Abstract

The glycoprotein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) contains nine potential N-linked glycosylation sites. We investigated the function of these N-glycosylations by using alanine-scanning mutagenesis. All the available sites were occupied on GP1 and two of three on GP2. N-linked glycan mutations at positions 87 and 97 on GP1 resulted in reduction of expression and absence of cleavage and were necessary for downstream functions, as confirmed by the loss of GP-mediated fusion activity with T87A, S97A mutants. In contrast, T234A and E379N/A381T mutants impaired GP-mediated cell fusion without altered expression or processing. Infectivity via virus-like particles required glycans and a cleaved glycoprotein. Glycosylation at the first site within GP2, not normally utilized by LCMV, exhibited increased VLP-infectivity. We also confirmed the role of the N-linked glycan at position 173 in the masking of the neutralizing epitope GP-1D. Taken together, our results indicated a strong relationship between fusion and infectivity.

Keywords: Arenavirus, Envelope glycoprotein, Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, Glycosylation, Epitope, Membrane fusion, Mutagenesis

Introduction

The Arenaviridae are enveloped RNA viruses generally associated with rodent-transmitted disease in humans, where they can induce both neurological and systemic disease. The diseases induced by each of these viruses range from mild infections to severe life-threatening acute febrile illnesses in which shock is a frequent feature. Headache, lethargy, fever, myalgia, abdominal pain, and conjunctivitis are early common signs in all of these infections. Encephalopathic signs with tremor, seizures, and altered consciousness may occur in the South American hemorrhagic fevers and severe Lassa fever. The spectrum of disease in humans includes aseptic to acute meningitis, self-limited neurologic syndrome, pneumonia, heart damage, kidney damage, and hemorrhagic fevers (McCormick and Fisher-Hoch, 2002; Peters and Zaki, 2002). The high degree of genetic variation among geographic and temporal isolates of the same arenavirus species supports the concept of continued emergence of new pathogens (Sevilla and de la Torre, 2006). This was sustained by a recent outbreak of five cases of undiagnosed hemorrhagic fever, four of them fatal, in South Africa in 2008. A novel arenavirus was identified and was classified as a new species, designated Lujo virus, in the genus Arenavirus (Briese et al., 2009; Paweska et al., 2009).

The prototypic arenavirus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is found worldwide. The house mouse, Mus musculus, is the natural reservoir, but LCMV can also infect other wild, pet, and laboratory rodents, and notably the index case in a recent cluster of transplantation-associated deaths was traced to a pet hamster (Amman et al., 2007; Deibel et al., 1975; Fischer et al., 2006). Humans can be infected through exposure to infected rodent excreta. Person-to-person transmission is rare, but has occurred through maternal-fetal transmission and solid organ transplantation (Barton, 2006). LCMV infection in humans can be asymptomatic or cause a spectrum of illness ranging from isolated fever to meningitis and encephalitis. Overall, the case fatality is <1%. Fetal infections can result in congenital abnormalities or death (Barton and Mets, 2001).

Virions of LCMV are composed of a nucleocapsid surrounded by a lipid bilayer, presenting spikes of glycoproteins (GP) (Neuman et al., 2005). The initial step in LCMV infection involves interaction of GP with the cellular receptor of target cells (Cao et al., 1998). After internalization of the virions within vesicles, LCMV GP mediates fusion of the viral and cellular membranes, resulting in delivery of the nucleocapsids into the cytoplasm (Borrow and Oldstone, 1994; Di Simone and Buchmeier, 1995; Di Simone, Zandonatti, and Buchmeier, 1994; Klewitz, Klenk, and ter Meulen, 2007; York et al., 2008).

