Abstract

Objectives

The authors conducted a study to describe the general dentists, practices, patients and patient care patterns of the dental practice-based research network (PBRN) Northwest Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry (PRECEDENT).

Methods

Northwest PRECEDENT is a dental PBRN of general and pediatric dentists and orthodontists from five U.S. states in the Northwest: Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Utah and Washington. The authors collected data from general dentists in Northwest PRECEDENT (n = 101) regarding the diagnosis and treatment of oral diseases in a survey with a systematic random sample of patients (N = 1,943) visiting their practices. They also obtained demographic data from the general dentists and their patients.

Results

The authors found that 50 percent of the general dentists were 51 to 60 years of age, 14 percent were female and 76 percent were non-Hispanic white. More than one-half (55 percent) of the dentists had practiced dentistry for more than 20 years, 83 percent had private solo practices and 32 percent practiced in rural community settings. The majority (71 percent) of patients visiting the dental practices was in the age range of 18 to 64 years, 55 percent were female and 84 percent were non-Hispanic white. In terms of reasons for seeking dental care, 52 percent of patients overall visited the dentist for oral examinations, checkups, prophylaxis or caries-preventive treatment. In the preceding year, 85 percent of the patients had received prophylaxis, 49 percent restorative treatments, 34 percent caries-preventive treatments and 10 percent endodontic treatments.

Conclusions

Northwest PRECEDENT general dentists are dispersed geographically and are racially and ethnically diverse, owing in part to efforts by network administrators and coordinators to enroll minority dentists and those who practice in rural areas. Estimates of characteristics of dentists and patients in Northwest PRECEDENT will be valuable in planning future studies of oral diseases and treatments.

Keywords: Dental private practice, dentists, office visits, research

Recent emphasis at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Md., on translation of research into practice identified research networks as a major tool in NIH’s “roadmap” for re-engineering the clinical research enterprise.1 This prompted the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), Bethesda, to fund three general dental practice-based research networks (PBRNs).2–4 If we apply the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s definition of primary care PBRNs5 to the dental field, a general dental PBRN can be defined as a group of general dental practices devoted principally to the primary dental care of patients and affiliated in their mission to investigate questions related to dental practice and to improve the quality of primary dental care. In the PBRNs, practicing dentists work collaboratively with academic investigators to develop research questions and research protocols, conduct studies and translate new knowledge into practice. Academic investigators provide the research methodology and the network’s organizational structure for the development and conduct of the studies. The objectives of the network are to create the structure and process needed for studying the effectiveness of the routine care in general dental practice settings; to provide investigative experience for dental practitioners as they contribute to the evidence base for dental practice; and to disseminate study results and help accelerate the translation of research into practice.

The Northwest Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry (PRECEDENT) is one of the three general dental PBRNs funded by NIDCR in 2005. It includes general dentists, pediatric dentists and orthodontists from five U.S. states in the Northwest: Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Utah and Washington. The schools of dentistry at the University of Washington (UW), Seattle, and the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland, organize and administer the network activities. As new PBRNs develop, they seek opportunities to create a sense of identity and to engage the network members in the research activities.

For a network’s first study, it is important that investigators take the following steps to ensure the success of the project and to maintain a balance between methodological rigor and ease of conduct:

identify a practical and relevant study topic;

develop a simple protocol for conduct of the study;

involve network members in the initial phases of the study development.

A first study designed to gather information regarding network dental practices, their dentists, their patients and patient visits can meet these criteria and provide valuable information for future research projects and for comparisons with other populations. Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention6 (CDC), Atlanta, in its National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, has reported about the prevalence of oral diseases in the general population, little is known about the prevalence of oral diseases among patients in the United States who visit their dentists. Our aim in this study was to describe the dentists, practices, patients and patient care patterns of Northwest PRECEDENT. We obtained our data from PRECEDENT Study 001, a study that all general dentist members were required to complete on joining the network and that consisted of an evaluation of the oral health conditions of a random sample of 20 patients in each network practice. Although Northwest PRECEDENT now also includes pediatric dentists and a network of orthodontists, our study was limited to general dentists and their practices.

METHODS

Study design and selection of practices and patients

Study design and settings

We conducted a cross-sectional study of the oral health conditions of the patients and the treatments performed by general dentists in their dental practices from September 2006 through July 2009 in Northwest PRECEDENT, a dental PBRN. When we terminated the study, 93 dentists had enrolled 20 patients, two had enrolled 19 patients and six had enrolled from five to 12 patients during an average of 2.5 months (standard deviation = 2.9) per practice, for a total of 1,943 participants from 101 practices. One dentist quit the network before completing the study. We enrolled dentists in the study in a sequential manner, so the last seven had not reached their goal of 20 patients when enrollment ended.

Practice recruitment

Northwest PRECEDENT chair investigators invited dentists to join the network by means of oral presentations they gave at national and regional conferences and study club meetings. Press releases and articles about Northwest PRECEDENT were published in academic, professional and news journals, and network chair staff members sent letters of invitation to licensed dentists in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Utah and Washington. Interested dentists filled out an online registration at the Northwest PRECEDENT Web site (“www.nwprecedent.net”).

Practice selection

To be eligible to participate in the studies of Northwest PRECEDENT, general dentists were required to take part in a five-hour continuing dental education course regarding the principles of good clinical research7 and instruction in responsible conduct of research in humans and regarding relevant Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations for research. Regional coordinators invited practicing general dentists who completed the training to participate in the study.

Training and research conduct

Study materials—including questionnaires, consent and HIPAA forms, manual of operations and study informational flyers—were mailed to the dental offices by staff of the data coordinating center. The dentist and dental practice staff reviewed the materials and participated in telephone training sessions given by research coordinators regarding the study-specific methods and the electronic Web-based data entry system.

