Summary

Background and objectives

Collaboration between primary care physicians (PCPs) and nephrologists in the care of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is widely advocated, but physician preferences regarding collaboration are unknown. Physicians' desires to collaborate in the care of a hypothetical patient with CKD, their preferred content of collaboration, and their perceived barriers to collaboration were assessed.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A questionnaire describing the care of a hypothetical patient with progressive CKD was administered to a national sample of U.S. PCPs and nephrologists. Physician characteristics and attitudes associated with desires to collaborate were identified.

Results

Among 124 PCPs and 120 nephrologists, most physicians (85% PCPs versus 94% nephrologists) desired collaboration. Nephrologists were more likely than PCPs to prefer collaboration focus on predialysis/renal replacement therapy preparation and electrolyte management (73% versus 52% and 81% versus 46%, respectively). PCPs were more likely to desire collaboration if the hypothetical patient had diabetes and hypertension (versus hypertension alone), if they believed the care they provide helps slow CKD disease progression, and if they did not perceive health insurance as a barrier to nephrology referral (adjusted percentages [95% confidence interval]: 94% [80 to 98] versus 75% [reference]), 92% [75 to 98] versus 75% [reference], 42% [9 to 85] versus 88% [reference], respectively).

Conclusions

Most PCPs and nephrologists favored collaborative care for a patient with progressive CKD, but their preferred content of collaboration differed. Collaborative models that explicitly include PCPs in the care of patients with CKD may help improve patients' clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Most patients with progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD) or risk factors for CKD progression are cared for by primary care physicians (PCPs) (1). However, evidence suggests PCPs often misjudge the severity of CKD or refer patients to nephrology specialty care so late in their disease progression that interventions to slow CKD progression or prepare patients for renal replacement therapy cannot be implemented in a timely manner (2–4). Lack of timely nephrologist input in the care of patients with progressive CKD has been demonstrated in several studies to be associated with poor clinical outcomes (5–7).

Formal models of PCP-specialist collaboration in the care of patients with progressive CKD, in which PCPs and nephrologists explicitly work together to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of CKD care, have been proposed as an important strategy for achieving the benefits of early specialist input in CKD care while maintaining the continuity of primary care (8,9). Interactive communication between PCPs and specialists in the care of patients with other chronic illnesses (including risk factors for CKD such as diabetes) has been associated with improved clinical outcomes (10). However, evidence suggests that the implementation of collaborative care models for CKD across the United States has been limited, and physicians' optimally preferred models for collaboration have not yet been defined. Furthermore, little is known regarding physician or health care system factors that may pose barriers to physicians' collaboration in the care of patients with CKD.

In a national study, we assessed PCPs' and nephrologists' willingness to collaborate in the care of patients with progressive CKD, their preferred frequency and content of collaboration, and their perceived barriers to collaboration.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

As part of a national study performed (August 2004 to August 2005) to assess physicians' recognition of CKD and their attitudes regarding their care for patients with progressive CKD, we evaluated U.S. PCPs' and nephrologists' preferences regarding PCP-nephrologist collaboration in caring for a patient with progressive CKD using a self-administered questionnaire. We identified a national random stratified sample of 800 PCPs (400 general internists, 400 family physicians) and 400 nephrologists using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile. We attempted to contact physicians up to 11 times. Physicians who were no longer in clinical practice or who were not contactable through follow-up were excluded. Physicians were offered $20 for participation and could complete the questionnaire via mail or the Internet. The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Questionnaire Content

We presented physicians with one of four randomly assigned questionnaires featuring a hypothetical case scenario describing a 50-year-old female patient with hypertension, obesity, and stage 3 CKD progressing to stage 4 CKD being evaluated by a PCP for the first time. The hypothetical scenario was designed to present a patient with clear progression of their CKD from stage 3 (GFR = 30 to 59 ml/min per 1.73 m2) to stage 4 (GFR = 15 to 29 ml/min per 1.73 m2) over a 4-month time period on the basis of an elevated serum creatinine and the presence of gross proteinuria on repeated urine dipstick testing (Appendix A). Scenarios varied randomly by patient race (African American or white) and the presence or absence of diabetes. Questionnaires assessed physicians' abilities to recognize the severity of the patients' CKD, their recommendations for referring the hypothetical patient for nephrology care, and their attitudes regarding engagement in collaborative care between PCPs and nephrologists in their own practices.

Assessment of Physician Characteristics

We assessed physicians' demographics; clinical practice specialty; years in practice; practice type; geographic region; percentage of time spent in clinical, research, or administrative activities; and percentage of time caring for patients with kidney disease. We also assessed physicians' participation in continuous medical education (CME) activities and knowledge of CKD clinical practice guidelines.