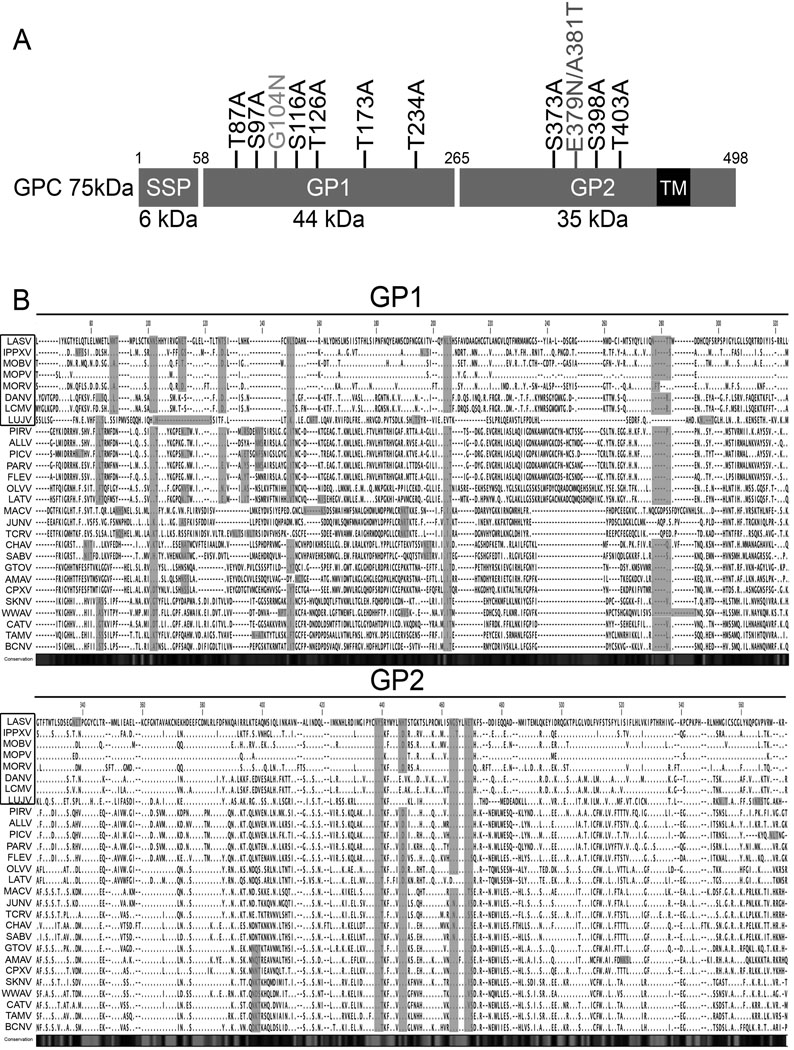

The 498-amino-acid glycoprotein complex (GPC) of LCMV consists of three domains (Fig. 1A). The stable signal peptide (SSP), GPC residues 1 to 58, is co-translationally cleaved by signal peptidase. Full length GPC is cleaved into GP1 (residues 59 to 265) and GP2 (residues 266 to 498) by the cellular protease SK-1/S1P (Beyer et al., 2003) and forms a spike complex (Wright et al., 1990). GP1 is heavily glycosylated with 6 predicted N-glycosylation sites for LCMV-Armstrong clone 5 (Arm-5) and 5 predicted N-glycosylation sites for the clone 4 (Arm-4) (Wright, Salvato, and Buchmeier, 1989). GP1 contains the receptor binding site and antibody neutralization sites, and is non-covalently associated with GP2 (Burns and Buchmeier, 1991). GP2 contains 3 predicted N-glycosylation sites and a transmembrane region that anchors the GP complex in the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane and virus envelope (Agnihothram et al., 2009; Burns and Buchmeier, 1991).

Fig. 1.