Patient selection

We selected participants by using a systematic random sample of dental visits in which each dental office was assigned a starting date and a sampling interval. We adjusted the sampling interval for each practice on the basis of patient volume, so that each practitioner invited at least one and no more than two participants per day. Dentists invited every nth patient visiting the office in the study period to participate until 20 participants within each practice were enrolled in the study. Dentists or dental team members explained the purpose and procedures of the study to the patients and obtained informed consent. Patients were not eligible to participate in the study if they had physical or mental disabilities or a language barrier that prevented them from understanding the consent process. In addition, dentists were allowed to exclude new patients (99 percent of the participants had had at least one dental visit before the enrollment date).

All PRECEDENT studies must have the approval of the institutional review boards (IRBs) of the two institutions involved, UW and OHSU. The two universities’ IRBs have a reciprocity agreement by which they recognize each other’s reviews and which allows for review conducted solely by either institution. Because the study’s principal investigator (T.J.H.) works at OHSU, the OHSU IRB was chosen to review and subsequently approved the protocol for this study.

Data collection

As a part of the process of signing up with Northwest PRECEDENT, dentists completed questionnaires about themselves and their practices. Information collected included dentist’s age, sex, race, ethnicity and number of years practicing dentistry, the community setting (rural/suburban/urban), practice arrangement (private group or solo practice, managed care, community clinic or other), practice location (Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Utah or Washington), and number of dentists in the practice, as well as the days of practice and the number of patients seen per week.

For this particular study, dentists completed a clinical research form for each patient, collecting data regarding diagnosis of and treatments for several oral conditions by means of a clinical examination, an interview with the patient and a review of the patient’s dental chart. During the clinical examination, dentists collected information regarding malocclusions and tooth wear and asked patients about use of intraoral appliances and history of dental treatment–related herpes or aphthous ulcers. They also asked patients about their age, sex, race, ethnicity and reason for the visit. They recorded treatments started or completed at the patient’s visit. During the chart review, dentists collected information about the number of teeth and any diagnosis of periodontal diseases, dental caries, pulpitis, oral cancer, leukoplakia and orofacial pain in the preceding 12 months. Through the chart review, dentists or members of their staff obtained data regarding dental prophylaxis and preventive, restorative and endodontic treatments performed in the previous 12 months, as well as data regarding the presence of fixed and removable dentures and implants.

Dentists based each patient’s Angle classification on the relationship of his or her right and left permanent first molars, as follows:

Angle Class I occlusion if the relationship of both was Class I;

Angle Class II occlusion if the relationship of one or both was Class II;

Angle Class III occlusion if the relationship of one or both was Class III, but not Class II.

We considered open bite to be present when the dentist observed it in either the anterior (cuspids or incisors) or the posterior (molars or premolars) of the mouth. If one or more teeth had moderate to severe wear facets (loss of 1 millimeter or more of tooth structure), we considered the patient to have occlusal or incisal tooth wear. We defined dental treatment–related herpes or aphthous ulcer as a patient’s report of development of cold sores or canker sores (always, sometimes or rarely) within three days of undergoing dental treatments.

If during the preceding 12 months (including the current visit) the patient’s dental chart had a record of any of the following oral conditions, we considered the diagnosis to be positive:

gingivitis: bleeding on probing;

periodontal bone loss: any bone loss;

periodontitis: three or more periodontal pockets with probing depths greater than 3 mm and greater than 5 mm after full-mouth periodontal probings;

dental caries: one or more new caries lesions, excluding white spots;

pulpitis: irreversible pulpitis or pulpotomy or pulpectomy of primary teeth;

oral cancer: confirmed biopsy results;

orofacial pain: patient’s complaint of earaches, neck pain, pain in the jaw, clicking or popping, or sore or painful jaw muscles or a diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis.

We classified types of pain as dentoalveolar (dental and periodontal abscesses, irreversible pulpitis and other tooth-related pain), musculoligamentous (arthralgia, myalgia or other symptoms of temporomandibular joint disorders), soft-tissue (aphthous ulcers, herpes and burning mouth syndrome), neurological (headache and migraine) and nonspecific (diffuse pain).

If within the preceding 12 months the patient’s dental chart had a record of the following treatments, we considered them to have been administered:

dental prophylaxis;

preventive treatment: sealants placed in molars or premolars and topical application of fluoride (varnish or gel);

restorative treatment: direct or indirect restorations placed because of new dental caries;

endodontic treatment: root canal therapy, pulpotomy or pulpectomy.

If during the clinical examination the patient reported having received any of the following treatments at this or another dental office, we considered them to have been administered:

orthodontic treatment: either any tooth movement ever performed or an intraoral appliance made for orthodontic reasons;

occlusal splint treatment: intraoral appliances provided because of bruxism, grinding, clenching and musculoligamentous pain, either associated or not associated with temporomandibular joint disorders.

Members of the dental practice staff or the dentists themselves entered data into an Internet-based electronic data entry system. Upon completion of data collection and entry, dentists and staff returned a questionnaire evaluating their satisfaction with the study and the impact on their practice. We resolved inconsistencies in the data entry by means of communication between the research coordinators (M.R., among others) and the practice staff. The research coordinators visited a total of 18 randomly selected practices to monitor the research conduct and the quality of the data and observed very good agreement between the dental charts and the data entered in the electronic data entry system (98.2 percent agreement, based on 60 errors among 3,294 data values checked).

