Summary

Background and objectives

Chronic pain and psychiatric disorders are common in dialysis patients, but the extent to which opioids and benzodiazepines are used is unclear. We conducted a systematic review to determine the: (1) prevalence of opioid and benzodiazepine use among dialysis patients; (2) reasons for use; (3) effectiveness of symptom control; and (4) incidence of adverse events.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Two authors reviewed all relevant citations in MEDLINE/EMBASE/CINAHL/BIOSIS Previews/Cochrane and hand-searched bibliographies. Studies after 1990 reporting prevalence estimates for opioid and/or benzodiazepine use in ≥50 dialysis patients were included.

Results

We identified 15 studies from 12 countries over 1995 to 2006. Sample size ranged from 75 to 12,782. Prevalence of opioid and benzodiazepine use was variable, ranging from 5 to 36% (95% CI, 4.1 to 45.5%; n = 10) and 8 to 26% (95% CI, 7.1 to 27.3%; n = 9), respectively. Prevalence was positively correlated with years on dialysis. Five studies reported on the same cohorts but gave different prevalence estimates. One study verified medication use through patient interviews. Reasons for use were reported in one study. Effectiveness of pain control varied from 17 to 38%, and 72 to 84% of patients with significant pain had no analgesia (n = 2). No study rigorously examined for adverse events.

Conclusions

The prevalence of opioid and benzodiazepine use in dialysis patients is highly variable between centers. Further information is needed regarding the appropriateness of these prescriptions, adequacy of symptom control, and incidence of adverse effects in this population.

Introduction

Patients with ESRD on dialysis have a high burden of comorbid disease and markedly reduced quality of life compared with both the general population (1–4) and with patients with other chronic disease states (5). Of all symptoms reported by patients with ESRD, pain is the most common (6). Recent reviews show that 47% of patients with ESRD experience pain (6), and this can be moderate to severe in 82% (7). The etiology of the pain is multifactorial, related to comorbidities (peripheral vascular disease, osteoarthritis, etc.), complications of renal failure (bone disease, calciphylaxis, peripheral neuropathy, etc.), and the dialysis procedure (needle insertion, osmolar shift cramps, dialysate infusion pain, etc.).

Despite its high prevalence, there is little information on whether chronic pain in ESRD is adequately treated. Opioids may be underutilized in patients with renal failure because of concerns about reduced clearance and increased adverse effects (8). Conversely, they may be overutilized for nonsomatic pain that may be more appropriately treated with other agents.

In addition, pain often coexists with depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Almost two of every five dialysis patients experience troubled sleep (6), and 38 to 45% suffer anxiety (6). Treatment of these conditions often results in the concomitant use of benzodiazepines with opioids, potentially increasing side effects. Recommendations regarding the appropriate use of benzodiazepines in ESRD are lacking (9).

To assess the current state of knowledge and inform future research, we conducted a systematic review of the literature on the use of opioids and benzodiazepines in patients receiving dialysis. We sought to determine the prevalence of opioid and benzodiazepine use in ESRD, reasons for their prescription, effectiveness of symptom control, and associated adverse events.

Materials and Methods

Finding Relevant Studies

We performed a comprehensive search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, BIOSIS Previews, and Cochrane Library bibliographic databases from their date of inception to August 1, 2010 for relevant citations in any language. Longitudinal and cross-sectional cohort studies reporting the prevalence of benzodiazepine or opioid prescriptions in ≥50 patients receiving hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis were included. Randomized trials were not eligible because they do not give reliable estimates of prevalence. Two authors independently evaluated eligibility, and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

An experienced librarian reviewed the search strategy, which included the terms benzodiazepine, opioid, narcotic, end-stage-renal-disease/ESRD, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and dialysis. We pilot tested and modified the search strategy iteratively until all articles of known relevance were captured. All of the articles citing included articles as per the Institute for Scientific Information Science Citation Index were reviewed, and we hand-searched the reference lists of the included articles.

Data Abstraction

Using standardized forms, two authors (AW and RR) independently abstracted data from eligible articles on study design, location, baseline patient characteristics, prevalence of opioid and benzodiazepine use, reasons for prescription, effectiveness of symptom control, and adverse events. The authors independently reviewed articles for methodological quality using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa-Scale for quality assessment of observational studies (10) (Table 1). All of the data were reviewed by a third author (RS), and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Table 1.

