Abstract

The reference standard for making a diagnosis of hypertension among hemodialysis patients is 44-hour interdialytic ambulatory BP monitoring. However, a more practical way to diagnose and manage hypertension is to perform home BP monitoring that spans the interdialytic interval. In contrast to pre- and postdialysis BP recordings, measurements of BP made outside the dialysis unit correlate with the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy and directly and strongly with all-cause mortality. Hypervolemia that is not clinically obvious is the most common treatable cause of difficult to control hypertension; volume control should be the initial therapy to treat hypertension in most hemodialysis patients. To diagnose hypervolemia, continuous blood volume monitoring is emerging as an effective and simple technique. Reducing dietary and dialysate sodium is an often overlooked strategy to improve BP control. Although definitive randomized trials that demonstrate cardiovascular benefits of BP lowering among hypertensive hemodialysis have not been performed, emerging evidence suggests that lowering BP may reduce cardiovascular events. Since predialysis and post-dialysis BP are quite variable and agree poorly with measurements obtained outside the dialysis unit, treatment should be guided by BP obtained outside the dialysis unit. While the appropriate level to which BP should be lowered remains elusive, current data suggests that interdialytic ambulatory systolic BP should be lowered to <130 mmHg and averaged home systolic BP to <140 mmHg. Antihypertensive drugs will be required by most patients receiving 4 hour thrice weekly dialysis. Beta blockers, dihydropyridine calcium blockers and agents that block the renin-angiotensin system appear to be effective in lowering BP in these patients.

Keywords: Hypertension, diagnosis, hemodialysis, home BP monitoring, ambulatory BP monitoring, treatment, pathophysiology

Introduction

In the general population, hypertension is among the most common and modifiable cardiovascular risk factors present and accounts for a large burden of cardiovascular events. Compared to the general population, hypertension is much harder to control among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) 1. The prevalence of poorly controlled hypertension among those without CKD in a large community-based survey was 52% 1. However, among patients with CKD not on dialysis, the prevalence of poorly controlled hypertension was 69% 1. Among patients with CKD not on dialysis, participating in the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP), the control rate was only 13.2% 2. Among chronic hemodialysis patients, control rate was only 30% 3. However the prevalence estimates among dialysis patients have been derived using predialysis or postdialysis blood pressure (BP) measurement which may not be optimal. This is because the diagnosis of hypertension among hemodialysis patients using pre-dialysis and post-dialysis BP recordings has many problems as discussed below.

Diagnosis

Blood pressure increases between dialysis and falls with dialysis, therefore compared to the general population, the variability in BP is more among dialysis patients. Because of both an increased variability and the gradual increase in BP between dialysis, hypertension among hemodialysis patients is best diagnosed by measuring BP intermittently every 20–30 minutes over the 44-hour interdialytic interval using a fully automated ambulatory BP monitor 4–6. It is quite likely that the prevalence estimates of hypertension derived by pre-dialysis and post-dialysis BP are misleading and variable because of different thresholds that are often used to diagnose hypertension 7. Using ambulatory BP, only one in three patients was found to have poorly controlled hypertension as defined as day-time ambulatory BP of <135/85 mmHg 8. This is in sharp contrast to 86% prevalence rates derived when simply pre-dialysis BP is taken into account 3. Ambulatory BP is also superior to pre- and post-dialysis recordings because in contrast to BP recorded in the dialysis unit, ambulatory BP better correlates with left ventricular hypertrophy 9 and all-cause mortality 10. A long-term follow up study demonstrated that in contrast to pre-dialysis or post-dialysis measurements, ambulatory BP was the best predictor of all-cause mortality 11.

However, ambulatory BP monitoring is a cumbersome technique and performing ambulatory BP measurements in all patients is difficult 12. Home BP monitoring is a more practical way to diagnose and treat hypertension in these patients 8,13. In contrast to BP recorded in the dialysis unit, self-recorded home BP better correlates with left ventricular hypertrophy and all-cause mortality 9,10. When measuring home BP, patients should be provided with validated machines, the correct cuff size and proper instruction 14. A device equipped with memory facilitates to average the readings and makes it simpler to act upon the measurements.

