Abstract

The rapidly changing demographics of the United States require nurses who are equipped with knowledge and skills to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse patient population. Nurse educators seek to meet this challenge through integrating cultural competence into nursing course curricula. Few studies have examined student perceptions of the integration of this material. As part of a larger school wide assessment, this qualitative descriptive study utilized focus groups of PhD and BSN students to evaluate their perceptions of the integration of cultural competence in the nursing curriculum. We sought to answer two questions: 1.) what the students’ perceptions were and 2.) what recommendations they had for improvement. The results of the focus groups yielded three themes: 1.) Broadening definitions, 2.) Integrating cultural competence, and 3.) Missed opportunities. Student suggestions and recommendations for enhancing cultural competence in the curricula are provided.

Keywords: Cultural competence, nursing curriculum, student perceptions, focus groups

Introduction

Student nurses entering the current healthcare arena will face a complex, rapidly changing environment filled with consumers from diverse backgrounds. Ethnic and racial minorities are now one third of the U.S. population and are expected to comprise more than 54 percent by 2050, (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). These demographic shifts are occurring in the wake of enduring health disparities among many racial and ethnic minorities, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and other marginalized groups. While the causes of poorer health in these groups are complex, studies, such as the Institute of Medicine [IOM] report, indicate that the sources of health disparities occur at several levels, including that of the health care provider (Smedely, Stith & Nelson, 2002). Nurses are on the frontline of health care provision in this nation, and as such must be prepared and adequately trained while in school to meet the needs of the diverse population they will serve. The inability to do so may result in dire consequences and continue to perpetuate poor health outcomes among minority groups.

The barriers some student nurses encounter in caring for diverse populations may be due to a lack of training and skill in providing culturally and linguistically competent care. To meet this challenge, many nurse leaders and educators are seeking to increase the levels of cultural competence among student nurses as a part of organizational strategic goals (Watts, Cuellar, O’Sullivan, 2008, Giger et al, 2007). Most schools of nursing now offer students a variety of culturally relevant materials within the teaching curricula. These materials however, often vary across institutional settings, thus resulting in mixed outcomes. While examples of various models of cultural competence in nursing schools exist in the literature, few studies explore the effectiveness of these strategies or the beliefs and perspectives of the very audience they seek to reach- the student. Hence, this paper describes the results of a descriptive qualitative descriptive study using focus groups, which explored the views of undergraduate and doctoral students regarding their perceptions of cultural competence within the nursing curriculum. The study was conducted as a component of a larger initiative to evaluate and integrate cultural competence into the nursing curriculum at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing between 2002-2008. The results of the study were used as part of the development of a blue print for enhancing cultural competence education.

Background

University Commitment to Enrich Cultural Competence

In order to continue its commitment to diversity awareness, the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing set as its primary goal in the 2003-2008 strategic plan, the integration of cultural competence throughout the research, practice and education agenda (Watts, Cuellar, O’Sullivan, 2008). Efforts to meet this objective included the appointment of a Director of Diversity Affairs and the introduction of an intensive faculty development program which included training sessions, regional workshops and a seminar series on diversity and cultural competence, (Watts et al,2008). Financial resources were also allocated to support diversity conferences, curricular consultations with nationally and internationally renowned experts and diversity recruitment efforts (Siantz and Meleis, 2007, Watts, Cuellar, O’Sullivan, 2008).

In 2002, the Master Teachers Taskforce on Cultural Diversity was introduced to advance the school’s diversity agenda. Comprised of standing faculty, course directors, program directors, and students, one of the missions of the taskforce was to assess the school’s curriculum and to provide recommendations on methods for integrating cultural competence. Over a period of five years, taskforce members collected data regarding the state of cultural competence in the nursing curriculum through a variety of methods. One of the major culminating efforts of the taskforce was the development of a Blueprint for Integration of Cultural Competence in the Curriculum (BICCC), introduced as a teaching guide and measurement tool for faculty and students. Using the BICCC, quantitative and qualitative data from faculty and students were collected to gather perceptions of the inclusion of cultural-specific content in their courses (Brennan & Cotter, 2008). The taskforce’s desire to solicit targeted student feedback of their experiences with cultural-related content in their nursing courses led to this smaller student-conducted study. The research questions that guided our study were:

What are undergraduate and graduate students’ perceptions of cultural competence and its integration into the school of nursing curriculum?

