Abstract

Our interest was drawn to the I–II loop of CaV3 channels for two reasons: (1) transfer of the I–II loop from a high voltage-activated channel (CaV2.2) to a low voltage-activated channel (CaV3.1) unexpectedly produced an ultra-low voltage activated channel; and (2) sequence variants of the I–II loop found in childhood absence epilepsy patients altered channel gating and increased surface expression of CaV3.2 channels. To determine the roles of this loop we have studied the structure of the loop and the biophysical consequences of altering its structure. Deletions localized the gating brake to the first 62 amino acids after IS6 in all three CaV3 channels, establishing the evolutionary conservation of this region and its function. Circular dichroism was performed on a purified fragment of the I–II loop from CaV3.2 to reveal a high α-helical content. De novo computer modeling predicted the gating brake formed a helix-loop-helix structure. This model was tested by replacing the helical regions with poly-proline-glycine (PGPGPG), which introduces kinks and flexibility. These mutations had profound effects on channel gating, shifting both steady-state activation and inactivation curves, as well as accelerating channel kinetics. Mutations designed to preserve the helical structure (poly-alanine, which forms α-helices) had more modest effects. Taken together, we conclude the second helix of the gating brake establishes important contacts with the gating machinery, thereby stabilizing a closed state of T-channels, and that this interaction is disrupted by depolarization, allowing the S6 segments to spread open and Ca2+ ions to flow through.

Key words: calcium channels, epilepsy, ion channel gating, membrane potentials, molecular sequence data, mutation, protein structure

Chimeric Studies Revealed Important Properties of the I–II Loop

The I–II loop in high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels plays a major role in channel function. It contains binding sites for both its β subunits (CaVβ) and G protein βγ subunits. Binding of CaVβ subunits increases trafficking of the α1 subunits of CaV1 and CaV2 families to the plasma membrane, increases channel Po, and modulates the time- and voltage-dependence of channel gating.1 While binding of G protein βγ subunits to the I–II loop inhibit activity of the family of CaV2 channels.2 The amino acid sequence of the I–II loop differs significantly for the CaV3 family. CaV3 channels have lost the ability to bind β subunits with high affinity, and therefore, they have lost CaVβ regulation. We hypothesized that transfer of the I–II loop from a CaVβ-regulated high voltage-activated channel (CaV2.2) to a CaVβ-independent low voltage-activated channel (CaV3.1) would restore CaVβ regulation. Much to our surprise we created an ultra-low voltage activated channel.3 As predicted the chimera did retain some features of CaVβ regulation, e.g., slowing of inactivation kinetics and shifts in the voltage-dependence of activation. In an effort to improve CaVβ regulation we also transferred the distal part of the IS6 segment from CaV2.2, testing the hypothesis that a glycine hinge (GxxxG4) in α12.2 was important for regulation. Again, to our surprise we nearly abolished open state inactivation and in so doing abolished the transient nature that defines T-currents.3 This finding reveals an important role of the distal IS6 segment in T-channel gating, which is similar to the results found for its IIIS6 segment.5 Nevertheless, CaVβ regulation was not improved. We next tested the hypothesis that CaVβ regulates channel activity by altering the movement of IS6, an effect mediated by a rigid α-helix. To test this hypothesis we replaced six consecutive residues of this α-helix with glycine residues (G6) that destabilize helices. As a control we replaced six consecutive residues alanine (A6) that preserve α-helical structure and hence function.6,7 Circular dichroism studies confirmed the α-helical structure of the wild-type CaV2.2 IS6 to alpha-interaction domain (AID), its preservation by A6, and its destruction by G6. Notably, CaVβ regulation was abolished by the G6 substitution and maintained in the A6 mutant, thereby providing the first evidence that CaVβ subunits modulate Ca2+ channel gating by direct communication with the IS6 segment. Interestingly, deletion of a single amino acid in this linker abolishes both CaVβ and G protein regulation of CaV2.2 (Bdel1,8,9). Bimolecular f luorescence complementation studies confirmed that this deletion altered the orientation of CaVβ with respect to the α1 subunit, strongly suggesting that orientation is critical for aligning multiple points of contact between the two subunits. For a comprehensive review of CaVβ structure and function, see the review written by Buraei and Yang.1

