Abstract

Objective

The present study evaluated the smooth muscle functional response and viability of human saphenous vein (HSV) grafts after harvest, and explored the effect of mechanical stretch on contractile responses of porcine saphenous vein (PSV).

Design of study

The contractile responses (stress, 105N/m2) of de-identified, remnant HSV grafts to depolarizing potassium chloride and the agonist norepinephrine was measured in a muscle organ bath. Cellular viability was evaluated using a methylthiazol tetrazolium (MTT) assay. A PSV model was used to evaluate the effect of radial, longitudinal and angular stretch on smooth muscle contractile responses.

Results

Contractile responses varied greatly in HSV harvested for autologous vascular and coronary bypass procedures (0.04198×105 N/m2 ± 0.008128 to 0.1192×105N/m2 ± 0.02776). Contractility of the HSV correlated with the cellular viability of the grafts. In the PSV model, manual radial distension of ≥300mmHg had no impact on the smooth muscle responses of PSV to potassium chloride. Longitudinal and angular stretch significantly decreased the contractile function of PSV by 33.16% and 15.26%, respectively.

Conclusions

There is considerable variability in HSV harvested for use as an autologous conduit. Longitudinal and angular stretching during surgical harvest impair contractile responsiveness of the smooth muscle in saphenous vein. Avoiding stretch-induced injuries to the conduits during harvest and preparation for implantation may reduce adverse biologic responses in the graft (e.g. intimal hyperplasia) and improve patency of autologous vein graft bypasses.

Keywords: saphenous vein graft, smooth muscle, mechanical stretch

Introduction

Human saphenous vein (HSV) continues to be the most commonly used conduit for autologous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and peripheral vascular (PV) surgery (1). Failure of the vein grafts remains a major limitation of these procedures. The per patient vein graft failure rate in 1,920 patients at 12-18 months in the PREVENT-IV trial was 45% (2). Intimal hyperplasia, a ‘response to injury,’ remains the leading cause of vein graft failure. While the precise mechanism is not completely understood, Intimal hyperplasia results from a cascade of molecular and cellular events that are triggered by injury. Intimal hyperplasia is a complex process involving vascular smooth muscle proliferation, migration, phenotypic modulation of the smooth muscle cells from a contractile to a synthetic phenotype, and extracellular matrix production (3, 4). Intimal hyperplasia will develop to varying degrees in the vein graft after its insertion into the arterial circulation (5). In general, Intimal hyperplasia is a self-limiting process, however, in focal areas, it can lead to significant lumen compromise (6-8). The focal area of stenoses, are usually located at sites of conduit abnormalities or of unrepaired defects (8). This process leads to pathologic narrowing of the vessel lumen, graft stenoses, and ultimately graft failure (9).

The morphologic integrity of the vein graft conduit and its integrity prior to implantation as a graft are important for the long-term patency of the graft itself. Therefore, harvesting and handling of the conduit play a significant role in the patency of vein grafts (10). While the impact of endothelial injury has been the subject of numerous investigations, few studies have evaluated smooth muscle functional viability of the vein graft. Vascular smooth muscle is the contractile component of veins and arteries and the control of relaxation and contraction is dependent upon exposure to both intrinsic (e.g. nitric oxide, metabolic changes) and extrinsic (e.g. environmental stressors) stimuli. Integration of these signals is reflected in the modulation of intracellular calcium and cGMP that are fundamentally important in determining vascular reactivity, smooth muscle proliferation and phenotype of the tissues. Physiological adaptation is one of the critical attributes of early vein graft remodeling. The vein tunica media consists predominantly of smooth muscle cells that oriented both longitudinally and circumferentially whereas arterial orientation is longitudinal and spiral, a manner better suited to conduct the arterial pulse. Saphenous vein has an active myogenic response contracting to acute increases in luminal pressure, a unique property which allows it to respond to rapid changes in pressure when a person moves from recumbent to standing position (11). With exposure to arterial flow, this reflex is enhanced if not sustained with an increased sensitivity to phenylephrine and catecholamine leading to increased tension in smooth muscle (12, 13). Taken together, smooth muscle viability and function is important for optimal adaptation into the arterial circulation.

The present study aims at evaluating the contractile responsiveness of smooth muscle in vein grafts harvested for coronary and peripheral reconstructions. We also employed a porcine saphenous vein (PSV) model and study the impact of intraoperative manipulation on smooth muscle function. We hypothesized that stretch-induced injuries incurred during vein harvest reduce smooth muscle functional viability of the conduits.

