Summary

Background and objectives

Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) has emerged as a new factor in mineral metabolism in chronic kidney disease (CKD). An important regulator of phosphorus homeostasis, FGF-23 has been shown to independently predict CKD progression in nondiabetic renal disease. We analyzed the relation between FGF-23 and renal outcome in diabetic nephropathy (DN).

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

DN patients participating in a clinical trial (enalapril+placebo versus enalapril+losartan) had baseline data collected and were followed until June 2009 or until the primary outcome was reached. Four patients were lost to follow-up. The composite primary outcome was defined as death, doubling of serum creatinine, and/or dialysis need.

Results

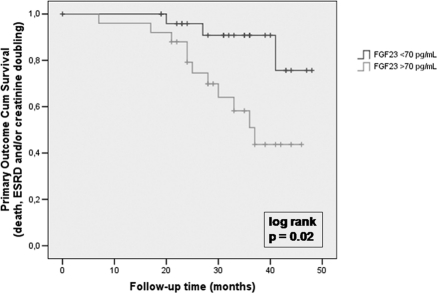

At baseline, serum FGF-23 showed a significant association with serum creatinine, intact parathyroid hormone, proteinuria, urinary fractional excretion of phosphate, male sex, and race. Interestingly, FGF-23 was not related to calcium, phosphorus, 25OH-vitamin D, or 24-hour urinary phosphorus. Mean follow-up time was 30.7 ± 10 months. Cox regression showed that FGF-23 was an independent predictor of the primary outcome, even after adjustment for creatinine clearance and intact parathyroid hormone (10 pg/ml FGF-23 increase = hazard ratio, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.16, P = 0.02). Finally, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a significantly higher risk of the primary outcome in patients with FGF-23 values of >70 pg/ml.

Conclusions

FGF-23 is a significant independent predictor of renal outcome in patients with macroalbuminuric DN. Further studies should clarify whether this relation is causal and whether FGF-23 should be a new therapeutic target for CKD prevention.

Introduction

In the past years, mineral metabolism abnormalities have been implicated in the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients (1–5). Interestingly, the role of mineral metabolism on CVD might go beyond CKD because recent evidence suggests that phosphorus excess is also related to CVD in the non-CKD populations (6–8). Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) has emerged as a new component on phosphorus homeostasis. In phosphorus excess conditions, bone FGF-23 production is increased, causing phosphaturia and reduced 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D levels. In addition, it has been shown that knockout animal models for FGF-23-klotho axis are related to a premature-aging syndrome, suggesting a possible role of phosphorus excess in the aging process.

In epidemiologic studies, increased levels of FGF-23 have been positively related with mortality in dialysis patients (9,10). FGF-23 has also been related to cardiovascular events (11), left ventricular hypertrophy (12), endothelial dysfunction (13), and total body atherosclerosis in the general population (14).

All of these findings raise the possibility that FGF-23 might also contribute to CKD progression. A recent report by Fliser et al. (15) suggests that FGF-23 is related to CKD in a nondiabetic CKD population. However, it is not clear whether the same relationship is observed in the setting of diabetic nephropathy (DN) (16). In this paper, we wished to explore the relationship between serum FGF-23 and the risk of CKD progression in patients with macroalbuminuric DN.

Materials and Methods

This is an ancillary study of a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial (NCT 419835) designed to compare the effect of association therapy of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor plus angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) versus monotherapy with ACE inhibitor on proteinuria progression (17).

Briefly, we enrolled patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and macroalbuminuric DN seen at the Nephrology Outpatient Service in the Hospital das Clínicas (São Paulo, Brazil). Recruitment took place between May 2005 and September 2007, and the study was finished by May 2008. Inclusion criteria were defined as: (1) diabetes mellitus for more than 5 years and (2) proteinuria above 500 mg/d. All of the incident and prevalent patients from outpatient services meeting these inclusion criteria were invited to participate. Exclusion criteria were: (1) serum creatinine above 2.5 mg/dl; (2) serum potassium above 5.5 mEq/L; (3) allergy or intolerance to ACEI or ARB; (4) use of ARB in the last 3 months; (5) class III or IV heart failure or angina; (6) hospitalization in the last 3 months; (7) pregnancy; (8) ongoing chemotherapy; and (9) hematuria or any clinical or laboratorial findings suggestive of associated nondiabetic glomerulopathy. The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, and all patients signed an informed consent.