LCMV GPC. (A) LCMV glycoprotein overview. The signal peptide SSP (aa 1–58), the precursor glycoprotein GPC (aa 59–498), the subunits GP1 (aa 59–265) and GP2 (aa266–498) containing the transmembrane anchor (aa 439–456, black) are shown. Nine N-glycosylation site substitution mutants were obtained (T87A, S97A, S116A, T126A, T173A, T234A, S373A, S398A and T403A). Creation of N-glycosylation sites from Lassa virus (G104N and E379N/A381T) are represented in grey. (B) Alignment of arenavirus GP sequences. Sequence alignment of arenavirus GP1 and GP2 were done using CLC Sequence Viewer software. Colored amino acid represented the predicted N-glycosylation sites. The 8 viruses in the square represent Old World arenaviruses, while the lower part represents New World arenaviruses. Arenavirus abbreviations and accession numbers are as follows: Lassa virus (LASV), X52400; Ippy virus (IPPYV), DQ328877; Mobala virus (MOBV), AY342390; Mopeia virus (MOPV), DQ328874; Morogoro virus (MORV), EU914103; Dandenong virus (DANV), EU136038; Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), AY847350; Lujo virus (LUJV), FJ952384; Pirital virus (PIRV), AF277659; Allpahuayo virus (ALLV), AY012687; Pichinde virus (PICV), NC_006447, Parana virus (PARV), AF512829; Flexal virus (FLEV), AF512831; Oliveros virus (OLVV), U34248; Latino virus (LATV), AF512830; Machupo virus (MACV), NC_005078; Junin virus (JUNV), D10072; Tacaribe virus (TCRV), NC_004293; Chapare virus (CHAV), EU260463; Sabia virus (SABV), NC_006317; Guanarito virus (GTOV), NC_005077; Amapari virus (AMAV), AF512834; Cupixi virus (CPXV), AF512832; Skinner Tank virus (SKTV), EU123328; Whitewater Arroyo virus (WWAV), AF228063; Catarina virus (CATV), DQ865245; Tamiami virus (TAMV), AF512828; Bear Canyon virus (BCNV), AF512833.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the glycoproteins encoded by members of the Arenaviridae genus revealed that 4 N-glycosylation sites on GP2 are conserved in all members except the Old World LCMV and Dandenong lacking the second N-glycosylation site and the New World Latino lacking the third. On the contrary, there is high diversity in both the number and position of N-glycosylation sites on GP1. However, a similar pattern appears for the Old World arenaviruses, where LCMV and Dandenong lack the third N-glycosylation site compared to the other Old World arenaviruses (Fig 1B). In order to test the effect of glycan removal on a representative member of the arenavirus genus, we decided to use LCMV but to reintroduce the conserved glycosylation site on GP2 present in all the other arenaviruses as well as the conserved glycosylation site in GP1 for the old world arenaviruses.

N-linked glycosylations are important for both protein folding and function (Helenius and Aebi, 2001; Wyss and Wagner, 1996). Moreover, K. E. Wright et al demonstrated that N-linked glycosylations play a role in the formation of neutralizing epitopes for LCMV. Epitope GP-1D is a conformational epitope and is dependent on the presence of N-linked glycosylation (Wright, Salvato, and Buchmeier, 1989). It is also the case for other viruses like influenza C (Sugawara et al., 1988) and human immunodeficiency virus (Quinones-Kochs, Buonocore, and Rose, 2002).

Dramatic phenotypic differences among closely-related LCMV isolates indicate that few amino acid replacements in LCMV proteins could suffice to produce important alterations in viral biological properties (Sevilla and de la Torre, 2006). In the present study, we determined the use of various N-glycosylation sites in GPC individually and assessed their roles in protein folding, intracellular trafficking and fusion of the LCMV glycoprotein with the cell membrane. Furthermore, we generated virus-like particle (VLP) to evaluate the role of N-glycans in virus infectivity. Our results indicate that these N-glycosylation sites selectively affected a variety of downstream GP functions, including expression, cleavage, pH-dependent fusion and formation of infectious particles. Finally, we demonstrate that antibody recognition of the epitope GP-1D is blocked by the presence of an N-glycosylation site at position 173 and the epitope is restored by mutation of this N-glycosylation site.

