Abstract

Progress in understanding the pathophysiology of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) is dependent in part on the development and application of effective animal models that recapitulate key aspects of the disease. The objective was to produce an experimental model of AAA in rats by combining two potential causes of metalloproteinase (MMP) secretion: inflammation and turbulent blood flow. Male Wistar rats were randomly divided in four groups: Injury, Stenosis, Aneurysm and Control (40/group). The Injury group received a traumatic injury to the external aortic wall. The Stenosis group received an extrinsic stenosis at a corresponding location. The Aneurysm group received both the injury and stenosis simultaneously, and the Control group received a sham operation. Animals were euthanized at days 1, 3, 7 and 15. Aorta and/or aneurysms were collected and the fragments were fixed for morphologic, immunohistochemistry and morphometric analyses or frozen for MMP assays. AAAs had developed by day 3 in 60–70% of the animals, reaching an aortic dilatation ratio of more than 300%, exhibiting intense wall remodelling initiated at the adventitia and characterized by an obvious inflammatory infiltrate, mesenchymal proliferation, neoangiogenesis, elastin degradation and collagen deposition. Immunohistochemistry and zymography studies displayed significantly increased expressions of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in aneurysm walls compared to other groups. The haemo-dynamic alterations caused by the stenosis may have provided additional contribution to the MMPs liberation. This new model illustrated that AAA can be multifactorial and confirmed the key roles of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in this dynamic remodelling process.

Keywords: aneurysm, aorta, blood flow turbulence, experimental model, metalloproteinase, vascular injury

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are a potentially fatal disorder that screening studies have detected in 2–9% of the general population (Ernst 1993; Keller et al. 2000). Because of their silent nature, the likely sequelae of undiagnosed AAAs include rupture and sudden death (Tanaka et al. 2009). Degenerative diseases such as atherosclerosis have been traditionally associated with AAA; however, the underlying pathophysiology of the arterial dilatation process is not fully understood (Aoki et al. 2007).

Recent studies with both human tissue and animal models have contributed to a paradigm shift regarding this disorder, and AAA is now considered to be part of an important and dynamic remodelling process in the arterial wall (Osborne-Pellegrin et al. 1994; Longo et al. 2005). In fact, numerous studies conducted during the past decade have confirmed the significance of an inflammatory process in AAA, particularly related to an upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Nordon et al. 2009), especially MMP-2 (Osborne-Pellegrin et al. 1994; Freestone et al. 1995) and MMP-9 (Newman et al. 1994; Thompson et al. 1995). The key role of MMPs in AAA development is also strongly supported by data showing that synthetic MMP inhibitors (Holmes et al. 1996; Bigatel et al. 1999) and overexpressed recombinant TIMP-1 block aneurysm growth in a rat model (Allaire et al. 1998). However, much of the functional regulation of these MMPs and their contribution to extracellular matrix (ECM) proteolysis in AAA formation remain to be clarified.

In this study, we combined two potential causes of MMP secretion and activation – acute inflammation and blood flow turbulence – to create a novel experimental model of AAA. In isolation, these causes were insufficient to provoke arterial dilatation and aneurysms. When combined, significant MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion and activation occurred and worked in concert to promote elastin degradation, wall remodelling and aneurysm formation. The AAAs formed in this new experimental model show an extraordinary aortic dilatation ratio with similar morphology to human abdominal aneurysms in just 3 days and can help to clarify the role of these MMPs in the development and progression of AAA.

Material and methods

Experimental protocol and surgery

Male Wistar rats, weighing 150 g, were randomly divided into four groups: Injury, Stenosis, Aneurysm and Control (40/group). The Injury group received a traumatic injury to the external aortic wall. The Stenosis group received an extrinsic stenosis at a corresponding location. The Aneurysm group received both the injury and stenosis simultaneously, and the Control group received a sham operation. The animals were euthanized on days 1, 3, 7 and 15 to monitor the induction of aneurysms. The protocol was approved by the Committee on Animal Research of the University of São Paulo (number 167/2008).

With the animals under anaesthesia, the abdominal aorta was narrowed just below the diaphragm as described previously (Swynghedauw & Delcayre 1982; Rossi & Peres 1992; Prado et al. 2006). Briefly, after being exposed through a left flank incision, the aorta was constricted with a diameter dental bur diamond (Microdont Stevile number 3215) adapted to stainless steel, doubled over in an L-shape and placed over the aorta. A ligature of cotton thread was made around the bur, which was immediately removed, reducing the vessel lumen to the diameter of the probe (0.94 mm, as measured with a digital pachymeter). In Wistar rats with a mean weight of 150 g, the cotton thread ligature imposed a fixed geometry on the vessel wall about 80 ± 4% of stenosis (Figure 1). This was calculated using the following formula: Residual luminal area (%) = [(prestenotic luminal area − stenotic luminal area)/prestenotic luminal area] × 100, where prestenotic luminal areas were obtained 5 mm above the ligature region and the stenotic luminal areas were obtained in the ligature region throughout consecutive slices in plastic resin. Aortic images of six rats were captured with a microscopic system (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar Germany) with a video camera (Leica Microsystems Ltd, Heebrugg, Switzerland) and an online computer using Leica qwin software (Leica Microsystems Image Solutions, Cambridge, UK). This result was confirmed by previous studies in our laboratory (unpublished data), using probes of different diameters (Rossi & Carillo 1991; Rossi & Peres 1992; Prado et al. 2006).

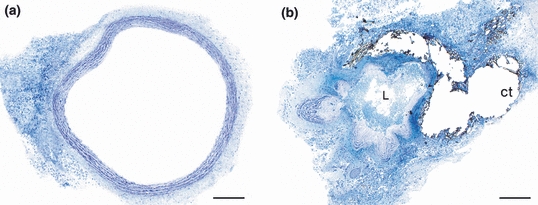

Figure 1.

Prestenotic luminal aorta (a) compared with the most stenotic luminal area (b). Note the extreme reduction of lumen (L) because of the ligature of the aorta with cotton thread (ct) (HRLM, Toluidine blue). Bar = 200 μm.

