Abstract

In 2006, the Federal Collaboration on Health Disparities Research (FCHDR) identified the built environment as a priority for eliminating health disparities, and charged the Built Environment Workgroup with identifying ways to eliminate health disparities and improve health outcomes.

Despite extensive research and the development of a new conceptual health factors framework, gaps in knowledge exist in areas such as disproportionate environmental and community hazards, individual and cumulative risks, and other factors.

The FCHDR provides the structure and opportunity to mobilize and partner with built environment stakeholders, federal partners, and interest groups to develop tools, practices, and policies for translating and disseminating the best available science to reduce health disparities.

IN 2006, THE FEDERAL COLlaboration on Health Disparities Research (FCHDR) convened leading scientists and officials across 14 federal departments and identified the built environment as one of the top priorities for eliminating health disparities through collaborative action. An outstanding opportunity currently exists to integrate health care into community development, since “two thirds of all development … needed in 2050 has yet to be built or redeveloped,”1 and massive investments in infrastructure and green building investments are now under way.2 Public health and environmental scientists are increasingly focused on the interdependent relationship between the built environment and health disparities. The US Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA's) Office of Sustainable Communities, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Department of Transportation (DOT), and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have collaborated to help eliminate disparities in the built environment by promoting environmentally friendly developments—coined “smart growth”—that emphasize housing and transportation choices, as well as public and private investments that promote physical activity; cleaner, safer communities; and access to health care and healthy foods. Preliminary projections show substantial health care savings through improvements in the built environment. However, a better understanding of the social and environmental health factors that disproportionately contribute to poor health outcomes for disadvantaged and vulnerable communities is needed.

In this essay, we (1) highlight the need for research, policies, and tools to help eliminate environmental factors that disproportionately contribute to disparities among disadvantaged and vulnerable communities; (2) describe the association between the built environment and disparities in health outcomes; and (3) provide recommendations for policy research dissemination.

BUILT ENVIRONMENT WORKGROUP

The Built Environment Workgroup of the FCHDR is charged with promoting research and collaboration among governments, nongovernment organizations, and the private sector to examine how conditions related to socioeconomic factors may affect the health of disadvantaged and vulnerable populations.3 The workgroup is also responsible for identifying research gaps related to how the built environment (commercial, industrial, residential, and infrastructure development) affects the environment, safety, disparities in health outcomes, and behaviors of disadvantaged populations, with the expectation of accelerating the development of new evidence-based interventions.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF BUILT ENVIRONMENT AND RISK FACTORS

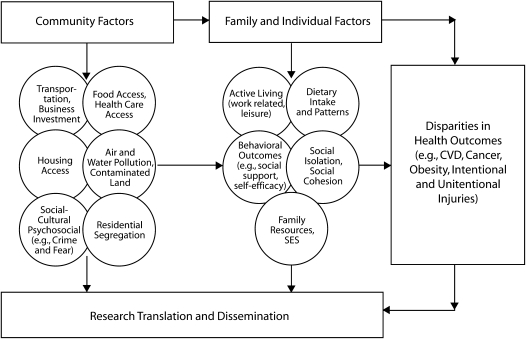

The FCHDR's conceptual framework of the built environment and disparities in health (Figure 1) shows the linkages between community factors and family and individual factors in the built environment. Federal, state, and local governments, as well as urban planners, are considering public health and health issues as they create new neighborhoods and revitalize others.4 They seek to address challenges and opportunities in disadvantaged and vulnerable communities to overcome racial and ethnic health disparities.4 Research shows that there is a general connection between features of the built environment and an increase in chronic health problems, especially those tied to obesity, lack of exercise, poor nutrition, and pollutants. FCHDR's conceptual framework highlights some specific opportunities for undertaking such research.4

FIGURE 1.

The Federal Collaboration on Health Disparities Research's conceptual framework of the built environment and disparities in health.

Factors associated with the built environment at the community, family, and individual levels are linked to health disparities and contribute to the development of chronic illnesses and other conditions.5 The built environment can have profound, directly measurable effects on both physical and mental health outcomes among disadvantaged and vulnerable communities.6 However, the question of how and why the environment influences health outcomes remains largely unexplored.7

Community Factors

Manmade structures and metropolitan planning have an impact on health.8 Seven community factors of the built environment are important in improving health outcomes for disadvantaged and vulnerable communities: (1) transportation and business investments; (2) access to food; (3) access to health care; (4) access to housing; (5) air and water quality, as well as uncontaminated land; (6) sociocultural, psychosocial (e.g., reduced crime and fear), and socioeconomic factors; and (7) reduced residential segregation.

