Abstract

Reconstructive algorithms for composite craniofacial defects have focused on soft tissue flaps with or without bone grafts. However, volumetric loss over time limits long-term preservation of facial contour. Application of craniofacial skeletal buttress principles to high-energy trauma or oncologic defects with composite vascularized bone flaps restores the soft tissue as well as the buttresses and ultimately preserves facial contour. We conducted a retrospective review of 34 patients with craniofacial defects treated by a single surgeon with composite bone flaps at R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center and Johns Hopkins Hospital from 2001 to 2007. Data collected included age, sex, mechanism of injury, type of defect, type of reconstructive procedures, and outcome. Thirty-four patients with composite tissue loss, primarily males (n = 24) with an average age of 37.4 years, underwent reconstruction with vascularized bone flaps (28 fibula flaps and 6 iliac crest flaps). There were 4 cranial defects, 8 periorbital defects, 18 maxillary defects, and 4 maxillary and periorbital defects. Flap survival rate was 94.1% with an average follow-up time of 20.5 months. Restoration of facial height, width, and projection is achieved through replacement of skeletal buttresses and is essential for facial harmony. Since 2001, our unit has undergone a paradigm shift with regard to treatment of composite oncologic and traumatic defects, advocating vascularized bone flaps to achieve predictable long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Composite defect, skeletal buttress, microsurgery, facial reconstruction

Significant advances have occurred in craniofacial surgery during the last century, resulting in improved functional and aesthetic outcomes. First, novel surgical approaches to the craniofacial skeleton afford safe and predictable access to remote areas. Second, the structural pillars of the face responsible for maintaining height, width, and projection were defined and first applied to facial trauma reconstruction. Third, the development and refinement of computerized tomography allowed anatomic diagnosis and accurate repair. Fourth, earlier restoration of hard and soft tissue craniofacial defects prevents spherical scar contracture. Last, introduction of microsurgical techniques facilitates predictable coverage of complex craniofacial defects.

Although soft tissue flaps initially provide adequate volume, if not supported by a boney framework, soft tissue ptosis and loss of facial projection occurs over time. Conventional bone grafts have been combined with soft tissue flaps, but nonvascularized bone undergoes unpredictable resorption1 and does not provide an adequate foundation for an osseointegrated prosthesis. Although vascularized bone flaps are used frequently to restore composite mandibular defects,2 there has been some reservation with application of this principle to the periorbital and midfacial regions.

Principles of buttress restoration were applied to reconstruct composite facial defects with vascularized bone flaps. Rather than recreating the missing curvilinear facial skeleton, we recreate strategic bony girders necessary to preserve function and maintain facial proportions with vascularized bone flaps.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Thirty-four patients underwent microvascular craniofacial reconstruction with either a fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap3 or an iliac crest flap4 for traumatic or oncologic defects at the R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center and Johns Hopkins Hospital from 2001 to 2007. The indication for a vascularized bone flap was either soft tissue or segmental bone loss, prior failed attempts at reconstruction with conventional methods, and at least one key missing buttress. Charts were reviewed and data collected including age, sex, mechanism of injury, type of defect, type of reconstructive procedures, and outcome.

RESULTS

The majority of patients were male (n = 24) with an average age of 37.4 years (range 21 to 65 years). The majority of defects were traumatic (n = 27). A combination of buttresses was reconstructed including the supraorbital bar (n = 4), infraorbital rim and zygomaticomaxillary buttress (n = 6), infraorbital rim and nasomaxillary buttress (n = 1), infraorbital rim and orbital floor (n = 1), infraorbital rim and maxillary arch (n = 4), zygomaticomaxillary buttress (n = 1), and maxillary arch (n = 17). All patients with defects of the cranial (n = 4) and periorbital (n = 7) regions were reconstructed with fibula flaps (n = 11). Half of the patients with maxillary defects were reconstructed with iliac flaps (n = 6) and the remaining with fibula flaps (n = 11).

Two of the 34 flaps failed; both were fibulas. One was for periorbital reconstruction and the other was for maxillary reconstruction. One failure was due to a hematoma compressing the pedicle, and the other was due to hemodynamic instability requiring vasopressors. There were no patient mortalities.