What recommendations do students have for strengthening the integration of cultural competence-related information into the school of nursing curriculum?

Methods

In this qualitative descriptive study we conducted two focus groups comprised of nursing students at the University of Pennsylvania in the spring of 2006 and 2007. This design allowed us to gain a preliminary understanding of the student’s views and perceptions of cultural specific content in their nursing courses (Sandelowski, 2000). Focus groups provided a format for participants to provide spontaneous reactions, reflect on personal experiences, verbalize opinions, and hear the experiences of others and compare (Ruff, Alexander, McKie, 2005).

Setting and sample

The study was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. The majority of the enrolled students are White (62%) females (94%) seeking their first degree (75%). The standing faculty of the school is also predominantly White (88%) and female (91%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics for the School of Nursing

| Demographic | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BSN N=507 |

PhD N=56 |

Faculty N=56 |

|

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| American Indian | 1 (0.2%) | -- | -- |

| Asian | 92 (18%) | 7 (13%) | 3 (6%) |

| Black | 25 (5%) | 5 (9%) | 3 (6%) |

| Hispanic | 18 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| White | 316 (62%) | 35 (63%) | 49 (88%) |

| Other | 3 (0.6%) | 1 (2%) | -- |

| Not Reported | 52 (10%) | 7 (13%) | -- |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 477 (94%) | 53 (95%) | 51 (91%) |

Percents may not equal 100 due to rounding

Participants were recruited electronically via the nursing student body and doctoral student listservs, and through flyers posted in the School of Nursing. Dinner was provided for the students as compensation for their time. Inclusion criteria required that all participants had completed at least one semester of course work in order to participate. Each focus group was demographically mixed and included students at various stages of matriculation. The doctoral focus group participants (N=5), included one male, three Whites and, two Hispanics and two first year and three second year student. The undergraduate focus group (N=5 ) included all female participants, two with a previous degree and three “traditional” BSN students in either their sophomore, junior, or senior year in the program. The participants in the BSN focus group did not report race or ethnicity. The number of participants was in agreement with Krueger and Casey’s Focus Groups, where the authors state that the size of a typical focus group can range from 4-12 participants (Kreuger, Casey 2000). All procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania. Individual verbal consent was obtained prior to beginning each focus group.

Data Collection

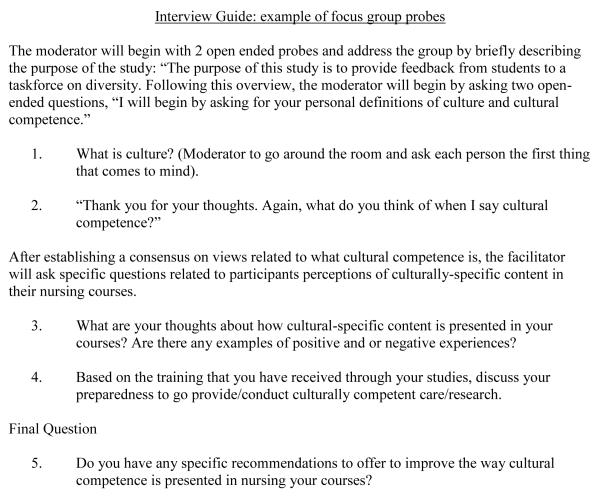

Focus group procedures followed methods used by Ruff, Alexander, and McKie and included two moderators, one who facilitated the discussion, while the other recorded verbal and non- verbal communication via digital recorder and field notes (2005). Each focus group lasted between 1.5-2 hours. Both interview guides consisted of five questions, moving from general to specific (Sharts-Hopko, 2001). The main differences between the interview guides were the focus on clinical practice application for BSN students and on research application for doctoral students. The facilitator used a series of probes to guide the focus group sessions. The interview guide began with probes to get initial reactions to trigger words such as “culture” and “cultural competence” and to establish a working definition of what students were evaluating. After the initial probe, participants were asked to carefully evaluate their experience of the presentation of culturally-specific content in their nursing courses. In addition, they were asked to discuss useful methods employed by some instructors to integrate cultural competence into course material as well as the “missed opportunities” of others. The facilitator encouraged participation from all members of the group and students ended each focus group by providing concrete suggestions for improvements. A sample of the focus group questions is presented in Figure 1. All audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist. Detailed notes were taken during the focus group to augment the transcripts of the audio recordings.

