Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the performance of an algorithm used to measure the volumetric breast density (VBD) from digital mammograms. The algorithm is based on the calibration of the detector signal versus the thickness and composition of breast-equivalent phantoms. The baseline error in the density from the algorithm was found to be 1.25 ± 2.3% VBD units (PVBD) when tested against a set of calibration phantoms, of thicknesses 3–8 cm, with compositions equivalent to fibroglandular content (breast density) between 0% and 100% and under x-ray beams between 26 kVp and 32 kVp with a Rh/Rh anode/filter. The algorithm was also tested against images from a dedicated breast computed tomography (CT) scanner acquired on 26 volunteers. The CT images were segmented into regions representing adipose, fibroglandular and skin tissues, and then deformed using a finite-element algorithm to simulate the effects of compression in mammography. The mean volume, VBD and thickness of the compressed breast for these deformed images were respectively 558 cm3, 23.6% and 62 mm. The displaced CT images were then used to generate simulated digital mammograms, considering the effects of the polychromatic x-ray spectrum, the primary and scattered energy transmitted through the breast, the anti-scatter grid and the detector efficiency. The simulated mammograms were analyzed with the VBD algorithm and compared with the deformed CT volumes. With the Rh/Rh anode filter, the root mean square difference between the VBD from CT and from the algorithm was 2.6 PVBD, and a linear regression between the two gave a slope of 0.992 with an intercept of −1.4 PVBD and a correlation with R2 = 0.963. The results with the Mo/Mo and Mo/Rh anode/filter were similar.

1. Introduction

Mammographic breast density (MBD) represents the appearance of the stroma and epithelial tissue (collectively referred to as fibroglandular tissue) on the mammogram. Areas containing fibroglandular tissue are distinguished from surrounding fatty tissue due to the larger x-ray attenuation coefficient of the former (Johns and Yaffe 1987). High MBD has been identified as a strong risk factor for the development of breast cancer. Wolfe (1976, 1976a) first proposed this relationship, which has been confirmed by others (Saftlas and Szklo 1987, Heine and Malhotra 2002, 2002a, Goodwin and Boyd 1988, Boyd et al 2007), showing a two- to fourfold increase in risk between women with low and high MBD. In addition, it is more difficult to obtain an accurate interpretation of mammograms of dense breasts; there is a greater likelihood of both missed cancers and false positive results (Whitehead et al 1985, Sala et al 1998, van Gils et al 1998). The assessment of MBD is, therefore, a potentially important tool. It can be used to identify women at increased risk who could benefit from more frequent screening or the use of alternative imaging and diagnostic methods (van Gils et al 1999). Also, MBD is one of the strongest risk factors that can be modified through adjustment of other factors, such as diet (Tseng et al 2007, Takata et al 2007) and physical activity (Irwin et al 2007). A causal link between MBD and breast cancer remains to be demonstrated.

Many of the currently used tools for assessment of mammographic density rely on two-dimensional measurements and express MBD in terms of the fraction of the projected area of the breast that appears to be composed of fibroglandular tissue. It is more logical, however, that cancer risk is related to the number of fibroglandular cells, which is proportional to the volume of dense tissue in the breast and, therefore, there is an interest in the measurement of volumetric breast density (VBD). Furthermore, knowledge of breast composition is required for estimation of the radiological dose to the breast in medical imaging (Yaffe et al 2009) and a more accurate estimation of composition could improve the validity of dose estimation.

There have been many methods developed to estimate the volumetric radiological breast density. Frequently, the most practical way to obtain the VBD is from mammograms, as women frequently receive this examination for breast cancer screening. Highnam et al (1996, Highnam and Brady 1999) have developed a physics model of the complete imaging system in screen-film mammography in order to extract the thickness of fibroglandular tissue, a quantity that they refer to as hint. Van Engeland et al (2006) described a simple physical model of full-field digital mammography to calculate the VBD and have shown good agreement with breast density measurement using magnetic resonance imaging. Pawluczyk et al (2003) and Kaufhold et al (2002) have developed methods, relating the transmitted signal measured on breast tissue-equivalent calibration objects to their known thickness and compositions, and have applied this relation to estimate VBD using mammograms of breasts. Another approach, a version of the dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry technique used for bone densitometry, modified for use in the breast (Shephard et al 2002), can, in principle, offer precise measurements of the VBD at very low doses but requires a dedicated and separate procedure.

A breast density algorithm, Cumulus V, was developed as a refinement of the method by Pawluczyk et al (2003) by adapting it to digital mammography and by using a combination of measurement and modeling to estimate the compressed breast thickness (Mawdsley et al 2009, Tyson et al 2009).

For any method that attempts to quantify the mammographic density from projection images, it is necessary to test the accuracy of that method. In this work, we use volumetric attenuation data obtained with a prototype dedicated breast computed tomography (DBCT) system developed at the University of California, Davis (Boone et al 2006, 2006a, 2001, Lindfors et al 2008) to perform such a validation on the Cumulus V algorithm.

2. Materials and methods

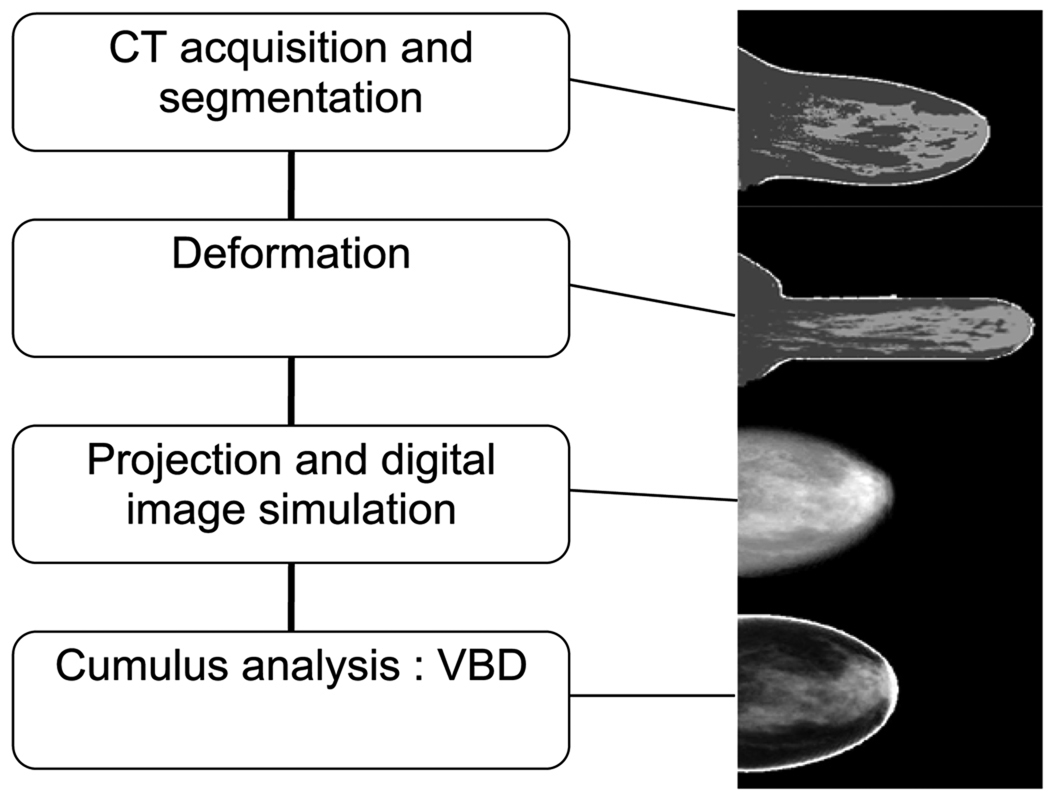

The approach used to validate Cumulus V is summarized in figure 1. Women were imaged on a prototype breast CT system (Boone et al 2006, 2006a, 2001, Lindfors et al 2008) and the CT image slices were segmented according to the major tissue types, fibroglandular, fat and skin. The CT data were then ‘deformed’ using finite-element analysis to simulate mechanical compression of the breast. The deformed breast volume was converted to x-ray attenuation coefficients, according to the tissue type, at energies such as those used in mammography and simulated projection digital mammograms were created. Finally, the simulated mammograms were analyzed with Cumulus V, and the resulting VBD was compared to the VBD from the deformed CT volume.

Figure 1.