Quality of included studies

| Number of Studies (Total = 15) | |

|---|---|

| Representativeness | |

| study sample represents the community of dialysis patients well | 13 (87%) |

| study collects data prospectively | 13 (87%) |

| comparison cohorts, if present, are drawn from the same source | 3 (20%)a |

| study reports clear inclusion and exclusion criteria | 14 (93%) |

| study measures actual use of opioids and benzodiazepines (versus prescription) | 1 (7%) |

| study includes prevalent and incident patients | 6 (40%) |

| all patients in the study are accounted for, and attrition was <20% | 4 (27%) |

| Results | |

| study reports baseline characteristics (e.g., age, gender, comorbidities) | 14 (93%) |

| study reports reasons for prescription of opioids and benzodiazepines | 1 (7%) |

| study reports effectiveness of opioids and benzodiazepines | 2 (7%) |

| adverse events associated with opioid/benzodiazepine use reported | 7 (47%) |

Comparison cohort not applicable in the other 12 studies.

Statistical Analysis

Agreement between authors regarding article inclusion was assessed using kappa. Baseline characteristics, prevalence estimates, and adverse events for each study population were compiled in tabular format. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the proportion of dialysis patients using opioids and benzodiazepines in each study were calculated using the Wilson score method (11). Where multiple studies appeared to report on the same cohort of patients, estimates from the study with the most complete data or highest methodological quality were included in the prevalence estimates. χ2 tests were used to assess between-study heterogeneity, and the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation caused by heterogeneity rather than chance, was calculated (12). Given significant clinical and statistical heterogeneity, prevalence estimates were not pooled. All of the computations were performed in R2.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study Selection

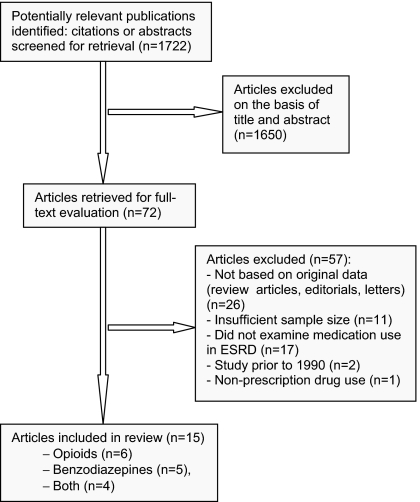

Our search strategy yielded >1700 citations, of which 72 full-text articles were retrieved for further evaluation on the basis of abstract and title. Fifteen articles met inclusion criteria (1,7,13–25) (Figure 1). Agreement beyond chance between the two authors for article inclusion was good (kappa = 0.79).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included studies.

Quality of Included Studies

Inter-rater reliability in the assessment of methodological quality criteria was good (Table 1). Only four studies were specifically designed to examine opioid and/or benzodiazepine use (7,13–15). The data were collected prospectively in all studies, and one retrieved data from an administrative database (16). Patient baseline characteristics and eligibility criteria were reported in the majority of studies, but few described the proportions of patients with missing data. Twelve studies reported on prevalent cross-sections of patients receiving hemodialysis (7,13–15,18–25), whereas three restricted inclusion to patients starting hemo- or peritoneal dialysis in the last 3 months (1,16,17). One opioid study restricted prevalence estimates to the 50% of patients reporting ongoing pain (7). One study verified actual medication use through patient interviews (18), and two reported the effectiveness of symptom control (7,13). Ten studies examined for associations between opioids or benzodiazepines and at least one potential adverse effect (14,16–17,19–20,22,23), but none rigorously examined for these.

Patterns of Opioid Use

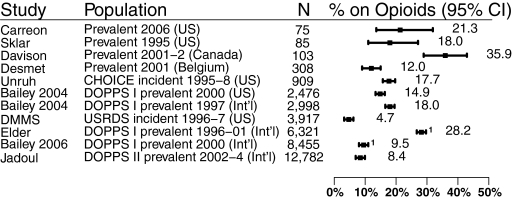

Ten studies described opioid use in dialysis patients (1,7,13,17,19–21,23–25). Five were from the United States (1,13,17,24,25), one was from Canada (7), and one was from Belgium (19). The remaining three included cross-sections of patients from between 7 and 12 countries (Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study [DOPPS] I and II) (20,21,23). Two of the DOPPS I studies reported on similar cohorts of patients (20,21) (Figure 2). In total, there were >26,000 unique patients from 1995 to 2004, and >90% of these patients were receiving hemodialysis. Patient baseline characteristics from all of the studies are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of opioid use. 1 indicates studies that overlap in time and population.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of study populations

| Study | Period | Country | Population | Dialysis Units | N | Dialysis Duration (years) | Mean Age (years) | Male (%) | Comorbidities |

