Abstract

Pyrethroid insecticides are classified as type I or type II based on their distinct symptomology and effects on sodium channel gating. Structurally, type II pyrethroids possess an α-cyano group at the phenylbenzyl alcohol position, which is lacking in type I pyrethroids. Both type I and type II pyrethroids inhibit deactivation consequently prolonging the opening of sodium channels. However, type II pyrethroids inhibit the deactivation of sodium channels to a greater extent than type I pyrethroids inducing much slower decaying of tail currents upon repolarization. The molecular basis of type II-specific action, however, is not known. Here we report the identification of a residue G1111 and two positively charged lysines immediately downstream of G1111 in the intracellular linker connecting domains II and III of the cockroach sodium channel that are specifically involved in the action of type II pyrethroids, but not in the action of type I pyrethroids. Deletion of G1111, a consequence of alternative splicing, reduced the sodium channel sensitivity to type II pyrethroids, but had no effect on channel sensitivity to type I pyrethroids. Interestingly, charge neutralization or charge reversal of two positively charged lysines (Ks) downstream of G1111 had a similar effect. These results provide the molecular insight into the type II-specific interaction of pyrethroids with the sodium channel at the molecular level.

Keywords: Type I and II pyrethroids, Deltamethrin, Permethrin, Oocytes, Sodium channel

Introduction

Pyrethroids constitute one of the most widely used classes of insecticides worldwide. They are synthetic structural derivatives of natural pyrethrins present in the pyrethrum extract of Chrysanthemum species (Elliott, 1977). The primary target of pyrethroid insecticides is the voltage-gated sodium channel, which is essential for the initiation and propagation of action potentials in almost all excitable cells. Extensive electrophysiological and pharmacological studies on the mode of action of pyrethroids have been conducted over the past several decades. Collectively, these studies show that pyrethroids cause prolonged opening of sodium channels primarily by inhibiting channel deactivation, thereby stabilizing the open configuration of the activation gate (Vijverberg et al., 1982; Narahashi, 1996).

The classification of pyrethroids as type I and type II was first introduced by Casida and associates based on the distinct poisoning symptoms and effects on the cercal sensory nerve of Periplaneta americana, the American cockroach (Gammon et al., 1981). Structurally, type I and type II pyrethroids differ mainly in the absence (type I) or the presence (type II) of an α-cyano group at the phenylbenzyl alcohol position (Fig. 1). Type I pyrethroids generally induced repetitive firing of the cockroach cercal sensory nerves following a single electrical stimulus, whereas type II pyrethroids did not induce such repetitive firing. Furthermore, cockroaches dosed with type I pyrethroids exhibited restlessness, incoordination, hyperactivity, prostration, and paralysis. Type II pyrethroid-intoxicated insects, in addition to signs of ataxia and incoordination, showed some unique symptoms including a pronounced convulsive phase (Gammon et al., 1981). Electrophysiological analyses of the effects of type I and type II pyrethroids on sodium channels in vertebrate and invertebrate nerve preparations confirmed the divergent action of type I and type II pyrethroids (Lund and Narahashi, 1981; Vijverberg et al., 1982). Type I pyrethroids cause repetitive discharges in response to a single stimulus, while type II pyrethroids caused a membrane depolarization accompanied by a suppression of the action potential (Lund and Narahashi, 1981). Furthermore, voltage-clamp experiments (Lund and Narahashi, 1981; Vijverberg et al., 1982) demonstrated that type II pyrethroids inhibit the deactivation of sodium channels to a greater extent than type I pyrethroids. The decay of tail currents induced by type II pyrethroids is at least one order of magnitude slower than those induced by type I pyrethroids. This quantitative differences in tail current decay kinetics between type I and type II pyrethroids could account for their different action on the whole nerve system (Narahashi, 1988).

