Abstract

Infections due to Aspergillus species cause significant morbidity and mortality. Most are attributed to Aspergillus fumigatus, followed by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus terreus. Aspergillus niger is a mould that is rarely reported as a cause of pneumonia. A 72-year-old female with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and temporal arteritis being treated with steroids long term presented with haemoptysis and pleuritic chest pain. Chest radiography revealed areas of heterogeneous consolidation with cavitation in the right upper lobe of the lung. Induced bacterial sputum cultures, and acid-fast smears and cultures were negative. Fungal sputum cultures grew A. niger. The patient clinically improved on a combination therapy of empiric antibacterials and voriconazole, followed by voriconazole monotherapy. After 4 weeks of voriconazole therapy, however, repeat chest computed tomography scanning showed a significant progression of the infection and near-complete necrosis of the right upper lobe of the lung. Serum voriconazole levels were low–normal (1.0 μg ml−1, normal range for the assay 0.5–6.0 μg ml−1). A. niger was again recovered from bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. A right upper lobectomy was performed, and lung tissue cultures grew A. niger. Furthermore, the lung histopathology showed acute and organizing pneumonia, fungal hyphae and oxalate crystallosis, confirming the diagnosis of invasive A. niger infection. A. niger, unlike A. fumigatus and A. flavus, is less commonly considered a cause of invasive aspergillosis (IA). The finding of calcium oxalate crystals in histopathology specimens is classic for A. niger infection and can be helpful in making a diagnosis even in the absence of conidia. Therapeutic drug monitoring may be useful in optimizing the treatment of IA given the wide variations in the oral bioavailability of voriconazole.

Introduction

Aspergillus niger is a mould that is rarely reported as a cause of pneumonia. Here we report a case of necrotizing A. niger fungal pneumonia that did not respond to voriconazole in a patient on long-term steroid treatment.

Case report

A 72-year-old woman presented with 3 weeks of a non-productive cough and pleuritic chest pain. Her history was notable for stage II chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), not requiring systemic steroids or home oxygen therapy, and a recent diagnosis of biopsy-proven temporal arteritis. The latter was diagnosed 9 months previously and she had been on tapering dose of dexamethasone (from 9 to 2.5 mg on presentation). She had seen her primary care physician 2 weeks prior to presentation and was given a course of moxifloxacin followed by azithromycin for community-acquired pneumonia, but her symptoms persisted.

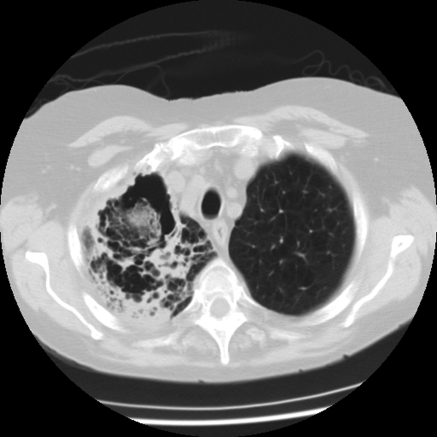

The patient was afebrile with an oxygen saturation of 96 % on 2 l oxygen min−1 via nasal canula and a respiratory rate of 18 breaths min−1. A pulmonary examination showed a prolonged expiratory phase with crackles in the right upper hemithorax. Laboratory results were notable for a leukocytosis of 2.11×1010 leukocytes l−1. A chest radiograph showed a right upper lobe heterogeneous opacity. She was started on antibiotics for health-care-associated pneumonia and placed in special respiratory isolation given an initial concern for tuberculosis. A chest computed tomography scan (CT) revealed heterogeneous consolidation in the right upper lobe with cavitation (Fig. 1). Voriconazole was started empirically for fungal infection given the cavitation seen on the CT scan and the patient's immunocompromised status. A bacterial sputum culture showed oropharyngeal flora and an unidentified mould; sputum fungal culture was sent for testing and grew A. niger. Three acid-fast bacilli smears and cultures were negative. Bronchoscopy found diffusely erythematous and friable mucosa, blood and debris present in the right upper lobe of the lungs; biopsies for histopathology were not done due to oxygen desaturations during the procedure. Cytology testing and cultures from the bronchoalveolar lavage were negative.