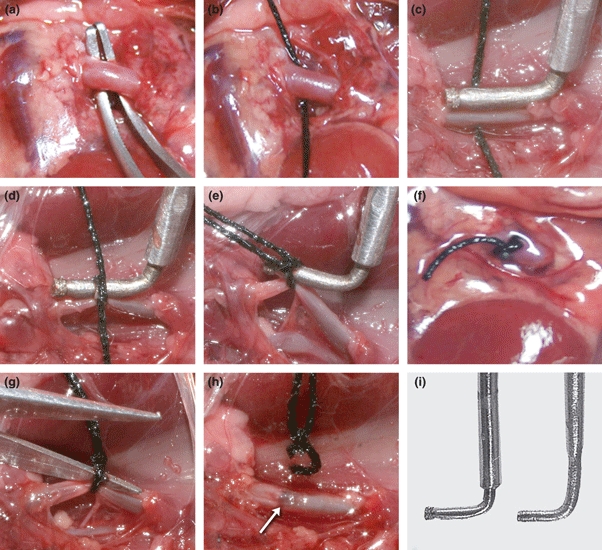

During its withdrawal, the rough end of the dental bur diamond induces a traumatic injury on the outside layer of the aorta; this is the Aneurysm group. If the vessel is made too narrow, the cotton thread ligature breaks during the withdrawal of the probe; if is too large, the vascular injury is not sufficient to trigger the development of the aneurysm. In the Injury group, the ligature was cut after the bur diamond was withdrawn. In the Stenosis group, a similar diameter dental bur without the rough end was used to avoid provoking vascular injury, and in the Control group, only the mobilization of the aorta was carried out. After this, the abdominal wall was sutured in peritoneal-muscle and skin planes. The photographic sequence of the model is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Photographic sequence of the surgical procedure used in the experiment. (a) Control group: only mobilization of the aorta was carried out; (a–f) Aneurysm group: after dissection, a dental diamond bur is placed over the aorta (c). A ligature of cotton thread is made around the bur (d), which is immediately removed (e), reducing the vessel lumen to the diameter of the probe (f); (a–h) Injury group: the ligature was cut after the bur diamond was withdrawn (g, h), provoking wall injury (arrow), and (i): At left, a stainless steel version of a dental bur diamond and at right the tool without the bur diamond.

Colour Doppler ultrasound

Aorta colour Doppler sonography of 3-days samples under xilazin and ketamin anaesthesia was performed, using a GE Healthcare Ultrasound System, Model Logic e (Milwaukee, WI, USA) with a multifrequential (6–12 MHz) linear array transducer with colour Doppler capability. The rats lay in the supine position. After ultrasound scanning of the aorta, colour Doppler was performed in the region of the aneurysms and the corresponding location in the others groups.

Macroscopic assessments, harvesting and preparation of aortas

Animals were anesthetized, and the abdominal aorta was exposed. The aneurysms’ median diameter was obtained by measuring the major and minor diameters with a digital pachymeter, which was performed by a single person (KMM). The dilatation ratio was calculated according to the following formula: Dilatation ratio (%) = [(aneurysmal diameter − aortic diameter)/aortic diameter] × 100. An AAA was defined to be when the dilatation ratio was >50% (Johnston et al. 1991).

The aortas were rapidly excised from the trunk down to the iliac bifurcation and washed at a pressure-perfusion of 100 mmHg with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) through the ascending aorta. The aneurysms were cut transversely into two equal parts. One segment was fixed with phosphate buffer plus 10% formalin for 1–2 min and immersed in the same fixative for 24 h at room temperature, and the remaining part was frozen for MMP-2 and MMP-9 assays. The corresponding aortic segments of the other groups were cut, fixed and processed similarly. In the Injury group, stereological microscopy was used to measure the extent of the injury to the aortic wall.

Histologically and morphometric analyses

Paraffin-embedded 5-μm-thick sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for general appearance, resorcine (RES) for elastin and picrosirius red (PSR) for collagen. Images of the sections were captured with a microscopic system (Leica Microsystems GmbH) with a videocamera (Leica Microsystems Ltd) and an online computer. For morphometric analyses, the images were assessed by a researcher blinded to the protocol design (KMM), using Leica qwin software (Leica Microsystems Image Solutions).

The thickness of the aneurysm/aortic wall was determined from the average thickness at 20 points of the cross-sectional aortic wall in the HE-stained sections. Areas of elastin and collagen in the cross-sectional aortic walls were determined by optical density in eight randomly chosen noncoincident fields at a magnification of 400×, giving a total area of 0.5 mm2. Thresholds for the elastic and collagen fibres were established for each slide after enhancing the contrast up to a point at which the fibres were easily identified. The means were calculated, and the values were expressed as a percentage (%). MMP-2 and MMP-9, inflammatory cells, neovessels and mesenchymal proliferation were counted in eight randomly chosen noncoincident fields of immunohistochemical slides, at a magnification of 400×, giving a total area of 0.5 mm2. The primary antibodies were MMP-2 (K-20, SC 8835; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), MMP-9 (C-20, SC6840; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), CD68 (clone ED-1, 1/100; Serotec Ltd., London, UK), CD20 (M-20, 1/100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), CD3 (MCA772, clone 1F4, 1/100; AbD Serotec Ltd., London, UK), α-actin (Smooth Muscle, clone 1A4, 1/100; Research Diagnostics, Inc., Concord, MA, USA) and CD31 (Rabbit Anti-CD31 Polyclonal Antibody, Unconjugated-250590; Abbiotec, San Diego, CA, USA). Neutrophils were counted in H&E slices. The means were calculated and the values were expressed per area (mm2).

Measurement of MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels by gelatin zymography

Gelatin zymography is one of the most commonly used methods for the quantification of MMP-2 and MMP-9. The enzymes are separated by molecular weight after gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions. The enzymes are then refolded and forms of the different molecular weight are visualized in zymograms (Rizzi et al. 2009). In this study, gelatin zymography of MMP-2 [form ‘latent’ or pro-enzyme form (72 kDa) and ‘active’ (64 kDa)] and MMP-9 (92 kDa) from aorta samples was performed as previously described (Osborne-Pellegrin et al. 1994; Gerlach et al. 2005; Ikonomidis et al. 2005; Souza-Tarla et al. 2005; Castro et al. 2008).

Briefly, frozen aorta samples were homogenized in extraction buffer (300 μl; 0.08 g of aorta sample) containing 10 mmol/l CaCl2, 50 mmol/l Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 1 mmol/l Phe (1,10 ortho-phenanthroline), 1 mol/l PMSF (phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride) and 1 mmol/l NEM (N-ethylmaleimide). The samples were placed on ice in the refrigerator for 20 h, to extract the proteins. They were centrifuged at 3000 g for 15 min. The protein content was measured by the Bradford method (Bradford 1976).

Samples were diluted in sample buffer (2% SDS, 125 mmol/l Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, and 0.001% bromophenol blue) and subjected to electrophoresis on 12% SDS–PAGE co-polymerized with gelatin (1%) as the substrate. After electrophoresis was completed, the gel was incubated for 1 h at room temperature in a 2% Triton X-100 solution, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 16 h in Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 10 mmol/l CaCl2. The gels were stained with 0.05% Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 and then destained with 30% methanol and 10% acetic acid. Gelatinolytic activities were detected as unstained bands against the background of Coomassie blue-stained gelatin. Enzyme activity was assayed by densitometry using a Kodak Electrophoresis Documentation and Analysis System (EDAS) 290 (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA). Gelatinolytic activities were normalized against an internal standard (foetal bovine serum), to allow for intergel analysis and comparison.