RESULTS

Utilization of potential N-linked glycosylation sites on the LCMV glycoprotein

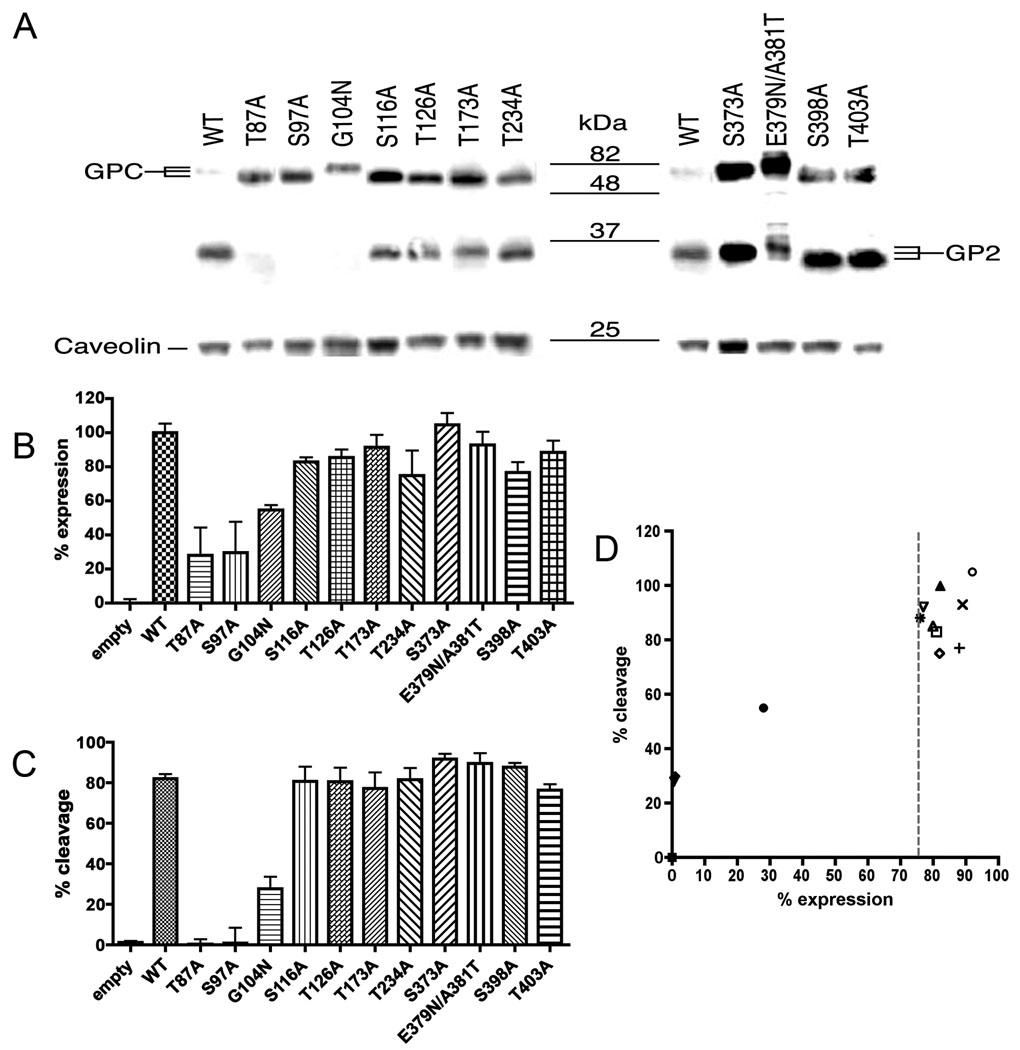

Nine potential sites for the attachment of N-linked oligosaccharides are predicted on LCMV Arm-5 glycoprotein. Two more N-glycosylation sites were added according to sequence alignment with the Old Word arenavirus Lassa strain GA391 (Nigeria), (Fig. 1A,B). These sites are characterized by Asn-X-Ser/Thr motifs. To determine the use of each site for the attachment of oligosaccharide, we mutated the 9 N-glycosylation sites by replacing the serine (S) or threonine (T) residue in the N-glycosylation motif with alanine (A). Moreover, we inserted two N-glycosylation sites present in Lassa virus within the LCMV glycoprotein (G104N and E379N/A381T). These mutants were expressed in both HEK 293T and DBT cells and cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot. Membranes were probed with monoclonal antibody 83.6, which recognizes residues 370–378 of GP2 (Weber and Buchmeier, 1988). This allowed us to detect both unprocessed GPC and cleaved GP2 at 75kDa and 35kDa respectively (Fig. 2A). LCMV N-glycosylation site mutants on LCMV GPC resulted in an increased electrophoretic mobility corresponding to a decrease of approximately 3kDa compared to wild type (wt) glycoprotein, indicating that the mutated glycoproteins lacked an oligosaccharide. This pattern was observed with all N-glycosylation site mutations on GP1. However, only the predicted N-glycosylation sites at position 398 and 403 in GP2 seemed to be used. Indeed, the first predicted N-glycosylation site of GP2 at position 373 did not exhibit an increased electrophoretic mobility. On the contrary, inserted N-glycosylation sites from Lassa virus in LCMV exhibited a gain of molecular mass (Fig. 2A). In conclusion, these data suggest that 8/9 native N-glycosylation sites were used. At the same time, the data indicated the LCMV glycoprotein was able to use non-native N-glycosylation sites inserted in GP1 and GP2.

Fig. 2.