Fig 1.

Data Analysis

Qualitative content analysis was used to interpret results. First, transcripts were reviewed by team members for significant statements, and these statements and similar concepts were grouped together to generate themes as data analysis progressed. Second, codes were discussed and placed into categories. Third, to augment rigor, the transcripts were coded separately by each facilitator then reviewed together to reach a consensus. The validity of the themes from the doctoral focus group was reinforced by performing member checks with another group of doctoral students. The fourth and final step was organizing the data using Atlas.ti 5.0 software. Common points of agreement and difference between the groups were also identified during the analysis process.

Findings

Participants in the doctoral and BSN focus groups expressed substantive comments ranging from the content of the nursing curriculum to their own personal experiences in the classroom and clinical settings. Three salient themes emerged: 1.) Broadening definitions, 2.) Integrating cultural competence, and 3.) “Missed opportunities”.

Theme 1: Broadening Definitions

Members of both focus groups expressed concerns regarding the use and meaning of the term “cultural competence.” Many believed that cultural competence and related terms had become so overused they lacked contextual meaning and depth. When asked about cultural competence and related terms, students gave varying definitions and one student felt “what you label them is probably always going to be up for debate…” while another student confessed, “I’m not even sure how you are defining cultural competence…”.

While definitions of terms appeared ambiguous, students did share a desire to move past the language and practice of stereotyping. One student thought “the most important thing to do is to keep an open mind about your patient,” in order to think about culture in a broader sense. Another student expressed it this way, “I found that cultural competence in this school of nursing has not helped me at all. It’s just really made me close my eyes to other things that could be going on.” Another frustrated student recounted a testing experience, “…they did this whole cultural section and they made me so mad because it was multiple-choice. Depending on what the culture was, I had to say they would do this.” Being forced to put individuals in boxes led another student to feel that “when they do competence here…I feel it’s hollow.”

This desire for a more open-minded approach may have been prompted by self-reflection as one student stated she “wouldn’t want to be stereotyped based on my culture the way someone outside might expect me to behave”. Another student held similar concerns after having been singled out because of her own cultural identity “…lots of times teachers really do stuff that isn’t okay, but I feel like they don’t realize it. Because there will be times in class and we’ll talk about a certain culture and then they’ll pick on me, because of whatever culture I have. And they’ll say, ‘What do you think…’?” The students in both groups never settled on a single definition to describe cultural competence and related terms, but each group sought an approach which diminished stereo-typing and fostered patient care based on individual attributes versus generalizations about group characteristics.

Theme 2: Integrating Cultural Competence

Though the focus of the undergraduate curriculum and the doctoral curriculum differed, the students in both focus groups shared similar concerns about their ability to integrate cultural competence into research and clinical practice. Doctoral students expressed concerns regarding their ability to conduct culturally competent research. Their comments centered around the ability to recruit and retain representative samples and in obtaining true informed consent. One student felt “…a class on research methods should be about… how to be sensitive to getting an adequate distribution of different ethnic groups in your sample.” While another saw it as an issue broader than race and ethnicity and regretted that, “we never really talked about consenting people who have cognitive impairments, consenting people of other races, and…who speak other languages, English is not their first language; they can’t read or write, you know all of those other issues happen, and it’s not all about race and ethnicity, I mean there are…issues of marginalized groups”.

Undergraduates were similarly concerned about their ability to integrate cultural competence into their clinical practice, though some students expressed mixed views on their ability to do so. One student felt “…more prepared because my eyes have been opened to the fact that I don’t know a lot about this. I think it can cut both ways. I’m more prepared to have trouble with it. I think I came into nursing school as a second degree student feeling a little bit over confident about my ability to interact with other cultures. Because I had had positive experiences in the past and doing it as a nurse is very different than doing it as someone else.” Another student felt that she would have been more adequately prepared to integrate cultural competence into her nursing practice had basic communication techniques been stressed. She explained it this way, “[And] the best thing I’ve always found in any culture is just saying, ‘Is this okay?’ before you do it. And if they could just teach that in five minutes I think that would be more helpful. Like if it was my Muslim man patient I had, I’d be like, ‘Is it okay if I help you go to the bathroom?’ And for him it was and he’s not every single Muslim male patient I’ll ever see.”