Statistical analysis

We examined the distribution of the sociodemographic characteristics of dentists and patients, the oral health conditions of the patients and the treatments provided in the past 12 months by using descriptive statistics. To take into account the clustering of patients within practices, we used a statistical method to calculate 95 percent confidence intervals that involved the Taylor series linearization method from the statistical sample survey software program “proc surveyfreq” procedure in SAS 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

RESULTS

Dentists’ characteristics

One hundred one Northwest PRECEDENT general dentists participated in the study. Table 1 shows characteristics of the dentists and their practices. Nearly one-half—48.5 percent—of the general dentists were 51 to 60 years old, 13.9 percent were female and 76 percent were non-Hispanic white. More than one-half—54.4 percent—had practiced dentistry for more than 20 years.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Northwest PRECEDENT* general dentists and practices.

| CHARACTERISTIC | PERCENTAGE (NO. OF PRACTICES = 101†) | 95 PERCENT CI‡ |

|---|---|---|

|

Dentists | ||

| Age in years | ||

| 30 or younger | 5.0 | 0.6–9.3 |

| 31–40 | 21.8 | 13.6–30.0 |

| 41–50 | 19.8 | 11.9–27.7 |

| 51–60 | 48.5 | 38.6–58.4 |

| Older than 60 | 5.0 | 0.6–9.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 13.9 | 7.0–20.7 |

| Male | 86.1 | 79.3–93.0 |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 76.0 | 67.5–84.5 |

| White (ethnicity unreported) | 8.0 | 2.6–13.4 |

| Hispanic white | 2.0 | 0.0–4.8 |

| Asian | 8.0 | 2.6–13.4 |

| African American | 2.0 | 0.0–4.8 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.0 | 0.0–3.0 |

| Other or multiple races | 3.0 | 0.0–6.4 |

| Years in practice | ||

| Five or fewer | 12.9 | 6.2–19.5 |

| 6–15 | 20.8 | 12.7–28.8 |

| 16–20 | 11.9 | 5.5–18.3 |

| 21–25 | 26.7 | 18.0–35.5 |

| More than 25 | 27.7 | 18.8–36.6 |

|

Practices | ||

| Practice type | ||

| Private solo practice | 83.2 | 75.7–90.6 |

| Private group practice | 10.9 | 4.7–17.1 |

| Community clinic | 4.0 | 0.1–7.8 |

| Managed care clinic | 1.0 | 0.0–3.0 |

| Other | 1.0 | 0.0–3.0 |

| No. of dentists in the practice | ||

| One | 77.2 | 68.9–85.5 |

| Two or three | 17.8 | 10.2–25.4 |

| More than three | 5.0 | 0.6–9.3 |

| No. of days of practicing per week | ||

| Fewer than four | 6.9 | 1.9–12.0 |

| Four | 83.2 | 75.7–90.6 |

| More than four | 9.9 | 4.0–15.8 |

| No. of patients seen per week | ||

| One to 40 | 28.6 | 19.5–37.7 |

| 41 to 50 | 20.4 | 12.3–28.5 |

| More than 50 | 51.0 | 40.9–61.1 |

| Community type | ||

| Urban | 21.5 | 13.0–30.0 |

| Suburban | 46.2 | 35.9–56.6 |

| Rural | 32.3 | 22.6–41.9 |

| Practice location (state) | ||

| Washington | 42.6 | 32.8–52.4 |

| Oregon | 22.8 | 14.5–31.1 |

| Utah | 13.9 | 7.0–20.7 |

| Idaho | 12.9 | 6.2–19.5 |

| Montana | 7.9 | 2.6–13.3 |

PRECEDENT: Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry.

Information was not reported for race/ethnicity (n = 1), community type (n = 8) and patients per week (n = 3). Denominators in those categories were reduced accordingly.

CI: Confidence interval.

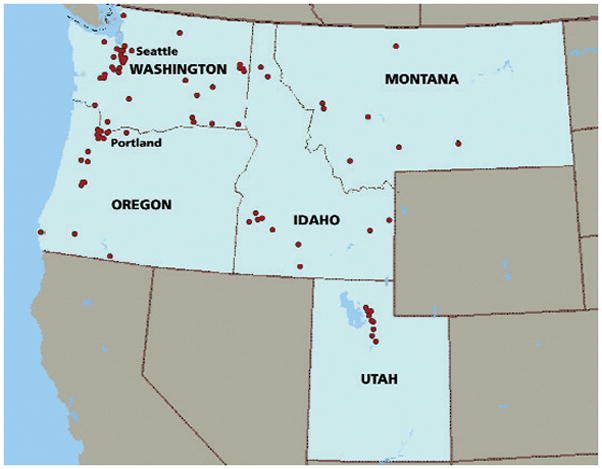

In terms of practice type, 83.2 percent of the dentists had private solo practices, 10.9 percent practiced in group practices and 4 percent practiced in community clinics. The average number of patients seen per week was more than 50 in 51 percent of the practices, from 41 to 50 in 20.4 percent of the practices and 40 or fewer in 28.6 percent of the practices. A majority—83.2 percent—of the dentists practiced four days per week. Slightly more than 60 percent of the practices were in urban or suburban communities, but 32.3 percent were in rural areas. The state with the largest number of practices was Washington (42.6 percent), followed by Oregon, Utah, Idaho and Montana (Table 1 and Figure).

Figure.

Map of practice locations for Northwest Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry (PRECEDENT) general dentists participating in the study (each dot indicates a ZIP code representing at least one PRECEDENT practice).

