Abstract

Frontal sinus fracture represents 5 to 12% of all maxillofacial fractures. Because of the anatomic position of the frontal sinus and the enormous amount of force required to create a fracture in this area, these injuries are often devastating and associated with other trauma. Associated injuries include skull base, intracranial, ophthalmologic, and maxillofacial. Complications should be categorized to address these four areas as well as the skin–soft tissue envelope, muscle, and bone. Other variables that should be examined are age of the patient, gender, mechanism of injury, fracture pattern, method of repair, and associated injuries. Management of frontal sinus fractures is so controversial that the indications, timing, method of repair, and surveillance remain disputable among several surgical specialties. The one universal truth that is agreed upon is that all patients undergoing reconstructive surgery of the frontal sinus have a lifelong risk for delayed complications. It is hoped that when patients do experience the first symptoms of a complication, they seek immediate medical attention and avoid potentially life-threatening situations and the need for crippling or disfiguring surgery. The best way to facilitate this is through long-term follow-up and routine surveillance.

Keywords: Complication, frontal, sinus, fracture, chronic, acute

Frontal sinus fractures are usually caused by anterior blunt force trauma. The majority of these injuries are secondary to motor vehicle accidents (Fig. 1).1,2,3 With the advent of mandatory seatbelt laws and airbags, we have seen a decrease in frontal sinus fractures by motor vehicle accidents but an increase in fractures by interpersonal violence (blunt and penetrating), sports injuries, falls, and falling objects.3,4,5 The choice of treatment is usually dictated by the site and extent of the damage. Concomitant injuries also play a role in treatment selection as well as timing of repair. This is important because inadequate or delayed treatment can lead to immediate and/or long-term complications.6,7

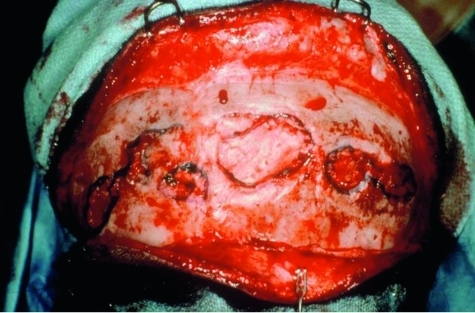

Figure 1.

Photograph of patient involved in a motor vehicle accident with open, linear, minimally displaced anterior table frontal sinus fracture. This is the usual presentation for an open frontal sinus fracture with the usual orbital, maxillofacial, neurologic, and ophthalmologic sequelae.

Disruption of the nasofrontal ostia or ducts is an important factor in the development of immediate and delayed complications after frontal sinus fractures (Fig. 2).8 Combined fractures of the anterior and posterior table are almost always accompanied by injuries to the nasofrontal orifices.4,5,8 Severity of the injuries is variable but can be predicted from the sinus wall fracture pattern and the mechanism of injury.4,8 High-resolution computed tomography (CT) scanning as well as image-guided endoscopy can give sufficient information to predict a disruption of the drainage system, but there is nothing as good as direct visualization of the nasofrontal ostia.2,9,10 Functional status can be estimated with fluorescein endoscopy; however, this may not always be accurate.3,10,11,12 Successful management of frontal sinus fractures depends on correct diagnosis of structural pathology, which may lead to inflammatory or infectious complications. When in doubt, it is better to separate the anterior skull base from the nasal cavity. We believe this is best accomplished with vascularized tissue (Fig. 3).2,13,14

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photograph of anterior and posterior wall frontal sinus fractures with no CSF leak and destruction of the nasofrontal ostia (drainage system).

Figure 3.

Placement of a well-vascularized pericranial flap for separation of the anterior skull base from the nasal cavity. The ducts are plugged with temporalis muscle after thorough mucosal removal, and the pericranial flap is tucked in and secured with fibrin glue.

Posttraumatic infectious complications of the frontal sinus and anterior skull base occur more frequently after multiple fractures than after isolated fractures. The highest incidence is found with open fractures associated with penetrating trauma due to the presence of foreign bodies. There is also a higher rate of infection with concomitant maxillofacial injuries possibly due to greater bone and mucosal destruction.15,16 Although injuries to the frontal sinus are a reasonably common traumatic event encountered by the reconstructive surgeon, definitive indications for open exploration and the optimum method for treating the residual sinus cavity remain controversial.14,17

SKULL-BASE COMPLICATIONS

The most common skull-base complication encountered with frontal sinus fractures is mucocele (Fig. 4). This is usually related to injury of the nasofrontal ostia (ducts) that is undiagnosed or poorly treated. The frontal sinus mucosa can be tenacious and if left behind after a frontal sinus fracture repair can manifest as a mucocele many years later (Fig. 5).18,19 Mucopyocele is simply an infected mucocele and should be included in this category.