BP increases over the interdialytic interval, therefore timing of home BP measurements is critical 15. Although further work is warranted, we measure home BP in triplicate, twice daily (morning and late evening) for 4 days after mid-week dialysis to provide the best estimate of average BP 16. Predialysis and post-dialysis BP recordings are variable and should be avoided to guide antihypertensive therapy 17,18. However, if home BP monitoring is not possible or feasible, median intradialytic BP during a midweek dialysis may be used to make a diagnosis of hypertension 19. The threshold median intradialytic BP best associated with interdialytic hypertension is 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic 19. Median intradialytic BP can also track changes in dry-weight. However, the prediction of change in BP for any given individual is difficult 20.

Current guidelines target the pre-dialysis BP to <140/90 mmHg and post-dialysis BP to <130/80 mmHg 21. These guidelines are based on extrapolation of data from the population of patients with normal kidneys. A meta-analysis found poor agreement between pre-dialysis BP and interdialytic ambulatory BP 17. Likewise, it found poor agreement between ambulatory BP and post-dialysis BP. Furthermore, achieving BP goals prescribed by the guidelines is associated with more intradialytic hypotension 22. The management of hypertension among hemodialysis patients therefore should be guided by home BP monitoring and not pre-dialysis and post-dialysis measurements.

Although the exact threshold of diagnosis of hypertension is uncertain, systolic BP of 130 mmHg recorded by average 44-hour ambulatory systolic BP and 140 mmHg by home BP (recorded three times daily for one week) are associated with poor outcomes 10. Thus interdialytic ambulatory systolic BP of >=130 mmHg or home BP >=140 mmHg may be regarded as hypertensive.

Mechanisms

The single most important factor that initiates, sustains, or aggravates hypertension among hemodialysis patients is hypervolemia. Hypervolemia often does not manifest with clinical signs and symptoms of volume overload but is often occult 23; the sole manifestation of hypervolemia in a hemodialysis patient may be interdialytic hypertension.

Among hemodialysis patients it has long been thought that dietary or dialysate-induced accumulation of sodium is accompanied by increase in thirst that leads to a commensurate retention of water to maintain the isotonicity of body fluids. Recent data appear to show that a high-salt diet in rats leads to interstitial hypertonic sodium accumulation in skin, resulting in increased density and hyperplasia of the lymphcapillary network. The mechanisms underlying these effects on lymphatics involve activation of tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein (TonEBP) in macrophages infiltrating the interstitium of the skin. Activation of TonEBP causes vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C secretion by macrophages. Interrupting VEGF-C signaling augments interstitial hypertonic volume retention and elevates BP in response to high salt diet 24. These data provide support to the notion, that besides external sodium balance, the redistribution of sodium between the skin and circulation provides extrarenal regulation of body fluid volume and BP control.

Sympathetic activation is likely the second most important factor in sustaining hypertension among hemodialysis patients 25. In this regard, the anatomically intact but functionally absent kidney serve as a large sensory organ which activate the sympathetic nervous system to cause hypertension 26. Renalase is a novel enzyme that degrades circulating catecholamines and may be important in causing hypertension among hemodialysis patients 27. Nephrectomy lowers blood pressure but beta blockers are very effective in lowering BP among hemodialysis patients 28,29. Somewhat surprisingly, clonidine is much less effective compared to beta blockers in lowering BP 30.

Several vasoconstrictive stimuli may aggravate hypertension such as: 1) an activated renin angiotensin system. Drugs that lower the activity of the renin angiotensin system are effective in controlling hypertension 31. 2) High circulating levels of asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA) block the normal function of nitric oxide synthase and may aggravate hypertension 32. High levels of nitric oxide end products in hypotensive patients and low levels in hypertensive patients suggest the pathophysiologic importance of nitric oxide in BP control among hemodialysis patients 33. 3) Endothelin receptor activation. Recent evidence suggests that a selective endothelin type A antagonist, darusentan, can lower BP in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension 34. However, none of these patients were on hemodialysis.

The role of intracellular calcium excess due to secondary hyperparathyroidism in causing hypertension is unclear. One study found that among elderly with little or no kidney disease, serum PTH levels was strongly associated with ambulatory blood pressure, particularly the nocturnal BP 35. However, another reported that among hypertensive patients undergoing parathyroidectomy, BP was not affected 36.

