Abstract

Objective:

Pre-college drinking has been shown to be a predictor of risky drinking and harmful outcomes in college. By contrast, less is known about how pre-college alcohol consequences influence subsequent consequences during the freshman year. The present study examined pre-college drinking and consequences in relationship to consequences experienced during the freshman year to better understand alcohol-related problems in this population.

Method:

Incoming freshmen (N = 340, 58% female) were randomly selected and completed measures of drinking quantity, alcohol-related consequences, and drinking style behaviors at pre-college baseline and at 10-month follow-up.

Results:

Pre-college consequences demonstrated a unique relationship with consequences at 10-month follow-up controlling for both pre-college and freshman-year alcohol consumption. Furthermore, pre-college consequences moderated the relationship between pre-college drinking and consequences at 10-month follow-up. For individuals who reported above-average pre-college consequences, no differences in 10-month follow-up consequences were observed across different levels of drinking. Finally, drinking style significantly mediated the relationship between the interaction between pre-college drinking and consequences and consequences at follow-up.

Conclusions:

The findings demonstrate the need to identify students who are at an increased risk of experiencing alcohol-related problems during their freshman year based on their history of consequences before college. Interventions aimed at these students may benefit from examining the usefulness of increasing protective behaviors as a method to reduce consequences in addition to reducing drinking quantity.

College student alcohol-related consequences continue to be a major public health concern. As college drinking has escalated, more intensive campus-based (Larimer and Cronce, 2002, 2007) and community-based (Hingson and Howland, 2002) interventions have been implemented. Although some have shown efficacy in reducing drinking (Larimer and Cronce, 2002, 2007), studies show that alcohol-related consequences as a whole have not decreased significantly in the past decade (Monitoring the Future, 1975–2006: Johnston et al., 2007). Furthermore, although some programs have reported reductions in alcohol-related consequences (e.g., Marlatt et al., 1998; Murphy et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2007), others have not (e.g., Borsari and Carey, 2000; Larimer et al., 2001; White, 2006). Considering the risk consequences pose to students themselves, as well as other individuals in the community, this discrepancy in outcomes warrants further attention.

The first year of college has been identified as a particularly high-risk transitional phase for increased heavy drinking and alcohol-related consequences. First, there are significant numbers of students who abstained from alcohol in high school but initiate drinking during their first year of college (Baer, 2002; Sher and Rutledge, 2007). Second, research has consistently identified increases in consumption and consequences during this period among individuals who initiate alcohol use before college (e.g., Baer et al., 1995; Hingson et al., 2002; Schulenberg and Maggs, 2002; Wechsler et al., 1998, 2002). From a prevention standpoint, the identification of predictors of alcohol-related consequences during this crucial developmental period would enable intervention efforts to be targeted to the highest risk individuals.

Although excessive drinking before college matriculation is a predictor of risky drinking during college (Mallett et al., 2010; O'Malley and Johnston, 2002; Schulenberg and Maggs, 2002), less is known about how alcohol-related consequences individuals experience before college influence the occurrence of subsequent consequences during the freshman year. Operant learning theory suggests the experience of alcohol-related consequences should serve as a deterrent for future consequences (Thyer et al., 2008). Thus, an inverse relationship between past and future consequences might be expected. However, although alcohol-related consequences are considered to be negative by public health officials and college administrators, students' evaluations of alcohol consequences vary considerably and can often be positive or neutral (Mallett et al., 2008). Based on these findings, it is also plausible to observe a positive relationship between past and future consequences.

