accumulated for a probable role of the voltage-sensing domain (VSD; transmembrane segments S1–S4) in regulating not only KV4 activation and deactivation but also inactivation and recovery.63–66,70,71 Our laboratory has previously demonstrated that S4 and S3 individual charge deletion or addition mutants produce corresponding changes in deactivation and recovery: charge mutants that slow deactivation also slow recovery, while charge mutants that accelerate deactivation also accelerate recovery.63–66 These results suggest that KV4.3 recovery is coupled to deactivation, i.e., “reverse” movement of the VSD. Sigmoid recovery could thus arise from two or more VSDs undergoing deactivating transitions (independently or cooperatively), multiple inactivated states or a combination of these two mechanisms. Hence, any process that alters KV4 deactivation would be predicted to alter recovery. We thus wish to emphasize that Δ2–39 slowed both KV4.3 deactivation and macroscopic recovery, a novel finding providing additional support for our prior proposal of recovery being coupled to deactivation.63–66 Barghaan et al.37 have proposed the term “deactivation-inactivation coupling” as a descriptor for N-terminal effects in regulating KV4.2 gating transitions. We suggest a more accurate term may be “deactivation-recovery coupling”.

If our proposal of KV4.3 deactivation-recovery coupling is correct, the next challenge will be to determine the location(s) of the α subunit domain(s) that the proximal N-terminal interacts with. Our present results indicate that under basal conditions this site(s) becomes accessible only in the open-state state conformation. While this characteristic is consistent with an N-type-like mechanism,35,36 our results do not allow us to conclude that the N-terminal interaction site(s) is located in the conduction pore. Other possibilities may include state-dependent regions that become accessible in the VSD (S2–S3 linker, putative intracellular cavity72), the S4–S5 linker,72,73 and/or the C-terminus.45,46

KChIP2b coexpression. It has been reported that KV4.2 Δ2–40 channels are unable to functionally interact with KChIP2 isoforms.37,42 However, we observed that KChIP2b could alter several Δ2–39 gating characteristics. Such KChIP2b-mediated effects were thus not obligatorily dependent upon an intact N-terminus. These effects included hyperpolarization of “a4” and “i” relationships and acceleration of the kinetics of deactivation, CSI and recovery from both macroscopic and CSI. While reasons for the discrepancy between our results and prior KV4.2 Δ2–4042 studies are unclear, as previously discussed differences in both analytical procedures and expression systems may be contributing factors.

Our results were obtained from analysis of net functional effects of KChIP2b on specific Δ2–39 gating transitions. We thus cannot make any conclusions on the location(s) of the KChIP2b interaction site(s) underlying these effects. For example, we cannot rule out that KChIP2b coexpression may have altered (through presently unrecognized pathways) an intracellular signaling cascade and/or a metabolic process, the net effects of which could underlie some of our results. Other potential scenarios can also be envisioned. Having acknowledged such possibilities, in the present absence of data supporting additional KChIP2-mediated pathways we propose that the most straightforward explanation for our results would be the existence of KChIP2b interaction sites located in α subunit domains outside of the proximal N-terminal. Our results argue that such putative KChIP2b interaction sites would be functionally relevant and interaction(s) of KChIP2b with them would not be obligatorily dependent upon an intact N-terminal proximal domain. However, our results also suggest that the efficiency of KChIP2b interaction(s) with these putative sites may be increased by an intact N-terminal.

Assuming that additional KChIP2b interaction sites exist outside of the KV4.3 proximal N-terminal, based upon prior studies we can reasonably speculate on their possible location(s). One obvious candidate would be “site 2” in the T1 domain identified in crystallographic studies.40,41 In addition, evidence for KChIP interaction sites existing in KV4.2 C-terminal domains has also been reported. Callsen et al.45 noted that various KV4.2 C-terminal deletion mutants displayed significantly altered KChIP2 binding ability. These investigators45 concluded that KChIP2 interaction sites likely exist in C-terminal domains, although interactions with these domains were proposed to be “more loose” than those mediated by the proximal N-terminal. A subsequent study by Han et al.46 reported that progressive C-terminal truncation mutants both lowered KV4.2 surface expression and altered interactions with KChIP2, results again consistent with KChIP2/C-terminal interactions. The reported “looseness” of KV4.2 C-terminal/KChIP2 interactions45 does appear to be generally consistent with our proposal that the presence of an intact KV4.3 N-terminal may increase the efficiency of KChIP2b interaction(s) with putative additional regulatory sites.