Fig. 1.

Chest CT scan showing heterogeneous consolidation in the right upper lobe of the lungs with cavitation.

Surgical resection of the cavitary lesion was considered, but the patient refused surgical intervention. Her symptoms improved and her leukocytosis resolved with empiric antifungal and antibacterial therapy. The patient met criteria for probable invasive Aspergillus infection (De Pauw et al., 2008) and after consultation with the Thoracic Surgery, Infectious Disease, and Pulmonary teams of the Duke University Medical Center, the decision was made to treat her with 200 mg voriconazole orally twice daily. Follow-up in the Infectious Disease Clinic (Duke University Medical Center) and a repeat CT scan was planned for 4 weeks later.

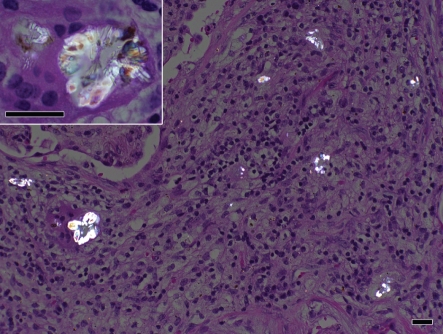

On her visit to the Infectious Disease Clinic 1 month later, the patient reported feeling better, with decreased cough. However, a CT scan demonstrated increasing cavitation and progression of the disease despite therapy with voriconazole. Serum voriconazole levels were low–normal [1.0 μg ml−1 (normal range for assay 0.5–6.0 μg ml−1)]. Bronchoscopy was again performed, with repeat cultures persistently growing A. niger. Bacterial cultures remained negative. With progression of the disease shown by radiography and persistently positive cultures, surgical intervention was reconsidered. The patient subsequently underwent right upper lobectomy. Surgical cultures grew A. niger. Pathology revealed acute and organizing pneumonia, stains consistent with fungal hyphae and oxalate crystallosis (Fig. 2), thus fulfilling the criteria for the diagnosis of proven invasive A. niger infection (De Pauw et al., 2008). The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course, and was discharged with pulmonary rehabilitation and continued voriconazole therapy.

Fig. 2.

Surgical pathology of specimens from right upper lobectomy of the lung, showing acute and organizing pneumonia and oxalate crystallosis consistent with A. niger infection. Bars, 25 μm.

Discussion

Infections due to Aspergillus species result in significant morbidity and mortality. Most infections are attributed to Aspergillus fumigatus (Table 1), followed by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus terreus. A. niger is less commonly reported as a cause of invasive disease. A. niger has been associated with otomycosis (Araiza et al., 2006), cutaneous infections (Loudon et al., 1996) and pulmonary disease. There are few reports of A. niger causing pneumonia. In three separate case reports, A. niger pulmonary infection was fatal; one patient had been on long-term steroid treatment for COPD (Wiggins et al., 1989), a second had a history of asbestos exposure and tuberculosis (Nakagawa et al., 1999) and a third had a history of Mycobacterium avium complex causing cavitary disease (Kimmerling et al., 1992). All had evidence of heavy calcium oxalate deposition on pathological examination. A review of COPD patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) found 3.6 % of cases were due to A. niger (Bulpa et al., 2007). In a case series of eight patients with invasive A. niger infection and haematological malignancies, three were on high-dose steroids, and seven were neutropenic. There was a 75 % mortality rate attributed to A. niger (6/8) (Fianchi et al., 2004).

Table 1.

