Abstract

Background

Atherosclerosis is widely accepted as an inflammatory disease involving both innate and adaptive immunity. B cells and/or antibodies have previously been shown to play a protective role against atherosclerosis. Aside from their ability to bind to antigens, antibodies can influence inflammatory responses by interacting with various Fcγ receptors on the surface of antigen presenting cells. Although studies in mice have determined that stimulatory Fcγ receptors contribute to atherosclerosis, the role of the inhibitory Fcγ receptor IIb (FcγRIIb) has only recently been investigated.

Methods and Results

To determine the importance of FcγRIIb in modulating the adaptive immune response to hyperlipidemia, we generated FcγRIIb-deficient mice on the apoE-deficient background (apoE/FcγRIIb−/−). We report that male apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice develop exacerbated atherosclerosis that is independent of lipid levels, and is characterized by increased antibody titers to modified LDL and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the aorta.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that antibodies against atherosclerosis-associated antigens partially protect against atherosclerosis in male apoE−/− mice by conveying inhibitory signals through the FcγRIIb that downregulate pro-inflammatory signaling via other immune receptors. These data are the first to describe a significant in vivo effect for FcγRIIb in modulating the cytokine response in the aorta in male apoE−/− mice.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, Fc receptor, apoE, lipoproteins, inflammation

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by thickening of the artery wall and retention of modified low density lipoproteins (LDL), resulting in foam cell formation and infiltration of immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells, T cells, B cells and NK cells. Both adaptive and innate immune responses have been shown to be important to this disease 1–4. Studies from our laboratory and others have shown that B cells and/or antibodies, components of the adaptive arm of immune responses, can protect against atherosclerosis 5–8. In addition, both passive and active immunization with oxLDL can decrease atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic animals 9–12. Naturally occurring IgM or induced IgG antibodies to oxLDL may exert this protective function by inhibiting the uptake of oxLDL by scavenger or LDL receptors or by interacting with Fc receptors expressed on the surface of various immune cells.

Fcγ receptors (FcγR) are found on immune cells such as macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, dendritic cells and B cells, and they can be either activating (FcγRI, FcγRIII and FcγRIV) or inhibitory (FcγRIIb) 13, 14. Activating FcγR contain an intracellular tyrosine activating motif (ITAM) and have high affinity for the IgG Fc region. In contrast, the intracellular portion of the low affinity FcγRIIb contains an intracellular inhibitory motif (ITIM). Whereas binding of FcγRI and FcγRIII results in the activation of various cell functions that are cell type-dependent, binding of the low affinity FcγRIIb by immune complexes (IC) results in decreased immune cell activation.

Several observations in humans suggest a regulatory role for FcγRs in atherosclerosis. In vivo, FcγRs have been shown to be expressed in human atherosclerotic lesions, and previous studies in apoE−/− mice using passive immunoglobulin infusion decreased atherosclerosis, implicating the interaction of immune complexes with FcγRs 15, 16. Moreover, polymorphisms in FcγRIIa in humans, which also serves as a receptor for C-reactive protein, have been associated with acute coronary syndrome or protection against atherosclerosis 17, 18. In vitro, oxLDL-IC have been shown to signal through FcγR in human macrophage cell lines 19, 20, and FcγR have also been hypothesized to be important in inflammation and foam cell formation by facilitating macrophage uptake of modified lipoprotein complexed to antibodies 21, 22. A similar function for FcγRIIb in macrophages has not been established. In addition, it is currently not known how FcγRIIb modulates cellular responses to a hyperlipidemic environment in vivo.

Two recent studies using mice deficient in the expression of the activating FcγRI and FcγRIII on the apoE−/− or LDLR−/− backgrounds, showed a reduction in the atherosclerotic lesion, suggesting an atherogenic role for activating FcγR in atherogenesis 23, 24. These studies suggested that because the inhibitory FcγRIIb was still functional, atherosclerosis-susceptible animals were partially protected against atherosclerosis. More recently, Zhao, et al. 25 reported that transplantation of FcγRIIb-deficient bone marrow into female LDLR−/− mice fed a high fat diet results in increased atherosclerosis, suggesting a role for FcγRIIb in inhibiting atherosclerosis. Although this study showed immunological changes associated with a deficiency in FcγRIIb expression, it did not directly address the mechanism by which these immunological changes occur.

To determine the importance of the low affinity inhibitory FcγRIIb in modulating immune responses that lead to atherosclerosis, we generated FcγRIIb-deficient mice on the apoE-deficient background. In this study, we report that immunological changes, rather than changes in lipid levels, result in exacerbated atherosclerosis in the absence of FcγRIIb. Specifically, we show that male mice lacking FcγRIIb expression have an increased pro-inflammatory cytokine response in the aorta. Therefore, we provide evidence to support the hypothesis that antibodies against oxLDL protect against atherosclerosis by conveying inhibitory signals via the FcγRIIb which results in downregulation of pro-inflammatory signaling. These data are the first to describe a significant in vivo role for FcγRIIb in modulating the cytokine response in the aorta of apoE−/− mice.

