Abstract

Background

Despite evidence of the importance of cervical cancer screening, screening rates in the United States remain below national prevention goals. Women in the Appalachia Ohio region have higher cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates along with lower cancer screening rates. This study explored Appalachian Ohio women’s expectations about Pap test cost and perceptions of cost as a barrier to screening.

Methods

Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 571 women who were part of a multilevel observational community-based research program in Appalachia Ohio. Eligible women were identified through 14 participating health clinics and asked questions about Pap test cost and perceptions of cost as a barrier to screening. Estimates of medical costs were compared to actual costs reported by clinics.

Results

When asked about how much a Pap test would cost, 80% of the women reported they did not know. Among women who reportedly believed they knew the cost, 40% overestimated test cost. Women who noted cost as a barrier were twice as likely to not receive a test within screening guidelines as those who did not perceive a cost barrier. Further, uninsured women were more than 8.5 times as likely to note cost as a barrier than women with private insurance.

Conclusions

While underserved women in need of cancer screening commonly report cost as a barrier, these findings suggest that women may have a very limited and often inaccurate understanding about Pap test cost. Providing women with this information may help reduce the impact of this barrier to screening.

Keywords: Pap test, disparities, perception of cost, access, cost barriers, underserved populations, Appalachia, cancer screening

BACKGROUND

Pap test rates remain below the national prevention goal that 90% of women 18 years and older should have received a Pap test within the past 3 years1 despite efforts to improve screening rates. In general, screening has proved a particularly important tool to reduce the impact of certain cancers, especially for slow-growing, preventable cancers such as cervical cancer.2,3 Yet, 2005 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data showed that one in five women (20.4%) did not receive a Pap test in the past three years.4 Given estimates that 11,270 new cases of invasive cervical cancer and 4,070 deaths are predicted to occur in 2009,5 the importance of improving screening rates in order to improve women’s survival rates through early detection cannot be underestimated.

In the Appalachia Ohio region of the U.S., an area characterized by lower income, higher unemployment rates, and lower levels of education,6–8 recent research has shown both greater cancer incidence and mortality rates, along with lower prevalence of cancer screening behaviors.9 Cervical cancer incidence rates reported in 2006 were 37% higher among women in Appalachia Ohio compared to women from Non-Appalachia Ohio, and mortality rates from cervical cancer were 44% higher for women from Appalachia Ohio compared to their Non-Appalachia Ohio counterparts.9 Rates of receipt of a Pap smear in the past 3 years showed similar differences, with women from Appalachia Ohio having a rate 9% lower than women from Non-Appalachia Ohio.9

Numerous barriers to women’s receipt of cervical cancer screening have been identified including sociodemographic factors of age, income, and education,7,10–13 behavioral factors such as understanding of screening benefits, fear of cancer, and embarrassment,10,13–15 and provider factors including physician perceptions15 and practice characteristics.13,16 For women residing in Appalachia Ohio, recent research has suggested that the factors of cost, insurance coverage, and perceptions about the test itself (e.g., embarrassment, privacy issues) may be particularly salient barriers to cervical cancer screening.17 In addition, prior research has explored the issues of cost and insurance coverage in relation to other cancer screening practices including mammograms e.g., 18,19 and colorectal cancer screening tests.e.g., 20 However, no studies have investigated the importance of these barriers relative to cervical cancer screening practices in this underserved population. This research was designed to explore women’s expectations about Pap test cost and perceptions of cost as a barrier to cervical cancer screening among an underserved population of women residing in Appalachia Ohio.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

The data for this study are from interviews conducted from 2005 to 2006 as part of the CARE “Reducing Cervical Cancer in Appalachia” study, a multi-level observational community-based research program designed to understand why high rates of cervical cancer incidence and mortality are observed in Appalachia Ohio. As part of this study, 22 health clinics were identified in Appalachia Ohio, each of which performed more than 200 Pap smear tests per month. Fourteen of those clinics agreed to participate in the study; their patient rolls were randomly sampled to identify women who might be eligible for the study.

