Abstract

Objectives. People who are incarcerated exhibit high rates of disease, but data evaluating the delivery of medical services to inmates are sparse, particularly for jail settings. We sought to characterize the primary medical care providers for county jail inmates in New York State.

Methods. From 2007 through 2009, we collected data on types of medical care providers for jail inmates in all New York State counties. We obtained data from state monitoring programs and e-mail questionnaires sent to county departments of health.

Results. In counties outside New York City (n = 57), jail medical care was delivered by local providers in 40 counties (70%), correctional medical corporations in 8 counties (14%), and public providers in 9 counties (16%). In New York City, 90% of inmates received medical care from a correctional medical corporation. Larger, urban jails, with a greater proportion of Black and Hispanic inmates, tended to use public hospitals or correctional medical corporations as health care vendors.

Conclusions. Jail medical services in New York State were heterogeneous and decentralized, provided mostly by local physician practices and correctional medical corporations. There was limited state oversight and coordination of county jail medical care.

In 1976, the US Supreme Court issued a landmark decision, Estelle v Gamble, granting prisoners a constitutional right to standard-of-care medical services.1 In fact, prisoners are the only civilian subgroup in the United States with a constitutionally guaranteed right to health care. Delivering medical care to inmates and ensuring continuity of care after release are logistically complex and costly endeavors. A recent nationwide survey found high rates of medical and psychiatric conditions among US prisoners, with nearly 70% of inmates reporting at least 1 chronic illness.2

The challenges of providing standard-of-care medical services to prisoners are manifold. In most states, the correctional system is 2-tiered, composed of prisons and jails. Prisons hold sentenced inmates for periods of a year or longer; jails confine pretrial detainees and inmates sentenced to periods of less than 1 year. Jails pose particular challenges to health care delivery because of the large volume and rapid turnover of inmates. These challenges include discontinuity of care,3 lack of timely access to medical records, lack of trust between patient and provider,4 withdrawal from addictive substances,5 poor discharge planning,6 and loss of medical insurance.7 Unfortunately, data evaluating the delivery of medical services to inmates are sparse, particularly in jail settings. In the neglected field of prison health research, jails constitute a doubly marginalized domain for evaluation and advocacy.

Since the 1970s, US incarceration rates have increased dramatically, with 2.3 million people incarcerated in jails and prisons at the end of 2008.8 An estimated 9 million individual inmates are admitted to and released from jail annually.9 This volume represents an enormous population of medically and psychiatrically vulnerable individuals circulating through the nation's jails.

The delivery of health services within the correctional system ultimately depends on the availability of trained medical care providers. In general, correctional facilities do not constitute a broadly attractive practice setting for most physicians. Prisoners' health needs are not routinely addressed in medical or nursing school curricula.10 After a careful review of publicly available information, we were unable to find any comprehensive information describing the sector (public vs private providers) or training level of medical care providers for any US state. Nor were we able to identify any comprehensive surveys of health care providers for county jail inmates in the medical, social science, or popular literature. The popular press has addressed the issue of correctional medical care through a focus on privatization of these services.11,12 However, analyses characterizing medical service providers for inmates have not been published.

We conducted a statewide survey of medical care providers for county jail inmates, using New York State (NYS) as our study setting. The aim of our study was to determine who provided primary medical care to county jail inmates in NYS. To our knowledge, this is the first statewide study attempting to characterize providers of medical care to county jail inmates.

STUDY SETTING

NYS has the seventh-largest state jail population in the United States.13 The New York City (NYC) correctional system is the second largest metropolitan jail system in the nation, comprising 14 jails, 10 of which are part of the Rikers Island correctional facility.14 In 2008, 107 516 inmates were admitted to NYC jails, and the average daily census was 13 850.15 Outside NYC, there are 61 county jails in the 57 non-NYC counties of NYS. In 2007, 182 779 inmates were admitted to these county jails.16 Jail capacity ranged in size from 6 to 1900. Excluding NYC, the average statewide jail census in 2008 was 16 850 inmates.17

