Abstract

What role do cultural norms play in shaping individual behaviour and how does this relationship change with rapid socioeconomic development? While modernization and convergence theories predict a weakened relationship between culture and behaviour as individuals rely less on family and community members for economic opportunities, recent research suggests that such norms can persist and continue to influence behaviour. We explored this question in the context of Indonesia, asking whether cultural norms for age at marriage and post-marriage residence—as articulated by local ethnic-based laws and customs known as ‘adat’—influence actual marriage behaviour. We demonstrate that adat norms are strong predictors of marriage behaviours, both over time and net of large increases in educational attainment. Our results suggest more generally that ethnic-based nuptial regimes can be critical and persistent determinants of marriage behaviours even as societies rapidly develop.

Keywords: economic development, education, ethnic groups, Indonesia, marriage age, marriage patterns, nuptiality

Introduction

Nuptial regimes, including norms for marriage timing and post-marriage residence, shape household formation processes and family organization in critical ways (Hajnal 1982; Mensch et al. 2005). In societies where marriage marks the beginning of childbearing, marital timing is a key determinant of fertility (Heaton 1996). Patterns of post-marriage residence influence household size and labor and resource allocation (Cain 1978; Caldwell et al. 1983). The persistence of nuptial regimes over time reflects the extent to which societies rely on the family to accomplish productive and reproductive goals (Fussell and Palloni 2004; Thornton and Fricke 1987).

An ongoing debate in the marriage literature concerns the importance of culture (including norms and ethnic group identities) in reproducing and reinforcing nuptial regimes, and thereby in influencing family formation processes. On the one hand, recent research has emphasized the role of cultural norms in the transition to adulthood, including age at leaving home (Billari and Liefbroer 2007), age at marriage (Pramualratana et al. 1985), post-marriage residence (Hirschman and Nguyen 2002), and the productive and reproductive roles of young women (Fussell and Palloni 2004). At the same time, proponents of modernization and convergence theories argue that rapid socioeconomic development is eroding the influence of culture on family formation processes by altering the goals that culturally-influenced nuptial regimes previously supported. While it has been demonstrated that developing societies often witness marked changes in nuptial regimes, culture influences on marriage behaviour during periods of such dramatic change are less well understood.

In this paper, we considered the competing forces of modernization and cultural tradition in Indonesia, a country with remarkable ethnic diversity. Specifically, we asked whether cultural norms for age at marriage and post-marriage residence—as articulated by local ethnic-based laws and customs known as ‘adat’—influence actual marriage behaviour. We also asked whether this culture-behaviour relationship has persisted during Indonesia’s social and economic transformation in the latter part of the twentieth century. Our analysis offers three extensions to previous studies. First, in contrast to convergence tests comparing cross-national variation in Western Europe, we measure cross-cultural convergence of marriage behaviour within Indonesia, thus holding constant both a broadly shared national history and macroeconomic development process.

Second, we sidestepped the problems inherent in attributing persistent unexplained between-group variation in marriage behaviour to cultural differences. Instead, we used explicit measures of cultural norms about family behaviour to assess the contribution of culture to marriage, exploiting the historical importance of Indonesia’s adat system. Ethnographic and socio-political research suggests that adat law shapes many aspects of family life in Indonesia (Bowen 2001, 2003; Davidson and Henley 2007; Grace 2004; Idrus 2004; Sillander 2004), and that differences in adat customs have historically been associated with ethnic differences in family-related behaviours (Blackburn and Bessell 1997). Thus, while traditional norms for marriage behaviour exist in many settings, in Indonesia these norms are formalized in a meaningful way, providing a unique opportunity to measure norms as distinct from both observed behaviour and simple group classification.

Finally, we exploited the sustained macroeconomic development in Indonesia over the past several decades to examine the changing role of marriage norms across cohorts. We measured the marriage behaviour of adults born between 1935 and 1964 using rich data from the Indonesia Family Life Survey. The eldest respondents in our sample married just after the country gained independence from Dutch colonial rule, when mortality and fertility were high and educational attainment was limited. The youngest respondents began marrying in the mid-1980s, following two decades of dramatic growth in GDP, significant infrastructure improvements, and expansions in the educational and health care systems (Gertler and Molyneaux 1994). By comparing cohort differences in marriage behaviour, we assessed how socioeconomic change and culture interact to shape family formation behaviour.

Modernization, convergence, and family change

Family change in less-developed countries has often been characterized as a process of ‘modernization’ that attenuates variation in nuptial regimes by relocating labor and socialization outside of the family (Goode 1963). In settings where the family is the main locus of both economic production and socialization, nuptial regimes remain fairly stable, and the influence of cultural norms on marriage behaviours is strong. Rules for mate selection, residential arrangements, inheritance, and transfers at marriage can all shape expectations for the appropriate age at marriage (Caldwell et al. 1983; Malhotra and Tsui 1996). For example, age at marriage is generally later in societies (or subgroups) that expect a newly-married couple to establish its own household (Hajnal 1982).

Modernization may disrupt this stability in several ways: Industrialization increases work opportunities outside of the family. The development of formal insurance markets reduces reliance on extended family networks. Transportation improvements connect people physically, increasing interactions among people of different regions, ethnicities, and socioeconomic strata. The educational gains that accompany development are themselves an important mechanism for family change (Caldwell et al. 1983). Education reduces reliance on parents for economic opportunities, decoupling household formation processes and employment (Thornton and Fricke 1987; Yabiku 2005). Greater educational attainment traditionally increases the economic role of the younger generation within the family, resulting in greater autonomy in decision-making (Ghimire et al. 2006).

Modernization thus diminishes both the economic necessity of intergenerational relationships and the attendant transmission of traditional norms, including those related to marriage, household formation, and childbearing, that previously reinforced ethnic- and region-based distinctions in familial behaviour. A theorized by-product of the modernization process, therefore, is that disparate family formation patterns across diverse societies will converge on an increasingly homogenous set of characteristics: later marriage, choice-based marriage partners, nuclear family living arrangements, and fewer births.

In much of Asia, as in other settings, several studies have documented how these ‘modern’ developments affect marriage and family behaviours. Increased levels of education, industrialization and urbanization are indeed associated with later marriage and a diminished role of parents in spousal choice (Ghimire et al. 2006; Yabiku 2005). Marriage ages have risen across the region, particularly for women (Jones 2005), due in part to the growing importance of nonfamily experiences including employment, schooling, and media exposure (Ghimire et al. 2006; Yabiku 2005), and to the shift towards love matches and self-choice of spouses. Similarly, studies in Indonesia have documented the relationship between the recent gains in educational attainment (Deolalikar 1993) and delayed marriage (e.g., Gertler and Molyneaux 1994; Heaton 1996; Malhotra 1997; Singh and Samara 1996).

At the same time, other studies have questioned the universal applicability of the modernization perspective in explaining nuptiality trends, emphasizing instead the powerful role played by cultural heritage even in the face of dramatic expansions in education and standards of living. Examples include consanguineous marriage in Iran (Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2008), parental coresidence among young adults in Hong Kong (Ting and Chiu 2002), and marriage timing among different ethnic groups in Sri Lanka (Malhotra and Tsui 1996). In Southeast Asia, differences in family behaviour between ethnically Chinese and Malay populations have persisted, despite significant gains in education for both men and women (Hirschman and Teerawichitchainan 2003; Jones 2004). Among the Sundanese and Madurese of Indonesia, early marriage remains the norm in rural areas despite increases in both educational and economic opportunities for women (Jones 2001).

Many studies, then, reject the notion that the world’s societies are converging to a homogenous nuptial regime, arguing that both modern and traditional forces shape nuptial behaviours in contemporary less-developed settings. Few studies, however, have been able to explicitly examine how these two processes interact. In one notable exception, Cherlin and Chamratrithirong (1988) demonstrate how economic development may reinforce traditional nuptial regimes by encouraging the involvement of parents in spousal choice, while simultaneously undermining these traditions by providing opportunities for women outside of the household. Their analysis of Thailand suggests that marriage patterns will grow more complex with development, not simply shift from traditional to modern models.