The Role of the I–II Loop in Surface Expression: A Novel Paradigm for Childhood Absence Epilepsy Variants

The three CaV3 channels are expressed throughout the central nervous system, displaying both overlapping and complementary expression.10,11 For example in the thalamus, CaV3.2 and CaV3.3 mRNAs are expressed in the reticular nucleus, while CaV3.1 mRNA is abundantly expressed in the relay nuclei. T-channels play important roles as pacemaker currents, depolarizing the plasma membrane enough to trigger bursts of Na-dependent action potentials. Thalamic neurons express the highest T-currents in the body and play a major role in its oscillatory rhythms.12 Therefore, sequence variations in T-channel genes may increase susceptibility to neurological disorders characterized by thalamocortical dysrhythmia.13 This hypothesis was tested by Chen and coworkers who sequenced two T-channel genes in Chinese patients with childhood absence epilepsy (CAE).14,15 Twelve variants in the gene encoding CaV3.2 (CACNA1H) were found exclusively in these patients. Many, but not all, of these variants altered the biophysical properties of the recombinant channel expressed in 293 cells.16 Computer modeling predicts that some of these variants would lead to increased neuronal firing, supporting in part the hypothesis that they contribute to the pathogenesis of this polygenic disorder. For a comprehensive review of CaV3.2 in epilepsy, see the review written by Khosravani and Zamponi.17

Since many channelopathies are due to mutations that alter trafficking, we hypothesized that the CACNA1H variants may also affect trafficking. Notably, seven of the twelve CAE specific variants alter the amino acid sequence of the I–II loop in CaV3.2. Three of these variants had a large effect on firing in the NEURON model (C456S, P648L and G773D: Vitko et al. 2005), two had little or no effect (G499S, A748V; see also Peloquin et al.18), and one decreased firing (G784S). Previous studies by Bourinet and coworker established the utility of an hemagluttinin tagged (HA) CaV3.2 channel for measuring expression of channels in intracellular compartments and at the cell surface.19 This assay relies on immunochemical detection of the HA-epitope that was introduced into the large extracellular loop connecting IS5 to the pore loop. By comparing the accessibility of the epitope in permeabilized and non-permeabilized cells one can measure changes in both total and surface expression of the channels. Introduction of the CAE variants into the tagged channels led a 20–50% increase in the surface expression over control.20 Modeling studies predict that increased T-currents would trigger thalamic oscillations, such as those observed in absence epilepsy.21 Supporting this notion are studies in animal models of absence epilepsy, which all show an increase in T-current density.22 In fact, overexpression of CaV3.1 is sufficient to trigger spontaneous seizures in mice.23 Therefore, these studies provided a unifying mechanism by which sequence variants can cause a gain in T-channel function that would contribute to seizure susceptibility. The corollary may also be important, polymorphisms in CACNA1H that decrease channel activity were found in patients with autism spectrum disorders.24 In both cases, some variants in affected patients were always found in conjunction with neighboring variants found in control patients (in CAE, G773D with R778C; in ASD, A1874V with R1871Q). These results are consistent with the polygenic inheritance of these disorders the modest effects most variants have on channel activity, and the hypothesis that common variants that alter channel activity may contribute to human disease.

Although CAE variants and deletions within I–II loop increased surface expression, these studies failed to identify a specific ER retention motif. Nevertheless, evidence that the loop does contain a protein-interaction site that impairs surface expression was obtained using a “pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey” construct where the region deleted in D1-3 was fused to the carboxy terminus of D1-3. This addition normalized current density to control values. It seems there are many regions within the I–II loop of CaV3.2 involved in regulating surface expression, and that point mutations or deletions disrupt these regions and impair its normal surface expression. A major finding of this study was that sequence variations that increase seizure susceptibility may act by increasing surface expression of CaV3.2 channels to the plasma membrane. In addition to altering neuronal excitability via its pacemaking function, increased T-channels may lead to increases in intracellular Ca2+ which in turn may affect gene transcription or surface expression.