Mechanisms underlying these C-terminal related effects45,46 are unresolved. However, it is known that KV4 channels possess C-terminals, which are considerably longer than their N-terminals.2–4 Such elongated C-terminals are hypothesized to form the prominent “peripheral columns” that have been observed in low-resolution electron microscopic studies of KV4 channels.74 It is unclear if these peripheral columns are relatively “static” or can undergo voltage-dependent conformational changes. Nonetheless, these EM results74 provide further evidence that KChIPs may interact with KV4 C-terminal domains.

Implications.

While the physiological implications of our results are presently unclear, our proposal of functionally relevant KChIP2 binding sites existing in regions outside of the KV4.3 proximal N-terminal may provide a basis, at least in part, for some of the previously reported effects of novel KChIP2 isoforms on KV4 channels.2,3,47–49,75 Specific mutations in either or both the N-terminal domain and additional KChIP2 interaction sites could potentially alter such regulatory effects. Our results also raise the possibility of developing future therapeutic agents that not only specifically target KV4 channels, but may also exert effects specifically on one or only a few select gating processes. Finally, KChIP2 has recently been demonstrated to alter both transcriptional and electrophysiological properties of the cardiac L-type calcium channel CaV1.2.76,77 While these CaV1.2 effects are clearly beyond the scope of our present study, they do provide independent evidence that KChIP2 interaction sites can exist in protein domains outside of the KV4 N-terminus.

Summary and conclusions.

Our results indicate that under basal conditions the KV4.3 proximal N-terminus is not significantly involved in regulating closed state gating transitions, but rather regulates transitions occurring after entrance into the open state(s). Deactivation and recovery from macroscopic and CSI (which is a sigmoidal process for both pathways) are slowed by N-terminal truncation, consistent with our prior proposal of recovery being coupled to deactivation. Our results further indicate that KChIP2b-mediated effects on KV4.3 are not obligatorily dependent upon an intact N-terminal proximal domain. To account for these effects we propose that additional KChIP interaction sites exist in α subunit domains outside of the proximal N-terminus. Taken together, our results suggest that in addition to regulating macroscopic inactivation the KV4.3 N-terminal may also act as a regulator of deactivation-recovery coupling. Interactions of KChIP2 isoforms with both the KV4 N-terminal and hypothesized sites located in additional domains may provide mechanisms for further “fine tuning” of KChIP2-mediated effects.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis, in vitro transcription and oocyte preparation.

KV4.3 (long form, GenBank AF454388) and KChIP2b (GenBank AF454387.1) were originally cloned from ferret heart as described previously,47,48 and maintained in pBluescript KS(+) vector. The KV4.3 N-terminal truncation mutant Δ2–39, which deletes amino acids 2–39, was constructed by designing the reverse primer (sequence: GAG CTA ATC GTC CTC AAC GTG) immediately upstream of codon 2 and the forward primer (sequence: CAT GGT GAC TCC AGC TCT TGG) immediately downstream of codon 39. PCR reaction conditions were as described previously63 using the PfuUltra DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Mutant specificity was confirmed by sequencing (DNA Sequencing Core Facility, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY). KV4.3 wild-type (WT) and mutant clone plasmids were linearized with the restriction endonuclease XhoI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). cRNA was synthesized by the mMessage mMachine T7 Ultra Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). cRNA quantity and quality was evaluated by spectroscopy and agarose gel electrophoresis.

All animal protocols were conducted in accordance with NIH-approved guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University at Buffalo, SUNY. Oocytes were obtained from Xenopus laevis euthanized by soaking in a lethal concentration of 6.0 g/L ethyl-3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate salt. Oocytes were enzymatically (collagenase) defolliculated,47–49,63–66 injected (12–24 hours after isolation) with cRNA (Nanoject II; Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA), and incubated (17°C) for ∼12–72 hours (see Results for further details). For coexpression studies (WT KV4.3 + KChIP2b, Δ2–39 + KChIP2b) respective cRNA concentrations were injected in 1:1 ratios.

Electrophysiology, voltage clamp protocols and analysis.

Two-microelectrode voltage clamp recordings (GeneClamp 500B, Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) were conducted (22°C) in ND96 solution (in mM: 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgSO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 HEPES, pH = 7.40). All current recordings were conducted at maximal gain of the amplifier (10,000×), clamp rise time stability settings of ∼60–150 µs, and filtered at 1 kHz [digitized at 5 kHz; Digidata 1320A 16-bit acquisition system run under pClamp 9 software control (Axon Instruments)]. Subsequent analysis was conducted using either pClamp 9 or Origin (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA).