Patients’ characteristics and conditions

There were 1,943 patients enrolled in the study. Table 2 (page 895) presents their characteristics and oral health conditions. The vast majority of the patients visiting the dental practices were between 18 and 64 years of age, with 36.7 percent aged 45 to 64 years and 33.9 percent aged 18 to 44 years. Fourteen percent of the patients were children and adolescents and 15.3 percent were elderly. Fifty-five percent of the patients were female and 84.2 percent were non-Hispanic white.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics and conditions of patients from Northwest PRECEDENT* practices.

| CHARACTERISTIC OR CONDITION | CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS (n = 273) |

ADULTS (n = 1,668) |

ALL† (N = 1,943) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI‡ | n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

|

Characteristics of Patients | |||||||||

| Age in years | |||||||||

| 3 to 11 | 143 | 52.4 | 45.6–59.1 | —§ | — | — | 143 | 7.4 | 5.5–9.2 |

| 12 to 17 | 130 | 47.6 | 40.9–54.4 | — | — | — | 130 | 6.7 | 5.2–8.2 |

| 18 to 44 | — | — | — | 658 | 39.4 | 35.9–43.0 | 658 | 33.9 | 30.9–36.9 |

| 45 to 64 | — | — | — | 713 | 42.7 | 40.0–45.5 | 713 | 36.7 | 34.0–39.5 |

| 65 or older | — | — | — | 297 | 17.8 | 14.9–20.8 | 297 | 15.3 | 12.6–18.0 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 140 | 51.3 | 46.3–56.2 | 730 | 43.8 | 41.3–46.3 | 872 | 44.9 | 42.5–47.2 |

| Female | 133 | 48.7 | 43.8–53.7 | 938 | 56.2 | 53.7–58.7 | 1,071 | 55.1 | 52.8–57.5 |

| Race or ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 175 | 68.9 | 56.8–81.0 | 1,383 | 86.6 | 83.9–89.3 | 1,560 | 84.2 | 80.5–87.8 |

| Hispanic white | 3 | 1.2 | 0.0–2.5 | 33 | 2.1 | 1.3–2.9 | 36 | 1.9 | 1.2–2.7 |

| Asian | 9 | 3.5 | 0.1–7.0 | 34 | 2.1 | 0.9–3.3 | 43 | 2.3 | 0.9–3.7 |

| African American | 7 | 2.8 | 0.0–5.5 | 20 | 1.3 | 0.4–2.1 | 27 | 1.5 | 0.4–2.5 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 | 1.2 | 0.0–2.5 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.2–0.8 | 11 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.0 |

| Other or multiple races | 57 | 22.4 | 10.6–34.3 | 119 | 7.5 | 5.5–9.4 | 176 | 9.5 | 6.5–12.5 |

|

Condition Revealed by Means of Clinical Examination | |||||||||

| Angle classification | |||||||||

| Class I | 159 | 69.1 | 62.5–75.7 | 1,008 | 67.6 | 63.9–71.3 | 1,167 | 67.7 | 64.2–71.2 |

| Class II | 54 | 23.5 | 17.7–29.3 | 339 | 22.7 | 19.5–26.0 | 394 | 22.9 | 19.8–25.9 |

| Class III | 17 | 7.4 | 3.7–11.1 | 145 | 9.7 | 7.8–11.6 | 163 | 9.5 | 7.7–11.3 |

| Anterior or posterior open bite | 41 | 15.0 | 10.8–19.2 | 197 | 11.8 | 9.7–13.9 | 238 | 12.2 | 10.3–14.2 |

| Tooth wear (one tooth or more) | 88 | 32.2 | 22.7–41.7 | 1,107 | 66.6 | 62.0–71.2 | 1,197 | 61.8 | 57.1–66.5 |

| Dental treatment–related herpes or aphthous ulcer | 10 | 3.8 | 1.6–6.0 | 104 | 6.3 | 4.6–8.1 | 114 | 6.0 | 4.4–7.5 |

|

Condition Revealed by Means of 12-Month Chart Review | |||||||||

| Dentition | |||||||||

| Primary teeth | 41 | 15.0 | 8.4–21.7 | — | — | — | 41 | 2.1 | 1.0–3.3 |

| Mixed dentition | 107 | 39.2 | 32.5–45.9 | 9 | 0.5 | 0.2–0.9 | 116 | 6.0 | 4.6–7.3 |

| Permanent teeth | 125 | 45.8 | 39.3–52.3 | 1,643 | 98.9 | 98.4–99.4 | 1,770 | 91.4 | 89.4–93.4 |

| Edentulous | — | — | — | 10 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.0 | 10 | 0.5 | 0.2–0.8 |

| Tooth loss (one or more permanent teeth) | 22 | 9.5 | 6.0–13.0 | 878 | 52.8 | 49.6–56.0 | 902 | 47.6 | 44.3–50.8 |

| Dental caries | 157 | 57.5 | 50.6–64.5 | 918 | 55.1 | 51.3–58.8 | 1,077 | 55.5 | 51.9–59.0 |

| Pulpitis | 13 | 4.8 | 2.1–7.4 | 146 | 8.8 | 6.7–10.8 | 159 | 8.2 | 6.3–10.1 |

| Gingivitis | 91 | 37.6 | 28.7–46.5 | 951 | 60.5 | 55.1–66.0 | 1,044 | 57.5 | 52.3–62.8 |

| Periodontal bone loss | 2 | 0.8 | 0.0–1.9 | 632 | 40.4 | 35.6–45.2 | 635 | 35.0 | 30.7–39.3 |

| Leukoplakia | 1 | 0.4 | 0.0–1.1 | 43 | 2.6 | 1.1–4.2 | 44 | 2.3 | 1.0–3.6 |

| Orofacial pain | 13 | 5.0 | 2.3–7.7 | 269 | 16.4 | 13.6–19.2 | 282 | 14.8 | 12.4–17.3 |

| Type of orofacial pain | |||||||||

| Dentoalveolar | 11 | 4.2 | 1.6–6.8 | 152 | 9.3 | 7.1–11.4 | 163 | 8.6 | 6.6–10.5 |

| Musculoligamentous | 2 | 0.8 | 0.0–1.8 | 110 | 6.7 | 4.6–8.8 | 112 | 5.9 | 4.0–7.7 |

| Soft-tissue | 1 | 0.4 | 0.0–1.1 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.2–0.8 | 9 | 0.5 | 0.2–0.8 |

| Neurological | 0 | 0 | — | 12 | 0.7 | 0.2–1.3 | 12 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.1 |

| Nonspecific | 0 | 0 | — | 10 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.0 | 10 | 0.5 | 0.2–0.8 |

PRECEDENT: Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry.