Expression and processing of N-glycosylation mutants. (A) Western blot analysis. At 48h post-transfection, HEK 293T cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with a GP2-specific antibody, 83.6. Shifts in expected size of GPC and GP2, represented by lines next to each panel, indicate use of the mutated N-glycosylation site. (B) Total expression of N-glycosylation site mutants measured by flow cytometry. The expression for each mutated N-glycosylation sites is expressed as a percentage of wt expression. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means. (C) Percentage of cleaved GPC into GP2. (D) Correlation between percent expression and percent cleavage. Percent expression versus percent cleavage was plotted for all N-glycosylation sites mutants. Transversal dot line represents the cut-off and shows no cleavage when the % expression is < at 75%. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

N-glycosylation site mutations T87A, S97A and G104N impair GPC expression and processing

To determine the role of the N-linked glycans in GPC expression and processing, we transfected HEK 293T cells with mutated N-glycosylation site constructs and quantified the total expression of GPC/GP2 by flow cytometry (Fig. 2B). Cleavage into GP1/GP2 was analyzed with corresponding cell lysates by Western blot. The presence of the GP2 epitope in both the unprocessed GPC and the cleaved GP2 allowed us to compare efficiency of GPC cleavage into GP1 and GP2 (Fig. 2C). The results obtained from the quantification are summarized in Table 1. Most mutations did not impair GPC expression and cleavage with the exception of the T87A, S97A and less drastically G104N. These three mutants were impaired in expression of GPC and resulted in nearly undetectable levels of cleaved GP2 (Fig. 2A and B). These results highlight the functional importance at positions 87, 97 and 104 located in GP1 for expression and processing. Mutants at position 116, 126 173, 234 and 403 did not affect the cleavage compare to the wt. On the contrary, mutation S373A, E379N/A381T and S398A in GP2 improved the cleavage of the LCMV glycoprotein. To assess the correlation between cleavage and GP expression, the percentage of expression was measured by flow cytometry and the percentage of cleavage were plotted for all mutants (Fig. 2D). We observed a correlation between GPC expression and cleavage, with cleavage being impaired when the expression fell below 75% compared to the wt.

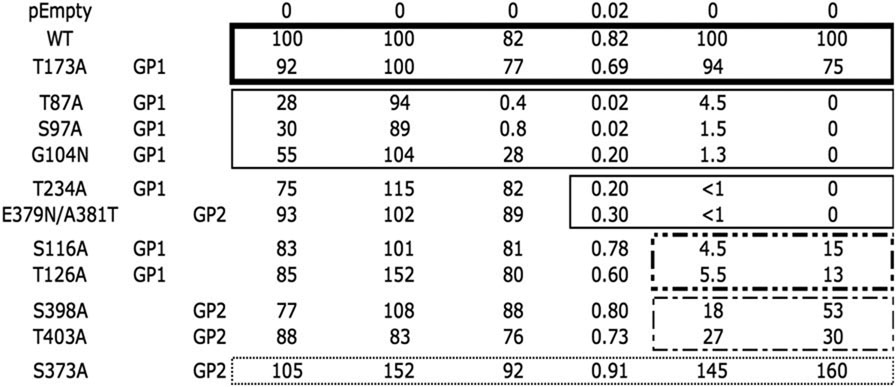

Table 1.

Biochemical properties affected by N-glycosylation site mutants organized by patterns

| Mutation | GP subunit | % GPC/GP2 expressiona |

% Surface expressionb |

% GP1/GP2 cleavagec |

Fid | % VLP infectivitye |

% pseudotype infectivity f |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

Each box represents a different pattern of altered phenotypes.

Relative to wt GPC/GP2 expression. Percent of permeabilized transfected cells labeled for GP2 and measured by flow cytometry in two replicates. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software. Mean values were analysed using GraphPad software. Standard deviations for the assay fell between 0.9 and 9.2% of the mean.

Relative to wt GPC expression. Percent of non-permeabilized transfected cells labeled for GP2 measured by flow cytometry in two replicates. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software. Mean values were analysed using GraphPad software. Standard deviations for the assay fell between 6 and 23% of the mean.

Relative intensity of GP2, expressed as percentage of the cleaved product GP2 vs total products GPC and GP2 observed in wt control transfected cells. Caveolin-1 was used as loading control. Mean values were obtained by densitometry analysis of band intensities in six replicates from Western blots probed with a GP2 specific antibody, using Quantity One software. Standard deviations ranged from 2 to 9% of the means.

Fusion index (FI), calculated using the equation FI= 1 – (number of cells / number of nuclei), based on the examination of four microscopic fields per mutant. Standard deviations ranged from 5 to 23% of the means.

Percentage of infectivity in a VLP system assay relative to wt control, as measured by CAT expression. Standard deviations ranged from 0.2 to 5% of the means.

