Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess whether the effect of parenthood on alcohol intake varies according to the context in which the drinking act occurs.

Method

The data were drawn from the Canadian Addiction Survey, a national telephone survey conducted in 2004. The analytical sample included 1,079 drinking occasions nested in 498 female drinkers and 926 drinking occasions nested in 403 male drinkers between 18 and 55 years of age. A multilevel linear statistical model was used to estimate the variance related to the drinking occasion (Level 1) and to the parental role (Level 2).

Results

Parenthood was not associated with alcohol intake per occasion. Drinking context variables brought great explanatory power to the study of alcohol intake, but, overall, the effect of parenthood on alcohol intake did not vary according to the context in which drinking occurs. Only one interaction between the parental role and contextual characteristics was found.

Conclusions

Men's and women's alcohol intake within drinking contexts is more likely to be influenced by the immediate context in which drinking occurs than by their parental role. The explanation for alcohol behaviors within the general Canadian population may lie as much in the situation as in the person.

Numerous studies have described the association between the parental role and alcohol use (for a review, see Leonard and Eiden, 2007). Although trends have been observed, the part of variance in alcohol use that is explained by the parental role is generally small within the general population (Hajema and Knibbe, 1998). A reason for this finding could be that many empirical studies have ignored the context in which people drink when estimating the influence of the parental role on alcohol intake. In fact, no research has hitherto examined whether the association between parenthood and drinking behaviors is invariant across situations. The aim of this study was to assess whether the influence of parenthood on alcohol intake varies according to the context in which the drinking act occurs.

Among social roles, the parental role is the one whose relationship with alcohol behaviors is the least documented. Thus far, the results of the few studies on this topic show that men and women who become parents tend to decrease their overall alcohol use (Labouvie, 1996), their weekly frequency of drinking six units or more on one occasion (Hajema and Knibbe, 1998), and their work-related drinking (Shore, 1997). Among American men and women 35 years of age, parents who live with children are less likely than either nonparents or noncustodial parents to report having consumed five or more drinks in one sitting at least once in the past 2 weeks (Merline et al., 2004). Studies using both male (Paradis et al., 1999) and female samples (Cho and Crittenden, 2006) have indicated that being a parent is associated with lower drinking levels.

According to Cho and Crittenden (2006), mothers are also less likely than nonmothers to experience drinking problems. Recent studies have shown that parenthood has a greater influence on drinking in women than in men. For example, Kuntsche et al. (2006) found that, specifically for women, being a parent is associated with a decreased risk of drinking more than 20 grams of pure ethanol a day. According to Leonard and Eiden's review (2007) on the influences of family transition on alcohol consumption, being a parent is associated with a decrease in the frequency of drinking and excessive drinking for men and women alike, and the effect is strongest close to the transition from being childless to becoming a parent.

Most sociological studies on the relationship between parenthood and alcohol consumption tend to refer to the opportunity perspective that was introduced to the alcohol field by Knibbe et al. (1987), who brought to light different pathways through which the parental role may influence alcohol consumption. This perspective contends that, because of the tasks and responsibilities associated with child care, parents may find it difficult to allocate time and resources to drinking (Ahlstrom et al., 2001; Bloomfield et al., 2006; Gmel et al., 2000; Hajema and Knibbe, 1998; Holmila et Raitasalo, 2005; Knibbe et al., 1987; Kuntsche et al., 2006; Wilsnack et al., 2000). Parents may also avoid drinking situations with characteristics conducive to increased drinking that is likely to interfere with acting out parenthood (Paradis, 2010). All in all, the perspective posits that “the more [a person's] life is structured by meaningful activities that others expect one to engage in … the less likely he or she is to engage in heavy-volume drinking or risky single occasion drinking” (Kuntsche et al., 2009, p. 1264).

However, within sociology, some argue that the study of social conduct should focus on what's going on (Cohen, 1996; Elster, 2007; Goffman, 1966). Pragmatists insist that rational social actors select and analyze conditions on the basis of which they order their actions. Social conducts often are no more than an impulse of relevance, a requirement of the immediate situation (de Fornel and Quéré, 2000; Joas, 1997). As Elster puts it, “a behavior is often no more stable than the situations that shape it” (Elster, 2007, p. 185). Hence, a limitation of the alcohol studies cited above is their focus on overall drinking patterns and the implicit presumption that, because of different lifestyles, parents and nonparents will drink differently. Such studies neglect the fact that, regardless of lifestyle, drinking situations are not invariant among individuals. Individuals drink in a variety of situations that are normatively marked and that influence alcohol consumption accordingly (Kairouz and Greenfield, 2007). As Harford (1978) points out, “the consumption of alcoholic beverages is situationally specific, rather than a trans-situational property of specific individuals” (p. 289). Through different studies, a group of researchers has shown that a great deal of the variability in alcohol intake is the product of contextual influences (Demers et al., 2002; Kairouz et al., 2002; Kairouz and Greenfield, 2007). Hence, the predictive value of individual characteristics may be situationally dependent.

That the drinking act is grounded in specific situations is well documented. Research has brought to light the fact that alcohol is consumed under a combination of locational, relational, circumstantial, and temporal conditions (Demers, 1997; Harford, 1979; Harford and Gaines, 1982; Harford et al., 1976, 1983; Simpura, 1991). For example, the probability of heavy drinking is generally higher in places such as bars, discos, or taverns than in a restaurant or at home (Clapp et al., 2006; Cosper et al., 1987; Single and Wort-ley, 1993; Snow and Landrum, 1986). Other studies have shown that drinking in multiple locations in the course of an evening is associated with increased alcohol consumption (Hughes et al., 2008; Pedersen and Labrie, 2007).