Inmates in NYS carry a disproportionate burden of infectious diseases. HIV and HCV seroprevalence rates among this population are some of the highest in the nation. A 2006 blinded serosurvey of new admissions to NYC jails found HIV seroprevalence rates of 9.7% in women and 4.7% in men.18 In the late 1990s, rates of trichomoniasis among pregnant inmates approached 50%,19 and the incidence of syphilis among women with multiple incarcerations was 1000 times higher than among the general population.20 More recently, implementation of a rapid chlamydia and gonorrhea screening program in NYC jails increased citywide chlamydia reporting rates by 59%.21 In NYS prisons, HCV seroprevalence rates in a 2005 serosurvey were 19.4% for women and 10.4% for men.22 Data on the health profiles of jail inmates in NYS county jails outside NYC are largely unavailable.

Medical services to jail inmates in NYS are decentralized, falling under the jurisdictions and budgets of county government. In contradistinction, the state's prisons are administratively and financially centralized under the Department of Correctional Services. Neither the NYS Department of Health nor the Department of Correctional Services provide oversight over county jail matters. Jail medical services vary by county and usually are contractually placed under the administrative control of the sheriff's office. State-level monitoring of county jail medical services is provided by the Commission of Correction (COC). The COC is an independent governmental agency whose stated mission is to ensure minimum standards of safety and humane treatment of prisoners.23 In NYC, correctional medical services are actively monitored by the Correctional Health Services unit of the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. In September 2009, the state legislature passed a law requiring NYS Department of Health oversight over HIV and HCV care to inmates in state and local correctional facilities.24 Although narrow in scope, the new law revised existing public health law and introduced an unprecedented level of state involvement in county health matters.

METHODS

We ascertained the type of medical care provider contracted to deliver primary medical services to county jail inmates for each county in NYS. The medical service provider was defined as the agency, institution, company, or individual health care professional providing primary physician services at the county jail(s). Additionally, we investigated whether county-level correctional and sociodemographic variables were predictive of the type of medical provider used at the county level. We collected data from 2007 through 2009.

Data Sources

Statewide data were not available through the NYS Department of Health or the Department of Correctional Services. As stated previously neither of these departments oversees local correctional institutions. We identified the COC as the sole governmental agency with a mandate to monitor medical services in all state and local correctional facilities. The COC collects data on medical providers for county jails through passive surveillance. The COC's Medical Forensic Unit actively collects data on inmate deaths and provides technical assistance to correctional facilities requesting health services evaluation. According to the COC's annual report, the COC visits about half of the state's jails yearly.25 Changes in staffing and contracting practices may thus be unreported to the COC until a jail site visit is conducted. Data on the medical providers at county jail facilities were initially unavailable from the COC, despite repeated electronic Freedom of Information Law requests. Ultimately, we had to conduct in-person meetings with COC staff to obtain the available data on medical providers for each county jail. The information was not formatted electronically, and photocopying was not permitted. Thus, we transcribed data directly from COC paper files.

To corroborate and expand on the data provided by the COC, we sent an e-mail to each county's department of health to request information on the medical service provider in the respective county jail(s). The message included the following question: “What type of agency provides routine medical care to local inmates (e.g., public health, academic institution, community physician, private correctional HMO)?” If the initial electronic inquiry was not answered, we made repeated follow-up attempts by e-mail and telephone to both the local department of health and the sheriff's office. Where there was a discrepancy between COC data and local correspondence, we used the local data because they represented more current information.

On the basis of conceptual26 and historical27 data, we created 3 predefined categories of medical care providers: (1) local provider, (2) correctional medical corporation, and (3) public provider. Local providers included private-sector community physicians, physician groups, and nonpublic health care centers operating under contract with the jail. Correctional medical corporations were defined as for-profit entities specializing in the delivery of medical services to inmates. Public facilities included county hospitals and county departments of health.

Because of the significant regional variability in population size, urbanization, income, and racial/ethnic mix, we investigated whether county-level demographics correlated with the choice of medical service provider in county jails. We also examined correctional variables in relation to jail medical care provider. County-level variables included total population, median household income, proportion of county population in poverty, percent unemployment, and nonmetropolitan designation. We obtained these sociodemographic data from the NYS Department of Health.28 Correctional variables included jail population size, proportion of female inmates, racial/ethnic distribution, and percentage pretrial detainees. We obtained correctional data from the COC's end-of-year report for 2007, the most recent report made available electronically after submission of a Freedom of Information Law request.