Assessment of Physician Recognition of CKD

We assessed physicians' recognition of the hypothetical patient's CKD by asking them, “What is your estimate of Mrs. A's GFR?” Answers could include “I am unsure,” “<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2,” “15 to 29 ml/min per 1.73 m2,” “30 to 59 ml/min per 1.73 m2,” “60 to 89 ml/min per 1.73 m2,” or “90 to 120 ml/min per 1.73 m2.” We also asked physicians, “How would you describe Mrs. A's kidney disease?” Answers could include “normal or no kidney disease,” “mild,” “moderate,” “severe,” or “ESRD.” We considered physicians answering “15 to 29 ml/min per 1.73 m2” or “30 to 59 ml/min per 1.73 m2” or “moderate” or “severe,” respectively, to have correctly estimated the hypothetical patient's GFR.

Assessment of Physician Preferences Regarding Collaborative Care

We assessed physicians' recommendations for referring the hypothetical patient to a nephrologist by asking them, “Based on the information you know about Mrs. A, do you recommend that the primary care physician refer her to a nephrologist at this time?” For physicians recommending referral, we further assessed their desire to collaborate in CKD care by asking them, “Would you advise the primary care physician to send Mrs. A to the nephrologist in order for the nephrologist to take over her care or would you want the primary care physician to continue to manage the care of Mrs. A?” Answers could be “Let the nephrologist take over Mrs. A's care” or “Let the primary care physician continue to care for Mrs. A with a nephrologist's guidance.“ We considered physicians responding that the PCP should continue to care for Mrs. A with a nephrologist's guidance to desire engagement in collaborative care.

For physicians desiring collaboration, we assessed their desired frequency of nephrologists' input by asking, ”How frequently should the primary care physician receive input from the nephrologist?“ Answers included, ”once and then later if needed,“ ”every month,“ ”every 2 to 3 months,“ ”every 4 to 6 months,“ ”every 7 to 9 months,“ ”every 10 to 12 months,“ ”every 1 to 2 years,“ or ”every 2+ years.“ We classified physicians responding ”every month“ or ”every 2 to 3 months“ as desiring more frequent nephrology collaboration. We assessed physicians' preferred content of collaboration by asking, “What types of guidance should the primary care physician seek from the nephrologist?” Physicians could select multiple answers which included, “confirmation of appropriate evaluation to this point,” “additional evaluation and testing for potential causes of kidney disease (e.g., additional laboratory testing, renal biopsy, or other measurements of kidney function),” “nutritional advice,” “advice about medication regimen,” “predialysis/renal replacement therapy preparation,” “electrolyte management,” or “other” (physicians were asked to write in comments).

Assessment of Potential Barriers to Collaborative CKD Care

We assessed physicians' perceived self-efficacy regarding their CKD care by ascertaining the level of their agreement with the statements, “I have enough clinical and administrative resources available to provide all of the appropriate care that my patients with CKD need based on their current conditions” and “I believe that the medical care I implement for patients such as Mrs. A helps to slow progression of CKD and improve outcomes over time.” Possible answers for both questions included “not agree at all,“ ”agree a little,“ ”somewhat agree,“ ”mostly agree,“ or ”completely agree.“

We assessed physicians' perceived system-level barriers to collaborative care by asking them tailored questions (on the basis of their specialty) about the frequency with which they experienced (1) difficulties referring patients to nephrologists (for PCPs), (2) receiving late referrals (for nephrologists), (3) receiving referrals from patients who received inadequate care of CKD by PCPs (for nephrologists), (4) difficulties accommodating additional new patients with CKD in their clinical practices (for nephrologists), and (5) health insurance as a barrier to PCP-nephrologist collaboration (PCPs and nephrologists). We asked PCPs, ”How much of the time do you experience difficulties referring patients like Mrs. A to a nephrologist?“ and “How often does a health insurance plan play a role in whether you choose to refer patients like Mrs. A to a nephrologist?” We asked nephrologists to state the frequency with which “Patients with chronic kidney disease are often referred to me so late in their care that I have little time to intervene with therapies or recommendations that can potentially slow the progression of their CKD” and “Patients who are referred to me have often been prescribed inappropriate medication regimens that do not properly account for their kidney disease.“ We also asked nephrologists to indicate the frequency with which they believed, ”My practice is full, and I have little capacity to accommodate patients who are referred to me for care of their early CKD (before they need dialysis or transplantation).“ We further assessed the frequency with which nephrologists believed ”Health insurance companies often restrict PCPs' abilities to refer patients to me early in their disease when I am more likely to make a difference.“ Answers for all questions regarding potential system-level barriers included, “not at all,” “a little of the time,” “much of the time,” or “most/all of the time.”