Voltage clamp protocols and analyses were similar to our recent KV4.3 studies.63–66 Steady-state activation “a4” curves were constructed from saturating P2 tail currents (500 ms P2 pulses to −40 mV) elicited following a series of 15 ms depolarizing P1 pulses (applied from HP = −100 mV) to progressively depolarized potentials. Assuming independent gating, peak tail current amplitudes were normalized and mean data points best fit to a single Boltzmann relationship raised to the fourth power:

where k is slope factor (mV), V membrane potential (mV) and V1/2 potential of half maximal activation (mV). Isochronal inactivation “i” relationships were measured by applying a series of 1 second P1 pulses (applied from HP = −100 mV) to progressively depolarized potentials, followed by a 1 second P2 pulse to +50 mV. P2 current amplitudes were normalized, plotted as a function of P1 potential and mean data points best fit to a single Boltzmann relationship:

where k is slope factor (mV), V membrane potential (mV) and V1/2 potential of half maximal inactivation (mV).

Macroscopic inactivation kinetics produced during a total 2 second depolarization to +50 mV (generated by identical P1 and P2 pulses to +50 obtained during measurements of isochronal [1 second] “i” relationships) were fit using pClamp. Single, double and/or triple exponential kinetics were all attempted, and the minimal number of exponential components that the majority of measurements acceptably supported are reported in Table 2. Fits were considered unacceptable if the slowest component had an exceedingly small relative amplitude (<0.01), a negative time constant was generated, the slowest time constant was >1.4 s (i.e., durations well over half of the total depolarizing pulse duration), or a combination of such effects. Time constants of deactivation τdeact were directly measured by applying a 15 ms P1 pulse to +50 mV immediately followed by a P2 pulse (500 ms) to various hyperpolarized potentials. To avoid contamination by capacitive current transients, single exponential fits were begun ∼2–3 ms after stepping to a given P2 potential.

Recovery from macroscopic inactivation was measured using a conventional P1–P2 double pulse protocol. From HP = −100 mV, a 1 second P1 pulse to +50 mV was applied. Following return to HP = −100 to −70 mV for variable periods of time (Δt), an identical P2 pulse was applied. Peak P2 current amplitude was normalized, plotted as a function of Δt and subsequently fit (see Results for further details). Kinetics of development of closed state inactivation (CSI) were analyzed using a P1 prepulse applied from −70 to −40 mV of progressively increasing duration, followed by a 1 second P2 pulse to +50 mV. Decline of P2 current as a function of P1 duration (single exponential fits) allowed determination of the time constant τCSI of development of CSI. Kinetics of recovery from CSI (developed during a 2 second P1 prepulse to −60 mV and analyzed over the holding potential range of HP = −120 to −80 mV) were determined by plotting the amplitude of peak P2 current at +50 mV (1 second pulse) as a function of P1 duration at each HP.

Statistical significance (p < 0.01) was determined by ANOVA (Origin). All data points in figures are mean ± SEM. With exception of comparative overlays of normalized peak transient currents, all illustrated current recordings are not “leakage corrected”.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health (MH08678901) (Donald L. Campbell) and the American Heart Association, Northeast Affiliate (0715759T) (Matthew R. Skerritt).

