Abstract

Background

The use of areola-sparing (AS) or nipple-areola-sparing (NAS) mastectomy for the treatment or risk reduction of breast cancer has been the subject of increasing dialogue in the surgical literature over the past decade. We report the initial experience of a large community hospital with AS and NAS mastectomies for both breast cancer treatment and risk reduction.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed of patients undergoing either AS or NAS mastectomies from November 2004 through September 2009. Data collected included patient sex, age, family history, cancer type and stage, operative surgical details, complications, adjuvant therapies, and follow-up.

Results

Forty-three patients underwent 60 AS and NAS mastectomies. Forty-two patients were female and one was male. The average age was 48.7 years (range, 28–76 years). Forty mastectomies were for breast cancer treatment, and 20 were prophylactic mastectomies. The types of cancers treated were as follows: invasive ductal (n = 19), invasive lobular (n = 5), ductal carcinoma-in situ (n = 15), and malignant phyllodes (n = 1). Forty-seven mastectomies (78.3%) were performed by inframammary incisions. All patients underwent immediate reconstruction with either tissue expanders or permanent implants. There was a 5.0% incidence of full-thickness skin, areola, or nipple tissue loss. The average follow-up of the series was 18.5 months (range, 6–62 months). One patient developed Paget’s disease of the areola 34 months after an AS mastectomy (recurrence rate, 2.3%). There were no other instances of local recurrence.

Conclusions

AS and NAS mastectomies can be safely performed in the community hospital setting with low complication rates and good short-term results.

The surgical treatment of breast cancer over the past century has evolved from extensive disfiguring procedures to less invasive and cosmetically acceptable ones. The development of an oncoplastic approach to patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer means giving more consideration to the cosmetic (“plastic”) outcomes as well as maximizing oncologic (“onco”) safety. As the evolutionary process has continued, it is not surprising that one of the long-held dogmas of mastectomy surgery (sacrifice of the nipple-areola complex, NAC) would be challenged as necessary for all women undergoing mastectomy.

The use of areola-sparing (AS) and nipple-areola-sparing (NAS) mastectomy for the treatment or risk reduction of breast cancer has been the subject of increasing dialogue in the surgery literature over the past few decades.1–18 The primary concerns raised about the preservation of the areola and nipple are: (1) missing occult cancers in the nipple and/or areola; (2) having an increased risk of subsequent new or recurrent cancers in the retained NAC; and (3) partial or complete necrosis of the NAC.

Most reports on nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) have come from academic medical centers. Yet in the United States, approximately 85% of cancer care is delivered at the community level.19,20 If there is to be real traction for NSM to gain wider acceptance, then the adoption of this technique at the community level of cancer care would be important. Because most breast cancer care is at the community level, this setting is a rich source of short- and long-term data of patients undergoing NSMs. The goal of this study was to determine the feasibility of performing AS or NAS mastectomies, with immediate first-stage reconstructions, in the community setting.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board authorization, we retrospectively reviewed the charts of 43 patients who underwent either AS or NAS mastectomies from November 2004 through September 2009. The following patient data was collected: sex, age, family history, medical history, cancer type and stage, operative surgical details, complications, adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies, and follow-up.

Preoperatively, all patients underwent digital mammograms, high-resolution breast ultrasound, and breast magnetic resonance imaging. All cases were presented to a weekly preoperative multidisciplinary breast conference. No patients with clinical or imaging evidence of NAC involvement by their cancers or with locally advanced or inflammatory breast cancer were considered for the AS or NAS mastectomy. In addition, patients with lymph node involvement, those undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and those needing postoperative radiotherapy were considered for AS or NAS mastectomy.

The choice of mastectomy for cancer treatment was driven by patient choice, extent of cancer in the breast, and multicentric disease. All mastectomies in this series were performed by one surgeon (J.K.H.), and 85% of the reconstructions were performed by one plastic surgeon (A.H.S.).

Surgical Technique

An AS or NAS mastectomy is a skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) with preservation of the areola or nipple and areola, respectively. Our current technique is to remove the breast tissue by means of two incisions, one in the axilla and the other in the inframammary fold. The axillary incision is used for two aspects of the procedure. The first is the sentinel lymph node biopsy and/or axillary lymph node dissection, and the second is the dissection of the axillary tail and upper third of the breast. The breast is dissected off the pectoralis fascia in the upper third connecting with the same dissection from the inframammary fold. The dissection of the axillary tail is along the anterior mammary fascia medially, centrally, and caudally and assures that the entire axillary tail is resected.