Statistical Analysis

Our analyses were primarily descriptive. We used descriptive statistics to characterize medical service providers in local county jails, and we performed analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests to determine any differences in jail and county characteristics among the 3 medical provider types. For the purposes of all analyses, we combined data for counties with 2 jails, and the unit for all analyses outside NYC was the county. The 4 counties in which 2 facilities existed used the same medical provider type for both facilities. For NYC, we only present descriptive data, with the unit of analysis being the 5 counties composing the municipal area. Although NYC is divided into 5 counties, the administrative oversight for both the Department of Corrections and Deparment of Health and Mental Hygiene occurs on the municipal level. Because of these administrative differences in jail oversight, we present data and analysis for NYC separate from that for the rest of the state. We used Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to perform analyses.

RESULTS

We obtained data on the medical service provider for all counties. Data for 51 of the 57 counties outside NYC (89%) was obtained via interview with the COC. E-mail questionnaires sent to 57 county health departments garnered a response from 29 (51%) county health directors or liaisons and provided information on the 8 counties for which data were unavailable from the COC. There was only 1 substantive discrepancy between COC data and health department data: for 1 county jail, the COC said medical services were provided by a local physician, but the health department said services were publicly provided. In 2 counties, both sources said the provider was a correctional medical corporation, but they each named a different specific vendor. The COC provided complete data for NYC.

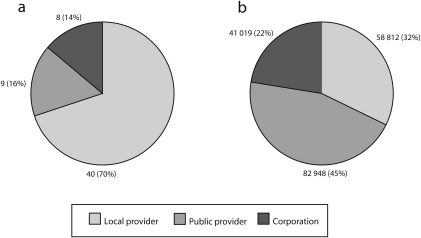

In the 57 counties outside NYC, average jail census ranged in size from 5 to 1540 persons. Pretrial detainees accounted for three fourths of all inmates. Nearly one fifth of all county inmates were not White, as designated by the COC. Women accounted for 17% of all county inmates. Thirty-one counties (54%) were designated as metropolitan.29 The following distribution of medical care providers was observed in NYS county jails (Figure 1): local providers, 40 (70%); correctional medical corporation, 8 (14%); and public facility, 9 (16%). Local providers consisted overwhelmingly of single physicians or small groups of local physicians (37; 92.5%), with a smaller role for local hospitals (3; 7.5%). In the 8 counties using correctional medical corporations, 3 different corporations were identified. In 2 of the 9 counties using a public provider, the commissioner of health served as a de facto jail doctor because of an inability to obtain an alternative contractual arrangement. Two jails contracted with public hospitals, both of which were university affiliated.

FIGURE 1.

County jails (a) and inmate admissions (b) by health care provider type: New York State (excluding New York City), 2007–2009.

Table 1 presents the relationships we found between correctional variables and the type of medical provider. Smaller jails were more likely to be served by local providers, as were jails with fewer Black and Hispanic inmates (P < .05 for both comparisons, by ANOVA). Table 2 shows that smaller counties, those with higher rates of poverty and unemployment, and those with a lower median household income used local providers more frequently. Because of the strong relationship between facility size and medical provider type, we performed an additional analysis in which the distribution of providers was measured by annual volume of inmate admissions. In this analysis (Figure 1), the distribution of medical providers was as follows: local providers, 58 812 inmate admissions (32.2%); correctional medical corporations, 41 019 (22.4%); and public providers, 82 948 (45.4%).

TABLE 1.

County Jail Characteristics by Jail Health Care Provider Type: New York State (excluding New York City), 2007–2009

| Health Care Providers |

||||

| Characteristics | All (n = 57) | Local Provider (n = 40) | Medical Corporation (n = 8) | Public Provider (n = 9) |

| Inmate census, mean* | 270 | 118 | 460 | 776 |

| Inmate admissions, mean* | 3206 | 1470 | 5127 | 9216 |

| Non-White inmates, %* | 24.6 | 17.6 | 42.5 | 39.7 |

| Hispanic inmates, %* | 7.7 | 5.5 | 12.5 | 13.5 |

| Female inmates, % | 17.0 | 17.7 | 16.4 | 14.5 |

| Pretrial detainees, % | 74.9 | 76.2 | 77.5 | 66.4 |

Source. New York State Commission of Correction. End-of-Year Report, 2007. Albany, NY: New York State Commission of Correction; 2008.