Benzodiazepine Use |

Opioid Use |

Upper 95% CI | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black (%) | HT | CVD | PVD | DB | N | % | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | N | % | Lower 95% CI | |||||||||||

| Opioids | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elder (2008) | 1996–2001 | Intl. | DOPPS I prev. | 308 | 6321 | 3.15 | 59 ± 14.5 | 58 | 15 | 72.5 | 14.0 | 19.6 | 30.0 | 1782 | 28.2 | 27.1 | 29.3 | |||||

| Bailey (2006) | 2000 | Intl. | DOPPS I prev. | 308 | 8455 | 4.9 ± 5.4 | 60 ± 14.7 | 57 | 38 | 73.1 | 15.4 | 21.3 | 32.9 | 803 | 9.5 | 8.9 | 10.1 | |||||

| Bailey (2004) | 1997 | US | DOPPS I prev. | 142 | 2998 | 3.4 ± 3.8 | 60.6 ± 15.5 | 53 | 38 | 84.1 | 18.3 | 26.2 | 46.2 | 538 | 18.0 | 16.7 | 19.4 | |||||

| 2000 | US | DOPPS I prev. | 142 | 2476 | 3.4 ± 3.8 | 60.6 ± 15.5 | 53 | 38 | 84.1 | 18.3 | 26.2 | 46.2 | 368 | 14.9 | 13.5 | 16.3 | ||||||

| Desmet (2005) | 2001 | Belgium | Cross-section | 7 | 308 | 2.3 | 67 ± 13.9 | 56 | — | — | 12.0 | — | 27.3 | 37 | 12.0 | 8.8 | 16.1 | |||||

| Davison (2003) | 2001–2002 | Canada | 4 | 103 | 3.75 ± 3.2 | 60 ± 15.9 | 58 | 1.5 | 55.6 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 37.1 | 37 | 35.9 | 27.3 | 45.5 | ||||||

| Carreon (2008) | 2006 | US | Cross-section | 3 | 75 | 4.4 ± 5.8 | 59 ± 14 | 67 | — | — | 15.0 | 15.0 | 53.0 | 16 | 21.3 | 13.6 | 31.9 | |||||

| Both | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sklar (1996) | 1995 | US | Cross-section | 1 | 85 | 2.38 | 60.5 ± 16.5 | 59 | 6 | — | — | — | 36.4 | 22 | 25.9 | 17.8 | 36.1 | 15 | 18.0 | 11.0 | 27.1 | |

| Unruh (2006)b | 1995–1998 | US | CHOICE incident | 81 | 909 | 0.25 | 57.8 ± 14.8 | 53 | 27 | 121 | 13.3 | 11.3 | 15.7 | 161 | 17.7 | 15.4 | 20.3 | |||||

| DMMS (1998)a | 1996–1997 | US | USRDS incident | 1035 | 3917 | 0.16 | 59 ± 16 | 53 | 28 | >29 | — | — | >43 | 310 | 7.9 | 7.1 | 8.8 | 185 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 5.4 | |

| Jadoul (2006) | 2002–2004 | Intl. | DOPPS II prev. | 320 | 12782 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2171 | 17.0 | 16.3 | 17.6 | 1078 | 8.4 | 8.0 | 8.9 | |

| Benzodiazepines | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winkelmayer (2007)c | 1996–1997 | US | USRDS incident | 1035 | 3630 | 0.16 | 58.5 ± 15.6 | 54 | 29 | 71.0 | 10.0 | 17.3 | 48.6 | 408 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 12.3 | |||||

| Manley (2004) | 2003 | US | DCI cross-section | 200 | 10474 | 3.73 ± 4.0 | 60.2 ± 15.6 | 52 | 45 | >26.6 | — | — | >40.1 | 2765 | 26 | 25.6 | 27.3 | |||||