Statistical Analyses

We performed bivariate analyses to assess differences in responding and nonresponding physicians and to identify differences in physician' characteristics, attitudes, and preferred types of nephrology guidance in collaboration (χ2 statistic). We performed multivariate logistic regression (stratified according to physician specialty) to identify physician clinical practice characteristics and attitudes as well as hypothetical patient scenario characteristics independently associated with physicians' desires for collaborative care. We also performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis to assess the additional effect of physicians' personal demographic characteristics on their desires to collaborate using a similar multivariable model that included physicians' age, gender, and ethnicity/race in addition to variables included in the main model. Odds ratios were converted to adjusted proportions and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Study Participants

Of 959 eligible physicians, 304 physicians responded (comprised of 178 PCPs [89 general internists and 89 family physicians] and 126 nephrologists). There were no differences between responding and nonresponding physicians with regard to age (mean 46 ± 11 [SD] versus 47 ± 11, respectively; P = 0.156), gender (31% male versus 33% female, respectively; P = 0.468), region (Northeast, 25% versus 23%, Midwest, 23% versus 24%, South, 34% versus 32%, West, 19% versus 21%; P = 0.443), or years in practice (mean 14 ± 12 years versus 14 ± 11 years, respectively; P = 0.905). Nephrologists were more likely than family physicians and general internists to respond (39% versus 28% versus 28%, respectively; P = 0.003).

Of 304 responding physicians, 244 physicians (124 PCPs, 120 nephrologists) who recommended nephrology referral and answered the question regarding collaborative care were included in our analysis. Hypothetical case scenarios were distributed evenly among study physicians. PCPs were more likely than nephrologists to be female, to practice in nonacademic settings, to spend more time in clinical activities, to spend most of their time seeing patients without kidney disease, to not participate regularly in continuous medical education, to be unaware of the existence of referral guidelines, and to incorrectly estimate the GFR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of physicians recommending nephrology referral and answering question regarding collaborative care

| Characteristica | All (n = 244) | PCPs (n = 124) | Nephrologists (n = 120) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician characteristics | ||||

| gender | 0.002 | |||

| female | 72 (30) | 48 (39) | 24 (20) | |

| male | 166 (68) | 75 (60) | 91 (76) | |

| age: median [SD] | 45 [11] | 42 [11] | 47 [11] | NS (0.592) |

| race/ethnicity | NS (0.371) | |||

| non-Hispanic white | 146 (60) | 78 (63) | 68 (57) | |

| other | 92 (38) | 42 (34) | 50 (42) | |

| years in practice | NS (0.059) | |||

| 0 to 10 | 121 (50) | 68 (55) | 53 (44) | |

| >10 | 116 (48) | 55 (45) | 61 (51) | |

| region | 0.034 | |||

| Northeast | 62 (25) | 34 (27) | 28 (23) | |

| Midwest | 52 (21) | 28 (23) | 24 (20) | |

| South | 77 (32) | 29 (23) | 48 (40) | |

| West | 53 (22) | 33 (27) | 20 (17) | |

| practice settingb | ||||

| solo private | 29 (12) | 18 (15) | 11 (9) | NS (0.434) |

| group private | 120 (49) | 56 (45) | 64 (53) | NS (0.125) |

| health maintenance organization | 11 (5) | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | NS (0.967) |