Percentage of infectivity in a retroviral pseudotype assay relative to wt control. Standard deviations ranged from 2 to 15% of the means

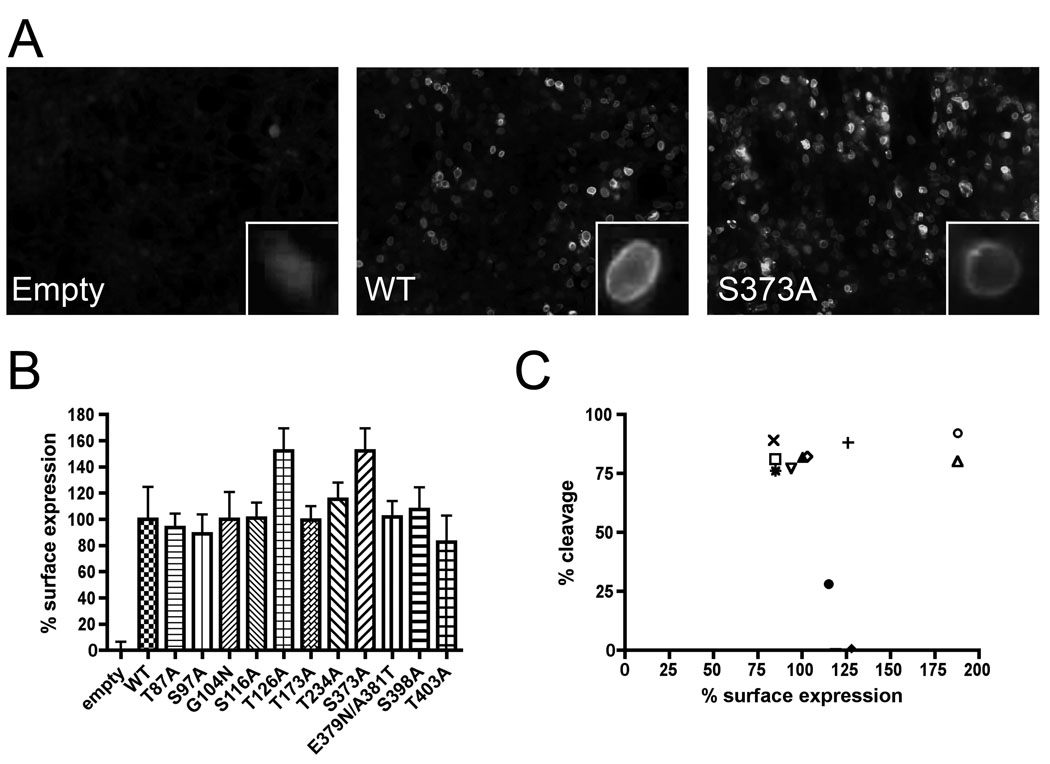

N-glycosylation site mutations did not affect cell surface localization

We examined the effects of N-glycosylation site mutations on transport of the GP complex to the cell surface, where viral assembly and budding occur. Cells were transfected with the different GP mutants and cell surface expression was assessed by immunofluorescence and by flow cytometry on non-permeabilized cells with anti-GP2 antibody. Expression levels, quantified by flow cytometry, were normalized with respect to wt. Representative results of immunofluorescence are shown in Fig. 3A, whereas a summary of the quantification is shown in Fig. 3B and Table. 1. All mutations exhibited similar or increased surface expression. It was particularly true for the mutation S373A and the N-glycosylation site mutation T126A where we observed an increase of 1.5-fold. No correlation between the surface expression and the cleavage was observed (Fig. 3C). Since cognate GPC cleavage was not required for cell surface localization as confirmed with the defective mutants T87A and S97A, N-glycosylations appeared to not be involved in GPC transport to the cell surface.

Fig. 3.