Figure 4.

Mucocele eroding through anterior table of old frontal sinus fracture patient. This particular case is 8 years after original treatment (reconstruction of anterior wall). This again demonstrates the need for constant follow-up and periodic imaging studies.

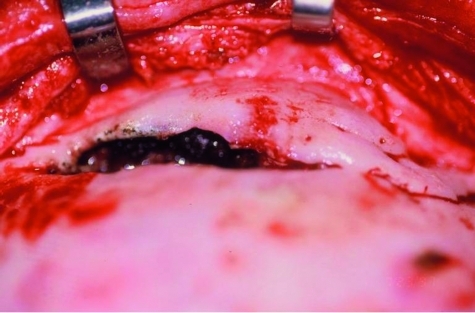

Figure 5.

The frontal sinus mucosa is tenacious. The mucosa looks black in this frontal sinus fracture with extension into the orbit. It is ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium with unidirectional sweeping motion toward the nasofrontal ostia. The mucosa is densely adherent to the diplopic veins via the foramina of Breschet.

Prevention is the best treatment, and fastidious removal of mucosa and/or a patent drainage system is necessary to create a safe sinus. The most serious skull-base complication is cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) leak.20 Most of the time this is transient, but it may be persistent and require cranialization and dural repair (Fig. 6).21,22 The two areas most commonly affected are the cribriform plate where the dura is densely adherent and the foveae ethmoidalis where the bone is thinnest and sometimes dehiscent.23 Devastating consequences of unrecognized or untreated CSF leak include meningitis, encephalitis, and epidural and/or subdural abscess. Proper imaging with high-resolution CT scanning, cisternography, fluorescein endoscopy, and a high index of suspicion is often necessary to make this diagnosis. Subtle CSF rhinorrhea may be the only presenting symptom. Image-guided endoscopy may be helpful as well as fluid collection testing for β-2-transferrin.24

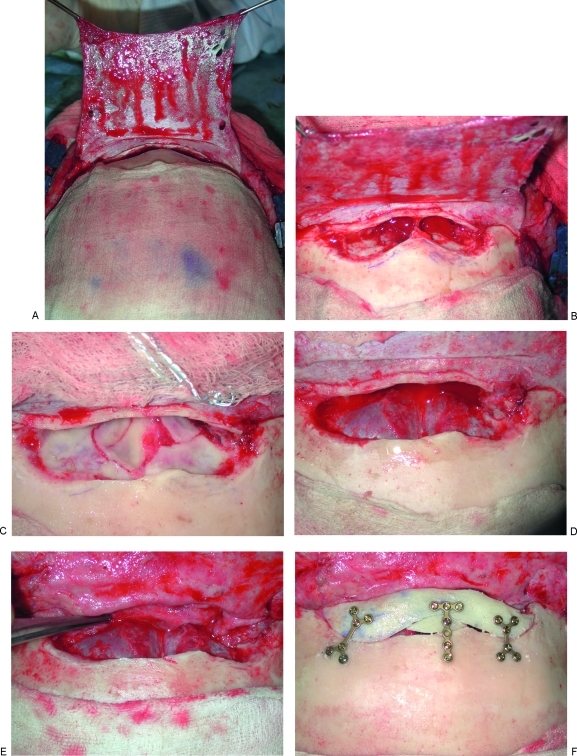

Figure 6.

Anterior and posterior table fracture with comminution and displacement of posterior table with CSF leak. (A) Elevation of pericranial flap, (B) comminution of posterior table with CSF leak, (C) posterior table fracture with dural tear, (D) cranialization with repair of dura, (E) placement of pericranial flap to separate anterior skull base from nasal cavity, (F) reconstruction of anterior table.