The dearth of literature examining the interplay of these two forces may stem from the difficulty of measuring cultural norms in a meaningful way. Previous udies have aggregated individuals’ reported attitudes and then related that aggregation to those same individuals’ behaviour (Butler 2002; Teitler and Weiss 2000), or have used observed behaviours as evidence of norms (Billy et al. 1994). Yet for our outcomes of interest, reports from respondents who have already made demographic behavioural decisions are by definition selected on the outcome. Furthermore, observed behaviour is an inadequate measure of the existence of norms (see Marini 1984). In this study we measured ethnic variation in tradition and cultural norms by using variation in Indonesian adat law.

The Indonesian setting

Adat law

Indonesia boasts extraordinary ethnic diversity and more than 250 spoken languages (see Hugo et al. 1987, pp. 18–24). The ethnic and linguistic composition of the country is mirrored in the diversity of adat systems throughout the archipelago. The term ‘adat’ broadly refers to customs, traditions, rules, or practices that guide social life and decision-making in Indonesian communities (Bowen 2003; Davidson and Henley 2007; Taylor 2003). These ethnic-based legal systems outline obligations and expectations for social and economic relationships, including marriage, inheritance, land-holding, and dispute resolution. Adat has a long history in Indonesia, dating back well before the Dutch colonial system organized the region into 17 different geographic ‘adat law areas.’ Nevertheless, a precise definition of adat and what it represents in Indonesian social life remains elusive. A classic volume on adat claims that ‘although comparisons are dangerous, the nearest analogy in our own societies is with prescriptions’ (Hooker 1978, p. 54).

Our goal in this study was to assess how the cultural prescriptions related to marriage embodied in adat systems—as asserted by adat experts themselves—shape actual marriage behaviour over time. A complete treatment of the intricacies of adat is beyond the scope of this study but we highlight two features of adat systems that are particularly relevant for our research goals (see Bowen 2001; Bowen 2003; Davidson and Henley 2007; Hooker 1978; Sillander 2004; and Ter Haar 1948 for more details).

First, adat is notable for its simultaneous authority and fluidity (Hooker 1978; Sillander 2004). For example, Sillander (2004) finds that most Bentians, an ethnic group on Borneo, claim adat as an important source of authority for resolving conflicts or determining social obligations. At the same time, adat itself is quite fungible: Bentians frequently argue about what constitutes correct interpretations of adat and may in fact interpret adat to suit a specific circumstance. Sillander calls adat a ‘frame’ [p.290] that Bentians may or may not choose to place around a decision, or action.

A second important point is the salience of adat legal systems in Indonesian village life even as the state has promoted a homogenous village structure that runs counter to many adat-based structures (Kato 1989), and as Islamic law has grown in importance (Grace 2004). This three-way tension between adat, state, and religious legal systems emerged during the colonial period and remains relevant today (Abdullah 1966; Bowen 2001, 2003; Davidson and Henley 2007; Sillander 2004; Spyer 1996). Both the Dutch colonial government and the post-Independence New Order government promoted adat as an important cultural institution but also sought to limit adat legal authority in matters related to property rights and dispute resolution (Bowen 2001; Sillander 2004). Following the 1979 Law on Village Administration, villages across Indonesia were set up to function essentially along the Javanese ‘desa’ or village model (Kato 1989). Researches have observed that in places where the desa structure is in conflict with the reality of the local adat structure, adat can still persist as a source of identity, authority, and adjudication (Abdullah 1966; Bowen 2003; Kato 1989; Kling 1995).

Laws concerning minimum marriage ages and other aspects of marriage (such as divorce and polygyny) are a particularly relevant example of this tension between adat law, state law, and Islamic shari’a law. During the colonial period, the Dutch assumed that adherence to adat law was driving high rates of child marriage, but were reluctant to impose marriage age restrictions that violated both adat and Islamic law, instead hoping that rising educational attainment would itself weaken the force of adat (Blackburn and Bessell 1997), a hypothesis we test below.

The post-colonial state took a stronger stand asserting national authority over both adat and Islamic law with 1974 legislation aimed at significantly restricting child marriage and curtailing arbitrary divorce and polygyny, though recent research suggests it had little direct influence on the age at marriage (Blackburn and Bessell 1997; Cammack et al. 1996; Jones 2001). This may be due in part to continued adherence to adat norms for marriage ages. In a study of adat marriage patterns among the Sasak, Grace (2004) contends that interpretations of both Islamic law and state law related to marriage are often shaped by local adat.

Indonesian nuptial regimes

Age at first marriage has traditionally been low in Indonesia, particularly for women (Jones 1994, 2001). While Jones (2005) identifies a recent ‘flight from marriage’ across Asia, early marriage is still more common and marriage more universal in Indonesia than in other Asian countries. Between 1960 and 2000, the percentage of Indonesian women unmarried at ages 30–34 grew from 2.2 to 6.6 per cent, though the level remains lower than comparable figures from other Southeast Asian countries (Jones 2005). In recent decades the median age at first marriage for Indonesian women ages 15–49 has risen from 20 in 1971 to 23 in 2000 (CBS Indonesia 2003). Among some ethnic groups, however, the median age at first marriage is still well below 18, even for women born 1966–1970 (Jones 2001, 2004).

Intergenerational co-residence in Indonesia is closely associated with land and property inheritance, norms for child care and old-age support, and decisions about the timing of fertility. Accordingly, there is a considerable diversity of ethnic norms for location of post-marriage residence (virilocal, uxorilocal, ambilocal and neolocal) and for the duration of stay in the first post-marriage residence. Ethnographic accounts demonstrate this diversity: the Kantu, Toba Batak and Karo Batak follow the pattern of a brief parental coresidence after marriage with the eventual goal of forming a new household (LeBar 1972; Sulistyawati et al. 2005). A Buginese couple will live in the wife’s parents’ house until a younger sister is married, then form a new household (Millar 1989). The Bentian tribe studied by Sillander (2004) is ambilocal, which usually means an uxorilocal period followed by a virilocal period. Balinese couples are almost universally virilocal. Among the Javanese, the nuclear family tends to be the preferred norm, although high status families may live in extended households (Boomgaard 2003).

Adat and marriage behaviour

A few previous studies have implicitly proposed a role between adat, or cultural variation more broadly, and nuptial regimes. Hull’s (2003) work on rapid changes in family size and structure in Indonesia notes that even when prescribing national norms for family size and composition, the Government of Indonesia must contend with local customs regarding de facto unions and bride price negotiations. Among the Bugis,Idrus (2004) claims that adat is still a lens through which marriage customs are viewed. Idrus notes that parents in Kulo still hold an ‘ideal’ age at first marriage of 15–17 years (an adat custom), despite the realities of expanded education and employment opportunities that are pushing marriage ages higher. Sillander (2004) reports that while the length of post-marriage coresidency with parents is usually determined by family negotiations and practical logistics, most Bentian villagers were also able to identify norms for these durations. In identifying possible explanations for the slow rise in Indonesia’s marriage ages, Jones (2007) acknowledges that in Indonesia, more than in other Southeast Asian countries, the social controls of the village are still strong. We argue that adat is a conduit through which this control is exercised.

We have built on this previous work by attempting to measure whether adat is explicitly related to marriage behaviours in contemporary Indonesia, and how economic development moderates this relationship. Given recent economic and education changes, we would expect a significant weakening of the intergenerational transmission of marriage behaviours, and thus would expect to see a convergence of behaviours between ethnic groups. However, scholars of marriage and family life in Indonesia have recognized the importance of cultural factors, conceptualized here as adherence to adat norms.

Our analysis, then, considered three questions: 1) whether ethnic-based prescriptions for marriage timing and residence predict actual marriage behaviour for birth cohorts entering into marriage during a period of rapid social and economic change; 2) whether the predictive power of ethnic based marriage prescriptions change by birth cohort over this period and 3) whether the attainment of secondary schooling moderate adherence to ethnic-based marriage prescriptions.