Surface glycoprotein expression. (A) Cell surface labeling in HEK 293T cells was determined by immunofluorescence using an anti-GP2 specific monoclonal antibody directly coupled to Alexa Fluor 488. Non-permeabilized cells were fixed using 1% paraformaldehyde. Images were analyzed by Image J software. (B) Surface expression of N-glycosylation site mutants. The expression for each mutated N-glycosylation site is expressed as a percentage of wt expression. (C) Correlation between percent cleavage and percent surface expression. Percent cleavage versus percent surface expression is plotted for all N-glycosylation sites mutants. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

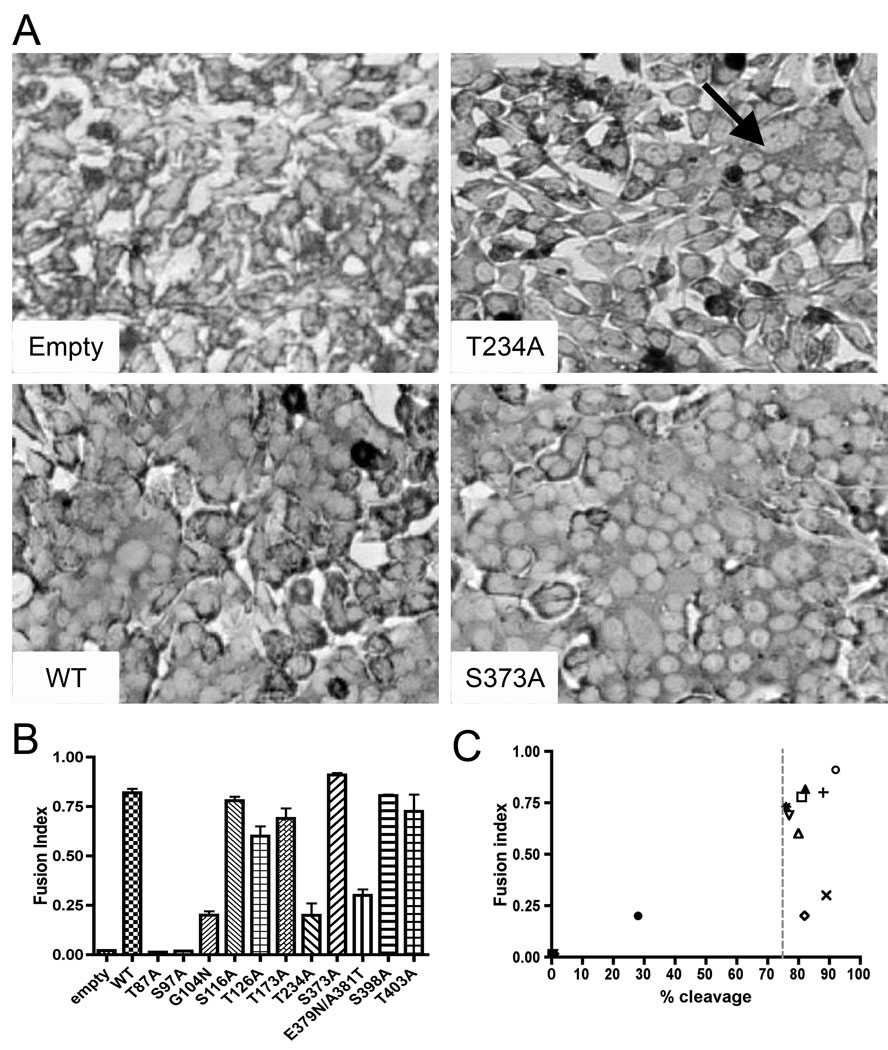

N-glycosylation site mutations T234A and E379N/A381T impair GP-mediated cell fusion

In order to investigate the possibility that N-glycosylation site mutations affected viral fusion, we tested each mutant in a cell fusion assay. N-glycosylation site mutants were transfected into DBT cells and the ability to promote syncytium formation was assessed. A representative example of the fusion assay is shown in Fig. 4A, with a summary of the results in Fig. 4B and Table 1. No GP-mediated fusion was observed for T87A and S97A mutants and N-glycosylation site mutants G104N, E379N/A381T and T234A exhibited a ≥ 50% decrease in GP-mediated fusion compare to wt. All other mutants exhibited GP-mediated fusion efficiency similar to the wt. The results of T87A, S97A and G104N mutants suggest that GP-mediated fusion at pH 5 required prior GPC cleavage. However, deletion of glycan at position 234 or addition of glycan at position 379/381, in GP2, impaired the GP-mediated cell fusion capacity. To test whether the effect of N-glycosylation site mutations on fusion events correlated with cleavage processing, fusion index versus percentage of cleavage was plotted for all N-glycosylation sites mutants (Fig. 4C). We observed fusion indices less than 0.2 when the cleavage fell below 75%, yet cleavage alone did not guarantee GP-mediated fusion.