| university or medical school | 60 (25) | 21 (17) | 39 (33) | 0.014 |

| community hospital | 59 (24) | 29 (24) | 30 (25) | NS (0.706) |

| government facility | 21 (9) | 15 (12) | 6 (5) | NS (0.141) |

| percentage of time spent in: mean [SD] | ||||

| clinical activities | 82 [24] | 88 [20] | 76 [26] | 0.002 |

| research activities | 11 [20] | 6 [17] | 15 [22] | 0.013 |

| administrative activities | 13 [17] | 12 [16] | 15 [18] | 0.005 |

| percentage of time spent seeing: mean [SD] | ||||

| patients with kidney disease | 48 [40] | 14 [12] | 85 [21] | <0.001 |

| patients with other diseases | 54 [38] | 84 [16] | 16 [18] | <0.001 |

| regular participation in CME | <0.001 | |||

| no | 44 (18) | 35 (28) | 9 (8) | |

| yes | 200 (82) | 89 (72) | 111 (92) | |

| knowledge of referral guidelines | <0.001 | |||

| no/unsure | 103 (42) | 79 (64) | 24 (20) | |

| yes | 139 (57) | 44 (35) | 95 (79) | |

| correct estimation of GFRc | 0.001 | |||

| no | 23 (9) | 20 (16) | 3 (2) | |

| yes | 220 (90) | 103 (83) | 117 (98) | |

| Patient scenario characteristics | ||||

| patient race | NS (0.528) | |||

| white | 127 (52) | 57 (46) | 60 (50) | |

| black | 117 (48) | 67 (54) | 60 (50) | |

| patient comorbidity | NS (0.163) | |||

| hypertension only | 115 (47) | 53 (43) | 62 (52) | |

| diabetes and hypertension | 129 (53) | 71 (57) | 58 (48) |

Values expressed as number (percent) or mean [SD]. Percentages may not equal 100% because of missing values. CME, continuing medical education.

Of 244 physicians recommending nephrology referral and answering question regarding collaborative care.

Answers were not mutually exclusive.

Among PCPs, 87% of general internists and 80% of family physicians correctly estimated the GFR (P = 0.273).

Physicians' Preferences Regarding Collaborative Care

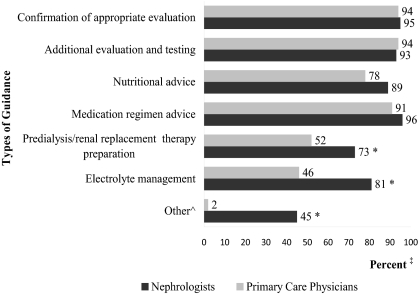

A significant majority of all physicians (n = 218 [89%]; 105 PCPs, 113 nephrologists), but statistically significantly more nephrologists versus PCPs (94% versus 85%, respectively; P = 0.016) reported they desired collaborative care. Among these physicians, less than one third (n = 63, 29%) reported they desired more frequent (at least every 2 to 3 months) collaboration. The most frequently desired types of input from nephrologists in collaborative care were (1) confirmation of PCPs' appropriate clinical evaluation, (2) guidance regarding additional evaluation and testing, (3) medication regimen advice, and (4) nutritional advice. PCPs were statistically significantly less likely than nephrologists to seek guidance regarding predialysis/renal replacement therapy preparation, electrolyte management, or other CKD-related illnesses such as metabolic bone disease and anemia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferences regarding type of nephrology guidance that should be provided for hypothetical patient with CKD. *P < 0.05. ‡Percentage of physicians recommending referral and desiring collaborative care (105 PCPs, 113 nephrologists) who desire a specific type of nephrology guidance. “^Other” includes metabolic bone disease (0% of PCPs, 15% of nephrologists), anemia (1% of PCPs, 14% of nephrologists), hypertension (1% of PCPs, 4% of nephrologists), pretransplant education (0% of PCPs, 2% of nephrologists), lipids (0% of PCPs, 6% of nephrologists), CKD/ESRD education (1% of PCPs, 3% of nephrologists), and acid-base (0% of PCPs, 4% of nephrologists).

Potential Barriers to Collaborative Care

Nephrologists were more likely than PCPs to report they had sufficient ancillary support for the care of their patients with CKD and that they felt that the medical care they provide was helpful in slowing CKD disease progression. Nephrologists were also more likely than PCPs to perceive insurance as a barrier to nephrology referral. More than half of nephrologists felt patients were referred too late, and nearly one third felt patients seen in consultation were on inappropriate medications. Most PCPs did not report difficulty in referring patients to nephrology (Table 2).

Table 2.

Physician attitudes regarding the collaborative care of a hypothetical patient with CKD

| Characteristica/Physician Attitudes | All (n = 244) | PCPs (n = 124) | Nephrologists (n = 120) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived ancillary support | <0.001 | |||

| lacking | 102 (42) | 68 (55) | 34 (28) | |

| sufficient | 139 (57) | 55 (44) | 84 (70) | |

| Medical care I provide slows diseaseb | <0.001 | |||

| no | 34 (14) | 28 (23) | 6 (5) | |

| yes | 207 (85) | 94 (76) | 113 (94) | |

| Insurance plays role in referralc | 0.014 | |||

| never/rarely | 205 (84) | 112 (90) | 93 (78) | |

| often/always | 33 (14) | 9 (7) | 24 (20) | |

| Difficulty referring to nephrologyd | NA | |||

| never/rarely | – | 106 (85) | ||

| often/always | 17 (14) | – | ||

| Patients referred too latee | NA | |||

| disagree | – | – | 55 (46) | |

| agree | 63 (53) | |||

| Inappropriate medicationsf | NA | |||

| disagree | – | – | 82 (68) | |

| agree | 35 (29) | |||

| Practice too full to accommodateg | NA | |||

| disagree | – | – | 105 (88) | |

| agree | 11 (9) |

Values expressed as number (percent). Percentages may not equal 100% because of missing values.