The present research attempts to provide clarity on the relationships between pre-college drinking, pre-college consequences, and consequences experienced during the freshman year to identify students who are at the greatest risk during this high-risk transitional developmental period. First, the research examined the nature of the relationship between pre-college consequences and consequences experienced during the first year of college. Past research has primarily focused on the relationship between pre-college drinking and subsequent consequences experienced in the first year of college (e.g., Baer et al., 1995; Harford et al., 2002; Mallett et al., 2010). The current study provides an answer to the question of whether students who have a history of alcohol consequences before college are at an increased risk of experiencing more alcohol-related consequences during the first year of college. Second, the research examined whether consequences experienced before college account for unique variance in predicting consequences experienced during the freshman year over and above pre-college drinking. Research on college student drinking has indicated the association between drinking and consequences tends to be moderate, suggesting a considerable portion of variance is unexplained by alcohol consumption alone (Larimer et al., 2001, 2004; Turner et al., 2000). Although drinking is a necessary condition for experiencing alcohol-related consequences, the empirical data suggest that it is not a sufficient stand-alone predictor of alcohol problems. Thus, the analyses expand on studies that have examined the relationship between pre-college drinking and subsequent consequences only by focusing on pre-college consequences as a predictor. Third, the research examined whether pre-college consequences moderate the relationship between pre-college drinking and alcohol-related consequences experienced during the freshman year. Research has shown that college students who experience alcohol-related consequences (e.g., blackouts, regretted sexual encounters) felt they could consume more alcohol in the future before experiencing these same consequences again (Mallett et al., 2006). Based on these findings, students who have a history of experiencing more pre-college consequences may engage in more pre-college drinking and also experience more alcohol consequences in college. Thus, the current study answers the question about whether experiencing greater numbers of pre-college consequences strengthens the relationship between pre-college drinking and consequences during the freshman year.

A secondary focus of the study expands on the analyses of pre-college drinking, pre-college consequences, and consequences experienced during the freshman year by examining the style or manner in which students drink when they are in college as a mediator (e.g., drinking games, not pacing alcohol consumption, not setting limits). Based on the findings of Mallett et al. (2006), it was hypothesized that students who experience higher rates of pre-college consequences and pre-college drinking would engage in more risky drinking styles during the first semester as a freshman, which in turn would result in more consequences experienced during the freshman year. This answers the question of whether pre-college drinking and pre-college consequences influence college drinking style, which in turn will predict higher rates of consequences over the course of their freshman year.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 340 first-year college students who were recruited as part of a larger study before college matriculation (Turrisi et al., 2009). Participants were randomly selected from two large public northeastern and northwestern universities and were screened during the summer before the start of the fall semester. Inclusion criteria consisted of participating in club or team sports during high school, because research has shown individuals who participate in high school athletics are among those at highest risk for risky alcohol consumption in college (Dou-mas et al., 2006; Ford, 2007; Hildebrand et al., 2001; Martens et al., 2006; Turrisi et al., 2006). Eligible participants provided informed consent, completed an online screening assessment, and completed baseline survey before college matriculation. Of all participants who completed the screening assessment as part of the larger study, 79% of individuals met inclusion criteria (Turrisi et al., 2009). Participants included in the current study were randomly assigned to the control condition as part of the larger study. These individuals were examined to explore naturally occurring drinking patterns over the freshman year that were not influenced by an intervention.

Among the subsample examined in the current study, the mean age was 17.9 (SD = 0.39), with 58.2% identifying as female. The ethnic distribution was 80.2% White, 10% Asian/Asian American, 1.2% Black, 1.9% Hispanic/Latino, 3.8% multiracial, and 2.9% “other.” All procedures used in the study were approved by each university's institutional review board, and treatment of participants was in compliance with American Psychological Association ethical guidelines.

Procedure

As described by Turrisi et al. (2009), participants were randomly selected from the registrar's database of incoming first-year students. Invitation letters were sent to participants explaining the study, compensation incentives, and study procedures; the letters also contained a URL and a personal identification number for accessing the survey. Participants were informed that they would receive $ 10 for completing the initial screening survey, $25 for the baseline pre-college survey, and $30 for follow-up surveys. They also were to receive a $5 bonus for completion of any survey within 48 hours.

Two follow-up assessments were conducted during the fall and spring semesters (approximately 5 and 10 months after the pre-college baseline). The 10-month follow-up was selected to capture the freshman year of college. Individuals completed baseline in the summer before college matriculation and completed follow-up 10-months later at the end of the academic year. Participants received mail and email invitations, a survey URL, a unique personal identification number, and email reminders to access the survey. Survey completions yielded high retention at 10-month follow-up (n = 305; 89.7%). The original efficacy study (Turrisi et al., 2009) examined potential differences between completers and those who discontinued the study and found no significant differences on drinks per weekend and number of consequences reported at baseline (all ps > .05).

Measures

Alcohol-related consequences.

The 23-item Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White and Labouvie, 1989) was used to assess alcohol-related consequences at the pre-college baseline and 10-month follow-up. Participants indicated the number of times they experienced each consequence during the past 3 months on a 5-point scale, which ranged from never (0) to more than 10 times (4). The 23 items were summed and computed into a composite variable for each time period. The average consequences score at baseline was 2.93 (SD = 4.22) and at follow-up was 4.60 (SD = 6.10).

