Summary

Background and objectives

Renal disease disproportionately affects African-American patients. Trust has been implicated as an important factor in patient outcomes. Higher levels of trust and better interpersonal care have been reported when race of patient and physician are concordant. The purpose of this analysis was to examine trends in the racial background of U.S. medical school graduates, internal medicine residents, nephrology fellows, and patients with ESRD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Data for medical school graduates were obtained from the Association of American Medical Colleges and data for internal medicine and nephrology trainees from GME Track. ESRD data were obtained from U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS) annual reports.

Results

A significant disparity continues to exist between the proportional race makeup of African-American nephrology fellows (3.8%) and ESRD patients (32%). The low numbers of African-American nephrology fellows, and consequently new nephrologists, in light of the increase in ESRD patients has important implications for patient-centered nephrology care.

Conclusions

Efforts are needed to increase minority recruitment into nephrology training programs, to more closely balance the racial background of trainees and patients in hopes of fostering improved trust between ESRD caregivers and patients, increasing access to care, alleviating ESRD health care disparities, and improving patient care.

Introduction

Renal disease disproportionately affects African-American patients in the United States. African Americans make up approximately 13% of the U.S. population, but comprise approximately 32% of the U.S. ESRD population (1). A review by Powe highlights the continued disproportionate effects of kidney disease on African Americans and its associated challenges (2). One of the primary goals of the Healthy People 2010 initiative is to eliminate health care disparities; chronic kidney disease (CKD) was designated as one of the focus areas (3). It has been strongly hypothesized that more concordance of patient and physician race or ethnic background may help eliminate health disparities, and increasing health care provider ethnic diversity has been a suggested target strategy (3).

Trust, a critical factor in the therapeutic relationship between patients and their practitioners (4), is associated with willingness to seek care and adhere to recommended treatments. Increased trust occurs when patients and practitioners share similar racial backgrounds, a situation that leads to better communication, increased patient satisfaction, and a greater sense of participation in the visit (4–6). In addition, African-American physicians have a greater tendency to serve African-American patients, thereby becoming a source of care for this underserved population, which increases access to care and potentially improves outcomes (7).

A goal for many years has been to increase the number of African-American fellows in nephrology programs in an effort to improve health care delivery to an important population with CKD (5,8). The purpose of this analysis was to examine the trends in the racial backgrounds of ESRD patients and nephrology fellows and discuss the implications of these trends on ESRD care.

Materials and Methods

Demographic data regarding internal medicine residents and nephrology fellowship trainees were obtained from the National Graduate Medical Education (NGME) Census obtained through GME Track. This is an internet-based system administered jointly by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the American Medical Association (AMA). Information from the GME Track survey is published in the annual medical education issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (9–19). The most recent data are for the 2008 to 2009 academic year and included 141 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-approved adult nephrology fellowship programs (19). The data for residents and fellows are for the total number in all years of training.

Demographic data regarding medical school graduates were obtained from the AAMC Data Warehouse available online (http://www.aamc.org/data/facts/enrollmentgraduate/start.htm). The medical student data are for graduates in a given year.

Demographic data regarding ESRD patients were obtained from the annual data report of ESRD and CKD published by the U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS) (1). The USRDS is a national data system funded directly by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) in conjunction with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that collects, analyzes, and distributes information about ESRD in the United States.

Results

The number and percent of African-American medical school graduates, internal medicine residents, nephrology fellows, and ESRD patients is displayed in Table 1. Between 2002 and 2009, the number of African-American medical school graduates remained stable with a range of 1012 to 1123 graduates (6.5% to 7.1%).

Table 1.