Among university students, some found heavy drinking to be most likely to occur in pubs, bars, nightclubs, and residential halls (Kypri et al., 2007; Paschall and Saltz, 2007), but others found it most likely to occur in private homes (Demers et al., 2002). Individuals' drinking behaviors are also indissociable from individuals' drinking companions (Demers, 1997; Orcutt, 1991). Although university students consume more alcohol per occasion with larger groups (Demers et al., 2002), studies on drinking in licensed establishments (Hennessy and Saltz, 1993; Sykes et al., 1993) have shown that the larger the group, the more alcohol is consumed. However, these studies also show that mixed-gender groups tend to have a moderation effect on the consumption. Special circumstances such as parties, weddings, and social gatherings imply heavier drinking than everyday life contexts such as having a meal (Simpura, 1983, 1987; Single and Wortley, 1993). In terms of temporal characteristics, drinking during weekends is usually associated with heavier intake than drinking during the week (Demers, 1997; Demers et al., 2002a). All in all, studies point to drinking contexts having a rather robust influence on individuals' alcohol intake per occasion.

From our perspective, examining the occasions in which drinking occurs could shed light on a pathway in which being a parent structures alcohol intake. The enactment of a role is dynamic, and one implication of this fact is that the characteristics of a situation may determine the extent to which a role becomes “active” (Bates, 1956; Goffman, 1961). Although previous alcohol studies have focused on the relationship between parenthood and overall drinking measures, it remains unverified whether parenthood also shapes alcohol use on specific occasions, namely, on occasions when the drinking norms facilitate heavy drinking—that is, a drinking style that is incompatible with parenthood. In these situations, the effect of the parental role should be significant, because well-adapted individuals will not allow “their participation in short-term situations which offer immediate satisfaction to interfere with an adequate performance of their … role” (Knibbe et al., 1987, p. 464). Conversely, in situations that promote light/moderate drinking, such as a meal at a restaurant, the parental role should not matter, given that light/moderate drinking is not likely to interfere with acting out parenthood.

The extent to which being a parent relates to alcohol consumption in heavy drinking contexts could be greater for women. As Correll and colleagues (2007) report, there is a contemporary cultural belief that mothers should always be “on call” for their children. Hence, it may be less acceptable for mothers than for fathers to fulfill a desire to “fit in” in an immediate situation and to drink according to the specific context in which alcohol consumption occurs. Even within the current pluricultural and multiethnic Canadian society, where Canadians exhibit considerable heterogeneity in their behaviors, mothers in general may still be more cautious than fathers about letting their participation in short-term situations interfere with their parental role.

To broaden our understanding of the association between the parental role and alcohol consumption, this study explored one possible pathway in which parenthood may influence drinking—that is, whether the effect of parenthood on alcohol intake varies according to the context in which drinking occurs. To our knowledge, this moderator effect model of contexts has not been tested before. Ultimately, the main hypothesis of this research was that significant differences between parents' and nonparents' alcohol intake will arise when drinking occurs in a context that is normatively associated with heavy drinking.

Method

Data source

Data were derived from the Canadian Addiction Survey 2004 (CAS), a collaborative initiative sponsored by Health Canada, the Canadian Executive Council on Addictions, and three provinces to gauge Canadians' attitudes toward, beliefs about, and personal use of alcohol and other drugs. A two-stage sampling design was used. First, within each of the 21 strata defined by Statistics Canada's Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) versus non-CMA areas within each province, a random sample of telephone numbers was selected with equal probability. Then, within selected households with more than one eligible adult, one member of the household who could complete the interview in English or French was selected according to the most recent birthday of all household members. Interviews were conducted using computer-assisted telephone interviewing from December 16 to December 23, 2003, and from January 9 to April 19, 2004. To maximize the response rate, at least 12 call attempts were made to unanswered numbers, and all households in which people refused to participate on the first attempt were contacted again.

The response rate was 43% of all eligible households. Although this rate is low, it is similar to that of other popu-lational health surveys, and it reflects the general trend that the response rate for large-scale studies has been declining throughout the developed world (Curtin et al., 2005; Rogers, 2006). The weighted CAS distribution compares favorably to the census data, although the CAS sample tends to over-represent respondents who were married and had a university degree. Such differences are common in telephone surveys (Trewin and Lee, 1988). The median interview time was 23 minutes. Specific details on the research design and methods can be found in the CAS detailed report (Adlaf et al., 2005) and the Canadian Addiction Survey 2004: Microdata eGuide (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2007).

The CAS, a representative sample of the Canadian population, consisted of 13,909 respondents (8,188 females and 5,721 males) age 15 and older from all 10 provinces. However, to increase participation and reduce survey time, a three-panel design was implemented. Each respondent was randomly assigned to one of three panels, and each panel focused on specific items of interest in the CAS. Items about drinking occasions were asked of 40% of the respondents within the third panel (n =x 1,872). These respondents were invited to provide information for up to three drinking occasions, defined as the three most recent occasions over the past 12 months. For our study, only individuals who reported alcohol consumption at least once during the last 12 months and who were between 18 and 55 years of age were considered (n =x 1,026). After excluding cases with missing data, 901 drinkers and 2,005 drinking occasions remained in the analyses (on average, 2.2 occasions per drinker). The final sample was composed of 1,079 drinking occasions nested in 498 female drinkers and 926 drinking occasions nested in 403 male drinkers.

Measures

Dependent variable.

The outcome variable was the alcohol intake per occasion. Respondents were asked to think back to the last three occasions on which they drank alcohol over the past 12 months, and, for each of the occasions, they were asked: “How many drinks did you have?” This variable was logarithmically transformed to correct for the skewed distribution.

Contextual variables (Level 1).

The drinking situation encompassed five contextual characteristics. For each drinking occasion, respondents were asked to specify the following: the circumstance under which drinking occurred (a party, a get-together, a daily life circumstance, another circumstance), the location where the drinking took place (respondent's home, someone else's home, a restaurant, a bar/disco/nightclub), the group size (alone, dyad, 3–5 people, 6–10 people, >10 people), whether drinking occurred during the weekend, and whether it was during a meal.