Alcohol use.

Study participants were asked to specify the number of drinks they consumed on each day of a typical week, using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985). Baseline survey responses for Friday and Saturday were summed, resulting in the total number of drinks consumed on a typical weekend. The average number of drinks participants reported consuming per weekend was 3.53 (SD = 5.35). A standard drink definition was included for all measures (i.e., 12 oz. of beer, 10 oz. of wine cooler, 4 oz. of wine, 1 oz. of 100-proof distilled spirits, or 1.25 oz. of 80-proof distilled spirits).

Drinking style behaviors.

Behaviors representing drinking style were drawn from the National College Health Assessment Survey (American College Health Association, 2000). Students were asked to indicate how often they engage in 14 protective behaviors when consuming alcohol with the following response options: I don't drink (1), always (2), usually (3), sometimes (4), rarely (5), and never (6). To assess risky drinking styles, we removed items that did not specifically map onto alcohol consumption behaviors (e.g., use a designated driver). We subjected the remaining items to an exploratory factor analysis, using criterion pattern matrix loadings greater than .7 and inter-item correlations of .5 or greater. Nine items met the established criteria for inclusion in the analyses. Example of drinking style items included pacing (e.g., “I pace my drinks to 1 or fewer per hour”), avoiding drinking games, and setting limits (e.g., “I determine, in advance, not to exceed a set number of drinks”). Items were summed to create a composite frequency score for drinking style behaviors (α = .97; M = 31.61, SD = 13.66). Individuals who endorsed higher scores on these items used fewer protective behaviors and engaged in a risky drinking style.

Statistical analyses

Regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between pre-college baseline weekend drinking, baseline consequences, and consequences at 10-month follow-up. RAPI scores at 10 months were regressed onto mean-centered baseline weekend drinking, mean-centered baseline RAPI summed scores, and the product term of the two. The product term was computed by multiplying baseline weekend drinking and baseline RAPI summed scores (Jaccard and Turrisi, 2003). An estimate of the moderator effect was determined by the regression coefficient for the product term. Main effects of pre-college drinking and consequences were assessed in analyses run without the product term in the model. To test for statistical significance, bootstrapped asymmetrical 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed using 2,000 samples in AMOS using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). If the CIs around the regression coefficient contained the value of zero, then the effect was considered not significantly different from zero and was nonsignificant. This method tends to be conservative against erroneous effects relative to traditional regression, because it makes no assumptions regarding underlying sampling distributions.

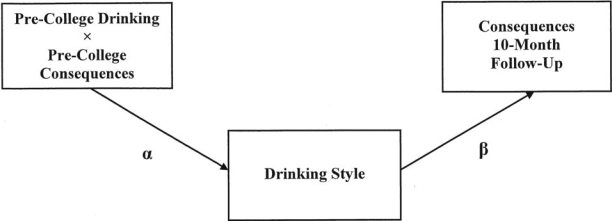

Mediation was assessed using the joint significance test of α (predictor to mediator path) and β (mediator to outcome path). MacKinnon and colleagues' (2002) examination of multiple mediation techniques revealed that the joint significance test was the most powerful and had the most conservative Type I error rates compared with other methods when using samples with ns < 1,000. Regression analyses using AMOS 18 in SPSS were used to test the α and β paths found in the model shown in Figure 1. The product of the α and β values (αβ) provides an estimate of the relative strength between the mediated effects (MacKinnon, 1994). When there is evidence for significant mediation (the α and β paths jointly show significance), 95% CIs around the αβ coefficient provide an estimate of the range of the effect (Shrout and Bolger, 2002). We used the same bootstrapping procedure discussed previously to derive the asymmetric CIs around the αβ coefficient.

Figure 1.

Drinking style as a mediator of the interaction of pre-college drinking and consequences and consequences experienced during the freshman year

Missing data for variables was less than 5%, which allowed for the use of the expectation-maximization algorithm method to impute missing data (Schafer and Graham, 2002).

Results

Descriptives

Despite all participants included in the sample being traditional first-year students younger than age 21, 36% reported consuming alcohol at pre-college baseline. At the 10-month follow-up, 60% of participants reported consuming alcohol. In addition, 37% of the students reported experiencing alcohol-related consequences at baseline, and 55% reported experiencing at least one consequence at 10-month follow-up.

