Abstract

Objectives

This study investigates alterations in myocardial microvasculature, fibrosis and hypertrophy before and after mechanical unloading of the failing human heart.

Background

Recent studies demonstrated the pathophysiologic importance and significant mechanistic links between microvasculature, fibrosis and hypertrophy during the cardiac remodeling process. The effect of left ventricular assist device (LVAD) unloading on cardiac endothelium and microvasculature is unknown and its influence on fibrosis and hypertrophy regression to the point of atrophy is controversial.

Methods

Hemodynamic data and left ventricular tissue were collected from patients with chronic heart failure at LVAD implant and explant (n=15), and from normal donors (n=8). New advances in digital microscopy provided a unique opportunity for comprehensive whole-field, endocardium-to-epicardium evaluation for microvascular density, fibrosis, cardiomyocyte size and glycogen content. Ultrastructural assessment was done with electron microscopy.

Results

Hemodynamic data revealed significant pressure unloading with LVAD. This was accompanied by a 33% increase in microvascular density (p=0.001) and a 36% decrease in microvascular lumen area (p=0.028). In agreement with these findings we also identified immunohistochemical ultrastructural evidence of endothelial cell activation. In addition, LVAD unloading significantly increased interstitial and total collagen content without any associated structural, ultrastructural or metabolic cardiomyocyte changes suggestive of hypertrophy regression to the point of atrophy and degeneration.

Conclusions

LVAD unloading resulted in increased microvascular density accompanied by increased fibrosis and no evidence of cardiomyocyte atrophy. These new insights into the effects of LVAD unloading on microvasculature and associated key remodeling features may guide future studies of unloading-induced reverse remodeling of the failing human heart.

Keywords: heart failure, remodeling, left ventricular assist device, unloading, microvasculature

Introduction

The number of patients who receive left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) is rapidly increasing (1), which offers a valuable opportunity for in-depth investigations into human cardiac biology (2,3). The examination of paired human tissue before and after LVAD therapy enables one to correlate functional and structural effects of various therapies combined with LVAD. These advantages along with the safety platform LVAD offers make this patient population a precious “research vehicle” for investigating new remodeling and regenerative therapies for heart failure (HF). Yet, in order for these promises to be fulfilled, we must first understand the fundamental impact of mechanical unloading on the failing human heart.

Pathophysiologic models derived from basic science and animal studies focus on the role of excess load in driving a vicious cycle of cardiac remodeling (4). This mechanistic model led to the hypothesis that mechanical unloading would disrupt this cycle and improve function of the failing human heart (2,3,5). Despite the opportunity afforded by the use of LVAD in clinical practice, the effects of mechanical unloading on basic remodeling features are still poorly understood or unknown (2,3,5). It is noteworthy that the direct effect of mechanical unloading on myocardial endothelium and microvasculature is unknown and its effect on the degree of hypertrophy regression, possibly to the point of atrophy, is controversial (2,5). Furthermore, reports of the LVAD unloading effects on cardiac fibrosis have been conflicting, with some showing reduction in fibrosis and others an increase (2,3,5,6). The need for further understanding of the impact of unloading on specifically these key remodeling features is now even more acute as there is increasing robust evidence demonstrating important mechanistic links between microvasculature, fibrosis and hypertrophy during the cardiac remodeling process (7,8).

Here, we use whole field, endocardium-to-epicardium digital microscopy (9,10) coupled with ultrastructural and functional evaluation to examine the influence of mechanical unloading on these three central features of cardiac remodeling. The application of state-of-the-art digital histopathology for examination of left ventricular myocardial samples acquired from normal donors and from patients with end-stage chronic heart failure markedly increases the volume of tissue objectively and quantitatively analyzed, and provides a new standard for future studies in the field of mechanical unloading and cardiac remodeling.

Methods

A. Study population

The study group comprised of fifteen consecutive patients who received HeartMate I LVAD (Thoratec Corporation, Pleasanton, CA) as a bridge to transplantation due to chronic end-stage heart failure. Patients who received LVAD support due to acute heart failure (n=11), were not included. Eight age-matched donors whose hearts were found to be functionally and structurally normal but were not suitable for transplantation for non-cardiac reasons, were used as normal controls.

B. Clinical data collection

We collected patient demographic data, data on comorbidities, echocardiography results, invasive hemodynamic data and laboratory data within 24 hours before LVAD implantation and again between weeks two and four after LVAD implantation.