*P < .05 for the comparison among 3 provider types by analysis of variance.

TABLE 2.

County Characteristics by Jail Health Care Provider Type: New York State (excluding New York City), 2007–2009

| Health Care Providers |

||||

| Characteristics | All (n = 57) | Local Provider (n = 40) | Medical Corporation (n = 8) | Public Provider (n = 9) |

| Population, mean* | 192 424 | 80 255 | 284 001 | 609 551 |

| Non-White, %* | 8.5 | 6.1 | 13.5 | 14.8 |

| Hispanic, %* | 3.4 | 2.3 | 5.5 | 6.3 |

| Unemployment, %* | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 4.4 |

| Households in poverty, %* | 12.1 | 12.8 | 10.6 | 9.9 |

| Median household income, $* | 45 581 | 41 452 | 53 919 | 56 523 |

| Nonmetropolitan area, %* | 46 | 60 | 0 | 22 |

Source. New York State Department of Health.28

*P < .05 for the comparison among 3 provider types by analysis of variance.

In NYC, the average daily inmate census in 2007 was 13 989 persons. Annual admissions were 108 767 inmates. The average lengths of stay for detainees and for sentenced inmates were 46.3 days and 37.0 days, respectively.15 Women accounted for approximately 10% of all inmates. About 60% of inmates held were pretrial detainees.30

A correctional medical corporation provided care to inmates in 10 of the 11 jails offering medical services.31 Medical care at the sole jail not served by the correctional medical corporation was delivered by a public provider, the NYC Health and Hospitals Corporation. In terms of numbers of inmates cared for, the correctional medical corporation provides care for approximately 90% of NYC's inmates.

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first statewide analysis characterizing medical care providers for county jail inmates. We observed that the majority of county jails outside NYC contract with local physician practices to deliver medical care to their inmates. The number of counties using either public or for-profit providers was relatively small. In NYC, medical care for the vast majority of inmates was provided by a for-profit correctional medical corporation. The relatively small role played by the public sector is somewhat surprising, given the sociodemographic background of jail inmates. Academic medicine is notably absent from correctional health care in NYS.

For county jails outside NYC, we were able to determine some relationships between the medical service provider and both county characteristics and correctional characteristics. The sizes of both the county populations and the jail populations were inversely related to the use of local providers. In other words, smaller counties tended to contract jail medical services to local physicians and physician groups. We noticed a strong trend for counties with a larger proportion of Black and Hispanic jail inmates to contract with either a public entity or a for-profit corporate vendor. No correctional medical corporations were found in counties designated as nonmetropolitan.

Over the past decade, significant media coverage has been focused on the role of for-profit correctional medical corporations in filling a niche in correctional health care.11 Despite media attention to this issue, the prevalence of privatization of medical services in the nations' jails is not known. Narrowly defined, privatization—as measured by the presence of for-profit, correctional medical corporations—accounted for a small number of county jails in NYS. Only 8 counties out of 57 (14%) contracted to receive medical services from private corporations. However, in contracting with larger jails, correctional medical corporations provided medical care to more than one fifth of NYS county jail inmates. In NYC, approximately 90% of inmates received care from a correctional medical corporation. Our analysis suggests that these corporations tend to serve the same types of jails served by the public sector: large urban jails with a high proportion of non-White inmates.

What is at stake in the care of county jail inmates? Inmates are disproportionately affected by substance use and mental health disorders as well as chronic and infectious diseases.2,32,33 Former inmates often return to communities already struggling with poor health profiles.34 On an individual level, quality medical care in jails is a constitutional and human right, essential to ensure proper treatment of existing medical and mental health conditions.