Information was unreported for age (two participants), race (19 children/adolescents, 71 adults), Angle classification (two children/adolescents, 31 adults; not applicable because of absence of permanent first molar: 41 children/adolescents, 145 adults), tooth wear (six adults), aphthous ulcer (nine children/adolescents, 30 adults), dentition (six adults), tooth loss (six children; not applicable because of presence of only primary dentition: 41 children), dental caries (one adult), gingivitis (31 children/adolescents, 97 adults), periodontal bone loss (26 children/adolescents, 104 adults), leukoplakia (14 children/adolescents, 45 adults) and orofacial pain (13 children/adolescents, 29 adults). Denominators in those categories were reduced accordingly.

CI: Confidence interval.

Dashes (—) indicate “not applicable.”

In terms of their oral health conditions (Table 2), the majority of the participants had a Class I molar relationship (67.7 percent), 22.9 percent had a Class II relationship and 9.5 percent had a Class III relationship. Six percent had a history of dental treatment–related herpes or aphthous ulcers.

Among the children and adolescents, 39.2 percent had mixed dentition and 15 percent had only primary teeth. Among the participants with primary teeth, 55.9 percent had crowding in the mixed dentition and 45 percent had spacing in the anterior primary teeth. More than one-half—52.8 percent—of the adults had at least one missing tooth and 0.6 percent were edentulous. The prevalences of dental caries and pulpitis in the preceding 12 months were 57.5 percent and 4.8 percent for children and adolescents and 55.1 percent and 8.8 percent for adults, respectively. More than one-third—37.6 percent—of children and adolescents and more than one-half—60.5 percent—of the adults had a record of gingivitis. In adults, 40.4 percent had a history of periodontal bone loss, but only 0.8 percent of children had bone loss. In a subset of the data (not shown), of the 1,052 adults who had undergone full-mouth periodontal probing (63 percent of the total adult study population), 73.2 percent (or 46.2 percent of the total adult study population) had periodontal pockets with probing depths greater than 3 mm in three or more teeth; 17.5 percent (or 11 percent of the total adult study population) had periodontal pockets with probing depths greater than 5 mm in three or more teeth. No patients had records of oral cancer. Overall, two percent of the patients had a record of leukoplakia. The overall proportion of patients experiencing orofacial pain was 14.8 percent (prevalences of 16.4 percent in adults and 5.0 percent in children and adolescents). Among the non–mutually exclusive categories of orofacial pain, 8.6 percent of patients had dentoalveolar pain, 5.9 percent musculoligamentous pain, 0.5 percent soft-tissue pain, 0.6 percent neurological pain and 0.5 percent nonspecific pain (Table 2).

Among the treatments performed in the preceding 12 months, shown in Table 3 (page 896), prophylaxis had been performed in 85.3 percent of patients. Preventive treatment had been received by 33.5 percent of patients, including fluoride varnish (12.3 percent), topical application of fluoride (23.1 percent) and sealants on molars and premolars (4.8 percent). Almost one-half—48.5 percent—of the participants had undergone restorative treatments within the past 12 months, with 34.5 percent of the participants having received one or more resin-based composite restorations, 11.4 percent having received amalgam restorations and 9.3 percent having received indirect restorations. Endodontic treatments had been performed in 9.7 percent of the participants. In terms of occlusal treatment, 30.2 percent of the participants had ever received orthodontic treatment, and 7.4 percent had ever used occlusal splints (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Dental treatments performed in the past 12 months in patients from Northwest PRECEDENT* practices.

| TREATMENT | CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS (n = 273) |

ADULTS (n = 1,668) |

ALL† (N = 1,943) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI‡ | n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

| Prophylaxis | 252 | 94.0 | 89.7–98.4 | 1,372 | 83.9 | 80.7–87.1 | 1,626 | 85.3 | 82.3–88.3 |

| Preventive Treatment | 239 | 88.5 | 83.5–93.5 | 401 | 24.5 | 18.0–31.0 | 640 | 33.5 | 27.6–39.4 |

| Fluoride varnish | 87 | 32.6 | 23.8–41.4 | 146 | 9.0 | 4.7–13.4 | 233 | 12.3 | 8.0–16.6 |

| Topical application of fluoride | 168 | 62.9 | 53.9–71.9 | 267 | 16.5 | 10.8–22.2 | 435 | 23.1 | 17.7–28.4 |

| Sealant | 73 | 27.3 | 21.8–32.9 | 19 | 1.2 | 0.5–1.8 | 92 | 4.8 | 3.5–6.1 |

| Restorative Treatment | 139 | 50.9 | 44.0–57.9 | 802 | 48.1 | 44.6–51.6 | 943 | 48.5 | 45.2–51.9 |

| Composite | 103 | 37.7 | 29.6–45.9 | 565 | 33.9 | 30.0–37.8 | 670 | 34.5 | 30.7–38.3 |

| Amalgam | 39 | 14.3 | 7.6–21.0 | 182 | 10.9 | 8.2–13.6 | 222 | 11.4 | 8.7–14.1 |