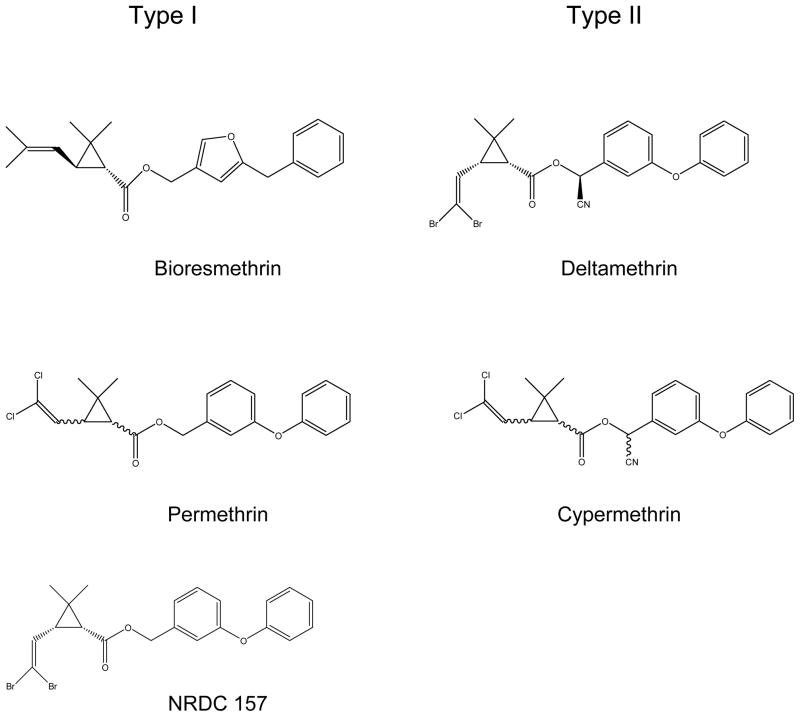

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of five pyrethroids used in this study. Bioresmethrin and permethrin are type I pyrethroid insecticides. Cypermethrin and deltamethrin are type II pyrethroids. NRDC157 is a deltamethrin analogue lacking the α-cyano group.

Like their mammalian counterparts, insect sodium channels are large transmembrane proteins composed of four homologous domains (I to IV), each domain consisting of six transmembrane segments (S1 to S6) (Fig. 2A). Studies on the molecular mechanisms of knockdown resistance (kdr), a major form of insect resistance to pyrethroids, have greatly improved our understanding of the interaction between pyrethroids and sodium channels at the molecular level (Soderlund and Knipple, 2003). Multiple point mutations were found in insect sodium channels of pyrethroid-resistant insect populations (Soderlund, 2005; Davies et al., 2007; Dong, 2007). Many kdr mutations have been shown to reduce the sensitivities of insect sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes to various pyrethroids (Soderlund, 2005; Davies et al., 2007; Dong, 2007). Furthermore, two kdr mutations were shown to reduce pyrethroid binding, suggesting that the corresponding amino acid residues are part of the pyrethroid receptor site (Tan et al., 2005). So far, however, all confirmed kdr mutations affect the action of both type I and type II pyrethroids, suggesting similar molecular determinants in the binding/action of both type I and type II pyrethroids.

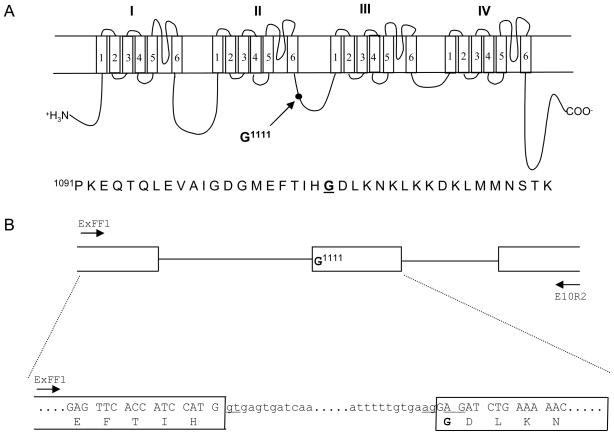

Figure 2.

Exclusion of G1111 is the result of alternative splicing. A. Schematic drawing of the cockroach sodium channel indicating the position of G1111. A stretch of amino acid sequence flanking G1111 (bold and underlined) is shown below, starting with amino acid residue 1086 of BgNav1-1. B. The exon-intron structure of the 1.8 kb genomic fragment where G1111 (bold) is located. The splicing consensus sites, including the alternative ag/AG sites, are underlined. Primers used to amplify genomic DNA are indicated with arrows. The nucleotide sequence of the 1.8 kb genomic fragment is deposited in the GenBank under the accession number: DQ466887.

In this study we found that nineteen splice variants of the cockroach sodium channel (BgNav) lacked a glycine (G) at position 1111 in the second linker connecting domains II and III (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, lack of G1111 made the BgNav channel more resistant to type II pyrethroids, but not to type I pyrethroids. Furthermore, neutralization of the two lysines (Ks) immediately downstream of G1111 also reduced the sensitivity of the channel to type II pyrethroids without affecting the sensitivity to type I pyrethroids. These results provide the first insight into the type-specific interaction of pyrethroids with the sodium channel at the molecular level.

Materials and methods

Genomic DNA was isolated from the heads of an insecticide-susceptible German cockroach strain (CSMA; generously provided by Dr. J. G. Scott, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) using the protocol described by Dong and Scott (1994). For amplifying genomic DNA encoding the linker connecting domains II and III, a pair of primers was designed based on the BgNav cDNA sequence: ExFF1: aca cgg acc ttg acc tca c (sense) and E10R2: ctt ttc ctc ccc atc cat agt c (antisense) (Fig. 2B). Amplification of genomic DNA was performed in a 50 μl polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mix containing 0.2 μg of genomic DNA, 50 pmol of each primer, 200 μM each dNTP, and 1 U eLONGase (Invitrogen). The PCR conditions were 30 cycles of 30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 58°C, and 10 min at 68°C. The Prep-A-Gene kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used to isolate the PCR products from agarose gel for cloning or direct sequencing. The amplified DNA fragment was sequenced in the Research Technology Support Facility at Michigan State University.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by PCR using mutant primers and Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All mutagenesis results were verified by DNA sequencing.