These severe and life-threatening conditions are seen more frequently with multiple fractures than with isolated fractures.25 Disease pathogens associated with meningitis include Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Pneumococcus, group C beta-hemolytic streptococcus, anaerobes, and gram-negative bacilli.26 Fungal infections are rare but certainly are possible in immunocompromised patients (zygomycosis).27,28 Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended with all frontal sinus fracture patients. It should be noted that in the pediatric patient population, the younger the patient the more devastating the consequences should meningitis occur.29,30

Additional complications include meningoencephalocele, acute and chronic osteomyelitis, subperiosteal abscess, Pott's puffy tumor, and chronic sinusitis.

INTRACRANIAL COMPLICATIONS

The incidence of intracranial complications is fortunately lower than that of skull-base problems. However, the severity of intracranial pathology seems to be greater and more devastating. These complications include intraparenchymal hemorrhage, brain abscess, pneumocephalus (Fig. 7), tension pneumocephalus, expanding pneumocephalus, intracerebral pneumatocele, meningitis, encephalitis, cerebral contusion, increased intracranial pressure (ICP), and chronic headache.31,32,33

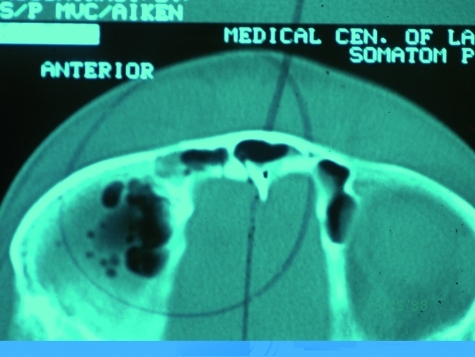

Figure 7.

Computed tomography scan of isolated posterior table fracture with pneumocephalus.

The most common of the intracranial injuries is chronic pain.31,34 This can range from a postconcussion syndrome to sinus headache. The pain is often out of proportion to the bony injuries and appears to be worse in multiple fractures than in simple fractures. There is no specific fracture pattern, complication, or somatic indicator that can predict who will and will not suffer a chronic pain syndrome.35 Pain may also be an indicator of a long-term complication such as mucopyocele, mucocele, or osteomyelitis. Chronic headache can represent anything from increased ICP to CSF leak to mucosal inflammation.36 Routine surveillance should include imaging, neurologic examination, ophthalmologic examination, and endoscopy.

An additional complication that can be seen with intracranial injury is blood loss. This is more often associated with scalp injury and panfacial fractures but can be seen with subdural, epidural, or intraparenchymal hemorrhage.25,33,37

OPHTHALMOLOGIC

Most ophthalmologic complications are related to orbital roof involvement within the frontal sinus fracture.38,39,40 The most devastating complication is blindness. This can be related to fracture extension into the lesser wing of the sphenoid but has been reported as orbital apex syndrome secondary to subdural hematoma of the optic nerve sheath.41,42 Orbital complications can be concomitant injuries, injuries related to surgical access, posttraumatic volume discrepancies, muscle entrapment, hematoma, or infectious. Reported complications include enophthalmos, exophthalmos, diplopia, macular hole, commotion retinae, retinal detachment, lens displacement, orbital mucopyocele, traumatic encephalocele, proptosis (+/− pulsatile), blurred vision, decreased visual acuity, blindness, orbital abscess, cellulitis, and ophthalmoplegia.40,43,44

Most of these complications are seen early in the disease process. Mucocele, encephalocele, volume loss, and cicatrix related problems are usually late complications. Once again, the need for lifelong surveillance and routine imaging is demonstrated by some of these late, debilitating complications.

MAXILLOFACIAL

Craniomaxillofacial injuries can be concomitant or related to surgical access and/or method of repair. These include chronic sinusitis, frontal sinus cutaneous fistula (Fig. 8), subperiosteal abscess, contour deformity (Fig. 9), osteomyelitis, decreased forehead sensation, paresthesias, dysesthesias, malunion, nonunion, hardware extrusion, and foreign body reaction. The most common related injuries are orbit, naso-orbital-ethmoid, nasal fracture, and midface fracture. The greater the number of concomitant injuries, the higher the risk for complication.2,45

Figure 8.

(A) Full-thickness injury through anterior and posterior tables of frontal sinus with loss of skin–soft tissue envelope and devitalized dura in the middle of the wound. (B) Outline for thoracodorsal artery perforator flap (T-DAP) for wound coverage. (C) Excellent pedicle length of T-DAP to reach neck if temporal vessels are not adequate. (D) Inset of T-DAP with closure of defect (vascularized fat used to obliterate remaining sinus). (E) Final result at 1-year postoperative visit.