Six of the 27 patients with traumatic defects underwent immediate reconstruction (within 13 days of the initial injury). The 21 patients who underwent delayed reconstruction had prior attempts at reconstruction using local, distant, or free soft tissue flaps combined with nonvascularized bone grafts. Collapse of the bony architecture and disfiguring soft tissue contracture prompted secondary reconstruction. Four of the six patients with defects from cancer extirpation were reconstructed immediately, and the remaining patients were referred for secondary reconstruction following hardware exposure and soft tissue breakdown. One syndromic patient had undergone an extracranial Le Fort III osteotomy and cleft palate repair as a child. The palatal cleft recurred and the maxilla was severely hypoplastic; therefore, the patient underwent reconstruction with a fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap.

Seventeen of the 34 patients underwent secondary procedures including osseous contouring (n = 14), flap debulking (n = 13), volume augmentation with an anterolateral thigh flap (n = 3), distraction osteogenesis of the free fibula flap (n = 2), cranioplasty (n = 1), and maxillary bone augmentation (n = 2). These procedures were done to improve the overall aesthetic and functional outcome. In particular, skin color mismatch (the skin paddle of the deep circumflex iliac artery [DCIA] or fibula flap) can be improved by serial excision and local tissue advancement.

To date, five patients had successful dental rehabilitation with osseointegrated implants and seven others have begun the process. The average follow-up time was 20.5 months (range 6 to 64 months).

DISCUSSION

Sicher and De Brul appreciated the architectural support of the orbital, nasal, and oral functional units.5 Re-establishment of these buttresses is essential for the maintenance of midface height, width, and projection. Manson et al6 and Gruss and Mackinnon7 restored facial proportions through vertical and horizontal buttress reconstruction when treating craniofacial fractures. The frontal bandeau defines the contour of the upper third of the face. The inferior orbital rim and malar prominence define the width and projection of the midface, which is the site of fixation for floor defects as well as osseointegrated orbital prosthesis.8 The maxillary alveolus and piriform aperture provide the platform for nasal reconstruction and osseointegrated dental implants.

Facial buttress replacement with vascularized bone preserves skeletal projection, minimizes soft tissue descent, and provides the foundation for a variety of osseointegrated prostheses. Soft tissue alone is inadequate to maintain projection and support the forces of mastication over time. Conventional bone grafts have proved useful in craniofacial fracture treatment provided the defects are small and surrounding tissue is well vascularized. However, nonvascularized bone grafts undergo unpredictable resorption and occasionally require secondary onlay grafting to correct volumetric deficiencies.7 This approach is impractical when treating high-energy injuries or large oncologic resections in which the defects are composite, the surrounding tissue is poorly vascularized, or radiation is anticipated. Our experience confirms that denervated free muscle flaps atrophy and result in soft tissue breakdown and exposure of hardware or bone (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A 53-year-old man who sustained a gun shot wound to the face. He underwent reconstruction with a free rectus abdominis flap and nonvascularized rib graft. At 2 years, the muscle has atrophied and the bone resorbed, resulting in poor contour and projection.

A variety of vascularized bone flaps have been described for midfacial skeletal reconstruction including calvarium, rib, scapula, radius, ilium, and fibula.9,10 Coleman11 and Cordeiro and Santamaria12 obliterated composite midface and orbital defects with soft tissue myocutaneous flaps and add conventional bone grafts to restore globe position. Yamamoto et al reconstructed maxillectomy defects by replacing the three principal midfacial buttresses using a myocutaneous free flap combined with bone autografts (scapula or rib).13 None of the approaches described to date simultaneously address the missing skeletal buttresses and provide a functional foundation for an osseointegrated prosthesis.