Methods

Material and reagents

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless specified otherwise.

Procurement of Human Saphenous Vein (HSV)

Sixty (60) de-identified remnants of HSV were collected from patients undergoing CABG and PV surgery after approval of the Institutional Review Boards of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, TN. The HSV were harvested by either open or minimally invasive endoscopic technique according to the discretion of the surgeons. The HSV were stored in heparinized saline solution until the end of the surgical procedure at which time they were placed in cold University of Wisconsin (UW) transplant harvest buffer [100 mM potassium lactobionate, 25 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM MgSO4, 30 mM raffinose, 5 mM adenosine, 3 mM glutathione, 1 mM allopurinol, 50g/L hydroxyethyl starch (Cell Preservation Solutions, Adelphia, NJ), pH 7.4] at 4°C. The HSV were tested within 24 hours of harvest. UW organ transplant solution has been shown to preserve viability of HSV for up to 48 hrs without significant loss to vasoreactivity (14). Upon gross inspection of the segments, regions of the grafts that were damaged by forceps or clamps were discarded. Only regions that were without damage or branches were used for analysis.

All animal procedures followed institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. The study protocol was approved by Vanderbilt Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) Porcine saphenous veins from euthanized pigs were dissected using an open harvest ‘no touch’ technique and placed in UW transplant harvest buffer at 4°C and tested within 24 hours of harvest.

Physiological measurements of smooth muscle function

One-millimeter rings were cut from segments of HSV and dissected free of fat and connective tissue. The rings were weighed and their lengths recorded. In order to focus on smooth muscle responses, the endothelium was mechanically denuded by gently rolling the luminal surface of each ring at the tip of a fine vascular forceps (15) before suspension in a muscle bath containing a bicarbonate buffer (120 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgSO4, 1.0 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM glucose, 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 25 mM Na2HCO3, pH 7.4), equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37°C. Rings were progressively stretched to its optimal resting tension (approximately 1 gm) that would produce a maximal response to contractile agonists as determined previously (16, 17). The rings were stretched to 4 g of tension and then maintained at the resting tension and equilibrated for a minimum of 2hr. Force measurements were obtained using a Radnoti Glass Technology (Monrovia, CA) force transducer (159901A) interfaced with a Powerlab data acquisition system and Chart software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO). We first characterized smooth muscle functional viability in response to a potassium challenge, which causes depolarization of the membrane leading to contraction of functionally viable smooth muscle (18). HSV rings were contracted repeatedly with 110 mM KCl (with equimolar replacement of NaCl in bicarbonate buffer) until maximal response is generated. Tissues that failed to respond to KCl were not tested further. Rings that generated a stress meeting our defined criteria for viability were washed to remove the KCl and equilibrated in the bicarbonate solution for 30 minutes. Contractile response of saphenous vein rings to a physiologic agonist, norepinephrine (NE; 10-6 to 10-7M), was then tested.

Cellular Viability Assay

To quantitate cellular viability, a modified methylthiazol tetrazolium (MTT) assay was used (19). In this colormetric assay, MTT is reduced by a mitochondrial enzyme in living cells to an insoluble purple product, formazan. The resulting product is then extracted from the tissues with a solvent and measured spectrophotometrically. Briefly, four separate rings were cut from each HSV (n=13). These fresh rings were not subjected to any muscle bath equilibration or vasocontractility testing. One ring was placed in water and microwaved for ten minutes to serve as a control. Each ring was placed in 250 microliters of 0.1% (1 mg/mL) MTT in phosphate buffered saline and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. The reaction was stopped by transferring the rings into distilled water, each ring was blotted dry and weighed. The rings were then placed in 1 mL of CelloSolve (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) solution for 4 hr at 37°C to extract the resulting pigment from the tissues. The concentration of the pigments was measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm. The viability index was expressed as OD570/mg/mL.

Mechanical stretch of Porcine Saphenous Vein (PSV)

We evaluated the intraoperative mechanical handling maneuvers that may cause injury to saphenous veins. PSV were subjected to one of the following: distension, longitudinal stretch, or angular stretch. To distend the veins, PSV (n=4) was cannulated proximally and distally with a bullet tip needle (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN), secured with a 4-0 silk suture. Pressure was measured at the distal end with a manometer with maximum measurement capacity of 300 mmHg. Heparinized saline in a syringe was then injected at a pressure of exceeding 300mmHg for 2 min. To perform longitudinal stretch injury, PSV (n=4) was secured at each end with a clamp, stretched to 200% of original length and held in the position for fifteen seconds. This was repeated three times. Angular stretch was performed by securing each end of the PSV (n=4) between two fixed points, and the PSV was lifted upward with a right angle clamp until maximum resistance was met. This position was maintained for fifteen seconds. This was repeated three times. Rings of 1mm width were cut and the endothelium denuded. Functional viability of the tissues was tested as described for HSV.