Fifty-nine patients were invited to participate in the protocol. Three refused to participate, whereas 56 patients were enrolled in the study. Patients were randomized in the first day of the study, 28 being allocated to each study arm (enalapril+placebo or enalapril+losartan). The trial lasted for 8 months. The analyses showed that there was no difference in proteinuria evolution among the two treatment arms (17). After the trial follow-up period, the patients were kept in the same outpatient clinic. At this time, use of ACE inhibitor and ARB was free, according to clinical judgment. Other anti-hypertensive drugs were used according to individual needs, targeting a BP value of less than 130 × 80 mmHg. Glycated hemoglobin target was 7%, and endocrinology referral was made for those patients with persistently inadequate glycemic control. Aspirin and statins were used systematically, unless formally contraindicated.

Fasting serum and plasma, 24-hour urine, and early-morning spot urine were all collected at the beginning of the study. Urine and blood aliquots were prepared and stored at −20°C. BP was taken in the sitting position with a standard mercury sphygmomanometer after a 5-minute rest, and the average of three measurements was used in the analyses. Proteinuria was determined by sulfosalicylic acid testing, and urinary and serum creatinine concentrations were determined by the Jaffé reaction. Estimated Cockcroft-Gault creatinine clearances were calculated and corrected for 1.73 m2. A similar correction was performed for 24-hour proteinuria. Glycated hemoglobin was measured by HPLC, and all other laboratorial variables were determined using conventional laboratorial techniques. Intact parathyroid hormone (PTH; chemiluminescent substrate, Diagnostics Products Corporation Medlab; reference range (RR) = 10 to 87 pg/ml) and 25-hydroxyvitamin D (chemoluminescent assay, Dia-Sorin, RR ≥ 30 ng/ml) were measured in serum, whereas serum-intact FGF-23 was measured using a commercially available kit (ELISA assay, Kainos Lab, Japan; RR = 8.2 to 54.3 pg/ml) for the first 55 patients of the protocol.

The patients were followed prospectively until June 2009 or until the primary outcome was reached. Four patients were lost to follow-up. The composite primary outcome was defined as death, doubling of baseline serum creatinine, and/or dialysis need.

In the descriptive data, patients were classified according to categories of FGF-23 (higher or lower than median FGF-23 value). The Mann-Whitney U test was used for univariate comparisons of non-Gaussian continuous variables, t test was used for univariate comparisons of Gaussian continuous variables, and χ2 or Fisher tests were used for the categorical ones. Skewed variables were log transformed, and Spearman's correlation coefficients were calculated. Cox proportional hazard models were built to assess the relationship between FGF-23 and the composite primary outcome, even after adjustment for possible confounding variables. Finally, Kaplan-Meier curves and a log-rank test were performed to compare FGF-23 groups and the incidence of the composite primary outcome. All of the statistical analyses were done using SPSS for Windows 13.0.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the 55 patients enrolled in this study according to FGF-23 median value. Serum FGF-23 showed a significant association with proteinuria, serum creatinine, urinary fractional excretion of phosphate, male sex, and race (lower percentage of nonwhite patients in the group with higher FGF-23 value). It was also inversely and significantly related to estimated and measured creatinine clearance, serum albumin, and glycated hemoglobin. Interestingly, FGF-23 was not related to serum calcium, phosphorus, 25OH-vitamin D, intact PTH, or 24-hour urinary phosphorus in this population.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratorial characteristics of the population according to serum FGF-23 median values

| FGF-23 (n = 55) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGF-23 Value of <70 pg/ml (n = 27) | FGF-23 Value of >70 pg/ml (n = 28) | Pa | |||

| FGF-23 (pg/ml; mean/standard) | 37.9 | 21.1 | 144.3 | 63.8 | <0.0001 |

| Age (years, mean/standard) | 57.2 | 9.3 | 59.6 | 10.6 | 0.39 |

| Sex (n/% of men) | 13 | 48.1 | 21 | 75.0 | 0.05 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl; mean/standard) | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.004 |