C. Histochemical stains and immunohistochemistry

Myocardial tissue was prospectively obtained from the LV apical core at LVAD implantation. At the time of cardiac transplantation, the tissue was obtained from the surrounding apical area, at least 1 cm distant from the LVAD inflow cannula (to avoid inclusion of reactive tissue changes). Tissue preparation and use of Masson’s trichrome stain for collagen content evaluation, periodic acid Schiff reaction (PAS) for cardiomyocyte size evaluation, the combination of PAS and PAS with diastase (PASD) for demonstration of glycogen content and immunostaining for the endothelial cell protein CD34 and the endothelial activation marker major histocompatibility complex class 2 (MHC-2) are detailed in Supplemental Material. To achieve high degree of reproducibility we avoided manual staining and both the histochemical stains and the immunohistochemistry experiments were performed using automatic staining systems (see Supplemental Material).

D. Whole-field digital microscopy

Advanced digital microscopy allowed examination of the entire heart tissue areas from the epicardium to the endocardium. Whole-slide images were analyzed with the ScanScope XT system equipped with the ImageScope 10.0 image analysis algorithms (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA) (9,10).

1. Microvasculature evaluation

We used the ImageScope 10.0 Microvessels analysis algorithm (10) to distinguish endothelial cells from nonspecific staining of surrounding tissue by applying appropriate dark and light thresholds (Figure 1). Only myocardial tissue cuts oriented in cross- section (epicardium to endocardium) were analyzed. Microvascular density was defined as “number of microvessels”/“total tissue analysis area”.

Figure 1. Microvasculature evaluation.

Panels A and B: Left ventricular mid- myocardium immunohistochemically stained for the endothelial cell protein CD-34 (brown color). Algorithm thresholds were appropriately adjusted to allow microvascular evaluation within selected regions of interest. Panel A: 20x magnification, Panel B: 60X magnification

Panel C. Automatic completion of stained microvessels by the analysis algorithm enables measurements like vessel perimeter, lumen area etc.

2. Collagen content evaluation

We set the staining color threshold of the ImageScope 10.0 Colocalization analysis algorithm to accurately identify collagen based on its blue color (Figure 2, panels A and B). “Interstitial Fibrosis” was defined as the collagen content determined in the interstitial spaces and endomysial/perimysial spaces including the collagen content around capillaries and small vessels (i.e. vessels with diameter <60μm) found within those spaces. The “total” collagen content (“total fibrosis”) was determined by including in our analysis the whole-field stained tissue without excluding any areas (Figure 2, panels C, D and E). The collagen content around medium and large vessels (i.e. vessels with diameter >60μm), “perivascular fibrosis”, was separately calculated by subtracting the “interstitial/perimysial/endomysial” collagen content from the determined “total” collagen content (i.e. “total fibrosis” minus “interstitial fibrosis”).

Figure 2. Collagen content evaluation.

Sections were stained with Masson’s Trichrome stain- collagen stains blue. Panel A: Representative stained image from mid-myocardium before digital analysis was performed. Panel B: The section was digitally analyzed for collagen content based on color thresholds. The analysis algorithm “highlighted” collagen as dark blue and was sufficiently sensitive and accurate to exclude even small nuclei (arrows) within the fibrous tissue. Panel C: “Interstitial fibrosis” was defined as the collagen content determined in manually selected regions of interest that excluded bands of perivascular fibrosis associated with any vessel with diameter > 60μm (i.e. medium/large vessels). Panel D: Whole slide, epicardium-to-endocardium image showing superimposed all the regions selected for assessment of “interstitial fibrosis” based on the criterion described in panel C (0.5x magnification). Panel E: “Total” collagen content (“total fibrosis”) was determined by including in our analysis the whole-field stained tissue without excluding any areas (0.5x magnification).

3. Cardiomyocyte size and glycogen content evaluation

Cardiomyocytes were accepted for size measurement if they met specific criteria detailed in Supplemental Material. Glycogen content was evaluated by adjusting the staining color thresholds of the algorithm to precisely capture the magenta PAS-positive stain. To exclude non-glycogen, magenta PAS-positive staining substances, a paired adjacent slide was analyzed following glycogen depolymerization with the PASD reaction (see Supplemental Material). Next, using our algorithm, glycogen stores could be evaluated by digital subtraction of the images derived from two paired adjacent slides stained with PAS and PASD each. Glycogen content was defined as the percentage of magenta stained area for the PAS stained slide minus the PASD stained slide for identical regions of interest.

E. Electron microscopy studies

Tissue was examined according to a classification scheme which was based on previous work in the field by our group (11), as well as according to our pre-specified research hypotheses for this study. Supplemental Material section describes the specific parameters included in this ultrastructural classification scheme to assess microvasculature and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, degeneration and atrophy.

Statistical analysis

An independent samples t-test, a paired t-test and a Wilcoxon signed-ranks test were used to assess the statistical significance of differences observed. Our Institutional Review Board approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from patients before their enrolment.

Results

A. Clinical and hemodynamic data

Patient demographics and clinical and hemodynamic characteristics are shown in table 1. Cardiac index and left and right sided pressures virtually normalized during LVAD support revealing significant LVAD induced pressure unloading (Table 2). Medications used during LVAD support are listed in Supplemental Material.