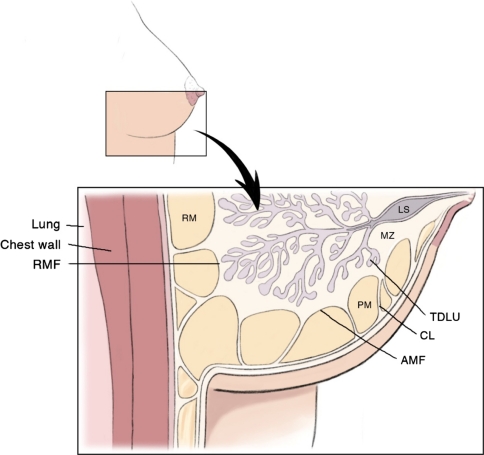

In the inframammary fold, a 12- to 14-cm incision is used. The initial maneuver from the inframammary fold is to free the breast from the pectoralis fascia. After this, the anterior mammary fascia is identified (Fig. 1) and the dissection is carried along this plane dividing the individual Cooper’s ligaments with scissors under the dermis (Fig. 1). This dissection preserves most of the subcutaneous fat layer, which in turn preserves the subdermal and subcutaneous fat blood vessels. No tumescent injections are used to facilitate the dissection.

Fig. 1.

Artist drawing depicting the anterior mammary fascia (AMF), retromammary fascia (RMF), Cooper’s ligaments (CL), and terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU). Also depicted is the premammary (PM) or subcutaneous fat zone. The retromammary zone (RM) is deep to the glandular tissue. The mammary zone (MZ) contains central ducts and most of the peripheral ducts and lobules. The lactiferous sinus (LS) is the dilated end of a lobar duct. (Reproduced with permission from Kuerer HM, ed. Breast Surgical Oncology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2010)

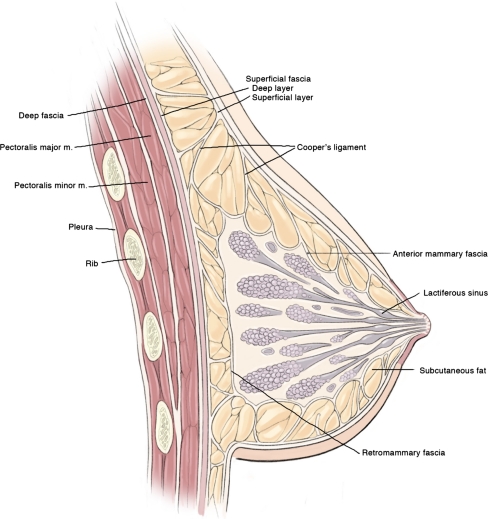

In the area of the cancer, the subcutaneous fat is thinned to the level of the superficial fascia under the dermis (Fig. 2). In some instances, all subcutaneous fat and the superficial fascia down to the dermis are excised, and when the cancer involves the anterior mammary fascia, the subdermal dissection is used. If there is extension of the cancer through the anterior mammary fascia into the subcutaneous fat, the overlying skin is excised. Intraoperative high-resolution ultrasound is used with invasive cancers to mark the skin in the area of the tumor.

Fig. 2.

Artist drawing of the cross-sectional anatomy of the breast showing important landmarks. (Reproduced with permission from Kuerer HM, ed. Breast Surgical Oncology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2010)

The subcutaneous fat layer of the breast disappears under the NAC. If breast tissue is found adherent to the underside of the areola, then it is dissected free. The base of the nipple is divided sharply, and the area where the base of the nipple is divided is marked with a short silk suture on the mastectomy specimen. In all cases, the nipple papilla is cored out or a deep sample of the nipple base is taken during biopsy. No breast tissue is left under the areola and nipple. Biopsy samples of the nipple base are evaluated with permanent histology, not via frozen sections.