Figure 9.

Frontal bone chronic contour irregularity after frontal impact trauma.

Injuries related to the skin–soft tissue envelope include scarring, dehiscence, flap loss, alopecia, scalp necrosis, facial nerve injury, decreased forehead sensation, and chronic pain. Most of these complications are related to the coronal incision and flap dissection. Some of these can be caused by blunt force trauma or penetrating injuries. Most of these complications occur early on and are usually mild.

CONCLUSION

Frontal sinus fractures represent only 5 to 12% of all maxillofacial fractures but due to the anatomic location of the sinus can have devastating sequelae. These can be skull base, intracranial, ophthalmologic or maxillofacial. They can involve brain, eye, bone, dura, muscle, or the skin–soft tissue envelope. These complications can be insidious and involve multiple organ systems.

We must recognize that frontal sinus fractures regardless of age, gender, fracture pattern, or method of repair are going to develop complications. With this knowledge, early detection and constant vigilance is our best defense. This means lifelong follow-up to include routine imaging, endoscopy, neurologic examination, and ophthalmologic evaluation.

Management of complications of frontal sinus fractures is often multidisciplinary. Involvement of plastic surgery, neurologic surgery, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, oral surgery, infectious disease, and critical care is often necessary for optimal outcomes.

Complications related to previous reconstruction of the frontal sinus can be extremely difficult. Principles to guide revision surgery include separation of the anterior cranial base from the nasal cavity preferably with vascularized tissue, thorough and complete mucosal removal, and use of autologous material for obliteration if necessary. If obliteration is required in an infected field, then cancellous bone is the material of choice (Fig. 10A,B).

Posterior table fractures with severe comminution, CSF leak, or nasofrontal ostia involvement should be treated with cranialization. If the posterior table is intact and the nasofrontal ostia are damaged, obliteration is the best treatment. If the anterior table is displaced and the nasofrontal ostia are intact, then reconstruction is the best option.

Figure 10.

(A) Obliteration of frontal sinus with pericranial flap and cancellous bone. (B) Reconstruction of anterior table with split-calvarial bone graft.