Drugs are often an overlooked cause of aggravated hypertension among hemodialysis patients. Cocaine exposure can lead to tremendous elevation in BP in patients with kidney disease and should be considered when hypertension is difficult to control. Drugs such as, NSAIDs, nasal decongestants and more commonly erythropoietin 37 can aggravate hypertension. The mechanism of hypertension with erythropoietin remains unclear but the rise in BP with erythropoietin administration appears to be independent of the rise in hematocrit 38–41. For example, Vaziri et al have shown that if erythropoietin is administered to anemic rodents with chronic renal failure, but hemoglobin is kept stable by feeding these animals an iron deficient diet, hypertension still occurs 42. In blood vessels harvested from these animals treated with erythropoietin, vasodilatory response to nitric oxide donors is impaired, but response to several vasoconstrictors was normal. This impairment in vasodilatory response may be related to smooth muscle dysfunction. Vascular smooth muscle cells utilize intracellular Ca to initiate vasoconstriction 43. Since platelet cytosolic Ca concentrations correlates well with vascular smooth muscle cytosolic Ca concentrations platelet cytosolic Ca serves as a surrogate for smooth muscle Ca concentration 44. In this context, erythropoietin increases platelet cytosolic calcium in animals 42 as well as among hypertensive patients 45.

The critical importance of nitric oxide in erythropoietin-induced hypertension has been dissected in a mouse model 46. Transgenic mice overexpressing human erythropoietin were generated. Despite hematocrit levels of 80%, adult transgenic mice did not develop hypertension or thromboembolism because endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase levels, NO-mediated endothelium-dependent relaxation and circulating and vascular tissue NO levels were markedly increased. Administration of the NO synthase inhibitor N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) led to vasoconstriction of peripheral resistance vessels, hypertension, and death of transgenic mice, whereas wild-type siblings developed hypertension but did not show increased mortality. L-NAME-treated polyglobulic mice revealed acute left ventricular dilatation and vascular engorgement associated with pulmonary congestion and hemorrhage. Thus endothelial NO appears to be critical in maintaining normotension, preventing cardiovascular dysfunction, and survival in vivo when erythropoietin is used.

Concomitant conditions that aggravate hypertension include increased arterial stiffness 47 and sleep-apnea 48. In one study of unselected long-term dialysis patients, arterial stiffness was the strongest correlate of interdialytic hypertension 49.

Treatment and Outcomes

The treatment targets remain unknown. However, because systolic BP of ≥ 130 mmHg recorded by ambulatory and ≥ 140 mmHg by home BP are associated with poor outcomes, 44 hour ambulatory systolic BP should be lowered to <130 mmHg and home systolic BP to <140 mmHg. These targets may be especially difficult to achieve in patients who experience frequent symptomatic intradialytic hypotension.