Data analysis

Contractile response was defined by stress, which was calculated using the force generated by the tissues. Stress [105Newtons (N)/m2] = force (g) × 0.0987 / area, where area is equal to the wet weight [(mg) / length (mm at maximal length)] divided by 1.055) (20) and force is the maximum tension generated in response to high KCl challenge. Any tissue that generated stress of 0.025×105N/m2 or greater was considered functionally viable, which correlates to 0.5 g of force for a 10 mg, 1mm thick, 4mm diameter ring. Data was reported as mean responses ±standard error of the mean. Unpaired t-tests were conducted in order to determine the significance (p value) of each experiment. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Variable smooth muscle contractile response of HSV

Sixty (60) de-identified HSV were collected. We mechanically removed the endothelium to focus on smooth muscle-derived function. Denudation of the endothelium was confirmed by exposure to acetylcholine (5×10-7M) of NE-precontracted segment from randomly selected HSV (15). In all case, no relaxation was observed suggesting that the endothelium was reliably denuded (data not shown).

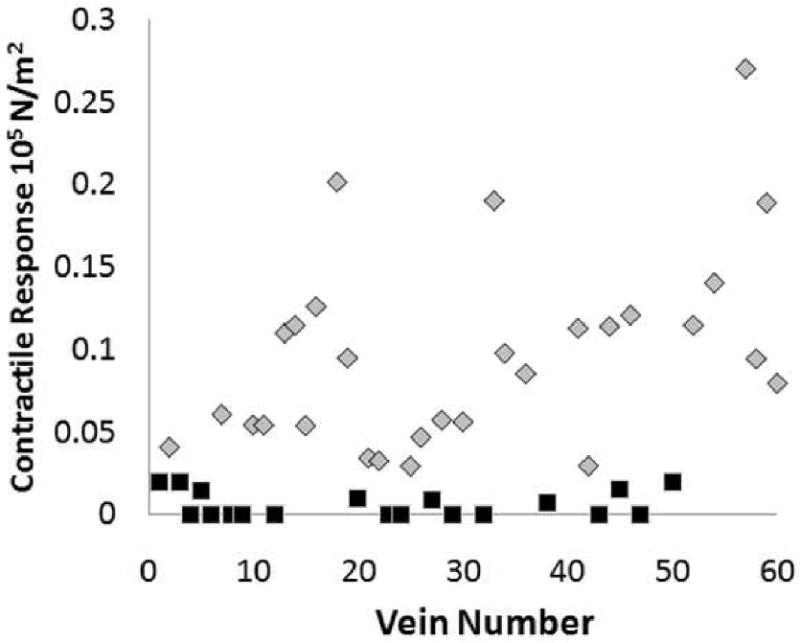

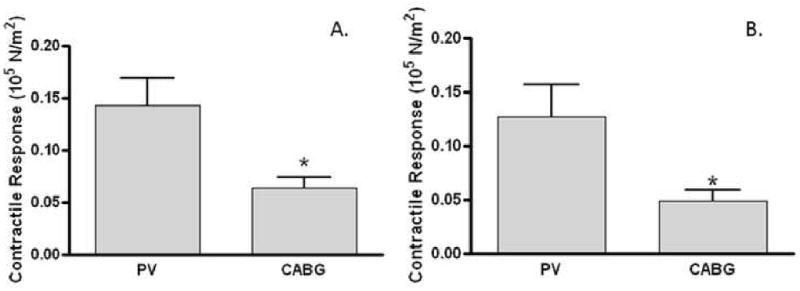

We first characterized smooth muscle contractile function in response to a depolarizing potassium challenge. Smooth muscle functional viability varied greatly in the HSV used for vascular reconstruction (Figure 1). Approximately 33% of the HSV segments were functionally non-viable with 11 veins failing to generate any contractile response to the potassium challenge. A significant difference in smooth muscle function was also observed (Figure 2) when the HSV graft segments harvested for CABG were compared to those harvested for PV. CABG veins generated significantly (P=<0.05) lower stress to KCl (0.06412 ±0.01037 105N/m2, n=26) than PV veins (0.1433 ±0.02550 105N/m2, n=12). There was a 55.25% reduction in smooth muscle functional viability in the CABG veins (Figure 2A) compared to the peripheral veins.