Transportation and business investments.

During the past several years, much research has related transportation and the built environment to public health outcomes. The main feature of these findings is the association between current transportation networks, their surrounding built environment, and the increasing incidence of obesity.9 Previous land use and transportation literature suggests that smart growth—characterized by higher-density, mixed commercial and residential land uses—can reduce dependency on automobiles and resulting pollution by decreasing travel time to common destinations.

Pedestrian safety and access to transportation are important to disadvantaged and disabled populations. As the Funders' Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities observes, “Transportation systems designed for cars instead of pedestrians are unfriendly to pedestrians and doubly unfriendly to those with special transportation needs.”10 Environmental conditions that stem from automobile-oriented development can increase the incidence of respiratory impairment, amputations, and disabilities related to diabetes. Smart growth approaches—including increased transportation choices and a mix of residential and commercial land uses—and reinvestment in older communities can reduce disadvantaged and disabled people's social isolation and lack of access to commerce.

In addition, demand is growing for business investments to support equitable development. Business development can facilitate infrastructure enhancements aimed at continuously improving the level and quality of services.11

Food access.

Research has documented that many disadvantaged and vulnerable communities have few supermarkets with fresh foods, which contributes to disparities in health.12 Matson-Koffman et al.12 reported that site-specific interventions were most effective at promoting physical activity and access to good nutrition. They further reported that the availability of nutritious foods, as well as point-of-purchase strategies, had a strong influence on behavior change. These findings suggest a link between access to and availability of food and health risks.

Health care access.

Although few reports examine the association between the built environment and access to health care, research suggests that for some vulnerable and disabled populations, unavailability of low-cost care providers, poor geographic accessibility, inadequate transportation, and lack of providers' language or cultural competency contribute to lack of health care access.13

Housing access.

For communities of low socioeconomic status, inequities in construction and maintenance of low-income housing have resulted in insufficient housing, poor quality housing, overcrowding, and health problems.14 Poor and inadequate housing conditions can lead to anxiety, depression, attention deficit disorder, substance abuse, aggressive behavior, asthma, heart disease, and obesity, as well as exposure to lead, pests, air pollution, contaminants, and greater social risks.14

Air and Water Pollution and Contaminated Land.

Communities of color are disproportionately affected by poor air quality,15 brownfield sites or abandoned properties that may contain hazardous wastes,16 and industrial releases of pollutants.17 In addition, the rapid growth of wealthier, low-density developments in outlying areas increases vehicular traffic, air pollutants, and ozone in urban areas, increasing the frequency and intensity of asthma attacks.18 Suburban development also increases the release of effluent from septic systems into groundwater, destroys wetlands and vegetation, and increases impervious surfaces and polluted storm water that contribute to food source contamination (e.g., mercury in fish),18,19 affecting minority subsistence fishermen.15 Inequitable industrial risks are indicated by one study that found that “host neighborhoods with commercial hazardous waste facilities are 56% people of color whereas nonhost areas are 30% people of color.”20 Public involvement plus planning tools can address public health concerns of disparately affected communities.21

Sociocultural and psychosocial factors.

Perceived and real safety issues hinder active lifestyles. People are more reluctant to walk, bicycle, jog, or play in neighborhoods that they feel are not safe, leading to both physical inactivity and decreased likelihood of obtaining healthy foods at retail stores. A national survey found that twice as many low-income respondents as moderate-income respondents worried about safety in their neighborhoods.22 However, it is not clear to what extent crime or fear is associated with lower levels of physical activity, especially among minority women, young people, and seniors.22

Structural factors help determine the boundaries of health promotion and the state of stressors and resources in a community. When factors such as pollution overwhelm neighborhood resources, levels of community stress increase, which in turn may lead to individual-level stress that further exacerbates illness caused by the environmental pollution.23

Residential segregation.

Low-income and minority populations tend to be isolated from affluent neighborhoods, job centers, and business development, and they are primarily located near noxious industrial facilities or freeways. These communities may consist of decaying commercial corridors characterized by limited access to employment opportunities and to sources of quality goods and services, such as supermarkets and banks,4 but saturated with liquor stores, check-cashing stores, and dilapidated public buildings and infrastructures, including schools, roads, and parks. These conditions contribute to health disparities in a number of ways (e.g., crime, injury, depression, addiction).4 Exclusionary zoning in the suburbs that mandates expensive, large-lot, single-family homes leads to segregation and concentrated poverty, whereas efforts to rebuild declining communities can displace long-time residents.22

Family and Individual Factors

Family and individual factors of the FCHDR's conceptual framework include active living, dietary intake and patterns, behavior outcomes, social isolation and cohesion, and family resources and socioeconomic status (SES). The locations of businesses and organizations, modes of travel, and housing can influence physical activity or create environmental risks for families or individuals.22

Active living.