| Estimated creatinine clearance (CG, ml/min per 1.73 m2; mean/standard) | 62.5 | 27.8 | 43.8 | 13.6 | 0.003 |

| 24-hour creatinine clearance (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 54.0 | 26.1 | 37.4 | 15.3 | 0.01 |

| 24-hour proteinuria (g/1.73 m2 per d; median/IQR) | 2.3 | 1.1 to 4.2 | 3.3 | 2.2 to 6.6 | 0.03 |

| Albumin (mg/dl; mean/standard) | 3.5 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 0.5 | 0.03 |

| SBP (mmHg; mean/standard) | 144.8 | 25.0 | 153.6 | 19.5 | 0.15 |

| DBP (mmHg; mean/standard) | 79.7 | 13.3 | 82.3 | 13.8 | 0.48 |

| BMI (mean/standard) | 24.1 | 3.5 | 24.1 | 3.4 | 0.96 |

| Potassium (mEq/L; mean/standard) | 4.6 | 0.4 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.99 |

| Glycemia (mg/dl; mean /std) | 156.5 | 72.5 | 146.8 | 60.3 | 0.59 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%; mean/standard) | 9.0 | 2.0 | 7.8 | 1.7 | 0.02 |

| Total cholesterol total (mg/dl; mean/standard) | 187.5 | 50.1 | 186.6 | 58.7 | 0.95 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl; mean/standard) | 105.1 | 44.9 | 101.1 | 51.0 | 0.76 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl; mean/standard) | 52.6 | 12.7 | 47.3 | 14.8 | 0.17 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl; median/IQR) | 144.0 | 89 to 250 | 194.0 | 120 to 284 | 0.15 |

| Calcium (mg/dl; mean/standard) | 9.5 | 0.6 | 9.2 | 0.9 | 0.10 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl; mean/standard) | 4.1 | 0.6 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 0.77 |

| PTH (pg/ml; median/IQR) | 55.0 | 32 to 93 | 78.5 | 46 to 119 | 0.14 |

| 24-hour urinary phosphorus (mg/24 h; median/IQR) | 492.0 | 424 to 642 | 549.0 | 404 to 717 | 0.43 |

| Urinary fractional excretion of phosphate (%; mean/standard) | 18.3 | 8.8 | 27.6 | 11.3 | 0.002 |

| 25OH-vitamin D (ng/mL; mean/standard) | 23.1 | 9.8 | 21.2 | 10.6 | 0.48 |

| pH (mean/standard) | 7.3 | 0.03 | 7.3 | 0.03 | 0.69 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L; mean/standard) | 25.0 | 2.4 | 24.4 | 3.6 | 0.51 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl; mean/standard) | 13.0 | 1.5 | 12.8 | 2.2 | 0.69 |

| Hematocrit (%; mean/standard) | 39.2 | 4.1 | 38.3 | 6.5 | 0.54 |

| Iron (μg/dl; mean/standard) | 83.8 | 30.4 | 76.0 | 19.2 | 0.28 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml; median/IQR) | 138.0 | 54 to 225 | 166.0 | 87 to 304 | 0.47 |

| Race (n/% of non-white) | 20 | 74.0 | 12 | 42.8 | 0.03 |

CG, Cockcroft-Gault; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

χ2 for categorical variables, t test for continuous Gaussian variables, and Mann-Whitney for continuous non-Gaussian variables.