Table 1.

Individual patient characteristics

| Patient # | Age/gender | Heart Failure Etiology | DM | Pre Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation | Duration of support (days) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR bpm | SBP mmHg | LVEF (%) | RA mmHg | PAs mmHg | PCWP mmHg | CI (l/min/m2) | PVR (WU) | Na (mmol/l) | Cr (mg%) | Hgb (g/dl) | |||||

| 1. | 57/M | IDC | No | 106 | 90 | 20 | 12 | 55 | 30 | 1.75 | 2.7 | 131 | 1 | 11 | 183 |

| 2. | 55/M | IDC | no | 120 | 95 | 10 | 13 | 70 | 26 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 133 | 1.2 | 11.2 | 63 |

| 3. | 39/M | IDC | no | 115 | 85 | 10 | 12 | 53 | 32 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 124 | 2.1 | 10 | 24 |

| 4. | 59/M | IDC | no | 95 | 90 | 10 | 9 | 55 | 23 | 1.7 | 4.8 | 128 | 1 | 13.2 | 33 |

| 5. | 50/M | IDC | yes | 129 | 90 | 15 | 10 | 62 | 30 | 1.8 | 3 | 148 | 3 | 10.6 | 70 |

| 6. | 51/M | IDC | no | 120 | 85 | 10 | 9 | 60 | 25 | 2 | 3.4 | 144 | 1.7 | 9 | 28 |

| 7. | 17/M | IDC | no | 120 | 110 | 20 | 20 | 56 | 37 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 135 | 1.6 | 14 | 212 |

| 8. | 62/M | ICM | no | 118 | 80 | 5 | 8 | 50 | 25 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 131 | 1.2 | 13.6 | 86 |

| 9. | 49/M | ICM | no | 101 | 95 | 15 | 5 | 39 | 22 | 2 | 1.5 | 135 | 1.3 | 10.1 | 283 |

| 10. | 64/M | ICM | yes | 80 | 95 | 15 | 11 | 102 | 31 | 2.8 | 6.5 | 135 | 1.9 | 10 | 187 |

| 11. | 48/M | ICM | no | 91 | 105 | 20 | 8 | 88 | 32 | 2.8 | 6.0 | 133 | 1.6 | 11 | 113 |

| 12. | 49/M | ICM | no | 125 | 95 | 22 | 15 | 40 | 23 | 3.18 | 0.6 | 132 | 2.5 | 13 | 79 |

| 13. | 58/M | ICM | no | 95 | 80 | 25 | 12 | 61 | 29 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 131 | 1.9 | 12 | 22 |

| 14. | 57/M | ICM | no | 124 | 95 | 10 | 17 | 45 | 30 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 135 | 0.9 | 13 | 21 |

| 15. | 57/M | ICM | no | 101 | 80 | 20 | 7 | 47 | 20 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 132 | 2.6 | 10.8 | 21 |

CI = cardiac index; Cr: serum creatinine; DM: diabetes mellitus; Hgb = hemoglobin; HR = heart rate; ICM = ischemic cardiomyopathy; IDC = idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; Na: serum sodium; PAs = systolic pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; RA = right atrial pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure; WU = Wood unit.

Table 2.

Hemodynamic parameters pre and post left ventricular assist device (LVAD) unloading (n=15)

| Pre LVAD | Post LVAD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, bpm | 109.3±14.8 | 82±29 | 0.01 |

| Systemic arterial blood pressure, mmHg | |||

| Systolic | 91 ±9 | 115±21 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic | 55± 8 | 63±13 | 0.04 |

| Right atrial pressure, mmHg | 11.2±3.9 | 10.8±5.3 | 0.776 |

| Pulmonary artery pressure, mean, mmHg | 41.9±10.4 | 22.3±4.4 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary artery pressure, diastolic, mmHg | 31.7±5.6 | 16.1±5.5 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mmHg | 27.7±4.7 | 10.8±4.4 | <0.001 |

| Cardiac index, l/m2/min | 2.1± 0.6 | 2.9±0.3 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, Wood units | 3.3±1.5 | 2.0±0.5 | 0.008 |

Values are means ± SD

B. Structural, ultrastructural and metabolic data

The total tissue area under examination included all of the myocardial tissue sectioned and mounted on the slides (Figure 2, panels D and E). As such, the final average tissue analysis area per patient sample was 74.9 ± 49.5 mm2.