Data and methods

Our data come from the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS), first fielded in 1993, which sampled 7,200 households in thirteen Indonesian provinces. The second and third waves, IFLS2 (1997) and IFLS3 (2000) successfully re-interviewed over 94 per cent of initial IFLS households, including ‘split-off’ and relocated households (Frankenberg and Karoly 1995; Frankenberg and Thomas 2000; Strauss et al. 2004; Thomas et al. 2001). The survey collected detailed household- and individual-level data, including marriage and education histories for both men and women. At the community level, IFLS included interviews with village leaders and, in 1997, with experts in local adat law and customs.

Adat diversity

A unique feature of the 1997 Indonesia Family Life Survey was interviews with adat experts from 273 villages. In villages where one ethnic group comprised at least 50 per cent of the population and in a handful of villages with no ethnic majority, village heads were asked to identify local adat experts. Identified adat experts were then interviewed about the importance of adat locally and about adat customs related to marriage, divorce, elder care, and decision-making. For each question about local laws and customs, adat experts provided two responses: a response ‘according to traditional law’, and a response intended to capture ‘common practice now’.

Table 1 presents results from two questions related to marriage used in our analysis. Responses are shown for adat experts from ten of the major Indonesian ethnic groups, ordered by the number of adat experts interviewed in the IFLS2. This ranking approximates the relative size of the ethnic groups represented in the IFLS.

Table 1.

Marriage norms by ethnicity as reported by adat (ethnic law) experts, Indonesia, 1997.

| Acceptable age at marriage, mean (SD) | Post-marriage residence of couple, % | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| According to traditional law |

Common practice now |

According to traditional law |

Common practice now |

||||||||

| N | Female | Male | Female | Male | Virilocal | Uxorilocal | Ambilocal/ neolocal |

Virilocal | Uxorilocal | Ambilocal/ neolocal |

|

| Javanese | 118 | 16.3 | 20.3 | 18.9 | 22.9 | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.52 | 0.35 |

| (2.9) | (3.6) | (1.8) | (3.1) | ||||||||

| Sundanese | 39 | 15.7 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 22.1 | 0.10 | 0.64 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.51 | 0.41 |

| (1.7) | (2.4) | (2.4) | (3.0) | ||||||||

| Balinese | 15 | 19.9 | 22.9 | 21.1 | 24.7 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.47 |

| (2.5) | (3.4) | (2.3) | (4.1) | ||||||||

| Banjar | 11 | 15.6 | 18.0 | 18.4 | 20.6 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| (1.9) | (3.1) | (2.1) | (2.8) | ||||||||

| Batak | 10 | 18.3 | 21.5 | 21.0 | 24.6 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| (2.0) | (3.0) | (2.3) | (3.3) | ||||||||

| Betawi | 9 | 16.4 | 19.2 | 20.2 | 23.3 | 0.22 | 0.67 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.33 |

| (2.2) | (2.4) | (2.9) | (2.9) | ||||||||

| Sasak | 9 | 16.6 | 18.1 | 19.0 | 21.7 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| (1.6) | (2.9) | (1.2) | (2.5) | ||||||||

| Minangkabau | 7 | 18.6 | 21.7 | 19.0 | 21.4 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| (1.8) | (2.8) | (2.5) | (2.9) | ||||||||

| Bugis | 6 | 14.8 | 16.7 | 18.7 | 20.8 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.17 |

| (1.7) | (3.2) | (1.5) | (2.3) | ||||||||

| Madurese | 5 | 16.0 | 18.4 | 17.0 | 19.4 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.00 |

| (3.4) | (3.9) | (1.6) | (4.8) | ||||||||

Source: Indonesia Family Life Survey (1997)

After the sample size, the next four columns show the mean reported acceptable age at first marriage for women and for men, according to both ‘traditional law’ and ‘common practice now’ responses. Traditional minimum marriage ages vary widely across ethnic groups—for women, the range is from 14.8–19.9 years; for men, 16.7–22.9 years, with the Bugis and Balinese bracketing both ranges. In most cases the age at marriage reported as ‘common practice now’ is at least two years older than the traditional law response, suggesting that the traditional custom reported by the adat reflects a salient norm distinct from the contemporary marriage behaviour observed by the adat experts.

In the next six columns, the adat experts report the traditional custom and current practice for post-marriage residence. While adat experts from some ethnic groups almost universally report virilocality (e.g., the Batak), others report a strong norm for uxorlocality (e.g., the Minangkabau). Despite some inter-ethnic variation in reported norms for post-marriage residence, there is a clear modal response for all ethnic groups except the Madurese. The post-marriage residence variable shows less difference between traditional law and common practice than the age at marriage norms.

To what extent can we assume that these collated responses from adat experts truly represent salient norms for Indonesian adults? We justify our use of the IFLS adat expert interviews as a source of cultural norms about marriage in three ways. First, we note that the data presented in Table 1 are consistent with the ethnographic sources on Indonesian nuptial regimes discussed above. Second, we argue that the distinction made in the adat interview question format between traditional practices and current practices supports the notion of recognized traditional norms that are easily articulated by adat experts. Third, we rely on the unique status of adat in Indonesian society. While most societies lack a formal system of cultural authority with which to explicitly define cultural norms, Indonesia’s adat systems make this possible. Indeed, IFLS adat interviews have been used to identify cultural norms (as distinct from observed behaviours) in studies of daughter preference (Levine and Kevane 2003), aging and intergenerational transfers (Frankenberg, Chan et al. 2002; Frankenberg, Lillard et al. 2002), and social capital (Miguel et al. 2005, 2006). Thus, while adat is undoubtedly a difficult phenomenon to capture in a meaningful way for population research, we contend that the variation in adat respondents’ reports corresponds to variation in the norms about nuptial behaviour experienced by Indonesians transitioning into adulthood.

Marriage behaviour and secondary education

To look at changes in marriage behaviour over time, we sampled ever-married adults ages fifteen and older in the 1997 IFLS. Sampling only ever-married adults may introduce bias by ignoring the future behaviour of unmarried adults. Because marriage in Indonesia is nearly universal, this poses less of an issue in our analysis. Among those born between 1935 and 1964, over 98 per cent of older birth cohorts and over 90 per cent of the youngest cohort were married by 1997. Nevertheless, we developed a test of the sensitivity of our results to these few unmarried individuals (described below). We chose to exclude respondents born before 1935 to limit survival bias and to maximize accurate recall of marriage dates and post-marriage residence.

Marriage histories were used to construct a continuous measure of age at first marriage and a categorical measure for first post-marriage residence: 1) virilocal (with male’s parents), 2) uxorilocal (with female’s parents), or 3) on their own or with others. The last category reflects a combination of several possible responses but was dominated by respondents reporting living ‘on their own’. While there is some disagreement within couples in the first post-marriage residence reported, results presented below are robust to using either the husband’s or the wife’s response.

From the IFLS education histories we created a dichotomous measure of whether the respondent has any secondary schooling. Matriculation to secondary schooling was the key education decision for most Indonesian families in our sample. This measure was not designed to capture education as a competing risk for marriage, but rather to represent the difference between respondents who experienced the potential shift in attitudes and decreased reliance on the family that come with secondary schooling, and those who did not.

Descriptive statistics for the sample of 8,098 ever-married adults with complete information on age at marriage, education, and ethnicity are shown in Table 2 by cohort (Panel A) and by ethnicity (Panel B). Ethnicity of respondents in IFLS was determined by the IFLS team based on knowledge of languages other than Indonesian, language used in the interview, residence, birthplace, and name. Both marriage ages and secondary school attendance have increased across cohorts, more noticeably for women than for men. By ethnic group (Panel B), there is also noticeable variation in average marriage ages (almost five years for women and more than two years for men) and in secondary school attendance.

Table 2.