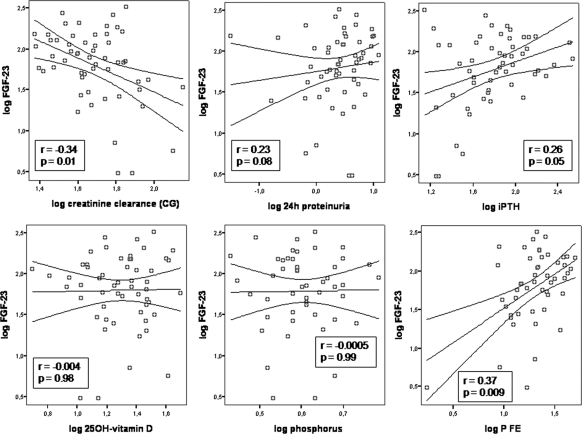

Figure 1 shows the scatter plots and correlation coefficients of log transformed serum FGF-23 values and other laboratorial variables. In this analysis, FGF-23 was significantly related only to estimated creatinine clearance, phosphate fractional excretion, and serum intact PTH. A trend of an association was seen with proteinuria, and no relationship was observed among FGF-23 and glycated hemoglobin, phosphorus, or 25OH-vitamin D.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots and correlation coefficients of serum FGF-23 and other laboratorial variables. The lines represent linear regression and 95% mean prediction interval. The boxes contain Spearman's correlation coefficients and P values. P FE, urinary fractional excretion of phosphate.

The mean follow-up time was 30.7 ± 10 months. By the censoring date, 15 events had occurred: 12 renal events (serum creatinine doubling and/or dialysis need), one patient presenting doubling of serum creatinine followed by death after 6 months, and two patients dying without need of dialysis or doubling of serum creatinine. Among the 15 events, four occurred in patients with FGF-23 values lower than 70 pg/ml, and the remaining 11 events occurred in the group with FGF-23 values of >70 pg/ml (P = 0.02). Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models (Table 2) showed that FGF-23 was an independent predictor of the primary outcome, even after adjustment for age, sex, race, estimated or 24-hour creatinine clearance, original trial treatment arm, proteinuria, serum phosphate, and intact PTH. When patients were separated according to the median estimated creatinine clearance (higher or lower than >47.6 ml/min per 1.73 m2), serum FGF-23 showed the same relation to the primary outcome in both groups (even considering a P value of 0.06 in the group with lower creatinine clearance). Interestingly, after adjustment for estimated creatinine clearance and intact PTH, each 10 pg/ml of FGF-23 increase was related to an increase of 9% in the hazard of the composite event (hazard ratio, 1.09; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.16, P = 0.02).

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazard models on the risk of the composite primary outcome

| HR | 95% CI HR | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 0.003 |

| Estimated creatinine clearance (CG) of <47.6 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | ||||

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 0.06 |

| Estimated creatinine clearance (CG) of >47.6 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | ||||

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.16 | 0.03 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 0.004 |

| age | 1.01 | 0.96 | 1.07 | 0.67 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.14 | 0.01 |

| sex (male × female) | 1.77 | 0.48 | 6.49 | 0.39 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.16 | 0.003 |

| race (white) | 1.60 | 0.54 | 4.75 | 0.40 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 0.005 |

| treatment arm (original trial) | 1.10 | 0.38 | 3.21 | 0.86 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 0.01 |

| estimated creatinine clearance (CG) | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.13 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.14 | 0.01 |

| 24-hour creatinine clearance | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.02 | 0.34 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.15 | 0.01 |

| 24-hour proteinuria | 1.31 | 1.10 | 1.57 | 0.003 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 0.003 |

| glycated hemoglobin | 0.98 | 0.75 | 1.28 | 0.89 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.02 | 1.16 | 0.01 |

| intact PTH | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.16 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 0.003 |

| phosphate | 1.71 | 0.69 | 4.24 | 0.25 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.15 | 0.02 |

| urinary fractional excretion of phosphate | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.11 | 0.04 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.02 | 1.16 | 0.02 |

| urinary fractional excretion of phosphate | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.11 | 0.15 |

| estimated creatinine clearance (CG) | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.62 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.15 | 0.02 |

| estimated creatinine clearance (CG) | 0.97 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.13 |

| 24-hour proteinuria | 1.34 | 1.10 | 1.63 | 0.004 |

| FGF-23 (per 10 pg/ml increase) | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.16 | 0.02 |

| estimated creatinine clearance (CG) | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.02 | 0.26 |

| intact PTH | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.55 |

HR, hazard ratio; CG, Cockcroft-Gault.