Flowchart summary of the validation process. From top to bottom: sagittal slice from a segmented CT volume, sagittal slice from the displaced volume, negative logarithm of the simulated digital mammogram and calculated density map of the mammogram.

2.1. Breast CT

The acquisition and processing of the CT image information is depicted in figure 1. During CT imaging on the prototype CT system, the patient lies prone on a table with the breast pendant through an aperture. An x-ray tube and a flat-panel detector array rotate about the breast to acquire the projection data. The cone-beam projections are acquired at 80 kV with a tungsten target and 0.3 mm copper filtration. CT images are then reconstructed from the projection data. The images are stored as a volumetric array of x-ray attenuation coefficients, each representing tissue in a volume (voxel) with dimensions between 0.21 mm and 0.41 mm in the coronal plane, and between 0.25 mm and 0.41 mm in the sagittal plane.

The CT scans were reconstructed in terms of effective attenuation coefficients. These measurements reflect the x-ray energy fluence transmitted by the breast and absorbed by the flat-panel detector. They include the effects of x-ray scattering and beam hardening. Following image reconstruction, a ‘cupping’ correction was performed to correct for scatter and hardening artifacts.

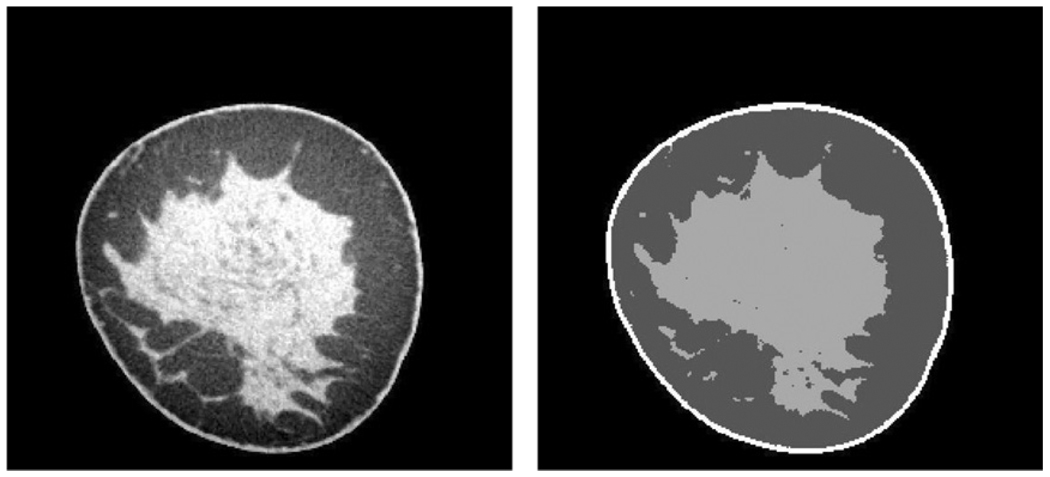

The voxels in the CT image were classified into four components: air (breast exterior), skin, adipose and fibroglandular tissue. The frequency distribution of attenuation coefficients was computed and the threshold between the breast and the air, which has low CT values, was determined. Because skin and fibroglandular tissue have similar CT values, we initially used a two-compartment Gaussian fit to segment the histogram. This allowed the determination of a threshold voxel value at the intersection of the two Gaussian distributions. To verify whether the threshold was satisfactory (in some cases the Gaussian functions were not well separated), images of central slices in the transverse, coronal and sagittal planes were displayed and the threshold was adjusted manually until the most satisfactory separation between the skin/fibroglandular tissue and the fat was obtained. To identify the voxels representing skin, the periphery of the breast was determined for each slice, and a morphological dilation operator was applied to dilate the periphery by an amount similar to the thickness of the skin (approximately 1.5 mm, Huang et al 2008). The voxels that were in the dilated periphery and also previously segmented in the fibroglandular class (which included the skin) were classified as skin voxels. Finally, a 3 × 3 integer median filter was applied to the classified slices. The segmentation reduced the noise in the image but also removed some detail in the parenchyma (see figure 2). The VBD was calculated as

| (1) |

where Vfg, Vad and Vsk are respectively the volumes of fibroglandular, adipose and skin tissues. We also computed the VBD excluding the skin as

| (2) |

Figure 2.

Illustration of segmentation on a coronal CT slice. Left: original slice in units of the effective linear attenuation coefficient (cm−1) displayed with a narrow window; right: segmented slice.

2.2. Deformation

2.2.1. General

A number of finite-element studies have been conducted to simulate the deformation of breast tissue to investigate the effect of material properties (Tanner et al 2006) and mechanical compression (Qiu et al 2004, Kellner et al 2007). These tools were used in our study to simulate the mechanical displacements that would occur under compression of the breast in mammography.

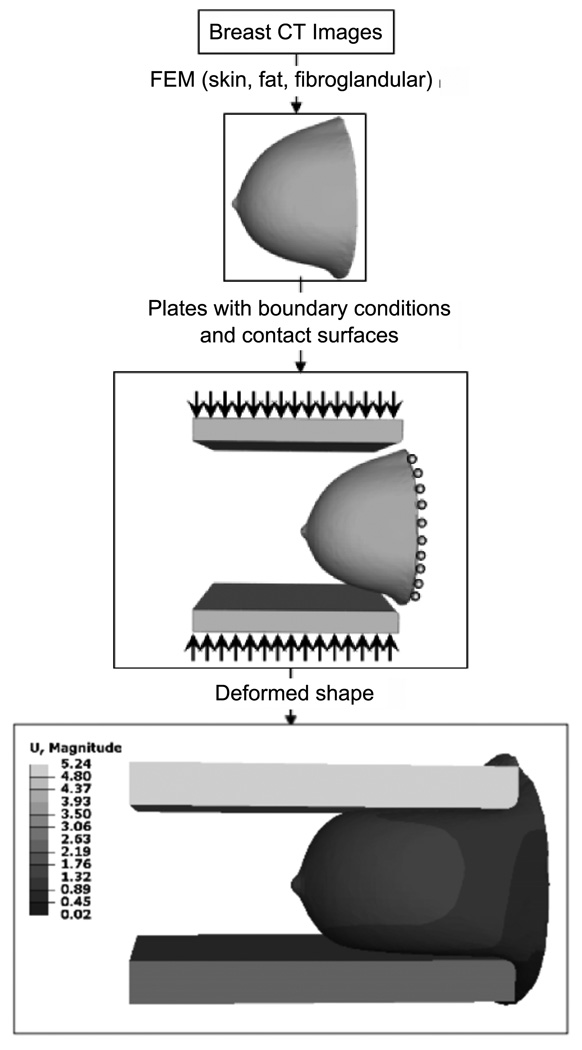

From the segmented data obtained from the CT images of the volunteers, 3D finite-element representations of the breast were constructed, and the linear elastic material properties (Kellner et al 2007) as listed in table 1 were attributed correspondingly to the skin, fat and fibroglandular tissue classes.

Table 1.

Elastic properties of breast tissue.

| Tissue | Modulus of elasticity (kPa) |

Poisson’s ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Fat | 1.0 | 0.49 |

| Fibroglandular | 10.0 | 0.49 |

| Skin | 88.0 | 0.49 |

To simulate the compression of the breast, the finite-element breast model is placed between two rigid plates with rounded corners (with 0.5 cm radius). The bottom plate is initially raised to an appropriate fixed position under the breast to provide support and the top plate moves downward to achieve the specified target thickness for the ‘compressed’ breast (see figure 3). The plates were offset toward the nipple (i.e. away from the chest wall) by approximately 2 cm to facilitate mechanical modeling of the compression. The target compression thickness was selected as a function of breast diameter at the chest wall using the relation determined by Boone et al (2005).

Figure 3.

Illustration of the finite-element model (FEM) deformation process. U represents the magnitude of the displacement in cm.

2.2.2. Boundary conditions

The surface of the breast at the chest wall plane (where it attaches to the thorax) is allowed to be displaced in the superior–inferior direction only. The breast is allowed to slide on the plates as compression is applied using a contact-surface model consisting of the external surface of the skin, and the surface of the plates facing the breast. A coefficient of friction of 0.1 is used to simulate the movement restriction of the breast in contact with plates. Similar values have been used by Pathmanathan et al (2008) and Yin et al (2004), but to the best of our knowledge, experimental coefficients of friction between the breast and compression plate are not available. Finally, in order to accommodate large deformation of the breast, nonlinear geometry is used in the analysis.