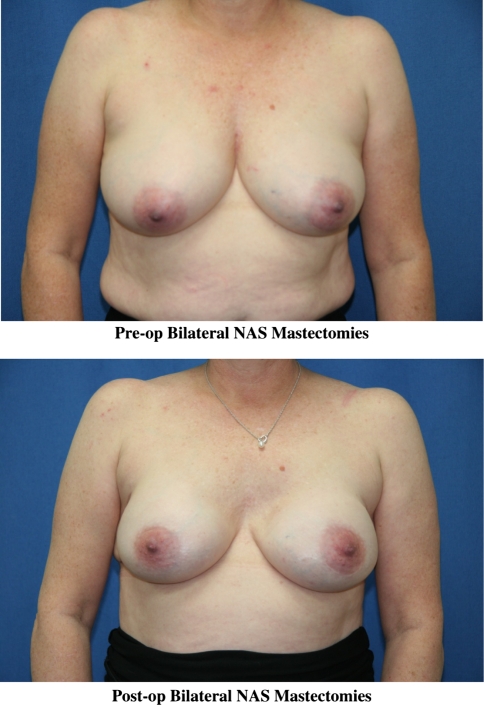

After the completion of the mastectomy and appropriate lymph node procedures, all patients underwent reconstruction with the placement of either a tissue expander or a permanent implant. Figure 3 shows the pre- and postoperative photos of a patient who underwent bilateral NAS mastectomies.

Fig. 3.

Pre- and postoperative photos of a 54-year-old patient who underwent bilateral nipple-areola-sparing mastectomies via inframammary and axillary incisions

Results

Forty-three patients (42 women, 1 man) underwent 60 AS (n = 17) or NAS (n = 43) mastectomies. Forty mastectomies were performed for cancer treatment, and 20 mastectomies were prophylactic. The average patient age was 48.7 years (range, 28–76 years). Eighteen (42%) of 43 patients had a family history for breast cancer, including 6 patients who were BRCA1/2 gene positive. Patient medical histories included existing heart disease (n = 2), hypertension (n = 7), diabetes mellitus (n = 4), history of stroke (n = 1), and smoking (n = 4).

The types of breast cancers treated were 19 invasive ductal carcinomas, 15 ductal carcinoma-in situ, 5 invasive lobular carcinomas, and 1 malignant phyllodes tumor. A summary of the pathology grades and tumor sizes is listed in Table 1. The final pathologic stages of our patients are depicted in Table 2. No patient had positive nipple biopsy findings. Of the 6 patients who were BRCA1/2 gene positive, 1 patient had bilateral prophylactic NAS mastectomies, whereas the other 5 patients had subsequent prophylactic AS or NAS mastectomies after their initial mastectomies for their primary cancers.

Table 1.

Pathology

| Disease | HG | IG | LG | Average size (cm) | Size range (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDC | 10 | 7 | 2 | 2.4 | 1.0–5.0 |

| ILC | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3.3 | 1.0–7.5 |

| DCIS | 6 | 8 | 1 | 1.9 | 1.0–4.5 |

HG high grade, IG intermediate grade, LG low grade, IDC invasive ductal carcinoma, ILC invasive lobular carcinoma, DCIS ductal carcinoma-in situ

Table 2.

AJCC cancer stage

| AJCC stage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| No. of patients | 14 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 1 |

AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer

Tumor markers were determined on all cancers except for the one patient who had a malignant phyllodes tumor. Twenty-one patients were estrogen receptor and/or progesterone receptor positive, 9 were HER-2/neu positive, and 6 were triple negative. Eight patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 13 underwent adjuvant chemotherapy, 21 received adjuvant antiestrogen therapy, and 11 received postoperative radiotherapy to their mastectomy sites, axillae, and supraclavicular regions.

Forty-seven mastectomies (78.3%) were performed by inframammary incisions. Eleven radial incisions and two nonradial incisions were used for the remaining 21.7% of the mastectomies. These 13 patients had previously undergone either partial mastectomies or breast biopsies, or they had an indication to achieve breast symmetry. Superficial skin, areola, and nipple slough occurred in 6 (10%) of our 60 mastectomies. All of these healed in 2 weeks with only slight depigmentation of the nipple or areola. The more serious complication of full-thickness loss of skin, nipple, or the NAC occurred in 3 patients (5%). The patient with the nipple-areola loss had undergone a 6 × 3 cm wide area of subdermal fat thinning adjacent to the areola because of tumor proximity. The nipple areolar eschar was excised, the expander was removed, and the breast was reconstructed in stages at a later date. The second patient with nipple necrosis healed spontaneously in 2 months; a flat scar was left. The third patient who had the mastopexy as part of the NAS mastectomy had diabetes. The ischemic corners of the medial and the lateral mastopexy flaps were debrided, and the wound was allowed to heal in secondarily for a delayed implant exchange. Other complications included postoperative bleeding (n = 1) and infection (n = 2). The two patients with infected tissue expanders and the one with necrosis of the NAC required unplanned removal of their expanders. No complications occurred in the 11 patients who underwent postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy.

The average follow-up time of the series was 18.5 months (range, 6–62 months). One patient (2.3%) developed a recurrent cancer, which was Paget’s disease of the areola, 34 months after an AS mastectomy. This was treated with resection of the areola. At pathologic review, the nipple was found to be not involved with ductal carcinoma-in situ at the time of her AS mastectomy. There have been no other instances of local recurrences.