Figure 1. Smooth muscle contractile responsiveness varied greatly in remnant saphenous vein grafts.

Remnant saphenous vein (n=60) from patients undergoing coronary artery bypass or peripheral vascular revascularization surgery were collected. Rings from each vein were suspended in a muscle bath, contracted with KCl (110 mM), force was measured and converted to stress (105N/m2). Each data point represented a vein graft from a different patient and 3 segments were tested from each patient and averaged. Veins generated stress of ≤0.025×105N/m2 were considered non-viable (black) and those generated stress of >0.025×105N/m2 were viable (grey).

Figure 2. Contractile response differed in remnant human saphenous vein grafts.

Vein segments (n=38) obtained from patients undergoing either perivascular vein reconstruction (PV) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) procedures were suspended in a muscle bath, contracted with 110mM KCl (A) or 10-6 to 10-7 M norepinephrine (B), force was measured and converted to stress (105N/m2). At least 3 segments were tested from each patient and averaged. Data represented averaged stress generated by the HSV collected from each group. *p<0.05.

HSV that generated stress of ≥0.025×105 N/m2 in response to 110mM KCl were considered functionally viable. This parameter was chosen as HSV producing lower stress could not be used effectively to measure agonists or antagonists induced contractile functions. Viable rings were further tested for their response to the agonist norepinephrine (NE; Figure 2B). CABG veins generated significantly lower stress to NE (0.04950 ±0.009791 105N/m2, n=23) than PV veins (0.1271 ±0.02959 105 N/m2, n=10). There was a 61.05% reduction in contractile response to NE in CABG veins as compared to that generated in PV veins (Figure 2B), a similar extent seen with the KCl depolarization response.

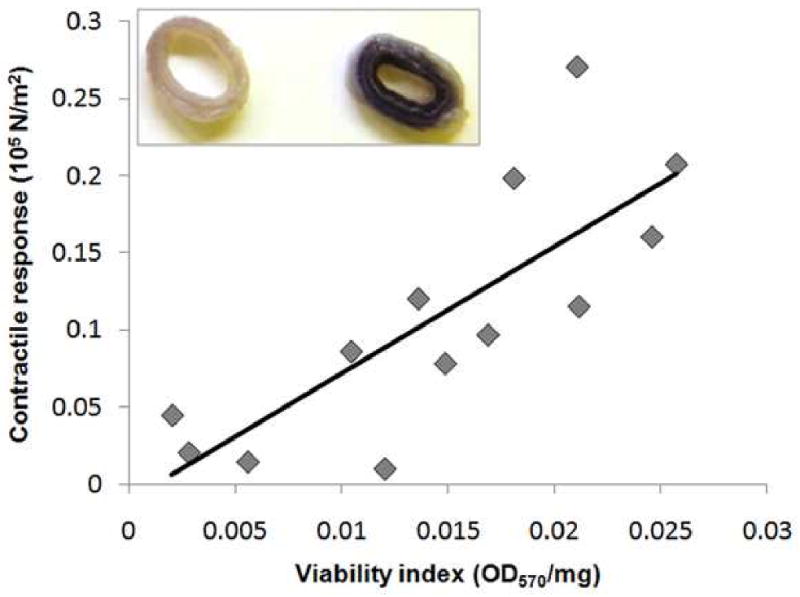

Functional response correlated with cellular viability in HSV

We used a MTT assay to determine if the lack of contractile response in HSV correlated with viability of saphenous vein smooth muscle at the cellular level. Smooth muscle function directly correlated with cellular viability in HSV (Figure 3), implicating that the smooth muscle cells were not viable in the HSV that failed to generate a contractile response. Whenever possible, viability of multiple regions of the grafts was assessed and no significant difference was observed along the length of the graft segment in the MTT index (data not shown). The loss of cellular viability and contractility may potentially result from injury during harvest and graft preparation prior to implantation.

Figure 3. Functional response (contractile response to KCl) correlated with cell viability in human saphenous vein grafts.

Remnant human saphenous vein (n=13) were suspended in a muscle bath, contracted with KCl (110 mM), force measured and stress was calculated. Cell viability was determined in other sections of the same veins using methylthiazol tetrazolium (MTT). The purple precipitate was measured spectrophotometrically (R2= 0.7262). Inset, representative HSV rings of low (left) and high (right) viability index.