The survey instrument was designed to gather information about the women’s demographics, sources of medical care, knowledge and beliefs about cervical cancer and Pap smear screening, cost, and health and sexual history. The cross-sectional survey was ultimately completed, in face-to-face interviews, by 571 eligible women whose responses are used in these analyses. Detailed study design and procedures have been summarized previously. 21 Informed consent procedures and study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of The Ohio State University, University of Michigan, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe study population demographics and cervical cancer screening history. Additional analyses were conducted to investigate perceptions of Pap test cost as a barrier to care access. We analyzed women’s perceptions of Pap test costs and compared perceptions of Pap test medical costs with the actual medical cost of cervical cancer screening for the study population, and with women’s actual Pap test utilization. We also compared Pap test cost perceptions with study participants’ perceived and actual risk of cervical cancer. All comparisons were tested using the Fisher exact test. A mixed effects logistic regression model was used to explore the factors associated with a woman’s propensity to say that the cost of a Pap smear was an obstacle for her. Explanatory variables in the model included age, insurance, income, education, marital status, and level of worry about cervical cancer. All of the variables were either dichotomous or categorical. Random effect intercepts were computed to account for correlation in the data at the level of individual health clinics. Due to the lack of readily available methods for mixed models with dichotomous outcomes, the model fit and discrimination were calculated using the marginal model with clinic as a fixed effect using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and the area under the ROC curve.22

All analyses were carried out with SAS (version 9.1 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), STATA software (version 10.0, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX), and Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

Key Variables

Interviewers asked each woman about her health history and demographics, her insurance coverage, and her perception of Pap test costs. Several additional variables were constructed from the survey data. The paragraphs that follow describe how those variables were calculated.

Pap test cost perceptions

Respondents were asked three questions: First, “About how much does a Pap smear cost in your community?” Valid responses consisted of a dollar figure, or “I do not know.” Second, regardless of their response to the preceding question, each woman was next asked to select a cost category: “Would you expect it to cost: Not more than $10; $10–25; $26–50; $51–75; $76–100; $101–150; More than $150.” Valid responses included one of the categories above, or “I do not know.” Later in the interview, women were asked, “Does the cost of a Pap smear make it hard for you to get one?” Valid responses included “Yes,” “No,” or “I do not know.”

Accuracy of cost estimate

For this study, each woman was classified as to whether her perception of Pap test cost was accurate or not. Her response to the cost category question (the second question) was used to gauge whether her cost perception was in the “appropriate” range. The “appropriate” range was determined by polling participating clinics about the cost of a Pap smear. Clinics’ answers ranged from $28 to $90. The relatively wide range provides for a conservative estimate. However, to assess accuracy, we compared this range with the Medicare fee schedule for Ohio providers and found that provider reimbursement at the time of the study was $38.45 for Pap smear (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid). In our analyses we used the conservative range of costs, coding cost perception as “appropriate” if the estimate was between $26 to $100, “under” if < $26, or “over” if the response was > $100. Women who responded, “I do not know” formed a fourth category.

Health insurance status

Respondents were asked about current health insurance coverage. Possible responses included: a) private insurance, either through someone’s job or purchased by the respondent’s family; b) primarily Medicaid; c) primarily Medicare; or d) no insurance. Respondents could select more than one source of health insurance.

Risk of cervical cancer

Respondents were classified as high risk if they: had ever been diagnosed with HIV, gonorrhea, genital herpes, syphilis, or venereal warts, or if they were a current smoker, ever had a sexual partner with an STD, were younger than 18 the first time they had sex, or if their number of lifetime sexual partners was more than four. Otherwise, they were classified as at low risk for cervical cancer.

Perceived risk of cervical cancer

Participants were asked, “How would you rate your own risk of getting cervical cancer in the next five years, compared to other women you know? Would you say your risk is: much lower, somewhat lower, about the same, somewhat higher, or much higher?” The responses were collapsed into four categories: lower, about the same, higher, and “I do not know.”

Level of worry

Women were asked, “How much do you worry about getting cervical cancer?” Valid responses were “A lot,” “Some,” and “Not at all.”