Abbreviations

- CSI

closed state inactivation

- KChIP2b

potassium channel interacting protein 2b

- HP

holding potential

- VSD

voltage sensing domain

References

- 1.Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Oudit GY, Gidrewicz D, Triveri MG, Zoble C, Backx PH. Regulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling by action potential repolarization: role of the transient potassium current (Ito) J Physiol. 2003;546:5–18. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel SP, Campbell DL. Transient outward potassium current, “Ito”, phenotypes in the mammalian left ventricle: underlying molecular, cellular and biophysical mechanisms. J Physiol. 2005;569:7–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niwa N, Nerbonne JM. Molecular determinants of cardiac transient outward potassium current (Ito) expression and regulation. J Molec Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaum SG, Varga AW, Yuan LL, Anderson AE, Sweatt JD, Schrader LA. Structure and function of KV4-family transient potassium channels. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:803–833. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jerng HH, Pfaffinger PJ, Covarrubias M. Molecular physiology and modulation of somatodendritic A-type potassium channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:343–369. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson SM. IA in play. Neuron. 2007;54:850–852. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Covarrubias M, Bhattacharji A, De Santiago-Castillo JA, Dougherty K, Kaulin YA, Na-Phuket TR, Wang G. The neuronal KV4 channel complex. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:1558–1567. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9650-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vacher H, Mohapatra, Trimmer JS. Localization and targeting of voltage-dependent ion channels in mammalian central neurons. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1407–1447. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Wei DS, Hoffman DA. KV4 potassium channel subunits control action potential repolarization and frequency-dependent broadening in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2005;569:41–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J, Jung SC, Clemens AM, Petralia RS, Hoffman DA. Regulation of dendritic excitability of activity-dependent trafficking of the A-type K+ channel subunit KV4.2 in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2007;54:933–947. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu HJ, Carrasquillo, Karim F, Jung WE, Nerbonne JM, Schwarz TL, Gereau RW. The KV4.2 potassium channel subunit is required for pain plasticity. Neuron. 2006;50:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comer MB, Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Lamson DR, Morales MJ, Zhang Y, Strauss HC. Cloning and characterization of an Ito-like potassium channel from ferret ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:1383–1389. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.4.H1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoshi T, Zagotta WN, Aldrich RW. Biophysical and molecular mechanisms of Shaker potassium channel inactivation. Science. 1990;250:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.2122519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zagotta WN, Hoshi T, Aldrich RW. Restoration of inactivation in mutants of Shaker potassium channels by a peptide derived from ShB. Science. 1990;250:568–571. doi: 10.1126/science.2122520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoshi T, Zagotta WN, Aldrich RW. Two types of inactivation in Shaker K+ channels: effects of alterations in the carboxy-terminal region. Neuron. 1991;7:547–556. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi KI, Aldrich RW, Yellen G. Tetraethylammonium blockade distinguishes two inactivation mechanisms in voltage-activated K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5092–5095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Barneo J, Hoshi T, Heinemann SH, Aldrich RW. Effects of external cations and mutations in the pore region on C-type inactivation of Shaker potassium channels. Receptors and Channels. 1993;1:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demo SD, Yellen G. The inactivation gate of the Shaker K+ channel behaves like an open-channel blocker. Neuron. 1991;7:743–753. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baukrowitz T, Yellen G. Modulation of K+ current by frequency and external [K+]: a tale of two inactivation mechanisms. Neuron. 1995;15:951–960. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmusson RL, Morales MJ, Castellino RC, Zhang Y, Campbell DL, Strauss HC. C-type inactivation controls recovery in a fast inactivating cardiac K+ channel (KV1.4) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1995;489:709–721. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yellen G. The moving parts of voltage-gated ion channels. Quart Rev Biophys. 1998;31:239–295. doi: 10.1017/s0033583598003448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmusson RL, Morales MJ, Wang S, Liu S, Campbell DL, Strauss HC. Inactivation of voltage-gated cardiac K+ channels. Circ Res. 1998;20:739–750. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bezanilla F. The voltage sensor in voltage-dependent ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:555–592. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aldrich RW. Fifty years of inactivation. Nature. 2001;411:643–644. doi: 10.1038/35079705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou M, Morals-Cabral JH, Mann S, MacKinnon R. Potassium channel receptor site for the inactivation gate and quaternary amine inhibitors. Nature. 2001;411:657–661. doi: 10.1038/35079500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3rd Edition. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Inc; 2001. Gating. Voltage sensing and inactivation; 603 pp.634 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korn SJ, Trapani JG. Potassium channels. IEEE Trans Nanobioscience. 2005;4:21–33. doi: 10.1109/tnb.2004.842466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bezanilla F. Voltage-gated ion channels. IEEE Trans Nanobioscience. 