The I–II Loop Contains a Gating Brake

To dissect the roles of the I–II loop of CaV3.2 channels in gating and surface expression, we performed deletion analysis. Specifically, we used secondary structure prediction programs to identify possible structural motifs in the loop, and then used sitedirected mutagenesis to remove these motifs in a systematic manner.20 These studies revealed that the I–II loop has two separable functions, one to alter channel gating, and another to regulate surface expression. Motifs closest to the IS6 and IIS1 transmembrane segments altered channel gating. In contrast to the modest effect of CAE variants, these deletions induced 10–15 mV shifts in the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation. Motifs in the central part of the loop had no effect on gating, but played a major role in the membrane targeting of CaV3.2 channels as their deletion increased surface expression up to 3-fold. The first 62 amino acids of the loop after IS6 (a.a. 429–491) played a key role not only in the voltage dependence of gating, but also on channel kinetics, accelerating both activation and inactivation. We conclude that this conserved region forms an intracellular gating particle. This gating particle appears to act like a brake, as its removal allowed channels to open at more negative voltages.

The Function of the Gating Brake is Conserved in all Three CaV3 Channels

Sequence alignments show that the first 62 a.a. after IS6 are highly conserved in all CaV3 channels from snail to man (Fig. 1), leading to the attractive hypothesis that the gating brake is conserved. To address this hypothesis, we explored the role of the I–II loop in human CaV3.1 and CaV3.3 channels.25 As predicted, deletion of the gating brake in all three CaV3 channels produced large 10–15 mV shifts in the voltage dependence of gating and accelerated activation and inactivation kinetics. To explore the role of the I–II loop in channel trafficking, we used the same strategy as with CaV3.2, introducing the HA epitope into the extracellular loop connecting IS5 to the pore loop, and measuring surface expression with anti-HA antibodies. Unexpectedly, deletions of the I–II loop that only affected trafficking in CaV3.2 channels only modestly increased trafficking of CaV3.1 yet decreased trafficking of CaV3.3. Notably, amino acid conservation follows a similar pattern, with CaV3.1 and CaV3.2 showing considerable identity, while CaV3.3 has a much smaller loop (204 vs. 372 a.a.). This study also revealed important differences in the surface expression of wild-type CaV3 channels, as only 13% of wild-type CaV3.2 channels were expressed at the surface, while 25% and 34% of CaV3.1 and CaV3.3 channels were expressed at the surface, respectively. It is interesting to speculate that trafficking of CaV3.2 channels is regulated by extrinsic factors, and underlies the increase in T-currents observed in several disease states, such as temporal lobe epilepsy26 and diabetic neuropathy.27

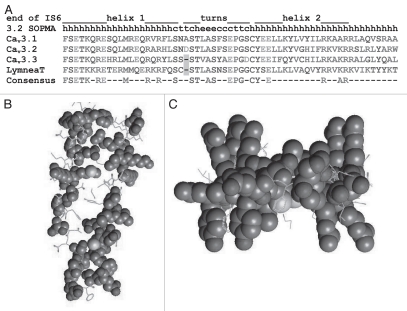

Figure 1.

Conservation of the gating brake. (A) Alignment of the three human CaV3 amino acid sequences to that determined for the freshwater pond snail, Lymnaea stagnalis. The location of helix-turn-helix of the gating brake is shown above, and secondary structure prediction by the SOPMA algorithm.41 Bottom line shows consensus sequence for residues that are identical in all four sequences. Amino acids are colored based on their physical properties to emphasize conservative amino acid changes. (B) Model of the CaV3.2 I–II loop gating brake with residues conserved in Lymnea displayed in Corey-Pauling-Koltun (CPK) space filling model. Model was originally reported by Arias et al.29 and modified according to the Lymnea sequence reported by Senatore and Spafford.42 The model is viewed from the side, with the plasma membrane on top and helix to the left. Note how conserved residues face away from the hydrophobic core, suggesting they form conserved protein-protein contacts. Substitutions in the core are conservative—hydrophobic for hydrophobic and the putative salt bridge is conserved. (C) Second view of the model is from the bottom looking up at the membrane. Note how the conserved “arginine fingers” jut out perpendicular to the plane of the gating brake. These residues are comprised of five Arg residues on one face and two on the other.