2.3. Mammogram simulation

The deformation algorithm produced a displacement vector for each point in the volume. These were used to displace the initial segmented CT volume m0(x, y, z), where m0 represents the tissue composition, initially having the two possibilities after segmentation of m0 = 1 for fibroglandular tissue and m0 = 0 for adipose tissue, to the new ‘destination’ points. These were then interpolated onto a regular Cartesian grid using a three-dimensional Gaussian kernel scaled to the appropriate voxel dimensions. The result was a displaced fractional density map m(x, y, z), which was converted into x-ray attenuation values μ using

| (3) |

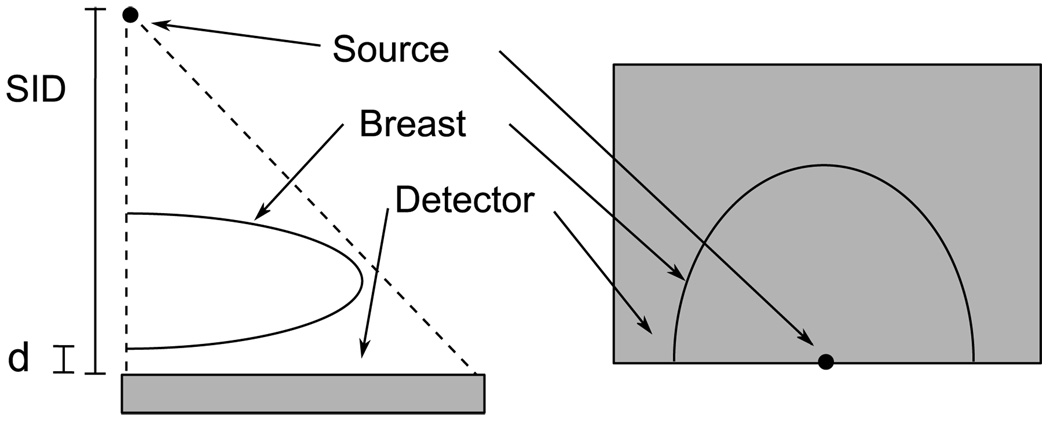

with μfg and μf the attenuation of fibroglandular and fatty tissue respectively, and E the x-ray energy. Note that the interpolation allows m to assume any value between 0 and 1. The attenuation values were obtained from Byng et al (1998) for breast equivalent plastic. A second interpolation was performed to displace the skin voxels only, which were then converted to attenuation values for skin, obtained from Hammerstein et al (1979) and then merged to complete the volume. The energies corresponded to a spectrum chosen as a function of the compression thickness (see table 2). A ray-tracing algorithm adapted from Siddon (1985) was then used to model the transmission of an obliquely incident x-ray beam through the volume, so that for each ray path, a product of attenuation coefficient and thickness, μ(E)T, at each energy, E, was obtained. The μ(E)T maps were then interpolated onto the simulated detector plane at a 0.25 mm detector element size. For this simulation, the lower surface of the breast was assumed to lie d = 10 mm above the detector plane (corresponding to the upper surface of the anti-scatter bucky), with a source to image distance (SID) of 660 mm. The source was located directly above the center of one edge of the detector, corresponding to the chest wall of the patient, as illustrated in figure 4. The thickness of the breast, T(x, y), was determined by projecting a volume of unity attenuation. The compression thickness of the breast was calculated as an average over the relatively flat portion of the thickness map.

Table 2.

Correspondence between the spectrum and breast thickness.

| Compression thickness (mm) |

kVp (Rh/Rh) | kVp (Mo/Rh) | kVp (Mo/Mo) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30–50 | 28 | 27 | 26 |

| 50–70 | 29 | 28 | 27 |

| 70–80 | 30 | 29 | 28 |

Figure 4.

Projection geometry. Left: side view; right, top view.

The relative signal due to the energy from directly transmitted (primary) x-rays, P(x, y), was calculated as

| (4) |

where η(E) = (1 − eμd(E)Td) · μden/μd is the fraction of x-ray photons absorbed in the detector medium of thickness Td and of linear attenuation, and linear absorption coefficients μd and μden, respectively. In this expression, Γ is the number of electron–hole pairs or scintillation photons generated per unit of absorbed x-ray energy and is assumed to be constant over the x-ray spectrum. The spectrum φ(E) was obtained from Boone et al (1997). The detector material used was CsI:Tl at a thickness of 120 µm, and the attenuation coefficients of the material were obtained from the NIST database (Hubbell and Seltzer 1996). The expression in the denominator is used to normalize the spectrum to unit area.

The relative signal due to scatter energy, S(x, y), was simulated by convolution, using the scatter point-spread function (PSF) data of Boone et al (Boone and Cooper 2000, Boone et al 2000). The functions were interpolated from the 1 cm thickness intervals and 50% fractional fibroglandular tissue composition intervals provided by Boone et al to 2 mm thickness intervals and 10% composition intervals, respectively. The scatter was calculated for the compression thickness, T, and average composition, m̄, of the breast and at each E. It was found that truncation of the scatter PSFs to a square region, 22 cm on a side, had a negligible effect on the scatter calculations:

| (5) |

where FOV(x, y) is defined as unity where the breast is present and zero elsewhere, SPSF(x, y) is the scatter point spread function in units of scattered energy per incident primary photon and T(x, y) is the thickness of the breast.

Because the value for the gain, Γ, is unknown, the relative signals obtained in equations (4) and (5) were scaled to the response of an actual detector (GE Senographe DS) by multiplying them by an experimental flat-field image I0(x, y), expressed in analog-to-digital units (ADU). It was acquired at the same kilovoltage (kVp) as used in the simulation of P and S, and divided by its mAs exposure. This procedure also automatically corrected for the remaining small variations in the image after the flat-fielding correction, and the effect of the inverse-square law.

We also included the effects of the anti-scatter grid and of detector glare. We used a method similar to Carton et al (2009) to measure the grid performance parameters. The point spread function due to detector glare, GPSF, was measured in a similar method to that used by Lutha and Rowlands (1990). It is obtained by measuring the signal at the center of a series of radio-opaque lead disks with different diameters. The GPSF was fitted to a relation GPSF = F1 · e−r/r1 + F2 · e−r/r2 where r is the distance from the center of a pixel of interest to a point (x, y) in the detector plane. The GPSF accounts for the low-frequency blurring of the detector. No correction for the high-frequency blurring was applied because the density is evaluated at a relatively coarse spatial scale.

Thus, the simulated mammogram I(x, y) in units of ADU is given by

| (6) |

where mAsI is the desired exposure, and Tp(T) and Ts(T) are respectively the primary and scatter transmission of the anti-scatter grid as a function of the average tissue thickness T. Since I0 is obtained in the detector plane, and S is expressed per incident primary photon, (i.e. at the entrance plane of the breast), it is necessary to scale I0 for the scatter portion of the image using the inverse-square law. Three sets of simulated mammograms were generated, for the Rh/Rh, Mo/Rh and Mo/Mo anode/filter combinations.

To test equation (6), images of slabs of tissue-equivalent plastic of 0% density and of dimensions 10 cm × 12.5 cm, with thicknesses of 3, 5 and 7 cm, were simulated at 26, 28, 30 and 32 kVp with a Rh/Rh anode/filter and compared with the corresponding experimental images. The differences in signal ΔI = Iexp − Isimu were observed, where Iexp and Isimu are the mean signal values of the phantom images for the experiment and simulation, respectively. ΔI was also converted to its corresponding difference in VBD, ΔM = ΔI · DIm. The sensitivity DIm was calculated as DIm = 100% · dm/dI, where I is the image pixel value at the center of a 12.5 × 10 × T cm3 parallelepiped calculated using equation (6), and with μ = μfg · m + μf · (1 − m) in equation (4).