In situ zymography

Samples from day 3 were frozen in Tissue Tek® O.C.T. Compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA, USA) using isopentanol and liquid nitrogen. Glass slides (Super Frost) holding frozen unfixed control or DCM tissue sections (5 μm) were covered with a DQ gelatin substrate (E12055; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) diluted at 1:20 in Tris/HCl (50 mmol/l, pH 7.4) containing 10 mmol/l CaCl2. All steps were performed in the dark. Slides were incubated in humidified chambers at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, the DQ gelatin was washed off as follows: glass slides were rinsed five times with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and washed once with PBS. Slides were mounted with cover slips, visualized with fluorescence microscopy (Leica Imaging Systems Ltd., Cambridge, UK) and photographed using Leica videomicroscopy with the Leica qwin software in conjunction with a Leica microscope, video camera and on-line computer. Gelatinolytic activity was observed as areas of green fluorescence on a dark background.

Statistical analyses

The data were analysed using graphpad prism Software version 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The morphometric comparisons were made by one-way analysis of variance and Newman–Keuls’ posttest for multiple comparisons and were carried out with graphpad prism graphing and analysis software. The data are expressed as the means ± SD. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The surgical procedure in each group takes approximately 20 min. Technical failures involve total rupture of the aortic wall with voluminous haemorrhage, sometimes leading to intraoperative death.

External injury of the aortic wall

In the Injury group, the diamond end led to a traumatic injury of 40–50% of the aortic diameter, sometimes reaching half the thickness of the wall and breaking most of outsider elastic fibres (data not shown). An adventitial neutrophilic infiltration was observed on the first day, continuing weakly from the third to the seventh day and diminishing significantly by the fifteenth day. No significant aortic wall remodelling or dilatation was observed in this group. In the Stenosis group, in addition to the stenosis itself, the cotton thread ligatures compressed the aortic wall without evident fragmentation of elastic fibres (Figure 1b). A significant peri-adventitial gigantocellular inflammation was seen involving the cotton thread, but no aortic dilatation was observed in this group. The Control group showed no alterations.

Haemodynamic alterations inside the aorta because of stenosis

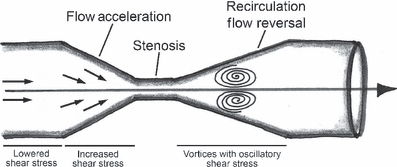

Similar models of arterial stenosis have estimated shear stress values from measurements of vessel diameter and blood flow velocity via Doppler measurements (Nesbitt et al. 2000; Cheng et al. 2006). Increased shear stress in the vessel segment inside the ligature, reduced blood flow, and consequent lower shear stress in the region upstream from the stenosis and a vortex downstream from the stenosis (oscillatory blood flow) were described. The downstream vortex is generated by a boundary separation immediately downstream of the stenosis, that is induced by a combination of acceleration of the blood at the beginning of the stenosis, the inertia of blood and the angle of the streamline at the end of the stenosis (Nesbitt et al. 2000; Cheng et al. 2006). A schematic view of these blood alterations is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the shear stress patterns induced by stenosis is show (Modified from Cheng et al. 2006).

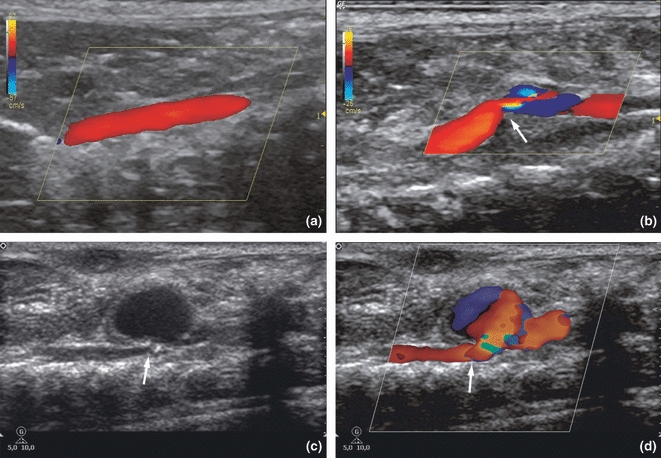

Colour Doppler ultrasound

Colour Doppler ultrasound showed laminar flow in the aortas of the Injury and Control groups: the dark red colour near the aortic wall represented a slower rate of laminar flow, whereas the spectrum of this laminar flow was characterized by a clear systolic window. Colour Doppler in the Stenosis group demonstrated preserved laminar flow that appeared dark-orange to yellow in the prestenotic segment and mixed colours characterizing turbulent flow in the poststenotic segment. In the prestenotic segment, the Doppler spectrum showed laminar flow with relatively low resistance, whereas spectral broadening, the hallmark of turbulent flow, was observed in the poststenotic segment. In the Aneurysm group, colour Doppler showed a very fast flow in prestenotic segments and mixed colours within the aneurysm, representing turbulent flow in the poststenotic segment. The Doppler spectrum of the poststenotic segment indicated slower flow compared to the prestenotic segment (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Colour Doppler: (a) Dark red near the aorta wall, representing laminar flow in the abdominal aortas from Injury and Control groups. (b) Stenotic group showing laminar flow, which appears dark-orange to yellow in the prestenotic segment and mixed colours in the poststenotic segment, indicating turbulent flow. The arrow points the stenosis in the aorta. Grey scale (c) and colour Doppler (d) of the (a) group on the third day. Note the abdominal aorta with a narrowing (arrows) is associated with a true aneurysm. The mixed colour within the aneurysm represents turbulent flow.

Macroscopic assessment and histology of the Aneurysm group

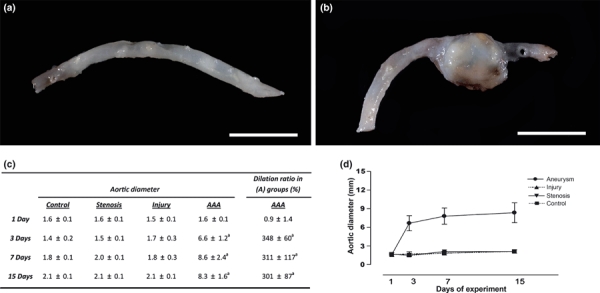

The Aneurysm group showed AAAs in 60–70% of the animals. Enormous AAAs were formed by day 3, located invariably at the previously injured-stenosed area in the abdominal aorta (Figure 5). The mean diameters were 1.6 ± 0.1 mm on the first day postsurgery (dps), reaching 6.6 ± 1.2 mm (P < 0.001) on the third dps, 8.6 ± 2.4 mm (P < 0.001) on the seventh dps and 8.3 ± 1.6 mm (P < 0.001) on the fifteenth dps. The statistical significance is relative to the other groups. The mean dilatation ratios of the AAAs were 348 ± 60 at 3 dps, 311 ± 117 at 7 dps and 301 ± 87 at 15 dps (Figure 5). When sectioned, the AAAs frequently showed fresh mural thrombi and/or thrombotic fragments inside the lumen. No mural thrombosis was observed in the others groups.