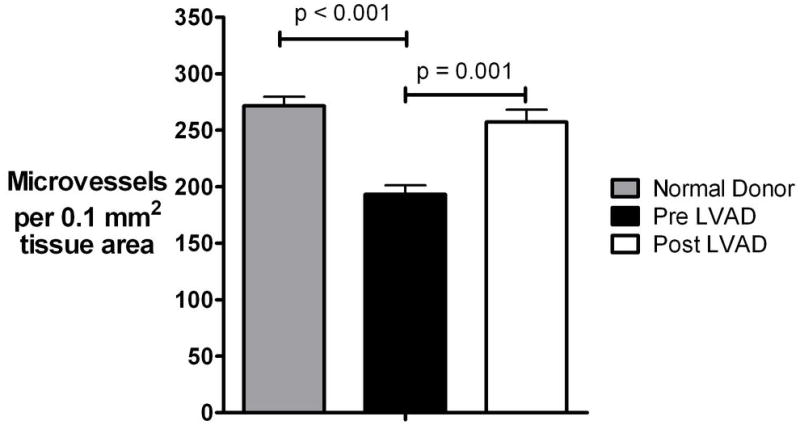

i) Microvasculature studies

Microvascular density as assessed with digital microscopy was found to be significantly decreased in the failing hearts compared to the normal donor hearts. Following LVAD unloading there was a 33% increase in microvascular density (p=0.001, figure 3). Unloading effects on the microvasculature did not differ between ischemic and non-ischemic chronic HF patients.

Figure 3. Microvascular density.

(Plots represent means ± standard error), LVAD: left ventricular assist device

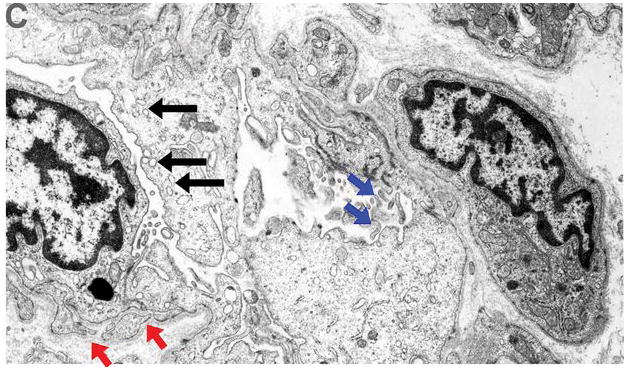

Next, we examined the ultrastructural effects of LVAD unloading on microvasculature by electron microscopy studies in a randomly selected subset of HF patients (n=5, patient #1, #2, #6, #8, #14). In agreement with the digital histopathology data revealing post LVAD increase in microvascular density, we identified ultrastructural evidence of post LVAD endothelial cell activation (pre LVAD grading: 0.4± 0.5 vs. post LVAD: 1.8 ± 1.0, p = 0.038). The most striking of these post LVAD changes were: (a) basal lamina reduplication, (b) increase in the number of lumenal cytoplasmic processes and irregular surface membrane projections, (c) increased size of nuclei and increased number of cytoplasm organelles protruding into the capillary lumen, which significantly decreased the lumenal area (figure 4) (12). In further agreement with these findings the post LVAD expression of the endothelial activation marker MHC-2 was consistently found to be increased in all of our patient samples (see Supplemental Results).

Figure 4. Endothelial cell activation.

Ultrastructural appearance (10,000x magnification, patient #2) of capillaries pre and post left ventricular assist device (LVAD) unloading revealed strong evidence of endothelial cell activation post LVAD. Panel A (pre LVAD). Red arrowheads: basal lamina, small blue arrows: cytoplasmic organelles and nuclei, big red arrow: capillary lumen.

Panel B (post LVAD). Red arrowheads: basal lamina reduplication, small blue arrows: increased nuclei size and increased cytoplasm organelles protruding into the capillary lumen- irregular luminal surface (big red arrow)

Panel C (post LVAD). Basal lamina reduplication (red arrows), increased nuclei and cytoplasmic size with increased pinocytotic vesicles protruding into the capillary lumen (black arrows), and numerous irregular lumenal and surface membrane projections (blue arrows), all indicative of endothelial activation.

Because we discovered these specific ultrastructural microvasculature changes we further proceeded with application of the unique tools of digital microscopy at the structural level and we estimated the average microvessel lumenal area (defined as “total lumenal area measured in the entire tissue analysis area”/“number of microvessels measured in the entire tissue analysis area”). In agreement with the ultrastructural findings, the average lumenal area was found to be decreased post LVAD unloading by 36% (p=0.028, figure 5). However, the fact that we had concomitantly found increased microvessel density post LVAD raised the possibility that even if the average microvascular lumenal area (i.e. lumenal area per microvessel) is decreased, the total microvessel lumenal area (i.e. the sum of the lumenal areas of all microvessels in the entire examined myocardial area), might not be decreased. For this reason we also assessed the “total lumenal area measured in the entire tissue analysis area”/“entire tissue analysis area” and this value was found to be decreased by 18% post LVAD.

Figure 5. Microvascular lumenal area.

