Abstract

The ovarian cystic teratoma is a rare cause of autoimmune haemolytic anaemia by warm antibodies, resistant to corticotherapy, with few case reports published in the medical literature.

We present a case of a 45-year-old woman admitted to hospital due to general weakness. Laboratory studies revealed macrocytic anaemia, biochemical parameters of haemolysis and peripheral spherocytosis. The direct Coombs test was positive. Viral serologies, anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies and β2-microglobulin were negative. CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis showed a heterogeneous right anexial lesion. The patient was treated with corticotherapy without improvement of anaemia. Regression of extra-vascular haemolysis and normalisation of haemoglobin was obtained only after laparoscopic splenectomy and right ooforectomy, and the histopathology of the right anexial mass revealed a cystic teratoma.

Previously published cases controlled the haemolysis by surgically removing the lesion associated with splenectomy.

Background

Immune haemolytic anaemia (IHA) is defined as an erythrocyte destruction by the combined action of complement factors and the reticuloendothelial system triggered by antibody bonding of erythrocyte antigens. The autoimmune form is a heterogeneous disease group characterised by endogenous production of antibodies against self-erythrocyte antigens. There is an estimated incidence of 1–3 cases per 100 per year1 and the causes include warm antibody autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA), cryoaglutinin syndrome, cold paroxystic haemoglobinuria and drug-induced AIHA. AIHA can be further classified as idiopathic or secondary with lymphoproliferative disease, autoimmune disorders and infectious diseases1,2 being the most common causes (table 1). Although rare, AIHA can be an early paraneoplasic phenomenon of non-lymphoid neoplasm-like dermoid cysts and ovarian teratoma, Kaposi sarcoma and carcinoid. Few cases of AIHA associated with ovarian neoplasm have been described, almost always associated to dermoid cysts, and treatment involves the surgical removal of the lesion.3–7 We report a case of AIHA associated with an ovarian teratoma with haemolytic regression after ooforectomy plus splenectomy.

Table 1.

Classification of autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

| Warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia |

| Idiopathic |

| Secondary (lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune disorders) |

| Cold autoimmune haemolytic anaemia |

| Cold agglutinin syndrome |

| Idiopathic |

| Secondary |

| Acute transient (infections) |

| Chronic (lymphoproliferative disorders) |

| Paroxysmal cold haemoglobinuria |

| Idiopathic |

| Secondary |

| Acute transient (infections other than syphilis) |

| Chronic (syphilis) |

| Mixed-type autoimmune haemolytic anaemia |

| Idiopathic |

| Secondary (lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune disorders) |

| Drug-induced immune haemolytic anaemia |

| Autoimmune type |

| Drug absorption type |

| Neo-antigen type |

Adapted from1.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old female patient attended our hospital because of shortness of breath, general weakness, fatigue and jaundice. The patient had been well until 3 weeks earlier when symptoms developed. She had a history of alcohol consumption of about 30 g/day and had no history of prior medication or recent drug exposure. Examination revealed only a discrete sclera icterus, pale skin and palpable hepatic tip (3 cm below right inferior costal border).

Investigations

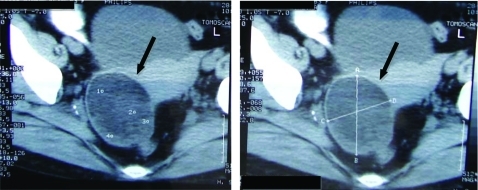

Laboratory tests were performed (table 2) revealing severe macrocytic anaemia (haemoglobin 7.6 g/dl; mean corpuscular volume 129 fl) with associated haemolysis (aspartato aminotransferase 100 U/litre, total bilirubin 277 mg/dl, lactate dehydrogenase 1299 U/litre and haptoglobin <781 mg/dl) and spherocytosis with reticulocytosis in the peripheral blood smear. The direct and indirect antiglobulin Coombs test was positive (panreactive with positive IgG and negative C3) and the diagnosis of warm AIHA was made. The further complementary analytic study for AIHA cause was inconclusive with negative virus serology (B and C hepatitis, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus), as well as anti-nuclear antibodies and anti-double-stranded DNA. Serum protein electrophoresis was also normal as well as the β2-microglobulin levels. An abdominal CT scan obtained after oral and intravenous administration of contrast material revealed a right anexial lesion (80 mm greater diameter), cystic and heterogeneous in content, compatible with a cystic teratoma (figure 1).

Table 2.

Haematological and biochemical results at hospital admission

| Haematological parameter | Result |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 7.6 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fl) | 129 |

| Reticulocitary index | 11.8 |

| Platelet count (per mm3) | 183000 |

| White cell count (per mm3) | 11000 |

| Blood smear findings | Anisocytosis ++ |

| Spherocytosis ++ | |

| Biochemical parameter | Result |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/litre) | 100 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 2.77 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/litre) | 1399 |

| Haptoglobin (mg/dl)* | <7.81 |

| Urea nitrogen | Normal range |

| Creatinine | Normal range |

| Albumin | Normal range |

| B12 vitamin | Normal range |

| Folic acid | Normal range |

*Normal range is 16–199 mg per decilitre

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT scan (after oral and intravenous administration of contrast material) revealed a right anexial lesion (black arrows) with 80 mm on greater diameter, cystic and heterogeneous content, compatible with an ovarian cystic teratoma.