Mechanical stretch reduced PSV smooth muscle function viability

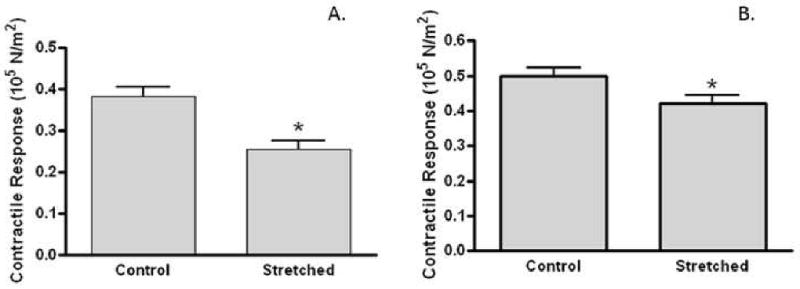

We use a PSV model to evaluate the intraoperative mechanical handling maneuvers that may cause injury to HSV at the time of harvest and prior to implantation. We used PSV which is of similar caliber as HSV and represents a model system with less variability in function. Distension of PSV to a pressure of >300mmHg did not reduce smooth muscle functional viability (data not shown). When PSV were subjected to longitudinal stretch (Figure 4A), a significantly (P=<0.05) lower stress (0.256 ±0.021 105N/m2, n=4) was generated, as compared to the non-stretched controls (0.383 ±0.023 105 N/m2, n=4). Longitudinal stretching of vein segments reduced smooth muscle functional viability by 33.16%. Angular stretch reduced smooth muscle contractile function in PSV by 15.26% (Figure 4B). PSV subjected to angular stretch generated a significantly (P<0.05) lower stress (0.422 ±0.021 105 N/m2, n=4) than non-stretched controls (0.498 ±0.024 105 N/m2, n=4).

Figure 4. Mechanical stretch injuries reduced contractile response in a porcine saphenous vein model.

Porcine saphenous vein (PSV; n=4) harvested using the “no-touch” technique was subjected to longitudinal (A) or angular (B) stretching. Segments were suspended in a muscle bath, contracted with KCl, force measured and converted to stress (105N/m2) At least 2 segments from each PSV were tested for each treatment and averaged. Data represented averaged stress for each treatment. *p<0.05.

Discussion

In the present study, we assessed physiologic response of remnant human saphenous vein used for autologous vascular reconstructions and showed that the smooth muscle functional viability of the vein grafts varied greatly, with 33% of the HSV examined in this study non responsive to contractile challenges following harvest. We showed that viability at the cellular level, as determined by a MTT assay, directly correlated with the physiologic contractile function measured in muscle bath. Our observation implicates that the viability and hence functional properties of these conduits were compromised at the time of harvest or during graft preparation for implantation.

Vein graft patency of CABG surgery is limited by the development of occlusive Intimal hyperplasia. A number of drugs that have been tested in clinical trials to prevent Intimal hyperplasia have failed. Anti-thrombotic and anti-platelet agents such as warfarin, clopidogrel, and aspirin, have little or no effect on Intimal hyperplasia (21). Drug eluting stents have been shown to be effective in preventing restenosis after coronary angioplasty, however, there is no therapeutic currently approved for autologous conduits. Two large clinical trials for the prevention of coronary and peripheral vascular vein graft failure using an E2F decoy (a short sequence of DNA that binds to transcription factors, sequestering these proteins) to prevent smooth muscle proliferation failed in their primary endpoint (2, 22). Results from a canine model showed that vein grafts prepared by an optimal technique, which involves minimal mechanical manipulation, minimizes endothelial and medial injury (9). In spite of this, current surgical practices continue to cause injury in vein grafts. Since Intimal hyperplasia is a “response to injury” and that surgical harvesting of the vein results in mechanical injury, it follows that ameliorating injury to vein graft prior to implantation will enhance vein graft patency.

We sought to identify which mechanical manipulations associated with surgical harvest that impair vein graft function. The forces imposed on a vein during harvest including shear stress, radial and longitudinal deformation, all of which may stretch the medial layer and damage contractile elements. Manual, uncontrolled distension of harvested veins is a common practice in coronary and peripheral vascular bypass surgery in the operating room to reverse vasospasm and to ligate side branches before final implantation. The distension pressure exceeds 300 mmHg, as measured in our laboratory (data not shown). Okon et al. reported that while moderate distension (100-300 mmHg) increased contractile response of human saphenous vein graft to phenylephrine and depolarization by KCl, pressure distension at 600mmHg considerably reduced the responses (23). This may be explained partly by the orientation of the smooth muscle cells within the venous medial layer that allows them to naturally vary radial dimensions and adjust capacitance at moderate pressure. When excessive amount of force is exerted on the veins, contractility is abolished possibly due to physical disruption of the vessel. In our porcine model, radial distension did not significantly decrease contractility of the PSV. It is possible that PSV is more recalcitrant to distension pressure of above 300mmHg in our study. Our data further suggest that distension, or radial stretch injury, alone may not explain the loss of smooth muscle viability in vein graft.