Number of African-American medical school graduates, internal medicine residents, nephrology fellows, and ESRD patients with corresponding percent of total

| Year | Medical School Graduates (%) | Internal Medicine Residents (%) | Nephrology Fellows (%) | ESRD Patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 1076 (6.5) | NA | NA | NA |

| 2008 | 1112 (6.9) | 1219 (5.5) | 31 (3.8) | NA |

| 2007 | 1086 (6.7) | 1182 (5.4) | 49 (6.1) | 166,962 (31.7) |

| 2006 | 1123 (7.1) | 1215 (5.5) | 51 (6.4) | 160,497 (31.6) |

| 2005 | 1044 (6.6) | 1055 (4.8) | 45 (5.5) | 154,191 (31.7) |

| 2004 | 1032 (6.5) | 1066 (5.0) | 38 (4.9) | 148,539 (31.8) |

| 2003 | 1012 (6.5) | 1097 (5.1) | 36 (4.7) | 143,754 (32.0) |

| 2002 | 1087 (6.9) | 1137 (5.4) | 29 (4.1) | 138,075 (32.1) |

| 2001 | NA | 1221 (5.8) | 35 (5.4) | 132,200 (32.1) |

| 2000 | NA | 1336 (6.3) | 29 (4.6) | 126,717 (32.3) |

| 1999 | NA | 1178 (5.5) | 26 (3.8) | 120,868 (32.6) |

NA, not available.

Between 1999 and 2008, there were approximately 20,000 to 22,000 residents each year in ACGME-accredited internal medicine training programs. Of these internal medicine residents, African Americans comprised 4.8% to 6.3% during that time, with numbers of African-American trainees ranging between 1055 and 1336. The 2000 to 2001 academic year marks the peak of the number of African-American internal medicine trainees (6.3% and 1336 total) and more recently, the percentage of African-American internal medicine residents has reached a plateau at approximately 5.5%.

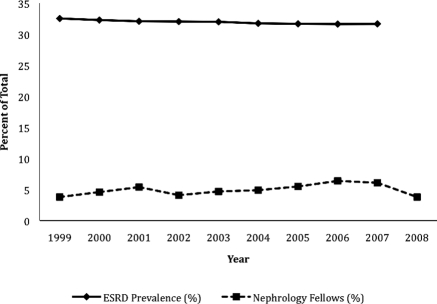

Between 1999 and 2008, the number of nephrology fellows nationwide increased 19.8%, from 678 to 812 (data not shown). The number of African-American nephrology fellows during that time frame ranged from 26 to 51, varying from 3.8% to 6.4% of all nephrology trainees (Figure 1). There was nearly a doubling in the number of African-American nephrology fellows between 1999 and 2006. However, the percentage of African-American nephrology fellows decreased to 6.1% in 2007 and 3.8% in 2008.

Figure 1.

Point-prevalence percentage of African-American ESRD patients and percentage of African-American nephrology fellows in a given year.

The point-prevalent counts of African Americans with ESRD have steadily increased between 1999 and 2007 with an overall increase of 44,402 patients. The percentage of ESRD patients that are African American has remained approximately 32% as the number of ESRD patients in other racial groups has risen. These data highlight the continued disparity between African-American patients with ESRD and the number of African-American fellows training to become nephrologists (Figure 1).

Discussion

Disparities continue to exist between the racial background of ESRD patients and that of the physicians who care for them. African Americans account for 13% of the U.S. population yet only comprise 6.5% to 7.1% of U.S. medical school graduates, 5.5% of internal medicine residents, and a mere 3.8% of all nephrology fellows (31 trainees). This change in nephrology fellows is not due to a reduction in the number of nephrology trainees because the overall number has increased 19.8% nationwide between 1999 and 2008. Furthermore, there has been a 4.5% decrease in African-American nephrology faculty between 1998 and 2008 with only 28 (3.3%) academic nephrology faculty being African American (20). There are no available data on the racial makeup of nephrologists in private practice.

It has been well established that the growing burden of renal disease disproportionately affects African Americans in the United States (2,21–25). Mechanisms accounting for African Americans' predilection toward ESRD are not clearly understood. Socioeconomic status, including poverty and lower education, has been implicated. Personal health behaviors and the presence of other comorbidities may also contribute to the disparities regarding kidney disease. Clinical factors such as diabetes and hypertension have been found to account for the largest degree of excess risk from modifiable risk factors. Familial clustering of renal disease has been reported, and with the identification of several candidate genes such as MYH9, the role of genetic factors is increasingly being recognized (26,27). Access to medical care is another key factor. There is evidence that African Americans are evaluated later in the disease course and tend to have more rapid progression of their kidney disease (23).