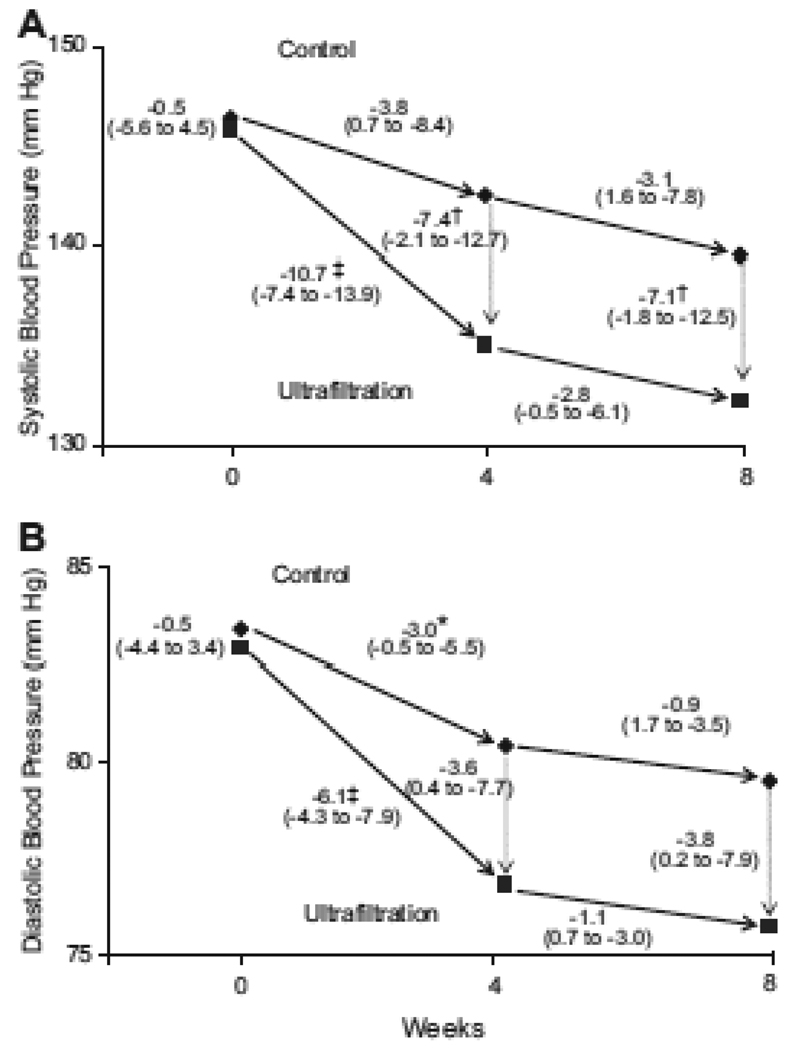

Although there are few randomized trials to guide therapy, volume control should take center stage in the management of hypertension. In the recently reported dry-weight reduction in hypertensive hemodialysis patients (DRIP) trial, long-term hypertensive hemodialysis patients were randomly assigned to ultrafiltration or control groups 13. The additional ultrafiltration group (n=100) had the dry weight probed without increasing time or duration of dialysis, whereas the control group (n=50) only had physician visits. Postdialysis weight was reduced by 0.9 kg at 4 weeks and resulted in −6.9 mm Hg (95% CI: −12.4 to −1.3 mm Hg; P=0.016) change in systolic BP (Figure) and −3.1 mm Hg (95% CI: −6.2 to −0.02 mm Hg; P=0.048) change in diastolic BP. At 8 weeks, dry weight was reduced 1 kg, systolic BP changed −6.6 mm Hg (95% CI: −12.2 to −1.0 mm Hg; P=0.021), and diastolic BP changed −3.3 mm Hg (95% CI: −6.4 to −0.2 mm Hg; P=0.037) from baseline. The Mantel-Hanzel combined odds ratio for systolic BP reduction of > or =10 mm Hg was 2.24 (95% CI: 1.32 to 3.81; P=0.003). There was no deterioration seen in any domain of the kidney disease quality of life health survey despite an increase in intradialytic signs and symptoms of hypotension. Nonetheless several possible risks of challenging dry weight include the following: intradialytic hypotension (and possibly myocardial stunning), loss of residual renal function, increased risk of access clotting, and possibly increased post dialysis fatigue and postdialysis symptoms.

Figure 1.

The effect of dry-weight reduction on interdialytic ambulatory systolic (Panel A) and diastolic blood pressure (Panel B) in hypertensive hemodialysis patients. The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures are shown for the baseline control and ultrafiltration groups. The mean changes in blood pressure are shown for weeks 4 and 8 following randomization (solid arrows), and the mean differences in blood pressures (dotted arrows) between the two groups at each 4 week interval. The numbers next to the dotted lines connecting the data points are the mean changes in blood pressure between groups at 4 and 8 weeks following randomization. The 95% confidence intervals are given in parentheses. Asterisks (p<0.05), daggers (p<0.01) and double daggers (p<0.001) indicate significant differences between groups or within groups. The ultrafiltration-attributable change in systolic BP was −6.9 mm Hg (95% CI −12.4, −1.3 mm Hg, p=0.016) at 4 weeks and −6.6 mm Hg (95% CI −12.2, −1.0 mm Hg, p=0.021) at 8 weeks. The ultrafiltration-attributable change in diastolic BP was −3.1 mm Hg (95% CI −6.2, −0.02 mm Hg, p=0.048) at 4 weeks and −3.3 mm Hg (95% CI −6.4, −0.2 mm Hg, p=0.037) at 8 weeks.