2.4. Volumetric density measurement algorithm

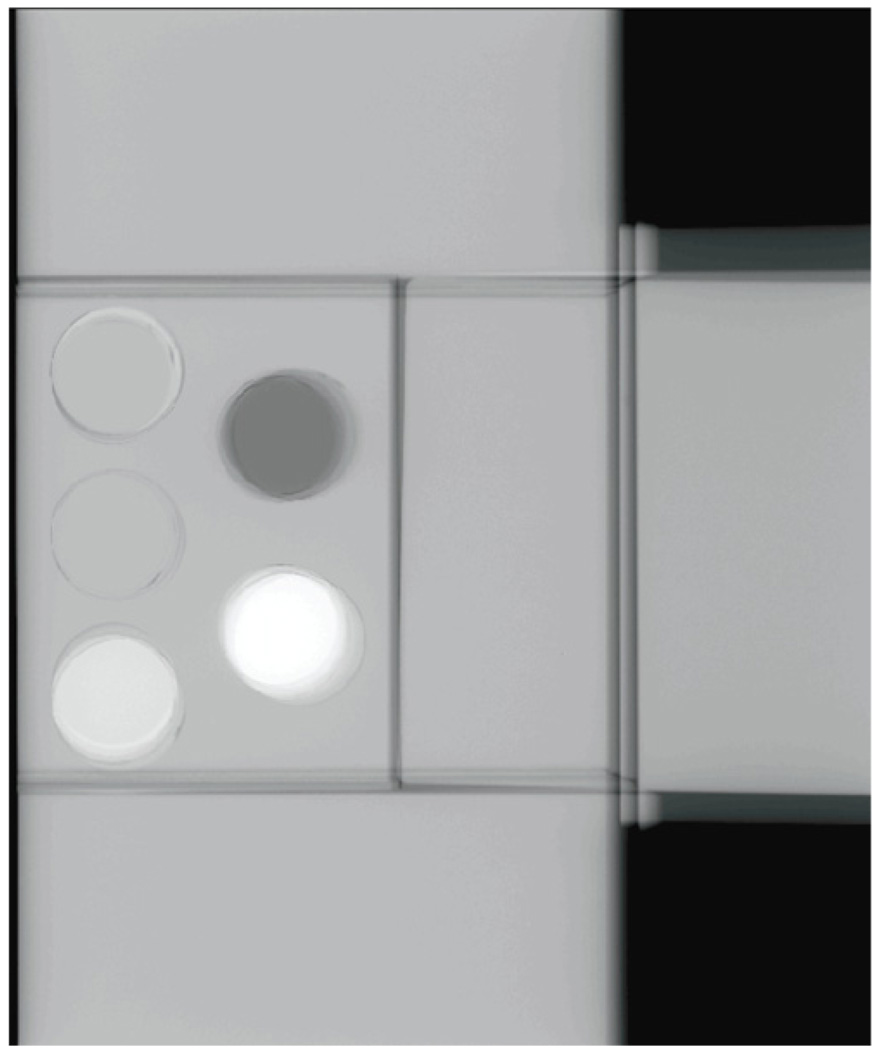

2.4.1. Calibration

An algorithm, Cumulus V, was developed for quantification of the VBD from mammograms as a refinement of the calibration method of Pawluczyk et al (2003). For a given target/filter combination, breast equivalent phantoms (by CIRS, Norfolk, VA, USA) of various thicknesses T containing cylindrical ‘plugs’ 2.54 cm in diameter, nominally equivalent to a breast fat and fibroglandular tissue mixture, are imaged at different kVp settings. To keep the contribution from scatter constant, the plugs are surrounded by regions composed of 50% adipose and 50% fibroglandular equivalent material of the same thickness as illustrated in figure 5. The images are first divided by the corresponding mAs exposure, and the detector signal values for fat, If(kVp, T), and fibroglandular, Ifg(kVp, T), are obtained as an average over the projected image of the disk. At the same kVp and anode/filter combinations, the signal I0(kVp) with no object in the field is obtained at the same locations as If and Ifg, and also divided by the mAs. The calibration is completed by computing two empirical relations: f0 for fat and f1 for fibroglandular tissue, obtained by fitting a two-dimensional second-degree polynomial surface to the signal values:

| (7) |

| (8) |

where aij and bij are the coefficients of a polynomial least-squares fit. The calibration procedure is repeated for the three target/filter combinations: Mo/Mo, Mo/Rh and Rh/Rh. We note that the attenuation coefficients of the tissue-equivalent plastic materials (Byng et al 1998) used for the calibration are slightly different than those of actual breast tissue (Johns and Yaffe 1987). For consistency we used the plastic attenuation values in the simulated mammograms described in section 2.3. The Cumulus V algorithm contains a correction, based on equation (6), to account for the difference in attenuation coefficients between the plastic and tissue.

Figure 5.

Sample image of the ‘plug’ phantom with surrounding ‘padding’.

2.4.2. Density measurement

With the image of a breast or phantom I(x, y) obtained at a given kVp and mAs, the oblique path length through the breast , where T(x, y), the thickness perpendicular to the x, y plane, is determined from the mammography system with appropriate corrections (Mawdsley et al 2009, Tyson et al 2009) and the values f0(kVp, T′), f1(kVp, T′) and are computed. The breast density m(x, y) for the path through tissue corresponding to each image pixel is determined by linear interpolation between the values f0 and f1, so that . Finally, the VBD is computed as , where Vc is the volume of the column of tissue above the pixel at the location (x, y). Vc is a truncated slanted pyramid, of volume Vc = (L/SID)2a2T · [1 − T/L + T2/3 · L2], where a is the pixel dimension and L = SID − d, with d = 10 mm the gap between the bottom of the object and the detector due to the bucky.

The density with no skin is also estimated by subtracting the ratio Vsk/VTOT from the VBD. The total volume is VTOT = ∑x,y Vc,while the volume of skin Vsk is approximated by assuming a 1.5 mm layer of skin around the breast (Huang et al 2008). Thus, Vsk = ∑x,y a2 · δ · 3 mm. The factor δ = 1.03 accounts for the approximately 3% higher attenuation of skin compared to pure fibroglandular tissue (Hammerstein et al 1979), at the mean energies used in mammography.

The precise thickness T(x, y) of the compressed breast in clinical mammography is not generally available. In Cumulus V, the method of Mawdsley et al (2009) and Tyson et al (2009) is used to predict the thickness of the breast at every point. However in this work, where the mammograms were simulated from CT, the thickness map T(x, y) of the breast was known exactly.

3. Results

3.1. CT analysis and deformation

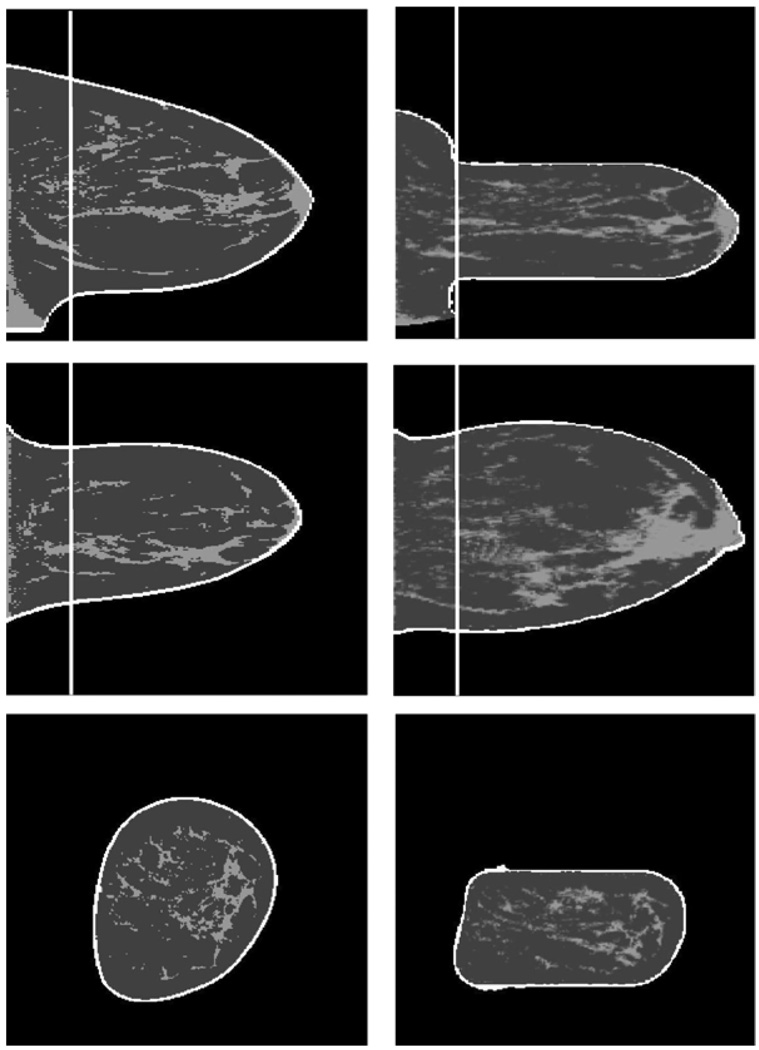

As a first test of the deformation procedure, we compared the volumes and VBD of the CT data (26 cases) and of the displaced volume. We found that the displacement conserved the total breast volume within an average of 1.5% of the original CT-derived value, whereas the VBD was conserved within 4.4%, on average, relative to the CT-derived absolute units of percent VBD (PVBD). The mechanical deformation procedure required offsetting the compression plates toward the nipple for the application of boundary conditions. This resulted in approximately 33% of the total breast volume, located in a region proximal to the chest wall not being fully compressed to constant thickness when the deformation was applied. For the purposes of validation of the Cumulus algorithm, the portion of the breast for which there was not uniform compression was cropped from the dataset and the remainder of the data were used for mammogram simulation. Therefore, the absolute volumes of the deformed and cropped breast and of its dense tissue in this comparison will be substantially lower than those in the entire breast. Figure 6 illustrates the deformation and cropping processes.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the finite-element deformation and cropping (white vertical line). Left: original segmented CT; right: displaced fractional density volume. From top to bottom, sagittal, transverse and coronal slices.