When neighborhoods have nearby shopping areas, a pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly infrastructure, and accessible public transit, children and their families are encouraged to walk and use bicycles.22 Residents who live in such communities tend to be more physically active.24

Moderate and vigorous physical activity is a protective factor against a variety of chronic conditions, such as musculoskeletal abnormalities, obesity, and diabetes.24 Kaczynski and Henderson reviewed 50 articles on the quantitative relationships between parks and recreational settings and physical activity, and concluded that low-income and vulnerable communities had a limited number of parks and recreation facilities (e.g., playgrounds, sport courts, walking paths).25 Shores and West found that the quality of such facilities was often below the standards seen in other communities.26

In a recent supplement of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, many authors addressed the issue of health disparities in neighborhoods. Disordered neighborhood environments reportedly discouraged children and parents from using neighborhood parks.27,28 Poor pedestrian accommodation was found in Hispanic neighborhoods,29 and living in areas with higher land use mix was associated with lower body mass index across gender and ethnicity.30 These findings of disparities in the built environment highlight how community and SES factors can interact to influence physical inactivity and risk of cardiovascular diseases (see the box on this page).

Strategies for Integrating Health, Active Living, and Improved Environmental Quality Into Equitable Development Options: The Federal Collaboration on Health Disparities Research Conceptual Framework

| Strategy | Description |

| Smart growth | |

| Dalbey31 | Development of mixed land use, compact building design, walkable neighborhoods, active and attractive communities, preservation of open space and critical environmental areas, availability of a variety of transportation choices, and community and stakeholder collaboration should be integrated in development decisions. |

| EPA32 | Moving 5%–10% of jobs to infill redevelopment of existing communities can reduce the jobs to housing imbalances caused by metropolitan sprawl and would allow for compact transit oriented developments that would result in a reduction in automobile use and a 3%–8% reduction in greenhouse gasses and pollution. |

| Transit oriented developments could reduce vehicle-miles traveled by up to 38% and yield much higher benefits at the site level. | |

| Public–private partnerships33 | 4 critical components for improvement of school yards: |

| 1. partnership between school and community, | |

| 2. multiuse facilities in the school yard that include outdoor education considerations in the design, | |

| 3. upkeep and maintenance responsibilities for the school yards that is a joint community and city effort, and | |

| 4. funding for school yards based on a public-private partnership model. | |

| Advocacy34 | 3 strategies for advocating bicycling paths within the city of Arlington VA are: |

| 1. political advocacy to select professional managers who see bikeways as crucial to the overall transportation system (a government-citizen relationship through an advisory panel is useful for addressing the need for bikeways), | |

| 2. a gradual implementation strategy that builds small pieces of standards at a time (components of a system into place for later upgrading), and | |

| 3. taking advantage of opportunities or natural experiments in sometimes negative circumstances (e.g.,construction of I-66 was an opportunity for county leaders to construct parallel bicycle paths). | |

| Regulations35,36 | Local-, town-, and city-level tools exist for affordable housing, environment, pedestrian overlay zones, cycling and mixed use developments, vibrant walkable commercial districts, and citizen involvement plus commentary. These tools help combat urban sprawl, protect farmland, promote affordable housing, and encourage redevelopment. |

| Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design37 | This handbook and this research on how to apply problem solving, community planning, and safety and security assessments include approaches for hot spots, lighting, traffic calming barriers, and target hardening. These methods encompass maintenance, ordinances and laws, and other approaches to crime prevention. |

| Public investment8 | Vacant property improvements, rehabilitation of housing, greening of abandoned lots, and business improvement districts reduced crime and improved housing values in surrounding communities. |

Dietary intake and patterns.

Access to healthy, wholesome foods is often limited for those residing in rural, disadvantaged, and vulnerable communities.39 Several studies have demonstrated that low-income neighborhoods have far fewer supermarkets than do middle-income neighborhoods and that African American and Hispanic neighborhoods are less likely than are White neighborhoods to have these stores.40 In some low-income neighborhoods, however, retailers feature affordable produce and ingredients for the traditional ethnic diets of neighborhood residents.22

Behavioral outcomes.