Figure 5.

Macroscopic view of the abdominal aortas: (a) Representative aortas from the Stenosis and Injury groups showing no abnormal dilatations, and (b) a large aneurysm with a dilatation ratio of more than 300% restricted to the previously injured-stenosed area observed on the third day in the Aneurysm group. Bar = 1 cm. (c) Table showing the mean aortic diameters of the groups (mm) and the dilatation ratio in the Aneurysm group during the experiment. (d) Change in aortic diameter during the experiment. The data are shown as the means ± SD (n=6 per group; a: P < 0.001).

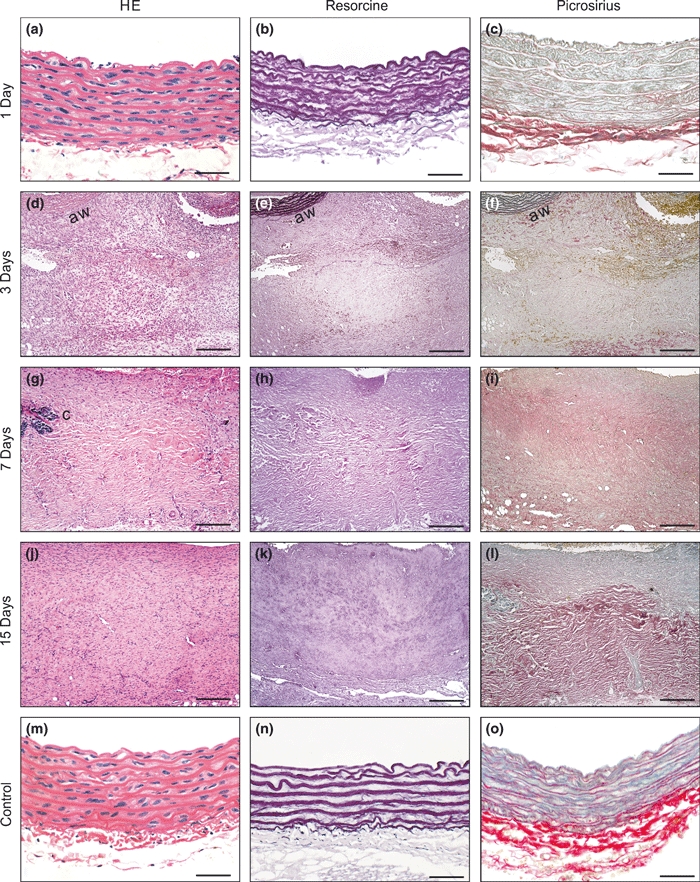

In the Aneurysm group, the aneurysm wall showed a modest adventitial neutrophilic infiltration on the first day. On the third dps, the aneurysm wall showed extensive structural remodelling characterized by degeneration of the extracellular matrix, intense mesenchymal cell proliferation, increased angiogenesis and abundant collagen deposition in all layers of the aortic wall. Importantly, there was massive elastic fibre destruction and fragmentation. These alterations were initiated in the outside layer of the aorta and were associated with an intense inflammatory response composed especially of neutrophils and macrophages, but also B and T lymphocytes and, occasionally, dispersed calcification foci. At 7 and 15 dps, the alterations were similar to those at 3 dps, except for greater wall thickness, slighter inflammatory infiltrate and neovascularization, and denser collagen deposition (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Microscopic views of the Aneurysm group at each experimental time point (a–l). On the first day, no significant alterations were observed. On the other days, extensive wall remodelling moving into the adventitial tissue was seen, characterized by degeneration of extracellular matrix, mesenchymal cell proliferation, increased angiogenesis and abundant collagen deposition progressing inward towards the whole aortic wall (aw). Note the massive elastic fibre destruction and fragmentation, prominent starting on the third day. Calcification foci (c) were seen. At 7 and 15 dps, the alterations were similar to those at 3 dps, except for the greater wall thickness, less inflammatory infiltration and neovascular formation, and apparently denser collagen deposition. Representative microscopic examples of the aortas of the Control, Stenosis and Injury groups without significant alterations are shown (m–o).Bar = 25 μm (a–c, m–o), 135 μm (d–l). Original magnification, 400×.

Morphometric analyses

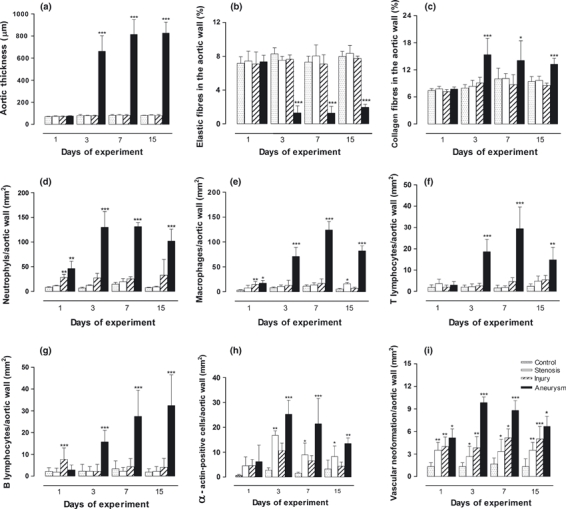

In the Aneurysm group, the mean aortic thicknesses were 75 ± 3.4, 661 ± 140 (P < 0.001), 814 ± 133 (P < 0.001) and 826 ± 99 μm (P < 0.001) at 1, 3, 7 and 15 dps respectively. The statistical significance is relative to the other groups. The median aortic thicknesses over all days in the other groups were 77.1 ± 6.3, 79.8 ± 4, 77.8 ± 5.2 and in the Injury, Stenosis and Control groups respectively (Figure 7a). Massive destruction of the elastic fibres in the Aneurysm group relative to the other groups was confirmed, measuring 7.3 ± 0.7, 1.2 ± 0.8 (P < 0.001), 1.2 ± 0.7 (P < 0.001) and 1.9 ± 0.3 (P < 0.001) on days 1, 3, 7 and 15 respectively (Figure 7b). The statistical significance is relative to the other groups. There was a more than 80% reduction of elastic fibres in the aneurysmal wall. The median number of elastic fibres over all days in the other groups was 7.3 ± 0.7, 7.8 ± 0.9 and 7.6 ± 0.6 in the Injury, Stenosis and Control groups respectively. In contrast, collagen fibres increased abruptly in the Aneurysm group relative to the other groups on the third day and remained higher in number until the fifteenth dps, with means of 7.7 ± 0.4, 15.3 ± 3.6 (P < 0.001), 14.1 ± 4.3 (P < 0.05) and 13.3 ± 1.3 (P < 0.001) on the first, third, seventh and fifteenth dps respectively (Figure 7c). The median collagen fibre numbers over all days in the other groups were 8.3 ± 1, 8.9 ± 0.9 and 8.6 ± 1.1 in the Injury, Stenosis and Control groups respectively.