Individual variables (Level 2).

The independent variable is the parental role. Respondents were asked: “How many children under 18 years are dependent on you for their well-being and welfare, regardless of whether they live with you?” To determine whether parents lived with their child, we also observed respondents' answers to two other questions: “Including yourself, how many people are currently living in your household?” and “What is your current marital status?” On the basis of these three questions, we were able to create a dummy variable that differentiated respondents who have at least one child younger than 18 years old living at home (0) from those who do not (1).

Analyses were controlled for age as a continuous variable ranging from 18 to 55. To control for socioeconomic status, analyses included educational level, an ordinal variable with seven possible responses ranging from (1) less than a high school degree to (7) university graduate studies. Moreover, given the known protective effect of marriage on alcohol use, analyses also controlled for marital status, a dummy variable that distinguished respondents who are married/are a common-law spouse (0) from those who are not (1).

Statistical analyses

The goal of our analyses was to examine whether an additive or a conditional relationship exists between the parental role and drinking occasions to explain women's and men's alcohol intake. Given the hierarchical structure of our data where drinking occasions (Level 1) were nested within individuals (Level 2), a multilevel linear regression model was used to estimate the variance deriving from the drinking occasion and the individual and to assess the manner in which contextual characteristics and parenthood influence alcohol intake (Bryk and Raudenbush, 1992; Goldstein, 1986; Goldstein and McDonald, 1988; Hox and Kreft, 1994). Analyses were controlled for age, marital status, and educational level.

Parameter estimation was done with iterative generalized least square (IGLS) (Goldstein, 2002; Goldstein and Ras-bash, 1992) using MLn 2.02 software (Rasbash et al., 2004). IGLS views the likelihood function as depending on random coefficients and fixed regression coefficients; the latter are treated as known quantities when computing the random parameters. Fixed coefficients were tested with normal deviate two-tailed significance reported atp < .05. Wald tests were used to assess statistical significance of categorical variables. For variance parameters, likelihood ratio tests were applied, and halvedp values were used (Snijders and Bosker, 1999). The proportion of variance explained for both Level 1 and Level 2 variables was calculated using Sniijders and Bosker formulas (Snijders and Bosker, 1994).

Regression models were fitted for the alcohol intake per occasion. Model 1 included no independent variables to estimate the distribution of the variance between contextual (Level 1) and individual variables (Level 2). Model 2 added the parental role variable. The three control variables were then added to Model 3. Model 4 was a full conditional model including both individual (Level 2) and contextual (Level 1) variables. This model allowed us to evaluate the extent to which drinking context and individual variables acted as additive factors to alcohol intake. Then, to specifically test the moderation hypothesis, two-way interactions between parenthood and contextual characteristic were tested one by one. Thus, the last model included the main effects of the variables and the significant interactions with the parental role variable.

Before performing multilevel analyses, bivariate analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between parenthood and the other study variables for women and men separately. For continuous and categorical variables, statistical significance was assessed with independent sample t tests and chi-square analyses, respectively.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Women.

Women's individual characteristics are presented in Table 1. Women who had at least one child at home did not differentiate themselves from women who did not with regard to age and education, but mothers were significantly more likely than nonmothers to have a spouse (72.6% vs. 56.3%). Regarding drinking occasions, our data indicated that women who had at least one child at home consumed alcohol within similar drinking contexts to those of women without children at home. Indeed, comparing the last three drinking occasions of Canadian women, the only significant difference was that mothers were significantly less likely to report drinking during the weekdays than nonmothers (28.0% vs. 38.3%). However, the data indicated that, overall, within their last three drinking occasions, women who had at least one child at home drank significantly less than women who were not living with a child at home (2.8 vs. 3.2 drinks).

Table 1.

Individual and contextual descriptions by parental role for women and men separately

| Women |

Men |

|||||

| Variable | Parents | Non-parents | Stat. signif. | Parents | Non-parents | Stat. signif. |

| Contextual characteristics | (n = 453) | (n = 626) | (n = 294) | (n = 632) | ||

| Circumstance, % | ||||||

| Party | 22.1 | 24.1 | 16.7 | 22.2 | ||

| Get-together | 42.6 | 42.0 | 36.1 | 40.5 | ||

| Daily-life circumstance | 22.5 | 24.3 | 34.0 | 25.5 | ** | |

| Other circumstance | 12.8 | 9.6 | 12.3 | 11.0 | ||

| With a meal, % (vs. w/o a meal) | 68.7 | 72.7 | 67.7 | 60.6 | * | |

| Weekdays,% (vs. Friday—Saturday) | 28.0 | 38.3 | *** | 41.2 | 37.0 | |

| Location, % | ||||||

| Home | 40.0 | 37.2 | 49.0 | 35.4 | *** | |

| Someone else's home | 28.5 | 29.6 | 23.8 | 31.3 | * | |

| Restaurant | 15.7 | 13.9 | 13.3 | 12.7 | ||

| Bar/disco/nightclub | 15.9 | 19.3 | 13.9 | 20.6 | * | |

| No. of drinking partners, % | ||||||

| None | 9.7 | 9.6 | 11.6 | 13.8 | ||

| 1 partner | 15.0 | 15.5 | 19.4 | 11.1 | *** | |

| 2–4 partners | 28.5 | 28.3 | 27.9 | 29.0 | ||

| 5–9 partners | 22.1 | 23.6 | 24.1 | 26.9 | ||

| ≥10 partners | 24.7 | 23.0 | 17.0 | 19.3 | ||

| Alcohol intake, M (SD) | 2.8 (2.0) | 3.2 (2.6) | *** | 3.4 (2.8) | 4.3 (4.6) | *** |

| Individual characteristics | (n = 212) | (n = 286) | (n = 132) | (n = 271) | ||

| Married/common law spouse, % (vs. not) | 72.6 | 56.3 | *** | 87.1 | 43.2 | *** |

| Age, M (SD) | 36.1 (7.7) | 37.3 (12.3) | 38.8 (7.5) | 35.5(12.1) | *** | |

| Education level, M (SD) | 3.75(1.8) | 3.9(1.9) | 3.8(1.9) | 3.6(1.9) | ||

Notes: Stat. signif. = statistical significance; w/o = without.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001.