Treatment

After the fifth day of admission, corticotherapy was prescribed (1 g of methylprednisolone pulses for 3 days followed by prednisone 1.5 mg/kg/day) as well as folic acid (2 mg/day) with persistence of anaemia and biochemical haemolysis (table 3.). After 15 days of corticotherapy, a 3-day trial of endovenous immunoglobulin (IG ev) treatment was further prescribed due to maintenance of severe anaemia, but extra-vascular haemolysis still persisted although later with stable haemoglobin values.

Table 3.

Laboratory test results after hospital admission

| D1 | D5 | D7 | D8 | D10 | D15 | |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 7.6 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 7.9 |

| Reticulocitary index | 9.7 | 9.3 | 10.4 | 13.2 | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/litre) | 100 | 118 | 100 | 83 | ||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 2.77 | 3.39 | 2.77 | 2.58 | 2.71 | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/litre) | 1399 | 1485 | 1636 | 1456 | 1791 |

D1–15, days of hospital admission.

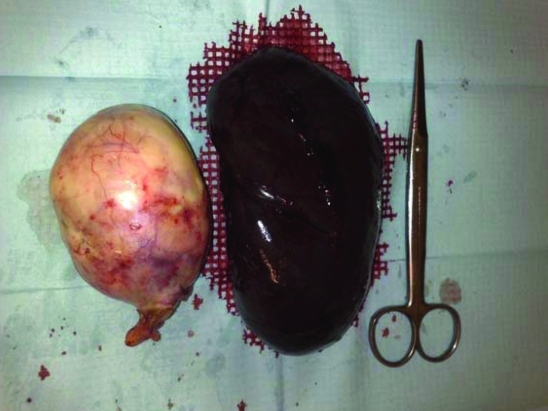

Under corticotherapy, the patient was submitted to right ooforectomy with splenectomy (figure 2).The anexial tumour was 140×90×110 mm and histopathology examination confirmed the ovarian cystic teratoma diagnosis (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Macroscopic aspect of the right anexial lesion and spleen after surgical removal. The ovary is transformed into a uniloci cystic formation with 140×90×80 mm, fine wall, pink and smooth external surface and tarnished internal surface with pasty yellow material with hair adherent. Spleen with complete capsule and marked parenchyma congestion.

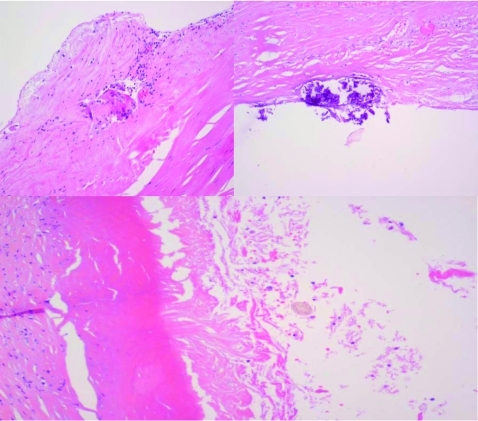

Figure 3.

Ovary fibre connective wall with extensive and marked hyalinisation with rare sections of hairs (arrow) observed. Because of the morphologic aspects observed in the macroscopic and histological cuts, we conclude it to be a mature cystic teratoma.

Outcome and follow-up

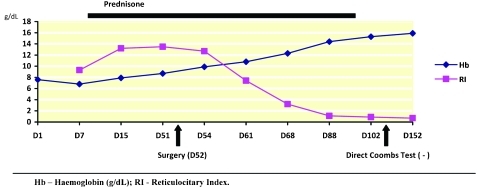

A few days after the procedure, there was a progressive regression of biochemical haemolysis with stable haemoglobin and the prednisone dose was withdrawn slowly.

Over the next few months after hospital discharge, haemoglobin raised to normal values (figure 4) and the biochemical parameter of haemolysis decreased, although the direct Coombs test was positive until the third month after surgery when corticotherapy was finally stopped. AIHA by warm antibodies associated with an ovarian cystic teratoma was the final diagnosis.

Figure 4.

Haematological evaluation before and after surgical intervention. Because of persistent anaemia and haemolysis parameter, the patient started prednisone (1.5 mg/kg/day) after 3 days of methylprednisolone pulses. Surgery was performed on day 52 day after hospital admission. Haematological and biochemical evaluation progressively normalised after surgery and remained in regression after prednisone was withdrawn. Direct Coombs test was negative from the third month after surgery.

Discussion

Although the association of AIHA and ovarian teratoma has been made since 1938, by West-Watson and Young,8 it is still a rare paraneoplasic phenomenon in ovarian tumour patients with only 26 cases reported until 2003.9 The ovarian teratoma is relatively common, but the incidence of haemolytic anaemia in patients with this tumour is, obviously, low and at present we do not know why a very occasional tumour produces this reaction when the vast majority do not.