Figure 7.

Bar graphs showing the changes in the different morphometric parameters analysed in all groups. Data shown are means ± SD (n=6 per group); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 [Aneurysm group vs. Control, Stenosis and Injury groups in a–c, f and g; Stenosis group vs. Control and Injury groups in e, h and i, and Injury group vs. Control and Stenosis groups in d, e and i].

The inflammatory response in Aneurysm group was transmural in distribution. Neutrophils were the predominant inflammatory cell in the aneurysmal wall, with significantly higher numbers on all days of the experiment, peaking on days 3 and 7 and declining on day 15 (Figure 7d). They measured 46.2 ± 14.9 (P < 0.01), 129.7 ± 31.9 (P < 0.001), 131.3 ± 8.2 (P < 0.001) and 101.8 ± 24.5 (P < 0.001) at 1, 3, 7 and 15 dps respectively. There was no significant neutrophilic infiltrate in the other groups [the medians varied between 9.2 ± 1.8 (Control group) and 12.9 ± 2.3 (Stenosis group), except on the first dps in the Injury group, where they were 28.2 ± 6.3 (P < 0.01)]. Macrophages were the second most prominent inflammatory cell in the aneurysmal wall and also had a transmural distribution, with a peak on day 7. They measured 17.2 ± 5.5 (P < 0.05), 70.8 ± 18.2 (P < 0.001), 124.2 ± 17.1 (P < 0.001) and 82.1 ± 10.1 (P < 0.001) at 1, 3, 7 and 15 dps respectively (Figure 7e). T lymphocytes showed a curve with a peak at the seventh day that decreased at day 15 with 3 ± 1.5, 18.6 ± 5.8 (P < 0.001), 29.4 ± 10.2 (P < 0.001) and 14.8 ± 5.8 (P < 0.001) on days 1, 3, 7 and 15 in the Aneurysms groups respectively (Figure 7f). In contrast, B-lymphocyte infiltration showed a progressive increase until the end of the experiment, with values of 2.8 ± 2, 15.7 ± 5 (P < 0.001), 27.5 ± 11 (P < 0.001) and 32.5 ± 14 (P < 0.001) in Aneurysms groups on days 1, 3, 7 and 15 respectively (Figure 7g). The statistical significance is relative to the other groups. There was no significant inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltrate in the other groups. The median macrophage, B- and T-lymphocyte numbers over all days of the experiment were 6.9 ± 4.5, 5.7 ± 2.4 and, 4 ± 1.7 for the Injury, Stenosis and Control groups respectively.

To detect mesenchymal cell proliferation, we counted α-actin-positive cells in the aortic walls of all the groups. No significant differences were seen on the first dps, when most displayed smooth arterial wall muscle cells (SMCs). However, the Stenosis group showed more α-actin-positive cells in the aortic wall than the Injury and Control groups, even without evident wall remodelling after the third dps (P < 0.01 to the third dps and P < 0.05 to the other days). The Stenosis group showed a median of 16.7 ± 1.8, 8.9 ± 4.7 and 8.2 ± 4.2 α-actin-positive cells numbers/mm2; the Injury group, 10.5 ± 3, 6.5 ± 2.1 and 4.3 ± 1.6, and the Control group, 2.7 ± 0.9, 1.5 ± 0.4 and 3.2 ± 2.6 at days 3, 7 and 15 (Figure 7h). In the Aneurysm group, we found the greatest numbers of α-actin-positive cells, usually in the form of myofibroblasts in the remodelling wall with values of 25.2 ± 5.6, 21.4 ± 10.2 and 13.5 ± 2.2 at 3, 7 and 15 dps respectively (Figure 7h). These results were significant relative to the other groups (P < 0.05). Neovascularization was observed in all groups. The Aneurysm group had the highest values of neovessels in the remodelling wall, with 5.1 ± 1.1, 9.8 ± 0.7, 8.8 ± 1.3 and 6.6 ± 1.3 on days 1, 3, 7 and 15 respectively. These values were different from the other groups (P < 0.05). New-formed blood vessels were seen in the adventitia of the other groups with 4 ± 1.2, 3.8 ± 1.4, 5.1 ± 1.1 and 5 ± 1.6 in the Injury group; 3.5 ± 1, 2.6 ± 1.3, 3.3 ± 1.6 and 3.5 ± 1 in the Stenosis group, and 1.3 ± 0.5, 1.3 ± 0.5, 1.6 ± 0.8 and 1.3 ± 1 in the Control group on days 1, 3, 7 and 15 dps respectively (Figure 7i). The differences were significant (P < 0.05) when comparing the Stenosis and Injury groups with the Control groups but were not significant between the Stenosis and Injury groups.

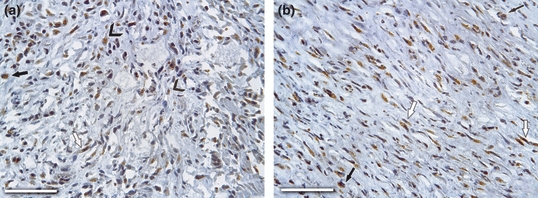

Immunohistochemical staining showed that MMP-9 was strongly expressed in the inflammatory cells, especially neutrophils and macrophages, but also in myofibroblasts and dispersed in the interstitium through the remodelling wall of the aneurysms (Figure 8a) starting on the third dps until the end of experiment. In the other groups, MMP-9 expression was observed on a smaller scale in inflammatory cells present in the peri-adventitial tissue. On the other hand, MMP-2 was strongly expressed throughout the remodelled wall, especially within myofibroblasts and macrophages on days 3, 7 and 15 in the Aneurysms group, but they were also dispersed in the interstitium after day 7 to a smaller degree (Figure 8b). In the other groups, MMP-2 was slightly expressed in the SMCs of the medial layer.

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemical localization of MMP-9 and MMP-2 in aneurismal wall on day 3 after surgery are show. (a) MMP-9 showed strong expression throughout the remodelling wall, especially within neutrophils (arrowheads), macrophages (arrow) and myofibroblasts (open arrow), and (b) MMP-2 were strongly marked in macrophages (arrows) and myofibroblasts (open arrows). Bar = 150 μm; Original magnification, 400×.