The majority of HSV harvested for CABG at our institutions are obtained via minimally invasive techniques using endoscopy. HSV obtained from patients undergoing CABG displayed inferior contractile responsiveness when compared to those collected from patients undergoing peripheral vascular surgery, implicating that technical aspects of endoscopic harvest of the graft may play a role in vascular smooth muscle injury. Although histological examination have shown no difference or significant damage to the structural integrity of the tunica intima, media or adventitia between different harvesting techniques (24-26), our PSV model demonstrated that both longitudinal and angular stretch attenuated contractility of smooth muscle in the conduit. It is possible that stretching of the tissue disrupts junctional organization of the medial layer, causing a breakdown of signal and energy transduction in the smooth muscle (27). Goldman et al. demonstrated the mechanical stretch mediates degradation of α-actin filaments in vascular smooth muscle (28). Mechanical stretch also activates the p38 MAPK (29-31), nitric oxide (32), and reactive oxygen species pathways (31), causes release of ATP (33), activates inflammatory pathways (34, 35), and ultimately potentiates apoptosis and proliferation of smooth muscle cells in the vein grafts. Furthermore, stretch-induced modulation of genes involved in myogenic differentiation, e.g. the smooth muscle α-actin (36), SM-22 (37), and VEGF (38), contributes to the vascular remodeling that underlies pathological complications, such as neointima development and atherosclerosis, of the vein grafts.

The principle finding in our study illustrates the adverse effects of longitudinal and right-angle stretch during harvest on smooth muscle function. Not only are these injuries detrimental to the vasomotor function of the vein grafts, they may be responsible for the responses that initiate the smooth muscle cells to undergo apoptosis, migrate and proliferate, resulting in neointima formation. Taken together, ameliorating these injuries at the time of harvest and graft preparation prior to implantation into the arterial circulation may limit the activation of the cascade of events that lead to intimal hyperplasia. Our findings strongly posit the much needed development for alternatives to preserve smooth muscle viability of the vein graft, hence increasing vein graft patency.

Limitations

The present study used de-identified, discarded tissues and was not designed to gather intra-operative data regarding procurement technique used. It is also limited by the lack of information regarding the region, whether proximal or distal, from which the grafts were harvested and long- term follow-up to infer how smooth muscle viability affects HSV graft patency. Furthermore, patient demographics are not available and may contribute to the variability of the response towards injuries during harvest and explain the susceptibility of injuries in HSV.

Clinical Relevance.