Methods

Animals

B6;129S4-Fcgrbtm1Ttk/J (stock number 002848 and hereafter referred to as FcγRIIb−/−) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and have been previously described26. ApoE−/− mice are maintained and readily available in our mouse colony. All mice were on the C57BL/6 background. ApoE/FcγRIIb−/− double deficient animals were obtained by breeding the FcγRIIb−/− mice to the apoE−/− mice. F1 heterozygous mice were then inter-crossed, and homozygous double knockout or apoE single knockout mice resulting from these crosses identified by PCR; the latter were used as syngeneic controls. Mice were housed and maintained according to approved Vanderbilt IACUC regulations.

Protocol and atherosclerosis studies

For all atherosclerosis studies, mice were maintained on a normal chow diet until the endpoint of the study. At 10 weeks of age, blood was obtained via retro-orbital venous plexus and serum collected for initial antibody measurements. At 17 and 34 weeks of age, mice were sacrificed and blood obtained for antibody and lipid measurements. Total serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels were measured by a colorimetric assay as previously described 7. Atherosclerotic lesion burden was quantified in the proximal aorta by oil-red-O staining as previously described7.

Laser capture microdissection (LCM)

To quantify the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in the atherosclerotic lesion, the aortic sinus of embedded frozen heart tissue was cut as a series of 10μm sections onto non-charged Special Select Microslides (VWR). Slides were sequentially dehydrated in ethanol followed by xylene. The slides were then dried for 30 minutes in a desiccator and stored for no more than 6 hours before dissection. Lesions from the aortic sinus were isolated from the slide using the Veritas LCM System (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA) and captured onto Capsure HS Caps (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA) with instrument settings of smaller spot size (7.5μm), 70–80mW power and 2ms duration. RNA from the cap was isolated using PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit protocol (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA). The RNA was frozen and stored at −80°C for later use in real-time PCR (RT-PCR).

Real-time RT PCR

To quantify the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in the atherosclerotic lesion, LCM RNA was first converted to cDNA using the cDNA Synthesis Kit protocol (Biorad). To increase the minimal target gene expression of inflammatory markers, cDNA was pre-amplified using the Taqman® PreAmp Master Mix Kit protocol (Applied Biosystems). The protocol’s individualized pooled assay mix was made by combining equal parts Mouse Taqman® gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems): CD3, CD68, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-23, MCP-1, TNFα, and human reporter gene 18s. Data were collected using SDS2.3 software, and the ΔΔCt values were calculated using the RQ Manager Software (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was normalized against 18S RNA.

Aortic cultures

Whole aortas where dissected from the aortic arch to the iliac bifurcation. The aortas were minced and cultured in 200μl of complete RPMI 10%FBS for 18hr at 37°C without exogenous stimulation. Supernatants from these cultures were collected to characterize the cytokine environment of the vasculature.

ELISAs

Secretion of IL-17A and IL-23 (p19/p40) were measured using the Ready-Set-Go! kits from eBioscience. Antibody levels to copper oxidized LDL (OxLDL) and to malondialdehyde modified LDL (MDA-LDL) were performed as previously described in detail 8.

Statistical Analyses

For data with normal distribution a Student’s t test was performed to determine statistically significant differences between experimental and control groups. Data that did not demonstrate normal distribution was analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test.

Results

Comparison of atherosclerosis development in apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice

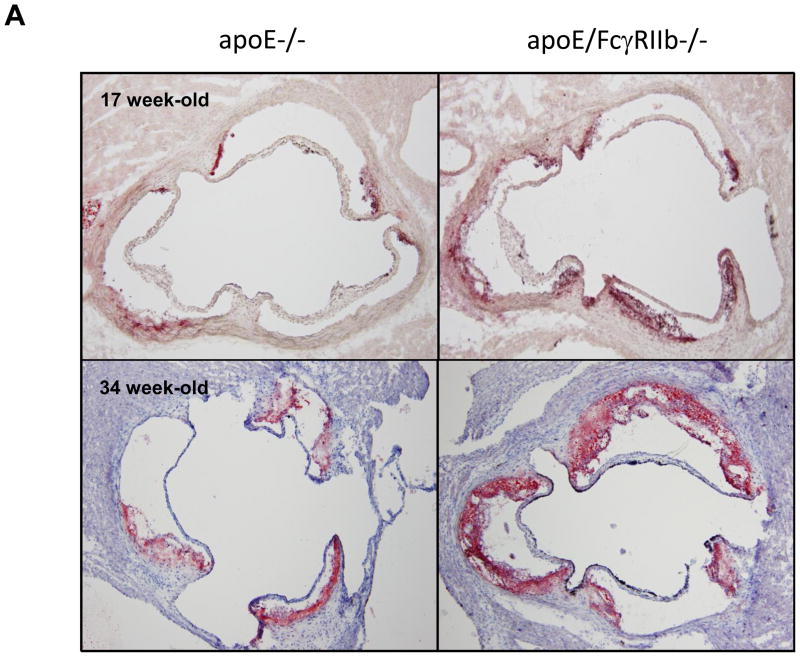

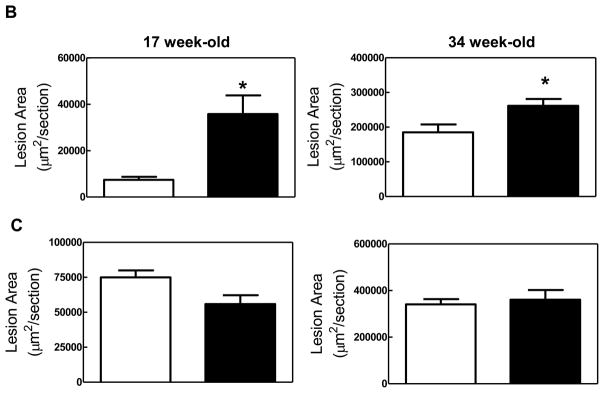

We hypothesized that inhibitory signals conveyed by immune complexes via the inhibitory FcγRIIb are important in controlling inflammation in hyperlipidemic mice, and that absence of FcγRIIb would result in exacerbated inflammation and atherosclerosis. To test this hypothesis, we compared atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic root of 17 and 34 week old apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice maintained on normal chow diet. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that male apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice develop larger lesions and accumulate more lipid than apoE−/− littermates (Figure 1A and 1B). However, when we compared lesion size in apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− female mice of the same age, the difference was not statistically significant, although we observed a trend towards decreased atherosclerosis at 17 weeks in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− females (Figure 1C). Since differential effects of estrogen on the immune system could result in differences in atherosclerosis, we limited our analysis to male mice.

Figure 1. Increased atherosclerosis in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice.

A) ORO-stained atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic root of male mice. B) Atherosclerotic lesion area in male mice. 17 w.o. n=5 apoE−/−; n=13 apoE/FcγRIIb−/−; 34 w.o. n=6 apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− C) Atherosclerotic lesion area in female mice. 17 w.o. n=4 apoE−/−; n=7 apoE/FcγRIIb−/−; 34 w.o. n= 9 apoE−/−; n=5 apoE/FcγRIIb−/−. D) Serum cholesterol and triglycerides from 17 w.o. male mice. n=9 apoE−/−; n=21 apoE/FcγRIIb−/−. *p<0.05 by Student’s t test.

To determine if the increase in atherosclerosis in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice is due to increased levels of circulating lipids, we measured total serum cholesterol and triglyceride at 17 and 34 weeks of age in these animals. Despite having increased aortic lipid accumulation, apoE/FcγRIIb−/− male mice have similar levels of serum triglyceride and cholesterol as their apoE−/− littermates at 17 weeks of age (Figure 1D), and at 34 weeks of age (data not shown). We did not observe differences in triglyceride and cholesterol levels in female mice (data not shown), indicating that differences in atherosclerosis between males and females are not due to differences in circulating lipid levels. Moreover, this finding suggests that the increased atherosclerosis observed in male apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice is related to dysregulation of the immune compartment.

Lesion composition in apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice

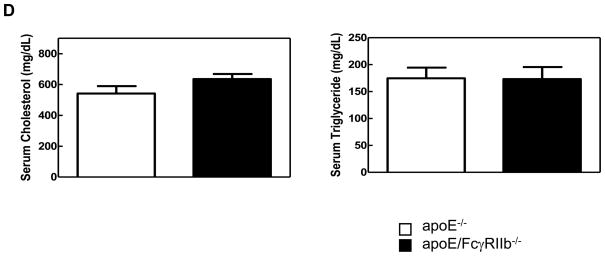

To determine if absence of the FcγRIIb changes the cellular composition of the atherosclerotic lesion, we obtained RNA from the atherosclerotic lesions by LCM and amplified the cDNA using primers specific for the macrophage marker CD68, the chemokine MCP-1, which attracts macrophages, and the T cell marker CD3. After normalization against 18S cDNA, we observed marked increases in expression of CD3 in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice at 17 weeks of age; CD3 mRNA in lesions of apoE−/− mice were negligible at this age making statistical comparison difficult (Figure 2A). Although these data did not reach statistical significance, they may suggest that the inhibitory FcγRIIb influences the inflammatory environment of the aorta either by affecting migration or the activation of T cells. We found no difference in the expression of CD68, and non-significant increase increased expression of MCP-1 at 34 weeks of age in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Cellular infiltration of atherosclerotic lesions in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice.

cDNA from atherosclerotic lesions from apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− male mice was amplified for detection of CD68, MCP-1 and CD3 expression. A) 17 week old mice. B) 34 week old mice. Data is representative of at least 3 mice per group.