Men.

Interestingly, fathers and nonfathers were quite different with regard to both their individual characteristics and the drinking contexts in which they consumed alcohol. Men who had a child at home were about twice as likely as those who did not to be married (87.1 % vs. 43.2%) and were significantly older (38.8 vs. 35.5 years old). With regard to their last three drinking occasions, fathers were significantly more likely than nonfathers to drink in a daily-life circumstance (34.0% vs. 25.5%), with a meal (67.7% vs. 60.6%), at home (49.0% vs. 35.4%), and in a dyad (19.4% vs. 11.1%). Fathers were also significantly less likely than nonfathers to have drunk at someone else's home (23.8% vs. 31.3%) and at a bar/disco/ nightclub (13.9% vs. 20.6%). Overall, on their last drinking occasions, fathers reported a smaller alcohol intake than men without children at home (3.4 drinks vs. 4.3 drinks).

Multilevel regression analyses

Women.

Women's results in the multilevel analyses are presented in Table 2. Women's null model (Model 1) indicated an overall mean alcohol intake per occasion (log) of 0.844, that is, 2.3 drinks per occasion in the original unit, and found sizable variance for both contextual and individual characteristics. The interclass correlation showed that 60.3% [0.290 / (0.290 + 0.191)] of the variance was at the individual level (Level 2), whereas 39.7% was at the contextual level (Level 1).

Table 2.

Multilevel linear regression for women's alcohol intake per occasion (logarithmic transformation)

| Variable | Null model param. | Indiv.-level model param. | Indiv.-level control model param. | Full main effects model param. |

| Constant | 0.844*** | 0.809*** | 1.538*** | 0.692*** |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Circumstance | ||||

| Party | 0.338*** | |||

| A get-together | 0.182*** | |||

| Daily-life circumstances | Ref. | |||

| Other circumstances | 0.030 | |||

| Meal | ||||

| During a meal | Ref. | |||

| Not during a meal | 0.083* | |||

| Moment | ||||

| Weekend | 0.145*** | |||

| Weekdays | Ref. | |||

| Location | ||||

| Your home | 0.126* | |||

| Someone else's home | 0.118* | |||

| Restaurant | Ref. | |||

| Bar/disco/nightclub | 0.263*** | |||

| Group size | ||||

| Alone | −0.019 | |||

| Dyad | Ref. | |||

| 3–5 people | 0.060 | |||

| 6–10 people | 0.210** | |||

| >10 people | 0.274*** | |||

| Marital role | ||||

| Not married | 0.129* | 0.112* | ||

| Married | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Level 2 | ||||

| Age | −0.017*** | −0.010*** | ||

| Education level | −0.041** | −0.026* | ||

| Parental role | ||||

| Nonparent | 0.061 | 0.064 | 0.064 | |

| Parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Random part | ||||

| σ2ε, Level 1 | 0.191 | 0.191 | 0.191 | 0.162 |

| σ2μ, Level 2 | 0.290 | 0.288 | 0.237 | 0.195 |

| Statistics | ||||

| -2-log likelihood | 1,974.374 | 1,973.227 | 1,902.975 | 1,715.687 |

| χ2 | 1.147 | 71.399 | 258.687 | |

| df | 1 | 4 | 16 | |

| P | .2842 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| R2 of Level 1 variables | 0.4% | 11% | 26% | |

| R2 of Level 2 variables | 1% | 14% | 29% | |

Notes: Indiv. = individual; param. = parameter; ref. = reference.

p ≤.05;

p ≤.01;

p ≤ .001.

The effect of parenthood was estimated in the second model, leaving parents as the reference category. The results showed that being a mother was not a significant predictor of alcohol intake per occasion. In the third model, age, education, and marital status were added to the equation. Although the effect of parenthood remained nonsignificant, results showed that, as women's age and education increased, alcohol intake decreased. Being married was also negatively associated with alcohol intake. Control variables significantly added to the prediction of women's alcohol intake per occasion, χ2(4) = 71.399, p ≤ .0001. Together, individual variables explained 11% of the variance between occasions and 14% of the variance between women.

In the fourth model, all contextual variables were added to the analyses. The circumstance, moment, location, and group size were significantly related to alcohol intake per occasion, but whether drinking occurred during a meal was not. Together, contextual variables significantly added to the prediction of women's alcohol intake per occasion, χ2(12) = 187.288, p ≤ .0001). Women drank more during a party (B = 0.338) and a get-together (B = 0.182) (as opposed to a daily-life circumstance); on Friday or Saturday (B = 0.145) (as opposed to other days of the week); in a bar/disco/nightclub (B = 0.263), at home (B = 0.126), and at someone else's home (B = 0.118) (as opposed to at a restaurant); and in a large-size (B = 0.274) or a medium-size (B = 0.210) group (as opposed to in a dyad). With the inclusion of contextual variables, the parental role remained nonsignificant. This model accounted for 26% of the variance between occasions and 29% of the variance between women.

Finally, the extent to which women's parental role interacted with contextual variables was tested. No significant interactions were found; therefore, none is reported here. However, it should be mentioned that the parental role and location interaction nearly attained statistical significance, χ2(3) = 6.033, p = . 11.

Men.