Although the above results were achieved by assessing the dry-weight at the bedside, recent findings indicate that relative blood volume can be assessed by intradialytic relative plasma volume monitoring 50. Determination of the extent of both intradialytic decreases in blood volume by intradialytic relative plasma volume monitoring, combined with clinical assessment of intradialytic hypovolemia and postdialytic fatigue, can help assess patient dry weight and optimize volume status while reducing dialysis associated morbidity 51. Studies among hemodialysis patients in both adults and children suggest that managing intradialytic relative plasma volume may reduce the number of hospital admissions due to fluid overload 51,52, improve BP control and decrease hypotension associated dialysis symptoms 53. Accordingly, monthly monitoring of relative blood volume and home BP may offer an attractive way to assess the adequacy of volume control among hemodialysis patients. This technology is commercially available (such as Critline, Hema Metrics, Kayesville, UT) and is relatively inexpensive to use.

Limiting sodium intake is important but like most life-style changes are difficult to implement. A meta-analysis of trials of sodium restriction in normotensive and hypertensive individuals concluded that 50 mEq/d reduction in dietary sodium, (that can simply be achieved by taking away table salt), would lead to fall in systolic blood pressure of 5 mm Hg on average and by 7 mm Hg in those who are more hypertensive 54. Furthermore, at least 5 weeks of sodium restriction would be required to see such an effect. However, a much easier way to reduce sodium exposure is to lower dialysate sodium 55. In some patients this may not be tolerated. Reducing the dialysate temperature to 35°C may help sustain intra-dialytic BP in such patients.

Patients often miss dialysis or reduce the time on dialysis. This may be a significant but often overlooked factor in aggravating hypertension and one that is not always captured by the measurement of Kt/V. Compliance with dialysis therapy should be carefully assessed in those individuals with difficult to control hypertension.

Antihypertensive therapy has been associated with reduction in cardiovascular events but not mortality among hemodialysis patients 56,57. This benefit is seen mostly among patients who have hypertension 57. Accordingly, the benefits likely accrue because of BP lowering among these patients. Antihypertensive therapy will be required by most patients on hemodialysis dialyzed three times weekly for about 4 hours.

Long-duration dialysis has been reported to lower BP 58. However, controlled trials are notable by their absence 59. In an encouraging report, long-duration dialysis was found to regress left ventricular hypertrophy 60. This may have occurred due to better volume control or removal of circulating asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA) or other uremic toxins that elevate BP.

Transplantation has been associated with better BP control but hypertension often persists and may even be aggravated 61. This is so because of the immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors that often raise BP.

In conclusion, management of hypertension among hemodialysis patients may be improved should home BP monitoring that spans the interdialytic interval be performed on a regular basis. In contrast to pre- and post-dialysis BP recordings, measurements of BP made outside the dialysis unit correlate with the presence of target organ damage (left ventricular hypertrophy) and directly and strongly with all-cause mortality. Hypervolemia that is not clinically obvious is the most common treatable cause of difficult to control hypertension; volume control should be the initial therapy to treat hypertension in most hemodialysis patients. To diagnose hypervolemia, continuous blood volume monitoring is emerging as an effective and simple technique. Reducing dietary and dialysate sodium is an often overlooked strategy to improve BP control. Although definitive randomized trials that demonstrate cardiovascular benefits of BP lowering among hypertensive hemodialysis have not been performed, emerging evidence suggests that lowering BP may reduce cardiovascular events. While the appropriate level to which BP should be lowered remains elusive, current data suggests that interdialytic ambulatory systolic BP should be lowered to <130 mmHg and averaged home systolic BP to <140 mmHg. Most patients receiving 4 hour thrice weekly dialysis will require antihypertensive drugs. Beta blockers, dihydropyridine calcium blockers and agents that block the renin-angiotensin system all appear to be effective in lowering BP in these patients.