| Manley (2000) | 1999 | US | Cross-section | 2 | 238 | 2.83 ± 2.8 | 59.5 ± 16 | 53 | 21.0 | — | — | 28.0 | 32 | 13.4 | 9.7 | 18.4 | ||||||

| Fukuhara (2006) | 2002–2004 | Intl. | DOPPS II prev. | >300 | 5122 | 869 | 17.0 | 16.0 | 18.0 | |||||||||||||

| 2002–2004 | Japan | DOPPS II prev. | 59 | 1584 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 308 | 19.4 | 17.6 | 21.4 | ||||||

| Bailey (2007) | 1999 | Intl. | DOPPS I prev. | 307 | 4924 | 5.27 ± 5.6 | 58.9 ± 14.5 | 58 | 17 | 72.2 | 13.8 | 19.5 | 31.0 | 741 | 15.0 | 14.1 | 16.1 | |||||

| 2002–2004 | Intl. | DOPPS II prev. | 320 | 7760 | 5.19 ± 5.6 | 61.7 ± 14.4 | 58 | 9 | 77.0 | 16.3 | 24.9 | 32.5 | 1536 | 20.2 | 19.3 | 21.1 | ||||||

HT, hypertension; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; DB, diabetes; Intl., international; prev., prevalent.

1919 peritoneal dialysis patients.

228 peritoneal dialysis patients.

1558 peritoneal dialysis patients.

The prevalences of opioid use in individual studies were variable and ranged from 5% (95% CI, 4.1 to 5.4%) to 36% (95% CI, 27.3 to 45.5) across unique cohorts. The variability among studies was larger than would be expected by chance alone (P < 0.001, I2 = 98%). Eliminating studies that restricted inclusion to those with pain (7) or incident patients (1,16,17) did not narrow the prevalence range substantially (8 to 21%; 95% CI, 7.1 to 23.5%). Interestingly, estimates that appeared to be obtained from the same cohort of patients were not always similar. Bailie et al. (21) reported a prevalence of 9% (95% CI, 8.9 to 10.1%) in DOPPS I from 1996 to 2001, whereas Elder et al. (20) reported an estimate of 28% (95% CI, 27.1 to 29.3%) from the same database as of 2000. These variable prevalence estimates did not correlate with time period, dialysis vintage, or sample size (data not shown).

The most commonly prescribed narcotic was propoxyphene in combination with acetaminophen in a United States study (13), as compared with codeine and oxycodone in a Canadian study (7). Duration of narcotic use averaged >12 months for 50% of patients and >36 months for another 25% (13).

The reasons for opioid use were examined only in the Canadian study, with musculoskeletal pain found to be most common (65%), followed by dialysis procedure-related pain (14%), peripheral neuropathy (15%), and peripheral vascular disease (10%) (7). Effectiveness of pain control with opioids varied between the two studies examining this outcome. Davison (7) found 38% (95% CI, 29.1 to 47.5%) of patients on weak or strong opioids still reporting pain of moderate to severe intensity within the last 24 hours, whereas Bailie's estimate approached 17% (95% CI, 13.6 to 21.3%) for similar intensity pain experienced over the last 4 weeks (13). Opioid use was positively correlated with time on dialysis (odds ratio [OR] 1.04 per year, P < 0.0001) (13). It was also more likely among women (OR 1.11, P < 0.0001) and patients with cardiovascular disease (1.21, P = 0.008), cancer (OR 1.27, P = 0.02), and psychiatric disease (1.37, P < 0.0001) (13).

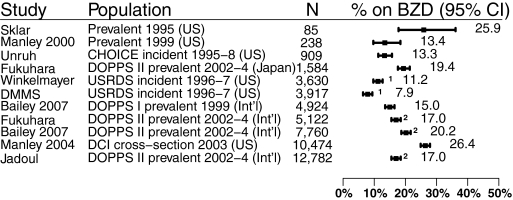

Patterns of Benzodiazepine Use

Nine studies reported on benzodiazepine use in patients on dialysis (1,14–18,22–24). Six of these were from the United States (1,15–18,24), and three were international cross-sections from DOPPS I and II (14,22,23). Three studies reported on the same cohort of DOPPS I patients (14,22,23), whereas two reported on Dialysis Mortality and Morbidity Study Wave 2 patients (1,16). In total, there were >33,000 unique patients from 1995 to 2004, and approximately 90% of these patients were receiving hemodialysis. Patient baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