| Glass ionomer | 10 | 3.7 | 0.4–7.0 | 49 | 2.9 | 1.7–4.2 | 59 | 3.0 | 1.8–4.3 |

| Indirect | 3 | 1.1 | 0.0–2.4 | 177 | 10.6 | 8.3–12.9 | 180 | 9.3 | 7.2–11.3 |

| Temporary | 2 | 0.7 | 0.0–1.7 | 15 | 0.9 | 0.3–1.5 | 17 | 0.9 | 0.3–1.5 |

| Endodontic Treatment | 6 | 2.2 | 0.4–4.0 | 182 | 10.9 | 8.9–12.9 | 189 | 9.7 | 8.0–11.5 |

| Orthodontic Treatment (Ever) | 72 | 26.6 | 19.8–33.3 | 509 | 30.8 | 28.3–33.3 | 581 | 30.2 | 27.7–32.7 |

| Occlusal Splints (Ever) | 0 | 0 | —§ | 142 | 8.6 | 6.2–11.1 | 142 | 7.4 | 5.2–9.6 |

PRECEDENT: Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry.

Information was unreported for age (two participants), prophylaxis (five children/adolescents, 32 adults), preventive treatment (three children/adolescents, 31 adults), topical application of fluoride (six children/adolescents, 49 adults), fluoride varnish (six children/adolescents, 51 adults), sealant (six children/adolescents, 37 adults), orthodontic treatment (two children/adolescents, 17 adults) and occlusal splints (four children/adolescents, 25 adults). Denominators in those categories were reduced accordingly.

CI: Confidence interval.

Dashes (—) indicate “not applicable.”

Reasons for dental visits

The main reason for the sampled dental visit is given in Table 4 (page 897). The most common reasons for a dental visit were related to maintenance of oral health, including dental checkup or examination (21.8 percent) and prophylaxis (29 percent). In other types of treatment, 20.9 percent of the patients received a restorative treatment for dental caries or tooth fracture during the visit, 16.4 percent received prosthodontic therapy (19 percent of adults and less than 1 percent of children and adolescents) and 10.7 percent received other treatments.

TABLE 4.

Main reason for visiting a general dentist among patients of dentists in Northwest PRECEDENT.*

| REASON FOR VISIT TO DENTIST | CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS (n = 273) |

ADULTS (n = 1,668) |

ALL (N = 1,943) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI† | n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

| Maintenance of Oral Health | 171 | 62.6 | 55.7–69.6 | 832 | 49.9 | 45.6–54.1 | 1,003 | 51.6 | 47.7–55.6 |

| Examination or checkups | 97 | 35.5 | 27.9–43.1 | 326 | 19.5 | 15.4–23.7 | 423 | 21.8 | 17.7–25.9 |

| Prophylaxis | 62 | 22.7 | 15.1–30.3 | 502 | 30.1 | 25.0–35.2 | 564 | 29.0 | 24.0–34.1 |

| Caries prevention (sealants, remineralization) | 12 | 4.4 | 0.6–8.1 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.0–0.5 | 16 | 0.8 | 0.2–1.4 |

| Restorative Dentistry | 74 | 27.1 | 21.1–33.1 | 340 | 20.4 | 17.3–23.5 | 415 | 21.4 | 18.4–24.3 |

| Restorative treatment (caries or fractures) | 74 | 27.1 | 21.1–33.1 | 331 | 19.8 | 16.8–22.9 | 406 | 20.9 | 18.0–23.8 |

| Esthetic treatment (bleaching) | 0 | 0 | —‡ | 9 | 0.5 | 0.2–0.9 | 9 | 0.5 | 0.1–0.8 |

| Endodontic Therapy | 2 | 0.7 | 0.0–1.8 | 33 | 2.0 | 1.2–2.8 | 35 | 1.8 | 1.1–2.5 |

| Endodontic treatment | 2 | 0.7 | 0.0–1.8 | 33 | 2.0 | 1.2–2.8 | 35 | 1.8 | 1.1–2.5 |

| Periodontal Therapy | 0 | 0 | — | 37 | 2.2 | 1.3–3.1 | 37 | 1.9 | 1.1–2.7 |

| Periodontal examination | 0 | 0 | — | 5 | 0.3 | 0.0–0.6 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.0–0.5 |

| Periodontal treatment or maintenance | 0 | 0 | — | 32 | 1.9 | 1.1–2.8 | 32 | 1.6 | 0.9–2.4 |

| Prosthodontic Therapy | 1 | 0.4 | 0.0–1.1 | 317 | 19.0 | 16.8–21.2 | 318 | 16.4 | 14.4–18.3 |

| Replacement of teeth (fixed or removable dentures) | 1 | 0.4 | 0.0–1.1 | 309 | 18.5 | 16.3–20.7 | 310 | 16.0 | 14.0–17.9 |

| Implants | 0 | 0 | — | 8 | 0.5 | 0.1–0.8 | 8 | 0.4 | 0.1–0.7 |

| Malocclusion Therapy | 18 | 6.6 | 2.1–11.1 | 29 | 1.7 | 0.9–2.6 | 47 | 2.4 | 1.4–3.5 |

| Orthodontic examination or treatment | 18 | 6.6 | 2.1–11.1 | 18 | 1.1 | 0.4–1.7 | 36 | 1.9 | 0.9–2.8 |

| Occlusal adjustment or guard | 0 | 0 | — | 11 | 0.7 | 0.2–1.2 | 11 | 0.6 | 0.1–1.0 |

| Orofacial Medicine/Oral Surgery | 3 | 1.1 | 0.0–2.3 | 49 | 2.9 | 1.5–4.3 | 52 | 2.7 | 1.4–3.9 |

| Oral surgery | 3 | 1.1 | 0.0–2.3 | 33 | 2.0 | 1.3–2.7 | 36 | 1.9 | 1.2–2.5 |

| Temporomandibular joint examination or treatment | 0 | 0 | — | 16 | 1.0 | 0.0–2.2 | 16 | 0.8 | 0.0–1.9 |

| Emergency Care | 4 | 1.5 | 0.0–3.2 | 31 | 1.9 | 1.1–2.6 | 36 | 1.9 | 1.1–2.6 |

| Toothache | 4 | 1.5 | 0.0–3.2 | 31 | 1.9 | 1.1–2.6 | 36 | 1.9 | 1.1–2.6 |

PRECEDENT: Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry.