Age at marriage and secondary school attendance by cohort and ethnicity, married Indonesian adults ages 32–67, 1997 [N=8,098].

| Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at marriage, years | Attended some secondary school |

N | Age at marriage, years | Attended some secondary school |

N | |||

| Mean | SD | % | Mean | SD | % | |||

| Total sample | 18.2 | 5.2 | 18 | 4,277 | 23.1 | 5.1 | 31 | 3,821 |

| A. By cohort | ||||||||

| Born 1935–1939 | 17.5 | 5.4 | 7 | 457 | 22.7 | 5.5 | 22 | 424 |

| Born 1940–1944 | 18.0 | 5.4 | 10 | 664 | 23.5 | 5.6 | 22 | 506 |

| Born 1945–1949 | 18.2 | 5.2 | 16 | 529 | 23.2 | 5.0 | 30 | 508 |

| Born 1950–1954 | 18.2 | 5.5 | 18 | 726 | 22.8 | 4.8 | 34 | 693 |

| Born 1955–1959 | 18.5 | 5.0 | 22 | 861 | 23.1 | 5.1 | 34 | 825 |

| Born 1960–1964 | 18.3 | 4.7 | 25 | 1,040 | 23.2 | 4.7 | 35 | 865 |

| B. By ethnicity (10 largest ethnic groups) | ||||||||

| Javanese | 18.2 | 5.2 | 18 | 2,005 | 23.3 | 4.9 | 29 | 1,788 |

| Sundanese | 17.4 | 4.8 | 18 | 594 | 22.6 | 4.9 | 32 | 540 |

| Minangkabau | 19.4 | 4.3 | 38 | 270 | 24.1 | 5.3 | 48 | 246 |

| Balinese | 19.6 | 5.4 | 13 | 213 | 23.8 | 5.3 | 30 | 195 |

| Banjar | 16.8 | 5.1 | 13 | 168 | 22.4 | 5.6 | 28 | 163 |

| Bugis | 17.9 | 5.9 | 9 | 191 | 21.8 | 5.8 | 17 | 135 |

| Maduranese | 18.0 | 5.6 | 6 | 173 | 22.0 | 6.0 | 14 | 138 |

| Batak | 21.4 | 4.1 | 36 | 152 | 23.7 | 3.9 | 57 | 135 |

| Sasak | 19.0 | 5.5 | 6 | 155 | 22.7 | 5.7 | 24 | 129 |

| Bima | 20.0 | 4.1 | 13 | 66 | 23.7 | 3.9 | 25 | 64 |

Source: Indonesia Family Life Survey (1993, 1997)

Post-marriage residence

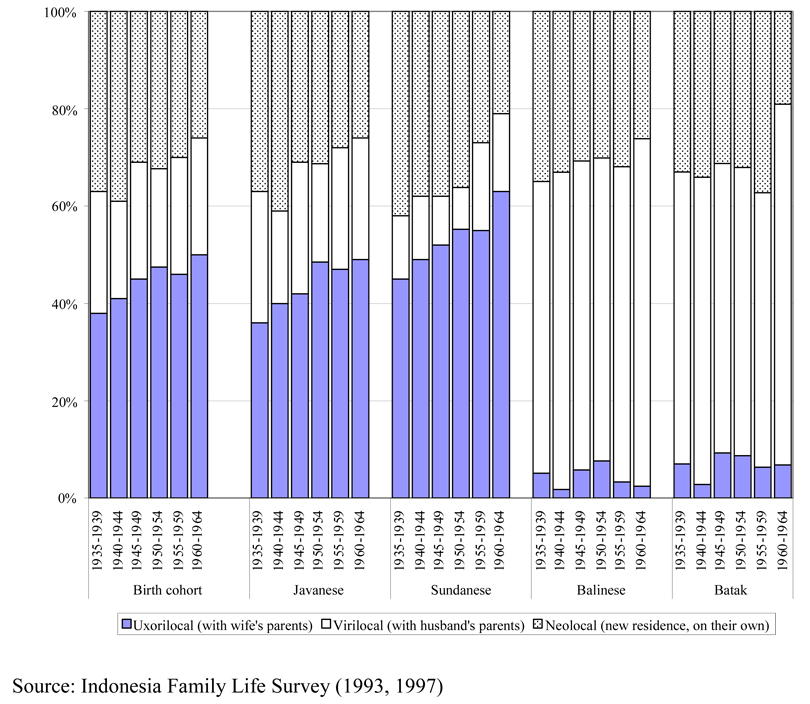

Post-marriage residence was our second outcome of interest. Figure 1 shows the distribution of post-marriage residence for ever-married Indonesian adults ages 33–62 in 1997. The first set of bars includes all ethnicities. Living with the female’s parents is the most common situation of the youngest cohorts, though significant proportions also live with the male’s parents or on their own. The graph shows fewer couples living on their own among the younger cohorts than among the older cohorts.

Figure 1.

Post-marriage residence by ethnicity and birth cohort for ever-married Indonesian adults ages 33–62, 1997 [N=7,549].

The remaining sets of bars show post-marriage residence by cohort for the adults included in our analytic sample for four of the larger ethnic groups, chosen to demonstrate both uxorilocal patterns (Javanese and Sundanese) and virilocal patterns (Balinese and Batak). The uxorilocal practice is more pronounced for the Sundanese than for the Javanese, and appears to have become increasingly common over time. Virilocality among the Balinese and Batak groups is almost universal with slight increases in recent cohorts.

Predicting marriage behaviour from adat norms

The key independent variables in our analyses were the adat norms for traditional age at marriage and for traditional post-marriage residence. Here we sought to capture the prevailing cultural norms to which respondents were exposed in the years before marriage. We first calculated ethnicity-specific averages in the reported traditional age at marriage for women and for men. For example, if two adat experts from the same ethnic group reported a traditional age at marriage for women of 16 and 17 respectively, then we assigned a traditional age at marriage of 16.5 to all women in that ethnic group. (Models using the median and modal adat responses produced similar results). While undoubtedly an oversimplification of adat diversity, this approach accomplished our goal of capturing population variation in the norms experienced by young adults; thus while the ‘norm’ for age-at-marriage is unlikely to be exactly 16.5 for a specific ethnicity, we argue that adolescents from an ethnic group in which the adat responses cluster around 16 and 17 are exposed to different norms than those from ethnic groups in which responses cluster around 19 and 20.

To capture the expectation for post-marital residence of the couple, we used the modal response from the adat experts (by ethnic group) when asked whether newlyweds traditionally live with the female’s parents, with the male’s parents, or on their own or with others. ‘On their own or with others’ was not the modal response for any ethnic group, so the final version of this variable was dichotomous. We again calculated the ethnicity-specific norms from the adat responses and assigned the values to all individual respondents of the same ethnic group.

It is important to note that all adat expert interviews took place in 1997; however, we assigned these adat norm variables to respondents who married up to four decades earlier. As discussed above, the two-part structure of each of the adat questions (‘according to traditional law’ and ‘common practice now’) increased our confidence that adat respondents reported on actual historical customs instead of observed contemporary behaviour. Additionally, we assigned adat responses to individuals based on the ethnicity of individuals rather than matching individuals to the adat expert in their current village, greatly reducing the likelihood that the adat-based values assigned to individuals merely reflect behaviour in respondents’ villages.

Examining temporal change in nuptial regimes

To investigate the role of nuptial regimes in predicting marriage behaviour over time, we undertook two sets of analyses on two different samples of ever-married adults. First, we predicted actual age at marriage as a function of the adat experts’ reports of the traditional age at marriage. Many studies of age-at-marriage employ discrete-time event history methods to mitigate concerns of censoring and non-normally distributed outcome variables and to provide coefficient estimates for time-varying independent variables (e.g., Allison 1982). Here, however, we sought to relate a continuous measure of prescribed age at marriage to a continuous measure of actual age at marriage and so employed an OLS specification. We determined that such an approach was appropriate in this case because 1) our sample was restricted to cohorts with near complete entry into marriage by the survey date, 2) age at first marriage in our sample was normally distributed (as confirmed by standard tests of normality including a ladder of power test, quantile-quantile plots, and skew tests), and 3) neither of our key independent variables, ethnic-based marriage prescriptions and the secondary schooling measure, were time-varying (see Cleves et al. 2004). We tested the sensitivity of our results to the small amount of censoring for the youngest cohort in our sample using a simulation analysis described below.