The procedures for oocyte preparation and cRNA injection were identical to those described by Tan et al (2002a, b). For robust expression of the cockroach BgNav sodium channels, BgNav cRNA was co-injected into oocytes with cRNA of D. melanogaster tipE (1:1 molar ratio), which is known to enhance the expression of insect sodium channels in oocytes (Feng et al., 1995).

All oocyte recordings were performed at room temperature (20–22°C) in ND96 bath solution (96.0 mM NaCl; 2.0 mM KCl; 1.8 mM CaCl2; 1.0 mM MgCl2; 10.0 mM HEPES, adjust pH to 7.5 with 2N NaOH). Recording electrodes were prepared from borosilicate glass using a p-87 puller (Sutter instrument, Novato). Microelectrodes were filled with filtered 3M KCl/0.5% agarose and had resistances between 0.4 and 1.0 MΩ. Currents were recorded and analyzed using the oocyte clamp instrument OC725C (Warner Instrument Corp., CT), Digidata 1322A interface (Axon Instrument, CA), and pClamp 8.2 software (Axon instruments, CA). The data were filtered at 2 kHz on-line and digitized at a sampling frequency of 20 kHz. Leak currents were corrected by P/4 subtraction. The maximal peak sodium current was limited to < 2.0 μA to achieve better voltage control by adjusting the amount of cRNA injected into oocytes and the incubation time after injection. The voltage-dependence of activation and fast inactivation were determined using the protocols described in Tan et al. (2002a, b). The data were fitted with a Boltzmann equation to generate V1/2, the midpoint of the activation or inactivation, and k, the slope factor.

Pyrethroids inhibit deactivation of sodium channels, consequently inducing large tail currents upon repolarization. The amplitude and decay of tail currents are two major parameters to quantify the action of pyrethroids. To record deltamethrin-induced tail currents, we applied a 100-pulse train of 5-ms depolarizations from −120 mV to −10 mV, as described by Vais et al. (2000). Because pyrethroids preferably binds to sodium channels in the open state, a 100-pulse train of 5-ms inter-pulse intervals was used to increase the availability of open channels. The method for pyrethroid application was identical to that described in Tan et al. (2002a, b). The working concentration was prepared in ND96 recording solution just prior to application. The concentration of DMSO in the final solution was < 0.5%, which had no effect on sodium channels in the experiments. The pyrethroid-induced tail currents were measured 10 min after toxin application. Percentages of channels modified by pyrethroid were calculated using the equation (Tatebayashi and Narahashi, 1994), where Itail is the maximal tail current amplitude, Eh, ENa and Et are the holding potential, reversal potential and test potential, respectively. INa is the amplitude of the peak current during depolarization before pyrethroid exposure. Dose-response curves were fitted to the Hill equation: , in which [pyrethroid] represents the concentration of pyrethroid and EC50 represents the concentration of pyrethroid that produced the half-maximal effect, n represents the Hill coefficient, and Mmax is the maximal percentage of sodium channel modified. Because voltage-clamp fails at higher pyrethroid concentrations due to large leakage currents, we cannot obtain the upper portion of the dose-response curve. EC20s were used to compare channel sensitivities among wild-type and mutant channels. The decays of tail currents were fitted with single- or bi-exponential functions to determine time constants (Tau values), with which tail current peak amplitudes were extrapolated at the time zero where there was no overlap between capacitive and tail currents.

Results

We have shown that alternative splicing and RNA editing of BgNav are the two major mechanisms by which cockroaches and presumably other insects generate an impressive spectrum of functionally and pharmacologically distinct sodium channel variants from a single gene (Tan et al., 2002b; Liu et al., 2004; Song et al., 2004). In a previous study, using RT-PCR we isolated sixty-nine full-length cDNA clones of the cockroach sodium channel gene BgNav and grouped these clones into twenty splice types based on distinct usages of alternative exons (Song et al., 2004). Besides alternative splicing, RNA editing (both A-to-I and U-to-C editing) is also detected in various BgNav transcripts (Liu et al., 2004; Song et al., 2004) Our sequence analysis revealed that G1111 located in the middle of the second intracellular linker connecting domains II and III was missing in nineteen of the sixty-nine full-length cDNA clones (Fig. 2A). Because a lack of G1111 was detected in multiple splice types, we can rule out the possibility of an accidental error during PCR.

We investigated whether the lack of G1111 in the nineteen splice variants resulted from alternative splicing or RNA editing. The genomic DNA where the G1111 is located was PCR-amplified using the primer pair ExFF1/E10R2 (Fig. 2B). The size of the PCR product was 1.8 kb, which is much larger than the corresponding cDNA fragment (356 bp). Sequence analysis of the 1.8-kb fragment revealed two introns in this region. The consensus splice donor and acceptor sequences gt/ag were found and the codon “gga” encoding G1111 was derived from two adjacent exons, with “g” in the upstream exon and “ga” in the downstream exon. However, there is also an alternative internal acceptor sequence AG (one codon away) in the downstream exon. Therefore, the exclusion of G1111 is apparently generated by utilization of the second (inner) acceptor AG during RNA splicing (Fig. 2B).