Metalloproteinase assays

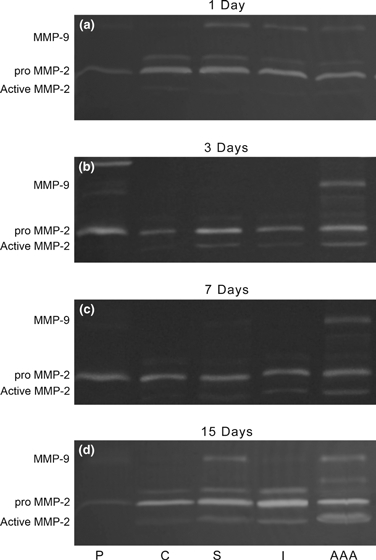

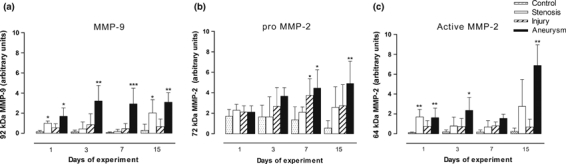

Gelatin zymograms were used to assess the gelatinolytic activities of MMP-9 and MMP-2 in extracts of aorta (Figure 9). Elevated levels of MMP-9 were observed in the Aneurysms groups compared to other groups starting at the first dps, showing an abrupt increase especially on the third dps and remaining elevated at similar levels until the end of the experiment (Figure 10a). The values of the Aneurysms groups were 1.7 ± 0.8, 3.2 ± 1.5, 3 ± 1.5 and 3 ± 0.9 on days 1, 3, 7 and 15 respectively. In the Injury and Stenosis groups, MMP-9 levels were slightly higher than in the Control group. The Stenosis group showed two smaller peaks on the first dps (compared to the Control group) and the fifteenth dps (compared to the Control and Injury groups) (P < 0.05; Figure 10a). The median values of MMP-9 over all days of the experiment were 0.6 ± 0.3, 0.9 ± 0.4, 0.2 ± 0.1 for the Injury, Stenosis and Control groups respectively. On the other hand, the latent and active forms of the MMP-2 changed progressively during the experiment. Latent MMP-2 (72 kDa) expression was significant after the seventh dps in the Injury and Aneurysm groups compared to the other groups (P < 0.05), but it continued to increase only in the Aneurysm group until the fifteenth dps (P < 0.01; Figure 10b). The mean values for Aneurysm group were 2.2 ± 0.6, 3.6 ± 0.8, 4.5 ± 1.8 and 5 ± 2 on days 1, 3, 7 and 15 respectively, whereas the media over all days were 3 ± 1.5, 2 ± 1 and 1.2 ± 0.8 for the Injury, Stenosis and Control groups respectively. Active MMP-2 (64 kDa) expression showed a similar behaviour to the latent form in the Aneurysm group, with significantly increased levels in most days of the experiment (P < 0.05 at day 3 and P < 0.01 on days 1 and 15) compared to the Injury and Control groups. However, the difference with the Stenosis group was not significantly different on the first day (Figure 10c). The Stenosis group showed higher values compared to Injury and Control groups (P < 0.01). The values for the Aneurysm group were 1.7 ± 0.9, 2.3 ± 1.3, 1.6 ± 0.4 and 7 ± 2 on days 1, 3, 7 and 15 respectively, whereas the means over all days were 0.8 ± 0.4, 1.5 ± 0.9 and 0.2 ± 0.1 for the Injury, Stenosis and Control groups respectively.

Figure 9.

Representative SDS–PAGE gelatin zymography of aortic samples (a–d), showing increased expression of MMP-9, identified as a 92 kDa band, and latent (72 kDa) and active forms (64 kDa) of MMP-2 in the aneurysms extracts (AAA) in all days after surgery. P, pattern; C, Control; S, Stenosis; I, Injury; AAA, Aneurysm groups.

Figure 10.

Bar graphs show the densitometric analyses of the MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities during the experiment. (a) Note the elevated levels of the MMP-9 in the Aneurysm group, starting at the first dps and remaining elevated at similar levels until the end of the experiment. (b) Pro-MMP-2 was significantly expressed after the seventh dps, especially in the aneurysms groups. (c) Active MMP-2 increased expression showed a similar behaviour to the latent form in the aneurysm group, with significant levels on most days of the experiment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 [Aneurysm group vs. Injury, Stenosis and Control groups (a–c); Stenosis group vs. Injury and Control groups (a, c) and, Injury group vs. Stenosis and Control groups (b)].

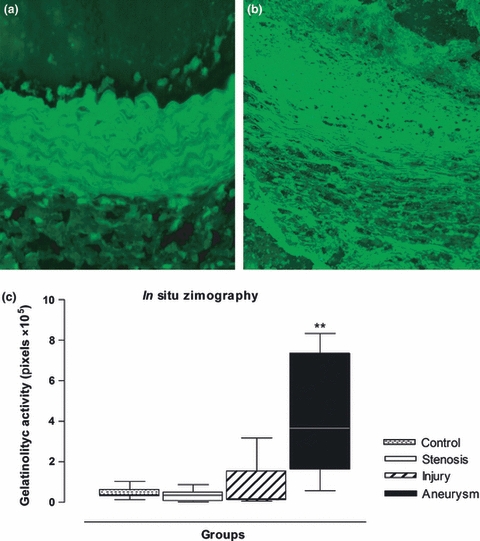

In situ zymography

In situ zymography revealed high gelatinolytic activity in the aneurysmal wall on the third day of the experiment, supporting the gelatin zymography and immunohistochemical results. Quantification of the fluorescent signal by area (independent of the size of the lesion) showed elevated gelatinolytic activity in the remodelling wall of the Aneurysm group compared with the Injury, Stenosis and Control groups on all days of the experiment (P < 0.001) (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Representative images of in situ zymography of the aortic wall as seen in the control group (a) and in the aneurysmal group (b) at 3 dps. Note the intense fluorescence (light green) indicating gelatinolytic activity and wall degradation (black areas) in the aneurysmal wall (b). Original magnification, 400×. (c) Boxplot of optical density by image analysis showing the intense gelatinolytic activity in the aneurysmal wall at the third day of the experiment. **P < 0.01 [Anerysm group vs. Control, Stenosis and Injury groups].