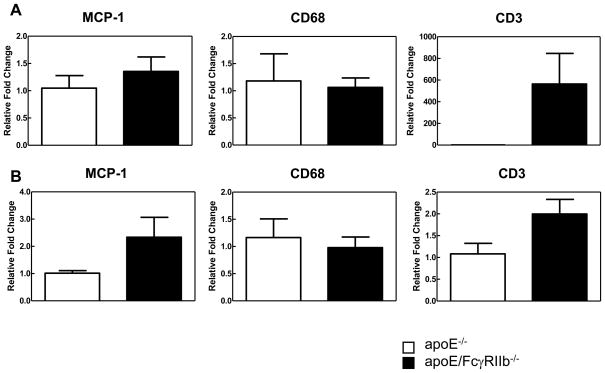

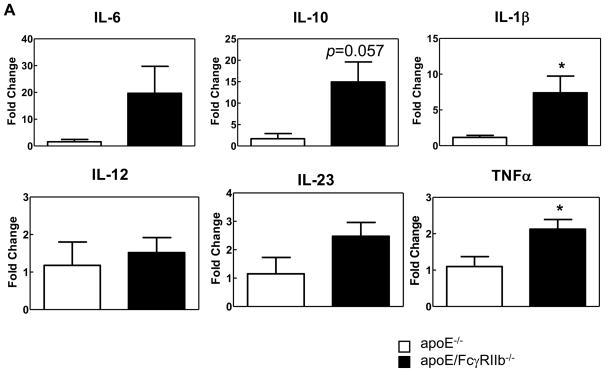

Increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in aortic lesions of apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice

Next, we tested the hypothesis that FcγRIIb is important in regulating inflammatory responses during hyperlipidemia by measuring the cytokine environment in the aortic lesions of apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice by LCM. At 17 weeks-of-age, we did not observe significant differences in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (data not shown). However, at 34 weeks-of-age, double knockout mice have increased expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, IL-23 and TNFα (Figure 3A). Of these, only IL-1β and TNFα reached statistical significance. Surprisingly, apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice also have increased expression of the atheroprotective cytokine IL-10, which could be a compensatory mechanism to counteract excessive inflammation.

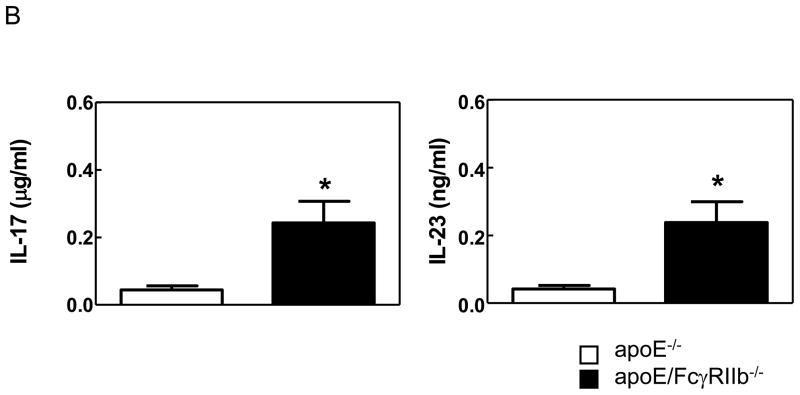

Figure 3. apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice have increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the aorta.

A) Lesions from 34 week-old mice were microdissected, mRNA was isolated and cDNA subjected to RT-PCR. Data is representative of 2–4 mice per group. * p<0.05 by Student’s t test. B) Secretion of IL-17A and IL-23 (p19/p40) in culture supernatants from unstimulated cultured aortas from age-matched apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− male mice was measured by ELISA. n ≥ 5 * p<0.05 by Student’s t test.

The presence of increased cytokine mRNA levels in lesions at 34 weeks-of-age suggest that the absence of FcγRIIb expression in apoE−/− mice results in a change in the chronic inflammatory environment in the aorta that may lead to sustained immune response to hyperlipidemia. Because it is well established that IL-17A plays a pathogenic role in a variety of chronic inflammatory diseases, including atherosclerosis27, 28, we further tested the role of FcγRIIb in downregulating inflammation by measuring the levels of IL-17A and IL-23 (a cytokine necessary for the induction of IL-17 responses) in unstimulated aortic cultures from apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that apoE/FcγRIIb−/− secrete significantly higher levels of IL-17A and IL-23 in the aorta (Figure 3B). Secretion of IL-17A in splenocyte cultures was not different between apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice, indicating that inflammatory responses may be localized to the aorta (data not shown). Our cytokine analysis indicates that the inhibitory FcγRIIb plays a role in regulating the immune response in atherosclerosis by perhaps dampening chronic pro-inflammatory responses in the aorta.