Discussion

The concept of the NSM was popularized by Freeman in the 1960 s and 1970s.21 The procedure was referred to as a subcutaneous mastectomy. Breast tissue was left along the undersurface of the NAC to protect the blood supply to the nipple and areola. Many patients underwent these procedures at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, for approximately 20 years. Subsequently, Hartmann et al. published the follow-up data on these patients from the Mayo Clinic and found that prophylactic subcutaneous mastectomy did have a protective benefit by reducing the risk of breast cancer in both high-risk and moderate-risk groups by 81–94%.22 In their later study, which was based on the same patient population, a similar risk reduction was found in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations.23 However, the subcutaneous mastectomy fell out of favor in the United States.

The use of NSM for the treatment of breast cancer grew in the 1970 s and 1980s.24,25 In 2003, Gerber, Krause, and colleagues from Germany reported their experience with NSM.1 At 59 months, there were 6 recurrences (5.4%) in the 112 NSMs and 11 recurrences (8.2%) among the 134 women who had the NAC removed with their mastectomies.1 After the report by Gerber et al., other single institutions have reported their experience with NSMs.2–18

A review article by Voltura et al. found local recurrence rates with NSM showed an equivalency to SSM.7 They thought that patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy were acceptable candidates for NSM. They did not core out the nipple. Their selection criteria included tumors ≤4.5 cm that were also ≥2.5 cm from the edge of the areola. They excluded patients with bloody nipple discharge, inflammatory breast cancer, or tumor involvement of the NAC.

Garcia-Etienne et al. found that in properly selected cases local control after NSM is consistent with that of total standard mastectomy and SSM.8 They stated an opinion that local failure is a manifestation of tumor biology rather than preservation of the NAC. They reviewed 1826 NSMs performed for breast cancer treatment published in the recent literature and found only three local recurrences (0.16%) within the NAC.6,14,16 They thought that preoperative evaluation for NSM should include complete imaging studies, preferably breast magnetic resonance imaging. They included in their selection criteria tumor size of up to 5 cm and a tumor to nipple distance of ≥2 cm.

Rusby et al. have published the most recent review of NSM in the literature.12 They also found recurrence rates of <5% in properly selected patients undergoing NSM for breast cancer treatment. The incidence of cancer in the retained nipple after risk-reducing mastectomy is <1%. Nipple necrosis rates were 8 and 16% for total and partial necrosis, respectively. They also reviewed some of the literature on terminal ductal lobular units in the nipple. The incidence was reported to be between 9% and 17%, with most of the terminal ductal lobular units at the base of the nipple papilla.26 They cautioned against fixed-volume reconstructions after NSM because of a higher incidence of NAC necrosis.

The major limitations of our series are the limited numbers of cases and short follow-up. However, comparing our initial series of 43 patients with 60 AS or NAS mastectomies with the published literature showed many similarities. We have treated the full spectrum of breast cancer, excluding patients with locally advanced or inflammatory tumors as well as those involving the NAC.

Only 2 patients (3.3%) had full-thickness nipple/areola loss because we saved the NAC. Our results compared favorably with those of the published literature on NAC loss.7,8,12

The 11 patients who underwent postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy had no complications. This experience parallels our outcomes with SSM who had first-stage reconstructions with tissue expanders. With both NSM and SSM, we replace the tissue expanders with either saline or silicone implants 4 months after the completion of radiotherapy.

In our series, we have had only one case of local recurrence of breast cancer. The recurrence was Paget’s disease of the areola diagnosed 34 months after an AS mastectomy. The patient was treated with resection of her areola and has had no further recurrence of cancer 13 months later. Our short-term recurrence rate compares favorably with similar series in the literature.2,7

Our initial experience with AS or NAS mastectomies in the community setting has taught us several things. First, the performance of NSM can be effectively accomplished in the community setting. This procedure requires a team effort. Determining suitability for NSM is a joint process between the breast and the plastic surgeon. Patients with moderate to marked ptosis were not excluded because we perform a modified mastopexy to correct the ptosis as part of the NSM mastectomy.

In our series, inclusion criteria for NSM are nearly the same as those for SSM (multicentric disease, extent of disease too large for breast conservation, and patient choice). Exclusion criteria for NSM in our series included inflammatory breast cancer, involvement of the NAC, and locally advanced breast cancers.