Payne et al10 in 1981 analysed 19 case reports previously published of patients with haemolytic anaemia associated with ovarian tumours. Sixteen patients had a successful response with tumour removal alone, one patient had a total response after ooforectomy and splenectomy were performed simultaneously and two patients died before surgery by non-related causes. Only three patients had a partial response to corticotherapy, which was considered negligible, and then went on to have the tumour removed which consequently cured the disorder. Disappearance of autoantibody following tumor removal was documented in many instances with time intervals of 2 weeks to 7 months following surgery.

The haemolysis mechanism has not yet been clarified and further research would be of interest as available data has mainly reported on the past.4–7,9–11 The mechanisms proposed are: (1) liberation of the substance by the tumour, which alters the red cell surface rendering it antigenic to the host; (2) the tumour or its contents may contain material antigenic to the host, stimulating the production of antibodies that cross-reacts with host erythrocytes; (3) the ovarian tumour itself produces red cell antibody providing it is immunologically competent. Most of the cases tend to support this last hypothesis, because antibody production seems to cease immediately after tumour removal in almost all cases reported, and antibody serum disappearance seems to matches well with the half-life of serum IgG.

In our case report, the extra-vascular haemolysis was refractory to corticotherapy and, due to the clinical instability and the increasing biochemical haemolysis, treatment with splenectomy was performed associated with laparoscopic ooforectomy allowing a further histopathology characterisation of the ovarian lesion. Since both interventions were performed at the same time and complete haemolysis regression was obtained, it seems reasonable to think, from similar case reports and review of the literature, that tumour removal was the major factor in resolving the disorder. Furthermore, the persistence of auto-antibodies up to 3 months after the surgical procedure is also reported in the literature and can be detected up to 10 months after surgery.

Conclusion

The early evaluation of anexial mass in young patients with corticotherapy-resistant AIHA is important as new cases of ovarian teratoma and haemolysis association are described. Although the haemolysis mechanism has not been yet clarified, the production of red cell antibodies by the tumour is the main hypothesis considered due to the fact that antibody production seems to cease immediately after tumour removal. The correct treatment is surgical removal of the ovarian lesion alone, avoiding the useless and non-treatable removal of the spleen and the life-long treatment of a splenectomy. The importance of recognising this association, despite its variety and the few cases published, is the excellent prognosis in such cases following ooforectomy.

Learning points

Ovarian cystic teratoma is a rare cause of autoimmune haemolytic anaemia by warm antibodies, resistant to corticotherapy, with few case reports published in medical literature.

Of the previously published cases, control of the haemolysis was obtained after surgical removal of the lesion associated with splenectomy; however, recent cases report of the therapeutic success of removing the tumour.

The early anexial mass evaluation in young patients with corticotherapy-resistant AIHA assumes greater importance as new cases of ovarian teratoma and haemolysis association are being described. Although haemolysis mechanism has not been yet clarified, the production of red cell antibodies by the tumour is the main hypothesis considered due to the fact that antibody production seems to cease immediately after tumour removal. The proper treatment is surgical removal of the ovarian lesion alone, sparing the useless removal of the spleen and the life-long treatment regarding splenectomy. The importance of recognising this association, despite its variety and the few cases published, is the excellent prognosis in such cases following ooforectomy.

We think, due to the few cases published, this case report will be helpful to the medical community.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gehrs BC, Friedberg R. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Am J Hem 2002; 69: 258–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valent P, Lechner K. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune haemolytic anemia in adults: a clinical review. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2008; 120: 136–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glorieux I, Chabbert V, Rubie H, et al. Autoimmune haemolytic anemia associated with a mature ovarian teratoma. Arch Pediatr 1998; 5: 41–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobo F, Pereira A, Nomdedeu B, et al. Ovarian dermoid cyst associated autoimmune haemolytic anemia: a case report with emphasis on pathogenic mechanisms. Am J Clin Pathol 1996; 105: 567–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buonanno G, Gonnella F, Pettinato G, et al. Autoimmune haemolytic anemia and dermoid cyst of the mesentery. A case report. Cancer 1985; 54: 2533–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young RH. New and unusual aspects of ovarian germ cells tumours. Am J Surg Pathol 1993; 17: 1210–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim I, Lee JY, Kwon JH, et al. A case of autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with an ovarian teratoma. J Korean Med Sci 2006; 21: 365–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West-Watson WN, Young CJ. Failed splenectomy in acholuric jaudice and the relation of toxaemia to the hemolytic crisis. Br Med J 1938; 1: 1305–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarnal V, Sachdev A, Singh R, et al. Autoimmune haemolytic anemia associated with benign ovarian cyst: a case report and review literature. Indian J Med Sci 2003; 57: 504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Payne D, et al. Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia associated with ovarian dermoid cyst: case report and review of the literature. Cancer 1981; 43: 721–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker L, Brain MC, et al. Autoimmune haemolytic anemia associated with ovarian dermoid cyst. J Clin Path 1968; 21: 628–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]