Main effects analyses

Consistent with previous reports (Baer, 2002), a statistically significant relationship between baseline weekend drinking and consequences at 10-month follow-up was observed (b = 0.48, 95% CI [0.35, 0.64], p < .05). As baseline drinking increased, so did consequences at 10-month follow-up. Second, the relationship between pre-college baseline consequences and consequences at 10-month follow-up was assessed controlling for drinking at both baseline and at 10-month follow-up. This analysis revealed a significant relationship between baseline consequences and consequences at 10-month follow-up controlling for drinking (b = 0.71, 95% CI [0.56, 0.88], p < .05). Thus, the relationship between pre-college baseline consequences and consequences at 10-month follow-up was significant and independent of the effects of drinking.

Moderation analysis

The next focus of the analyses examined whether pre-college baseline consequences moderated the relationship between baseline drinking and consequences at 10-month follow-up. This analysis revealed a significant moderator effect (b = −0.04, 95% CI [-0.07, −0.01]). To examine the nature of the effect, mean differences in consequences at 10-month follow-up for pre-college baseline weekend drinking and baseline consequences were assessed using Tukey honestly significant difference post hoc tests. The critical difference used to assess significant differences was .88. Examination of the means (and standard errors) in Table 1 revealed significant mean differences between all levels of pre-college drinking for individuals who reported below-average pre-college baseline consequences (p < .05). As the amount of pre-college drinking increased, there was a significant increase in consequences at 10-month follow-up. The same pattern was observed for individuals who reported average pre-college baseline consequences. Significant mean differences were observed between all levels of pre-college drinking (p < .05). In contrast, for individuals who reported above-average pre-college baseline consequences, no differences in 10-month follow-up consequences were observed between any of the different levels of baseline drinking. As the amount of pre-college drinking increased, there was no significant increase in consequences at 10-month follow-up.

Table 1.

Mean Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index consequence scores reported at 10-month follow-up for participants across different levels of reported pre-college drinking and consequences

| Pre-college consequences |

|||

| Pre-college weekend drinking | Below average M(SE) | Average M(SE) | Above average M(SE) |

| Above average | 5.862 (0.608) | 6.532 (0.540) | 10.257 (0.590) |

| Average | 4.239 (0.319) | 5.165 (0.324) | 10.309 (0.868) |

| Below average | 2.617 (0.426) | 3.798 (0.475) | 10.360(1.279) |

Notes: Mean differences greater than 0.88 are significantly different, p < .05.

Mediation analysis

The third focus of the study examined mediation (see Figure 1). Because the high-order moderator effect was significant in the previous analyses, our analyses examined drinking style as a mediator in the relationship between the moderator (the interaction between pre-college baseline drinking and baseline consequences) and consequences at 10-month follow-up. The analyses revealed that the α path (the relationship between the moderator and drinking style) was significant (b = −0.14, 95% CI [-0.19, −0.10], p < .05). The more pronounced the moderator effect (more pre-college consequences leading to more consequences at follow-up at all levels of drinking), the more individuals engaged in risky drinking styles (e.g., drinking games, not pacing drinking). Second, the analyses revealed the β path (the relationship between drinking styles and consequences at 10-month follow-up) was also significant (b = 0.18, 95% CI [0.15, 0.21], p < .05). The more individuals engaged in risky drinking styles, the more consequences were reported at 10-month follow-up. Finally, the joint product path (αβ) was also significant (b = −0.03, 95% CI [-0.04, −0.02], p < .05), suggesting that drinking styles mediated the relationship between the moderator effect and consequences at 10-month follow-up. Higher rates of pre-college consequences resulted in experiencing more consequences across all levels of drinking as a function of engaging in risky drinking styles during the first year of college.

Discussion

Higher education across the nation has been shifting toward implementing large-scale universal intervention approaches to all incoming freshmen. These programs often incorporate an assessment of drinking-related behaviors, yet little is known about the optimal way to intervene with students based on their pre-college alcohol-related consequences. The current study aimed to address this gap in the literature by examining consequences experienced before college as a unique predictor of freshman-year consequences. In addition, pre-college consequences were examined as a moderator of pre-college drinking and consequences experienced during the freshman year of college. Furthermore, drinking style was examined as a mediator to identify variables in addition to quantity of alcohol that both contribute to the experience of consequences and can be targeted for behavioral change. Identifying key predictors of alcohol-related harm experienced during the freshman year would enable universities to better identify high-risk incoming freshmen and provide appropriate intervention efforts.