Pap test within guidelines

If the respondent was at low risk for cervical cancer, then she was considered to be within Pap test guidelines if she had a Pap test any time in the three years preceding the interview. If she was at high risk for cervical cancer, then she was considered to be within guidelines if she had a Pap test in the year leading up to the interview. Otherwise, she was classified as not having had a Pap test within guidelines.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Population

The study population (n=571) reflects the population of Appalachia Ohio—a group that is predominantly white and includes many low-income residents. Table 1 presents demographic and Pap test history characteristics of this sample. Across study participants, nearly all (95%) were white, and over half (56%) reported an annual household income lower than 200% of the Federal poverty level; around one-third (34%) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Fifty-six percent of the respondents were privately insured while 18% reported Medicaid and 15% were uninsured. Less than 5% of this sample were covered by Medicare.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Pap Test History of Study Participants, by Group (n=571)

| Characteristic | Number of respondents (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 241 (42 %) |

| 35–49 | 190 (33 %) |

| 50+ | 140 (25 %) |

| Race | |

| White | 540 (95 %) |

| Black or African American | 17 (3 %) |

| Other | 14 (2 %) |

| Income < 200% of Federal Poverty Level | |

| No | 240 (44 %) |

| Yes | 303(56 %) |

| Income | |

| < $20,000 | 185 (34 %) |

| $20,001 – $35,000 | 119 (22 %) |

| $35,001 – $50,000 | 92 (17 %) |

| > $50,000 | 147 (27 %) |

| Insurance | |

| Private only | 315 (56 %) |

| Medicaid | 137 (24 %) |

| Medicare | 28 (5 %) |

| No insurance | 86 (15 %) |

| Education | |

| < High school | 46 (8 %) |

| High school graduate/GED | 206 (36 %) |

| Some college/college graduate | 319 (56 %) |

| Working status | |

| Full-time, part-time, or self employed | 378 (66 %) |

| Other (homemaker, student, retired, disabled, or unemployed) | 193 (34 %) |

| Marital status | |

| Not married | 222 (39 %) |

| Married or member of a couple | 349 (61 %) |

| Pap Test History | |

| Doctor encouraged a Pap test | |

| No | 377 (66 %) |

| Yes | 193 (34 %) |

| History of an abnormal Pap test | |

| No | 370 (65 %) |

| Yes | 197 (35 %) |

| Pap within guidelines | |

| No | 182 (32 %) |

| Yes | 380 (68 %) |

| At high risk for cervical cancer | |

| No | 117 (21 %) |

| Yes | 441 (79 %) |

| Worry about getting cervical cancer | |

| A lot | 38 (7 %) |

| Some | 185 (32 %) |

| Not at all | 347 (61 %) |

Among respondents, nearly one-quarter (24%) reported that they had been without health insurance coverage at some time during the last 12 months. In addition, one in five women (19%) noted that during the last 12 months there was a time that they needed health care but did not get it because they could not afford it.

The majority (66%) of participants reported that their doctor did not encourage a Pap test. Further, although 35% of participants reported an abnormal Pap test in the past, only 68% of respondents had received a Pap within guidelines.

Perceptions of Cost as a Barrier and Receipt of Pap Test within Guidelines

Nearly one in five women participants (18%) reported that the cost of a Pap smear made it hard for them to get the test. Among women who had not received a Pap test within the past three years and who gave a specific reason for not getting screened (n=34), one-third (29%) reported cost as the reason, and 18% stated that their insurance does not cover the test. Further, women who said that the cost of a Pap smear made it hard to get one were significantly more likely to not receive a Pap test within guidelines (OR=2.09; 95% CI =1.31–3.33; p=.002). Receipt of a Pap test once every three years for low-risk women and once per year for high-risk women was considered to be within screening guidelines.

Across participating women who had not received a Pap test within guidelines (n=183), only 22% had reportedly heard of any program to help pay for Pap smears. Only 14% had heard of the Breast and Cervical Cancer Control Program (BCCCP), the reduced cost program designed to help women afford screening tests for breast and cervical cancer. Of the total study sample (n=571), only 7 women (1.2%) reported having received a Pap test paid for with BCCCP funding.

Pap Test Cost Expectations

When asked, “About how much does a Pap smear cost in your community?” the great majority of study participants responded, “I do not know” (81%) (Table 2). The remaining 106 women provided numerical responses to the question (i.e., gave a dollar value). Expectations of Pap test cost for study participants are summarized in Table 2. Among these respondents, the highest dollar figure reported was $400, and the lowest was $0. As noted earlier, at the time these interviews were conducted, the actual cost of a Pap test in these communities ranged from $28 to $90. Thus, 42% of responding women overestimated the cost of a Pap test by at least $10, and nearly one in five overestimated the cost by at least $60.