Human greater saphenous vein (HSV) remains the most commonly used conduit for coronary artery bypass grafting and peripheral vascular revascularization. Surgical harvest techniques commonly employed for HSV harvest can produce significant injury to the conduit and elicit exuberant physiologic healing response in the vessel walls, leading to the development of Intimal hyperplasia. Intimal hyperplasia is thought to involve smooth muscle proliferation, migration, phenotypic modulation, extracellular matrix deposition, and ultimately lead to graft occlusion. This study shows that mechanical stretching injures vascular smooth muscle and reduces contractile responsiveness of the saphenous vein. Thus, by understanding how these injuries can be minimized, mortality and costs associated with vein graft failure can be reduced.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH RO1HL70715 and a VA Merit Review to C.M. B. and AHA 10crp2550035 to S.E.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors of this paper do not have any competing interests or affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in, or in financial competition with, the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. All financial and material support for this research and work are clearly identified in the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bonow RO, Bennett S, Casey DE, Jr, Ganiats TG, Hlatky MA, Konstam MA, Lambrew CT, Normand SL, Pina IL, Radford MJ, Smith AL, Stevenson LW, Burke G, Eagle KA, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum J, Masoudi FA, Ritchie JL, Rumsfeld JS, Spertus JA. ACC/AHA Clinical Performance Measures for Adults with Chronic Heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Heart Failure Clinical Performance Measures): endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2005 Sep 20;112(12):1853–87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.170072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander JH, Hafley G, Harrington RA, Peterson ED, Ferguson TB, Jr, Lorenz TJ, Goyal A, Gibson M, Mack MJ, Gennevois D, Califf RM, Kouchoukos NT. Efficacy and safety of edifoligide, an E2F transcription factor decoy, for prevention of vein graft failure following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: PREVENT IV: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005 Nov 16;294(19):2446–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.19.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clowes AW, Reidy MA. Prevention of stenosis after vascular reconstruction: pharmacologic control of Intimal hyperplasia--a review. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13(6):885–91. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.27929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allaire E, Clowes AW. Endothelial cell injury in cardiovascular surgery: the Intimal hyperplastic response. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63(2):582–91. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)01045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox JL, Chiasson DA, Gotlieb AI. Stranger in a strange land: the pathogenesis of saphenous vein graft stenosis with emphasis on structural and functional differences between veins and arteries. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1991 Jul-Aug;34(1):45–68. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(91)90019-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sayers RD, Jones L, Varty K, Allen K, Morgan JD, Bell PR, London NJ. The histopathology of infrainguinal vein graft stenoses. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1993 Jan;7(1):16–20. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(05)80537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkowitz HD, Fox AD, Deaton DH. Reversed vein graft stenosis: early diagnosis and management. J Vasc Surg. 1992 Jan;15(1):130–41. doi: 10.1067/mva.1992.33492. discussion 41-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills JL, Bandyk DF, Gahtan V, Esses GE. The origin of infrainguinal vein graft stenosis: a prospective study based on duplex surveillance. J Vasc Surg. 1995 Jan;21(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70240-7. discussion -5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LoGerfo FW, Quist WC, Cantelmo NL, Haudenschild CC. Integrity of vein grafts as a function of initial Intimal and medial preservation. Circulation. 1983;68(3 Pt 2):II117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conte MS. Technical factors in lower-extremity vein bypass surgery: how can we improve outcomes? Semin Vasc Surg. 2009 Dec;22(4):227–33. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berczi V, Greene AS, Dornyei G, Csengody J, Hodi G, Kadar A, Monos E. Venous myogenic tone: studies in human and canine vessels. Am J Physiol. 1992 Aug;263(2 Pt 2):H315–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park TC, Harker CT, Edwards JM, Moneta GL, Taylor LM, Jr, Porter JM. Human saphenous vein grafts explanted from the arterial circulation demonstrate altered smooth-muscle and endothelial responses. J Vasc Surg. 1993 Jul;18(1):61–8. doi: 10.1067/mva.1993.42071. discussion 8-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz LB, Purut CM, Massey MF, Pence JC, Smith PK, McCann RL. Effects of pulsatile perfusion on human saphenous vein vasoreactivity: a preliminary report. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996 Apr;4(2):143–9. doi: 10.1016/0967-2109(96)82305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinia-Feenstra M, Stooker W, de Graaf R, Kloek JJ, Pfaffendorf M, de Mol BA, van Zwieten PA. Functional properties of the saphenous vein harvested by minimally invasive techniques. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000 Apr;69(4):1116–20. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furchgott RF. Role of endothelium in responses of vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res. 1983 Nov;53(5):557–73. doi: 10.1161/01.res.53.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wingard CJ, Browne AK, Murphy RA. Dependence of force on length at constant cross-bridge phosphorylation in the swine carotid media. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;488(Pt 3):729–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021004. 