The first goal of the study was to examine the unique influence of pre-college consequences on consequences experienced during the freshman year, independent of alcohol consumption. The findings indicated pre-college consequences significantly predicted consequences at 10-month follow-up. Furthermore, although pre-college alcohol consumption was a significant predictor of consequences experienced during the freshman year, our findings revealed that pre-college consequences account for unique variance in consequences observed at 10-month follow-up over and above drinking alone. This suggests that targeting reductions in drinking alone may not be sufficient in reducing alcohol-related consequences among students who are at the highest risk of experiencing them.

The second goal of the study was to examine pre-college consequences as a moderator of pre-college drinking and consequences reported at 10-month follow-up. Findings from the moderator analyses revealed that students who experienced higher rates of consequences before college matriculation experienced significantly more consequences during their freshman year, regardless of the amount of alcohol they consumed. For individuals who reported the highest rates of pre-college consequences, those who consumed lower amounts of alcohol before college were at the same high risk of experiencing consequences as heavy drinkers. In addition, students who experienced above-average rates of pre-college consequences experienced an average of twice the number of consequences by the end of their freshman year, compared with those who reported fewer baseline consequences (Table 1). It is interesting to note that individuals who experienced the highest rate of consequences before college experienced the most consequences during college, which is in contrast with operant learning theory. These individuals may not perceive alcohol consequences as completely aversive, and thus the reinforcing aspects of alcohol consumption may outweigh the negative aspects, which may be perpetuating their risky drinking patterns. It is also important to note that the individuals with a high rate of pre-college consequences who consumed lower amounts of alcohol may have been consuming less alcohol to avoid consequences; however, their motivation for alcohol consumption was not assessed. Future studies would benefit from examining these motivations to better understand the reinforcing relationship between alcohol consumption and consequences. Furthermore, this finding demonstrates the need to identify variables that uniquely predict consequences in order to enhance intervention efforts, considering that lighter drinking did not translate into fewer consequences among this subgroup.

The third goal of the study used mediation analyses to examine drinking style as a potential explanation of why individuals who experience more pre-college consequences have an increased risk of consequences during the freshman year. Considering that pre-college drinking quantity was not a sufficient predictor of experiencing consequences during the freshman year for those who experienced high rates of pre-college consequences, the manner in which these individuals drank may provide insight. We found support for a mediation model indicating higher rates of pre-college consequences resulted in experiencing more consequences across all levels of drinking as a function of engaging in risky drinking styles. Results from the mediation analyses highlight the importance of increasing protective behaviors (e.g., pacing drinks, avoiding drinking games, setting limits for consumption) as a method to reducing consequences, in addition to reducing drinking quantity.

Implications

Findings from the study have important and relevant implications for intervention efforts targeting incoming college freshmen. Results demonstrate the need to identify students who are at an increased risk of experiencing alcohol-related problems during their freshman year based on their history of consequences before college. Students who engage in heavy drinking before college matriculation are often identified as high risk; however, screening students on alcohol consumption alone may miss those individuals who experience consequences without consuming excessive amounts of alcohol. These individuals are at an increased risk of experiencing more consequences during their freshman year and would benefit from intervention efforts. Interventions aimed at these students may benefit from including more than just a message that centers around consuming less alcohol. Brief motivational interventions involving multiple components (e.g., BASICS [Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students]; Dimeff et al., 1999) have shown efficacy with higher risk students (Larimer et al., 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998), which may be the result of aspects of the intervention that address protective and risk behaviors related to consequences, as well as drinking quantity. Little is known about the impact and efficacy of the specific components of these intervention approaches, and the current study highlights the need for further exploration and identification of key variables that can be enhanced and/or incorporated into existing intervention efforts to increase their impact on student outcomes.

Limitations and future directions

Although the study highlights the importance of assessing students' history of consequences in relationship to reducing risk for future consequences, it is not able to identify long-term and more chronic consequences that may develop throughout college (e.g., academic problems, dependence symptoms). Etiological work is needed to address these long-term outcomes, as well as to examine patterns of risk among individual consequences. In addition, future studies would benefit from identifying a threshold consequence score to accurately assess high-risk individuals based on the number and types of consequences experienced before college matriculation. This information could be used to identify students who would benefit from receiving appropriate intervention efforts when they arrive on campus. It would be useful for researchers to identify more variables that account for variance in experiencing consequences and use them to inform intervention efforts. Finally, it is important to note that, although two campuses were included in the study, results may not generalize to all college students. Also, the data were self-reported; therefore, possible biases should be considered. To promote honest responding, participants were reminded of their confidentiality numerous times throughout the survey, as well as in the consent form, and were informed they could skip any question they felt uncomfortable answering.