There was significant clinical and statistical heterogeneity between studies on the prevalence of benzodiazepine use (P < 0.001, I2 = 99%) (Figure 3). In the three unique studies of incident ESRD populations, benzodiazepine use ranged from 8% (95% CI, 7.1 to 8.8%) to 13% (95% CI, 11.3 to 15.7%) (1,16,17). The prevalence across the remaining studies ranged from 13% (95% CI, 9.7 to 18.4%) to 26% (95% CI, 25.6 to 27.3%) (14–15,18,22–24). We found no correlation between prevalence and time period or sample size.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of benzodiazepine use. 1 and 2 indicate studies that overlap in time and population.

None of the studies examined the reasons for benzodiazepine use or the effectiveness of symptom control. A Japanese study commented on clinically depressed ESRD patients being twice as likely as those in other countries to be prescribed benzodiazepines (32.3% versus 15.7%) (14). The most commonly prescribed benzodiazepines in one study were temazepam, lorazepam, alprazolam, and clonazepam (16). Dialysis patients who used benzodiazepines were more likely to be female (53% versus 45%, P = 0.002), Caucasian (77% versus 60%, P < 0.001), and have lung disease (OR = 1.43; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.98) and less likely to have cerebrovascular disease (OR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.98) (16).

Adverse Effects of Opioid and Benzodiazepine Use

No study rigorously examined for adverse effects from opioid or benzodiazepine use in dialysis patients. However, both opioids and benzodiazepines were reported to be weakly associated with poor sleep quality (17,20). Benzodiazepines were also associated with reduced sexual pleasure and arousal (22). Two studies reported a significant association between benzodiazepine prescription and death in adjusted analyses (14,16), whereas opioids were associated with an increased risk of falls (19) and fractures (23). These relationships, however, are not necessarily causal (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adverse events associated with opioid and benzodiazepine use

| Risk of Outcome |

Study | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| With Opioids | With Benzodiazepines | ||

| Poor sleep quality | 1.55 (P < 0.0001)a | 1.59 (P < 0.0001)a | Elder (2008) |

| 1.22 (95% CI: 0.88 to 1.69)a | 1.67 (95% CI: 1.15 to 2.44)a | Unruh (2006) | |

| Sexual dysfunction (pleasure) | — | 1.26 (P = 0.0078)a | Bailie (2007) |

| Sexual dysfunction (arousal) | — | 1.24 (P = 0.0134)a | Bailie (2007) |

| Hip fracture | — | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0)c | Winkelmayer (2007) |

| 1.55 (P < 0.05) | 1.19 (P = 0.03) | Jadoul (2006) | |

| Any fracture | 1.67 (0.01<P ≤ 0.05) | 1.31 (P = 0.03) | Jadoul (2006) |

| Falls | 3.7 (P < 0.001)a,b | — | Desmet (2005) |

| Hospitalization | — | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | Fukuhara (2006) |

| Mortality | — | 1.27 (1.01 to 1.59, P < 0.04) | Fukuhara (2006) |

| 1.15 (1.02 to 1.31)b | Winkelmayer (2007) | ||

Odds ratios.

Unadjusted odds ratio.

Hazard ratios (all others are relative risk values).

Discussion

In this systematic review with more than 26,000 unique ESRD patients, the prevalence of opioid use was highly variable, ranging from 5 to 36% (95% CI, 4.1 to 45.5%). In comparison, United States pharmacy claims suggest that between 17 and 18% of the general population uses opioids (26), and studies of United States veterans place estimates as high as 33% (27). The reported opioid use in ESRD patients is much lower than we expected, considering that patients on dialysis report significantly higher pain and worse physical functioning than the general population (1–4,28,29). Individual studies in our review confirm that pain is inadequately managed in this population (7,13,25). This issue deserves attention from nephrologists, because inadequate pain control not only results in poor quality of life but may ultimately lead certain patients to withdraw from dialysis.