Men's results in the multilevel analyses are presented in Table 3. Men's overall alcohol intake per occasion was 2.9 drinks per occasion (i.e., log value = 1.054). The interclass correlation showed that 61.3% of the variance was situated at the individual level, whereas 38.7% was situated at the contextual level. Hence, as much for men as for women, nearly two thirds of the variance in alcohol intake was owing to the individual, whereas more than one third was owing to the drinking occasion.

Table 3.

Multilevel linear regression for men's alcohol intake per occasion (logarithmic transformation)

| Final main effects and interactions model |

||||||

| Variable | Null model param. | Indiv.-level model param. | Indiv.-level control model param. | Full main effects model param. | Main effects param. | Interaction x Parental Roleparam. |

| Constant | 1.054*** | 0.952*** | 1.812*** | 0.916*** | 0.860*** | |

| Level 1 | ||||||

| Circumstance | ||||||

| Party | 0.495*** | 0.404*** | 0.110 | |||

| A get-together | 0.316*** | 0.475*** | −0.233* | |||

| Daily-life circumstances | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Other circumstances | 0.320*** | 0.354** | −0.051 | |||

| Meal | ||||||

| During a meal | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Not during a meal | −0.078 | −0.080 | ||||

| Moment | ||||||

| Weekend | 0.185*** | 0.179*** | ||||

| Weekdays | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Location | ||||||

| Your home | 0.207** | 0.206** | ||||

| Someone else's home | 0.056 | 0.060 | ||||

| Restaurant | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Bar/disco/nightclub | 0.278*** | 0.275*** | ||||

| Group size | ||||||

| Alone | −0.174* | −0.177* | ||||

| Dyad | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| 3–5 people | 0.068 | 0.069 | ||||

| 6–10 people | 0.190* | 0.186* | ||||

| >10 people | 0.353*** | 0.344*** | ||||

| Marital role | ||||||

| Not married | 0.030 | 0.035 | 0.042 | |||

| Married | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Level 2 | ||||||

| Age | −0.016*** | −0.009** | −0.009** | |||

| Education level | −0.065*** | −0.053** | −0.052** | |||

| Parental role | ||||||

| Nonparent | 0.150* | 0.075 | 0.056 | 0.129 | ||

| Parent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Random part | ||||||

| σ2ε, Level 1 | 0.247 | 0.387 | 0.248 | 0.192 | 0.190 | |

| σ2μ, Level 2 | 0.391 | 0.247 | 0.332 | 0.309 | 0.305 | |

| Statistics | ||||||

| -2-log likelihood | 1,933.295 | 1,929.403 | 1,886.806 | 1,704.353 | 1,694.545 | |

| χ2 | 3.892 | 46.489 | 228.942 | 238.750 | ||

| df | 1 | 4 | 16 | 19 | ||

| P | <.05 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||

| R2 of Level 1 variables | 1% | 9% | 21% | 22% | ||

| R2 of Level 2 variables | 1% | 12% | 21% | 22% | ||

Notes: Indiv. = individual; param. = parameter; ref. = reference.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001.

Based on the second model, men's parental role was a significant predictor of alcohol intake per occasion. Compared with fathers, nonfathers reported more alcohol intake (B = 0.150). However, when control variables were added to the third model, the parental role became nonsignificant. In addition, men's marital status was not related to alcohol intake per occasion, but, as age and education increased, alcohol consumption per occasion significantly decreased. Control variables improved the fit of the previous model, χ2(4) = 46.489, p ≤ .0001. Together, individual variables explained 9% of the variance between occasions and 12% of the variance between individuals.

Contextual variables were added to the analyses in the fourth model. The parental role remained nonsignificant, but the prediction of men's alcohol intake was significantly improved, χ2(12) = 182.453, p ≤ .0001. With the exception of whether drinking occurred during a meal, every contextual variable was related to men's alcohol intake per occasion. Men reported greater alcohol intake during a party (B = 0.495), at a get-together (B = 0.316), or under any other circumstances (B = 0.320) than in a daily-life circumstance. When drinking occured on Friday or Saturday (B = 0.185), alcohol intake was greater than if drinking occured on any other day. Men drank more in a bar/disco/nightclub (B = 0.278) and at home (B = 0.207) than at a restaurant. Finally, men drank more in a large group (B = 0.353) or in a medium-size group (B = 0.190) than they did in a dyad but less when they drank alone (B = −0.174). This full model accounted for 21% of the variance between occasions and 21% of the variance between individuals.

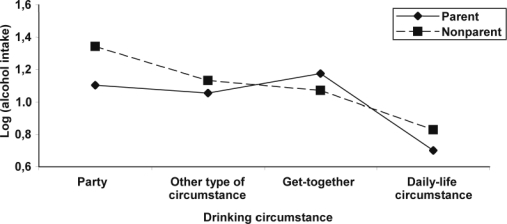

Finally, the possibility that men's parental role interacted with contextual variables was tested. Interactions were first tested separately, and all significant effects were kept. From this final model, one interaction was found and is presented in Figure 1. The circumstance in which drinking occurs was a significant moderator of parenthood on alcohol intake among men. Indeed, although fathers and nonfathers did not report statistically different alcohol intake when drinking occured in a party, a daily-life circumstance, or another type of circumstance, at a get-together fathers consumed significantly more alcohol than nonfathers, BParenthood × Get-Together = −0.233, χ2(3) = 9.862, p = .02. It should be added that the parental role and group size interaction was just about significant, χ2(4) = 7.05 1, p = .13.

Figure 1.