Finally, Kaplan-Meier curves (Figure 2) showed that FGF-23 was significantly related to the composite outcome in this population (log rank, P = 0.02). Repeating Kaplan-Meier curves for strata of baseline estimated creatinine clearance (higher and lower than median creatinine clearance value) yielded a pooled over strata log rank P value of 0.03. To further adjust for the possible confounding effect of creatinine clearance, we also performed a Kaplan-Meier curve for the residual FGF-23 (classified according to a ROC curve cut-off value) of an exponential regression of estimated creatinine clearance on FGF-23. This analysis showed a Kaplan-Meier curve (not shown) very similar to the one seen in Figure 2, with a log-rank test with a P value of 0.007, suggesting again that the relationship between FGF-23 and the primary outcome in this study is independent of the inverse relation of creatinine clearance and FGF-23.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of the incidence of the composite primary outcome according to serum FGF-23 in 55 diabetic nephropathy patients.

Discussion

Our data suggest that serum FGF-23 is related to the risk of CKD progression in macroalbuminuric DN. This relationship remained even after adjustments for the main confounding variables, such as sex, race, renal function, proteinuria, and intact PTH level. Similar data had already been shown in nondiabetic kidney disease (15). However, mineral metabolism disturbances show different patterns in diabetic and nondiabetic disease, with diabetic patients presenting more frequently lower PTH levels and adynamic bone disease in comparison with nondiabetic CKD patients. Data comparing FGF-23 behavior in these two conditions are not widely available, but our study suggests that the relationship of serum FGF-23 with CKD progression is the same in diabetic and in nondiabetic kidney disease.

Interestingly, serum FGF-23 was inversely related to glycated hemoglobin in our population. Similar findings have already been shown in hemodialysis patients (16). However, experimental studies have shown that FGF-23 knockout mice are hypoglycemic, with increased peripheral insulin sensitivity and improved subcutaneous glucose tolerance (18). On the basis of on these findings, we should expect a positive correlation between serum FGF-23 and glucose. Nevertheless, it is possible that current glycated hemoglobin does not necessarily reflect the previous burden of diabetes. In addition, it is possible that hyperglycemia might have acute effects on FGF-23 through activation of inflammatory pathways, similar to what is observed for PTH.

It is also of note that in this population serum FGF-23 was not related to serum phosphorus or 24-hour urinary excretion. Nonetheless, a positive association between serum FGF-23 and urinary fractional excretion of phosphate was observed. This is in accordance with the phosphaturic nature of FGF-23 and with the inverse relation between FGF-23 and creatinine clearance. It is possible that a current measure of serum phosphorus or 24-hour urinary phosphorus does not appropriately reflect the burden of phosphorus excess, particularly in such a diverse and dynamic condition such as advanced DN. In this sense, urinary fractional excretion seems to be a more accurate measure of phosphorus ingestion and reflects better FGF-23 phosphaturic effect. However, it is also importantly influenced by renal function, and association models for FGF-23 and urinary fractional excretion of phosphate need to be adjusted for renal function.

In our analyses, FGF-23 levels were not related to serum 25OH-vitamin D. Although it is known that FGF-23 values regulate the production of the active form of vitamin D and vice versa, it seems that FGF-23 is not a determinant of 25OH-vitamin D, at least in DN.

Whether FGF-23 actually contributes to CKD progression or is only a marker of its risk remains an important and unresolved question. Most available data on FGF-23 and the risk of mortality and cardiovascular and renal morbidity rely on epidemiologic studies. More substantial proof of a causal effect between FGF-23 and these conditions is still lacking. So far, some of the evidence suggesting that FGF-23 plays a role in cardiovascular risk comes from a knockout animal model for klotho, where a premature-aging syndrome is observed, with arteriosclerosis, osteoporosis, ectopic calcification, and shortened life span, accompanied by an increased FGF-23 level (19). It has been demonstrated that patients with CKD possess a low kidney level of klotho mRNA (20), suggesting that CKD might be a state of high FGF-23 and low klotho level. Despite the low levels of klotho, FGF-23 might bind to FGF receptors with sufficiently high affinity in conditions of very high concentration (21). If FGF-23 actively contributes to renal and cardiovascular risk, then new therapeutic strategies should be focused on the reduction and/or blockage of FGF-23.