Of 244 physicians recommending nephrology referral and answering question regarding collaborative care.

Physicians were asked if they believed the medical care they implemented for patients such as in the hypothetical scenario helps to slow progression of kidney disease and improve outcomes.

PCPs were asked how often insurance plays a role in their decision to refer to nephrology. Nephrologists were asked if they felt health insurance restricts PCPs' abilities to refer early.

PCPs were asked how often they had difficulty referring to nephrology.

Nephrologists were asked if they felt patients were referred to nephrology late in their care, without time to potentially slow progression of their CKD.

Nephrologists were asked if they felt patients referred to them have been prescribed inappropriate medication regimens.

Nephrologists were asked if they felt they had little capacity to accommodate early CKD patients.

Factors Associated with Physicians' Preferences Regarding Participation in Collaborative Care

After adjustment, PCPs were more likely to desire collaborative care if the hypothetical patient in their scenario had diabetes and hypertension and if they believed the care they provided was helpful in slowing disease progression. PCPs were less likely to desire collaborative care if they felt insurance plays a role in their ability to refer to nephrology (Table 3). A post hoc sensitivity analysis additionally adjusting for physician's personal demographic characteristics revealed similar findings. However, non-Hispanic white PCPs were statistically significantly more likely to be willing to collaborate compared with their ethnic/racial minority counterparts (adjusted proportion 92% [75 to 98] versus 74%, P = 0.042). There were no differences in nephrologists' willingness to collaborate according to their personal demographic characteristics.

Table 3.

Physician and hypothetical patient scenario characteristics, and physician attitudes associated with desire for collaborative care

| Characteristic | Percentages Desiring Collaborative Care |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCPs |

Nephrologists |

|||||

| Unadjusted Proportion | Adjusted Proportion (95% confidence interval) | P | Unadjusted Proportion | Adjusted Proportion (95% confidence interval) | P | |