The built environment can be a particularly strong behavioral determinant for behaviors such as physical activity that are directly shaped through environmental constraints and supports.41,42 Experts now agree that the built environment must be considered in an effort to understand or reduce rates of obesity and adverse health conditions,43 to encourage walking and cycling, and to create pedestrian-friendly places.7

Whether we walk to work or school, eat frequently at fast food restaurants, or take our children to parks depends in part on how our neighborhoods are designed and built.7,44 Social support, including personal interactions and modeling neighbors' behavior, provides the context for physical activity, eating healthy foods, drinking plenty of water, and getting regular medical checkups.8 Changes to the built environment should be accompanied by person-oriented interventions aimed at improving individual attitudes, self-efficacy, and perception.8

Social isolation and social cohesion.

Studies have shown that various aspects of the built environment can trigger social isolation.6 These aspects include a lack of sidewalks, bike paths, and recreational areas; threat of crime; poor housing; limited access to healthy food; and income segregation (i.e., concentrating the poor in discrete areas of the city). Studies have also shown that negative aspects of the built environment tend to interact with and magnify health disparities, compounding already distressing conditions such as social isolation.6

Social cohesion—how much residents know and care about their neighbors and participate in community activities—has declined over the previous decades.45 Transportation and land use planning can affect community cohesion by influencing the location of activities and the quality of sidewalks, local parks, and public transportation.46

Family resources and socioeconomic status.

There is a clear association between socioeconomic position and disease.18 Studies have shown that individuals of higher social standing tend to have better health than do those of lower standing.47 Even after socioeconomic characteristics are accounted for, persons living in poor neighborhoods tend to have worse health outcomes.21

DISPARITIES IN HEALTH OUTCOMES

Chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, obesity, asthma, injuries, and depression, as well as health hazards from environmental toxins and infectious agents, can be moderated by the design and characteristics of the built environment.18 Exclusionary housing, finance, and zoning policies48,49 have relegated disadvantaged and vulnerable populations to declining, less healthy, and dangerous inner-city communities21,49 that have high rates of crime, unemployment, despair, and abandoned buildings.10,21 Unequal and sprawling metropolitan growth harms environmental quality while increasing health risks and promoting decentralized growth, automobile dependency, and polluted water runoff.49 Neighborhoods have become less walkable and cohesive as zoning has separated residential and commercial areas.21 Inner cities and older suburbs lack targeted, well-planned business and civic investments as well as adequate policing and recreation to promote healthier, walkable communities (see box on page 590).

Equitable Investment Strategies, Health Assessments, and Active Living That Can Yield Substantial Benefits

| Equitable Investments in Active Living | Benefits |

| Local tools: HIAs, smart growth assessments, and policies for regional equity | |

| Mitigate risks of proposed transportation projects with HIAs to improve air quality and increase social benefits. | Increased walking, cycling, and transit use decreases air quality concerns and increases active lifestyles. |

| Neighborhood stabilization and vacant property rehabilitation and brownfield site reuse and vacant properties campaign of the Smart Growth America and Local Initiatives Support Corporation. | Decreased asthma risks from PM. |

| Decreased headaches, heart disease, cardiopulmonary disease, bronchitis from carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, and VOCs or smog, and decreased cancer linked to hazardous air pollutants including VOCs. | |

| Decreased onset and severity of chronic illness, disabilities, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes through active living investments. | |

| Reduce racial and social isolation, and increase pedestrian, elderly, and disabled access and accommodation. | Reduced violent crime and pedestrian injuries. |

| Elderly and disabled can improve health via improved accessibility. | |

| CPTD to positively influence human behavior, focusing on safety and places that are risky to commit crime.37 | Decreased risk of crime and violent injury via careful land use design. |

| Induce more active living and walking with community investments to improve safety, increase investments in transit and vacant property enhancements (to spur more pedestrian travel), and add eyes on the street via added investment. | $1.5 billion to $6.1 billion/y potential savings from CPTD and cancer based on decreasing automobile dependency and sedentary living for disadvantaged populations (cumulative 30-y total = $57 billion to $228 billion NPV).ab |

| $128 million to $512 million/y annual savings from reduced asthma among urban minorities (cumulative 30-y total = $18.8 billion to $4.7 billion)ab | Improve air quality and decrease smog by reducing automobile dependency and increasing transportation choices. |

| Federal, state, and regional tools: policies for reinvestment | |

| Fix it first, priority funding areas and tax increment financing to aid reinvestment. | Strengthen older, poorer communitites to provide context for attractive, walkable communities. |

| Environmental Justice Executive Order 12898, Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the American Disabilities Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Community Reinvestment Act, and fair housing laws. | Reduced health risks associated with low socioeconomic status and inequitable location of contaminated or polluting facilities or properties. |

| Transportation planning. | Improve air quality. |

| Open space and environmental preservation to promote reinvestment. | Added savings from parks and trails: $1.00 spent on trails yields $2.94 dollars in benefits from trail users.52 |

| Business support for improved jobs-to-housing balance that increases efficiency and decreases sick days. | |

Note. CPTD = Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design; HIA = health impact assessment; NPV = net present value; VOC = volatile organic compound.