Coleman and Sultan14 and Vinzenz et al15 described single stage reconstruction of the maxillary alveolar arch, orbital rim, and orbital floor with the scapular flap.16 Although both buttresses were reconstructed with vascularized bone, the scapular flap has several disadvantages including the need to reposition the patient, precluding a two-team approach, limiting bone stock, and shortening pedicle length. The iliac crest and fibula free flaps are better options for vascularized reconstruction of the upper face. The iliac crest free flap provides ideal bone stock for osseointegrated implants, and the associated internal oblique muscle can be used for intraoral resurfacing. Although the iliac crest free flap may be used for bilateral maxillary defects, it is best suited for a unidimensional skeletal defect that requires minimal manipulation given its short pedicle and bulky skin island.17 The fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap, on the other hand, is ideal for simultaneous maxillary and periorbital reconstruction. It provides ample bone stock for both dental and orbital osseointegrated prostheses18 and long pedicle length, which is particularly useful when adjacent donor vessels are limited. Furthermore, the reliable skin paddle may be used to resurface external and oral lining defects, as well as obliterate the paranasal sinuses and exenteration defects.19,20

The authors advocate the fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap for reconstructing the frontal bar, nasal, or periorbital regions. Multiple osteotomies can be made predictably to manipulate the bone and accommodate a variety of missing buttresses. The specific number of osteotomies and configuration of the fibula are tailored based on the missing subunits—frontal bar, orbital rims, malar prominence, and/or maxillary alveolus (Figs. 2, 3, and 4).

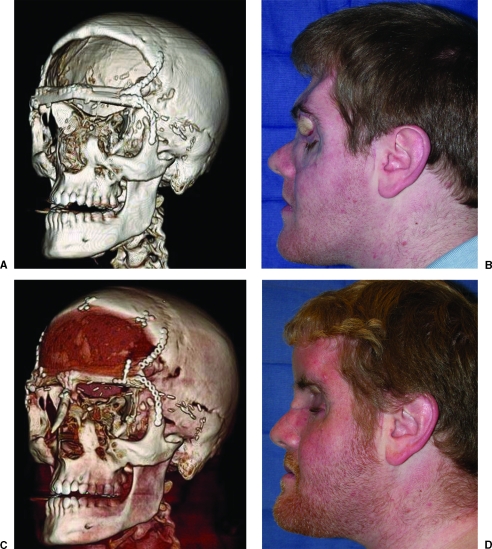

Figure 2.

A 23-year-old man involved in a high-speed motor vehicle collision who sustained a comminuted frontal bone fracture. The sinonasal tract was not completely obliterated, resulting in infection of the bovine pericardium dural reconstruction. The nonvascularized frontal bone and the infected frontal lobe were debrided. The frontal bandeau was reconstructed with a free fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap. The soft tissue was used to obliterate the sinus and the bone was used to reconstruct the buttress. (A) Postoperative computed tomography (CT). (B) Postoperative clinical photograph. (C) Postoperative CT following methyl methacrylate cranioplasty and nasal dorsal bone graft stabilization to the fibula. (D) Postoperative clinical photograph.

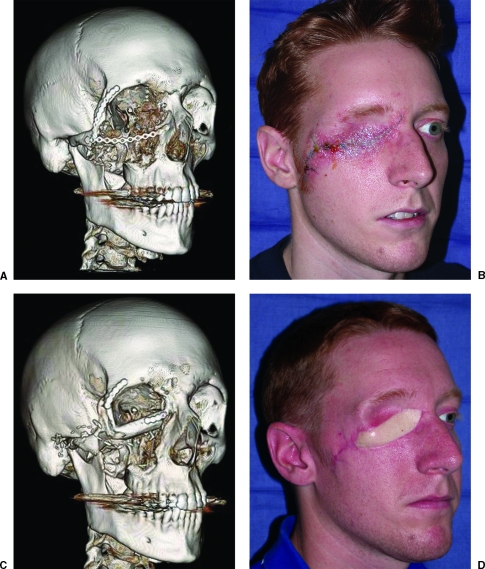

Figure 3.

A 23-year-old soldier who sustained a high-energy gunshot wound to the periorbital region. The orbital rim was initially reconstructed with a miniplate; however, the overlying soft tissue broke down, resulting in plate exposure. A free fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap was used to reconstruct the orbital rims and provide a foundation for an osseointegrated prosthesis. (A) Preoperative computed tomography (CT). (B) Preoperative clinical photograph. (C) Postoperative CT. (D) Postoperative clinical photograph.