Theme 3: “Missed opportunities”

Another theme surfacing from the focus group involved faculty issues and what the students perceived as missed opportunities to teach cultural competence. One student felt there were “a lot of opportunities in our classes that have been missed and it may just be…an inability to integrate it somehow. And I’m not faulting them, I think it’s just kind of obvious though, and maybe they need training in how to do it from the school of nursing; maybe funds need to be put into advanced teacher training for them.” Another student felt there were times when instructors “…could have actually done more…” with certain classroom situations that arose. Ironically this was especially true with uncomfortable moments as one student described, “…there was sort of like a silence, and that would have been a key moment that we really should’ve explored more thoughts…” Other students believed research faculty should draw from their personal experiences with diverse research populations to instruct students on ways to navigate this process.

Discussion

The last half of the 20th century has witnessed an increase in literature and research supporting the incorporation of cultural competence into holistic nursing practice. During this period, nurse leaders have developed several theoretical models, which describe cultural competence, and its various components (Camphina-Bacote, 1994; Giger and Davidhizar, 1995, Leninger, 1978, Purnell and Paulanka, 1998). These models have served as useful guides for introducing cultural competence into the nursing curricula, though as this study demonstrates, the integration of these models into didactic and practicum settings has varied.

The collective response from the participants in this study reveals that while nursing students receive course content involving cultural competence, this exposure does not necessarily translate into perceived mastery of the subject. The participants stressed the need for teaching methods which more comprehensively probed the meaning of familiar buzz phrases such as “cultural diversity,” “cultural sensitivity,” and “cultural competence” since frequently these phrases were understood along racial lines, which set up automatic defenses and discomfort among some students. Establishing definitions which move beyond racial and ethnic identity may reduce these tensions while at the same time helping students to appreciate the differences (and similarities) existing within and between groups. Students expressed the desired to move away from the stereotyping of groups and individuals towards having a more open mind and a broader definition of culture. Students were frustrated with “placing people and groups in boxes,” based on behaviors that were believed to be group norms. Students increasingly desired a dialogue about these subjects which interrogated and probed their current understandings and challenged them to think about their own biases as well as those of others.

We acknowledge a significant limitation of this study, which was the small number of focus groups, which may have decreased the representativeness of the study participants and their viewpoints. However, this is one of the disadvantages of focus group data in general. We attempted to minimize these limitations by: 1) the selection of participants from the same school of nursing; 2) the composition of the focus groups, i.e., PhD and BSN specific; and 3) the use of a structured interview guide.

Despite the limitations posed by small sample size, our findings are consistent with those of Walsh Brennan and Cotter (2008) who completed a mixed methods study of cultural competence in the undergraduate and Master’s curricula at the same university. In their study students answered an open-ended probe at the end of the BICCC. Results from the qualitative portion revealed that while cultural information was presented throughout the undergraduate curricula, it was often covered at the same depth throughout the curriculum in a redundant fashion. These results, along with ours, underscore the importance of measurement and evaluation tools such as the BICCC as it provides a framework to appropriately level the objectives of learners so that culture-specific content sequentially builds the skills, attitudes, and knowledge of students while avoiding duplication and redundancy of course materials.

Doctoral and undergraduate nursing students reported mixed views on their ability to provide and conduct culturally competent care and research. Several reasons may account for this occurrence. First, variation in these responses may have arisen from students being at different phases in their nursing studies. Previous studies of nursing students revealed that senior nursing students and graduate students reported sufficient levels of teaching in response to survey questions, (87%) and (90%) respectively, while freshman reported less exposure (25%) to cultural content (Walsh Brennan & Cotter, 2008). The variation in responses may have also resulted from different types of exposures. Students often have courses with a large array of lecturers, clinical preceptors and standing professors, as well as exposure to humanities courses throughout the university. Each educator may present this information in a different manner, depending on her/his comfort level and style. Some faculty may approach cultural competence in a “content” oriented way, which places heavy emphasis on theory and “what it is.” Other educators teach the “process” of obtaining cultural information and applying it to the nurse-patient relationship (Lipson & DeSantis, 2007). While each approach has merit, it is difficult to assess which is of most benefit to students. As a measure to ensure a degree of consistency and to enrich the learning experience for students, focus group respondents endorsed increased faculty training in the subject matter in hopes that it would produce a wider variety of methods used to introduce the topic of cultural competence. This type of training should guide instructors in recognizing “teachable moments” and avoiding the “missed opportunities”, and being mindful of the “informal curriculum” or body language and side comments about the subject matter (Betancourt, 2007), which may leave students the impression that the content is mere “lip service”.