(Plots represent means ± standard error), LVAD: left ventricular assist device

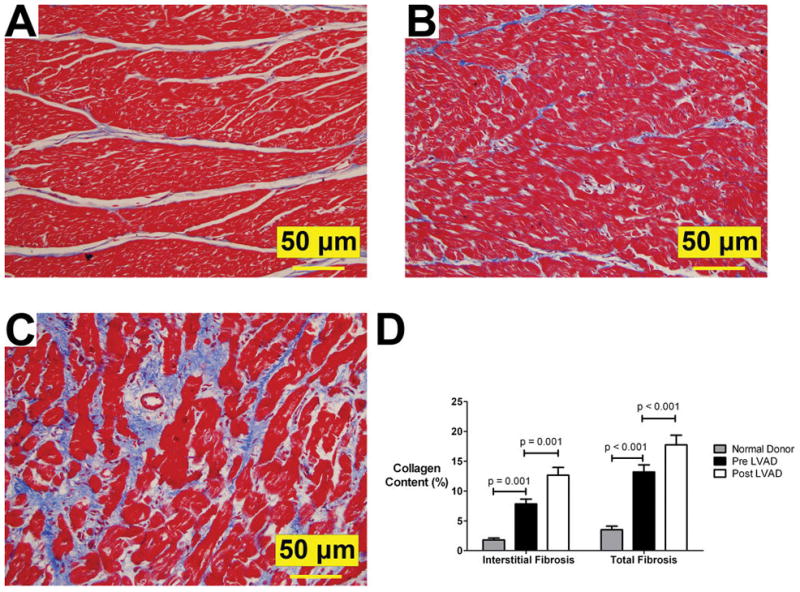

ii) Fibrosis studies

“Interstitial” and “total fibrosis” were significantly increased in failing hearts compared to normal donor hearts, and increased further after LVAD unloading by 61% (p<0.001) and 35% (p=0.001), respectively (figure 6). The fibrosis around medium and large vessels, i.e. “perivascular fibrosis”, was found to be similar in pre and post LVAD samples. Therefore, the increase in “total fibrosis” was driven exclusively by increase of “interstitial fibrosis”. The effect on fibrosis was similar between the ischemic and the non-ischemic chronic HF patients.

Figure 6. Cardiac fibrosis.

Panel A (normal donor heart), panel B (pre LVAD), panel C (post LVAD): Increased fibrosis (Masson’s stain- collagen content stains blue) post 63 days of LVAD-induced unloading (patient # 2); 20x magnification;

Panel D: Interstitial fibrosis and Total fibrosis – see text for definitions (Plots represent means ± standard error).

LVAD: left ventricular assist device

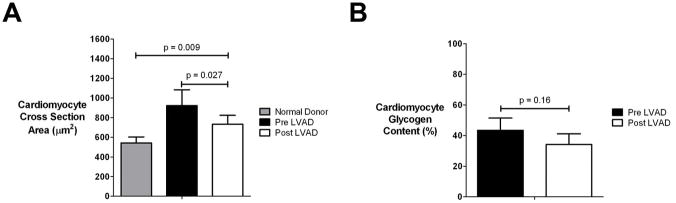

iii) Cardiomyocyte studies

Cardiomyocyte size, as assessed by digital microscopy, decreased after unloading (pre LVAD cardiomyocyte CSA: 923 ± 336 μm2 vs post LVAD CSA 733 ± 194 μm2, p=0.027), but not beyond that of normal donor hearts (donor CSA: 543 ± 119 μm2, p=0.009), a finding that might have suggested unloading induced atrophy (figure 7, panel A). The results were similar for the subset of patients that underwent prolonged duration (> 6 months) of mechanical unloading. Similarly, the comparison of the ultrastructural electron microscopy findings of the normal donor and pre LVAD myocardial samples with the post LVAD tissue revealed no evidence suggestive of hypertrophy regression to the point of cardiomyocyte degeneration and atrophy. Specifically: (1) myofilament loss (1.0± 0.8 vs 1.0± 1.0, p=0.65), (2) mitochondria abnormalities including changes in number, size, shape and cristae appearance (1.2 ± 0.5 vs 1.2 ± 0.8, p=1.0) and (3) dilatation of sarcotubular elements (1.6± 0.5 vs 1.0± 0.8, p=0.18) were all comparable pre and post LVAD unloading. The rest of the ultrastructural parameters included in our electron microscopy classification scheme were also found to be similar before and after LVAD unloading. In agreement with these findings, the cardiomyocyte glycogen content, as assessed by digital microscopy, was unchanged between pre LVAD and post LVAD unloading (figure 7, panel B). Also, there was no difference between ischemic and non-ischemic chronic HF patients.

Figure 7. Cardiomyocyte studies.