We conducted the age at marriage analyses separately for men and for women. We tested three specifications, with the adat norm for age at marriage as the main predictor variable. We first controlled for birth cohort to capture the established secular increases in marriage age. We introduced interactions between the birth cohort indicators and the adat norm for age at marriage, to test if the association of the nuptial regime with marriage behaviour had changed over time. Given previous research on the processes through which intergenerational stability in marriage behaviours weaken, we expected that the adat norms would be less important for predicting marriage behaviour of more recent cohorts, who had experienced significant changes in urbanization, industrialization, and increases in educational attainment than their predecessors.

By interacting the adat norm with birth cohort indicators, we could assess the role of adat norms over a period of considerable social change – a key component of which has been the expansion of education. In our third set of models, then, we specifically investigated whether secondary schooling moderated differences in the importance of adat law. We added both a zero-order term indicating any secondary schooling, as well as an interaction term for secondary schooling and the adat norm for age at marriage. Based on strong consensus in the literature on schooling and marriage in Southeast Asia, we expected secondary schooling to increase age at marriage, particularly for women. Under convergence theories, we would expect education, a hallmark of modernization, to attenuate the association between the prescribed age-at-marriage and actual behaviour, such that more highly-educated individuals would be less influenced by the adat norm in determining marriage timing.

Our second set of analyses predicts post-marriage residence as a function of the adat expectation for where the couple will reside after marriage. Because post-marriage residence is a couple-level behaviour, we pooled male and female respondents. The analytic sample included 7,549 respondents with complete information on ethnicity, education, and post-marriage residence. We excluded 549 (seven per cent) of the previous sample who did not report post-marriage residence. We used multinomial logistic regression to predict the categorical outcome of post-marriage residence (uxorilocal, virilocal, or neolocal). We controlled first for individuals’ birth cohort, then for birth cohort-adat norm interactions, and then for secondary schooling and a schooling-adat norm interaction. We similarly expected that time and secondary schooling might erode the association between the adat norm (for virilocality or uxorilocality) and actual post-marriage residence.

All specifications adjust for the stratified sampling scheme of the data. As a robustness check, we also estimated bootstrapped standard errors clustering at the ethnicity level; results were virtually identical to those shown below.

Results

Age at first marriage

We began by using the adat norm for age at marriage to predict actual age at marriage for Indonesian adults. Table 3 shows the results for three specifications predicting age at marriage for women. In the first column, a one-year increase in the adat norm for age at marriage for women is associated with an increase in actual age at marriage of .63 years, a significant finding. The birth cohort indicators reveal a significant rise in age at marriage for the three youngest cohorts relative to the oldest cohort. We then tested whether the association between the adat norm and actual age at marriage varied by birth cohort by including a set of interactions (column (2)). None of these interaction terms is significantly different from zero. Wald tests of the equality of the interaction terms (not shown) suggest that none of the interactions of cohort and adat norm for age at marriage are significantly different from each other. We conclude from this model that the association between ethnic-based prescriptions of marriage behaviour and actual age at marriage has not changed substantively over time. We note that the coefficient for adat norm is slightly attenuated in this specification.

Table 3.

Effect parameters for a model of the determinants of age at marriage, married Indonesian women ages 33–62, 1997 [N=4,277].

| WOMEN | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adat norm for age at marriage | 0.630 | 0.486 | 0.540 |

| [6.05]** | [1.89] | [5.56]** | |

| Birth cohort (ref = 1935–39) | |||

| 1940–44 | 0.558 | 1.851 | 0.468 |

| [1.64] | [0.37] | [1.41] | |

| 1945–49 | 0.671 | −2.59 | 0.375 |

| [1.99]* | [0.54] | [1.15] | |

| 1950–54 | 0.654 | −2.613 | 0.285 |

| [1.93] | [0.48] | [0.84] | |

| 1955–60 | 0.947 | −2.092 | 0.44 |

| [3.12]** | [0.42] | [1.46] | |

| 1960–64 | 0.821 | −2.805 | 0.224 |

| [2.84]** | [0.68] | [0.80] | |

| Some secondary school | 5.967 | ||

| [2.17]* | |||

| Interactions | |||

| Cohort * adat norm for age at marriage (ref = 1935–39) | |||

| 1940–44 | −0.079 | ||

| [0.26] | |||

| 1945–49 | 0.199 | ||

| [0.68] | |||

| 1950–54 | 0.199 | ||

| [0.61] | |||

| 1955–60 | 0.185 | ||

| [0.61] | |||

| 1960–64 | 0.221 | ||

| [0.89] | |||

| Some secondary school* adat norm for age at marriage | −0.155 | ||

| [0.95] | |||

| Constant | 7.18 | 9.53 | 8.39 |

| [4.23]** | [2.25]* | [5.29]** | |

| Observations | 4277 | 4277 | 4277 |

| R-squared | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

Source: Indonesia Family Life Survey (1993, 1997)

Absolute value of t statistics in brackets

significant at 5 per cent;

significant at 1 per cent

We then examined whether education, and not simply the passage of time proxying development, altered the relationship between adat norms and age at marriage. The zero-order term for secondary schooling reveals that women with some secondary schooling marry almost six years later than women with no secondary schooling. The adat norm for age at marriage remains significantly associated with actual age at marriage, though the coefficient attenuates somewhat from the model in column (1). The interaction term of secondary schooling and adat norm is negative but is small and not significant. The addition of the education terms in this model reduces the size and significance of the cohort terms for the two youngest cohorts. From this finding, we conclude that a large proportion of the increase in age at marriage for women over time in Indonesia is associated with increases in educational attainment, but that education has not eroded the importance of ethnic-based prescriptions for women’s marriage timing.

Table 4 presents results for the same set of models for men. In the first specification (column (1)) we find that an increase of one year in the marriage norm is associated with an increase in actual marriage age of .43 years, a weaker association than that estimated for women. In the second column we introduced the interactions of adat norm for age at marriage and birth cohort. In similar results to those for women, we find no cohort-adat norm interactions that are significantly different from zero and none that are significantly different from each other (results of Wald tests not shown).

Table 4.

Effect parameters for a model of the determinants of age at marriage, married Indonesian men ages 33–62, 1997 [N=3,821].

| MEN | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adat norm for age at marriage | 0.429 | 0.397 | 0.351 |

| [5.23]** | [1.84] | [4.28]** | |

| Birth cohort (ref = 1935–1939) | |||

| 1940–1944 | 0.781 | −2.347 | 0.762 |

| [2.00]* | [0.38] | [1.93] | |

| 1945–1949 | 0.472 | −0.864 | 0.235 |

| [1.20] | [0.15] | [0.61] | |

| 1950–1954 | 0.132 | 3.881 | −0.234 |

| [0.39] | [0.72] | [0.68] | |

| 1955–1960 | 0.437 | 0.26 | 0.079 |

| [1.37] | [0.05] | [0.25] | |

| 1960–1964 | 0.491 | −3.145 | 0.114 |

| [1.51] | [0.58] | [0.35] | |

| Some secondary school | 4.99 | ||

| [1.71] | |||

| Interactions | |||

| Cohort * adat norm for age at marriage (ref = 1935–39) | |||

| 1940–44 | 0.157 | ||

| [0.51] | |||

| 1945–49 | 0.067 | ||

| [0.23] | |||

| 1950–54 | −0.188 | ||

| [0.70] | |||

| 1955–60 | 0.009 | ||

| [0.03] | |||

| 1960–64 | 0.182 | ||

| [0.68] | |||

| Some secondary school * adat norm for age at marriage | −0.108 | ||

| [0.74] | |||

| Constant | 14.16 | 14.79 | 15.10 |

| [8.48]** | [3.41]** | [9.13]** | |

| Observations | 3,821 | 3,821 | 3,821 |

| R-squared | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

Source: Indonesia Family Life Survey (1993, 1997)

Absolute value of t statistics in brackets

significant at 5 per cent;

significant at 1 per cent

In the third specification, we assessed the role of educational attainment in conditioning the association between adat norms and behaviours. Secondary schooling is associated with a (non-significant) five-year delay in marriage relative to those without any secondary schooling. Mirroring the women’s results, the interaction of adat norm and secondary schooling is negative, small, and not significant, while the coefficient on the zero-order adat norm term remains significant. We find no evidence that secondary schooling influences the relationship between the culturally-defined marriage age and actual marriage age for men.