Conclusions

The first year of college has been identified as a high-risk transitional period for increased alcohol-related consequences. The present research examined the relationships between pre-college drinking, pre-college consequences, and consequences experienced during the freshman year. Research also examined whether pre-college drinking and pre-college consequences were related to subsequent drinking style in college and higher rates of consequences during their freshman year. The analyses were conducted to answer questions about whether reducing drinking alone is sufficient to reducing consequences in first-year college students. The findings of the present study highlight the importance of taking into consideration pre-college consequences in prevention efforts and demonstrate the need to focus on other variables in addition to alcohol consumption to reduce the risk of experiencing consequences among those with a history of problems.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01 AA 12529.

References

- American College Health Association. National college health assessment 2000 user's manual. Linthicum, MD: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. High-risk drinking across the transition from high school to college. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Turrisi R, Wright DA. Risk factors for heavy drinking in college freshmen: Athletic status and adult attachment. The Sport Psychologist. 2006;20:419–434. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JA. Alcohol use among college students: A comparison of athletes and nonathletes. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:1367–1377. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Wechsler H, Muthén BO. The impact of current residence and high school drinking on alcohol problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:271–279. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand K, Johnson DJ, Bogle K. Comparison of patterns of alcohol use between high school and college athletes and non-athletes. College Student Journal. 2001;35:358–365. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Zakocs RC, Kopstein A, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:136–144. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Howland J. Comprehensive community interventions to promote health: Implications for college-age drinking problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:226–240. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Turrisi R. Interaction effects in multiple regression. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2006: Vol. II. College students and adults ages 19–45 (NIH Publication No. 07–6206) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention and treatment: A review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:148–163. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, Cronce JM. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Analysis of mediating variables in prevention and intervention research. In: Cázares A, Beatty LA, editors. Scientific methods for prevention intervention research. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1994. –153.pp. 127 NIDA Research Monograph 139, DHHS Publication No. 94–3631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Bachrach RL, Turrisi R. Are all negative consequences truly negative? Assessing variations among college students' perceptions of alcohol related consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Lee CM, Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Turrisi R. Do we learn from our mistakes? An examination of the impact of negative alcohol-related consequences on college students' drinking patterns and perceptions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:269–276. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Ray AE, Turrisi R, Belden C, Bachrach RL, Larimer ME. Age of drinking onset as a moderator of the efficacy of parent-based, brief motivational, and combined intervention approaches to reduce drinking and consequences among college students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1154–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Dams-O'Connor K, Beck NC. A systematic review of college student-athlete drinking: Prevalence rates, sport-related factors, and interventions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Benson TA, Vuchinich RE, Deskins MM, Eakin D, Flood AM, Torrealday O. A comparison of personalized feedback for college student drinkers delivered with and without a motivational interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:200–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Supplement 14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonex-perimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyer BA, Sowers KM, Dulmus CN. Comprehensive handbook of social work and social welfare: Vol. 2. Human behavior in the social environment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Turner AP, Larimer ME, Sarason IG. Family risk factors for alcohol-related consequences and poor adjustment in fraternity and sorority members: Exploring the role of parent-child conflict. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:818–826. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Larimer ME, Mallett KA, Kilmer JR, Ray AE, Mastro-leo NR, Montoya H. A randomized clinical trial evaluating a combined alcohol intervention for high-risk college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:555–567. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Mallett KA, Mastroleo NR, Larimer ME. Heavy drinking in college students: Who is at risk and what is being done about it? Journal of General Psychology. 2006;133:401–420. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.401-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Changes in binge drinking and related problems among American college students between 1993 and 1997. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 1998;47:57–68. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR. Reduction of alcohol-related harm on United States college campuses: The use of personal feedback interventions. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2006;17:310–319. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Capone C, Laforge R, Erickson DJ, Brand NH. Brief motivational intervention and alcohol expectancy challenge with heavy drinking college students: A randomized factorial study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2509–2528. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]