Panel A. Cardiomyocyte size evaluation

Panel B. Cardiomyocyte glycogen stores evaluation

(Plots represent means ± standard error), LVAD: left ventricular assist device

Discussion

This study demonstrates that pulsatile mechanical unloading of the failing heart increases microvascular density. In agreement with this finding, we found ultrastructural and immunohistochemical evidence of post LVAD endothelial cell activation. The decrease of the microvascular lumenal area observed by ultrastructural electron microscopy was confirmed by structural digital microscopy. The vascular changes were accompanied by increased fibrosis and reduced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy without any structural, ultrastructural or metabolic evidence of outright degeneration and atrophy. To our knowledge, this is the first study which examines the direct effects of unloading on myocardial microvasculature and endothelium and simultaneously correlates the effects of LVAD unloading on microvasculature, fibrosis and hypertrophy. Furthermore, the adoption of whole-field digital histopathology (9,10) allows comprehensive endocardium-to-epicardium examination and avoids bias intrinsic to the selection of random fields, the chief means of analysis used in previous studies.

Mechanistic links between microvasculature, fibrosis and hypertrophy

A large body of work has shown that endothelial and epithelial cells can transition to fibroblast or mesenchymal phenotypes and through this endothelial to mesenchymal transition contribute to fibrosis of many tissues (7, 13). In a recent seminal paper that used lineage tracing in a mice model of aortic banding, Zeisberg et al, showed that cardiac fibrosis was directly related to endothelial cells as those were activated and adopted a mesenchymal or fibroblastic phenotype via pathways directly implicated in maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy (7). These findings were widely perceived in both the basic and clinical research arenas as the establishment of a significant pathophysiological link between myocardial microvasculature, fibrosis and hypertrophy (8). Other progenitor cells that could serve as fibroblast precursors include pericytes, fibrocytes derived from bone marrow and myofibroblasts (alpha-smooth muscle actin-containing contractile cells). Regarding the latter, alpha-smooth muscle actin immunostaining was very rarely identified in cells other than contractile cells of the vessel walls and was not different between our pre- and post-LVAD samples (data not shown).

Our study of human patients revealed post LVAD increase in microvascular density, a finding that is in agreement with experimental data of unloading by means of heterotopic transplantation (14). Our ultrastructural analysis provided mechanistic insights by revealing strong evidence of post-LVAD endothelial cell activation. Previous animal models of angiogenesis in myocardial and skeletal muscle revealed that ultrastructural endothelial cell activation represents one of the early stages of capillary growth and arteriogenesis (12,15). Furthermore, the increased microvascular density we identified was accompanied by increased fibrosis and this suggests that the mechanistic link between the endothelium and cardiac fibrosis might apply to human myocardium. Obviously, direct proof for such a mechanism requires sophisticated lineage tracing possible only in genetically manipulated animal models (7,8). Of note, work done in our laboratory has increasingly shown that endothelial proliferation and migration, hallmarks of angiogenesis, must be balanced by mechanisms that stabilize the endothelium, so that a functional vascular network may be established and maintained (16–18). The findings of this study suggest an imbalance in these competing signals after LVAD implantation (19), which possibly results in increased microvascular density and endothelial activation that may contribute to cardiac fibrosis.

Clinical research implications

Future studies need to address not only the association of increased microvascular density, endothelial activation and cardiac fibrosis, but must also identify the primary triggers. One possibility is that the myocardial microvessel growth is stimulated by mechanical and hemodynamic factors associated with increased blood flow (20). However, while cardiac output is increased by LVAD (as also found in our study), previous positron emission tomography studies have shown that this is not accompanied by increased coronary flow (21,22). Of note, in a Harefield group study, even though all subjects showed varying degrees of LVAD induced myocardial recovery, post LVAD coronary flow reserve was impressively impaired and the authors concluded that this finding required further investigation (21). This latter finding could be explained by the decreased microvasculature lumen area found in our study by both whole-field digital microscopy at the structural level and by electron microscopy at the ultrastructural level.

Whether LVAD unloading results in increase or decrease in fibrosis is controversial (2,3,5,6,23). The reasons for differing findings in various studies are unclear but may be related to the methodology used (2,3,5,23). Our use of digital histopathology (9, 10) enabled us to examine the whole field from endocardium to epicardium which significantly reduced any selection or observer bias and removed the confounding effect of endocardial or epicardial sampling, known to be associated with different degrees of fibrosis (24). In addition, our results were derived from a total myocardial analysis area that greatly exceeds that of previous reports (2, 5). Recenty published human data demonstrated increase in post LVAD cardiac content of angiotensin I, angiotensin II and norepinephrine (6, 25), findings compatible with the increased fibrosis observed in our study. Furthermore, experimental studies of heterotopic transplant also showed unloading-induced increase in myocardial fibrosis (26,27).