BgNav2-1, (previously known as KD2 in Tan et al., (2002b), is one of the variants lacking G1111. We have shown that BgNav2-1 is much more resistant to deltamethrin (a type II pyrethroid) than BgNav1-1 which has G1111 (Tan et al., 2002b). To determine whether G1111 contributes to the differential sodium channel sensitivity to deltamethrin, we made two recombinant constructs: BgNav1-1G− and BgNav2-1G+, which contain a deletion of G1111 in BgNav1-1 and an addition of G1111 in BgNav2-1, respectively. The recombinant channels were expressed in oocytes and examined for gating properties and sensitivity to deltamethrin. The deletion or insertion of G1111 did not alter the voltage-dependence of activation or steady-state inactivation (Table 1). The sensitivity to pyrethroids was evaluated by measuring the amplitudes of tail currents induced by pyrethroids and quantifying the percentages of modified sodium channels by pyrethroids, as described in Experimental Procedures. Deletion of G1111 in BgNav1-1 made the mutant channel, BgNav1-1G−, about 8-fold more resistant than BgNav1-1. Similarly, addition of G1111 into BgNav2-1 made the BgNav2-1G+ channel about 8-fold more sensitive to deltamethrin (Fig. 3C). The deltamethrin-induced tail currents of BgNav1-1 decayed very slowly with two components (Fig. 3A; Table 2), typical for tail currents induced by type II pyrethroids (Vais et al., 2000; Tan et al., 2005). Deletion of G1111 did not significantly alter the decay of the tail current (Fig. 3B; Table 2).

Table 1.

Gating properties of recombinant channels in comparison with parental BgNav1-1 and BgNav2-1 channels

| Na+ Channel | Activation | Inactivation | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1/2(mV) | K(mV) | V1/2(mV) | K(mV) | ||

| BgNav2-1 | −20.7 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | −45.6 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 10 |

| BgNav2-1G+ | −24.1 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | −46.2 ± 0.4 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 10 |

| BgNav1-1 | −25.4 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | −43.5 ± 0.7 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 14 |

| BgNav1-1G− | −25.6 ± 1.3 | 5.4 ± 0.8 | −44.7 ± 0.9 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 18 |

| BgNav1-1Δβ | −25.5 ± 1.2 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | −41.9 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 8 |

| BgNav1-13k→3Q | −23.6 ± 0.7 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | −42.2 ± 0.7 | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 6 |

| BgNav1-15k→5Q | −24.3 ± 1.1 | 5.8 ± 0.9 | −42.5 ± 0.8 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 14 |

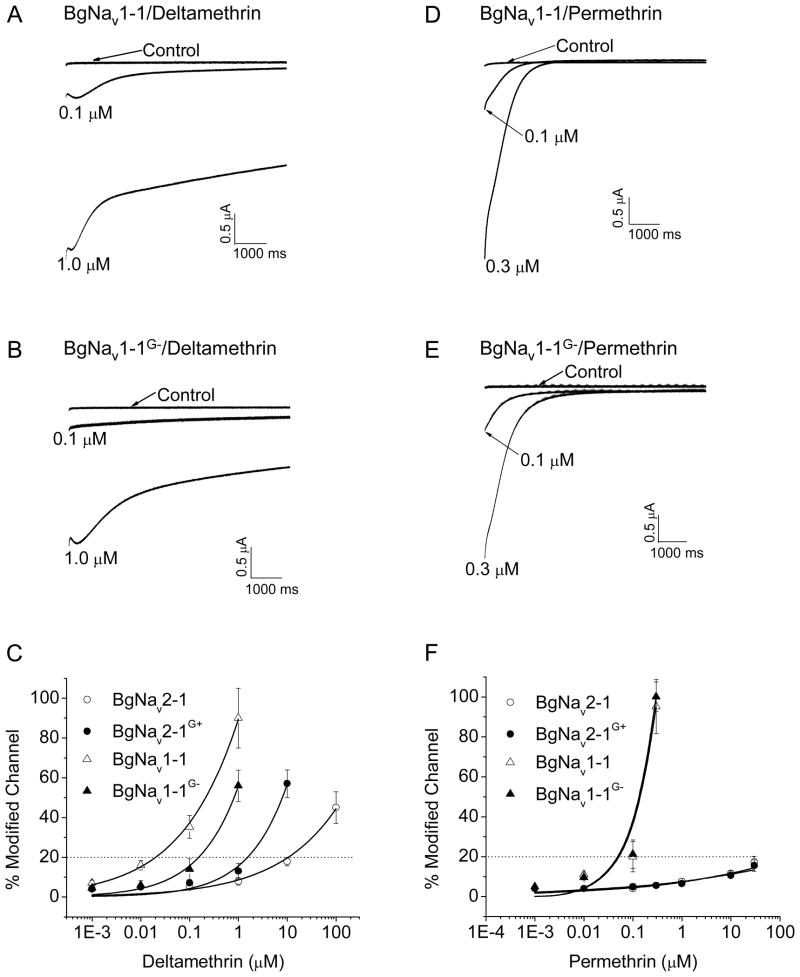

Figure 3.