Acknowledgement

Supported by a research award from NIH (NIDDK 2 RO1- DK062030-06)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Plantinga LC, Miller ER, III, Stevens LA, et al. Blood pressure control among persons without and with chronic kidney disease: US trends and risk factors 1999–2006. Hypertension. 2009;54:47–56. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.129841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarafidis PA, Li S, Chen SC, et al. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2008;121:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal R, Nissenson AR, Batlle D, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension in chronic hemodialysis patients in the United States. Am J Med. 2003;115:291–297. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agarwal R. Assessment of blood pressure in hemodialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2002;15:299–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2002.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley K, Light RP, Agarwal R. Trended cosinor change model for analyzing hemodynamic rhythm patterns in hemodialysis patients. Hypertension. 2007;50:143–150. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.091579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal R. Volume-Associated Ambulatory Blood Pressure Patterns in Hemodialysis Patients. Hypertension. 2009;54:241–247. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.136366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal R. Hypertension diagnosis and prognosis in chronic kidney disease with out-of-office blood pressure monitoring. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:309–313. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000222700.14960.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agarwal R, Andersen MJ, Bishu K, et al. Home blood pressure monitoring improves the diagnosis of hypertension in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69:900–906. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal R, Brim NJ, Mahenthiran J, et al. Out-of-hemodialysis-unit blood pressure is a superior determinant of left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2006;47:62–68. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000196279.29758.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alborzi P, Patel N, Agarwal R. Home blood pressures are of greater prognostic value than hemodialysis unit recordings. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:1228–1234. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02250507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal R. Blood pressure and mortality among hemodialysis patients. Hypertension. 2010;55:762–768. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal R. Managing hypertension using home blood pressure monitoring among haemodialysis patients--a call to action. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal R, Satyan S, Alborzi P, et al. Home blood pressure measurements for managing hypertension in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:126–134. doi: 10.1159/000206698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society Of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52:10–29. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.189010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal R, Light RP. Chronobiology of arterial hypertension in hemodialysis patients: implications for home blood pressure monitoring. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:693–701. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal R, Andersen MJ, Light RP. Location Not Quantity of Blood Pressure Measurements Predicts Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. Am J Nephrol. 2007;28:210–217. doi: 10.1159/000110090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal R, Peixoto AJ, Santos SF, et al. Pre and post dialysis blood pressures are imprecise estimates of interdialytic ambulatory blood pressure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:389–398. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01891105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohrscheib MR, Myers OB, Servilla KS, et al. Age-related blood pressure patterns and blood pressure variability among hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1407–1414. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00110108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal R, Metiku T, Tegegne GG, et al. Diagnosing hypertension by intradialytic blood pressure recordings. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1364–1372. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01510308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal R, Light RP. Median Intradialytic Blood Pressure Can Track Changes Evoked by Probing Dry-Weight. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 doi: 10.2215/CJN.08341109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:S1–S153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davenport A, Cox C, Thuraisingham R. Achieving blood pressure targets during dialysis improves control but increases intradialytic hypotension. Kidney Int. 2007;73:759–764. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal R, Andersen MJ, Pratt JH. On the importance of pedal edema in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:153–158. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03650807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Machnik A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, et al. Macrophages regulate salt-dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor-C-dependent buffering mechanism. Nat Med. 2009;15:545–552. doi: 10.1038/nm.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Converse RLJr, Jacobsen TN, Toto RD, et al. Sympathetic overactivity in patients with chronic renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1912–1918. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212313272704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen J, Victor RG. Direct measurements of sympathetic activity: new insights into disordered blood pressure regulation in chronic renal failure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1994;3:636–643. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199411000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu J, Li G, Wang P, et al. Renalase is a novel, soluble monoamine oxidase that regulates cardiac function and blood pressure. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1275–1280. doi: 10.1172/JCI24066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agarwal R. Supervised atenolol therapy in the management of hemodialysis hypertension. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1528–1535. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maggiore Q, Biagini M, Zoccali C, et al. Long-term propranolol treatment of resistant arterial hypertension in haemodialysed patients. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1975 Suppl 2:73s–75s. doi: 10.1042/cs048073s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosansky SJ, Johnson KL, McConnel J. Use of transdermal clonidine in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 1993;39:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agarwal R, Lewis RR, Davis JL, et al. Lisinopril therapy for hemodialysis hypertension – Hemodynamic and endocrine responses. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:1245–1250. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.29221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Maas R, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac remodeling and asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:339–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erkan E, Devarajan P, Kaskel F. Role of nitric oxide, endothelin-1, and inflammatory cytokines in blood pressure regulation in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:76–81. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber MA, Black H, Bakris G, et al. A selective endothelin-receptor antagonist to reduce blood pressure in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morfis L, Smerdely P, Howes LG. Relationship between serum parathyroid hormone levels in the elderly and 24 h ambulatory blood pressures. J Hypertens. 1997;15:1271–1276. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715110-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ifudu O, Matthew JJ, Macey LJ, et al. Parathyroidectomy does not correct hypertension in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol. 1998;18:28–34. doi: 10.1159/000013301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krapf R, Hulter HN. Arterial hypertension induced by erythropoietin and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:470–480. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05040908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muntzel M, Hannedouche T, Lacour B, et al. Erythropoietin increases blood pressure in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Nephron. 1993;65:601–604. doi: 10.1159/000187571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmieder RE, Langenfeld MR, Hilgers KF. Endogenous erythropoietin correlates with blood pressure in essential hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:376–382. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones MA, Kingswood JC, Dallyn PE, et al. Changes in diurnal blood pressure variation and red cell and plasma volumes in patients with renal failure who develop erythropoietin-induced hypertension. Clin Nephrol. 1995;44:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaupke CJ, Kim S, Vaziri ND. Effect of erythrocyte mass on arterial blood pressure in dialysis patients receiving maintenance erythropoietin therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;4:1874–1878. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V4111874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaziri ND, Zhou XJ, Naqvi F, et al. Role of nitric oxide resistance in erythropoietin-induced hypertension in rats with chronic renal failure. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E113–E122. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.1.E113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inscho EW, Cook AK, Mui V, et al. Calcium mobilization contributes to pressure-mediated afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction. Hypertension. 1998;31:421–428. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erne P, Bolli P, Burgisser E, et al. Correlation of platelet calcium with blood pressure. Effect of antihypertensive therapy. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1084–1088. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404263101705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tepel M, Wischniowski H, Zidek W. Erythropoietin induced transmembrane calcium influx in essential hypertension. Life Sci. 1992;51:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90010-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruschitzka FT, Wenger RH, Stallmach T, et al. Nitric oxide prevents cardiovascular disease and determines survival in polyglobulic mice overexpressing erythropoietin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11609–11613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pannier B, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, et al. Stiffness of capacitive and conduit arteries: prognostic significance for end-stage renal disease patients. Hypertension. 2005;45:592–596. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000159190.71253.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iliescu EA, Yeates KE, Holland DC. Quality of sleep in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:95–99. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agarwal R, Light RP. Arterial stiffness and interdialytic weight gain influence ambulatory blood pressure patterns in hemodialysis patients. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;294:F303–F308. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00575.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agarwal R, Kelley K, Light RP. Diagnostic utility of blood volume monitoring in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:242–254. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodriguez HJ, Domenici R, Diroll A, et al. Assessment of dry weight by monitoring changes in blood volume during hemodialysis using Crit-Line. Kidney Int. 2005;68:854–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldstein SL, Smith CM, Currier H. Noninvasive interventions to decrease hospitalization and associated costs for pediatric patients receiving hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2127–2131. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000076077.05508.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel HP, Goldstein SL, Mahan JD, et al. A standard, noninvasive monitoring of hematocrit algorithm improves blood pressure control in pediatric hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:252–257. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02410706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Law MR, Frost CD, Wald NJ. By how much does dietary salt reduction lower blood pressure? III--Analysis of data from trials of salt reduction. BMJ. 1991;302:819–824. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6780.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Paula FM, Peixoto AJ, Pinto LV, et al. Clinical consequences of an individualized dialysate sodium prescription in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1232–1238. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heerspink HJ, Ninomiya T, Zoungas S, et al. Effect of lowering blood pressure on cardiovascular events and mortality in patients on dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60212-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agarwal R, Sinha AD. Cardiovascular protection with antihypertensive drugs in dialysis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2009;53:860–866. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.128116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fagugli RM, Pasini P, Quintaliani G, et al. Association between extracellular water, left ventricular mass and hypertension in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:2332–2338. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh M, Culleton B, Tonelli M, et al. A systematic review of the effect of nocturnal hemodialysis on blood pressure, left ventricular hypertrophy, anemia, mineral metabolism, and health-related quality of life. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1500–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Culleton BF, Walsh M, Klarenbach SW, et al. Effect of frequent nocturnal hemodialysis vs conventional hemodialysis on left ventricular mass and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1291–1299. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.11.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Agarwal R, Peixoto AJ, Santos SF, et al. Out-of-office blood pressure monitoring in chronic kidney disease. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14:2–11. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283262f58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]