The hypertrophy regression observed in our study is in agreement with experimental heterotopic transplantation data (14,26,27) and also with other studies in humans showing that LVAD unloading reversed the altered cardiac expression and function of natriuretic peptides and receptors along with parallel reductions in myocardial mass and myocyte size (3). However, whether in human failing hearts unloaded by means of LVAD hypertrophy regresses to the point of atrophy and degeneration is controversial and requires further investigation (2,3,5). In our study of failing human hearts, the absence of post LVAD cardiomyocyte atrophy and degeneration was not based only on cardiomyocyte size data but was reinforced both by ultrastructural electron microscopy findings and metabolic findings. Given that atrophy has been associated with significantly increased glycogen concentration (28,29), the lack of change of glycogen content after LVAD unloading observed in our study (with a trend to decrease) does not seem to be compatible with LVAD-induced cardiac atrophy. To our knowledge the question of LVAD induced atrophy and degeneration has not been specifically addressed by previous LVAD clinical studies on ultrastructure or quantitative metabolic changes and from this perspective our study adds to the literature.

Study Limitations

A number of limitations of our study need to be addressed in future investigations. First, to focus on the role of mechanical unloading on the failing heart, drugs that are hypothesized to have direct effects on remodeling would not be employed, or their use would be randomized. However, we do note that only two of our patients were treated with such medications and their results were not significantly different from patients not given any such medications. Second, the fact that myocyte size decreased post LVAD may have possibly affected other morphometric measurements that are based on the relative representation of other myocardial constituents. However, the structural changes of the non-myocyte myocardial constituents in our study were of such magnitude that even demonstration of relative increases could potentially have significant functional myocardial consequences. While the variable duration of mechanical support is another limitation of our study, it offers advantages as well, given that investigating the effects of LV unloading as a function of time is important and not well studied (27). We found that the tissue changes were similar in all the patients despite differences in duration of LV unloading. Moreover, it is possible that reactive fibrous response could have been present in myocardial tissue obtained at LVAD explantation, despite the fact that in an attempt to avoid this phenomenon we obtained our samples at least 1 cm from the LVAD inflow cannula. We believe that this is not very likely, though, as we verified that no morphologic findings suggestive of reactive inflammatory response were present in the studied myocardium. Finally, we studied the effects of unloading induced by pulsatile LVAD and this can be perceived as a limitation because, due to mainly engineering reasons, continuous flow, non pulsatile, devices are increasingly used. However, whether the prospect of LVAD induced reverse remodeling is better served by pulsatile (30–32), non-pulsatile or counterpulsation (3,33) devices, or by full versus partial (34) unloading, is unknown. Consequently, understanding the effects of pulsatile devices which provide profound unloading on remodeling becomes extremely important as the field is evolving. Our findings might be useful for future comparative investigations of various types and degrees of mechanical unloading.

Conclusion

LVAD induced unloading of the failing human heart increased microvascular density and was accompanied by endothelial cell activation, increased fibrosis and no structural, ultrastructural or metabolic changes compatible with cardiomyocyte degeneration and atrophy. These clinical findings may guide future studies aimed at unloading-induced reverse remodeling of the failing human heart.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Revision of manuscript critically for important intellectual content: Jay W Mason, Technical assistance: Mathew A Movsesian, Divya Ratan Verma, Aubrey Chan, Janet Hansen.

This work was funded by grants from: NHLBI, NIAID, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, HA and Edna Benning Foundation, National Center for Research Resources Public Health Services research grant UL1-RR025764, and the Department of Defense (to D.Y.L). D.Y.L. is a Burroughs Wellcome Foundation Clinical Scientist in Translational Research and an Established Investigator of the AHA.

NIH NCRR grant that supports the CCTS UL1-RR025764 and C06-RR11234 (to A.G.K. and S.G.D.)

AHA #09CRP2050127 (to J.S.)

Deseret Foundation, Utah, #571 (to A.G.K. and S.G.D)