One reason that opioids are underutilized in patients receiving dialysis may be physician concerns regarding adverse effects. Opioids may exacerbate symptoms of chronic kidney disease (e.g. nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and constipation) and those attributed to hemodialysis (e.g. orthostatic hypotension and impaired cognition) (8). They may also cause more serious side effects including central nervous system depression, cardiorespiratory depression, and physical and psychologic dependence (8). The potential for adverse effects is compounded in dialysis patients because of reduced renal clearance of active metabolites, the uremic environment, and the presence of multiple comorbidities. Different classes of opioids may have differential effects in this regard (30,31), but practitioners may not be aware of these nuances. A fear of potential medico-legal ramifications may reinforce physicians' reluctance to prescribe opioids. A review of the recent April 2009 Canadian Medical Protective Association Risk Identification paper revealed 49 law suits launched in Canada between 2000 and 2007 because of alleged inappropriate opioid prescription and associated adverse events, but only one of these decided against the prescribing physician (32). Fears of litigation may be unfounded in Canada, but the same may not hold true in other jurisdictions.

Although opioids may be underutilized in some patients, they may be prescribed inappropriately in others. The reasons for prescription of opioids in ESRD patients are not always clear, as was suggested by our review. We found only one study that reported reasons for opioid prescription; almost half of the patients had conditions that may not respond to opioids (7). Attempted treatment of perceived pain from conditions such as restless legs and neuropathy with opioids rather than more appropriate agents such as gabapentin could result in continued functional limitation of patients and high levels of undertreated pain.

There are no clear guidelines or randomized trials on the appropriate management of chronic pain in ESRD. This is likely the major factor contributing toward both the under- and overprescription of opioids in this population (7,8,13,33). The World Health Organization recommendations for opioid therapy in acute and chronic malignant pain exist, but it is uncertain whether these can be extrapolated to nonmalignant pain and to patients with ESRD (34,35). The need for specific guidelines to treat pain in ESRD is paramount, given the potential for increased adverse effects discussed above. Non-ESRD-specific conditions such as fatigue, pain, and depression are as prevalent as ESRD-specific conditions (anemia, renal osteodystrophy, access, adequacy, etc.) and thus are deserving of equal attention by guideline committees (36). In fact, the former may be more important to patients than the latter. Furthermore, randomized controlled trials (RCT) assessing the efficacy and safety of opioids in ESRD are needed to inform such guideline development. Although our review included only cohort studies, during our search we were struck by the paucity of RCTs in this field. In fact, we could find no RCTs studying the most commonly prescribed opioids in ESRD. Currently, one group is attempting to address this deficiency (37), but more trials are needed.

The consequences of undermanaged pain have the potential to exacerbate other conditions highly prevalent in ESRD, including insomnia, restlessness, depression, and anxiety. This may result in the use of benzodiazepines for symptom control with further risks of adverse events. Although the use of benzodiazepines in the general population is between 2 and 9% (38–40), the use of these agents appears to be much higher in ESRD. In our review, we found the prevalence of benzodiazepine use to be from 8 to 26% (95% CI, 7.1 to 27.3%). This review also suggests that the use of benzodiazepines increases with time on dialysis, because we found that the prevalence in incident patients was only 8 to 13% (95% CI, 7.1 to 15.7%) (1,16,17). Prescription of benzodiazepines has also become more common in recent years. United States Medicare data show that although there were no significant changes in benzodiazepine prescription frequency among ESRD patients between 1993 and 1997 (1), there was a more than three-fold increase between 1998 and 2003 (8% in 1998 versus 26% in 2003) (18,41). The high prevalence of chronic benzodiazepine use may be appropriate to control anxiety and restlessness or less appropriate to treat insomnia. Surprisingly, no studies systematically examined the reasons for use of benzodiazepines in ESRD. One study in our review suggested that benzodiazepines were being inappropriately used to control depressive symptoms in ESRD patients, a practice associated with increased mortality (14). Guidelines on the appropriate use of benzodiazepines in ESRD are thus also needed.

This review highlights a shortage of quality studies examining opioid and benzodiazepine use in ESRD. Only four studies (7,13–15) were specifically designed to examine drug use in dialysis patients. The remainders were large trials of patients from registries that incidentally collected limited data on medication use. Only one study confirmed patient consumption of medications (18), whereas others relied solely on prescription as a surrogate for actual drug use. Less than half reported adverse effects. Included studies were also subject to high attrition rates and showed discrepancies in reported prevalences between studies using the same cohorts of patients, not accounted for by time period, dialysis vintage, or sample size (Figures 2 and 3).