Characteristics of A. niger versus A. fumigatus

A. fumigatus is a much more common cause of IPA compared to A. niger; this may be due to their differences in morphology.

| A. fumigatus | A. niger | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency in invasive infection | 66–90 % (Patterson et al., 2000). | 5 % (Patterson et al., 2000). |

| Voriconazole MIC90 | 0.25–2.0 μg ml−1 (Johnson & Kauffman, 2003). | 0.5–4.0 μg ml−1 (Johnson & Kauffman, 2003). |

| Size | 2–3.5 μm; small size allows entry into lower respiratory tract and more invasive pulmonary disease (Sutton et al., 1998). | 6–7 μm; large size allows easy uptake by host mucociliary system and more upper respiratory infections: otitis, tracheobronchitis (Xavier et al., 2008). |

| Temperature for growth | Thermophilic species (growth at 40 °C and above) allowing easier growth in human lungs (Araujo & Rodrigues, 2004). | Less thermotolerant, ideal temperature for growth is 30–34 °C, making germination difficult in human body temperature of at least 37 °C (Xavier et al., 2008). |

| pH for optimal growth | Prefers acidic environment but can tolerate growth through a broad range of pH, including slightly alkaline pH (Araujo & Rodrigues, 2004). | Acidophilic nature with maximal germination at pH of 4.5, limiting its growth; low pH allows oxalic acid production (Xavier et al., 2008). |

The diagnostic dilemma presented in this case was the determination of the aetiology of the patient's cavitary lung disease. The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesions is broad. Our patient was at risk for fungal infections, mycobacterial infections including Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other bacterial pathogens, given her long-term steroid use. The cause of our patient's necrotizing pneumonia was initially attributed to A. niger, as this was the only pathogen recovered from sputum samples. However, it can be difficult to distinguish between colonization and infection when Aspergillus is found in the lungs. Identifying Aspergillus in the lower respiratory tract was associated with invasive disease in a study of patients with haematological malignancies or those undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Perfect et al., 2001). However, among lung transplant recipients, recovery of Aspergillus rarely resulted in progression to overt infection (Mehrad et al., 2001). A review of COPD patients with IPA highlights the need to distinguish between colonization and infection, and suggests a diagnostic algorithm for these patients. Sputum cultures alone may not be helpful; out of 56 COPD patients with IPA, only 12 (21.4 %) had cultures positive for Aspergillus (Bulpa et al., 2007). Thus, serological tests (such as the galactomannan antigen assay) and radiography tests (with ‘halo sign’ and ‘air crescent sign’ on CT being highly suggestive of IPA) must often be combined with microbiological/histological data to establish a diagnosis of true infection. Conclusive culture data or histological evidence of IPA may necessitate bronchoscopy or lung biopsy.

A key feature in the diagnosis of A. niger infection is the presence of calcium oxalate crystals on pathological examination. Oxalic acid precipitates and forms crystals when produced via a fermentation process by A. niger. The association of calcium oxalate crystals with A. niger infection has been repeatedly demonstrated, and it has been suggested that even in the absence of visualized conidia, the presence of these crystals may indicate A. niger infection (Procop & Johnston, 1997). Both calcium oxalate crystals and numerous conidia were seen in our patient's pathological specimens, pointing to A. niger as the aetiological agent of our patient's cavitary lung lesions.

Treatment of invasive aspergillosis (IA) has evolved; one large, unblinded, randomized controlled trial of amphotericin B versus voriconazole demonstrated improved 12 week survival rates and decreased drug-related adverse events with voriconazole (Herbrecht et al., 2002). Voriconazole is thus considered the drug of choice for IA (Walsh et al., 2008). When our patient demonstrated significant progression of cavitation on her chest CT despite therapy with voriconazole, one possible explanation was azole resistance. In the USA, however, the resistance of Aspergillus to azoles is uncommon (Baddley et al., 2009), and therefore susceptibility testing of our patient's isolate was not performed. Another possible explanation for progressive disease was that subtherapeutic voriconazole levels were contributing to failure of therapy.