| Physician characteristics | ||||||

| years in practice | 0.423 | 0.656 | ||||

| 0 to 10 | 82 | 82 (reference) | 91 | 91 (reference) | ||

| >10 | 89 | 89 (68 to 97) | 97 | 94 (60 to 99) | ||

| region | ||||||

| Northeast | 85 | 85 (reference) | 0.838 | 96 | 96 (reference) | – |

| Midwest | 89 | 83 (42 to 97) | 0.294 | 92 | 85 (11 to 100) | 0.424 |

| South | 79 | 69 (28 to 93) | 0.760 | 92 | 92 (32 to 100) | 0.603 |

| West | 85 | 88 (56 to 98) | 100 | a | – | |

| practice setting | 0.215 | 0.286 | ||||

| nonacademic | 83 | 83 (reference) | 93 | 93 (reference) | ||

| academic center | 95 | 95 (69 to 99) | 95 | 98 (80 to 100) | ||

| regular participation in CME | 0.088 | 0.770 | ||||

| no | 77 | 77 (reference) | 78 | 78 (reference) | ||

| yes | 88 | 92 (74 to 98) | 96 | 88 (5 to 100) | ||

| knowledge of referral guidelines | 0.483 | 0.051 | ||||

| no/unsure | 82 | 82 (reference) | 79 | 79 (reference) | ||

| yes | 91 | 88 (65 to 97) | 98 | 98 (79 to 100) | ||

| correct estimation of GFR | 0.496 | – | ||||

| no | 90 | 90 (reference) | 100 | 100 (reference) | ||

| yes | 84 | 80 (29 to 98) | 94 | b | ||

| Patient scenario characteristics | ||||||

| patient scenario race | 0.865 | 0.756 | ||||

| white | 88 | 88 (reference) | 95 | 95 (reference) | ||

| black | 82 | 89 (69 to 97) | 93 | 96 (74 to 100) | ||

| patient scenario comorbidity | 0.021 | 0.697 | ||||

| hypertension only | 75 | 75 (reference) | 95 | 95 (reference) | ||

| diabetes and hypertension | 92 | 94 (80 to 98) | 93 | 93 (55 to 99) | ||

| Physician attitudes | ||||||

| perceived ancillary support | 0.621 | 0.328 | ||||

| lacking | 85 | 85 (reference) | 97 | 97 (reference) | ||

| sufficient | 85 | 80 (48 to 95) | 93 | 83 (10 to 100) | ||

| medical care I provide slows diseasec | 0.049 | – | ||||

| no | 75 | 75 (reference) | 100 | 100 (reference) | ||

| yes | 88 | 92 (75 to 98) | 94 | d | ||

| insurance plays role in referrale | 0.033 | – | ||||

| never/rarely | 88 | 88 (reference) | 94 | 94 (reference) | ||

| often/always | 56 | 42 (9 to 85) | 96 | e | ||

| difficulty referring to nephrologyf | 0.246 | n/a | ||||

| never/rarely | 84 | 84 (reference) | – | – | ||

| often/always | 94 | 92 (75 to 98) | ||||

| patients referred too lateg | 0.798 | |||||

| disagree | – | – | NA | 93 | 93 (reference) | |

| agree | 95 | 94 (66 to 99) | ||||

| inappropriate medsh | 0.895 | |||||

| disagree | – | – | NA | 94 | 94 (reference) | |

| agree | 94 | 95 (47 to 100) | ||||

| practice too full to accommodatei | 0.697 | |||||

| disagree | – | – | NA | 95 | 95 (reference) | |

| agree | 91 | 75 (2 to 100) | ||||

All nephrologists from the West desired collaborative care.

All nephrologists who correctly identified the GFR desired collaborative care.

Physicians were asked if they believed the medical care they implemented for patients such as in the hypothetical scenario helps to slow progression of kidney disease and improve outcomes.

All nephrologists who felt their care was helpful desired collaborative care.

PCPs were asked how often insurance plays a role in their decision to refer to nephrology. Nephrologists were asked if they felt health insurance restricts PCPs abilities to refer early. All nephrologists who felt insurance played a role desired collaborative care.

PCPs were asked how often they had difficulty referring to nephrology.

Nephrologists were asked if they felt patients were referred to nephrology late in their care, without time to potentially slow progression of their CKD.

Nephrologists were asked if they felt patients referred to them have been prescribed inappropriate medication regimens.

Nephrologists were asked if they felt they had little capacity to accommodate early CKD patients.

Discussion

In this national study, most PCPs and nephrologists reported they prefer to collaborate in the care of patients with progressive CKD, with PCPs maintaining a primary role in patients' care. However, nephrologists were more likely than PCPs to desire that collaboration address predialysis/renal replacement therapy preparation, electrolyte management, and other aspects of care (including anemia management). One half of nephrologists believed patients were referred late. Consistent with this were PCPs perceived barriers to collaboration, including deficiencies in ancillary support to care for patients with CKD. PCPs provided with a hypothetical patient scenario featuring a patient with hypertension and diabetes, with greater perceived self-efficacy regarding the ability of their care to slow CKD progression, or who did not perceive insurance as a barrier to their nephrology referrals were statistically significantly more likely than their counterparts to desire collaboration.

To our knowledge, this is the first national study to assess physicians' preferences regarding the occurrence and content of PCPs' and nephrologists' collaboration in CKD care. Previous studies of PCP-specialist collaboration in the care of other illnesses such as diabetes and mental illnesses revealed that good patient-specialist interaction, insurance coverage, and specialist efforts to return the mutual patient to primary care were of major importance to PCPs (11) and that effective PCP-specialist communication was associated with patients' improved clinical outcomes (10). Prior studies assessing the potential benefit of multidisciplinary care (12–14) for patients with CKD did not specifically address the ongoing role of PCPs in care, nor did they specify physicians' desired content of collaboration. Although collaborative models of care are being encouraged within the nephrology community, little information has been available to inform their development (8,15–17). Our findings provide evidence of consensus among PCPs and nephrologists regarding features of collaboration viewed as most beneficial to patients.

Physicians' support for PCPs' continued primary role in patients' CKD care is consistent with findings in other clinical areas suggesting multidisciplinary collaborations should explicitly include PCPs in the process of care (18). In studies examining primary care-specialist collaboration in the care of patients with other chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease and gastrointestinal disorders, lapses in PCP-specialist communication have been linked to inefficiencies in care such as repeat referrals by PCPs and specialists' inability to address the reason for consultation (19–21). Few physicians believed nephrologists should have more frequent input into patients' care, suggesting periodic comprehensive collaboration would be viewed as more useful than parallel (and possibly duplicative) care by PCPs and nephrologists. PCPs' and nephrologists' similar desires for nephrologist input regarding identifying the etiology and severity of CKD, as well as the improved management of risk factors for CKD progression, suggest these factors might be addressed with highest priority in collaborative care. Nephrologists' additional desires to address factors not as frequently identified as high priority among PCPs (e.g., anemia and electrolyte management) underscore the potential for collaboration to enhance clinical care.