Structure of the Gating Brake

Secondary structure prediction programs suggest the first 62 amino acids that compose the gating brake would form a helixloop-helix structure similar to that found in fumarase.28 To test this prediction we purified a fragment of the I–II loop from E. coli, and studied its structure using circular dichroism.29 The circular dichroism spectrum indicated that the proximal I–II loop contains a high α-helical content, essentially matching the predicted value.

Four types of mutations were used to test the helix-loop-helix model. First, we used deletion analysis to find the distal end of the gating brake.29 Second, we tested for the existence of α-helical regions by replacing 6 consecutive amino acids with prolines and glycines to disrupt the helix, and as a control we replaced the same residues with alanine to conserve the helix. Third, we tested for the existence of the loop by either converting it to an α-helix, or by deleting it entirely, effectively fusing helix 1 to helix 2. Finally, we also tested whether addition of alanines to the middle of helix 1 would alter the pitch of the helix, and thereby alter the orientation of the helix-loop-helix with respect to the channel. Overall, the results were consistent with the helix-loop-helix model, as disruption of any of this structure recapitulated the same phenotype: channels whose voltage dependence of activation and inactivation were shifted 10–15 mV and accelerated kinetics. Surprisingly, the poly-alanine mutations also affected function. This finding suggests that the mutated residues play an additional role other than forming an α-helix, possibly forming points of contact with other parts of the gating machinery.

3-D Model of the Brake

To interpret our findings, we generated three dimensional models of the gating brake and examined how the mutations affected its structure.29 Specifically, we constructed de novo models obtained using the Quanta program and molecular dynamics simulations using HyperChem 7.1. The predicted structure supported the hypothesis that the gating brake forms a helix-loop-helix structure. The models provided insights into the structural modifications caused by the mutations. For example, the poly-alanine mutations disrupted function greater than predicted if this region were a simple helix, and the model shows the loss of a salt bridge between E429 and both K470 and R473. The model also predicted the end of the gating brake, coinciding perfectly with the experimental results. Our studies of the loop region were complicated by the presence of two putative hair-pin turns, since only one turn would be required to orient helix 2 in an antiparallel manner with respect to helix 1. Indeed, replacement of either turn region with six alanines produced channels with only modest effects on gating. In contrast, mutation of both turn regions or deletion of the entire loop region (DC1), produced dramatic shifts in gating. The modeling studies agree well with the experimental findings: replacement of either turn was insufficient to disrupt the helix-loop-helix structure due to compensation by the remaining turn. Modeling of DC1 indicates that the loop was effectively removed, and that helix 1 was fused to helix 2. The gating phenotype of this mutant is similar to the D2 mutant (which lacks helix 2); therefore, we infer that function of the gating brake was totally disrupted. The model also predicts that the epilepsy mutation, C456S, is at a critical location in the brake, forming the start of helix 2, and projecting towards helix 1.

Proposed Mechanism of Action of the Gating Brake

Taken together, our studies establish that the first 62 amino acids immediately following the IS6 segment plays the role of a gating brake in all three CaV3 channels. We called it a gating brake since if appears to stabilize channels in the closed state, and disruption of its function leads to channels that open at normal membrane potentials. Similarly, destabilization of the closed state was proposed to explain how mutations in hydrophobic residues in the S4 voltage sensor of K+ channels shifted gating to more negative voltages.30 Deletion of the gating brake also led to faster channel opening and increased iPo as predicted by this hypothesis.