Men's predicted alcohol intake by parental role and drinking circumstances

Discussion

This study makes a contribution to research on the relationships among parenthood, drinking contexts, and alcohol intake. After analyzing the data, we found that a central result in this sample was that overall, when age, education level, and marital status were controlled for, parenthood was neither directly, nor conditionally, associated with alcohol intake per occasion. Although authors have previously pointed out that social roles have a conservative effect on overall drinking patterns (Celentano and McQueen, 1984; Paradis et al., 1999; Parker et al., 1980; Temple et al., 1991), our study indicates that, for both men and women, being the parent of a child younger than the age of 18 living at home is not significantly related to alcohol intake per occasion. More to the point in this study, we found that drinking contexts significantly influenced alcohol intake per occasion, but results of multilevel analyses provided very limited support for a moderator role for drinking contexts on the parenthood-alcohol intake relationship. Of the 10 possible interactions that were tested between parenthood and contextual variables across gender categories, only one reached statistical significance, and it was not in the predicted direction.

The nature of the interaction between men's parental role and circumstances is intriguing. The results showed that nonfathers drank more than fathers in every type of circumstance except in get-togethers, where, surprisingly, it is fathers who drank the most. No explanation can be offered for this result, unless it is that this circumstance has a different meaning that is related to different acceptable behaviors for fathers and nonfathers. For fathers, the get-together could be a true time-out, unconnected to other parts of the day (life) and subject to different rules (Gusfield, 1963). Indeed, unlike nonfathers, who may consider a get-together to be a common situation, fathers may experience this particular drinking circumstance as an out-of-the-ordinary occasion, where “boys meet boys,” in a context that does not condemn, and perhaps supports, greater alcohol intake. Hence, fathers and nonfathers experiencing a given circumstance differently could explain this finding.

Besides this counter-intuitive result, the general failure to find context differences in the magnitude of the relationship between parenthood and alcohol intake brings something new to sociological perspectives on alcohol use like the opportunity perspective (cf. Knibbe et al., 1987). In view of present results, parents are not continuously constrained, and, therefore, a role perspective on alcohol use should be wary of putting too much emphasis on restrictions and responsibilities. Mothers and fathers may not always limit their alcohol intake but may, once in a specific drinking context, decide to adjust their drinking to what is customary in that context rather than limit their drinking to restrictive norms connected to their parental role. More than a case where parental responsibilities limit alcohol intake, it may be that drinking provides an excuse to lapse in parental responsibilities. As Gusfield (1996) points out, alcohol is the object that allows an individual to transform himself or herself from “a socially bound and limited player of roles into someone of self-expression” (p. 64).

In this study, we hypothesized a high level of cross-situational consistency among parents. We expected that, in every drinking context, even those with characteristics conductive to increased drinking, mothers and fathers would drink in such a way as not to interfere with parental duties. In point of fact, our results rather reaffirmed what had been previously observed in studies from the drinking context literature—that is, the robust influence of drinking contexts. Contextual characteristics explain variation between occasions, as well as between individuals on alcohol intake per occasion. This study's hierarchical design showed that, regardless of their individual characteristics, drinking in a bar, with a large group, during the weekend, and under a circumstance other than a daily one was significantly related to increased alcohol intake. Thus, the positive impact of these characteristics on alcohol intake cannot exclusively be the result of an autoselection bias that makes a certain type of individual more likely to encounter these contexts; rather, it is the result of the sole effect that these contextual characteristics have on alcohol consumption. We, like others (Demers et al., 2002; Kairouz et al., 2002; Kairouz and Greenfield, 2007), draw attention to the great explanatory power that contextual characteristics bring to the study of drinking behaviors. Situational forces are such that, once in a context that normatively supports heavy drinking, persons will drink more than in a context that does not. In short, this study clearly points to the power of situations: Occasio furem facit.

Finally, we found that, when other sociodemographic variables were controlled for, the extent to which parenthood related to alcohol intake was significant among neither men nor women, even in heavy drinking contexts. Alcohol consumption is indissociable from the social environment (Social Issues Research Center, 2000; Wells et al., 2005). Women and men alike feel that in certain situations they can take a time-out, meaning that the drinking context, rather than their parental role, determines what they consider suitable behavior in that context. Nevertheless, further studies might investigate whether this gender-neutral effect remains true across various subpopulations within Canadian society.

Limitations

Some methodological limitations may have affected the present results. The first is the relatively basic way in which the parental role was treated in the CAS—that is, with no regard for the qualitative aspects of the parental role, the level of commitment, and responsibilities experienced by parents. Taking into account these aspects might have revealed a different picture, but present data did not allow for such a complex description of the parental role.

Likewise, no specific attention was paid to the moderator effect model of contexts for different types of parents. In this regard, Avison and Davies (2005) showed that, for Canadian women, the association of parenthood with the frequency of having five drinks or more on one occasion may be different for single mothers compared with mothers in two-parent households. Present analyses kept the marital status constant, but no direct attention was given to this issue. This is an interesting topic that should be addressed in future research.

In addition, present data did not allow us to control for the age of children living at home. However, this may not have had a significant effect on our results, because recent work has shown that, although time directly spent on child care decreases as children age, the loss of parental time in rest and leisure remains constant as children grow (Craig, 2007). Each age comes with its own set of challenges; therefore, overall the demands on parents' lives remain relatively even regardless of children's age (Craig and Sawrikar, 2008).

Furthermore, in the CAS, respondents were asked about their last three drinking occasions only. Although this gave us large samples (ns = 1,079 among women and 926 among men) with enough power to detect interactions, moderator effects are difficult to detect in field studies (McClelland and Judd, 1993). Perhaps if respondents had been asked about five drinking occasions, as had been done in other surveys (for details see Demers, 1997; Demers et al., 2002), the present sample would have been larger and a greater number of interactions might have come out significant. It also is possible that an increase in the variety of drinking occasions reported by respondents might have generated a more systematic and stronger association between parenthood and overall alcohol intake per occasion.

On a different note, our findings might be the result of epistemological limitations in a quantitative alcohol research contexts. To date, most researchers have worked with the assumption that, in regard to social roles and alcohol consumption, an instrumental causality prevails. Although this may be partially true, the intentional causality might be important as well. Therefore, sociologists should try to understand the logic beneath men's and women's behaviors by more attentively studying their expectations and their intentions instead of taking them for granted.