Post-marriage residence

We used multinomial logistic regression models to assess the association between the adat norm for post-marriage residence and actual post-marriage residence. Results for models testing this association are shown in Table 5. These regressions predicted one of three outcomes for post-marriage residence: the couple lives with the female’s parents, the couple lives with male’s parents, or the couple lives on their own or with others (non-parents). Living on their own or with others is the comparison group for the multinomial logistic models. The key predictor variable was a dichotomous indicator of being from an ethnic group with a virilocal adat norm. Male and female respondents were pooled; standard errors were adjusted for clustering at the level of the couple.

Table 5.

Effect parameters (relative risk ratios) for multinomial logistic regression models of the determinants of post-marriage residence, married Indonesian adults ages 33–62, 1997 [N=7,549].

| Postmarriage residence (base category: live on their own or with others) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

| Uxorilocal | Virilocal | Uxorilocal | Virilocal | Uxorilocal | Virilocal | |

| Adat norm: Virilocal | 0.132** | 2.538** | 0.173** | 2.550** | 0.135** | 2.798** |

| [12.55] | [9.55] | [3.69] | [3.81] | [10.60] | [9.31] | |

| Birth cohort (ref = 1935–39) | ||||||

| 1940–44 | 1.043 | 0.760* | 1.042 | 0.728* | 1.044 | 0.760* |

| [0.37] | [2.07] | [0.35] | [2.18] | [0.37] | [2.07] | |

| 1945–49 | 1.427** | 1.125 | 1.436** | 1.143 | 1.463** | 1.137 |

| [2.87] | [0.84] | [2.85] | [0.88] | [3.06] | [0.92] | |

| 1950–54 | 1.475** | 0.903 | 1.465** | 0.877 | 1.525** | 0.915 |

| [3.32] | [0.77] | [3.19] | [0.90] | [3.58] | [0.66] | |

| 1955–60 | 1.521** | 1.177 | 1.546** | 1.211 | 1.583** | 1.196 |

| [3.67] | [1.25] | [3.72] | [1.36] | [4.00] | [1.38] | |

| 1960–64 | 1.915** | 1.420** | 1.931** | 1.428* | 1.999** | 1.451** |

| [5.72] | [2.73] | [5.65] | [2.56] | [6.05] | [2.89] | |

| Some secondary school | 0.755** | 0.895 | ||||

| [3.55] | [1.18] | |||||

| Interactions | ||||||

| Cohort * adat norm: virilocal | ||||||

| 1940–44 | 0.469 | 1.425 | ||||

| [1.12] | [1.17] | |||||

| 1945–49 | 0.890 | 0.863 | ||||

| [0.20] | [0.43] | |||||

| 1950–54 | 0.924 | 1.232 | ||||

| [0.14] | [0.66] | |||||

| 1955–60 | 0.652 | 0.756 | ||||

| [0.71] | [0.90] | |||||

| 1960–64 | 0.686 | 0.929 | ||||

| [0.68] | [0.24] | |||||

| Some secondary school * adat norm: virilocal | 1.002 | 0.736 | ||||

| [0.01] | [1.52] | |||||

| Observations | 7,549 | 7,549 | 7,549 | 7,549 | 7,549 | 7,549 |

| Hausman test for independence of irrelevant alternatives (χ2, d.f., p> χ2)1 |

0.18,7, 1.00 |

2.87,7, 0.90 |

0.00,11, 1.00 |

--2 | 0.11,9, 1.00 |

2.34,9, 0.99 |

Source: Indonesia Family Life Survey (1993, 1997)

The Hausman test for independence of irrelevant alternatives is conducted on models estimated without adjustments for the IFLS sampling scheme.

χ2 < 0, indicating that the estimated model does not meet asymptotic assumptions of the Hausman test for independence of irrelevant alternatives.

The coefficients in the table can be interpreted as the degree to which each covariate changes the odds of each outcome, relative to the change in odds for the comparison group. For each model (labelled (1), (2), and (3) in Table 5), the first column displays relative risk ratios for the outcome of living with the female’s parents, and the second column displays relative risk ratios for the outcome of living with the male’s parents. In model (1), we find that an adat norm of the couple living with the male’s parents reduces the relative risk of living with the female’s parents (compared to living alone or with others) by 87 per cent (1-.132). In the same model, the same adat norm (couple lives with male’s parents) increases the relative risk of living with the male’s parents (compared to living alone or with others) by two and a half times. Membership in a younger cohort substantially increases the risk of living with the female’s parents relative to living alone or with others.

The second specification tested whether the association of the adat norm for post-marriage residence with actual post-marriage residence has changed over time. We find no significant interactions using Wald tests to examine between-coefficient differences. The association between adat norm and behaviour remains sizeable and significant in this model, and the finding that younger cohorts are at increased risk of living with the female’s parents holds.

In model (3) we added secondary schooling and the interaction of secondary schooling with the adat norm to model (1). We observe that secondary schooling does not significantly alter the relationship between adat predictions of post-marriage residence and actual residence with either set of parents, relative to living alone. Unlike the age at marriage specifications discussed above, the addition of the secondary schooling covariate does not substantively change the cohort estimates.

Robustness checks

Several additional analyses were undertaken to test the robustness of our results to alternative specifications or assumptions. Our method of assigning adat norms to individuals ignored the potentially substantial regional variation in ethnic norms across Indonesia, and in urban vs. rural areas. We thus repeated our analyses with a finer matching of adat norms by merging adat norms to respondents based on the ethnicity of the respondent as well as on the province and urbanicity of the respondent’s reported residence at age 12. This allowed for a more localized measure of exposure to adat norms during adolescence. Results from these analyses were directionally equivalent to the results shown in Table 3 and Table 4, with coefficients on the term for the adat norm reduced by about one-third for women and by about one-half for men. Results for post-marriage were nearly identical to those presented in Table 5.

To address the concern that adat experts may merely have reported observed behaviour instead of traditional norms, we re-estimated the age at marriage analyses using the adat expert’s responses for ‘common practice now’ rather than ‘traditional practice.’ For both men and women, the coefficients on the adat norm are reduced by one-third to two-thirds, suggesting weaker association with actual age at marriage. However, the interaction term between the ‘common practice now’ report from the adat expert and the youngest birth cohort in Model 3 doubles in size, consistent with the common practice measure capturing the most recent marriage behaviour observed by adat experts.

Another valid concern with our analytic approach is that we have biased the sample by including only already-married respondents. In the youngest cohort in particular, those born 1960–1964, it is possible that those unmarried by 1997 differed in their relationship between adat norm for age at marriage and actual age from those already married. We tested the sensitivity of our results with a simulation that assigned marriage ages to the 48 unmarried women and 45 unmarried men in this cohort. Marriage ages were generated from the upper tail of the sex-specific age distribution of marriage ages in the previous cohorts, but assigned to unmarried respondents in the reverse order from that predicted by each unmarried respondent’s adat norm. In this way, we assumed that the unmarried members of the 1960–1964 cohort would go on to marry at ages least predicted by their adat norm. We then reestimated models 1–3 from Table 3 (for women) and Table 4 (for men). Results (not shown) were substantively identical to the models presented. We conclude that censorship is small enough in our sample that our decision to limit the analysis to already-married respondents is highly unlikely to introduce bias into our results.