Estimates reflect potential benefits associated with built environment improvements and are based on a model to estimate the scale of benefits by Built Environment Workgroup Chair for the Federal Collaboration on Health Disparities Research (D.J.H.). Public education and recreation associated with active living may improve outcomes as well. These benefits are a subset of total benefits and disease outcomes averted through active living and cleaner transportation modes. Asthma estimates based on benefits derived from a case study of automobile travel vs bus travel emissions50 and baseline estimates of asthma costs.51 Conservative safety factors reduced working estimates resulting in conservative final estimates of one tenth to four tenths of final estimates. Asthma used a 1.28 risk escalation factor along with safety factors.

Figures based on weighted public and private discount rates based on gross domestic product public–private split.

RESEARCH TRANSLATION AND DISSEMINATION

Many gaps exist in health disparities research. The goal of the FCHDR is to provide a structure for federal agencies, stakeholders, and partners to work collaboratively and to help eliminate health disparities related to the built environment.

Federal and community partners can help build strong evidence-based research targeting the built environment to improve health outcomes among low-income and vulnerable populations. Research areas that warrant investigation include rebuilding public housing and disadvantaged communities into greener, healthier, communities; designing communities and green buildings to eliminate specific indicators of population, community, and environmental health disparities; incorporating smart growth and crime prevention through design; leveraging brownfield sites and vacant property improvements; exploring medical insurance losses and expenditures among vulnerable populations; examining mobile source pollutants; and investigating housing and community risks related to crime, safety, vacant properties, and limited business investment.

Cross-sectional, longitudinal, and intervention studies53 are needed to address the built environment and disparities in health outcomes. Several studies are being developed to address these issues, such as the National Institutes of Health Genes, Environment, and Health Initiative; the Irvine-Minnesota inventory on built environment; and the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design and Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND).53,54 However, additional research is needed to link community design and green spaces with specific indicators of health risk for disadvantaged or low-income communities. Federal and community partners can work together to translate and disseminate research through peer-reviewed journals, Web-based communications, and marketing.

SUCCESSFUL POLICIES, TOOLS, AND PRACTICES

A review of the literature reveals several successful policies, tools, and practices that have been developed to improve health disparities in the built environment. Metropolitan planning organizations have approved plans for up to $244 billion in transportation funds that support investments in transportation choices to improve air quality while reducing mobile source pollutions.49,55 The Livable Communities Initiative in the Atlanta region won the EPA's National Smart Growth Award by leveraging transportation funds for improving air quality with private-sector and government sources to transform declining towns and villages into thriving walkable, transit-oriented communities.56 The Brownfields Cleanup and Redevelopment Program and the Leaking and Underground Storage Tank Programs are useful tools that can transform abandoned and contaminated sites into community assets.57,58 The creation of compact, pedestrian-friendly communities with good public transportation has led to improved air quality.10 Streetscape improvements and better traffic control have reduced automobile injuries.10

Major improvements are being made in many distressed communities through the early and meaningful community involvement of vulnerable populations. The Highpoint Development in King County, Washington, and the New Columbia Development in Portland, Oregon, have transformed dangerous isolated public housing into vibrant, mixed-use, environmentally friendly developments that satisfy demands for affordable housing. Egleston Crossing, a low-income, mixed-use development in Boston's Roxbury community, cleaned up decrepit brownfield site properties and implemented green building designs near public transit, which spurred business growth, increased pedestrian traffic, and created an inviting neighborhood.56

RECOMMENDATIONS TO IMPROVE HEALTH OUTCOMES

The FCHDR Built Environment Workgroup suggested working with its partners on strategies for improving health disparities with respect to the built environment. Some of those strategies are:

Establish community investments by incorporating a health, cumulative-risk, and active-living framework into urban planning, which is essential for reducing health disparities for vulnerable populations. Federal, state, and local government officials can partner with community organizations to find mutual incentives to promote healthier communities (see box on page 590).

Support energy-efficient, nontoxic building practices and developments for disadvantaged communities by using the LEED-ND54 combined with an equitable smart growth agenda. The FCHDR can promote strategies to efficiently integrate health and environmental concerns to benefit growing minority populations (see box on this page).