For the purposes of comparison with Cumulus V, the VBD determined by CT, VBDCT, was computed as the mean of the displaced fractional density volume m(x, y, z), within the cropped region. The total breast volume determined by CT, VCT, was also calculated on the deformed and cropped breast volume. The average VBDCT, VCT and compressed thickness of the 26 cases were 23.6%, 558 cm3 and 62 mm, respectively. The mean relative difference between VBDCT and the un-cropped original VBD from the CT image was 9%. The difference is explained by the presence of pectoralis muscle, segmented as fibroglandular tissue, often present near the chest wall, but removed by the cropping.

3.2. Mammogram simulation

Table 3 provides a summary of the results for the grid performance as a function of thickness, for all the beam configurations. Generally, our experimental uncertainties in Tp, the primary transmission, and Ts, the scatter transmission, were respectively ±0.01 and ±0.02.

Table 3.

Grid performance parameters

| anode/filter | Rh/Rh | Mo/Rh | Mo/Mo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kVp | 28 | 29 | 30 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

| Tp | 0 cm | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| 3 cm | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.64 | |

| 5 cm | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.66 | |

| 7 cm | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.69 | |

| Ts | 3 cm | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| 5 cm | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.15 | |

| 7 cm | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

In the characterization of glare, GPSF, under exposure conditions of 29 kVp and a Rh/Rh anode/filter, we measured F1 = 0.08, F2 = 0.03, r1 = 3.1 mm and r2 = 13.9 mm. We found no substantial difference in the parameters for the other exposure conditions.

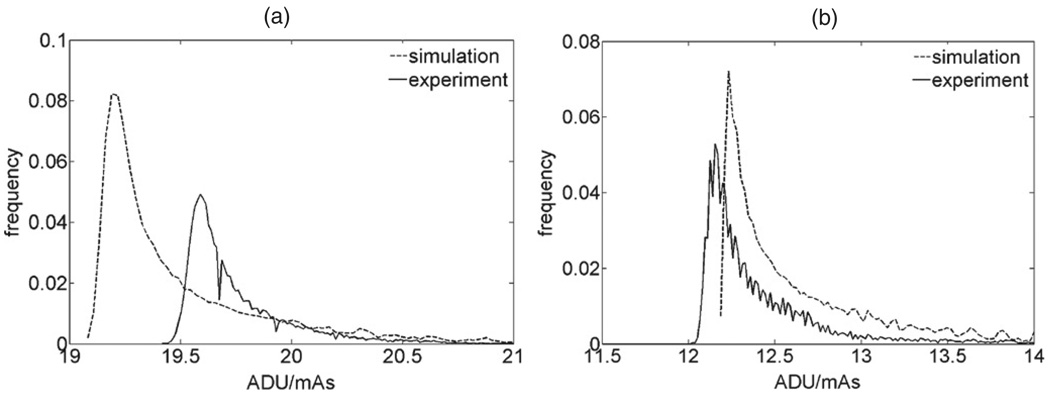

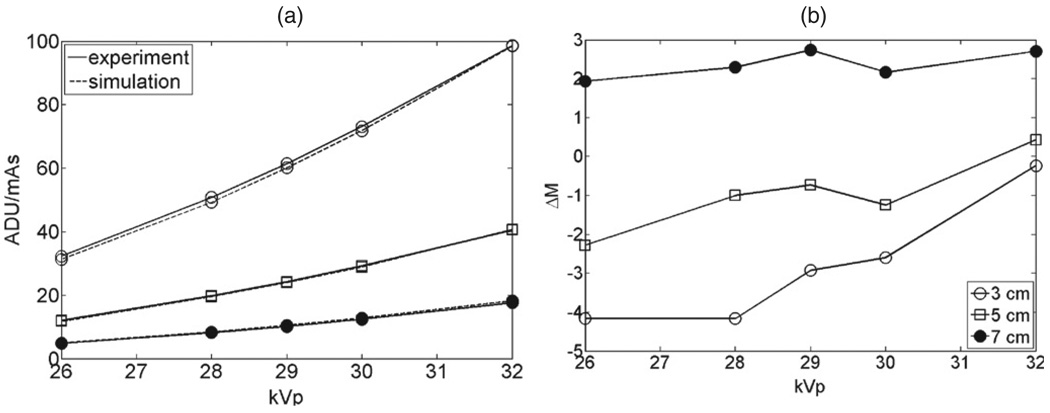

In the testing of the simulation versus experimental images of slabs, figure 7 shows the distribution of values (in ADU/mAs) in the simulated and experimental phantom images, for thickness 5 cm and 7 cm simulated and imaged at 28 kVp and 30 kVp respectively with a Rh/Rh anode/filter. The distributions were obtained over a central region of the phantom image, covering approximately 85% of the phantom’s projected surface. Figure 8(a) shows the comparison of the means of the distributions for all the thicknesses and kVp, and figure 8(b) the corresponding difference in density ΔM between the experiment and simulation. The sensitivity DIm in PVBD/(ADU/mAs) is shown in table 4.

Figure 7.

Distribution of ADU/mAs values on simulated and experimental images of a breast equivalent phantom of thickness 5 cm (a) and 7 cm (b), imaged at 28 kVp (a) and 30 kVp (b), with a Rh/Rh anode/filter. The dashed line is the simulated image and the solid line is the experimental image. The distributions are computed over an area of approximately 107 cm2 of the projected area of the phantom.

Figure 8.

(a) Comparison between the means of the experimental (full lines) and simulated (dashed lines) phantom images. The open circles, squares and disk represent the 3 cm, 5 cm and 7 cm images, respectively. Marker size is representative of the error in the values. (b) Corresponding difference ΔM in PVBD between experiment and simulation.

Table 4.

Sensitivity DIm in PVBD/(ADU/mAs).

| kVp | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (cm) | 26 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 32 |

| 3 | −4.07 | −2.73 | −2.30 | −1.97 | −1.50 |

| 5 | −7.61 | −4.81 | −4.00 | −3.38 | −2.48 |

| 7 | −15.01 | −9.15 | −7.48 | −6.23 | −4.50 |

The distributions of values between the experimental and simulated phantom images were remarkably similar. The root mean square (rms) rms(ΔI) was 0.72 ADU mAs−1, which corresponds to an rms error of 2.4% in the signal. Those errors in the signal resulted in a corresponding rms difference of 2.4 PVBD between the experiment and simulation.