Discussion

Our study assessed the influence of ethnic-specific cultural norms on observed marriage behaviour in a diverse population during a period of rapid economic development. Along two dimensions of marriage behaviour, age at marriage and post-marriage residence, we demonstrate that adat norms are strong predictors of actual behaviour. The ethnic-specific traditional age at marriage identified by adat experts predicts the actual age at marriage for both men and women born between 1935 and 1964. Similarly, an adat norm for living with the male’s parents is strongly and inversely related to actual coresidence with the female’s parents, and comparably positively related to coresidence with the male’s parents. It is particularly striking that these associations hold after controlling for educational attainment, and do not appear to have changed over time.

We conclude that nuptial regimes and the importance of cultural norms in Indonesia have persisted in the face of economic development. We broadly measured economic development in two ways here: by the passage of time, and by increases in educational attainment. Despite dramatic changes in economic opportunities, rural-urban migration, and other modernization forces that might be expected to have interrupted the intergenerational transmission and the importance of these adat norms, ethnic-based distinctions in marriage behaviours are still highly salient.

Our results suggest, then, a reinterpretation of convergence theory to a model in which modernization and persistent cultural identities coexist. We find in Indonesia that education is associated with delays in marriage, both across and within cohorts, but that the variation in marriage timing between ethnic groups a) stays the same across population gains in education over time and across education variation with cohorts and b) is explicitly linked to cultural prescriptions of appropriate marriage behaviour as proposed by cultural leaders. Indeed, it may be that marriage delays and other changes in nuptial regimes can occur only while ethnic-based cultural identities remain distinct. As Abbasi-Shavazi (2008) writes about modernization and nuptiality, change in family organization ‘occurs so long as it does not pose a major threat to cultural identity’ (p.4).

It is important to address two alternative explanations for our findings. Our use of adat norms reported in 1997 as predictors of marriage behaviour occurring much earlier may raise concerns that adat experts were merely reporting observed concurrent behaviours in their communities. Our compelling finding that the relationship between adat norms and marriage behaviours holds over time lessens the potential confounding nature of this issue: if we had found that adat responses were only related to current behaviour, and not past marriage behaviour, it might signal that adat responses merely represented the current behaviour observed by the adat experts. While we find no evidence of this, we acknowledge that using aggregated adat expert responses as a source of cultural norms may be a limitation to the study.

Another possible explanation for our findings on post-marriage residence is the coincidental alignment of adat norms with modern social and economic realities. For example, if establishing an independent household has become more expensive in recent decades, then intergenerational co-residence after marriage may be more an arrangement of convenience or necessity than a reflection of adherence to traditional nuptial norms (Hirschman and Nguyen 2002). However, the persistent strong association of patrilocal and matrilocal norms with post-marriage residence questions the notion that financial necessity is the sole driver of intergenerational co-residence among younger cohorts. Of course, some of the functions of intergenerational co-residence (e.g. child care, asset sharing) can still be accomplished if the couple lives near, but not in the same household as, their parents. We did not examine that type of intergenerational co-residence here.

In addition, our study did not consider other potentially important moderators including parental education, occupation, and landholding; these may be strong determinants of the utility of traditional family systems and therefore of the importance of nuptial regimes in predicting marriage behaviour of the next generation. For example, Yabiku (2006) finds evidence that the proportion of neighbourhood land devoted to agriculture is positively associated with marriage hazard in Nepal.

Several studies have examined the persistently low age at marriage in Indonesia, even despite rapid increases in educational attainment and the relative economic independence of Indonesian women (Jones 2001, 2004; Savitridina 1998). Our findings may offer some insight here. Across the three decades we examined, the adat norms for the age at marriage continue to exert a strong force on actual age at marriage for both men and women, unattenuated by educational attainment. Even more remarkably, the interaction of secondary schooling attainment and adat norm has no significant effect on age at marriage, suggesting that further increases in educational attainment may not attenuate ethnic distinctions in marriage patterns in the future. It is possible that adherence to cultural norms surrounding marriage behaviour is in part responsible for the sustained early marriage patterns exhibited in Indonesia relative to other Asian contexts.

Looking forward, we argue that our results are relevant for two notable trends in Indonesia: the changing size and structure of the Indonesian family, and the recent revival of adat and adat-based political activism. Particularly in urban areas, it is clear that family structures are undergoing significant change, with increasing proportions of women delaying marriage past age 30. Jones (2005, 2007) argues that these delays have multiple determinants, including uncertainty about the country’s economic future, increasing numbers of partners with conflicting religious backgrounds, and women’s changing values about the appeal of or benefits to marriage. In the coming decades, scholars anticipate even later marriages, smaller families, and more never-married adults (Grace 2004; Hull 2003). These changes will have long-term implications for the organization of the family, for women’s productive and reproductive roles, and particularly for old-age support. Our results suggest that these rapid changes may be attenuated somewhat by the adherence of Indonesians to traditional expectations about marriage behaviour.

Finally, we close by mentioning the revival and resurgence of adat in Indonesia in the past decade (i.e., after the marriages in this study took place). After President Suharto’s resignation in 1998, groups representing different ‘adat communities’ elected representatives to parliament (Bowen 2003). In 1999, two regional autonomy laws were passed granting more importance to adat authority in local decision-making and administration (Davidson and Henley 2007). From decisions about tourism development in Bali to the resurgence of ancient sultanates in Sumatra, adat authority is being cited as a legitimate source of power, order, and identity (Bowen 2003; Davidson and Henley 2007).

Scholars of adat revivalism speculate that the trend may also reflect a reactionary response to the modernization and socioeconomic change associated with the New Order. If the New Order had stressed the unification of Indonesia through tight central control at the expense of local customs and institutions, then its downfall has opened the door to a resurgence of regional autonomy and local emphasis represented by adat systems (Bowen 2003; Davidson and Henley 2007). We speculate that family processes and marriage behaviour may respond to this adat revival as well. Our results suggest that marriage timing and household formation processes remained linked with adat norms throughout the New Order. Young people coming of age in the post-New Order Indonesia may be even more motivated to look to adat in setting expectations about the transition to adulthood. If so, we can anticipate a continued diversity of nuptial regimes within Indonesia and a continued low age at marriage for women relative to Indonesia’s Southeast Asian neighbors.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation, the National Institute for Child and Human Development, and the California Center for Population Research. The authors would like to thank Elizabeth Frankenberg for her generous help with this research, as well as Jennifer Glick, Jim Raymo, Scott Yabiku, participants in seminars at UCLA and the Population Association of America meetings, and two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments.

Contributor Information

Alison M. Buttenheim, University of Pennsylvania

Jenna Nobles, University of Madison, Wisconsin.

References

- Abbasi-Shavazi, Jalal Mohammad, McDonald Peter, Hosseini-Chavoshi Meimanat. Modernization or cultural maintenance: The practice of consanguineous marriage in Iran. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2008;40:911–933. doi: 10.1017/S0021932008002782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah Taufik. Adat and Islam: An examination of conflict in Minangkabau. Indonesia. 1966;2:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Allison Paul D. Discrete-time methods for the analysis of event histories. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:61–98. [Google Scholar]

- Billari Francesco C, Liefbroer Aart C. Should I stay or should I go? The impact of age norms on leaving home. Demography. 2007;44(1):181–198. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billy John OG, Brewster Karin L, Grady William R. Contextual effects on the sexual behavior of adolescent women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56(2):387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn Susan, Bessell Sharon. Marriageable age: political debates on early marriage in twentieth-century Indonesia. Indonesia. 1997;63:107–141. [Google Scholar]

- Boomgaard Peter. Bridewealth and birth control: Low fertility in the Indonesia archipelago, 1500–1900. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(2):197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen John R. Shari'a, State and Social Norms in France and Indonesia. Leiden: Leiden ISIM; 2001. Working Paper Series #3. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen John R. Islam, Law, and Equality in Indonesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Butler Amy C. Welfare, premarital childbearing, and the role of normative climate: 1968–1994. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(2):295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Cain Mead T. The household life cycle and economic mobility in rural Bangladesh. Population and Development Review. 1978;4(3):421–438. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John C, Reddy PH, Caldwell Pat. The causes of marriage change in south India. Population Studies. 1983;27:343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Cammack Mark, Young Lawrence, Heaton Tim B. Legislating social change in an Islamic society--Indonesia's marriage law. American Journal of Comparative Law. 1996;44(1):45–73. [Google Scholar]