Reduce health disparities in housing, urban redevelopment, and home energy subsidies by using Health Impact Assessments (HIAs) as an evaluation mechanism.60 HIAs can lead to better decision-making through standardized models, protocols and checklists, public and stakeholder participation, and quantitative analytic approaches. HIAs, which draw from epidemiology, risk analysis, community-based health promotion, are similar to environmental impact analyses but less costly and more broadly applicable.61 Improving HIA capacities and creating regular mechanisms for collaboration with local, state, and federal entities and investors are needed to fulfill the promise of HIAs in reducing disparities.

Use new community health center investments to anchor grocery stores, shops, parks, recreation for disadvantaged neighborhoods and ensure public transportation and sidewalk access.

Rehabilitate vacant properties, improve landscaping, and promote trash cleanups through targeted business investments to improve depressed market values and reduce violence and crime.62 Community-benefit agreements and community involvement can help prevent displacement of disadvantaged groups.

Link built environment intervention strategies with tangible health, productivity, and medical care savings. The Built Environment Workgroup economist (D. J. H.) completed a national health benefits model that made preliminary projections of the scale of savings from smart growth or active living scenarios for minority subpopulations for cardiovascular disease, cancer, and asthma. According to that model, the cumulative 30-year benefits were up to $228 billion over 30 years (see box on page 591). Adding type II diabetes mellitus, mental health impacts, lead poisoning, childhood development, safety, and violent crime to the model would greatly expand the magnitude of these benefits.

Encourage the use of community-based participatory research for FCHDR built environment research projects. Community-based participatory research can foster a capacity-building system that encourages creative thought, communication, social learning, and community involvement among stakeholders.63

Demographics and Land Use Trends and Potential Solutions for Efficiently Building Cleaner, Healthier Communities

| Trends |

| Current trends |

| Sprawl spawns disinvestment, lowers tax base, and increases unemployment, crime, and health disparities that inhibit healthy, active lifestyles. |

| Subsidies favor new investment at expense of repair of older areas. |

| Minorities concentrate in low air quality areas resulting from auto-dependent regional growth. |

| Estimated demographic growth by 2050a |

| US population increases by 50% (131 million).a |

| Minority population increases by 90%.a |

| Residential growth increases by 42% (52 million units).b |

| 37 million homes rebuilt or replaced.b |

| Nondefense construction: expenditure = $1 trillion/ya |

| Solutions |

| Foster reinvestment, compact growth, and walkable communities. |

| Save billions of dollars in infrastructure, utilities, and services and improve jobs-to-housing balance. |

| Make older communities healthier and more competitive via green building and rehabilitation. |

| Save open spaces, lower automobile emissions, and decrease polluted water run-off from sprawl. |

| Move 5%–10% of jobs in region to existing areas to reduce ozone and greenhouse gasses by 3%–8% and vehicle-miles traveled by 2%–5% while increasing opportunities for poorer communities.32 |

| At the site level, urban transit–oriented and brownfield site redevelopment and infill can reduce vehicle-miles traveled by 38% with reductions in pollution and greenhouse gasses.1,32 |

| Reinvestment can clean up abandoned industrial sites and toxic waste risks that are prevalent in disadvantaged communities. |

| Improve vacant properties and business investments to discourage crime and increase walking. |

Establishing a capacity-building partnership63 between the FCHDR and its stakeholders can serve as a conduit for experts on best practices, health needs, and policies. It may also ensure that land use and transportation planning research needs specific to the unique characteristics of vulnerable and disabled populations are fulfilled.

CONCLUSIONS

The FCHDR can identify a myriad of built environment and metropolitan planning concerns that promise to reduce disparities and yield substantial health benefits. The FCHDR can be a conduit for diverse partnerships with federal, state, and local governments, communities, nongovernment organizations, health officials, and non–health-related stakeholders to eliminate disparities on the ground.

FCHDR, health reform, and the interagency Partnership for Sustainable Communities present an opportunity to reexamine polices across sectors for healthier, more walkable communities. A support system of capacity building and new partnerships across the federal government can influence the level and type of health-sustaining investments in communities to realize future health gains. The momentum from an expanding demographic, green building, economic stimulus, and the HUD-DOT-EPA Partnership for Sustainable Communities presents an opportunity to integrate health into new community investments. While the FCHDR provides a key resource to disseminate needed research and strategies to eliminate health disparities, evidence-based policies and systems approaches are also needed. The FCHDR can work with stakeholders and partners to develop evidenced-based tools and inform discourse, policy, and practices to reach that goal.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the FCHDR Built Environment Workgroup.