Abbreviations List

- CSA

cross section area

- HF

heart failure

- LVAD

Left ventricular assist device

- MHC-2

major histocompatibility complex class 2

- PAS

periodic acid Schiff

- PASD

periodic acid Schiff with diastase

Footnotes

No conflict of interest exist

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fang JC. Rise of the Machines -- Left Ventricular Assist Devices as Permanent Therapy for Advanced Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2009 Nov 17; doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0910394. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klotz S, Danser AHJ, Burkhoff D. Impact of left ventricular assist device (LVAD) support on the cardiac reverse remodeling process. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;97:479–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drakos SG, Terrovitis JV, Anastasiou-Nana MI, Nanas JN. Reverse remodeling during long-term mechanical unloading of the left ventricle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:231–42. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz AM. Maladaptive growth in the failing heart: the cardiomyopathy of overload. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2002;16:245–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1020604623427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soppa GK, Barton PJ, Terracciano CM, Yacoub MH. Left ventricular assist device-induced molecular changes in the failing myocardium. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008;23:206–18. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3282fc7010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klotz S, Foronjy RF, Dickstein ML, et al. Mechanical unloading during left ventricular assist device support increases left ventricular collagen cross-linking and myocardial stiffness. Circulation. 2005;112:364–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.515106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:952–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Towbin JA. Scarring in the heart--a reversible phenomenon? N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1767–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr075397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho J, Parwani AV, Jukic DM, et al. Use of whole slide imaging in surgical pathology quality assurance: design and pilot validation studies. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:322–31. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pots SJ. Angiogenesis measurement using digital pathology. Lab Medicine. 2008;39:265–271. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond EH, Menlove RL, Anderson JL. Predictive value of immunofluorescence and electron microscopic evaluation of endomyocardial biopsies in the diagnosis and prognosis of myocarditis and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 1987;114:1055–65. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou AL, Egginton S, Brown MD, Hudlicka O. Capillary growth in overloaded, hypertrophic adult rat skeletal muscle: an ultrastructural study. Anat Rec. 1998;252:49–63. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199809)252:1<49::AID-AR6>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalluri R. EMT: when epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1417–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI39675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rakusan K, Heron MI, Kolar F, Korecky B. Transplantation-induced atrophy of normal and hypertrophic rat hearts: effect on cardiac myocytes and capillaries. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:1045–54. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf C, Cai WJ, Vosschulte R, et al. Vascular remodeling and altered protein expression during growth of coronary collateral arteries. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:2291–305. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitehead KJ, Chan AC, Navankasattusas S, et al. The cerebral cavernous malformation signaling pathway promotes vascular integrity via Rho GTPases. Nat Med. 2009;15:177–84. doi: 10.1038/nm.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones CA, London NR, Chen H, et al. Robo4 stabilizes the vascular network by inhibiting pathologic angiogenesis and endothelial hyperpermeability. Nat Med. 2008;14:448–53. doi: 10.1038/nm1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson BD, Li M, Park KW, et al. Netrins promote developmental and therapeutic angiogenesis. Science. 2006;313:640–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1124704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall JL, Grindle S, Han X, et al. Genomic profiling of the human heart before and after mechanical support with a ventricular assist device reveals alterations in vascular signaling networks. Physiol Genomics. 2004;17:283–91. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00004.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:389–95. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tansley P, Yacoub M, Rimoldi O, et al. Effect of left ventricular assist device combination therapy on myocardial blood flow in patients with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:1283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xydas S, Rosen RS, Pinney S, et al. Reduced myocardial blood flow during left ventricular assist device support: a possible cause of premature bypass graft closure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1976–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wohlschlaeger J, Schmitz KJ, Schmid C, et al. Reverse remodeling following insertion of left ventricular assist devices (LVAD): a review of the morphological and molecular changes. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:376–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virmani R, Burke A, Farb A, Atkinson JB. Cardiovascular Pathology. Saunders Company; 2001. Cardiomyopathy; pp. 179–230. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klotz S, Burkhoff D, Garrelds IM, Boomsma F, Danser AH. The impact of left ventricular assist device-induced left ventricular unloading on the myocardial renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: therapeutic consequences? Eur Heart J. 2009;30:805–12. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGowan BS, Scott CB, Mu A, et al. Unloading-induced remodeling in the normal and hypertrophic left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H2061–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00873.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oriyanhan W, Tsuneyoshi H, Nishina T, et al. Determination of optimal duration of mechanical unloading for failing hearts to achieve bridge to recovery in a rat heterotopic heart transplantation model. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNulty PH, Liu WX, Luba MC, et al. Effect of nonworking heterotopic transplantation on rat heart glycogen metabolism. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:E48–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.268.1.E48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajabi M, Kassiotis C, Razeghi P, Taegtmeyer H. Return to the fetal gene program protects the stressed heart: a strong hypothesis. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12:331–43. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maybaum S, Mancini D, Xydas S, et al. Cardiac improvement during mechanical circulatory support: a prospective multicenter study of the LVAD Working Group. Circulation. 2007;115:2497–505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.633180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dandel M, Weng Y, Siniawski H, et al. Prediction of cardiac stability after weaning from left ventricular assist devices in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2008;118:S94–105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.755983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birks EJ, Tansley PD, Hardy J, et al. Left ventricular assist device and drug therapy for the reversal of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1873–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drakos SG, Charitos CE, Ntalianis A, et al. Comparison of pulsatile with nonpulsatile mechanical support in a porcine model of profound cardiogenic shock. ASAIO J. 2005;51:26–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000150323.62708.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyns B, Klotz S, Simon A, et al. Proof of concept: hemodynamic response to long-term partial ventricular support with the synergy pocket micro-pump. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.