Discussion

Knowledge about the mechanism of AAA formations is incomplete, mainly because of the lack of an adequate animal model that closely mimics human pathology. There are usually advantages and disadvantages to each of the models used for AAA research. Rats have relatively low costs, permit the maintenance of large animal stocks, are relatively easy to handle have the larger sized vessels compared to mice, facilitating surgical manipulation and generating large amounts of experimental tissue (Tanaka et al. 2009; Trollope et al. 2010). On the other hand, the principal disadvantage is related to the lack of genetic manipulation. Nevertheless, AAA models in rats are frequently used, especially to model vascular injuries because of aortic inflammation and dilation. The most commonly used model uses pancreatic elastase to promote an inflammatory reaction in the aortic wall, leading to degradation of the elastic fibres and developing aortic dilatation (Anidjar et al. 1990). Another model is generated by bathing the abdominal aorta in vivo with a solution of calcium chloride (CaCl2), thus inducing calcium deposition, SMC apoptosis and media degeneration represented by disruption of elastic lamella (Basalyga et al. 2004). Recently, Tanaka et al. (2009) produced more prominent abdominal aneurysms in rats, using a combination of these models. Our model has a high success rate, rapid development of aneurysms, dilatation ratio of more than 300% and morphological similarity to human AAAs. Low cost, easy execution after gaining some experience and no use of chemical substances are more attractive features of this model. Moreover, the haemodynamic alterations inherent to the model give an excellent opportunity to monitor blood flow alterations within the lumen of the aneurysms and probably facilitate the development of mural thrombosis, which is not frequently described in other models. It would offer an opportunity to better elucidate the role of thrombi components in the remodelling process of aneurysmal wall. Finally, the abrupt transition between the aortic wall and the remodelling aneurysmal tissue will allow the understanding of new aspects of tissue bioengineering. Thus, we believe that this novel model can help to clarify many aspects of the pathogenesis of abdominal aneurysm formation and maintenance. The main aspects of the most commonly utilized models of AAA in rats are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Most commonly used experimental models of abdominal aneurysms of aortas (AAAs) induction in rats

| Elastase perfusion* | CaCl2 application†‡ | Elastase perfusion + CaCl2 application§ | Our model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development time | 2 Weeks | 2–4 Weeks | 4 Weeks | 3 Days |

| Dilation ratio | 50% | Minimum | 93% | 300% |

| Thrombus | Few | No | No | Frequent |

| Similarly to human AAA | Moderate | Low | High | High |

| Complexity of execution | Moderate | Moderate | High | Low |

| Cost | Higher | Higher | Higher | Lower |

Numerous human and experimental studies have confirmed the presence of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the aneurysmal wall (Anidjar et al. 1990). Their principal action seems related to the elastolytic activity and modulation of arterial wall remodelling (Yoshimura et al. 2005). In this model, MMP-2 and MMP-9 were elevated, but showed different patterns of behaviour during aneurysm development. The MMP-9 peak coincided with the inflammatory cell influx (especially neutrophils) and with the elastolytic activity burst, but interestingly seemed to remain active even after most of the elastic fibre degradation and inflammation had diminished on the fifteenth day after surgery. On the other hand, MMP-2 showed a progressive increase during the experiment, with the highest values on day 15, reinforcing the theory that even though these MMPs are interdependent (Longo et al. 2005), they may have different roles in wall remodelling. Therefore, much of the functional regulation of MMPs in AAA formation remains to be clarified. On the other hand, macrophages and T lymphocytes peaked at the same experimental interval, suggesting synergistic action, probably producing cytokines and chemokines with a direct impact on the remodelling process (Freestone et al. 1995; Longo et al. 2002). Moreover, progressive values of B lymphocytes during the experiment were a troubling finding in this AAA model. Most being of these findings are shown for the first time in an experimental model of AAA.

In an attempt to further understand the mechanisms that underlie aortic remodelling and dilatation in this new model, we added groups with only wall injury or stenosis. When isolated, these features were not able to induce aneurysms, although both presented peaks of increased values of inflammatory cells and MMPs during the experimental period. The mechanisms of this protective effect are not known, but we speculate that natural protease inhibitors (especially TIMPs – tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases) are able to impede aneurysm formation. This was corroborated by the abrupt appearance of an enormous aneurysm only on the third day after surgery (which was not present on the second dps; authors’ unpublished observations), suggesting that the MMP–TIMPs balance shifted towards proteolytic activity (Kadoglou & Liapis 2004). The effects of the MMP–TIMPs balance in this model also warrant further investigation.

The Injury group gives support to the paradigm of an ‘outside-in’ hypothesis, in which vascular inflammation initiated in the adventitia can progress inward towards the entire vascular wall (Freestone et al. 1995; Thompson et al. 1995; Patel et al. 1996; Longo et al. 2005; Maiellaro & Taylor 2007). It is well established that the structures that confer resistance to aneurysmal dilatation likely reside within the outermost aspect of the media and the adventitia, contributing to the success of this model (Maiellaro & Taylor 2007). On the other hand, although flow conditions clearly influence intramural vascular inflammation, the mechanisms underlying these influences remain incompletely understood (Carrell et al. 1999; Dobrin 1999). The narrowing of the artery seriously perturbs the overall laminar nature of the blood flow and generates complex zones of accelerating, decelerating and turbulent flow (Nesbitt et al. 2000; Cheng et al. 2006; Prado et al. 2006), promoting proinflammatory gene expression (Cheng et al. 2006). Shear conditions also regulate cytokine, chemokine and growth factor expression (Maus et al. 2002). Isolated peaks of MMPs in the Stenosis group appear to validate this. An optimization of an AAA model in pigs was recently describe; this model associated the effect of elastase on the aortic wall in combination with turbulent blood flow because of a stenosing cuff, reinforcing the theory that turbulent flow in the aorta lumen can have an essential effect on the increase of AAA (Molácek et al. 2009). Thus, we believe that our model has great potential for improving our understanding of the etiopathogenesis of AAAs, as well as for the study of new therapeutic possibilities in this pathology.