References

- 1.Ewing R, Bartholomew K, Winkleman S, Walters JC. Growing Cooler: The Evidence of Urban Development and Climate Change. Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute; October 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Dept of Commerce May construction at $1074 billion annual rate, July 1, 2008. Available at: http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2010/tables/10s0928.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2010

- 3.Rashid JR, Spengler RF, Wagner RM, et al. Eliminating health disparities through transdisciplinary research, cross-agency collaboration, and public participation. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):1955–1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee M, Rubin V. The Impact of the Built Environment on Community Health: The State of Current Practice and Next Steps for a Growing Movement. Los Angeles, CA: PolicyLink; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 5.The DRA Project (Accelerating Disparity Reducing Advances). Using Healthy Eating and Active Living Initiatives to Reduce Health Disparities. Bethesda, MD: Institute for Alternative Futures; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hood E. Dwelling disparities: how poor housing leads to poor health. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(5):113–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saarloos D, Kim J, Timmermans H. The built environment and health: introducing individual space-time behavior. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(6):1724–1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prevention Institute The built environment and health: 11 profiles of neighborhood transformation. Available at: http://www.preventioninstitute.org/builtenv.html. Accessed September 22, 2009

- 9.Ross C.L. Can transportation design promote public health outcomes? A critical review of the literature. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Public health Association; November 9, 2004; Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funders' Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities Health and smart growth: building health and promoting active communities. Available at: http://www.activeliving.org/files/health_and_smart_growth.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2010

- 11.Howes R, Robinson H. Infrastructure for the Built Environment: Global Procurement Strategies. Burlington, MA: Butterworth Heinemann; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matson-Koffman DM, Brownstein JN, Greany ML. Site-specific literature review of policy and environmental interventions that promote physical activity and nutrition for cardiovascular health: what works? Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(3):1671–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi L, Stevens GD, Politzer RM. Access to care for US health center patients and patients nationally: how do the most vulnerable populations fare? Med Care. 2007;45(3):206–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan S, O'Fallon LR, Dearry A. Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1446–1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reducing Risks for All Communities, Volume 2: Supporting Document. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency; June 1992. Publication EPA 230-R-92-008a [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Environmental Protection Agency Environmental justice, urban revitalization and brownfields: the search for authentic signs of hope. December 1996. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/compliance/resources/publications/ej/nejac/public-dialogue-brownfields-1296.pdf. Accessed December 24, 2009

- 17.Prelin SA, Setzer W, Creason J, Sexton K. The distribution of industrial air emissions by income and race in the United States: an approach using toxic release inventory. Environ Sci Technol. 1995;29(1):69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson RJ, Kochtitzky C. Creating a healthy environment: the impact of the built environment on public health. Available at http://www.sprawlwatch.org/health.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2011

- 19.Chesapeake Bay Program Chemical contaminants. Available at: http://www.chesapeakebay.net/chemicalcontaminants.aspx?menuitem=14692. Accessed January 1, 2009

- 20.Bullard R, Mohai P, Saha R, Wright B. Toxic waste and race at twenty: 1987–2007. March 1987. Available at: http://www.ejrc.cau.edu/TWART%20Final.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2010

- 21.Rutledge P, Barnes AJ, Benavides T, et al. Addressing Community Concerns: How Environmental Justice Relates to Land Use and Planning and Zoning. Washington, DC: National Academy of Public Administration; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee V, Mikkelson L, Lee V, Srikantharajah J, Cohen L. Healthy eating active living convergence partnership: working together to create healthy people in healthy places. Available at: http://www.convergencepartnership.org/atf/cf/%7B245A9B44-6DED-4ABD-A392-AE583809E350%7D/CP_Built%20Environment_printed.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2009

- 23.Gee GC, Payne-Sturges DC. Environmental health disparities: a framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(17):1645–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Floyd MF, Crespo CJ, Sallis JF. Active living research in diverse and disadvantaged communities: stimulating dialogue and policy solutions. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(4):271–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaczynski AT, Henderson KA. Parks and recreation settings and active living: a review of associations with physical activity function and intensity. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5(4):619–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shores KA, West ST. The relationship between built park environments and physical activity in four park locations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(3):e9–e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pratt CA. Findings from the 2007 active living research conference: implications for future research. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(4):366–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miles R. Neighborhood disorder, perceived safety and readiness to encourage use of local playgrounds. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(4):275–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, Lee C. Disparities in walkability and safety of the environment around elementary schools. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(4):282–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frank L, Andresen M, Schmid T. Obesity relationships with community design, physical activity and time spent in cars. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):87–96 Available at: http://www.act-trans.ubc.ca/documents/ajpm-aug04.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalbey M. Implementing smart growth strategies in rural America: development patterns that support public health goals. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(3):238–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monitoring the Air Quality and Transportation Impacts of Infill Development. EPA 231-R-07-001. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency; 2007. Available at http://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/pdf/transp_impacts_infill.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez R, Campbell R, Jennings J. The Boston schoolyard initiative: a public-private partnership for rebuilding urban play spaces. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2008;33(3):617–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanson R, Young G. Active living and biking: tracing the evolution of a biking system in Arlington, Virginia. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2008 Jun;33(3):387–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Planning Association Model Land-Development Regulations. Available at: http://www.planning.org/research/smartgrowth. Accessed January 27, 2011