Trust can play an integral role in patient-physician relationships. A patient's trust in his or her physician may help improve clinical outcomes (6,28–32). Distrust in health care is often cited as a major contributing factor in racial disparities because it may interfere with access to medical care and adherence to medical advice given by health care providers (30). This distrust can translate to decreased access to and knowledge of medical treatments as well as lack of willingness to adhere to medical advice and to participate in clinical trials and studies. In addition, distrust in one's health care provider is associated with decreased use of recommended preventive services (29,31,32). Perceived discrimination may be associated with stress and maladaptive health behaviors that could pose barriers to success in delivering care and adherence to recommendations (33–35). The degree to which racial discordance plays a role in the care relationship in nephrology is uncertain. Furthermore, there is no evidence that trust cannot develop between racially discordant patients and providers.

Low numbers of African-American nephrology trainees and consequently low numbers of new African-American nephrologists, both academic and nonacademic, in the midst of increasing numbers of African-American ESRD patients has important implications for ESRD care. Specific data regarding nephrologist-patient relationships and quality of care when race is concordant and trends in African-American nephrologists' practice locations are lacking and are potential subjects for future study. Nevertheless, with the most recent data showing a decrease in the number and percentage of African-American nephrology fellows in the last year, the importance of increasing minority recruitment in nephrology is magnified. However, increasing minority nephrologists will not alone solve health care disparities in ESRD. It has been recommended that movement toward culturally competent care systems be implemented nationally to address racial disparities in health care (36). In the meantime, health care providers and institutions need to strive for accessible and quality care according to the Healthy People 2010 charge (3).

Although methods for increasing cultural competence, improving equality of health care, and expanding access to care are being explored nationally, simultaneous efforts are needed to increase minority recruitment to more closely balance the race of trainees and patients (2). Such initiatives could be associated with improved patient outcomes in the ESRD program but may also have an effect on other areas of health care. Multiple strategies are needed to increase minority recruitment to the health care workforce. As suggested by the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce (37), the culture of health professions schools must change with new and nontraditional paths to the health professions explored. The report stressed that commitments to workforce diversity must be at the highest levels.

A greater emphasis on medical school recruitment efforts must provide the foundation for diversifying the physician workforce. Because of continued disparity in primary and secondary education among minorities, there have been initiatives to strengthen the educational pipeline by partnering academic medical centers with local school districts and colleges (38). Patterson and colleagues emphasize the great necessity for health profession-public school partnerships to increase minority access to health careers and provide a framework for the development and sustainment of such collaborations (39). Continued and, in some cases, expansion of funding of such initiatives to strengthen the educational pipeline are vital components in the effort to increase minority physicians. Partnering with minority medical student organizations such as the Student National Medical Association (SNMA) may also prove beneficial (40). Working with SNMA on local and national levels would promote earlier minority exposure to the field and provide a gateway to valuable mentoring relationships.

Other valuable resources are diversity councils. Nephrology fellowship program directors should work closely with already existing diversity councils at their institutions or work toward the development of diversity councils to identify specific challenges to minority medical student, resident, and fellow recruitment and minority faculty development (41). It is critical that minorities are recruited to stay in academics and are represented on medical school faculties and key institutional committees particularly in specialties such as nephrology in which racial disparities exist between patients and physicians. Nephrology fellows should be encouraged and supported to enter academics as clinicians, educators, or researchers.

In conclusion, continued racial disparities in CKD exist with a disproportionate number of African-American patients having kidney disease. Given the integral role of patient and physician race concordance in the therapeutic relationship, efforts to increase the number of African-American nephrology trainees may help to optimize patient care and improve outcomes.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Part of this material was presented at the 2008 annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology; November 4 through November 9, 2008; Philadelphia, PA. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, the NIDDK, or the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. U.S. Renal Data System: USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Powe NR: To have and have not: Health and health care disparities in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 64: 763–772, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Healthy People 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2010.htm Accessed March 22, 2010