- CBS Indonesia. Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2002–03. Macro International Inc. (MI); 2003. Calverton, Maryland: Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) [Indonesia], State Ministry of Population/National Family Planning Coordinating Board (NFPCB), Ministry of Health (MOH) [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew, Chamratrithirong Apichat. Variations in marriage patterns in central Thailand. Demography. 1988;25(3):337–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleves Mario A, Gould William, Gutierrez Roberto. An Introduction to Survival Analysis Using Stata. College Station, Texas: Stata Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson Jamie S, Henley David. Introduction: Radical conservatism --the protean politics of adat. In: Davidson Jamie S, Henley David., editors. The Revival of Tradition in Indonesian Politics: The Deployment of Adat from Colonialism to Indigenism. Oxon: Routledge; 2007. pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Deolalikar Anil B. Gender differences in the returns to schooling and in school enrollment rates in Indonesia. The Journal of Human Resources. 1993;28(4):899–932. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg Elizabeth, Chan Angelique, Ofstedal Mary Beth. Stability and change in living arrangements in Indonesia, Singapore, and Taiwan, 1993–1999. Population Studies. 2002;56:201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg Elizabeth, Karoly Lynn. The 1993 Indonesian Family Life Survey: Overview and Field Report. Santa Monica: RAND; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg Elizabeth, Lillard Lee A, Willis Robert J. Patterns of intergenerational transfers in southeast Asia. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(3):627–641. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg Elizabeth, Thomas Duncan. The Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS): Study Design and Results from Waves 1 and 2. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell Elizabeth, Palloni Alberto. Persistent marriage regimes in changing times. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2004;66:1201–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler Paul J, Molyneaux John W. How economic development and family planning programs combined to reduce Indonesian fertility. Demography. 1994;31(1):33–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire Dirgha J, Axinn William G, Yabiku Scott T, Thornton Arland. Social change, premarital nonfamily experience, and spouse choice in an arranged marriage society. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;111(4):1181–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Goode William J. World Revolution and Family Patterns. New York: The Free Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Grace Jocelyn. Sasak women negotiating marriage, polygyny, and divorce in rural East Lombok. Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context. 2004;10 Retrieved from http://wwwsshe.murdoch.edu.au/intersections/issue10/grace.html. [Google Scholar]

- Hajnal John. Two kinds of preindustrial household formation systems. Population and Development Review. 1982;8(3):449–494. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton Tim B. Socioeconomic and familial status of women associated with age at first marriage in three Islamic societies. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1996;27:41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman Charles, Nguyen Huu Minh. Tradition and change in Vietnamese family structure in the Red River delta. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:1063–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman Charles, Teerawichitchainan Bussarawan. Cultural and socioeconomic influences on divorce during modernization: Southeast Asia, 1940s to 1960s. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(2):215–253. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker MB. Adat Law in Modern Indonesia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo Graeme J, Hull Terence H, Hull Valerie J, Jones Gavin W. The Demographic Dimension in Indonesian Development. Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hull Terence. Demographic perspectives on the future of the Indonesian family. Journal of Population Research. 2003;20(1):51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Idrus Nurul Ilmi. Behind the notion of siala: Marriage, adat and Islam among the Bugis in South Sulawesi. Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context. 2004;10 Retrieved from http://wwwsshe.murdoch.edu.au/intersections/issue10_contents.html. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Gavin W. Marriage and Divorce in Islamic South-East Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Gavin W. Which Indonesian women marry youngest, and why? Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 2001;32(1):67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Gavin W. Not "when to marry" but "whether to marry": The changing context of marriage decisions in East and Southeast Asia. In: Jones G, Ramdas Kamalini, editors. (Un)tying the Knot: Ideal and Reality in Asian Marriage. Singapore: Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore; 2004. pp. 3–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Gavin W. The "flight from marriage" in South-East and East Asia. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2005;36(1):93–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Gavin W. Delayed marriage and very low fertility in Pacific Asia. Population and Development Review. 2007;33(3):453–478. [Google Scholar]

- Kato Tsuyoshi. Different fields, similar locusts: Adat communities and the Village Law of 1979 in Indonesia. Indonesia. 1989;47:89–114. [Google Scholar]

- LeBar Frank M. Ethnic Groups of Insular South-East Asia. New Haven: Human Relations Area File Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Levine David I, Kevane Michael. Are investments in daughters lower when daughters move away? Evidence from Indonesia. World Development. 2003;31(6):1065–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra Anju. Gender and the timing of marriage: Rural-urban differences in Java. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59(2):434–450. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra Anju, Tsui Amy Ong. Marriage timing in Sri Lanka: The role of modern norms and ideas. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58(2):476–490. [Google Scholar]

- Marini Margaret Mooney. Age and Sequencing Norms in the Transition to Adulthood. Social Forces. 1984;63(1):229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Mensch Barbara, Singh Susheela, Casterline John B. Trends in the timing of first marriage among men and women in the developing world. In: Lloyd Cynthia B, Behrman Jere R, Stromquist Nelly P, Cohen Barney., editors. The Changing Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries: Selected Studies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel Edward A, Gertler Paul, Levine David I. Does social capital promote industrialization? Evidence from a rapid industrializer. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2005;87(4):754–762. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel Edward A, Gertler Paul, Levine David I. Does industrialization build or destroy social networks? Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2006;54(2):287–317. [Google Scholar]

- Millar Susan Bolyard. Bugis Weddings: Rituals of Social Location in Modern Indonesia. University of California at Berkeley; 1989. Center for South and Southeast Asia Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Pramualratana Anthony, Havanon Napaporn, Knodel John. Exploring the normative basis for age at marriage in Thailand: An example from focus group research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1985;47(1):203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Savitridina Rini. Determinants and consequences of early marriage in Java, Indonesia. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 1998;12(2):25–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillander Kenneth. Acting Authoritatively: How Authority in Expressed Through Social Action Among the Bentian of Indonesian Borneo. Helsinki: University of Helsinki; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Singh Susheela, Samara Renee. Early marriage among women in developing countries. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;22(4):148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Spyer Patricia. Diversity with a difference: Adat and the New Order in Aru (Eastern Indonesia) Cultural Anthropology. 1996;11(1):25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss John, Beegle Kathleen, Sikoki Bondan, Dwiyanto A, Herawati Y, Witoelar F. The Third Wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS3): Overview and Field Report. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sulistyawati Endah, Noble Ian R, Roderick Michael L. A simulation model to study land use strategies in swidden agriculture systems. Agricultural Systems. 2005;85(3):271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Jean G. Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Teitler Julien O, Weiss Christopher C. Effects of neighborhood and school environments on transitions to first sexual intercourse. Sociology of Education. 2000;73(2):112–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Haar Barend. In: Adat Law in Indonesia. Hoebel E Adamson, Schiller A Arthur., editors. New York: New York International Secretariat, Institute of Pacific Relations; 1948. Translated from the Dutch; Edited with an iIntroduction by. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Duncan, Frankenberg Elizabeth, Smith James P. Lost but not forgotten: Attrition and follow-up in the Indonesia Family Life Survey. The Journal of Human Resources. 2001;36(3):556–592. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland, Fricke Thomas E. Social change and the family: comparative perspectives from the West, China and South Asia. Sociological Forum. 1987;2(4):746–779. [Google Scholar]

- Ting Kwok-fai, Chiu Stephen WK. Leaving the parental home: Chinese culture in an urban context. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(3):614–626. [Google Scholar]

- Yabiku Scott T. The effect of non-family experiences on age of marriage in a setting of rapid social change. Population Studies. 2005;59(3):339–354. doi: 10.1080/00324720500223393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabiku Scott T. Land use and marriage timing in Nepal. Population and Environment. 2006;27:445–461. [Google Scholar]