TABLE 2.

Pap Test Cost Expectations

| How much respondents expected a Pap test to cost, with no guidance about cost categories (n=571) | |

| Response (n=571) | Number of respondents (%) |

| Gave dollar value response | 106 (19%) |

| Responded “I do not know” | 465 (81%) |

| Response Range (dollar value provided) (n=106) | Number of respondents (%) |

| $0–$99 | 61 (58%) |

| $100–$150 | 27 (25%) |

| Over $150 | 18 (17%) |

| How much respondents expected a Pap test to cost, by cost category provided (n=571) | |

| Cost Category | Number of respondents (%) |

| Not more than $10 | 2 (1%) |

| $10–$25 | 24 (4%) |

| $26–$50 | 59 (10%) |

| $51–$75 | 98 (17%) |

| $76–$100 | 119 (21%) |

| $101–$150 | 130 (23%) |

| More than $150 | 87 (15%) |

| Don’t know | 51 (9%) |

In response to the second question about cost, women provided estimates in different cost categories (Table 2). When presented with potential cost categories, more women were willing to estimate Pap test cost (i.e., only 9% of respondents reported “I don’t know”), but similar proportions overestimated the test cost (38% overestimated by at least $10; 15% overestimated by at least $60).

Accuracy of Pap Test Cost Perceptions

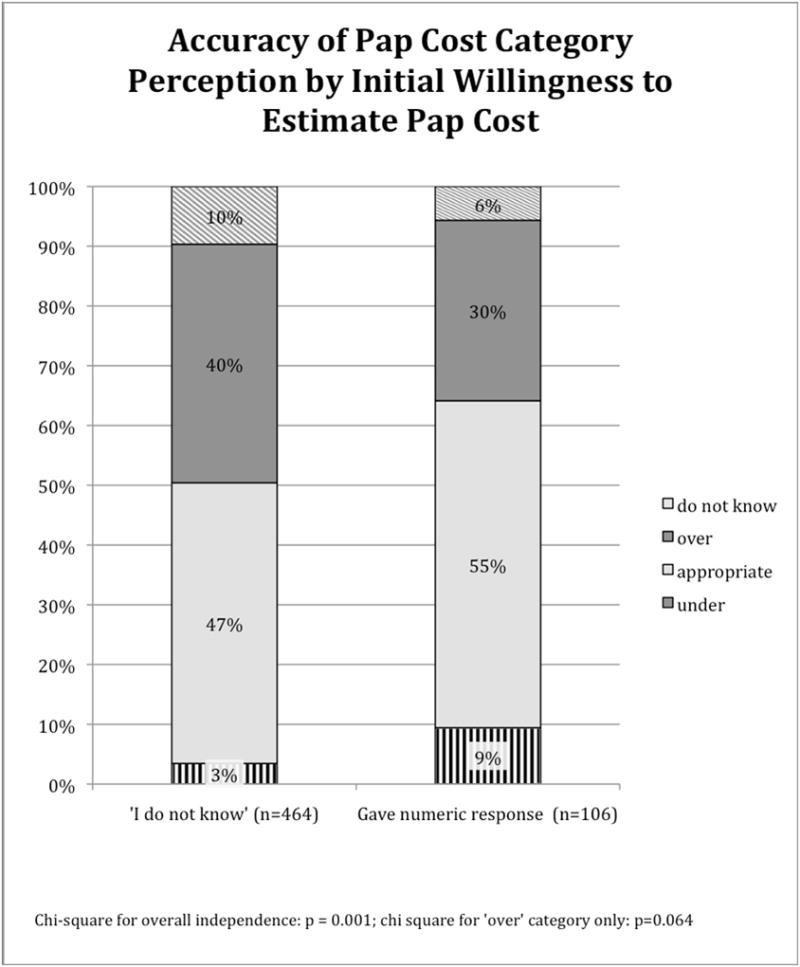

The accuracy of Pap test costs perception was compared between women who were initially willing to provide a numeric cost estimate in dollars (n=106) and women who were unable to estimate or answered that they did not know (n=464). The first question was used only to categorize whether the women were willing to provide an unaided cost estimate; the cost estimates that were compared between groups were the categorical responses to the second cost question. The accuracy of Pap test cost estimates were then categorized as “appropriate,” “under,” “over,” and “do not know” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Women in both groups were more likely to overestimate than underestimate the cost of a Pap test. Women who provided a numeric cost estimate initially were more likely to appropriately estimate the Pap test cost compared to those who initially did not know the cost of a Pap test. In addition, women who said, “I do not know” to the first question were more likely to overestimate the cost of a Pap test in the follow-up categorical question than women who gave a numeric response (40% vs. 30%; p=0.064). Women who said, “I do not know” were also less likely to underestimate the cost of a Pap test (3% vs. 9% respectively; p=0.016).