There are also significant public health implications of poor medical care in jails. A striking example is HIV care. In a survey conducted in NYC, longitudinal engagement in HIV care with a single community provider was associated with a decreased rate of incarceration among high-risk women.35 Incarceration and release are associated with interruption of HIV treatment, which may lead to poor clinical outcomes, increased HIV transmission, and the potential emergence of treatment-resistant strains.3,36 In NYC, the medical needs of inmates and their communities of origin have led to numerous programmatic interventions including universal HIV screening, treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, and enhanced discharge planning services.37 Finally, alternatives to incarceration have been promoted as the underlying solution to much of the treatment burden placed on correctional medical systems. For example, it has been demonstrated that inmates are less likely to receive substance abuse treatment while in jail than when on probation.9

The recent passage of legislation to monitor HIV and HCV treatment in county jails underscores the importance of providing standard-of-care treatment to inmates. Our study was conducted over a period of 2 years before the passage of this legislation, and our findings underscore the need for comprehensive evaluation of medical services in county jails. Such oversight will require significant efforts to coordinate a fragmented and heterogeneous group of medical providers. In fact, the law grants a 2-year grace period for oversight of local correctional facilities; by contrast, state prisons will be monitored immediately. Funding will also constitute a significant challenge to implementation. In NYS, state monies cannot be used to fund county jail health care, with the exception of limited vaccination and epidemic control programs. Therefore, the costs of providing, evaluating, and improving jail medical care must be met by county budgets, and the new law will place further strain on the finances of local government.

Our study has several limitations. The data represent a cross-sectional analysis. Shifts in the distribution of providers may have occurred but were not reflected in the data at the time of analysis. We could not determine time trends or historical shifts in the distribution of medical providers. Furthermore, we did not obtain information regarding the reasons for selection of a provider or the fiscal implications of vendor choice. Our analysis was limited to primary medical care and excluded access to mental health services and subspecialty care, both of which are critical services for jail inmates.

Informal data gathered in the course of the study suggest that nurses and physician assistants play a crucial role in providing primary care services to jail inmates. Because our predefined analysis centered on a description of physician services, data on allied health professionals collected in the course of our study was incomplete. Further study is needed to define the extent of nonphysician involvement in delivering health services to jail inmates. Finally, we were unable to determine any association between medical provider and the quality of medical care. Such analysis would require much greater levels of transparency and collaboration between researchers and county jail administrators. Despite these limitations, we were able to ascertain data for all facilities, yielding a complete picture of medical providers in jails statewide.

A significant knowledge gap remains in our understanding of the impact of incarceration on the well-being of individuals and communities. Given the unprecedented rise in US incarceration rates, correctional health care is a critical area for research and advocacy. Although reports show that the NYS prison census declined in 2009 for the first time since the 1970s,38 a similar decrease has not been observed in New York county jails.39 We believe that a drastic reduction in the use of incarceration as social policy is the key factor in eliminating the health disparities arising from imprisonment.

Our analysis of medical providers in NYS county jails discovered a notable diversity of medical providers combined with a dearth of accountability and oversight. A disparate network of local providers delivered care in the majority of jails with a significant role played by correctional corporations in larger, urban facilities. Given the findings of our study, coordination and improvement of these disparate medical delivery systems appears to be an urgent, if distant, goal. Jail inmates are a vulnerable population, and high-quality health services are an essential need for them from both an individual and a public health standpoint.

Acknowledgments

Noga Shalev received funding for this study from the National Institutes of Health, Health Disparities Loan Repayment Program.

Noga Shalev would like to acknowledge Katharine Lawrence for her dedicated research assistance and Sarah Oppenheimer for her invaluable editorial contributions.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because the study did not involve research on human participants.

References

- 1. Estelle v Gamble, 429 US 97 (1976)