Greater willingness to collaborate among PCPs presented with hypothetical patients with diabetes and hypertension suggests PCPs might more readily recognize the benefits of collaboration when they perceive their patients are at greater risk of CKD progression. Similarly, greater desire for collaboration among PCPs reporting greater perceived self-efficacy regarding their CKD care suggests efforts to educate PCPs regarding the benefits of appropriate therapy on CKD progression could enhance their desires to collaborate. Our analysis did not elucidate potential mechanisms through which PCPs' ethnicity/race might contribute to their willingness to collaborate. Prior studies have shown that ethnic/racial minority physicians are more likely to care for patients of low socioeconomic status (22,23) who may have difficulties obtaining medications or adhering to therapy. Such difficulties in care could affect minority PCPs' confidence in the potential success of collaborative subspecialty care relationships. The provision of more comprehensive early education of medical students and residents regarding the need to address patients' CKD-related comorbid conditions (including anemia and metabolic derangements), particularly among ethnic/racial minority patients of low socioeconomic status who are at greater risk of CKD progression compared with the general public, could help improve PCPs' confidence regarding the yield of collaborative care.

PCPs' and nephrologists' differing views regarding health insurance as a barrier to referral may reflect their perceptions of payment structures in place at the time of our study that did not yet embrace collaborative care models. Recent enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) could influence physicians' future views of collaborative care for CKD in at least two ways. First, the potential burden on PCPs to care for the projected significant increase in the number of persons seeking primary care services—many of whom will have diabetes, hypertension, and CKD—as a result of improved health insurance coverage could increase PCPs' willingness to seek specialist co-management for patients with chronic illnesses such as CKD (24). Second, the PPACA also implements payment structures that encourage coordinated care models (such the Patient-Centered Medical Home [25]) for patients with chronic illnesses (26).

Our study has limitations. First, use of a hypothetical patient scenario allowed for evaluation of practice patterns under uniform conditions, but some laboratory values assigned to the hypothetical patient may not have reflected common scenarios encountered among patients with CKD in real clinical practice (e.g., chronic anemia). Second, we did not assess physicians' attitudes regarding some important aspects of collaboration, including the management and/or prevention of common risks among patients with CKD (e.g., cardiovascular disease or prevention of acute kidney injury), the quality of information exchange between PCPs and nephrologists, or the role of other types of health care providers (e.g., nurses) in collaboration (10,12–14). We also did not assess some physician characteristics (e.g., board certification, salary status) that could influence physicians' willingness to collaborate. Last, despite identifying a national sample of physicians, our response rate was limited. It is possible that physicians participating in our study were more interested than nonparticipants in CKD care and could have different views on collaboration. Furthermore, providers were not distributed evenly across the United States, and regional variation in clinical practice could have influenced our findings.

In summary, we found that most U.S. physicians favored a collaborative approach to the care of a patient with progressive CKD and preferred that PCPs play a significant ongoing role in care. Collaborative models that explicitly include PCPs in CKD care and that specify the roles of PCPs and nephrologists in addressing the needs of patients may improve the quality of patients' care and clinical outcomes.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Diamantidis received support from grant KL2RR025006 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Powe received support from grant K24DK02643 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Dr. Greer received support from a Research Supplement to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research, grant RO1DK079682, from NIDDK. Dr. Boulware received support from the Robert Wood Johnson Harold Amos Faculty Development Program and grant K23DK070757 from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities and NIDDK.

Appendix A.

| Reason for visit | ||

| Past medical history | 10-year duration of hypertension, obesity, ±diabetes mellitus. Patient is a nonsmoker. | |

| Review of systems | Unremarkable—no neurological or vascular symptoms | |

| Medications | Daily diuretic and acetaminophen. Patients with diabetes were also taking an ARB and oral hypoglycemic agent. | |

| Physical examination | Blood pressure 125/80, weight 154 lb, height 5 ft, 2 in. Remainder of exam was normal. | |

| Laboratory results | 4 months ago | 1 week ago |

| serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.8a (white) | 2.0b (white) |

| 2.1a (African American) | 2.3b (African American) | |

| comprehensive metabolic panelc | Normal | Normal |

| complete blood countd | Normal | Normal |

| hemoglobin A1c | 6.3 | 6.8 |

| urine protein (gross dipstick) | 1+ | 1+ |

Participants were randomly assigned one of four possible scenarios that varied on patient race (African American or white) and the presence or absence of diabetes.

Estimated GFR for the white and African-American patient was 32 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (using the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation) (28).