Previous measurements of T-channel gating currents indicate that 80% of the channels open after only 20% of total charge movement.31,32 This suggests that T-channels open after minimal movement of their voltage sensors and modeling studies suggest this might explain why T-channel kinetics are so voltage-dependent.32–34 We propose two mechanisms by which the brake region stabilizes the closed state. These models were developed by superimposing the gating brake on the crystal structure of the KV1.2–KV2.1 paddle chimera channel.35 In one version, the gating brake is oriented towards the S6 segments of other repeats (Fig. 2A). Voltage-gated channels are now accepted to have two gates, one at the pore loop and the second at the intracellular crossing of the S6 bundles.36 We suggest that the T-channel S6 segments form an internal gating ring similar to that determined for K+ channels,37 and that the gating brake acts on this intracellular gate. The model shows how the gating brake could reach both II6 and IIIS6. Support for an S6 gating ring comes from studies showing that mutations in S6 segments slow open channel inactivation3,5 as observed in HVA channels.38–40 A second scenario is that the gating brake is oriented in the opposite direction (X–Y plane), facing the IS1-S4 voltage-sensing paddle (Fig. 2B). In this manner it could interact directly with the S4–S5 linker, which plays a major role in coupling S4 voltage-sensor movement to opening of the lower S6 gate. The model also predicts that in either orientation the gating brake would lie over the IS1-S4 gating paddle. A limitation of these models is that the orientation of the gating brake in the Z-axis is unknown. Therefore we make the assumption that the orientation of the S6 segment is the same as observed in the KV crystal structure, which projects horizontally with respect to the membrane. It is tempting to speculate that the conserved positively charged residues at the end of helix 2 (Fig. 1) are important for this interaction. Interestingly, deletion of the gating brake in CaV3.3 induces a large −35 mV shift in the gating current-voltage relationship (Karmazinova M and Lacinová L, unpublished observations). At first glance it seems unlikely the gating brake could shift the entire G(V) curve by interaction with a single S4 paddle, yet closer examination of voltage-gated K+ channel structures reveals an interdigitation between subunits, resulting in an extended hot-spot where the three repeats converge.36 In this manner, the gating brake could interact with not only repeat I machinery, but also interact with repeats II and IV, and thereby affect movements in 3 of the 4 repeats (Fig. 2C and D). In addition, an allosteric model with coupling of the S4 voltage sensors could account for this large shift in the G(V) curve.

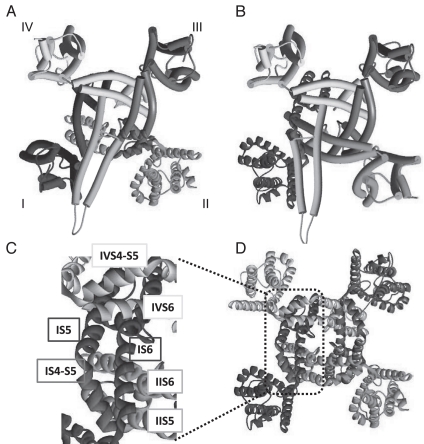

Figure 2.

Two models of the gating brake. (A) The model of the gating brake (light blue) was superimposed on the crystal structure of the KV1.2–KV2.1 paddle chimera (PDB #2R9R).35 View is from the inside of the cell facing the membrane. The gating brake model begins with the glycine-serine motif in the middle of IS6—a conserved motif observed to form a hinge in the MthK crystal structure.43 It was then superimposed on the threonine-isoleucine motif in the KV1.2 channel (alignment by Jan and Jan).44 In this manner the orientation of the gating brake with respect to IS6 is the same as the extension of S6 in the crystal structure. IIS5 and S6 are highlighted in red to emphasize possible contacts with helix 2 of the gating brake. (B) Here the gating brake has been flipped 180°, resulting in possible helix 2 contacts with the IS4-S5 (red). (C and D) Location of the contact points between repeats IV, I and II as deduced from the same KV crystal structure.

In conclusion, the I–II loops of T-channels play critical roles in the trafficking and gating of these channels. This loop contains an intracellular gating brake that is essential to their ability open after small depolarizations of the membrane. Finally, the ability of sequence variants of the I–II loop to alter gating and trafficking provides insights into how these variations increase seizure susceptibility.