Deletion of G1111 altered the sensitivity of BgNav1-1 channels to deltamethrin, but not to permethrin. A, B, D and E. Deltamethrin/permethrin-induced tail currents from oocytes expressing BgNav1-1 (A/D), and BgNav1-1G− (B/E) channels. C and F. Dose-response curves of BgNav1-1 and BgNav2-1 parental and mutant channels to delamethrin (C) and permethrin (F). Percentage modification by pyrethroids was calculated using the equation (Tatebayashi and Narahashi, 1994) Dose response curves were fitted to the Hill equation: as described in Experimental Procedures. EC20s of deltamethrin were 0.02, 0.15, 1.5, and 11.2 μM, respectively, for BgNav1-1, BgNav1-1G−, BgNav2-1, and BgNav2-1G+.

Table 2.

Time constants of the decay of pyrethroid-induced tail currents

| Pyrethroidsa | BgNav1-1 | BgNav1-1G− | BgNav1-15k→5Q | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ1(s) | τ2(s) | τ1(s) | τ2(s) | τ1(s) | τ2(s) | |

| Deltamethrin | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.30 ± 0.08 |

| Cypermethirn | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.31 ± 0.03 |

| Permethrin | 0.50 ± 0.18 | 0.55 ± 0.17 | 0.56 ± 0.16 | |||

| Bioresmethrin | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | |||

| NRDC157 | 0.56 ± 0.10 | 0.57 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.10 | |||

Deltamethrin- and cypermethrin- induced tail currents were fitted with bi-exponential functions. Permethrin-, bioresemethrin- and NRDC157- induced tail currents were fitted with single exponentials. Each value represents the mean ± S.D. Time constants of the decay of pyrethroid-induced tail currents in BgNav1-1G− and BgNav1-15k→5Q channels were not significantly different from the parental channels, BgNav1-1 (p<0.05, student t-test).

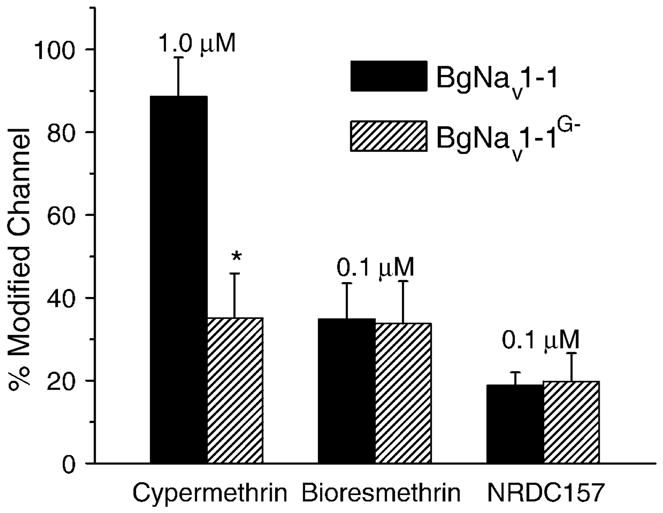

To determine whether G1111 also affects sodium channel sensitivity to other pyrethroids, we first examined the sensitivities of the BgNav1-1 and BgNav1-1G− channels to permethrin, a type I pyrethroid. As illustrated in Fig. 1, type I and type II pyrethroids differ mainly in the absence (type I) or the presence (type II) of an α-cyano group at the phenylbenzyl alcohol position (Fig. 1). The permethrin-induced tail currents decayed rapidly, characteristic of type I-induced tail currents (Fig. 3D, 3E, Table 2). Interestingly, deletion of G1111 did not alter the BgNav1-1channel sensitivity to permethrin (Fig. 3F). To investigate whether the different responses of BgNav1-1G− to permethrin and deltamethrin are determined by the α-cyano group, we examined the responses of BgNav1-1 and BgNav1-1G− to three additional pyrethroids: bioresmethrin, cypermethrin and NRDC157. Bioresmethrin is another type I pyrethroid. Cypermethrin, a type II pyrethroid, differs structurally to permethrin only by the presence of the α-cyano group. NRDC157 is a deltamethrin analogue lacking the α-cyano group (Fig. 1). Similar to its response to deltamethrin, the BgNav1-1G− channel was significantly more resistant to cypermethrin than the BgNav1-1 channel (Fig. 4). However, the BgNav1-1G− channel remained as sensitive to bioresemethrin and NRDC157 as the BgNav1-1 channel (Fig. 4). NRDC157 also induced a typical type I tail current (data not shown), indicating that the α-cyano group is the determining factor of the decay of the tail current. These results indicate that G1111 is selectively involved in the response of sodium channels to type II pyrethroids and indicate that this selectivity is due to the direct or indirect interaction with the α-cyano group.