Perceptions of Cost as a Barrier to a Pap Test

Insurance status, income, and educational attainment were significantly related to stating that the cost of a Pap test makes it hard to get one, with insurance status having the strongest association. Table 3 lists the adjusted odds ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals for the main effects in the logistic regression model. The odds of a woman with no insurance saying that cost makes it difficult to get a Pap test were 8.66 times those of a woman with private insurance (95% CI = 4.20–17.82). A woman with Medicaid coverage, on the other hand, had odds of saying that cost was an obstacle that were 0.35 times those of a woman with private insurance (95% CI = 0.15–0.80).

TABLE 3.

Associations between independent variables and stating cost makes it difficult to obtain a Pap test (n=571)

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Insurance Coverage | ||

| Private only | 1.00 | -- |

| Medicaid | 0.35** | 0.15 – 0.80 |

| Medicare | 0.28 | 0.05 – 1.49 |

| No insurance | 8.66** | 4.20–17.82 |

| Age | ||

| ≥50 | 1.00 | -- |

| 35–49 | 1.14 | 0.54–2.39 |

| 18–34 | 0.85 | 0.39–1.88 |

| Income | ||

| ≥ 200% of poverty line | 1.00 | -- |

| < 200% of poverty line | 2.17* | 1.11–4.23 |

| Education | ||

| Some college or college graduate | 1.00 | -- |

| High school or GED | 1.79* | 1.01–3.19 |

| Less than high school | 2.49 | 0.95–6.54 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or member of a couple | 1.00 | -- |

| Not a member of a couple | 1.56 | 0.88–2.77 |

| Worry about cervical cancer | ||

| Not at all | 1.00 | -- |

| Some | 1.32 | 0.73–2.37 |

| A lot | 0.90 | 0.31–2.64 |

P ≤ 0.06

P ≤ 0.01

The odds of a woman whose income was below 200% of the federal poverty level saying that cost was a barrier were 2.17 times higher than those of a woman with income above 200% of the poverty level (95% CI = 1.11–4.23). Furthermore, women with less education had higher odds of saying that the cost of a Pap test makes it hard to get one. Women who completed high school had odds of responding that cost is an obstacle that are 1.79 times higher than women who had been to college (95% CI = 1.01–3.19). Women who failed to complete high school had odds of reporting cost as an obstacle that were 2.49 times those of college-educated women (95% CI = 0.95–6.54).

The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test indicates that the model fit the data reasonably well; the test fails to reject the null hypothesis of good fit, with p=0.7984. Furthermore, the model has good predictive power; the area under the ROC curve is 85%.

Risk Knowledge and Cost Factors

Overall, 441 women (79%) were found to be at high risk for cervical cancer based on their sexual and medical histories and smoking status. Women at high risk for cervical cancer were compared with those at low risk by comparing the proportion in each group who said that the cost of a Pap smear makes it hard for them to get one. Notably, women at high risk were more likely to say that the cost makes it difficult for them to get a Pap test than women at low risk (20% vs. 12%; p=0.058). Yet these women were not always aware of their high-risk status. Among women who were found to be at high risk of developing cervical cancer, 54% reported that they perceived their risk as being the same as that of other women they know, 22% reported their risk as being higher, and 20% reported their risk as being lower. In contrast, among women who were found to be at low risk of developing cervical cancer, 52% reported that they perceived their risk as being the same as that of other women they know, 6% reported their risk as being higher, and 38% reported their risk as being lower. Table 4 shows these comparative proportions based on risk.

TABLE 4.