On the other hand, some authors believe that phosphate retention, and not FGF-23, is the pathologic mechanism majorly involved in aging, glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity disturbances, and oxidative stress (22). In accordance to this theory, the generation of NaPi2a and klotho double-knockout mice, a model that presents high serum FGF-23 and calcitriol with normal serum phosphate, resulted in amelioration of premature aging-like features, suggesting that phosphate toxicity is the main cause of the premature aging seen in the klotho mice (23). In addition to that, the treatment of uremic rats with mutant FGF-23 resulted in a decrease in serum phosphate accompanied by amelioration of glomerular sclerosis (24). In this sense, FGF-23 may be a very good marker of phosphate retention, but therapeutic efforts should be maintained on phosphate restriction and on the use of phosphate binders.

Another way by which FGF-23 might influence CKD progression is by aggravating other mineral metabolism parameters that also modulate CKD progression. Animal and clinical studies suggest that FGF-23 excess causes a decrease in 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D by inhibiting α-hydroxylase activity, favoring the occurrence of severe hyperparathyroidism (25). Vitamin D deficiency is possibly involved in the progression of CKD (26), and recent small clinical trials suggest that active vitamin D administration might effect proteinuria, a surrogate end point of CKD (27,28). Similarly, PTH (4,29) has already been related to a worse evolution of CKD.

This study presents several limitations. We had no data on phosphorus intake, and we could not measure 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D. In addition, we included as events two deaths of patients who did not present a renal event (serum creatinine doubling or dialysis). This was done to increase the power of the study and considering that renal failure is an important risk factor for mortality. Most importantly, this is a study with a small sample size. Although a high rate of CKD progression was observed among our patients, with nearly 30% of the population recruited presenting the composite outcome in a mean follow-up time of 2.5 years, the absolute number of events does not allow a more powerful multivariate Cox regression model. In addition, creatinine clearance was a major confounding variable, because patients with higher serum FGF-23 values had lower creatinine clearance. However, we tried to adjust for the effect of renal function using several approaches: by entering renal function as a covariate in the Cox Regression models, by performing survival analysis after stratification according to estimated creatinine clearance, and by performing a Kaplan-Meier curve using the residual FGF-23 of a regression of estimated creatinine clearance on FGF-23. In all of the models tested, the relationship between FGF-23 and the risk of the primary outcome did not considerably change, suggesting that the effect measured is truly independent of renal function or other mineral metabolism variables.