2005;4:34–48. doi: 10.1109/tnb.2004.842463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bett GCL, Rasmusson RL. Modification of K+ channel-drug interactions by ancillary subunits. J Physiol. 2008;586:929–950. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahidullah M, Covarrubias M. The link between ion permeation and inactivation gating of KV4 potassium channels. Biophys J. 2003;84:928–941. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74910-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amadi CC, Brust RD, Skerritt MR, Campbell DL. Regulation of KV4.3 closed state inactivation and recovery by extracellular potassium and intracellular KChIP2b. Channels. 2007;1:305–314. doi: 10.4161/chan.5017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrader LA, Anderson AE, Mayne A, Pfaffinger PJ, Sweatt JD. PKA modulation of KV4.2-encoded A-type potassium channels requires formation of a supramolecular complex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10123–10133. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10123.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jerng HH, Corvarrubias M. K+ channel inactivation mediated by the concerted action of the cytoplasmic N- and C-terminal domains. Biophys J. 1997;72:163–174. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78655-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahring R, Boland LM, Vargese A, Gebauer M, Pongs O. Kinetic analysis of open- and closed-state inactivation transitions in human KV4.2 A-type potassium channels. J Physiol. 2001;535:65–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pourrier M, Herrera D, Caballero R, Schram G, Wang Z, Nattel S. The KV4.3 N-terminal restores fast inactivation and confers KChIP2 modulatory effects on N-terminal-deleted KV1.4 channels. Pflugers Arch. 2004;449:235–247. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gebauer MD, Isbrandt K, Sauter B, Callsen A, Nolting O, Pongs O, Bahring R. N-type inactivation features of KV4.2 channel gating. Biophys J. 2004;86:210–223. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barghaan J, Tozakidou M, Ehmke H, Bahring R. Role of N-terminal domain and accessory subunits in controlling deactivation-inactivation coupling of KV4.2 channels. Biophys J. 2008;94:1276–1294. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.An WF, Bowlby MR, Betty M, Cao J, Ling HP, Mendoza G, et al. Modulation on A-type potassium channels by a family of calcium sensors. Nature. 2000;403:553–556. doi: 10.1038/35000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuo HC, Chen CF, Clark RB, Lin J, Gu Y, Ikeda Y, et al. A defect in the KV channel-interacting protein 2 (KChIP2) gene leads to a complete loss of Ito and confers susceptibility to ventricular tachycardia. Cell. 2001;107:801–813. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pioletti M, Findeisen F, Hura GL, Minor DL. Threedimensional structure of the KChiP1-KV4.3 T1 complex reveals a cross-shaped octamer. Nature Struc Mol Biol. 2006;13:987–995. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang HY, Yan Q, Liu Y, Huang Y, Shen L, Chen Y, et al. Structural basis for modulation of KV4 K1 channels by auxiliary KChIP subunits. Nature Neurosci. 2007;10:32–39. doi: 10.1038/nn1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bahring R, Dannenberg J, Peters HC, Leicher T, Pongs O, Isbrandt D. Conserved KV4 N-terminal domain critical for effects of KV channel—interacting protein 2.2 on channel expression and gating. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23888–23894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minor DL, Lin YF, Mobley BC, Avelar A, Jan YN, Jan LY, Berger JM. The polar T12 interface is linked to conformational changes that open the voltage-gated potassium channel. Cell. 2000;102:657–670. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang G, Covarrubias M. Voltage-dependent gating rearrangements in the intracellular T1–T1 interface of a K+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:391–400. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Callsen B, Isbrandt D, Sauter K, Hartmann LS, Pongs O, Bahring R. Contribution of N- and C-terminal KV4.2 channel domains to KChIP interaction. J Physiol. 2005;568:397–412. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han W, Nattel S, Noguchi T, Shrier A. C-terminal domain of KV4.2 and associated KChIP2 interactions regulate functional expression and gating of KV4.2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27134–27144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604843200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel SP, Campbell DL, Strauss HC. Elucidating KChIP effects on KV4.3 inactivation and recovery kinetics with a minimal KChIP2 isoform. J Physiol. 2002;545:5–11. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel SP, Campbell DL, Morales MJ, Strauss HC. Heterogeneous expression of KChIP2 isoforms in the ferret heart. J Physiol. 2002;539:649–656. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.015156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel SP, Parai R, Parai R, Campbell DL. Regulation of KV4.3 voltage-dependent gating kinetics by KChIP2 isoforms. J Physiol. 2004;557:19–41. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nadal MS, Ozata A, Amarillo Y, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Ma Y, Mo W, et al. The CD26-related dipeptidylaminopeptidase-like protein DPPX is a critical component of neuronal A-type K+ channels. Neuron. 2003;37:449–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jerng HJ, Qian Y, Pfaffinger PJ. Modulation of KV4.2 channel expression and gating by dipeptidyl peptidase 10 (DPP10) Biophys J. 2004;87:2380–2396. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.042358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radicke S, Cotella D, Graf EM, Ravens U, Wettwer E. Expression of function of depeptidyl-aminopeptidase-like protein 6 as a putative β-subunit of human cardiac transient outward current encoded by KV4.3. J Physiol. 2005;565:751–756. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Radicke S, Cotella D, Bortoluzzi, Ravens U, Wettwer W, Sblattero D. DPP10-A new putative regulatory β-subunit of Ito in failing and non-failing human heart. Circulation. 2007;116:187. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amarillo Y, De Santiago-Castillo JA, Dougherty K, Maffie J, Kwon E, Covarubbias M, Rudy B. Ternary KV4.2 channels recapitulate voltage-dependent inactivation kinetics of A-type K+ channels in cerebellar granule cells. J Physiol. 2008;586:2093–2106. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim J, Nadal MS, Clemens AM, Baron M, Jung SC, Misumi Y, et al. KV4 accessory protein DPPX (DPP6) is a critical regulator of membrane excitability in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1835–1847. doi: 10.1152/jn.90261.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang M, Jiang M, Tseng GN. MinK-related peptide 1 associates with KV4.2 and modulates its gating function:Potential role as β-subunit of cardiac transient outward channel? Cir Res. 2001;88:1012–1019. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deschenes I, Tomaselli GF. Modulation of KV4.3 current by accessory subunits. FEBS Lett. 2002;528:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCossan ZA, Abbott GW. The Min-K related peptides. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:787–821. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lundy A, Olesen SP. KCNE3 is an inhibitory subunit of the KV4.3 potassium channel. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2006;346:958–967. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levy DI, Cepaitis E, Wandelring S, Toth PT, Archer SL, Goldstein SAN. The membrane protein MiRP3 regulates KV4.2 channels in a KChIP-dependent manner. J Physiol. 2010;55:2657–2668. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perez-Garcia MT, Lopez-Lopez JR, Gonzalez C. KVβ1.2 subunit coexpression in HEK 293 cells confers O2 sensitivity to KV4.2 but not to Shaker channels. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:897–907. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.6.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang EK, Alvira MR, Levitan ES, Takimoto K. KVβ subunits increase expression of KV4.3 channels by interacting with their C-terminus. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4839–4844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skerritt MR, Campbell DL. Role of S4 positively charged residues in the regulation of KV4.3 inactivation and recovery. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:96–914. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00167.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Skerritt MR, Campbell DL. Non-native R1 substitution in the S4 domain uniquely alters KV4.3 channel gating. PloS One. 2008;3:3773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skerritt MR, Campbell DL. Contribution of electrostatic and structural properties of KV4.3 S4 arginine residues to the regulation of channel gating. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Biomembranes. 2009;1788:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skerritt MR, Campbell DL. KV4.3 gating and expression: S2 and S3 acidic and S4 innermost basic residues. Channels. 2009;3:1–14. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.6.9867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shibata R, Misinou H, Campomanesi CR, Anderson AE, Schrader LA, Doliveria LC, et al. A fundamental role for KChIPs in determining the molecular properties and trafficking of KV4.3 potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36445–36454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306142200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ma D, Jan LY. ER transport signals and the trafficking of potassium channels and receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:287–292. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hasdemir B, Fitzgerald DJ, Prior IA, Tepikine AV, Burgoyne RD. Trafficking of KV4 K+ channels mediated by KChIP1 is via a novel post-ER vesicular pathway. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:459–469. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dougherty K, Covarrubias M. A dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like protein remodels gating charge dynamics in KV4.2 channels. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:745–753. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dougherty K, De Santiago-Castillo JA, Covarrubias M. Gating charge immobilization in KV4.2 channels: The basis of closed-state inactivation. J Gen Physiol. 2008;131:257–273. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tombola F, Pathak MM, Isacoff EY. How does voltage open an ion channel? Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:23–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020404.145837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barghaan J, Bahring R. Dynamic coupling of voltage sensor and gate involved in closed-state inactivation of KV4.2 channels. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:205–224. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim LA, Furst J, Gutierrerz D, Butler MH, Xu S, Goldstein SAN, Grigorieff N. Three dimensional dimensional structure of Ito: KV4.2-KChIP2 ion channels by electronmicroscopy at 21 Å resolution. Neuron. 2004;41:513–519. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Decher N, Barth AS, Gonzalez T, Steinmeyer K, Sanguinetti MC. Novel KChIP2 isoforms increase functional diversity of transient outward potassium currents. J Physiol. 2004;557:761–773. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomsen MB, Wang C, Ozgen N, Wang HG, Rosen MR, Pier GS. Accessory subunit KChIP2 modulates the cardiac L-type calcium current. Circ Res. 2009;104:1382–1389. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.196972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thomsen MB, Foster E, Nguyen KH, Sosunov EA. Transcriptional and electrophysiological consequences of KChIP2-mediated regulation of CaV1.2. Channels. 2009;3:1–3. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.5.9560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]