- 2.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, et al. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):666–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;301(8):848–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellin E. The prison patient. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(12, pt 1):1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karberg J, James D. Substance Dependence, Abuse and Treatment of Jail Inmates, 2002. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2005. NCJ publication 209588 [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Olphen J, Freudenberg N, Fortin P, Galea S. Community reentry: perceptions of people with substance use problems returning home from New York City jails. J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):372–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J, Vlahov D, Freudenberg N. Primary care and health insurance among women released from New York City jails. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(1):200–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabol WJ, West HC, Cooper M. Prisoners in 2008. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. NCJ publication 228417 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck A. The importance of successful reentry to jail population growth. Paper presented at: Jail Reentry Roundtable, Urban Institute; June 27, 2006; Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alemagno SA, Wilkinson M, Levy L. Medical education goes to prison: why? Acad Med. 2004;79(2):123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zielbauer P. Harsh medicine: as health care in jails goes private, 10 days can be a death sentence. New York Times. February 25, 2007:A1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zigmond J. Help from the outside: states use variety of contractors to provide healthcare for prisoner population. Mod Healthc. 2007;37(12):52–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck AJ, Harrison P. Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2005. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. NCJ publication 213133 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minton TD, Sabol WJ. Jail Inmates at Midyear 2008—Statistical Tables. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. NCJ publication 225709 [Google Scholar]

- 15.City of New York Dept of Correction DOC statistics. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doc/html/stats/doc_stats.shtml. Accessed February 1, 2010

- 16.New York State Commission of Correction End of Year Report, 2007. Albany, NY: New York State Commission of Correction; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Donell DE. 2008 CrimeSTAT Report. Albany, NY: New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begier EM, Bennani Y, Forgione L, et al. Undiagnosed HIV infection among New York City jail entrants, 2006: results of blinded serosurvey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(1):93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shuter J, Bell D, Graham D, Holbrook KA, Bellin EY. Rates of and risk factors for trichomoniasis among pregnant inmates in New York City. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25(6):303–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blank S, Sternberg M, Neylans LL, Rubin SR, Weisfuse IB, St Louis ME. Incident syphilis among women with multiple admissions to jail in New York City. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(4):1159–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pathela P, Hennessy RR, Blank S, Parvez F, Franklin W, Schillinger JA. The contribution of a urine-based jail screening program to citywide male chlamydia and gonorrhea case rates in New York City. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(2 suppl):S58–S61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith L. HIV/AIDS epidemiology in New York State. Paper presented at: HIV Clinical Scholars Program, New York State AIDS Institute; October 17, 2007; New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 23.New York State Commission of Correction Web site. Available at: http://www.scoc.state.ny.us/index.htm. Accessed January 18, 2010

- 24. S 3842 (NY 2009)

- 25.New York State Commission of Correction Annual report 2008. Available at: http://www.scoc.state.ny.us/pdfdocs/annualreport_2008.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2010

- 26.Turner GM. A profile of the health sector in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20(suppl 3):31–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shalev N. From public to private care: the historical trajectory of medical services in a New York City jail. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):988–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.New York State county health indicator profiles New York State Dept of Health Web site. Available at: http://www.health.state.ny.us/statistics/chip. Accessed January 25, 2010

- 29.United States Dept of Agriculture 2003 rural-urban continuum codes. Economic Research Service Web site. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/RuralUrbanContinuumCodes/2003/LookUpRUCC.asp?C=R&ST=NY. Accessed March 22, 2010

- 30.City of New York Dept of Correction Facilities overview. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doc/html/about/facilities_overview.shtml. Accessed March 26, 2010

- 31.Office of the New York State Comptroller New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: Contracted Health Care Services for New York City Prison Inmates. New York, NY: Office of the New York State Comptroller, Division of State Government Accountability; 2007:1–25 Report 2005-N-5. Available at: http://osc.state.ny.us/audits/allaudits/093007/05n5.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases among correctional inmates: transmission, burden, and an appropriate response. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):974–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e7558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(2):214–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheu M, Hogan J, Allsworth J, et al. Continuity of medical care and risk of incarceration in HIV-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Womens' Health (Larchmt). 2002;11(8):743–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Pendo M, Loughran E, Estes M, Katz M. Highly active antiretroviral therapy use and HIV transmission risk behaviors among individuals who are HIV infected and were recently released from jail. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(4):661–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jordan AO, Gbur M, Cruzado-Quinones J. HIV Continuum of care: from Rikers Island intake jail to community provider. Presented at: National Conference on Correctional Health Care; Chicago, IL; October 21, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz J. Report finds states holding fewer prisoners. New York Times. March 17, 2010:A15 [Google Scholar]

- 39.New York State Commision of Correction Inmate population statistics. Available at: http://www.scoc.state.ny.us/pop.htm. Accessed June 1, 2010