Estimated GFR was 28 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and 29 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for the white and African-American patient, respectively (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation) (28).

Comprehensive metabolic panel includes sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, glucose, calcium, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, albumin, total protein, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and bilirubin.

Complete blood count includes hemoglobin, hematocrit, white blood cell count, and platelets.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. U.S. Renal Data System: USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boulware LE, Troll MU, Jaar BG, Myers DI, Powe NR: Identification and referral of patients with progressive CKD: A national study. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 192–204, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Owen WF, Jr, Avorn J: Determinants of delayed nephrologist referral in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 1178–1184, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Navaneethan SD, Aloudat S, Singh S: A systematic review of patient and health system characteristics associated with late referral in chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 9: 3, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kinchen KS, Sadler J, Fink N, Brookmeyer R, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Powe NR: The timing of specialist evaluation in chronic kidney disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med 137: 479–486, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakamura S, Nakata H, Yoshihara F, Kamide K, Horio T, Nakahama H, Kawano Y: Effect of early nephrology referral on the initiation of hemodialysis and survival in patients with chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular diseases. Circ J 71: 511–516, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kazmi WH, Obrador GT, Khan SS, Pereira BJ, Kausz AT: Late nephrology referral and mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease: A propensity score analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1808–1814, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Implementing a disease management program for chronic kidney disease. Manag Care 12[Suppl]: S1–S29, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Narva AS: Optimal preparation for ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4[Suppl 1]: S110–S113, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Foy R, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, Suttorp M, Seelig M, Shanman R, Shekelle PG: Meta-analysis: Effect of interactive communication between collaborating primary care physicians and specialists. Ann Intern Med 152: 247–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kinchen KS, Cooper LA, Levine D, Wang NY, Powe NR: Referral of patients to specialists: Factors affecting choice of specialist by primary care physicians. Ann Fam Med 2: 245–252, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wei SY, Chang YY, Mau LW, Lin MY, Chiu HC, Tsai JC, Huang CJ, Chen HC, Hwang SJ: Chronic kidney disease care program improves quality of pre-end-stage renal disease care and reduces medical costs. Nephrology (Carlton) 15: 108–115, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Curtis BM, Ravani P, Malberti F, Kennett F, Taylor PA, Djurdjev O, Levin A: The short- and long-term impact of multi-disciplinary clinics in addition to standard nephrology care on patient outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 147–154, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Zhang J, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Walsh M, Culleton BF: Association between multidisciplinary care and survival for elderly patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 993–999, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levin A, Stevens LA: Executing change in the management of chronic kidney disease: perspectives on guidelines and practice. Med Clin North Am 89: 701–709, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. St Peter WL, Schoolwerth AC, McGowan T, McClellan WM: Chronic kidney disease: Issues and establishing programs and clinics for improved patient outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 903–924, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beaulieu M, Levin A: Analysis of multidisciplinary care models and interface with primary care in management of chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol 29: 467–474, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Linzer M, Myerburg RJ, Kutner JS, Wilcox CM, Oddone E, DeHoratius RJ, Naccarelli GV: Exploring the generalist-subspecialist interface in internal medicine. Am J Med 119: 528–537, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen AH, Yee HF, Jr: Improving the primary care-specialty care interface: Getting from here to there. Arch Intern Med 169: 1024–1026, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gandhi TK, Sittig DF, Franklin M, Sussman AJ, Fairchild DG, Bates DW: Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med 15: 626–631, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McPhee SJ, Lo B, Saika GY, Meltzer R: How good is communication between primary care physicians and subspecialty consultants? Arch Intern Med 144: 1265–1268, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, Vranizan K, Lurie N, Keane D, Bindman AB: The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med 334: 1305–1310, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moy E, Bartman BA: Physician race and care of minority and medically indigent patients. JAMA 273: 1515–1520, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Congressional Budget Office: Preliminary estimate of the direct spending and revenue effects of an amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 4872, the Reconciliation Act of 2010, March 2010. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11355/hr4872.pdf Accessed August 16, 2010

- 25. American College of Physicians: The advanced medical home: A patient-centered, physician-guided model of health care. Available at: http://www.acponline.org/hpp/adv_med.pdf Accessed August 16, 2010

- 26. Kirschner N, Barr MS: Specialists/subspecialists and the patient-centered medical home. Chest 137: 200–204, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Charles RF, Powe NR, Jaar BG, Troll MU, Parekh RS, Boulware LE: Clinical testing patterns and cost implications of variation in the evaluation of CKD among U.S. physicians. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 227–237, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D: A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]