References

- Manolidis S, Hollier L H., Jr Management of frontal sinus fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(Suppl 2):32s–48s. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000260732.58496.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzinger S E, Guerra A B, Garcia R E. Frontal sinus fractures: management guidelines. Facial Plast Surg. 2005;21:199–206. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-922860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C, Mehendale N, Barrett D, Bui C J, Metzinger S E. 30-year retrospective review of frontal sinus fractures: the Charity Hospital experience. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma. 2000;6:7–15. discussion 16–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong E B, Pahlavan N, Saito D. Frontal sinus fractures: a 28-year retrospective review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:774–779. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolino P, Vetrano S, Mundula P, Di Lella G, Tedaldi M, Poladas G. Frontal bone fractures: new technique of closed reduction. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:695–698. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e318052ff45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley R B., Jr Fractures of the frontal sinus. Clin Plast Surg. 1989;16:115–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley R B., Jr Management of frontal sinus fractures. Facial Plast Surg. 1988;5:231–235. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1064757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley R B., Jr Management of severe frontobasilar skull fractures. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1991;24:139–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolidis S. Frontal sinus injuries: associated injuries and surgical management of 93 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:882–898. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce E A. Frontal sinus fractures: guidelines to management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:500–510. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198710000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller E M, Jacobs J B, Holliday R A. Evaluation of the frontonasal duct in frontal sinus fractures. Head Neck. 1989;11:46–50. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880110109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick B, Draf W, Kahle G, Weber R, Wallenfang T. Occult malformations of the skull base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:77–80. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900010087013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disa J J, Robertson B C, Metzinger S E, Manson P N. Transverse glabellar flap for obliteration/isolation of the nasofrontal duct from the anterior cranial base. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;36:453–457. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaller S R, Donald P. The use of pericranial flaps in frontal sinus fractures. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;32:284–287. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199403000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguet J, Bourdiniere J, Subileau C, Le Clech G. [Otorhinolaryngology and ethmoido-frontal injuries] J Fr Otorhinolaryngol Audiophonol Chir Maxillofac. 1977;26:95–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Clech G, Bourdinière J, Rivron A, Demoulin P Y, Inigues J P, Marechal V. [Post-traumatic infections of the frontal sinus] Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 1990;111:103–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotch D W. Frontal sinus fractures: anterior skull base. Facial Plast Surg. 2000;16:127–134. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-12574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis A, Donald P J. Frontal sinus fractures: a review of 72 cases. Laryngoscope. 1988;98(6 Pt 1):593–598. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198806000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald P J. The tenacity of the frontal sinus mucosa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1979;87:557–566. doi: 10.1177/019459987908700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain J, Chabannes J, Péri G, Jourde J. [Frontobasal injuries and CSF fistulas: attempt at an anatomoclinical classification. Therapeutic incidence] Neurochirurgie. 1975;21:493–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrich R J, Hollier L H. Management of frontal sinus fractures: changing concepts. Clin Plast Surg. 1992;19:219–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald P J, Bernstein L. Compound frontal sinus injuries with intracranial penetration. Laryngoscope. 1978;88(2 Pt 1):225–232. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197802000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D H. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:46–48. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200402000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D H. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:19–22. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piek J. Surgical treatment of complex traumatic frontobasal lesions: personal experience in 74 patients. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:e2. doi: 10.3171/foc.2000.9.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D H. The microbiology of paranasal sinus infections: diagnosis and management. CRC Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1978;9:105–121. doi: 10.3109/10408367809150917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglia A J, Goodwin W J, Arnold J E, Ganz E. Intracranial abscesses secondary to nasal, sinus, and orbital infections in adults and children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:1424–1429. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1989.01860360026011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove R N, Wesley R E, Klippenstein K A, Fleming J C, Haik B G. Indications for orbital exenteration in mucormycosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:286–291. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000225418.50441.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whatley W S, Allison D W, Chandra R K, Thompson J W, Boop F A. Frontal sinus fractures in children. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1741–1745. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000172199.50482.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D L, Hoffman H T, Hoyt D B. Frontal sinus fractures in the pediatric population. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:1215–1219. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199211000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day T A, Meehan R, Stucker F J, Nanda A. Management of frontal sinus fractures with posterior table involvement: a retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma. 1998;4:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbino G, Roccia F, Benech A, Caldarelli C. Analysis of 158 frontal sinus fractures: current surgical management and complications. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000;28:133–139. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranković D, Glavina K. Classification of frontal fossa fractures associated with cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, pneumocephalus or meningitis: indications and time for surgical treatment. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 1993;36:44–50. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khatib K, Danino A, Malka G. The frontal sinus: a culprit or a victim? A review of 40 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:314–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewine J D, Davis J T, Bigler E D, et al. Objective documentation of traumatic brain injury subsequent to mild head trauma: multimodal brain imaging with MEG, SPECT, and MRI. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22:141–155. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000271115.29954.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokisato K, Inatomi Y, Yonehara T, Fujioka S, Uchino M. [A case with bacterial meningitis caused by cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea 22 years after head trauma] Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2001;41:435–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aletsee C, Konopik V, Dazert S, Dieler R. [Surgery of anterior skull base fractures] Laryngorhinootologie. 2003;82:626–631. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martello J Y, Vasconez H C. Supraorbital roof fractures: a formidable entity with which to contend. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug R H, Sickels J E Van, Jenkins W S. Demographics and treatment options for orbital roof fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:238–246. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.120975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt G R, Holt J E. Incidence of eye injuries in facial fractures: an analysis of 727 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1983;91:276–279. doi: 10.1177/019459988309100313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi S J, Raji M R, Sprinkle P M, Weinstein G W, Minardi L M, Swanson T J. Computerized tomographic scan findings in facial fractures associated with blindness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68:479–490. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ey W. [Orbital involvement in frontobasal injuries] Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg) 1981;60:162–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K T, Chen C T, Mardini S, Tsay P K, Chen Y R. Frontal sinus fractures: a treatment algorithm and assessment of outcomes based on 78 clinical cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:457–468. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000227738.42077.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merville L. [Fronto-orbito-nasal dislocations: initial total reconstruction. Tactics, Advantages, Conditions] Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1977;78:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveh J, Laedrach K, Vuillemin T, Zingg M. Management of combined frontonaso-orbital/skull base fractures and telecanthus in 355 cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:605–614. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880060053014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]