The high viability rate of the NAC is likely the result of three factors. First, we use primarily inframammary incisions that spare the medial and lateral vessels supplying the skin of the breast. Second, the subcutaneous fat plane of the breast is preserved, which then preserves the microcirculation of the breast skin and areola. The subcutaneous fat layer is only thinned in the area of the cancer. Third, most of the reconstructions were performed with tissue expanders and not fixed-volume implants or autologous flaps, which create increased pressure in the subcutaneous space.

In conclusion, NSM can be safely performed in the community hospital setting with low complication rates and good short-term results. The inframammary approach for NSM in our hands has been a safe and reliable procedure that does not adversely affect the viability of the NAC. In addition, our experience with the inframammary approach results in less visible scars, which we think provides better aesthetic results.

We have adopted the following indications and contraindications for NSM: indications are candidates for SSM and patient choice, and contraindications are involvement of the NAC, and presence of inflammatory and locally advanced breast cancers.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Gerber B, Krause A, Reimer T, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple-areola complex and autologous reconstruction is an oncologically safe procedure. Ann Surg. 2003;238:120–127. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowe JP, Kim JA, Yetman R, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: technique and results of 54 procedures. Arch Surg. 2004;139:148–150. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petit JY, Veronesi U, Orecchia R, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in association with intra operative radiotherapy (ELIOT): a new type of mastectomy for breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;96:47–51. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stolier AJ, Sullivan SK, Dellacroce FJ. Technical considerations in nipple-sparing mastectomy: 82 consecutive cases without necrosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1341–1347. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijayanayagam A, Kumar AS, Foster RD, Esserman LJ. Optimizing the total skin-sparing mastectomy. Arch Surg. 2008;143:38–45. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerber B, Krause A, Dieterich M, Kundt G, Reimer T. The oncological safety of skin sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple-areola complex and autologous reconstruction: an extended follow-up study. Ann Surg. 2009;249:461–468. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819a044f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voltura AM, Tsangaris TN, Rosson GD, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: critical assessment of 51 procedures and implications for selection criteria. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3396–3401. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Etienne CA, Cody HS, III, Disa JJ, Cordeiro P, Sacchini V. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: initial experience at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and a comprehensive review of literature. Breast J. 2009;15:440–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garwood ER, Moore D, Ewing C, et al. Total skin-sparing mastectomy: complications and local recurrence rates in 2 cohorts of patients. Ann Surg. 2009;249:26–32. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e41a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HJ, Park EH, Lim WS, et al. Nipple areola skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap reconstruction is an oncologically safe procedure: a single center study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:493–498. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c5dc4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spear SL, Hannan CM, Willey SC, Cocilovo C. Nipple-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1665–1673. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a64d94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rusby JE, Smith BL, Gui GP. Nipple-sparing mastectomy. Br J Surg. 2010;97:305–316. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benediktsson KP, Perbeck L. Survival in breast cancer after nipple-sparing subcutaneous mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with implants: a prospective trial with 13 years median follow-up in 216 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caruso F, Ferrara M, Castiglione G, et al. Nipple sparing subcutaneous mastectomy: sixty-six months follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:937–940. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CM, Disa JJ, Sacchini V, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy and immediate tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1772–1780. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aa0fb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowe JP, Patrick RJ, Yetman RJ, Djohan R. Nipple-sparing mastectomy update: one hundred forty-nine procedures and clinical outcomes. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1106–1110. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djohan R, Gage E, Gatherwright J, et al. Patient satisfaction following nipple-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction: an 8-year outcome study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:818–829. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ccdaa4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziogas D, Roukos DH, Zografos GC. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: overcoming oncological outcomes challenges. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:323–324. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green LA, Fryer GE, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:2021–2025. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106283442611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrelli NJ. A community cancer center program: getting to the next level. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman BS. Subcutaneous mastectomy for benign breast lesions with immediate or delayed prosthetic replacement. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1962;30:676–682. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartmann LC, Schaid DJ, Woods JE, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:77–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartmann LC, Degnim A, Schaid DJ. Prophylactic mastectomy for BRCA1/2. carriers: progress and more questions. J Clin Oncol. 22:6:981–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kissin MW, Kark AE. Nipple preservation during mastectomy. Br J Surg. 1987;74:58–61. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800740118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bishop CC, Singh S, Nash AG. Mastectomy and breast reconstruction preserving the nipple. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72:87–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stolier AJ, Wang J. Terminal duct lobular units are scarce in the nipple: implications for prophylactic nipple-sparing mastectomy: terminal duct lobular units in the nipple. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:438–442. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9568-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]