- 4. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, Ford DE: Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA 282: 583–589, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pogue VA, Norris KC, Dillard MG: Kidney disease physician workforce: Where is the emerging pipeline? J Natl Med Assoc 94: 39S–44S, 2002 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR: Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med 139: 907–915, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, Vranizan K, Lurie N, Keane D, Bindman AB: The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med 334: 1305–1310, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosenberg ME: Adult nephrology fellowship training in the United States: trends and issues. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1027–1033, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Appendix: II. Graduate Medical Education. JAMA 284: 1159–1172, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Graduate medical education. JAMA 286: 1095–1107, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Graduate medical education. JAMA 288: 1151–1164, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Career plans. In: Internal Medicine In-Training Examination, Steering Committee Meeting, Philadelphia, PA, American College of Physicians, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graduate medial education. JAMA 290: 1234–1238, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Graduate medical education. JAMA 292: 1099–1113, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Graduate medical education. JAMA 294: 1129–1143, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graduate medical education. JAMA 296: 1154–1169, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graduate medical education. JAMA 298: 1081–1096, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Graduate medical education. JAMA 300: 1228–1243, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graduate medical education. JAMA 302: 1357–1372, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kohan DE, Baird BC: The changing phenotype of academic nephrology—A future at risk? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 2051–2058, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choi AI, Rodriguez RA, Bacchetti P, Bertenthal D, Hernandez GT, O'Hare AM: White/black racial differences in risk of end-stage renal disease and death. Am J Med 122: 672–678, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gao SW, Oliver DK, Das N, Hurst FP, Lentine KL, Agodoa LY, Sawyers ES, Abbott KC: Assessment of racial disparities in chronic kidney disease stage 3 and 4 care in the Department of Defense health system. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 442–449, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hsu CY, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG: Racial differences in the progression from chronic renal insufficiency to end-stage renal disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2902–2907, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishani A, Grandits GA, Grimm RH, Svendsen KH, Collins AJ, Prineas RJ, Neaton JD: Association of single measurements of dipstick proteinuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and hematocrit with 25-year incidence of end-stage renal disease in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1444–1452, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Norris KC, Agodoa LY: Unraveling the racial disparities associated with kidney disease. Kidney Int 68: 914–924, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Freedman BI, Sedor JR: Hypertension-associated kidney disease: Perhaps no more. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2047–2051, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kao WH, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, Reich D, Berthier-Schaad Y, Li M, Coresh J, Patterson N, Tandon A, Powe NR, Fink NE, Sadler JH, Weir MR, Abboud HE, Adler SG, Divers J, Iyengar SK, Freedman BI, Kimmel PL, Knowler WC, Kohn OF, Kramp K, Leehey DJ, Nicholas SB, Pahl MV, Schelling JR, Sedor JR, Thornley-Brown D, Winkler CA, Smith MW, Parekh RS: MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nat Genet 40: 1185–1192, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR: Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep 118: 358–365, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O'Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J: The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med 38: 777–785, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Halbert CH, Armstrong K, Gandy OH, Jr, Shaker L: Racial differences in trust in health care providers. Arch Intern Med 166: 896–901, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carpenter WR, Godley PA, Clark JA, Talcott JA, Finnegan T, Mishel M, Bensen J, Rayford W, Su LJ, Fontham ET, Mohler JL: Racial differences in trust and regular source of patient care and the implications for prostate cancer screening use. Cancer 115: 5048–5059, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Musa D, Schulz R, Harris R, Silverman M, Thomas SB: Trust in the health care system and the use of preventive health services by older black and white adults. Am J Public Health 99: 1293–1299, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Williams DR, Mohammed SA: Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 32: 20–47, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS: Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. Am J Public Health 93: 200–208, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Williams DR, Neighbors H: Racism, discrimination and hypertension: Evidence and needed research. Ethn Dis 11: 800–816, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O, II: Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep 118: 293–302, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce: Missing persons: Minorities in the health professions. A report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. Available at: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/media/pdf/sullivanreport.pdf Accessed October 7, 2010

- 38. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C: The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood) 21: 90–102, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Patterson DG, Carline JD: Promoting minority access to health careers through health profession-public school partnerships: A review of the literature. Acad Med 81: S5–S10, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rumala BB, Cason FD, Jr: Recruitment of underrepresented minority students to medical school: Minority medical student organizations, an untapped resource. J Natl Med Assoc 99: 1000–1004, 1008–1009, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Price EG, Gozu A, Kern DE, Powe NR, Wand GS, Golden S, Cooper LA: The role of cultural diversity climate in recruitment, promotion, and retention of faculty in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med 20: 565–571, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.