CI: Confidence interval.

Dashes (—) indicate “not applicable.”

Dentists’ satisfaction with the study and impact on the practice

In feedback collected on completion of the study, the acceptance of the study procedures was good among the general dentists who returned the evaluation questionnaire (n = 55). Many of them, 93 percent, considered that the time required to participate in the study was acceptable; 96 percent considered that completing the study was not difficult; and 98 percent rated the instructions on how to implement the study (training sessions and study materials such as manual of operations, questionnaire and telephone script) as good to excellent.

DISCUSSION

The results of the first Northwest PRECEDENT study provided a snapshot of the network, including estimates of the burden of disease and the amount of treatment in active patients. This study not only helped to activate the network and provide the dentist-investigators with a satisfying experience conducting research in their practices, but it also provided an opportunity to estimate the prevalence of various oral conditions and treatments in the Northwest PRECEDENT population and to compare the findings with what is known at the national level and regional levels.

Dentists’ demographics

The age distribution of Northwest PRECEDENT dentists is slightly different from national estimates. While one in four dentists in the network was younger than 40 years, one in eight dentists in the 2006 American Dental Association Survey of Dental Practice was in that age group.8 The network had fewer dentists older than 59 years—5 percent—than the 22 percent reported in the same survey. The sex distribution was similar between the network (14 percent female) and the Survey of Dental Practice. Assuming the network dentists began practicing dentistry the year after their graduation, the practicing experience of the network dentists is slightly shorter then national estimates: about 55 percent of the network dentists had more than 20 years of practice, contrasted with 66 percent of the dentists who participated in the national survey.8

When compared with the population of practicing dentists in the same five-state region, minority races were overrepresented among network dentists, with a proportion of 16 percent (including Asian, an important minority population in the Northwest), which is higher than that of Washington, the Northwest PRECEDENT state with the highest proportion of minority dentists (13 percent).9 The proportion of Northwest PRECEDENT dentists practicing in rural communities (32 percent) is several times higher than estimates for the nation (less than 5 percent).10 The geographical distribution of the network dentists across the area parallels the distribution of active general dentists in the region,9 with clustering in the main population centers.

In summary, Northwest PRECEDENT dentists and their practices were relatively comparable demographically with general dentists and their practices in the rest of the country and particularly in the network five-state region but with slightly higher proportions of younger dentists, minority races and practices located in rural communities. This demographic picture is consistent with Northwest PRECEDENT’s meeting its stated enrollment goals to enroll enough minority dentists and rural practices so as to provide meaningful data in those categories.

Patients’ demographics

The age and sex distribution of the patients visiting Northwest PRECEDENT practices were similar to national estimates of those of patients of general dentists,8 with one in seven patients being a child or adolescent, one in seven patients being elderly and more female than male patients visiting general dentists. The proportion of patients of minority races or ethnicities visiting the network dentists was slightly lower than national estimates of non-white patients visiting dentists in the preceding year: 16 percent in the Northwest PRECEDENT network and 20 percent in the CDC’s 2004 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey (as cited by Kapp and colleagues11).

Dental conditions

By comparing the prevalence of oral diseases among the Northwest PRECEDENT patients with that among the overall population, we can gain some idea of how patients visiting their dentists differ from the overall population. Because available national data are for adults, we used only prevalences among adults for our comparisons. Approximately one-half—52.8 percent—of the Northwest PRECEDENT adult patients had lost at least one tooth, whereas 60 percent among the overall adult population had incomplete dentition.12 Approximately one in two Northwest PRECEDENT adult patients had been diagnosed with dental caries in the previous year, while in the overall population one in four people had untreated dental caries.6 While this level of caries may seem rather high, it is noteworthy that this is in a population seeking care, with 20 percent specifically seeking restorative treatment. Among adult patients in Northwest PRECEDENT, 46.2 percent had three or more teeth with periodontal pockets 3 mm or greater in depth, and 11 percent had three or more teeth with pockets 5 mm or greater in depth. These numbers appear to compare well with prevalences for less stringent definitions of two or more sites with periodontal pocket probing depths of 3 mm or greater and 4 mm or greater in the general adult population (47 percent and 11 percent, respectively).13 However, almost one-half of the patients had not undergone a periodontal probing in the preceding year, so reported periodontal pocket levels often were incomplete.

Treatments

Patients visiting Northwest PRECEDENT general dental practices received two times more restorative treatments in the previous year than national estimates showed for all patients visiting general dentists and specialists (82 percent of whom visited general dentists).14 Possible explanations for this finding are the higher prevalence of dental caries and the lower prevalence of tooth loss in the Northwest PRECEDENT patient population. Rates of prophylaxis and preventive treatment were similar between this study and national estimates.14 Endodontic treatment rates were higher than national estimates (9.7 percent versus 4.6 percent),14 although our study did not include treatment provided by specialists. Orthodontic treatment rates were slightly higher than national estimates (29 percent versus 20 percent).15

Reasons for dental visit

Maintenance of oral health was patients’ main reason for visiting Northwest PRECEDENT general dentists (Table 4). This finding is corroborated by other studies in the United States16 and elsewhere.17,18 Examination, prophylaxes and prevention composed 65 percent and 70 percent of the dental services provided by general dentists in Washington state in 200116 and in Australia in the period from 1993 to 1994,17 respectively. While the proportion of restorative services provided by Northwest PRECEDENT general dentists is similar to that provided by Washington state general dentists, the proportion was lower than that provided by Australian general dentists.