Conclusions

Many traditional theories of aneurysm pathophysiology have been set aside in favour of newly discovered MMP-mediated mechanisms; however, the critical sequence of elastin loss that permits aortic dilatation and aneurysm growth has not been identified. This new model illustrates that AAA may be multifactorial, confirms the key roles of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in this dynamic remodelling process and reinforces the belief that ability to develop new therapeutics and ultimately prevent vascular disease (especially AAAs) could lay in our understanding of the critical signals and events involved in the inflammatory cascades associated with vascular remodelling.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julio C. Matos for the technical photography assistance and Ligia B. Santoro for the excellent technical assistance. Simone G. Ramos and Marcos A. Rossi are investigators of CNPq. This study was supported by grants of FAPESP, CNPq and FAEPA.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- Allaire E, Forough R, Clowes M, Starchcr B, Clowes AW. Local over expression of TIMP-1 prevents aortic aneurysm degeneration and rupture in a rat model. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:1413–1420. doi: 10.1172/JCI2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anidjar S, Salzmann JL, Gentric D, Lagneau P, Camilleri JP, Michel JB. Elastase-induced experimental aneurysms in rats. Circulation. 1990;82:973–981. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.3.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki H, Yoshimura K, Matsuzaki M. Turning back the clock: regression of abdominal aortic aneurysms via pharmacotherapy. J. Mol. Med. 2007;85:1077–1088. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basalyga DM, Simionescu DT, Xiong W, Baxter BT, Starcher BC, Vyavahare NR. Elastin degradation and calcification in an abdominal aorta injury model: role of matrix metalloproteinases. Circulation. 2004;110:3480–3487. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148367.08413.E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigatel DA, Elmorc JR, Carey DJ, Cizlncci SG, Franklin DR, Youkcy JR. The matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor BB-94 lintits expansion of experimental abdontinal aortic ancuwsms. J. Vasc. Surg. 1999;29:130–138. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrell TWG, Smith A, Burnand KG. Experimental techniques and models in the study of the development and treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br. J. Surg. 1999;86:305–312. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro MM, Rizzi E, Figueiredo-Lopes L, et al. Metalloproteinase inhibition ameliorates hypertension and prevents vascular dysfunction and remodeling in renovascular hypertensive rats. Atherosclerosis. 2008;198:320–321. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Tempel D, van Haperen R, et al. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation. 2006;113:2744–2753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrin PB. Animal models of aneurysms. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1999;13:641–648. doi: 10.1007/s100169900315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst CB. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;328:1167–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304223281607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freestone T, Turner RJ, Coady A, Higman DJ, Greenhalgh RM, Powell JT. Inflammation and matrix metalloproteinases in the enlarging abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1995;15:1145–1151. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.8.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng L, Wang W, Chen Y, et al. Elevation of ADAM10, ADAM17, MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression with media degeneration features CaCl2-induced thoracic aortic aneurysm in a rat model. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2010;89:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach RF, Uzuelli JA, Souza-Tarla CD, Tanus-Santos JE. Effect of anticoagulants on the determination of plasmamatrixmetalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 activities. Anal. Biochem. 2005;344:147–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DR, Petrinec D, Wester W, Thompson RV, Reilly JM. Indomethacin prevents elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in the rat. J. Surg. Res. 1996;63:305–309. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidis JS, Barbour JR, Amani Z, et al. Effects of deletion of the matrix metalloproteinase 9 gene on develop-ment of murine thoracic aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2005;30:I242–I248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston KW, Rutherford RB, Tilson MD, Shah DM, Hollier L, Stanley JC. Suggested standards for reporting on arterial aneurysms. Subcommittee on Reporting Standards for Arterial Aneurysms, Ad Hoc Committee on Reporting Standards, Society for Vascular Surgery and North American Chapter, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. J. Vasc. Surg. 1991;13:452–458. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.26737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoglou NP, Liapis CD. Matrix metalloproteinases: contribution to pathogenesis, diagnosis, surveillance and treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2004;20:419–432. doi: 10.1185/030079904125003143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller JA, Weinberg A, Arons R, et al. Two decades of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: have we made any progress? J. Vasc. Surg. 2000;32:1091–1100. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.111691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo GM, Xiong W, Greiner TC, Zhao Y, Fiotti N, Baxter BT. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 work in concert to produce aortic aneurysms. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:625–632. doi: 10.1172/JCI15334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo GM, Buda SJ, Fiotta N, et al. MMP-12 has a role in abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. Surgery. 2005;137:457–462. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiellaro K, Taylor WR. The role of the adventitia in vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;75:640–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maus U, Henning S, Wenschuh H, Mayer K, Seeger W, Lohmeyer J. Role of endothelial MCP-1 in monocyte adhesion to inflamed human endothelium under physiological flow. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283:H2584–H2591. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00349.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molácek J, Treska V, Kobr J, et al. Optimization of the model of abdominal aortic aneurysm--experiment in an animal model. J. Vasc. Res. 2009;46:1–5. doi: 10.1159/000135659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt WS, Mangin P, Salem HH, Jackson SP. The impact of blood rheology on the molecular and cellular events underlying arterial thrombosis. J. Mol. Med. 2000;84:989–995. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman KM, Jean-Claude J, Li H, et al. Cellular localization of matrix metalloproteinases in the abdominal aortic aneurysm wall. J. Vasc. Surg. 1994;20:814–820. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(94)70169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordon IM, Hinchliffe RJ, Holt PJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Review of current theories for abdominal aortic aneurysm pathogenesis. Vascular. 2009;17:253–263. doi: 10.2310/6670.2009.00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne-Pellegrin MJ, Coutard M, Poitevin P, Michel JB, Levy BI. Induction of aneurysms in the rat by a stenosing cotton ligature around the inter-renal aorta. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 1994;75:179–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MI, Melrose J, Ghosh P, Appleberg M. Increased synthesis of matrix metalloproteinases by aortic smooth muscle cells is implicated in the etiopathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 1996;24:82–92. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(96)70148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado CM, Ramos SG, Alves-Filho JC, Elias J, Jr, Cunha FQ, Rossi MA. Turbulent flow/low wall shear stress and stretch differentially affect aorta remodeling in rats. J. Hypertens. 2006;24:503–515. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000209987.51606.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi E, Castro MM, Fernandes K, et al. Evidence of early involvement of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in lead-induced hypertension. Arch. Toxicol. 2009;83:439–449. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi MA, Carillo SV. Cardiac hypertrophy due to pressure and volume overload: distinctly different biological phenomena? Int. J. Cardiol. 1991;31:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(91)90207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi MA, Peres LC. Effect of captopril on the prevention and regression of myocardial cell hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis in pressure overload cardiac hypertrophy. Am. Heart J. 1992;124:700–709. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Tarla CD, Uzuelli JA, Machado AA, Gerlach RF, Tanus-Santos JE. Methodological issues affecting the determination of plasma matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 activities. Clin. Biochem. 2005;38:410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swynghedauw B, Delcayre C. Biology of cardiac overload. Pathobiol. Annu. 1982;12:137–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A, Hasegawa T, Chen Z, Okita Y, Okada K. A novel rat model of abdominal aortic aneurysm using a combination of intraluminal elastase infusion and extraluminal calcium chloride exposure. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009;50:1423–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RW, Holmes DR, Mertens RA, et al. Production and localization of 92-kilodalton gelatinase in abdominal aortic aneurysms: an elastolytic metalloproteinase expressed by aneurysm-infiltrating macrophages. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:318–326. doi: 10.1172/JCI118037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trollope A, Moxon JV, Moran CS, Golledge J. Animal models of abdominal aortic aneurysm and their role in furthering management of human disease. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.01.001. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura K, Aoki H, Ikeda Y, et al. Regression of abdominal aortic aneurysm by inhibition of c-Jun Nterminal kinase. Nat. Med. 2005;11:1330–1338. doi: 10.1038/nm1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]