It is important to state that the present study tested only whether the effect of parenthood on alcohol intake varies according to the context in which drinking occurs. Other pathways in which parenthood influences drinking may exist and could be investigated in future research.

Conclusion

In our attempt through populational data to reinstate social actors within situations, our analysis of the effect of being a parent on alcohol intake across various drinking contexts shows the parental role to be a poor predictor of alcohol intake across different types of contexts for men and women alike. Concurrently, the present results reveal the robust influence of contextual characteristics to explain individuals' alcohol intake per occasion. Given that the explanation of alcohol behaviors within the general Canadian population may lie as much in the situation as in the person, those responsible for alcohol-prevention programs may want to implement environmental services and policies, such as bans on low-price alcohol promotions in drinking outlets, year-round safe-ride-home services, or mandatory server-intervention training.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very thankful to the two anonymous referees for critically reading the article and for their useful comments. We are grateful to the staff at the Institute for Social Research at York University, to the firm Jolicoeur for assistance in implementing the survey, and especially to David Northrup and Renée Elspett-Koeppen of the Institute for Social Research for their contributions to the design of the survey.

Footnotes

Research funding was provided, in part, by a grant for IRSPUM-affiliated doctoral candidates to write scientific articles. The data used in this research are from the project “Gender, Alcohol and Culture: An International Study (GENACIS).” GENACIS is a collaborative international project affiliated with the Kettil Bruun Society for Social and Epidemiological Research on Alcohol and coordinated by GENACIS partners from the University of North Dakota, Aarhus University, the Alcohol Research Group/Public Health Institute, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, the University of Melbourne, and the Swiss Institute for the Prevention of Alcohol and Drug Problems. Support for aspects of the project comes from the World Health Organization, the Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources Programme of the European Commission (Concerted Action QLG4-CT-2001–0196), the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism/National Institutes of Health (Grants R21 AA012941 andR01 AA015775), the German Federal Ministry of Health, the Pan American Health Organization, and Swiss national funds. Support for individual country surveys was provided by government agencies and other national sources. The study leaders and funding sources for data sets used in this report are Canada, Kate Graham (principal investigator), Andrée Demers (co-principal investigator), Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Application no. 108626.

References

- Adlaf EM, Begin P, Sawka E, editors. Canadian Addiction Survey (CAS): A national survey of Canadians' use of alcohol and other drugs, prevalence of use and related harms: Detailed report. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlström S, Bloomfield K, Knibbe R. Gender differences in drinking patterns in nine European countries: Descriptive findings. Substance Abuse. 2001;22:69–85. doi: 10.1080/08897070109511446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avison WR, Davies L. Family structure, gender, and health in the context of the life course. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60(Special Issue II):S1 13–S1 16. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates FL. Position, role, and status: A reformulation of concepts. Social Forces. 1956;34:313–331. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield K, Gmel G, Wilsnack S. Introduction to special issue “Gender, culture and alcohol problems: A multi-national study.”. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006;41(Suppl. 1):i3–i7. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Canadian Addiction Survey 2004: Microdata eGuide (Revised) Ottowa, Canada: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, McQueen DV. Alcohol consumption patterns among women in Baltimore. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1984;45:355–358. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YI, Crittenden KS. The impact of adult roles on drinking among women in the United States. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;41:17–34. doi: 10.1080/10826080500318574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Reed MB, Holmes MR, Lange JE, Voas RB. Drunk in public, drunk in private: The relationship between college students, drinking environments and alcohol consumption. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:275–285. doi: 10.1080/00952990500481205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen IJ. Theories of action and praxis. In: Turner BS, editor. The Blackwell companion to social theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 1996. pp. 73–111. [Google Scholar]

- Correll SJ, Bernard S, Paik I. Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112:1297–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Cosper RL, Okraku IO, Neumann B. Tavern going in Canada: A national survey of regulars at public drinking establishments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1987;48:252–259. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig L. Contemporary motherhood: The impact of children on adult time. Surrey, England: Ashgate; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Craig L, Sawrikar P. Satisfaction with work-family balance for parents of early adolescents compared to parents of younger children. Journal of Family Studies. 2008;14:91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. Changes in Telephone Survey Nonresponse over the Past Quarter Century. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2005;69:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- de Fornel M, Quéré L. La logique des situations: Nouveaux regards sur l'écologie des activités. Paris, France: Editions de l'Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (Editions de l'EHESS); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Demers A. When at risk? Drinking contexts and heavy drinking in the Montreal adult population. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1997;24:449–471. [Google Scholar]