Part of the challenge facing instructors in presenting cultural competence may be associated with culture- related nursing theories framed within the biomedical model, which emphasizes biological/physical traits while excluding psychological and social variables (Dorazio-Migliore, Migliore, & Anderson, 2005). Recently scholars have challenged this convention advocating instead for a view which considers culture within broader political, economic and historical contexts (Lynam, Browne, Kirkam, & Anderson, 2007). These authors contend that it may be necessary to shift paradigms and ways of knowing and thinking about the concept of culture in order to more fully grasp its complexity. Such a challenge moves cultural discourse beyond descriptions ‘of’ culture towards an understanding of culture as dynamic and demonstrates how cultural practices create contexts that have the potential to foster or impede health (Lynam, Browne, Kirkam, & Anderson, 2007). While cultural features may be identified and described, it should be emphasized that they hold varying degrees of meaning and may be adopted selectively by individuals within that culture. Culture and its associated traditions will not be viewed the same by all members of that group, and representations of culture as a static set of beliefs and practices attributable to a particular group are inadequate conceptualizations that mask within-group diversity (Lynam, Browne, Kirkam, & Anderson, 2007).

Recommendations

The doctoral and undergraduate students did not merely offer critique of their nursing curricula, they also offered concrete recommendations they thought would improve the delivery of culture-related content. The students would rather have the cultural content saturate the course, not just limited to one special lecture but a constant presence in the curriculum to mimic real life. They thought it should be woven throughout the course similar to the way the life span is integrated into their undergraduate nursing courses. Both groups suggested training for faculty, including incentives for them to obtain the training. This training would help increase the comfort level of the instructors with the material and provide teaching strategies. It would also teach instructors how to utilize their own research and/or clinical practice, modeling reflective practice for the students. The students desired more readings from the humanities, which they felt covered cultural topics in more depth than the readings from the sciences they were assigned. They welcomed the idea of being challenged and wanted instructors to help facilitate the examination of biases and personal philosophies about culture. Students also wished to hear from graduates who are currently putting this material into practice and how they navigate the culture-related issues of their respective facilities.

The students desired more discussion and dialogue (and less papers) in the classroom as well as in their clinical sites. One way to achieve this goal is through creating seminar style discussion opportunities where students might more openly share their thoughts and perspectives. One of the features of the focus groups was that it allowed free expression. Several students reported that the focus group served as “the best discussion they had participated in since beginning nursing courses.” They felt attendance to diversity lectures would increase if students were given credit for writing a summary, critique, or reflection on the event.

Conclusion

Results from this study add to ongoing efforts to integrate cultural competence into the school of nursing curriculum. Student feedback such as that provided through focus groups serves as a valuable barometer to evaluate current methods for integrating this content. As a result of this and other Master Teacher Task Forces efforts, the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing has added several new courses to the nursing curricula as well as a new minor in Multicultural/Global Healthcare. They have also instituted monthly informal brown bag-style discussions open to all students, faculty, and staff. These sessions serve several purposes: to create a “safe space” to freely discuss topics in depth that might not be broached in the classroom or clinical site, provide faculty an opportunity to witness successful navigation of difficult topics (role-modeling), and to allow the intellectual exchange between individuals at every level of the school of nursing community. The study institution also continues to sponsors a diversity lecture series, which the students did find valuable. These additions will allow students to develop advanced knowledge and skills in domestic and national health care contexts. As schools of nursing continue to rise to the challenge of equipping their students with the skills and tools necessary to provide and conduct culturally competent care and research, the strategies employed by the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing may provide a useful collaborative model.