There are limitations to this review. We created a modified version of an existing scale for establishing the methodological quality of included observational studies, because no widely accepted scale exists. Furthermore, studies from different centers used variable methods of data collection and collected data over multiple time intervals, resulting in large variability in prevalences between studies (opioid and benzodiazepine studies, I2 = 98 and 99%, respectively, P < 0.001). There were also no studies representing patients from Africa, India, China, the Middle East, or South America, emphasizing gaps in our understanding of global trends in medication use in ESRD.

Conclusions

Inadequately treated pain in ESRD patients is a prognostically important problem that remains poorly understood. Nephrologists are ultimately responsible for treating symptoms in dialysis patients, whether these symptoms are related to ESRD or comorbid disease. Thus, addressing knowledge gaps in this field lies within the purview of the nephrologist. More information is needed on the true prevalence, etiologies, and factors associated with inadequately treated pain and its related symptoms in ESRD. In addition, our review suggests that detailed examination of physician prescription patterns, reasons for use or nonuse of opioids and benzodiazepines, appropriateness of these prescriptions, adequacy of symptom control, and adverse effects in patients with ESRD is required. Such information can be used to guide the development of programs and practice recommendations to improve the management of chronic pain and associated symptoms in ESRD.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Ahraaz Wyne was supported by a Research Award through the Schulich Research Opportunities Program and by the London Kidney Clinical Research Unit. Dr. Suri was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Randomized Controlled Trials Mentorship Award. We would like to thank Dr. Amit Garg and Ms. Ann Young for their assistance with this study.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. United States Renal Data System: 1998 Annual Data Report: Medication use among dialysis patients in the DMMS. Am J Kidney Dis 32: S60–S68, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Merkus MP, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Stevens P, Krediet RT: Quality of life in patients on chronic dialysis: Self-assessment 3 months after the start of treatment: The Necosad Study Group. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 584–592, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Valderrabano F, Jofre R, Lopez-Gomez JM: Quality of life in end-stage renal disease patients. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 443–464, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walters BA, Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Fridman M, Carter WB: Health-related quality of life, depressive symptoms, anemia, and malnutrition at hemodialysis initiation. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 1185–1194, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, Haunstetter A, Zugck C, Herzog W: Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: Comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart 87: 235–241, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murtagh FE, Eddington-Hall J, Higginson IJ: The prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: A systematic review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 82–99, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davison SN: Pain in hemodialysis patients: Prevalence, etiology, severity, and analgesic use. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 1239–1247, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kurella M, Bennett WM, Chertow GM: Analgesia in patients with ESRD: A review of available evidence. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 217–228, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Ciarcia J, Peterson R, Kliger AS, Finkelstein FO: Identification and treatment of depression in a cohort of patients maintained on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 1011–1017, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wells GA, Shea B, Peterson J, Welch V, O'Connell D, Tugwell P: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses: Beyond the basics: Improving quality and impact. Proceedings of the 3rd Symposium on Systematic Reviews, Oxford, UK, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Newcombe RG: Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: Comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 17: 857–872, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Higgins JPT, Thompson JG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analysis. BMJ 327: 557–560, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bailie GR, Mason NA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Gillespie BW, Young EW: Analgesic prescription patterns among hemodialysis patients in the DOPPS: Potential for underprescription. Kidney Int 65: 2419–2425, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fukuhara S, Green J, Albert J, Mihara H, Pisoni R, Yamazaki S: Symptoms of depression, prescription of benzodiazepines, and the risk of death in hemodialysis patients in Japan. Kidney Int 70: 1866–1872, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manley HJ, Cannella CA, Bailie GR, St. Peter WL: Medication related problems in ambulatory hemodialysis patients: A pooled analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 669–680, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winkelmayer WC, Mehta J, Wang PS: Benzodiazepine use and mortality of incident dialysis patients in the United States. Kidney Int 72: 1388–1393, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Unruh ML, Buysse DJ, Dew MA, Evans IV, Wu AW, Fink NE: Sleep quality and its correlates in the first year of dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 802–810, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Manley HJ, Bailie GR, Grabe DW: Comparing medication use in two hemodialysis units against national dialysis databases. Am J Health Syst Pharm 57: 902–906, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Desmet C, Beguin C, Swine C, Jadoul M: Falls in hemodialysis patients: Prospective study of incidence, risk factors and complications. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 148–153, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elder SJ, Pisoni RL, Akizawa T, Fissell R, Andreucci VE, Fukuhara S: Sleep quality predicts quality of life and mortality risk in haemodialysis patients: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 998–1004, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bailie GR, Mason NA, Elder SJ, Andreucci VE, Greenwood RN, Akiba T: Large variations in prescriptions of gastrointestinal medications in hemodialysis patients on three continents: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Hemodial Int 10: 180–188, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bailie GR, Elder SJ, Mason NA, Asano Y, Cruz JM, Fukuhara S: Sexual dysfunction in dialysis patients treated with antihypertensive or antidepressive medications: Results from the DOPPS. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1163–1170, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jadoul M, Albert JM, Akiba T, Akizawa T, Arab L, Bragg-Gresham JL: Incidence and risk factors for hip or other bone fractures among hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int 70: 1358–1366, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sklar AH, Riesenberg LA, Silber AK, Ahmed W, Ali A: Postdialysis fatigue. Am J Kindey Dis 28: 732–736, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carreon M, Fried LF, Palevski PM, Kimmel PL, Arnold RM, Weisbord SD: Clinical correlates and treatment of bone/joint pain and difficult with sexual arousal in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Hemodial Int 12: 268–274, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Williams RE, Sampson TJ, Kalilani L, Wurzelmann JI, Janning SW: Epidemiology of opioid pharmacy claims in the United States. J Opioid Manag 4: 145–152, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Clark JD: Chronic pain prevalence and analgesic prescribing in a general medical population. J Pain Symptom Manage 23: 131–137, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blake C, Codd MB, Cassidy A, O'Meara YM: Physical function, employment and quality of life in end-stage renal disease. J Nephrol 13: 142–149, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Peterson RA, Switzer GE: Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2487–2494, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chan GL, Matzke GR: Effects of renal insufficiency on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of opioid analgesics. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 21: 773–783, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Niscola P, Scaramucci L, Vischini G, Giovannini M, Ferrannini M, Massa P, Tatangelo P, Galletti M, Palumbo R: The use of major analgesics in patients with renal dysfunction. Curr Drug Targets 11: 752–758, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. The Canadian Medical Protective Agency: Adverse Events: Physician Prescribed Opioids, RI0915-E, Toronto, ON, Canada, CMPA, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Portenoy RK: Opioid therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain: A review of the critical issues. J Pain Symptom Manage 11: 203–217, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barakzoy AS, Moss AH: Efficacy of the world health organization analgesic ladder to treat pain in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3198–3203, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Launay-Vacher V, Karie S, Fau JB, Izzedine H, Deray G: Treatment of pain in patients with renal insufficiency: The World Health Organization three-step ladder adapted. J Pain 6: 137–148, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Henrich WL, Agodoa LE, Barrett B, Bennett WM, Blantz RC, Buckalew VM, Jr: Analgesics and the kidney: Summary and recommendations to the Scientific Advisory Board of the National Kidney Foundation from an Ad Hoc Committee of the National Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 162–165, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weisbord SD, Shields AM, Mor MK, Sevick MA, Homer M, Peternel J, Porter P, Rollman BL, Palevsky PM, Arnold RM, Fine MJ: Methodology of a randomized clinical trial of symptom management strategies in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis: The SMILE Study. Contemp Clin Trials 31: 491–497, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kassam A, Patten SB: Hypnotic use in a population-based sample of over thirty-five thousand interviewed Canadians. Popul Health Metr 4: 15–19, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lagnaoui R, Depont F, Fourrier A, Abouelfath A, Begaud B, Verdoux H: Patterns and correlates of benzodiazepine use in the French general population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 60: 523–529, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Magrini N, Vaccheri A, Parma E, D'Alessandro R, Bottoni A, Occhionero M: Use of benzodiazepines in the Italian general population: Prevalence, pattern of use and risk factors for use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 50: 19–25, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Manley HJ, Drayer DK, McClaran M, Bender W, Muther RS: Drug record discrepancies in an outpatient electronic medical record: Frequency, type, and potential impact on patient care at a hemodialysis center. Pharmacotherapy 23: 231–239, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]