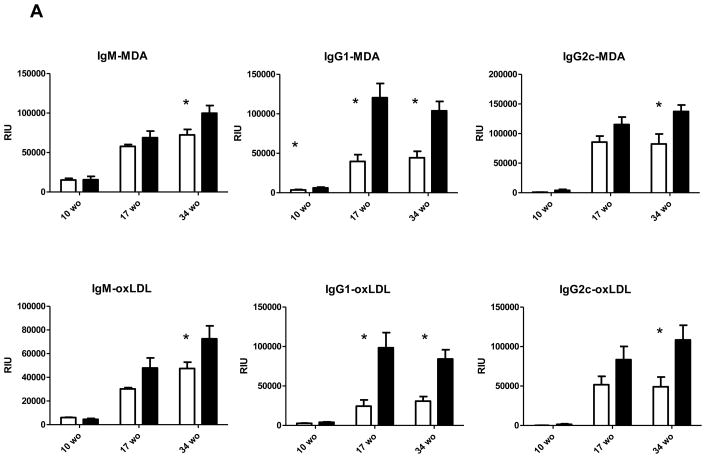

Increased B cell responses to modified LDL in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice

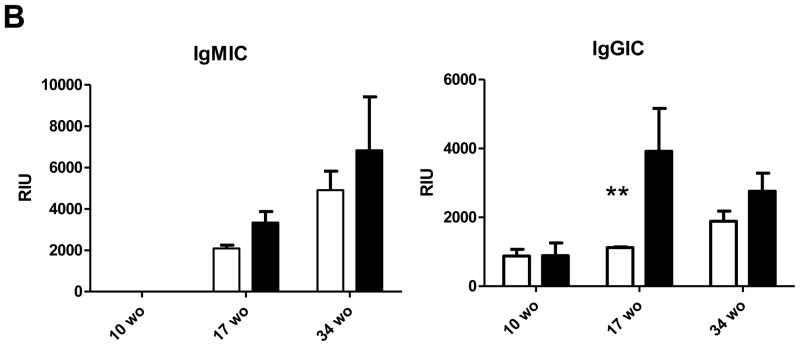

Because we did not detect any major significant differences in lipid levels between apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice, we hypothesized that the accelerated cardiovascular disease in the absence of FcγRIIb was due to functional differences in the immune compartment. Since B cell activation is regulated by the FcγRIIb 29, we determined whether absence of the inhibitory receptor affected the antibody response to modified LDL. We measured IgM, IgG1 and IgG2c titers to malondialdehyde-modified LDL (MDA) and Cu2+-oxidized LDL in the serum of 17 and 34 week old male apoE−/− and apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice. At 10 and 17 weeks-of-age, we observed significant increases in only the IgG1 isotype indicating skewed Th2 adaptive immune responses in the apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice (Figure 4A). There were no differences in IgM titers at these early time points. At 34 weeks-of-age we observed a significant increase in titers to both MDA-modified LDL and oxidized LDL (Figure 4A). We also measured serum titers of the specific IgM natural antibody E06/T15 that binds phosphocholine epitopes of oxidized phospholipids 30, but did not find differences between the two mice models at any of the time points (data not shown).

Figure 4. Increased B cell responses to modified LDL in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice.

A) Serum was analyzed for the presence of IgM, IgG1 and IgG2c binding to malondialdehyde (MDA)-modified LDL or Cu2+ oxidized LDL by chemiluminescent immunoassay as described in Methods. Dilutions for the respective measurements were: IgM 1:800, IgG1 and IgG2c 1:100 and Immune complexes 1:100. B) IgM immune complexes (IGMIC) and IgG immune complexes (IgGIC) were measured at 1:100 dilution. n=at least three mice per group. *p<0.05 using a Student’s t test.

Similar to IgG1 titers, absence of FcγRIIb significantly altered the levels of serum IgG immune complexes (IC) to modified LDL at 17 weeks-of-age (Figure 4B). There were no differences in IgM IC at any age. Overall, our results indicate that the FcγRIIb is important in downregulating the B cell response to modified LDL during hyperlipidemia; more specifically, the adaptive B cell response reflected in increased IgG1 and IgG-oxLDL IC. These changes in antibody titers to modified LDL were observed in the absence of any specific changes in the proportion of splenic B cells or T cells (data not shown).