Perceived Cervical Cancer Risk vs. Risk Calculated from Risk Factors (n=557)

| Perception of own risk compared to other women you know: | Risk status estimated from health and sexual history and smoking status* Number of respondents (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Low-Risk | High-Risk | |

| Do not know | 5(4%) | 20(5%) |

| Lower | 44(38%) | 88(20%) |

| About the same | 61(52%) | 237(54%) |

| Higher | 7(6%) | 95(22%) |

| Total | 117 | 440 |

Chi-square test for overall independence: p=0.0001.

DISCUSSION

Underserved women in need of an important cancer screening test commonly report cost as a barrier to screening as well as to receipt of needed medical care. However, our findings suggest that women in Appalachia Ohio have a very limited and often inaccurate understanding of the cost of cervical screening. Women in our study either reported no knowledge of Pap test cost or tended to overestimate the cost. Specifically, we found that four in five women reported no knowledge of the actual cost of a Pap test. Moreover, 42 percent of women who believed they had knowledge of the cost of a Pap overestimated the cost by at least $10, with nearly one in five overestimating the cost by over $60. Using less conservative estimates around the actual medical cost of a Pap test as reported by Medicare, these overestimates and the proportion of women who overestimated Pap test cost would be even greater.

While our findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating cost as a barrier to preventive screenings,17–20 our findings suggest that lack of knowledge about the actual cost of Pap tests may magnify the perception of cost as a barrier. Women who initially report not knowing the cost of Pap test were more likely to overestimate the cost when pressed for an answer.

Perceptions of cost as a barrier have also been associated with lack of insurance, a lower income level, and lower educational attainment, and our study results are consistent with this literature. For instance, lack of health insurance is often cited as a major barrier to all types of health care services.23,24 Not surprisingly, women in our study who lacked insurance were over 8.5 times more likely to report cost as a barrier to getting Pap tests compared to those with private insurance. This finding is in line with previous research that has demonstrated that costs and lack of insurance are barriers to access for preventive screenings among vulnerable populations.10,25,26 We found that the perception of cost as a barrier among these vulnerable women from Appalachia Ohio is related to lower utilization of cervical screening tests. Women in our study who believed that the cost of a Pap makes it difficult to receive one were twice as likely not to receive a Pap test within screening guidelines compared to those women who did not view cost as a barrier to getting a Pap test.

Another important consideration highlighted by these findings is that of the relationship between risk status and cost as a barrier to receiving a Pap test. While high-risk women were more likely to state that cost makes it hard for them to get a Pap test, it was also clear that many of these women were not aware of their actual risk status. Instead, 20% of women who were high risk reported perceiving themselves to be at lower risk than other women they know. Given inaccuracies in perceptions about both risk status and cost as a barrier, these findings are of great concern.

This study has limitations associated with both the population studied and the questions asked in the survey. First, this cross-sectional study is limited to the population of Ohio Appalachia, an area characterized by high levels of poverty and lower levels of educational attainment. Although this sample includes women from both urban and rural counties and may be generalized across other similarly underserved areas of the U.S., certain demographic features of this population such as a low proportion of minority residents may distinguish these results.

Another limitation can be attributed to the study design itself stemming from the fact that all women interviewed were linked to a clinic participating in the study. As this linkage provides evidence that all participating women had had clinic contact and thus access to care within the past two years, it is likely that our results are more favorable than they might have been if the study population also included women not affiliated with health clinics. Thus given our findings about the general lack of knowledge about Pap test costs and about cost as a barrier to Pap tests, it is likely that the level of knowledge among women who are not affiliated with a medical clinical might have been even lower.

Finally, this study only considered women’s perceptions of the direct medical costs of a Pap test. Other costs associated with the Pap test, such as transportation, child care, and unpaid time off are also important cost considerations that may affect women’s perceptions about the overall cost of a Pap test. Therefore, our results may underestimate the impact of cost as a barrier to Pap tests.

CONCLUSION

Given the potential for women’s perceptions to influence their motivation to seek cancer screening, addressing this knowledge barrier about Pap test cost is likely important. Efforts to increase Pap test use and reduce cervical cancer rates could focus on this specific population to increase awareness about tests costs, improve knowledge about cancer risk, increase Pap test utilization, and ultimately reduce the disproportionate burden of disease experienced among underserved women.