Acknowledgements

These studies would not have been possible without the hard work of post-docs and graduate students who worked in my lab and that of my international collaborators. Specifically, and chronologically, I would like to acknowledge the work of Juan Manuel Arias and Janet Murbartiαn for the early chimeric studies; Isabelle Bidaud, Alexandre Mezghrani and Philippe Lory for their contributions to the trafficking story; Joel Baumgart for his dissertation study of CaV3.1 and CaV3.3; Imilla I. Arias-Olguín for her dissertation study of CaV3.2; Manuel Soriano-Garcia for computer modeling; Svetlana Sokolova and Igor Shumilin for structural characterization of the gating brake; Maria Karmazinova and L'ubica Lacinova for providing unpublished results on the gating currents; Eduardo Perozo, Michal Fortuna and Juan Carlos Gomora for helpful discussions; and last, but not least, to Iuliia Vitko, who played a key role in all of these studies. This work was supported by NIH grants NS038691 and NS067456.

References

- 1.Buraei Z, Yang J. The β-subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1461–1506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamponi GW, Bourinet E, Nelson D, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Crosstalk between G proteins and protein kinase C mediated by the calcium channel a1 subunit. Nature. 1997;385:442–446. doi: 10.1038/385442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias JM, Murbartián J, Vitko I, Lee JH, Perez-Reyes E. Transfer of β subunit regulation from high to low voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3907–3912. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raybaud A, Dodier Y, Bissonnette P, Simoes M, Bichet DG, Sauve R, et al. The role of the GX9GX3G motif in the gating of high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39424–39436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marksteiner R, Schurr P, Berjukow S, Margreiter E, Perez-Reyes E, Hering S. Inactivation determinants in segment IIIS6 of CaV3.1. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;537:27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0027k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacArthur MW, Thornton JM. Influence of proline residues on protein conformation. J Mol Biol. 1991;218:397–412. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90721-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Neil KT, DeGrado WF. A thermodynamic scale for the helix-forming tendencies of the commonly occurring amino acids. Science. 1990;250:646–651. doi: 10.1126/science.2237415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitko I, Shcheglovitov A, Baumgart JP, Arias-Olguín II, Murbartián J, Arias JM, et al. Orientation of the calcium channel β relative to the α12.2 subunit is critical for its regulation of channel activity. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:3560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitra-Ganguli T, Vitko I, Perez-Reyes E, Rittenhouse AR. Orientation of palmitoylated CaVβ2a relative to CaV2.2 is critical for slow pathway modulation of N-type Ca2+ current by tachykinin receptor activation. J Gen Physiol. 2009;134:385–396. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talley EM, Cribbs LL, Lee JH, Daud A, Perez-Reyes E, Bayliss DA. Differential distribution of three members of a gene family encoding low voltage-activated (T-type) calcium channels. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1895–1911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01895.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKay BE, McRory JE, Molineux ML, Hamid J, Snutch TP, Zamponi GW. CaV3 T-type calcium channel isoforms differentially distribute to somatic and dendritic compartments in rat central neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;24:2581–2594. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated T-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:117–161. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llinás R, Ribary U, Jeanmonod D, Cancro R, Kronberg E, Schulman J, et al. Thalamocortical dysrhythmia I. Functional and imaging aspects. Thalamus & Related Systems. 2001;1:237–344. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Lu J, Zhang Y, Pan H, Wu H, Xu K, et al. T-type calcium channel gene α1G is not associated with childhood absence epilepsy in the Chinese Han population. Neurosci Lett. 2003;341:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen YC, Lu JJ, Pan H, Zhang YH, Wu HS, Xu KM, et al. Association between genetic variation of CACNA1H and childhood absence epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:239–243. doi: 10.1002/ana.10607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitko I, Chen Y, Arias JM, Shen Y, Wu XR, Perez-Reyes E. Functional characterization and neuronal modeling of the effects of childhood absence epilepsy variants of CACNA1H, a T-type calcium channel. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4844–4855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0847-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khosravani H, Zamponi GW. Voltage-gated calcium channels and idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:941–966. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peloquin JB, Khosravani H, Barr W, Bladen C, Evans R, Mezeyova J, et al. Functional analysis of CaV3.12 T-type calcium channel mutations linked to childhood absence epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:655–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubel SJ, Altier C, Chaumont S, Lory P, Bourinet E, Nargeot J. Plasma membrane expression of T-type calcium channel α1 subunits is modulated by HVA auxiliary subunits. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29263–29269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313450200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vitko I, Bidaud I, Arias JM, Mezghrani A, Lory P, Perez-Reyes E. The I–II loop controls plasma membrane expression and gating of CaV3.2 T-type Ca2+ channels: a paradigm for childhood absence epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2007;27:322–330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1817-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormick DA, Huguenard JR. A model of the electrophysiological properties of thalamocortical relay neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:1384–1400. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.4.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Mori M, Burgess DL, Noebels JL. Mutations in high-voltage-activated calcium channel genes stimulate low-voltage-activated currents in mouse thalamic relay neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6362–6371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06362.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ernst WL, Zhang Y, Yoo JW, Ernst SJ, Noebels JL. Genetic enhancement of thalamocortical network activity by elevating α1G-mediated low-voltage-activated calcium current induces pure absence epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1615–1625. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2081-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Splawski I, Yoo DS, Stotz SC, Cherry A, Clapham DE, Keating MT. CACNA1H mutations in autism spectrum disorders. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22085–22091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumgart JP, Vitko I, Bidaud I, Kondratskyi A, Lory P, Perez-Reyes E. I–II loop structural determinants in the gating and surface expression of low voltage-activated calcium channels. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:2976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su H, Sochivko D, Becker A, Chen J, Jiang Y, Yaari Y, et al. Upregulation of a T-type Ca2+ channel causes a long-lasting modification of neuronal firing mode after status epilepticus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3645–3645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03645.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagodic MM, Pathirathna S, Nelson MT, Mancuso S, Joksovic PM, Rosenberg ER, et al. Cell-specific alterations of T-type calcium current in painful diabetic neuropathy enhance excitability of sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3305–3316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4866-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ginalski K, Elofsson A, Fischer D, Rychlewski L. 3D-Jury: a simple approach to improve protein structure predictions. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1015–1018. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arias-Olguín II, Vitko I, Fortuna M, Baumgart JP, Sokolova S, Shumilin IA, et al. Characterization of the gating brake in the I.II loop of CaV3.2 T-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8136–8144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708761200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liman ER, Hess P, Weaver F, Koren G. Voltage-sensing residues in the S4 region of a mammalian K+ channel. Nature. 1991;353:752–756. doi: 10.1038/353752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lacinová L, Klugbauer N, Hofmann F. Gating of the expressed CaV3.1 calcium channel. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:235–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam AD, Chikina MD, McNulty MM, Glaaser IW, Hanck DA. Role of domain IV/S4 outermost arginines in gating of T-type calcium channels. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:349–361. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talavera K, Nilius B. Evidence for common structural determinants of activation and inactivation in T-type Ca2+ channels. Pflugers Arch. 2006;453:189–201. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frazier CJ, Serrano JR, George EG, Yu X, Viswanathan A, Perez-Reyes E, et al. Gating kinetics of the α1I T-type calcium channel. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:457–470. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.5.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long SB, Campbell EB, Mackinnon R. Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science. 2005;309:897–903. doi: 10.1126/science.1116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SY, Banerjee A, Mackinnon R. Two separate interfaces between the voltage sensor and pore are required for the function of voltage-dependent K+ channels. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:47. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yellen G. The voltage-gated potassium channels and their relatives. Nature. 2002;419:35–42. doi: 10.1038/nature00978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi C, Soldatov NM. Molecular determinants of voltage-dependent slow inactivation of the Ca2+ channel. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6813–6821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stotz SC, Jarvis SE, Zamponi GW. Functional roles of cytoplasmic loops and pore lining transmembrane helices in the voltage-dependent inactivation of HVA calcium channels. J Physiol. 2004;554:263–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, Decher N, Kumar P, Bloise R, et al. CaV1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geourjon C, Deleage G. SOPMA: significant improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by consensus prediction from multiple alignments. Comput Appl Biosci. 1995;11:681–684. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/11.6.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senatore A, Spafford JD. Transient and big are key features of an invertebrate T-type channel (LCaV3) from the central nervous system of Lymnaea stagnalis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7447–7458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The open pore conformation of potassium channels. Nature. 2002;417:523–526. doi: 10.1038/417523a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jan LY, Jan YN. A superfamily of ion channels. Nature. 1990;345:672. doi: 10.1038/345672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]