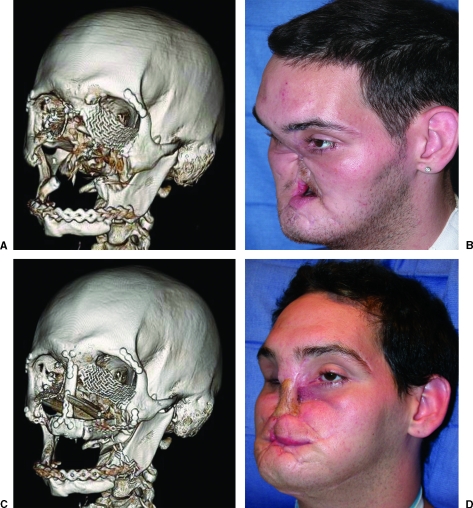

Figure 4.

A 25-year-old man who sustained a submental self-inflicted gun shot wound. A free fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap was used to reconstruct the entire maxillary dentoalveolus. The fibula skin flap was used to obliterate the palatal fistula and provide nasal lining. (A) Preoperative computed tomography (CT). (B) Preoperative clinical photograph. (C) Postoperative CT. (D) Postoperative clinical photograph.

The goals of periorbital reconstruction include restoration of malar projection, placement of a platform for an orbital implant, and correction of enophthalmos and vertical dystopia (Figs. 3 and 5). The goals of midface reconstruction include restoration of maxillary projection, separation of the respiratory and alimentary tracts, and creation of a foundation for nasal and dental reconstruction (Figs. 4 and 5). The maxilla is the platform for the nose and should be reconstructed before embarking on nasal reconstruction (Fig. 4). We have found that immediate reconstruction in trauma cases, within the first 10 to 20 days, optimizes aesthetic outcomes. Early replacement of skeletal support keeps the soft tissue envelope expanded, maintains volume, and prevents spherical contracture.

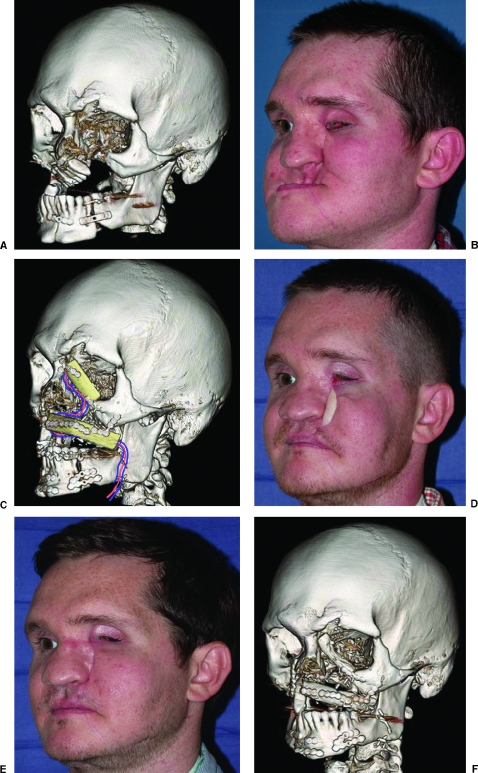

Figure 5.

A 30-year-old man who sustained a self-inflicted submental gunshot wound. When he presented to us, he had undergone poor stabilization of the maxilla and mandible. Corrective maxillary and mandibular osteotomies were performed, and a free fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap was used to reconstruct the orbital rim and maxillary dental alveolus. Both will provide a foundation for osseointegrated ocular and dental prostheses. Secondary revisions to achieve optimal cosmetic outcomes are almost always required. (A) Preoperative computed tomography (CT). (B) Preoperative clinical photograph. (C) Postoperative CT with diagram of fibula flap and vascular pedicle. (D) Postoperative clinical photograph following osteotomies and fibula flap. (E) Postoperative clinical photograph following secondary revisions including periorbital bone recontouring, excision of the fibula skin paddle, and cervicofacial flap advancement. (F) Postoperative CT.