In conclusion, our data suggest that serum FGF-23 is a significant independent predictor of renal outcome in patients with macroalbuminuric DN. Further studies should clarify whether this relationship is causal and whether FGF-23 should be a new target for therapeutic measures aiming at CKD prevention.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. Adeney KL, Siscovick DS, Ix JH, Seliger SL, Shlipak MG, Jenny NS, Kestenbaum BR: Association of serum phosphate with vascular and valvular calcification in moderate CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 381–387, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, Yoon C, Gales B, Sider D, Wang Y, Chung J, Emerick A, Greaser L, Elashoff RM, Salusky IB: Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 342: 1478–1483, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodriguez-Benot A, Martin-Malo A, Alvarez-Lara MA, Rodriguez M, Aljama P: Mild hyperphosphatemia and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 68–77, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, Ofsthun N, Lowrie EG, Chertow GM: Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2208–2218, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Menon V, Greene T, Pereira AA, Wang X, Beck GJ, Kusek JW, Collins AJ, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ: Relationship of phosphorus and calcium-phosphorus product with mortality in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 455–463, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, Gao Z, Curhan G: Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation 112: 2627–2633, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dhingra R, Sullivan LM, Fox CS, Wang TJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr., Gaziano JM, Vasan RS: Relations of serum phosphorus and calcium levels to the incidence of cardiovascular disease in the community. Arch Intern Med 167: 879–885, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foley RN, Collins AJ, Herzog CA, Ishani A, Kalra PA: Serum phosphorus levels associate with coronary atherosclerosis in young adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 397–404, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, Smith K, Lee H, Thadhani R, Juppner H, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 359: 584–592, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jean G, Terrat JC, Vanel T, Hurot JM, Lorriaux C, Mayor B, Chazot C: High levels of serum fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 are associated with increased mortality in long haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2792–2796, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Parker BD, Schurgers LJ, Brandenburg VM, Christenson RH, Vermeer C, Ketteler M, Shlipak MG, Whooley MA, Ix JH: The associations of fibroblast growth factor 23 and uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein with mortality in coronary artery disease: The Heart and Soul Study. Ann Intern Med 152: 640–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gutierrez OM, Januzzi JL, Isakova T, Laliberte K, Smith K, Collerone G, Sarwar A, Hoffmann U, Coglianese E, Christenson R, Wang TJ, deFilippi C, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation 119: 2545–2552, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mirza MA, Larsson A, Lind L, Larsson TE: Circulating fibroblast growth factor-23 is associated with vascular dysfunction in the community. Atherosclerosis 205: 385–390, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mirza MA, Hansen T, Johansson L, Ahlstrom H, Larsson A, Lind L, Larsson TE: Relationship between circulating FGF23 and total body atherosclerosis in the community. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 3125–3131, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fliser D, Kollerits B, Neyer U, Ankerst DP, Lhotta K, Lingenhel A, Ritz E, Kronenberg F, Kuen E, Konig P, Kraatz G, Mann JF, Muller GA, Kohler H, Riegler P: Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) predicts progression of chronic kidney disease: The Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease (MMKD) Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2600–2608, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kojima F, Uchida K, Ogawa T, Tanaka Y, Nitta K: Plasma levels of fibroblast growth factor-23 and mineral metabolism in diabetic and non-diabetic patients on chronic hemodialysis. Int Urol Nephrol 40: 1067–1074, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Titan SM, VJ, Barros RT, Zatz R: The effect of enalapril and losartan association therapy on proteinuria progression in advanced diabetic nephropathy: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 28A, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hesse M, Frohlich LF, Zeitz U, Lanske B, Erben RG: Ablation of vitamin D signaling rescues bone, mineral, and glucose homeostasis in Fgf-23 deficient mice. Matrix Biol 26: 75–84, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Kaname T, Kume E, Iwasaki H, Iida A, Shiraki-Iida T, Nishikawa S, Nagai R, Nabeshima YI: Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 390: 45–51, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koh N, Fujimori T, Nishiguchi S, Tamori A, Shiomi S, Nakatani T, Sugimura K, Kishimoto T, Kinoshita S, Kuroki T, Nabeshima Y: Severely reduced production of klotho in human chronic renal failure kidney. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 280: 1015–1020, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu X, Ibrahimi OA, Goetz R, Zhang F, Davis SI, Garringer HJ, Linhardt RJ, Ornitz DM, Mohammadi M, White KE: Analysis of the biochemical mechanisms for the endocrine actions of fibroblast growth factor-23. Endocrinology 146: 4647–4656, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuro-o M: A potential link between phosphate and aging: Lessons from Klotho-deficient mice. Mech Ageing Dev 131: 270–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ohnishi M, Razzaque MS: Dietary and genetic evidence for phosphate toxicity accelerating mammalian aging. FASEB J 24: 3562–3571, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kusano K, Saito H, Segawa H, Fukushima N, Miyamoto K: Mutant FGF23 prevents the progression of chronic kidney disease but aggravates renal osteodystrophy in uremic rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 55: 99–105, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gutierrez O, Isakova T, Rhee E, Shah A, Holmes J, Collerone G, Juppner H, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor-23 mitigates hyperphosphatemia but accentuates calcitriol deficiency in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2205–2215, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agarwal R: Vitamin D, proteinuria, diabetic nephropathy, and progression of CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1523–1528, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alborzi P, Patel NA, Peterson C, Bills JE, Bekele DM, Bunaye Z, Light RP, Agarwal R: Paricalcitol reduces albuminuria and inflammation in chronic kidney disease: A randomized double-blind pilot trial. Hypertension 52: 249–255, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fishbane S, Chittineni H, Packman M, Dutka P, Ali N, Durie N: Oral paricalcitol in the treatment of patients with CKD and proteinuria: A randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 647–652, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levin A, Djurdjev O, Beaulieu M, Er L: Variability and risk factors for kidney disease progression and death following attainment of stage 4 CKD in a referred cohort. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 661–671, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]