11/1/1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai TR, Bates JH, Brusasco V, Camoretti-Mercado B, Chitano P, Deng LH, Dowell M, Fabry B, Ford LE, Fredberg JJ, Gerthoffer WT, Gilbert SH, Gunst SJ, Hai CM, Halayko AJ, Hirst SJ, James AL, Janssen LJ, Jones KA, King GG, Lakser OJ, Lambert RK, Lauzon AM, Lutchen KR, Maksym GN, Meiss RA, Mijailovich SM, Mitchell HW, Mitchell RW, Mitzner W, Murphy TM, Pare PD, Schellenberg RR, Seow CY, Sieck GC, Smith PG, Smolensky AV, Solway J, Stephens NL, Stewart AG, Tang DD, Wang L. On the terminology for describing the length-force relationship and its changes in airway smooth muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2004 Dec;97(6):2029–34. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00884.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herlihy JT, Murphy RA. Length-tension relationship of smooth muscle of the hog carotid artery. Circ Res. 1973 Sep;33(3):275–83. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galambos B, Csonge L, Olah A, von Versen R, Tamas L, Zsoldos P. Quantitative reduction of methyl tetrazolium by fresh vein homograft biopsies in vitro is an index of viability. Eur Surg Res. 2004 Nov-Dec;36(6):371–5. doi: 10.1159/000081647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalil RA, Crews JK, Novak J, Kassab S, Granger JP. Enhanced vascular reactivity during inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 1998 May;31(5):1065–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.5.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent KC, Liu B. Intimal hyperplasia--still here after all these years! Ann Vasc Surg. 2004 Mar;18(2):135–7. doi: 10.1007/s10016-004-0019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann MJ, Whittemore AD, Donaldson MC, Belkin M, Conte MS, Polak JF, Orav EJ, Ehsan A, Dell'Acqua G, Dzau VJ. Ex-vivo gene therapy of human vascular bypass grafts with E2F decoy: the PREVENT single-centre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 1999 Oct 30;354(9189):1493–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)09405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okon EB, Millar MJ, Crowley CM, Bashir JG, Cook RC, Hsiang YN, McManus B, van Breemen C. Effect of moderate pressure distention on the human saphenous vein vasomotor function. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004 Jan;77(1):108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.06.007. discussion 14-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer DM, Rogers TE, Jessen ME, Estrera AS, Chin AK. Histologic evidence of the safety of endoscopic saphenous vein graft preparation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000 Aug;70(2):487–91. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabricius AM, Diegeler A, Doll N, Weidenbach H, Mohr FW. Minimally invasive saphenous vein harvesting techniques: morphology and postoperative outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000 Aug;70(2):473–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01370-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campeau L, Enjalbert M, Lesperance J, Vaislic C, Grondin CM, Bourassa MG. Atherosclerosis and late closure of aortocoronary saphenous vein grafts: sequential angiographic studies at 2 weeks, 1 year, 5 to 7 years, and 10 to 12 years after surgery. Circulation. 1983 Sep;68(3 Pt 2):II1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wernig F, Mayr M, Xu Q. Mechanical stretch-induced apoptosis in smooth muscle cells is mediated by beta1-integrin signaling pathways. Hypertension. 2003 Apr;41(4):903–11. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000062882.42265.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldman J, Zhong L, Liu SQ. Degradation of alpha-actin filaments in venous smooth muscle cells in response to mechanical stretch. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003 May;284(5):H1839–47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00470.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayr M, Li C, Zou Y, Huemer U, Hu Y, Xu Q. Biomechanical stress-induced apoptosis in vein grafts involves p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. FASEB J. 2000 Feb;14(2):261–70. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornelissen J, Armstrong J, Holt CM. Mechanical stretch induces phosphorylation of p38-MAPK and apoptosis in human saphenous vein. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004 Mar;24(3):451–6. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000116690.17017.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Q, Li W, Quan Z, Sumpio BE. Modulation of vascular smooth muscle cell alignment by cyclic strain is dependent on reactive oxygen species and P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Vasc Surg. 2003 Mar;37(3):660–8. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Standley PR, Cammarata A, Nolan BP, Purgason CT, Stanley MA. Cyclic stretch induces vascular smooth muscle cell alignment via NO signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002 Nov;283(5):H1907–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01043.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadananda P, Shang F, Liu L, Mansfield KJ, Burcher E. Release of ATP from rat urinary bladder mucosa: role of acid, vanilloids and stretch. Br J Pharmacol. 2009 Dec;158(7):1655–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zampetaki A, Zhang Z, Hu Y, Xu Q. Biomechanical stress induces IL-6 expression in smooth muscle cells via Ras/Rac1-p38 MAPK-NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005 Jun;288(6):H2946–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00919.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chamberlain J, Evans D, King A, Dewberry R, Dower S, Crossman D, Francis S. Interleukin-1beta and signaling of interleukin-1 in vascular wall and circulating cells modulates the extent of neointima formation in mice. Am J Pathol. 2006 Apr;168(4):1396–403. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tock J, Van Putten V, Stenmark KR, Nemenoff RA. Induction of SM-alpha-actin expression by mechanical strain in adult vascular smooth muscle cells is mediated through activation of JNK and p38 MAP kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003 Feb 21;301(4):1116–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albinsson S, Nordstrom I, Hellstrand P. Stretch of the vascular wall induces smooth muscle differentiation by promoting actin polymerization. J Biol Chem. 2004 Aug 13;279(33):34849–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shyu KG, Chang ML, Wang BW, Kuan P, Chang H. Cyclical mechanical stretching increases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001 Nov;100(11):741–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]