3.3. Cumulus V

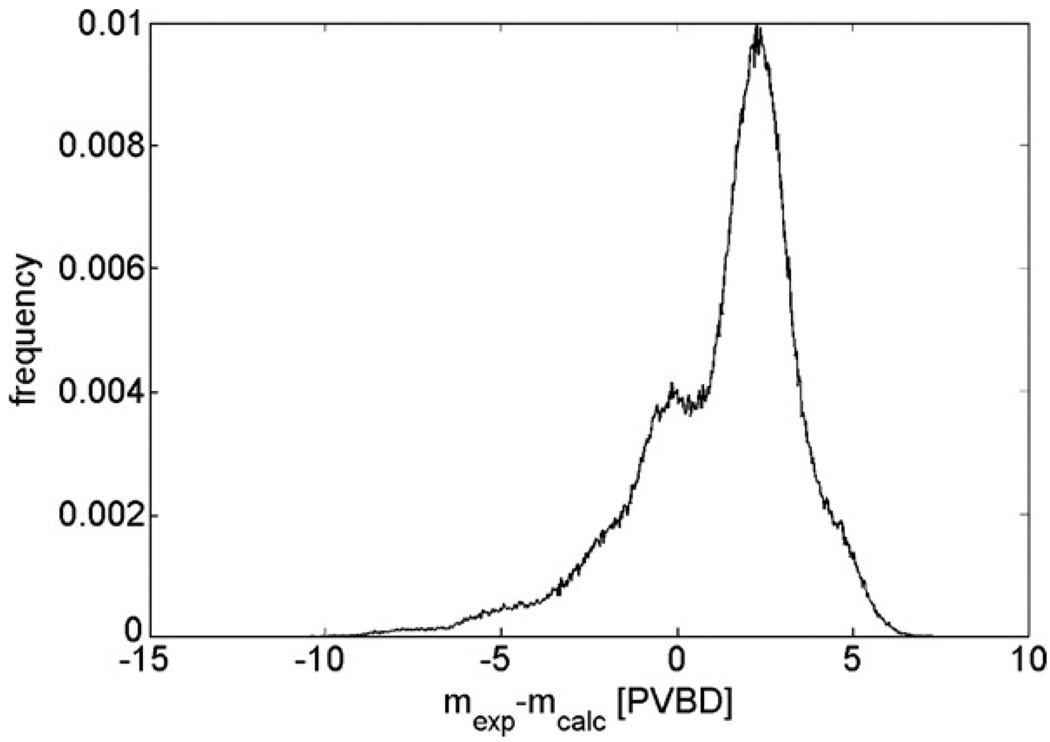

Cumulus was tested for self-consistency by analyzing images of the calibration phantoms (from a separate exposure), which also contain plugs of intermediate density (see figure 5). Figure 9 shows a histogram of the absolute density difference between the true density of the cylindrical plug (mexp) and the estimated density (mcalc), calculated at each pixel over the area of the plugs from phantoms of 3–8 cm thicknesses imaged at 26, 28, 30 and 32 kVp with a Rh/Rh target/filter. The mean difference mexp − mcalc was 1.25 PVBD with a standard deviation of 2.3 PVBD.

Figure 9.

Histogram of the VBD difference between the density on the plug phantoms and the calculated density from the phantoms using Cumulus.

3.4. Comparison of Cumulus with simulated mammograms

The 26 CT volumes were segmented, deformed, projected and used to simulate an image using equation (6). The values for the glare functions are found in section 3.2, and the values for Tp(T) and Ts(T) were linearly interpolated at the compressed thickness of the breast using the values of table 3. The images were then analyzed with Cumulus V to obtain the density VBDCV (with and without skin) and the total volume VCV. We restricted the computation of VCV and VBDCV to points where the computed VBDCV was in the physically acceptable range from 0% to 100%. On average, for the 26 cases simulated with an Rh/Rh anode/filter, only 6.4% of the total number of pixels in the breast image were excluded for this reason. These pixels corresponded to only 2.3% of the breast volume on average. For the Mo/Rh and Mo/Mo sets, these pixels corresponded to 1.9% of the breast volume. The likely cause of these nonphysical results is discussed in section 4.

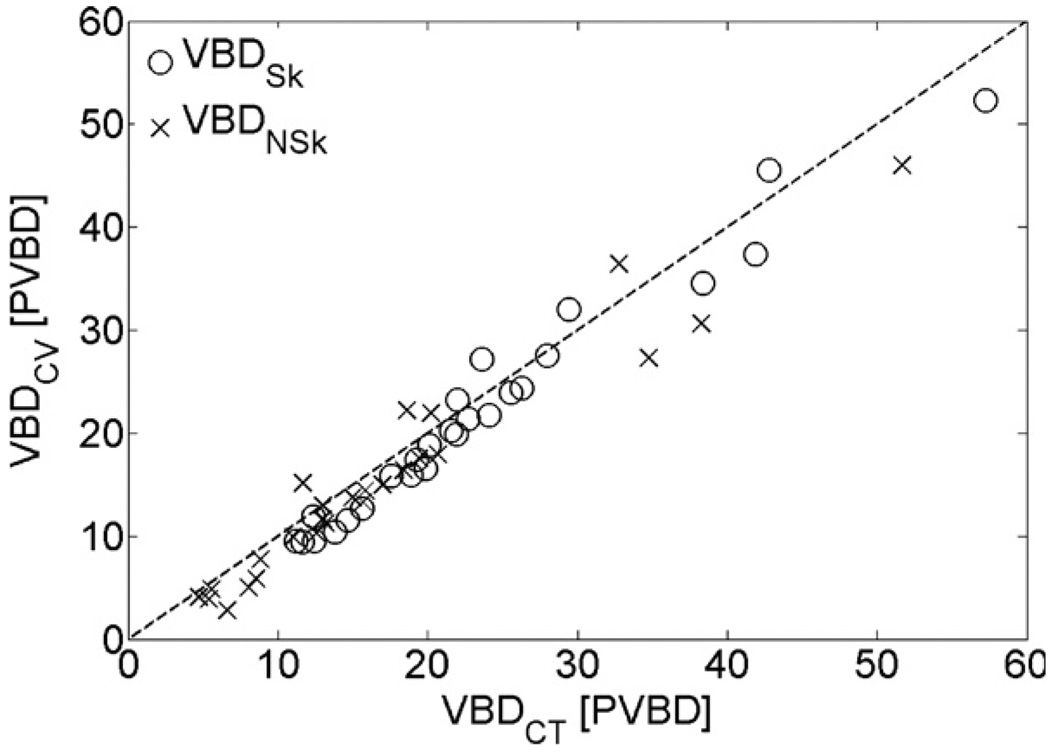

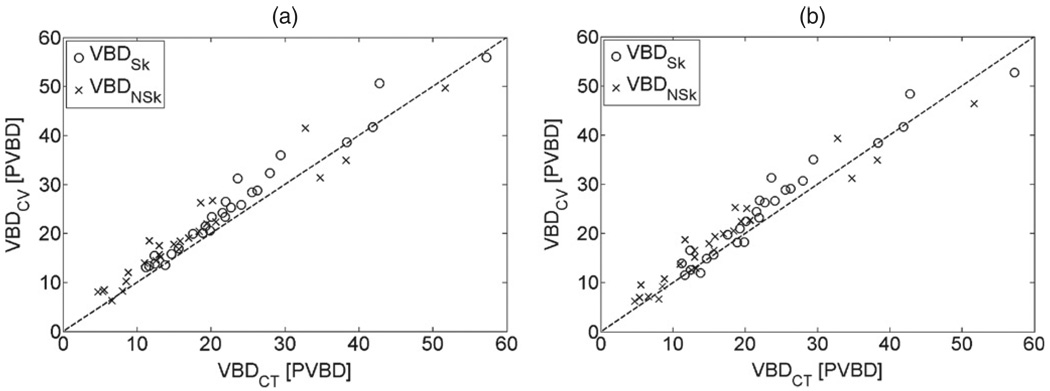

Excellent agreement between VCT and VCV was observed. A linear least-squares fit between the two gave a slope of 1.01 with an intercept of −7.2 cm3, and a correlation R2 = 0.999. The rms difference in volume between CT and Cumulus, rms(VCT − VCV), was 11.5 cm3 or 2.1% of the mean CT volume. Good agreement was observed between VBDCT and VBDCV, with and without the skin (see figures 10 and 11). Table 5 shows the results of linear regression analysis between VBDCT and VBDCV, and also the rms difference rms(ΔVBD), where ΔVBD = VBDCT − VBDCV.

Figure 10.

Comparison between VBD from CT and Cumulus V for the set of images with a Rh/Rh anode/filter combination. Open circles denote the VBD with skin and crosses the VBDNSk. Dashed line is the identity function.

Figure 11.

Comparison between VBD from CT and Cumulus V for the set of images with a Mo/Rh anode/filter (a) and a Mo/Mo anode/filter (b). Open circles denote the VBD with skin and crosses the VBDNSk. Dashed line is the identity function.

Table 5.