Discussion

Antibody responses to modified LDL are a significant component of atherosclerotic lesions. It has been suggested that such modified LDL-IC could play an atheroprotective role through the interaction with the inhibitory FcγRIIb. In vivo, it has been demonstrated that the activating isoforms of FcγR contribute to lesion formation 23, 24 and more recently, that the inhibitory FcγRIIb was atheroprotective in LDLr−/− mice that received FcγRIIb-deficient bone marrow 25. Here we demonstrate that the FcγRIIb is also atheroprotective in apoE−/− mice but, in contrast to the previous study in LDLr−/− mice, our data demonstrate that only the males develop exacerbated atherosclerosis. It is not clear why there should be such a gender bias, but it is known that estrogens can have differential effects on the immune system, which can obviously affect atherogenesis. Interestingly, this gender-specific effect on atherosclerosis has been demonstrated in IFN-γ-deficient apoE−/− mice as well,31 and therefore gender is an important consideration when conducting these types of investigations.

Consistent with previous findings 25, we observed an increased antibody response to modified and oxLDL. However unlike Zhao et al, 25 who reported an increase in IgG2c antibody responses, we saw skewing toward a switch to IgG1 production at 10 and 17 weeks-of-age. The discrepancy in our study and that of Zhao et al may be due to the strain of mice or the time of observation. Zhao et al 25 analyzed LDLr−/− that were on diet for 24 weeks and indeed, in our older apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice we saw increases in all Ig isotypes. In addition, we observed significantly increased titers of IgG IC to modified LDL at 17 weeks of age in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice compared to apoE−/− controls. Interestingly, the increase in IgG IC and IgG1 titers at 17 weeks-of-age corresponds to the age where the difference in atherosclerotic lesions in the male apoE/FcγRIIb−/− is most prominent (Figure 1). These data are compelling as it has been thought for some time that not all Ig is created equal when it comes to protection against atherosclerosis. More specifically, there is a large body of work that indicates that natural antibody (i.e. E06 and IgM) is the most protective form, blocking uptake of modified LDL by macrophages and eliminating lipoproteins through receptors other than Fcγ 32, 33. Conversely, IgG may be pro-atherogenic as it can easily bind the activating FcγRs, sustaining inflammation. It is interesting that in the absence of FcγRIIb, oxLDL specific IgG1, the isotype that binds with the highest affinity to this receptor 34, accumulates much earlier in the apoE/FcγIIb−/− mice compared to control. In addition, recent studies by Ait-Oufella, et al 35, demonstrated that B cells and IgG isotype antibodies can have pathogenic qualities in the context of atherogenesis. Therefore, these results underscore the importance of the FcγRIIb in regulating B cell activation and suggest that adaptive B cell responses to modified lipoprotein, in the absence of the down-modulatory FcγRIIb may contribute to atherogenesis.

Based on our findings, we consider several mechanisms through which FcγRIIb can confer protection against atherosclerosis. Since FcγRIIb has an important role in down regulation of B cell activation, proliferation and survival, one possibility is that early antibody responses to LDL prevent the generation of long-lived plasma cells that can contribute to the perpetuation of inflammation by conveying negative signals through the FcγRIIb. Another possibility is that antibodies to minimally-modified LDL down modulate the B cell responses to extensively-modified LDL via the FcγRIIb.

The FcγRIIb can also modulate atherogenesis by regulating activating FcγR signaling on antigen presenting cells, specifically dendritic cells. Dendritic cells express both activating and inhibitory FcγRs and have the unique capacity to polarize T cell responses. Here we show that apoE/FcγRIIb−/− develop a pro-inflammatory cytokine environment in the aorta that is characterized by increased levels of expression of the immunopathogenic cytokine IL-17A. The importance of IL-17A responses in atherosclerosis has emerged from studies performed only in the past two years. In humans, IL-17-secreting cells are a major component of human atherosclerotic plaques 36, 37, and patients with acute coronary syndrome present a Th17/Treg imbalance, characterized by an increase in IL-17 producing Th17 cells and a decrease in Treg numbers 38. In hypercholesterolemic mice, disruption of the IL-17 pathway results in decreased atherosclerosis 27, 28, and atherogenesis in apoE−/− mice is characterized by a Th17/Treg imbalance 39. On the other hand, studies by Mallat’s group have shown that B-cell depletion reduces atherosclerosis and that this reduction is accompanied by an increase in IL-17A. Furthermore, IL-17A neutralization abrogated the effect of B cell depletion in reducing atherosclerosis 35. Although our data do not demonstrate a Th17/Treg imbalance in apoE/FcγRIIb−/− mice, our observation suggests that a bias toward a Th17 response could be responsible for increased lesion size in our model. Thus, the role of FcγRIIb in regulating dendritic cell function by preventing Th17 polarization and pathogenic B cell responses in atherosclerosis merits further study.