Acknowledgments

This research initiative is funded by the National Cancer Institute (P50 CA105632) and supported by the Behavioral Measurement Shared Resource at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Grant P30 CA016058 from the National Cancer Institute. The funding agency had no involvement in the development or submission of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation:

This research was peer-reviewed and accepted for two poster presentations: the 2008 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, June 8, 2008, Washington, D.C.; and the USC/NIH Conference: Interdisciplinary Science, Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Pasadena, California, May 3, 2007.

Disclosures: The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

No conflict of interest exists with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Healthy People. Healthy People. [accessed July 14, 2009];Objective 3–11: Increase the proportion of women who receive a Pap test. 2010 Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/document/html/objectives/03-11.htm.

- 2.Williams KP, Reiter P, Mabiso A, Maurer J, Paskett E. Family history of cancer predicts Papanicolaou screening behavior for African American and White women. Cancer. 2009;115:179–198. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonald C. Addressing disparities and the disproportionate burden of cancer. Cancer. 2001;91(suppl):195–198. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1+<195::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention and Early Detection Facts and Figures 2009. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2009a. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2009. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2009b. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedell GH, Rubio A, Maretzki A, et al. Community cancer control in a rural, underserved population: the Appalachian Leadership Initiative on Cancer Project. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2001;12:5–19. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall HI, Uhler RJ, Coughlin SS, Miller DS. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Appalachian women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lengerich EJ, Wyatt SW, Rubio A, et al. The Appalachia Cancer Network: cancer control research among a rural, medically underserved population. The Journal of Rural Health. 2004;20:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher JL, Engelhardt HL, Stephens JA, et al. Cancer-related disparities among residents of Appalachia Ohio. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2008;2(2):61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elnicki DM, Morris DK, Shockcor WT. Patient-perceived barriers to preventive health care among indigent, rural Appalachian patients. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:421–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coughlin SS, Thompson TD, Hall HI, Logan P, Uhler RJ. Breast and cervical carcinoma screening practices among women in rural and nonrural areas of the United States, 1998–1999. Cancer. 2002;94:2801–2812. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lantz PM, Weigers ME, House JS. Education and income differentials in breast and cervical cancer screening. Policy implications for rural women. Med Care. 1997;35:219–236. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, King JC, et al. Geographic disparities in cervical cancer mortality: what are the roles of risk factor prevalence, screening, and use of recommended treatment? Journal of Rural Health. 2005;21(2):149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chavez LR, Hubbell FA, Mishra SI, Valdez RB. The influence of fatalism on self-reported use of Papanicolaou smears. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:418–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shell R, Tudiver F. Barriers to cancer screening by rural Appalachian primary care providers. The Journal of Rural Health. 2004;20(4):368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Koo J, Hiatt RA. Cancer screening in public health clinics: the importance of clinic utilization. Med Care. 2001;32:1345–1351. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200112000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz ML, Wewers ME, Single N, Paskett ED. Key informants’ perspectives prior to beginning a cervical cancer study in Ohio Appalachia. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:131–141. doi: 10.1177/1049732306296507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAlearney AS, Reeves KW, Tatum C, Paskett E. Cost as a Barrier to Screening Mammography Among Underserved Women. Ethn Health. 2007;12(2):189–203. doi: 10.1080/13557850601002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAlearney AS, Whitney K, Tatum C, Paskett E. Perceptions of Insurance Coverage for Screening Mammography Among Women in Need of Screening. Cancer. 2005;103(12):2473–2480. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAlearney AS, Reeves KW, Dickinson SL, et al. Racial Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening Practices and Knowledge Within a Low-Income Population. Cancer. 2008;112(2):391–398. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paskett ED, McLaughlin JM, Reiter JL, et al. Psychosocial predictors of adherence to risk-appropriate cervical cancer screening guidelines: A cross sectional study of women in Ohio Appalachia participating in the Community Awareness Resources Education (CARE) project. Prev Med. 2010;50(1/2):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow SL. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasper JD, Giovannini TA, Hoffman C. Gaining and losing health insurance: strengthening the evidence for effects on access to care and health outcomes. Med Care Res Rev. 2000 Sep;57(3):298–318. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700302. discussion 319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Coverage matters: Insurance and health care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg A, Zaslavsky AM. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284(16):2061–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breen N, Wagener DK, Brown ML, Davis WW, Ballard-Barbash R. Progress in cancer screening over a decade: results of cancer screening from 1987, 1992, 1998 National Health Interview Surveys. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(22):1704–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.22.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]