Figure 4.

Effects of the deletion of G1111 on channel sensitivity to cypermethrin, bioresmethrin, and NRDC157. Percentage modification by pyrethroids was determined as described in Fig. 3.

G1111 is located in the second intracellular linker connecting domains II and III and presumably provides a hinge for the adjacent sequences. We noticed that although the overall sequence of the intracellular linker is quite variable, the amino acid sequence around G1111 was highly conserved among insect sodium channels (Fig. 5A). Upstream of G1111 there are three conserved positively charged lysines (Ks) residues and two predicted α-strands in both BgNav variants. Downstream of G1111 is a conserved sequence containing five positively charged K residues also in both BgNav variants. To determine whether these conserved α-strands and K residues contribute to the response of sodium channels to type II pyrethroids, we made three recombinant BgNav1-1 channel proteins: BgNav1-1Δβ, which contains a deletion of a sequence (from L1097 to H1110) containing the two β-strands, BgNav1-13K→3Q, which contains substitutions of the three upstream Ks with three Qs, and BgNav1-15K→5Q, which contains substitutions of the five downstream Ks with five Qs. Deletion of the two β-strands and neutralization of the three Ks upstream of G1111 had no effect on the channel sensitivity to deltamethrin and permethrin (Fig. 5B). However, neutralization of the five downstream Ks (5K) to five Qs (5Q) reduced the channel sensitivity to deltamethrin (Fig. 5B), but not to permethrin (data not shown). Similarly, BgNav1-15K→5Q also exhibited reduced sensitivity to cypermethrin, but not to bioresmethrin and NRDC157 (Fig. 5C). The decay of the pyrethroid-induced tail currents was not affected by the neutralization of the five downstream Ks (Table 2).

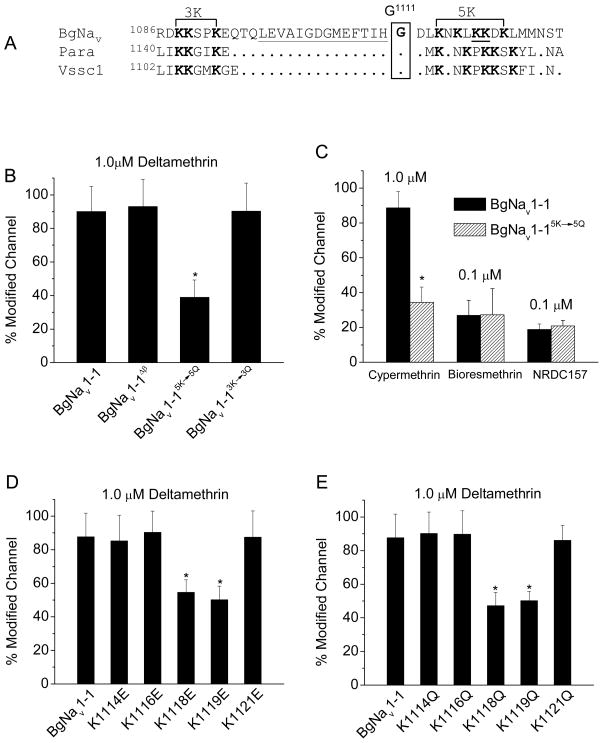

Figure 5.

Effects of charge neutralization and charge reversal of K residues or deletion of the putative β-strands on channel sensitivity to pyrethroids. A. Alignment of amino acid sequences flanking G1111 of BgNav, Drosophila Para and house fly Vssc1 sodium channels. A predicted β-strand upstream G1111 is underlined. Three K residues upstream and five K residues downstream G1111 are in bold. B. Histogram of the percentage of channel modification by deltamethrin of the recombinant channels BgNav1-1Δβ, BgNav1-15K→5Q and BgNav1-13K→3Q C. Histogram of percentage of channel modification by cypermethrin (1 μM), bioresmethrin (0.1 μM) and NRDC157 (0.1 μM) of BgNav1-15K→5Q. D. and E. Histogram of percentage of channel modification of five single K→Q (D) and five single K→E (E) substitution channels to deltamethrin (1 μM).

To determine which K in the five Ks is important for the action of deltamethrin, we made five charge-neutralization constructs in which the 5Ks were substituted individually with glutamate (Q) and also five charge-reversed constructs where the 5Ks were replaced individually by glutamic acid (E). We found that Q or E substitutions of two of the Ks, K1118 and K1119, reduced the channel sensitivity to deltamethrin (Fig. 5D and 5E).

Discussion

This study illustrates that pharmacologically distinct sodium channel variants generated by alternative splicing can be valuable resources in the understanding of the molecular mechanism of pyrethroid action. We found that exclusion of G1111 in the intracellular linker connecting domains II and III is caused by use of an alternative splicing acceptor (Fig. 2) and that this exclusion reduced BgNav channel sensitivity to type II pyrethroids, but interestingly, not to type I pyrethroids. Charge neutralization or charge reversal of two positively charged lysine residues downstream of G1111 also reduced the channel sensitivity to type II pyrethroids, but not type I pyrethroids. These results show that G1111 and the two downstream lysine residues confer specificity in BgNav channel interaction with type II pyrethroids.