Feasibility of practice-based research

This survey of practice, dentists’ and patients’ characteristics provided evidence that doing research in busy private and community health practices was feasible, and the participating dentists and staff members generally indicated high satisfaction with their experience. Whereas there was initial concern that participation in network studies might be viewed negatively by patients, anecdotal feedback from several dentists indicated that instead it seemed to generate an atmosphere of respect and better rapport with their patients. Limitations of this study include its use of clinical definitions and measurements as used in practice without efforts to standardize all of the dentists. In addition, data collected from dental charts may have led to underestimation of the prevalence of oral conditions and treatments if the records did not indicate the diagnosis of certain conditions during the preceding 12 months or if patients had less than one year’s worth of records.

CONCLUSION

This first study conducted by Northwest PRECEDENT provided valid estimates of dentists’ and patients’ characteristics among network practices that will be valuable in planning new and more complex studies such as randomized clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors received support from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research via grants DE016750 and DE016752.

The authors are grateful for the invaluable contributions of the dentist-investigator members of the Northwest Practice-based Research Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry (Northwest PRECEDENT) and their staff members, on whose behalf the manuscript of this article was submitted.

ABBREVIATION KEY

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- HIPAA

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- IRB

Institutional review board

- NIDCR

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- OHSU

Oregon Health & Science University

- PBRN

Practice-based research network

- PRECEDENT

Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry

- UW

University of Washington

Footnotes

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

The authors encourage all practitioners who are interested in learning more about the research network and in inquiring about how to participate to visit the network’s Web site at “www.nwprecedent.net”.

Contributor Information

Dr. Timothy A. DeRouen, Email: derouen@u.washington.edu, Department of Dental Public Health Sciences; a professor, Department of Biostatistics; and executive associate dean for research and academic affairs, School of Dentistry, University of Washington, PO Box 357480, Seattle, Wash. 98195.

Dr. Joana Cunha-Cruz, Department of Dental Public Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Thomas J. Hilton, School of Dentistry, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

Dr. Jack Ferracane, Department of Restorative Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

Dr. Joel Berg, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, School of Dentistry, University of Washington, Seattle.

Ms. Lingmei Zhou, Department of Dental Public Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Washington, Seattle.

Ms. Marilynn Rothen, Regional Clinical Dental Research Center, University of Washington, Seattle.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health. NIH roadmap for medical research. Bethesda, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2009. [Accessed March 16, 2009]. http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/overview.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuska B. NIDCR awards grants for new practice-based initiative. Bethesda, Md: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2005. [Accessed April 11, 2010]. www.nidcr.nih.gov/Research/ResearchResults/NewsReleases/ArchivedNewsReleases/NRY2005/PR03312005.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Rindal DB, Pihlstrom DJ, Benjamin PL, Wallace MC DPBRN Collaborative Group. The creation and development of the dental practice-based research network. JADA. 2008;139(1):74–81. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ship JA, Curro FA, Caufield PW, et al. Practicing dentistry using findings from clinical research: you are closer than you think. JADA. 2006;137(11):1488–1490. 1492–1494. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ publication 01-P020. Rockville, Md: AHRQ; [Accessed April 11, 2010]. AHRQ practice-based research networks (PBRNs): fact sheet. Current as of May 2006. www.ahrq.gov/research/pbrn/pbrnfact.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Barker LK, Canto MT, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for dental caries, dental sealants, tooth retention, edentulism, and enamel fluorosis—United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2005;54(3):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeRouen TA, Hujoel P, Leroux B, et al. Northwest Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry. Preparing practicing dentists to engage in practice-based research. JADA. 2008;139(3):339–345. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Dental Association Survey Center. 2006 Survey of Dental Practice: Characteristics of Dentists in Private Practice and Their Patients. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Dental Association Survey Center. Distribution of Dentists in the United States by Region and State, 2001. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wall TP, Brown LJ. The urban and rural distribution of dentists, 2000. JADA. 2007;138(7):1003–1011. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapp JM, Boren SA, Yun S, LeMaster J. Diabetes and tooth loss in a national sample of dentate adults reporting annual dental visits. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(3):A59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus SE, Drury TF, Brown LJ, Zion GR. Tooth retention and tooth loss in the permanent dentition of adults: United States, 1988–1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75 doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S08. special no:684–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher MA, Taylor GW, Shelton BJ, Debanne SM. Predictive values of self-reported periodontal need: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J Periodontol. 2007;78(8):1551–1560. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manski RJ, Brown E. MEPS Chartbook No. 17. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. Dental Use, Expenses, Dental Coverage, and Changes, 1996 and 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunelle JA, Bhat M, Lipton JA. Prevalence and distribution of selected occlusal characteristics in the US population, 1988–1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75(special issue):706–713. doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.del Aguila MA, Leggott PJ, Robertson PB, Porterfield DL, Felber GD. Practice patterns among male and female general dentists in a Washington State population. JADA. 2005;136(6):790–796. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennan DS, Spencer AJ, Szuster FS. Service provision patterns by main diagnoses and characteristics of patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28(3):225–233. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuttall NM. The cost of general dental service treatment provided for dentate adults in Scotland. Br Dent J. 1984;157(5):160–164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]