- Demers A, Kairouz S, Adlaf EM, Gliksman L, Newton-Taylor B, Marchand A. Multilevel analysis of situational drinking among Canadian undergraduates. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55:415–424. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elster J. Explaining social behavior: More nuts and bolts for the social sciences. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2007. Persons and situations; pp. 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G, Bloomfield K, Ahlström S, Choquet M, Lecomte T. Women's roles and women's drinking: A comparative study in four European countries. Substance Abuse. 2000;21:249–264. doi: 10.1080/08897070009511437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Encounters: Two studies in the sociology of interaction. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Behavior in public places: Notes on the social organization of gatherings. New York, NY: Free Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H. Multilevel mixed linear model analysis using iterative generalized least squares. Biometrika. 1986;73:43. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H. Multilevel statistical models. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H, McDonald RP. A general model for the analysis of multilevel data. Psychometrika. 1988;53:455–467. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H, Rasbash J. Efficient computational procedures for the estimation of parameters in multilevel models based on iterative generalised least squares. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 1992;13:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gusfield JR. Contested Meanings: The Construction of Alcohol Problems. University of Wisconsin Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gusfield JR. Symbolic crusade: Status politics and the American temperance movement. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hajema KJ, Knibbe RA. Changes in social roles as predictors of changes in drinking behaviour. Addiction. 1998;93:1717–1727. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931117179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC. Contextual drinking patterns among men and women. In: Seixas FA, editor. Currents in alcoholism: Psychiatric, psychological, social and epidemiological studies. Volume 3. New York, NY: Grune and Stratton; 1978. pp. 287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC. Beverage specific drinking contexts. International Journal of the Addictions. 1979;14:197–205. doi: 10.3109/10826087909060365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Dorman N, Feinhandler SJ. Alcohol consumption in bars: Validation of self-reports against observed behavior. Drinking and Drug Practices Surveyor. 1976;11:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Gaines LC. Social drinking contexts. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Wechsler H, Rohman M. The structural context of college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1983;44:722–732. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1983.44.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy M, Saltz RF. Modeling social influences on public drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:139–145. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmila M, Raitasalo K. Gender differences in drinking: Why do they still exist? Addiction. 2005;100:1763–1769. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox JJ, Kreft IGG. Multilevel analysis methods. Sociological Methods and Research. 1994;22(3):283. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Anderson Z, Morleo M, Bellis MA. Alcohol, nightlife and violence: The relative contributions of drinking before and during nights out to negative health and criminal justice outcomes. Addiction. 2008;103:60–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joas H. The creativity of action. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kairouz S, Gliksman L, Demers A, Adlaf EM. For all these reasons, I do. drink: A multilevel analysis of contextual reasons for drinking among Canadian undergraduates. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:600–608. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kairouz S, Greenfield TK. A comparative multi-level analysis of contextual drinking in American and Canadian adults. Addiction. 2007;102:71–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knibbe RA, Drop MJ, Muytjens A. Correlates of stages in the progression from everyday drinking to problem drinking. Social Science and Medicine. 1987;24:463–473. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche S, Gmel G, Knibbe RA, Kuendig H, Bloomfield K, Kramer S, Grittner U. Gender and cultural differences in the association between family roles, social stratification, and alcohol use: A European cross-cultural analysis. Alcohol and Alcoholism Supplement. 2006;41:i37–i46. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche S, Knibbe RA, Gmel G. Social roles and alcohol consumption: A study of 10 industrialised countries. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;68:1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Paschall MJ, Maclennan B, Langley JD. Intoxication by drinking location: A web-based diary study in a New Zealand university community. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2586–2596. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E. Maturing out of substance use: Selection and self-correction. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26:457–476. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:285–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, Judd CM. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:376–390. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline AC, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use among adults 35 years of age: Prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt JD. The social integration of beers and peers: Situational contingencies in drinking and intoxication. In: Pittman DJ, White HR, editors. Society, culture, and drinking patterns reexamined. New Brunswick, NJ: Center of Alcohol Studies, Rutgers University; 1991. pp. 198–215. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis C. A mediational model of the relationship between the parental role and heavy drinking among Canadian adult drinkers: The influence of drinking locations. Lausanne, Switzerland: Paper presented at the 36th Annual Alcohol Epidemiology Symposium of the Kettil Bruun Society; 2010, June. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis C, Demers A, Nadeau L. Positional role changes and drinking patterns: Results of a longitudinal study. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1999;26:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Parker DA, Wolz MW, Parker ES, Harford TC. Sex roles and alcohol consumption: A research note. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1980;21:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Saltz RF. Relationships between college settings and student alcohol use before, during and after events: A multi-level study. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2007;26:635–644. doi: 10.1080/09595230701613601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Labrie J. Partying before the party: Examining prepartying behavior among college students. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:237–245. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.3.237-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasbash J, Steele F, Browne W, Prosser B. A user's guide to MLwiN, version 2.0. London, England: Centre for Multilevel Modelling, Institute of Education, University of London; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J. Do response rates matter in RDD telephone survey? 2006. Retrieved from http://pri.sfsu.edu/New_Folder/corner.html.

- Shore ER. The relationship of gender balance at work, family responsibilities and workplace characteristics to drinking among male and female attorneys. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:297–302. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpura J. Drinking contexts and social meanings of drinking: A study of Finnish drinking occasions. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Simpura J. A typical autumn week's drinking. In: Simpura J, editor. Finnish drinking habits: Results from interview surveys held in 1968, 1976, and 1984. Vol. 35. Helsinki, Finland: The Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies; 1987. pp. 78–103. [Google Scholar]

- Simpura J. Studying norms and context of drinking. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1991;18:477–498. [Google Scholar]

- Single E, Wortley S. Drinking in various settings as it relates to demographic variables and level of consumption: Findings from a national survey in Canada. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:590–599. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Issues Research Centre. Social and cultural aspects of drinking: A report to the Amsterdam Group. Oxford, England: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Modeled variance in two-level models. Sociological Methods and Research. 1994;22:342–363. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London, England: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Snow RW, Landrum JW. Drinking locations and frequency of drunkenness among Mississippi DUI offenders. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1986;12:389–402. doi: 10.3109/00952998609016878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes RE, Rowley RD, Schaefer JM. The influence of time, gender and group size on heavy drinking in public bars. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:133–138. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple MT, Fillmore KM, Hartka E, Johnstone B, Leino EV, Motoyoshf M. A meta-analysis of change in marital and employment status as predictors of alcohol consumption on a typical occasion. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1269–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trewin D, Lee G. International comparisons of telephone coverage. In: Groves RM, Biemer PP, Lyberg LE, Massey JT, Nicholls WL, Waksberg J, editors. Telephone Survey Methodology. New York, NY: Wiley; 1988. pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Graham K, Speechley M, Koval JJ. Drinking patterns, drinking contexts and alcohol-related aggression among late adolescent and young adult drinkers. Addiction. 2005;100:933–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.001121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Vogeltanz ND, Wilsnack SC, Harris TR. Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: Cross-cultural patterns. Addiction. 2000;95:251–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95225112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]