In conclusion, we have shown that deletion of the inhibitory FcγRIIb results in dysregulation of the B cell compartment and exacerbated atherosclerosis that is characterized by pro-inflammatory cytokine response in the aorta. Our study provides evidence to support the hypothesis that antibodies against modified LDL may protect against atherosclerosis by conveying inhibitory signals through the FcγRIIb that downregulate pro-inflammatory signaling via other immune receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Curtis L. Gabriel for careful revision of this manuscript.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Irvington Institute Fellowship Program of the Cancer Research Institute (Y.V.M.F), NIH NRSA 5T32HL07751 Training Grant in Mechanisms of Vascular Disease (to N.A.B.), and NIH grant R01HL088364 and R01HL089310 (to A.S.M.) and R01 HL086559 and HL088093 (CJ.D;J.L.W).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors do not have any financial conflicts to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hansson GK, Libby P, Schonbeck U, Yan ZQ. Innate and adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2002;91:281–291. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000029784.15893.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galkina E, Kadl A, Sanders J, Varughese D, Sarembock IJ, Ley K. Lymphocyte recruitment into the aortic wall before and during development of atherosclerosis is partially L-selectin dependent. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1273–1282. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis. the road ahead. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson GK, Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:508–519. doi: 10.1038/nri1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reardon CA, Blachowicz L, White T, Cabana V, Wang Y, Lukens J, Bluestone J, Getz GS. Effect of immune deficiency on lipoproteins and atherosclerosis in male apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1011–1016. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caligiuri G, Nicoletti A, Poirier B, Hansson GK. Protective immunity against atherosclerosis carried by B cells of hypercholesterolemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:745–753. doi: 10.1172/JCI07272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Major AS, Fazio S, Linton MF. B-lymphocyte deficiency increases atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1892–1898. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000039169.47943.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binder CJ, Horkko S, Dewan A, Chang MK, Kieu EP, Goodyear CS, Shaw PX, Palinski W, Witztum JL, Silverman GJ. Pneumococcal vaccination decreases atherosclerotic lesion formation: molecular mimicry between Streptococcus pneumoniae and oxidized LDL. Nat Med. 2003;9:736–743. doi: 10.1038/nm876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ameli S, Hultgardh-Nilsson A, Regnstrom J, Calara F, Yano J, Cercek B, Shah PK, Nilsson J. Effect of immunization with homologous LDL and oxidized LDL on early atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:1074–1079. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palinski W, Miller E, Witztum JL. Immunization of low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-deficient rabbits with homologous malondialdehyde-modified LDL reduces atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:821–825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou X, Caligiuri G, Hamsten A, Lefvert AK, Hansson GK. LDL immunization induces T-cell-dependent antibody formation and protection against atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:108–114. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiopu A, Bengtsson J, Soderberg I, Janciauskiene S, Lindgren S, Ares MP, Shah PK, Carlsson R, Nilsson J, Fredrikson GN. Recombinant human antibodies against aldehyde-modified apolipoprotein B-100 peptide sequences inhibit atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;110:2047–2052. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143162.56057.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fc-receptors as regulators of immunity. Adv Immunol. 2007;96:179–204. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(07)96005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nimmerjahn F, Bruhns P, Horiuchi K, Ravetch JV. FcgammaRIV: a novel FcR with distinct IgG subclass specificity. Immunity. 2005;23:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ratcliffe NR, Kennedy SM, Morganelli PM. Immunocytochemical detection of Fcgamma receptors in human atherosclerotic lesions. Immunol Lett. 2001;77:169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan Z, Kishimoto C, Sano H, Shioji K, Xu Y, Yokode M. Immunoglobulin treatment suppresses atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice via the Fc portion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H899–906. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00926.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raaz D, Herrmann M, Ekici AB, Klinghammer L, Lausen B, Voll RE, Leusen JH, van de Winkel JG, Daniel WG, Reis A, Garlichs CD. FcgammaRIIa genotype is associated with acute coronary syndromes as first manifestation of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calverley DC, Varteresian T, Brass E, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S, Mack WJ, Buchanan TA, Hodis HN, Schreiber AD. Association between monocyte Fcgamma subclass expression and acute coronary syndrome. Immun Ageing. 2004;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y, Jaffa A, Koskinen S, Takei A, Lopes-Virella MF. Oxidized LDL-containing immune complexes induce Fc gamma receptor I-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in THP-1 macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1600–1607. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.7.