Our knowledge of the interaction between pyrethroids and sodium channels at the molecular level has advanced significantly in the past decade thanks to intensive efforts to elucidate the molecular mechanism of insect resistance to pyrethroid insecticides. Amino acid mutations in various regions of insect sodium channels have been detected in pyrethroid-resistant insect populations and some of these mutations have been confirmed to reduce insect sodium channel sensitivity to pyrethroids in Xenopus oocytes (Soderlund 2005, Davies et al., 2007, Dong, 2007). In principle, the residues defined by these mutations could contribute to binding or post-binding action of pyrethroids on the sodium channel.

Because the extremely high lipophilicity of pyrethroids causes extremely high levels of nonspecific binding to membranes and filters in receptor binding assays, it has been impossible to use radiolabeled pyrethroids to assess pyrethroid binding to insect sodium channels (Rossignol, 1988; Pauron et al., 1989; Dong, 1993). Taking advantage of the competitive action of active and inactive isomers of permethrin (a type I pyrethroid) to the sodium channel, we previously conducted Schild analysis and provided evidence for the involvement of F1519 in IIIS6 and L993 in IIS6 in forming part of a type I pyrethroid-binding site on the cockroach sodium channel (Tan et al., 2005). We have shown that both F1519 and L993 are also required for the action of type II pyrethroids on the cockroach sodium channel, suggesting that these two residues most likely are also required for binding of type II pyrethroids to the cockroach sodium channel (Tan et al., 2005). Computer modeling of the pyrethroid binding site of the house fly sodium channel based on the crystal structures of the rat brain Kv1.2 and KvAP potassium channels implicated M918 in the IIS4-S5, T929I in IIS5, and F1538 (equivalent to F1519 in the cockroach sodium channel) in IIIS6 as part of a pyrethroid binding site (O’Reilly, et al., 2006; Davies et al., 2007). Recent site-directed mutagenesis of the IIS4-IIS5 linker and IIS5 revealed several additional residues in the IIS4-IIS5 linker and IIS5 involved in the action of pyrethroids (Usherwood et al., 2007). These results suggest that the pyrethroid-binding site is composed of amino acid residues donated from multiple transmembrane segments and intracellular linkers of the sodium channel. It is likely that in the activated (i.e., open) state, which is the preferred state for pyrethroid action, these residues may be located in the vicinity of each other, constituting a hydrophobic pocket to which pyrethroids bind.

Results from this study provides further insight into the molecular action of pyrethroids on the sodium channel, particularly with respect to the long-observed differences of action of type I and type II pyrethroids on the sodium channel. It has been well documented that tail currents induced by type II pyrethroids decay slowly, ranging from seconds to minutes, whereas tail currents induced by type I pyrethroids decay quickly in less than a second (Narahashi, 1988). The slower decay of tail current by type II pyrethroids results in enhanced membrane depolarization and conduction block, contributing to the greater potency of type II pyrethroids, compared with type I pyrethroids (Narahashi, 1988). Type II pyrethroids contain the α-cyano group, whereas type I pyethroids lack it. Interestingly, in this study we observed that a deltamethrin analogue lacking the α-cyano group behaved like type I pyrethroids and induced rapid decaying tail currents, further implicating a critical role of the α-cyano group in mediating the slow decay of type II pyrethroid induced tail currents. It is therefore possible that G1111 and two downstream lysine residues in the cockroach sodium channel are specifically involved in the molecular action of the α-cyano group.

There are several possible mechanisms by which G1111 and two downstream lysine residues might mediate the molecular action of the α-cyano group. First, the α-cyano group could provide a unique binding moiety, which would presumably produce more stable binding (or a different binding configuration) of type II pyrethroids (compared to type I pyrethroids) to the sodium channel. In this scenario, G1111 and two downstream lysine residues in the intracellular linker connecting domains II and III could directly participate in the binding of the α-cyano group or indirectly modulating the configuration of the pyrethorid-binding pocket to accommodate the α-cyano group. Second, the α-cyano group may not be involved in type II pyrethroid binding to the sodium channel, but it could mediate a post-binding interaction with a sodium channel sequence that reinforces the action of type II pyrethroids. G1111 and two downstream lysine residues could be involved in this post-binding unique action of the α-cyano group. Third, it is also possible that the α-cyano group is involved in both type II-specific binding and type II-specific post-binding modification of gating properties. We found that deletion of G1111 or neutralization of the downstream Ks did not alter the rate of decay of type II-induced tail currents (i.e., without converting the type II-tail current to a type I-tail current). However, deletion of G1111 or neutralization of the downstream Ks significantly reduced the effectiveness of type II pyrethroids to induce the tail current. Thus, our results are most compatible with the first mechanism and suggest that G1111 and the downstream Ks are crucial for the unique binding of type II pyrethroids to the sodium channel. G1111 may function as a hinge to position the downstream K residues close to the α-cyano group, thereby stabilizing the binding of type II pyrethroids. Because type I pyrethroids do not have the α-cyano group, their binding and action do not need G1111 and the two downstream K residues. At this point, however, we cannot rule out the possibility that G1111 and the downstream two K residues influence type II pyrethroid binding from a distance, via an allosteric mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kris Silver for critical review of this manuscript. The work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (GM057440) and National Science Foundation (IBN0224877) to K. D. Rothamsted Research Ltd receives grant-aided support from the Biotechnological and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) of the United Kingdom.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Davies TGE, Field LM, Usherwood PNR, Williamson MS. DDT, pyrethrins, pyrethroids and insect sodium channels. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:151–162. doi: 10.1080/15216540701352042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong K. PhD thesis. Cornell University; Ithaca, New York: 1993. Molecular mechanism of knockdown (kdr)-type resistance to pyrethroid insecticiedes in the German cockroach (Blattella germanica L.) [Google Scholar]