The role of therapeutic drug monitoring for voriconazole is controversial. Voriconazole exhibits nonlinear pharmacokinetics; it has been shown that there is great variability in the serum level among healthy hosts. The wide variation in serum levels is due to differences in the ability of hosts to metabolize voriconazole through the CYP450 enzyme (Bochud et al., 2008); specifically, polymorphisms in CYP2C19 have delineated ‘poor’ and ‘extensive’ metabolizers of voriconazole (Desta et al., 2002). Not only do levels vary, but the goal serum concentration for voriconazole is unknown. In one retrospective review of voriconazole level monitoring, a pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic breakpoint was observed around a concentration of 2.05 μg ml−1. Those with serum levels above this level responded favourably to treatment, while nearly half of those (44 %) with levels below 2.05 μg ml−1 had progression of disease (Smith et al., 2006). Our patient's serum voriconazole level was 1.0 μg ml−1, so it is possible that despite falling within the normal range for the assay (0.5–6.0 μg ml−1), the dose was not truly adequate. Guidelines on the treatment and management of IA recommend considering therapeutic drug monitoring in patients who have progressive infection despite presumed adequate dosing (Walsh et al., 2008). The protocol in the initial study of voriconazole included an intravenous loading dose (Herbrecht et al., 2002); as a result, current recommendations are for a loading dose to be given parenterally if possible, and if not, an oral loading dose is recommended (Walsh et al., 2008). Our patient did not receive a loading dose, and this may have contributed to inadequate serum levels. Ultimately, our patient required surgical intervention. IA is an uncommon surgical disease; most surgical series are small and composed of patients with either haematological malignancies or transplants (Baron et al., 1998; Danner et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 1995; Salerno et al., 1998). In this case, the major indications for surgery were the radiographical evidence of disease progression despite appropriate antifungal therapy and the continued need for immunosuppression. Regardless of underlying diagnoses, other indications for surgery in patients with IPA include haemoptysis, a critical anatomical location of cavitary lesions, and the presence of focal (and therefore resectable) lesions (Danner et al., 2008).

In conclusion, although IA is a well-recognized clinical entity, invasive disease caused by A. niger is less common when compared to A. fumigatus and other Aspergillus species, and diagnosis can be complicated by the need to distinguish colonization from infection. This case demonstrates the potentially aggressive nature of A. niger, the utility of calcium oxalosis in histopathological examinations, and the importance of monitoring serum voriconazole concentrations, especially in the setting of progressive disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant no. 5T32 AI007392 (A. K. Person) from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CT, computed tomography