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Y, Fleming AJ, Wu S, Virella G, Lopes-Virella MF. Fc-gamma receptor cross-linking by immune complexes induces matrix metalloproteinase-1 in U937 cells via mitogen-activated protein kinase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2533–2538. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gisinger C, Virella GT, Lopes-Virella MF. Erythrocyte-bound low-density lipoprotein immune complexes lead to cholesteryl ester accumulation in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;59:37–52. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(91)90080-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morganelli PM, Rogers RA, Kitzmiller TJ, Bergeron A. Enhanced metabolism of LDL aggregates mediated by specific human monocyte IgG Fc receptors. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:714–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly JA, Griffin ME, Fava RA, Wood SG, Bessette KA, Miller ER, Huber SA, Binder CJ, Witztum JL, Morganelli PM. Inhibition of arterial lesion progression in CD16-deficient mice: evidence for altered immunity and the role of IL-10. Cardiovasc Res. 85:224–231. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez-Vargas P, Ortiz-Munoz G, Lopez-Franco O, Suzuki Y, Gallego-Delgado J, Sanjuan G, Lazaro A, Lopez-Parra V, Ortega L, Egido J, Gomez-Guerrero C. Fcgamma receptor deficiency confers protection against atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Circ Res. 2006;99:1188–1196. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250556.07796.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao M, Wigren M, Duner P, Kolbus D, Olofsson KE, Bjorkbacka H, Nilsson J, Fredrikson GN. FcgammaRIIB inhibits the development of atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. J Immunol. 184:2253–2260. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takai T, Ono M, Hikida M, Ohmori H, Ravetch JV. Augmented humoral and anaphylactic responses in Fc gamma RII-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;379:346–349. doi: 10.1038/379346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erbel C, Chen L, Bea F, Wangler S, Celik S, Lasitschka F, Wang Y, Bockler D, Katus HA, Dengler TJ. Inhibition of IL-17A attenuates atherosclerotic lesion development in apoE-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2009;183:8167–8175. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Es T, van Puijvelde GH, Ramos OH, Segers FM, Joosten LA, van den Berg WB, Michon IM, de Vos P, van Berkel TJ, Kuiper J. Attenuated atherosclerosis upon IL-17R signaling disruption in LDLr deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;388:261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravetch JV, Bolland S. IgG Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:275–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw PX, Horkko S, Chang MK, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Silverman GJ, Witztum JL. Natural antibodies with the T15 idiotype may act in atherosclerosis, apoptotic clearance, and protective immunity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1731–1740. doi: 10.1172/JCI8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitman SC, Ravisankar P, Daugherty A. IFN-gamma deficiency exerts gender-specific effects on atherogenesis in apolipoprotein E−/− mice. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:661–670. doi: 10.1089/10799900260100141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horkko S, Bird DA, Miller E, Itabe H, Leitinger N, Subbanagounder G, Berliner JA, Friedman P, Dennis EA, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Witztum JL. Monoclonal autoantibodies specific for oxidized phospholipids or oxidized phospholipid-protein adducts inhibit macrophage uptake of oxidized low-density lipoproteins. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:117–128. doi: 10.1172/JCI4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobayashi K, Tada K, Itabe H, Ueno T, Liu PH, Tsutsumi A, Kuwana M, Yasuda T, Shoenfeld Y, de Groot PG, Matsuura E. Distinguished effects of antiphospholipid antibodies and anti-oxidized LDL antibodies on oxidized LDL uptake by macrophages. Lupus. 2007;16:929–938. doi: 10.1177/0961203307084170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Unkeless JC. Function and heterogeneity of human Fc receptors for immunoglobulin G. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:355–361. doi: 10.1172/JCI113891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ait-Oufella H, Herbin O, Bouaziz JD, Binder CJ, Uyttenhove C, Laurans L, Taleb S, Van Vre E, Esposito B, Vilar J, Sirvent J, Van Snick J, Tedgui A, Tedder TF, Mallat Z. B cell depletion reduces the development of atherosclerosis in mice. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1579–1587. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eid RE, Rao DA, Zhou J, Lo SF, Ranjbaran H, Gallo A, Sokol SI, Pfau S, Pober JS, Tellides G. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma are produced concomitantly by human coronary artery-infiltrating T cells and act synergistically on vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2009;119:1424–1432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Boer OJ, van der Meer JJ, Teeling P, van der Loos CM, Idu MM, van Maldegem F, Aten J, van der Wal AC. Differential expression of interleukin-17 family cytokines in intact and complicated human atherosclerotic plaques. J Pathol. 220:499–508. doi: 10.1002/path.2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng X, Yu X, Ding YJ, Fu QQ, Xie JJ, Tang TT, Yao R, Chen Y, Liao YH. The Th17/Treg imbalance in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2008;127:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie JJ, Wang J, Tang TT, Chen J, Gao XL, Yuan J, Zhou ZH, Liao MY, Yao R, Yu X, Wang D, Cheng Y, Liao YH, Cheng X. The Th17/Treg functional imbalance during atherogenesis in ApoE(−/−) mice. Cytokine. 49:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]