- Dong K, Scott JG. Linkage of kdr-type resistance and the para-homologous sodium-channel gene in German cockroaches (Blattella germanica) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;24:647–654. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong K. Insect sodium channels and insecticide resistance. Invert Neurosci. 2007;7:17–30. doi: 10.1007/s10158-006-0036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M. Synthetic pyrethroids. In: Elliott M, editor. Synthetic pyrethroids. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1977. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Feng G, Deak P, Chopra M, Hall LM. Cloning and functional analysis of tipE: a novel membrane protein that enhances Drosophila para sodium channel function. Cell. 1995;82:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammon DW, Brown MA, Casida JE. Two classes of pyrethroid action in the cockroach. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1981;15:181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Song W, Dong K. Persistent tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium current resulting from U-to-C RNA editing of an insect sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11862–11867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307695101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund AE, Narahashi T. Kinetics of sodium channel modification by the insecticide tetramethrin in squid axon membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;219:463–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T. Molecular and cellular approaches to neurotoxicology: past, present and future. In: Lunt GG, editor. Neurotox ‘88: molecular basis of drug and pesticide action. Elsevier; New York: 1988. pp. 563–582. [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T. Neuronal ion channels as the target sites of insecticides. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;79:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1996.tb00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly AO, Khambay BP, Williamson MS, Field LM, Wallace BA, Davies TG. Modeling insecticide-binding sites in the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biochem J. 2006;396:255–263. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauron D, Barhanin J, Amichot M, Pralavorio M, Berge JB, Lazdunski M. Pyrethroid receptor in the insect Na+channel: alteration of its properties in pyrethroid resistant flies. Biochemistry. 1989;28:1673–1677. [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol DP. Reduction in number of nerve membrane sodium channels in pyrethroid resistant house flies. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1988;32:146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund D. Sodium channels. In: Gilbert LI, Latrou K, Gill SS, editors. Comprehensice Insect Science. Vol.-5 pharmacology. Elsevier B.V; 2005. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund DM, Knipple DC. The molecular biology of knockdown resistance to pyrethroid insecticides. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:563–577. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Liu Z, Tan J, Nomura Y, Dong K. RNA editing generates tissue specific sodium channels with distinct gating properties. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32554–32561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402392200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Liu Z, Tsai TD, Valles SM, Goldin AL, Dong K. Novel sodium channel gene mutations in Blattella germanica reduce the sensitivity of expressed channels to deltamethrin. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002a;32:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00122-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Liu Z, Wang R, Huang ZY, Chen AC, Gurevitz M, Dong K. Identification of amino acid residues in the insect dodium channel critical for pyrethroid binding. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:513–522. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Liu Z, Nomura Y, Goldin AL, Dong K. Alternative splicing of an insect sodium channel gene generates pharmacologically distinct sodium channels. J Neurosci. 2002b;22:5300–5309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05300.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi H, Narahashi T. Differential mechanism of action of the pyrethroid tetramethrin on tetrodotoxin- sensitive and tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:595–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usherwood PNR, Davies TGE, Mellor IR, O’Reilly AO, Peng F, Vais H, Khambay BPS, Field LM, Williamson MS. Mutations in DIIS5 and the DIIS4-S5 linker of Drosophila melanogaster sodium channel define binding domains for pyrethroids and DDT. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5485–5492. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vais H, Williamson MS, Goodson SJ, Devonshire AL, Warmke JW, Usherwood PNR, Cohen CJ. Activation of Drosophila sodium channels promotes modification by deltamethrin: reductions in affinity caused by knock-down resistance mutations. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:305–318. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijverberg HP, van der Zalm JM, van der Bercken J. Similar mode of action of pyrethroids and DDT on sodium channels gating in myelinated nerves. Nature. 1982;295:601–603. doi: 10.1038/295601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]