Linear regression and rms analysis between VBDCT and VBDCV

| Linear regression parameters |

Slope | Intercept (PVBD) |

R2 correlation | rms(Δ VBD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh/Rh | VBDSk | 0.992 | −1.4 | 0.963 | 2.6 |

| VBDNSk | 0.907 | 0 | 0.939 | 3.2 | |

| Mo/Rh | VBDSk | 1.002 | 2.4 | 0.960 | 2.6 |

| VBDNSk | 0.916 | 3.1 | 0.933 | 3.1 | |

| Mo/Mo | VBDSk | 0.970 | 2.5 | 0.942 | 2.5 |

| VBDNSk | 0.888 | 3.7 | 0.930 | 2.9 | |

4. Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the performance of an algorithm that measures the VBD from digital mammograms. We observed that our algorithm agrees very well with the values obtained from breast CT, both on the total volume of the breast and on the VBD with or without including the skin, as shown in figures 10 and 11. To the best of our knowledge, only the algorithm of Van Engeland et al (2006) also proposed a validation by means of comparison with a 3D dataset. Van Engeland et al (2006) used a simple polychromatic model of primary attenuation, without considering the effects of scatter or detector efficiency. Internal calibration was achieved by finding a reference fatty pixel value in the image. The validation was done by comparison with segmented MR images of the same 22 patients for which 4 digital mammographic views (2 for each breast) were obtained. The total breast volumes from the MR images and mammograms were not compared, but a correlation of 0.97 with a relative error of 13.6% was observed between the dense tissue fromMR and the average dense tissue from the four mammographic views of each patient.

Our algorithm is similar to those of Pawluczyk et al (2003) and Kaufhold et al (2002) in that it uses an empirical calibration of the detector signal as a function of thickness and composition from breast-equivalent phantoms to determine the density of a breast of known thickness, in which image was acquired under known conditions. The algorithm is susceptible to various sources of error. For the Rh/Rh anode/filter combination, the baseline error in the algorithm from a self-consistency test (section 3.3) results in a systematic underestimation of 1.25 ± 2.3 PVBD. This deviation is thought to originate from noise in the calibration images, errors due to the polynomial least-square fits and variations in the gain map between the time of calibration and the test. Thus, the offset of −1.4 PVBD and the rms difference of 2.6 PVBD between the ground truth from CT and the Cumulus algorithm discussed in section 3.4 suggest that the algorithm performs well when it is applied to the simulated breast images. It is also an indication that the model used to simulate the mammograms is accurate. The simulation model and baseline error in the algorithm were only tested versus phantom images for the Rh/Rh anode/filter combinations. However, the performance of Cumulus was similar on simulated images with Mo/Rh and Mo/Mo anode/filter combinations as it was with Rh/Rh.

Another type of error occurs when the algorithm yields a PVBD outside of the acceptable range between 0%and 100% (see section 3.3). There are several factors that may be responsible for this error. First is the use of calibration phantoms that have uniform thickness. Because the thickness of the breast varies and particularly because it decreases in the peripheral region, the scattered radiation profile will differ between the calibration exposures and actual mammograms. This can cause a discrepancy in the density determination. The points in the images that gave PVBD values less than 0 or greater than 100 had an average actual thickness of 18 mm and tended to be located mostly in the peripheral region. Moreover, the calibration curves converge to the same value at 0 thickness, and thus are close together for thin attenuators, causing the density estimation to be more sensitive to small errors in measuring or simulating the image signal at lower thickness.

Another reason for those unphysical results may arise from the assumption in the algorithm of a strictly two-compartment model for the breast. That is, the algorithm assumes that for a given tissue thickness and corresponding image signal, there is a unique combination of fat and fibroglandular tissue possible. Certainly, the presence of skin (and of blood vessels) in the breast is a departure from the two-compartment model, meaning that there is more than one combination of tissues possible that can give rise to a given signal at a given thickness. The skin has attenuation very close to that of fibroglandular tissue, and thus such errors are likely to occur only for pixels where the local density without the skin is already close to 100% or 0%, but it can occur at any thickness of tissue. We also note that the performance of Cumulus in estimating the VBDNSk was not as good as for VBDSk. This may be due to our assumption of a total skin thickness of 3 mm (1.5 mm × 2). In actuality, the skin thickness is likely to vary among women and possibly within the same breast.

The accuracy of the validation is also dependent on our model to simulate realistic digital mammograms. The model is based on a description of the physics of imaging the breast, considering the incident polychromatic x-ray spectrum, the primary and scattered radiation exiting the breast, the anti-scatter grid and the flat-panel detector conversion of x-ray energy into an image. It also employs experimental parameters, such as the grid transmission factors, the glare properties of the detector and a flood image to determine the gain of the detector as well as to account for the small variations in the field due to the heel effect. The performance of the model in simulating the image signal and VBD as a function of kVp and thickness is shown in figures 8(a) and (b). The errors varied approximately from −4 PVBD to 3 PVBD. We attribute the variation in error to two factors. First, although there can be a small dependence of the gain, Γ (equations (4) and (5)), on energy, this was not considered in our model. By assuming that Γ is constant, it is cancelled in equations (4) and (5), and the gain from the flood field image is assumed (equation (6)). This effect was small, and the average rms error in the signal between simulation and experiment was 2.4%. Secondly, we can see in table 4 that the sensitivity of density with respect to the image signal is larger for greater tissue thickness and for lower kVp. Thus, for some cases, small errors in the signal lead to noticeable errors in PVBD. The sensitivity was generally higher with the softer Mo/Rh or Mo/Mo anode/filter combination than that with the Rh/Rh combination. Thus, it is reasonable that a larger offset of approximately 2.5 PVBD was observed between VBDCT and VBDCV for the image sets using the Mo anode, compared with the −1.4 PVBD offset for the Rh anode image set.

We can analyze the errors associated both with the simulation and Cumulus in more detail by separating the image set (with the Rh/Rh anode/filter) into kVp subsets. Table 6 indicates the average ΔVBD = VBDCT − VBDCV and the predicted density error ΔM due to the model, linearly interpolated or extrapolated from the results of figure 8(b) at appropriate thickness. By combining ΔM with the systematic 1.25 PVBD underestimation shown in figure 9, we obtain a total expected difference between CT and Cumulus of −1.5 PVBD, 2.0 PVBD and 4.1 PVBD for the cases imaged at 28 kVp, 29 kVp and 30 kVp, respectively. The slight discrepancies between the expected VBD and the observed ΔVBD error within those sets may arise from the fact that the signal and VBD difference shown in figure 8(b) were obtained with phantoms of 0% density, while the simulated mammograms had average densities of 32%, 26% and 17%, for the subsets imaged at 28 kVp, 29 kVp and 30 kVp, respectively. This may have occurred because of an increase in the sensitivity, DIm, with increasing density and thus the errors due to our simulation model could be different for the cases studied than with the 0% phantoms. This is supported by the data in table 4 which show an increase in sensitivity with increased attenuation.

Table 6.

Observed (Δ VBD) and predicted (ΔM) VBD error as a function of kVp for the Rh/Rh image set

| kVp | 28 | 29 | 30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 3 | 14 | 9 |

| Mean T (cm) | 3.9 | 5.9 | 7.4 |

| Δ VBD (PVBD) | −3.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| ΔM | −2.7 | 0.8 | 2.9 |

Using actual mammograms with the corresponding CT from the same volunteers for purposes of validation will remove any errors due to the simulation of images. On the other hand, there are some advantages in using simulated mammograms. This approach allows for a self-consistent comparison between CT and the Cumulus algorithm. The validation is, therefore, insensitive to potential errors in the absolute anatomical VBD due to the segmentation or the finite-element deformation since they are preserved in the simulated projection mammogram. Furthermore, we compare a breast CT volume with its direct projection with no potential discrepancy (such as would be caused by inclusion of the chest wall with pectoralis muscle in the mammogram and not in the CT) between the two. And finally, the thickness of the breast is known exactly, and therefore potential errors due to errors in thickness measurement or estimation are avoided.

Area breast density is a well-validated risk factor for breast cancer risk. Methods such as the one proposed in this work will allow investigation of the relation between risk and VBD. Logically, one might expect VBD to be a better risk predictor than areal density because it presumably represents the amount of actual tissue at risk, the parenchyma and stroma. The VBD method can also be used to investigate the relation between volume and area density, by finding a global threshold in the volume density that results in an area density well correlated to a user-determined density.

Acknowledgments

We received valuable technical assistance and helpful advice from Dr James Mainprize. We are grateful for financial support through a Program Project grant from the Terry Fox Foundation.