Routinely, multiple procedures are required to achieve optimal results. The initial stage involves vascularized recruitment of volume and skeletal support, and secondary procedures are required to optimize contour, shape, and skin-color match (Figs. 2C, 2D, 5E, and 5F). In our experience soft tissue requirements are often underestimated. To address this, we deliver excess soft tissue initially and anticipate small secondary shaping and contouring procedures.

Our approach is based on functional skeletal replacement rather than patterns of defects and advocates vascularized composite tissue restoration with a well-designed fibula or iliac crest flap. Our unit has undergone a major paradigm shift with regards to treatment of composite oncologic or traumatic defects and now advocates vascularized bone flaps to achieve stable, long-term functional and cosmetic outcomes.

SUMMARY

In the last century the importance of re-establishing the skeletal buttresses was appreciated in rigid fixation of acute traumatic craniofacial injuries. This experience represents a true partnership between craniofacial surgery and microsurgery and is uniquely applicable for composite facial defects from any etiology.

References

- Hidalgo D A, Rekow A. A review of 60 consecutive fibula free flap mandible reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:585–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Blake F, Heiland M, Schmelzle R, Pohlenz P. Long-term evaluation after mandibular reconstruction with fibular grafts versus microsurgical fibular flaps. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:281. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F C, Chen H C, Chuang D C, Noordhoff M S. Fibular osteoseptocutaneous flap: anatomic study and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:191–200. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198608000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J S. Deep circumflex iliac artery free flap with internal oblique muscle as a new method of immediate reconstruction of maxillectomy defect. Head Neck. 1996;18:412–421. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199609/10)18:5<412::AID-HED4>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicher H, De Brul E L. Oral Anatomy. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1970. p. 78.

- Manson P N, Hoopes J E, Su C T. Structural pillars of the facial skeleton: an approach to the management of Le Fort fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66:54–62. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss J S, Mackinnon S E. Complex maxillary fractures: role of buttress reconstruction and immediate bone grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triana R J, Uglesic V, Virag M, et al. Microvascular free flap reconstructive options in patients with partial or total maxillectomy defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2000;2:91–101. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.2.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Minakawa H, Kawashima K, Furukawa H, Sugihara T, Nohira K. Role of buttress reconstruction in zygomaticomaxillary skeletal defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:943–950. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199804040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futran N D, Mendez E. Developments in reconstruction of midface and maxilla. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:249–258. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70616-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J J., 3rd Osseous reconstruction of the midface and orbits. Clin Plast Surg. 1994;21:113–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro P G, Santamaria E. A classification system and algorithm for reconstruction of maxillectomy and midfacial defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2331–2346. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Kawashima K, Sugihara T, et al. Surgical management of maxillectomy defects based on the concept of buttress reconstruction. Head Neck. 2004;26:247–256. doi: 10.1002/hed.10366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J J, 3rd, Sultan M R. The bipedicled osteocutaneous scapula flap: a new subscapular system free flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:682–692. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinzenz K G, Holle J, Wuringer E, Kulenkampff K J. The prefabricated combined scapula flap for bony and soft-tissue reconstruction in maxillofacial defects: a new method. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:542–552. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199609000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schusterman M A, Reece G P, Miller M J. Osseous free flaps for orbit and midface reconstruction. Am J Surg. 1993;166:341–345. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J S. Deep circumflex iliac artery free flap with internal oblique muscle as a new method of immediate reconstruction of maxillectomy defect. Head Neck. 1996;18:412–421. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199609/10)18:5<412::AID-HED4>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodel J L, Jr, Funk G F, Capper D T, et al. Osseointegrated implants: a comparative study of bone thickness in four vascularized bone flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:449–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim K K, Wei F C. Fibula osteoseptocutaneous free flap in maxillary reconstruction. Microsurgery. 1994;15:353–357. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920150513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futran N D, Wadsworth J T, Villaret D, et al. Midface reconstruction with the fibula free flap. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:161–166. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]