Acknowledgments

J. Margo Brooks Carthon, is a post doctoral fellow supported by funding from the National Institute for Nursing Research, national Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (RO-1NR-004513, Aiken, PI) and the Center for Nursing Outcomes Research (T-32-NR-007104, Aiken, PI).

This work was also supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (P20 NR008361) Awarded to the University of Pennsylvania and Hampton University (Jemmott, L.S. & Davis, B. PIs) 09/30/02 – 06/30/07

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Danica Fulbright Sumpter, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing Room 214 Fagin Hall 418 Curie Blvd. Philadelphia, PA 19104 (215)898-3216 dsumpter@nursing.upenn.edu.

J. Margo Brooks Carthon, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing University of Pennsylvania, School of Nursing 418 Curie Blvd Philadelphia, PA 19104-6096 jmbrooks@nursing.upenn.edu 856-985-9851/fax: 856-985-9955.

References

- Anderson JM. Toward a post-colonial feminist methodology in nursing research: Exploring the convergence of post-colonial and black feminist scholarship. Nurse Researcher. 2002;9(3):7–27. doi: 10.7748/nr2002.04.9.3.7.c6186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JM, Kirkham SR, Browne AJ, Lynam ML. Continuing the dialogue: Postcolonial feminist scholarship and bourdieu -- discourses of culture and points of connection. Nursing Inquiry. 2007;14(3):178–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2007.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt JR. Commentary on “Current approaches to integrating elements of cultural competence in nursing education”. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(1):25S–27. doi: 10.1177/1043659606295498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan A, Cotter VT. Student perceptions of cultural competence content in the curriculum. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2008;24(3):155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan C, Wtmore-Akader L, Calvano T, Deatrick JA, Giri VN, Bruner DW. Using Focus Groups to Adapt Ethnically Appropriate, Information-Seeking and Recruitment Messages for a Prostate Cancer Screening Program for Men at High Risk. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008;100(6):674–682. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31340-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote J. Cultural competence in psychiatric mental health nursing. A conceptual model. The Nursing Clinics of North America. 1994;29(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MA, Smith MW. Capturing the group effect in focus groups: A special concern in analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 1994;4(1):123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Day JC. Population Projections of the United States by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1995 to 2050. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, P25-1130. 1996

- de Leon Siantz ML, Meleis AI. Integrating cultural competence into nursing education and practice: 21st century action steps. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(1_suppl):86S–90. doi: 10.1177/1043659606296465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorazio-Migliore M, Migliore S, Anderson JM. Crafting a praxis-oriented culture concept in the health disciplines: Conundrums and possibilities. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness amp; Medicine. 2005;9(3):339–360. doi: 10.1177/1363459305052904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger JN, Davidhizar RE. Transcultural nursing: Assessment and intervention. Mosby-Year Book; St. Louis, MO: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Giger J, Davidhizar RE, Purnell L, Harden JT, Phillips J, Strickland O. American academy of nursing expert panel report: Developing cultural competence to eliminate health disparities in ethnic minorities and other vulnerable populations. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(2):95–102. doi: 10.1177/1043659606298618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuger D, Cassey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 3rd ed. Sage Publications, Ltd.; Thousands Oaks: 2000. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M. Changing foci in American nursing education: Primary and transcultural nursing care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1978;3(2):155–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1978.tb00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipson JG, Desantis LA. Current approaches to integrating elements of cultural competence in nursing education. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(1_suppl):10S–20. doi: 10.1177/1043659606295498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Qualitative content analysis: A guide to paths not taken. Qualitative Health Research. 1993;3(1):112–121. doi: 10.1177/104973239300300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnell LD, Paulanka BJ. Purnell’s model for cultural competence. In: Purnell L, editor. Transcultural health care: A culturally competent approach. F.A. Davis; Philadelphia, PA: 1998. pp. 7–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff CC, Alexander IM, McKie C. The use of focus group methodology in health disparities research. Nursing Outlook. 2005;53(3):134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharts-Hopko NC. Focus group methodology: When and why? Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2001;12(4):89–91. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, stith AY, nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethinc disparities in health care. National Academic Press; Washington, D.C.: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yearwood EL, Brown DL, Karlik EC. Cultural diversity: Students’ perspectives. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002;13(3):237–240. doi: 10.1177/10459602013003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]