References

- Boone JM, Alexander LC, Kwan J, Seibert A, Shah N, Karen KL, Nelson TR. Technique factors and their relationship to radiation dose in pendant geometry breast CT. Med. Phys. 2005;32:3767–3776. doi: 10.1118/1.2128126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone JM, Cooper VN., III Scatter/primary in mammography: Monte Carlo validation. Med. Phys. 2000;27:1818–1831. doi: 10.1118/1.1287052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone JM, Fewell TR, Jennings RJ. Molybdenum, rhodium, and tungsten anode spectral models using interpolating polynomials with application to mammography. Med. Phys. 1997;24:1863–1874. doi: 10.1118/1.598100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone JM, Kwan AL, Yang K, Burkett GW, Lindfors KK, Nelson TR. Computed tomography for imaging the breast. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 2006a;11:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s10911-006-9017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone JM, Lindfors KK, Cooper VN, III, Seibert JA. Scatter/primary in mammography: comprehensive results. Med. Phys. 2000;27:2408–2416. doi: 10.1118/1.1312812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone JM, Nelson TR, Kwan AL, Yang K. Computed tomography of the breast: design, fabrication, characterization, and initial clinical testing. Med. Phys. 2006;33:2185. [Google Scholar]

- Boone JM, Nelson TR, Lindfors KK, Seibert JA. Dedicated breast CT: radiation dose and image quality evaluation. Radiology. 2001;221:657–667. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2213010334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd NF, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:227–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byng JW, Mainprize JG, Yaffe MJ. X-ray characterization of breast phantom materials. Phys. Med. Biol. 1998;43:1367–1377. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/43/5/026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carton AK, Acciavatti R, Kuo J, Maidment AD. The effect of scatter and glare on image quality in contrast-enhanced breast imaging using an a-Si/CsI(TI) full-field flat panel detector. Med. Phys. 2009;36:920–928. doi: 10.1118/1.3077922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin PJ, Boyd NF. Mammographic parenchymal patterns and breast cancer risk: a critical appraisal of the evidence. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1988;127:1097–1108. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerstein GR, Miller DW, White DR, Masterson ME, Woodard HQ, Laughlin JS. Absorbed radiation dose in mammography. Radiology. 1979;130:485–491. doi: 10.1148/130.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine JJ, Malhotra P. Mammographic tissue, breast cancer risk, serial image analysis, and digital mammography: part 2. Serial breast tissue change and related temporal influences. Acad. Radiol. 2002;9:317–335. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine JJ, Malhotra P. Mammographic tissue, breast cancer risk, serial image analysis, and digital mammography: part 1. Tissue and related risk factors. Acad. Radiol. 2002a;9:298–316. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highnam R, Brady M, Shepstone B. A representation for mammographic image processing. Med. Image. Analysis. 1996;1:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)80002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highnam RP, Brady JM. Mammographic Image Analysis. Boston, MA: Kluwer; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SY, Boone JM, Yang K, Kwan AL, Packard NJ. The effect of skin thickness determined using breast CT on mammographic dosimetry. Med. Phys. 2008;35:1199–1206. doi: 10.1118/1.2841938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell JH, Seltzer SM. National Institute of Standard and Technology. 1996 http://physics.nist.gov/PhysRefData/XrayMassCoef/cover.html.

- Irwin ML, Aiello EJ, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, Gilliland FD, Baumgartner RN, Baumgartner KB, Ballard-Barbash R. Physical activity, body mass index, and mammographic density in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:1061–1066. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns PC, Yaffe MJ. Characterization of normal and neoplastic breast tissues. Phys. Med. Biol. 1987;32:675–695. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/32/6/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufhold J, Thomas JA, Eberhard JW, Galbo CE, Trotter DE. A calibration approach to glandular tissue composition estimation in digital mammography. Med. Phys. 2002;29:1867–1880. doi: 10.1118/1.1493215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellner AL, Nelson TR, Cerviño LI, Boone JM. Simulation of mechanical compression of breast tissue. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2007;54:1885–1891. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.893493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindfors KK, Boone JM, Nelson TR, Yang K, Kwan AL, Miller DF. Dedicated breast CT: initial clinical experience. Radiology. 2008;246:725–733. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2463070410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutha R, Rowlands JA. Origins of flare in x-ray image intensifiers. Med. Phys. 1990;17:913–921. doi: 10.1118/1.596447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawdsley GE, Tyson AH, Peressotti CL, Jong RA, Yaffe MJ. Accurate estimation of compressed breast thickness in mammography. Med. Phys. 2009;36:577–586. doi: 10.1118/1.3065068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathmanathan P, Gavaghan DJ, Whiteley JP, Chapman SJ, Brady JM. Predicting tumor location by modeling the deformation of the breast. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2008;55:2471–2480. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2008.925714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawluczyk O, Augustine BJ, Yaffe MJ, Rico D, Yang J, Mawdsley GE, Boyd NF. A volumetric method for estimation of breast density on digitized screen-film mammograms. Med. Phys. 2003;30:352–364. doi: 10.1118/1.1539038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftlas AF, Szklo M. Mammographic parenchymal patterns and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol. Rev. 1987;9:146–174. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala E, Warren R, McCann J, Duffy S, Day N, Luben R. Mammographic parenchymal patterns and mode of detection: implication for the breast cancer screening program. J. Med. Screen. 1998;5:207–212. doi: 10.1136/jms.5.4.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shephard JA, Kerlikowske KM, Smith-Bindman R, Genant HK, Cummings SR. Measurement of breast density with dual x-ray absorptiometry: feasibility. Radiology. 2002;223:554–557. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2232010482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddon RL. Fast calculation of the exact radiological path for a three-dimensional CT array. Med. Phys. 1985;12:252–255. doi: 10.1118/1.595715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata Y, Maskarinec G, Park SY, Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN. Mammographic density and dietary patterns: the multiethnic cohort. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2007;16:409–414. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000243852.05104.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner C, Schnabel JA, Hill DL, Hawkes DJ, Leach MO, Hose DR. Factors influencing the accuracy of biomechanical breast models. Med. Phys. 2006;33:1758–1769. doi: 10.1118/1.2198315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng M, Byrne C, Evers KA, Daly MB. Dietary intake and breast density in high-risk women: a cross-sectional study. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R72. doi: 10.1186/bcr1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson AH, Mawdsley GE, Yaffe MJ. Measurement of compressed breast thickness by optical stereoscopic photogrammetry. Med. Phys. 2009;36:569–576. doi: 10.1118/1.3065066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Engeland S, Snoeren PR, Huisman H, Boetes C, Karssemeijer N. Volumetric breast density estimation from full-field digital mammograms. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2006;25:273–282. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.862741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gils CH, Otten JD, Hendriks JH, Holland R, Straatman H, Verbeek AL. High mammographic breast density and its implications for the early detection of breast cancer. J. Med. Screen. 1999;6:200–204. doi: 10.1136/jms.6.4.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gils CH, Otten JD, Verbeek AL, Hendriks JH. Mammographic breast density and risk of breast cancer: masking bias or causality? Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1998;14:315–320. doi: 10.1023/a:1007423824675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead J, Carlile T, Kopecky KJ, Thompson DJ, Gilbert Fl, Jr, Present AJ, Threatt BA, Krook P, Hadaway E. Wolfe mammographic parenchymal patterns. A study of the masking hypothesis of Egan and Mosteller. Cancer. 1985;56:1280–1286. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850915)56:6<1280::aid-cncr2820560610>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe JN. Risk for breast cancer development determined by mammographic parenchymal pattern. Cancer. 1976;37:2486–2492. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197605)37:5<2486::aid-cncr2820370542>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe JN. Breast patterns as an index of risk of developing breast cancer. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1976a;126:1130–1137. doi: 10.2214/ajr.126.6.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MJ, Boone JM, Packard N, Alonzo-Proulx O, Huang SY, Peressotti CL, Al-Mayah A, Brock K. The myth of the 50–50 breast. Med. Phys. 2009;36:5437–5443. doi: 10.1118/1.3250863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Li L, Goldgof D, Sarkar S, Anton S, Clark RA. Three-dimensional finite element model for lesion correspondence in breast imaging. Proc. SPIE. 2004;5370:1372–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Yin HM, Sun LZ, Wang G, Yamada T, Wang J, Vannier MW. ImageParser: a tool for finite element generation from three-dimensional medical images. Biomed. Eng. Online. 2004;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]