IA, invasive aspergillosis

IPA, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

References

- Araiza, J., Canseco, P. & Bonifaz, A. (2006). Otomycosis: clinical and mycological study of 97 cases. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 127, 251–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, R. & Rodrigues, A. G. (2004). Variability of germinative potential among pathogenic species of Aspergillus. J Clin Microbiol 42, 4335–4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddley, J. W., Marr, K. A., Andes, D. R., Walsh, T. J., Kauffman, C. A., Kontoyiannis, D. P., Ito, J. I., Balajee, S. A., Pappas, P. G. & Moser, S. A. (2009). Patterns of susceptibility of Aspergillus isolates recovered from patients enrolled in the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network. J Clin Microbiol 47, 3271–3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron, O., Guillaumé, B., Moreau, P., Germaud, P., Despins, P., De Lajartre, A. Y. & Michaud, J. L. (1998). Aggressive surgical management in localized pulmonary mycotic and nonmycotic infections for neutropenic patients with acute leukemia: report of eighteen cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 115, 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochud, P. Y., Chien, J. W., Marr, K. A., Leisenring, W. M., Upton, A., Janer, M., Rodrigues, S. D., Li, S., Hansen, J. A. & other authors (2008). Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms and aspergillosis in stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 359, 1766–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulpa, P., Dive, A. & Sibille, Y. (2007). Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 30, 782–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danner, B. C., Didilis, V., Dorge, H., Mikroulis, D., Bougioukas, G. & Schondube, F. A. (2008). Surgical treatment of pulmonary aspergillosis/mycosis in immunocompromised patients. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 7, 771–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw, B., Walsh, T. J., Donnelly, J. P., Stevens, D. A., Edwards, J. E., Calandra, T., Pappas, P. G., Maertens, J., Lortholary, O. & other authors (2008). Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 46, 1813–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desta, Z., Zhao, X., Shin, J. G. & Flockhart, D. A. (2002). Clinical significance of the cytochrome P450 2C19 genetic polymorphism. Clin Pharmacokinet 41, 913–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fianchi, L., Picardi, M., Cudillo, L., Corvatta, L., Mele, L., Trape, G., Girmenia, C. & Pagano, L. (2004). Aspergillus niger infection in patients with haematological diseases: a report of eight cases. Mycoses 47, 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbrecht, R., Denning, D. W., Patterson, T. F., Bennett, J. E., Greene, R. E., Oestmann, J. W., Kern, W. V., Marr, K. A., Ribaud, P. & other authors (2002). Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med 347, 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L. B. & Kauffman, C. A. (2003). Voriconazole: a new triazole antifungal agent. Clin Infect Dis 36, 630–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerling, E. A., Fedrick, J. A. & Tenholder, M. F. (1992). Invasive Aspergillus niger with fatal pulmonary oxalosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 101, 870–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudon, K. W., Coke, A. P., Burnie, J. P., Shaw, A. J., Oppenheim, B. A. & Morris, C. Q. (1996). Kitchens as a source of Aspergillus niger infection. J Hosp Infect 32, 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrad, B., Paciocco, G., Martinez, F. J., Ojo, T. C., Iannettoni, M. D. & Lynch, J. P., III (2001). Spectrum of Aspergillus infection in lung transplant recipients: case series and review of the literature. Chest 119, 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, Y., Shimazu, K., Ebihara, M. & Nakagawa, K. (1999). Aspergillus niger pneumonia with fatal pulmonary oxalosis. J Infect Chemother 5, 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, T. F., Kirkpatrick, W. R., White, M., Hiemenz, J. W., Wingard, J. R., Dupont, B., Rinaldi, M. G., Stevens, D. A. & Graybill, J. R. for theI3 Aspergillus Study Group (2000). Invasive aspergillosis: disease spectrum, treatment practices, and outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore) 79, 250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect, J. R., Cox, G. M., Lee, J. Y., Kauffman, C. A., de Repentigny, L., Chapman, S. W., Morrison, V. A., Pappas, P., Hiemenz, J. W. & Stevens, D. A. (2001). The impact of culture isolation of Aspergillus species: a hospital-based survey of aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis 33, 1824–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procop, G. W. & Johnston, W. W. (1997). Diagnostic value of conidia associated with pulmonary oxalosis: evidence of an Aspergillus niger infection. Diagn Cytopathol 17, 292–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, L. A., Reed, E. C., Galbraith, T. A., Alonso, A., Moulton, A. L. & Fleming, W. H. (1995). Pulmonary resection for invasive Aspergillus infections in immunocompromised patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 109, 1182–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno, C. T., Ouyang, D. W., Pederson, T. S., Larson, D. M., Shake, J. P., Johnson, E. M. & Maddaus, M. A. (1998). Surgical therapy for pulmonary aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients. Ann Thorac Surg 65, 1415–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J., Safdar, N., Knasinski, V., Simmons, W., Bhavnani, S. M., Ambrose, P. G. & Andes, D. (2006). Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50, 1570–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, D. A., Fothergill, A. W. & Rinaldi, M. G. (editors) (1998). Guide to Clinically Significant Fungi, 1st edn. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins.

- Walsh, T. J., Anaissie, E. J., Denning, D. W., Herbrecht, R., Kontoyiannis, D. P., Marr, K. A., Morrison, V. A., Segal, B. H., Steinbach, W. J. & other authors (2008). Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 46, 327–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, J., Clark, T. J. & Corrin, B. (1989). Chronic necrotising pneumonia caused by Aspergillus niger. Thorax 44, 440–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, M. O., Sales, M. P. U., Camargo, J. J. P., Pasqualotto, A. C. & Severo, L. C. (2008). Aspergillus niger causing tracheobronchitis and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a lung transplant recipient: case report. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 41, 200–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]