- 36.American Planning Association Growing Smart Legislative Guidebook. Available at: https://www.planning.org/growingsmart/guidebook/print. Accessed January 27, 2011

- 37.Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design. CPTED Handbook. Available at: http://www.CPTEDhandbook.com. Accessed January 27, 2011.

- 38.Wachter SM, Gillen KC. Public Investment Strategies: How They Matter for Neighborhoods in Philadelphia. Philadelphia, PA: Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania; October 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rutt CD, Coleman KJ. Examining the relationships among built environment, physical activity and body mass index in El Paso, TX. Prev Med. 2005;40(6):831–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents' diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1761–1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owen N, Humpel N, Leslie E, Bauman A, Sallis J. Understanding environmental influences on walking: review and research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bandur A. Social Foundation of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sallis JF, Glanz K. The role of built environments in physical activity, eating, and obesity in childhood. Future Child. 2006;16(1):89–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glanz K, Kegler MC. Environments: theory, research and measures of the built environment. Available at: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/constructs/environment/environment.pdf. Accessed September 21, 2009

- 45.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Brashears ME. Social isolation in America: changes in core discussion networks over two decades. Am Sociol Rev. 2006;71(3):353–375 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Litman T. Community Cohesion as a Transport Planning Objective. Victoria, British Columbia: Victoria Transport Policy Institute; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Evans GW, Kantrowitz E. Socioeconomic status and health: the potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:303–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.US Commission of Civil Rights Not in my backyard: Executive Order 12898 and Title VI as tools for achieving environmental justice. Available at: http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/envjust/ej0104.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2009

- 49.Hutch D. The rationale for including disadvantaged communities in the smart growth economic development framework. Yale Law Policy Rev. 2002;20(2).353–368. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedman MS, Powell KE, Hutwagner L, et al. Impact of changes in transportation and commuting behaviors during the 1996 Summer Olympic games in Atlanta on air quality and childhood asthma. JAMA. 2001;285(7):897–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology Asthma Statistics. Available at: http://www.aaaai.org/media/statistics/asthma-statistics.asp. Accessed January 28, 2011

- 52.Prevention Institute The California Endowment, the Urban Institute. “Reducing health care costs through prevention”. Available at: http://www.preventioninstitute.org/documents/he_healthcarereformpolicydraft_091507.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2009

- 53.Boarnet MG, Day K, Alfonzo M, Forsyth A, Oakes M. The Irvine-Minnesota inventory to measure built environments: reliable tests. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(2):153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.US Green Building Council “LEED for neighborhood development”: a prescription for green healthy communities. Available at: http://www.greenhomeguide.org/living green/led_for_neighborhood_development.html. Accessed March 15, 2009

- 55.US Dept of Transportation A summary of highway provisions of SAFETEA-LU. Available at: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/safetealu/summary.htm. Accessed January 3, 2009

- 56.US Environmental Protection Agency Smart Growth Network Awards Program. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/awards/sg-awards-publication-2008.htm. Accessed May 14, 2010

- 57.US Environmental Protection Agency A primer for petroleum brownfields. Available at: http://www.resourcesaver.com/file/toolmanager/Custom093C337F51727.pdf. Accessed January, 21, 2009

- 58.National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Genetic environmental health study. Available at: http://www.news.bio-medicine.org. Accessed February 6, 2009

- 59.US Census Bureau. Available at: http://www.census.gov. Accessed January 28, 2011.

- 60.Dannenberg AL, Bhatia R, Cole BL, Heaton SK, Feldman JD, Rutt CD. Use of health impact assessment in the US: 27 case studies, 1999–2007. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):241–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cole BL, Fielding JE. Health impact assessment: a tool to help policy makers understand health beyond health care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:393–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wachter S. The Determinants of Neighborhood Transformation in Philadelphia—Identification and Analysis: The New Kensington Pilot Study. Philadelphia, PA: William Penn Foundation; July 12, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Downs TJ, Larson HJ. Achieving millennium development goals and health: building understanding, trust and capacity to respond. Health Policy. 2007;83(2–3):144–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]