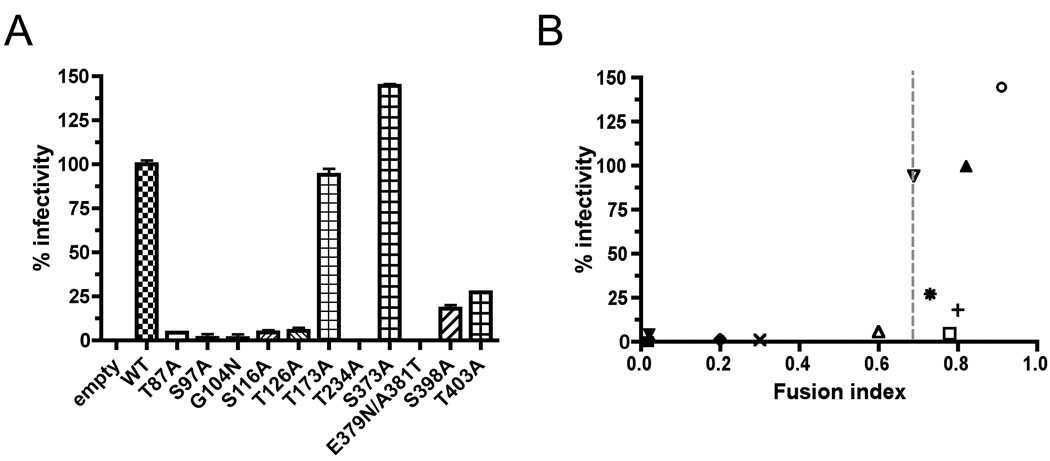

Fig. 4.

Cell fusion assay. (A) Representative DBT cell fusion assay with N-glycosylation site mutants. Transfected DBT cells were exposed to pH 5 at 48h post-transfection for 1h, then returned to neutral pH for an additional 1h, fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with Giemsa. Syncytia are marked with an arrow (B) Fusion index (FI) with N-glycosylation sites mutants. Cells were scored by using the FI for four representative fields, calculated as follows: FI = 1 – (number of cells / number of nuclei). Error bars indicate standard errors of the means. (D) Correlation between fusion index and percent cleavage. Fusion index versus percent cleavage is plotted for all N-glycosylation sites mutants. The cut off, represented by a dot line, shows no fusion when cleavage is < 75%.

N-glycosylation site mutations S116A, T126A, T173A, S398A and T403A impaired infectivity while the infectivity of mutant S373A was improved

All of the N-glycosylation sites mutants were tested for VLP infectivity, using previously described procedures (Lee et al., 2002; Saunders et al., 2007). VLP infectivity was assessed by quantifying levels of reporter gene expression in BHK cells infected with LCMV and VLP to provide the viral trans-acting factors required for RNA replication and expression of the minigenome (MG) RNA associated with infectious VLP. Results for all mutants are represented in Fig. 5A and summarized Table 1. No VLP were detectable in supernatant of transfected cells for N-glycosylation mutants T87A, S97A and G104N (data not shown). As a result, no VLP infection was detected. Despite near-wt levels of GPC expression, cell surface localization, processing, cell fusion and detection of VLP’s in supernatant of transfected cells, mutants T234A and E379N/A381T produced noninfectious VLP’s, and mutants S116A and T126A maintained only 5% infectivity. The S398A and T403A mutants formed VLP’s with 18% and 27% of infectivity, respectively. These results suggest infectious VLP’s required not only processed GPC, but also N-glycosylation sites. In contrast, mutant S373A that corresponds to the first N-glycosylation site in GP2, produced infectious VLP’s with 145% infectivity compared to the wt glycoprotein. Infectivity was also assessed by retrovirus pseudotyping (Table 1). Results were similar to the results of the VLP infectivity assay. To address the possibility that N-glycosylation site mutations affected VLP infectivity at viral fusion events, percent VLP infectivity versus fusion index (FI) was plotted for all N-glycosylation mutants (Fig. 5B). We observed no infectivity when the FI fell below 0.6. However, GP-mediated fusion alone did not guarantee particle infectivity.

Fig. 5.

N-glycosylation site mutant VLP infectivity. (A) The VLP infectivity for each mutation is expressed as a percent of wt VLP infectivity. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means. (B) Correlation between percent infectivity and fusion index is plotted for all N-glycosylation sites mutants. The cut off, represented by a dot line, shows no infectivity when fusion index is < 0.6.

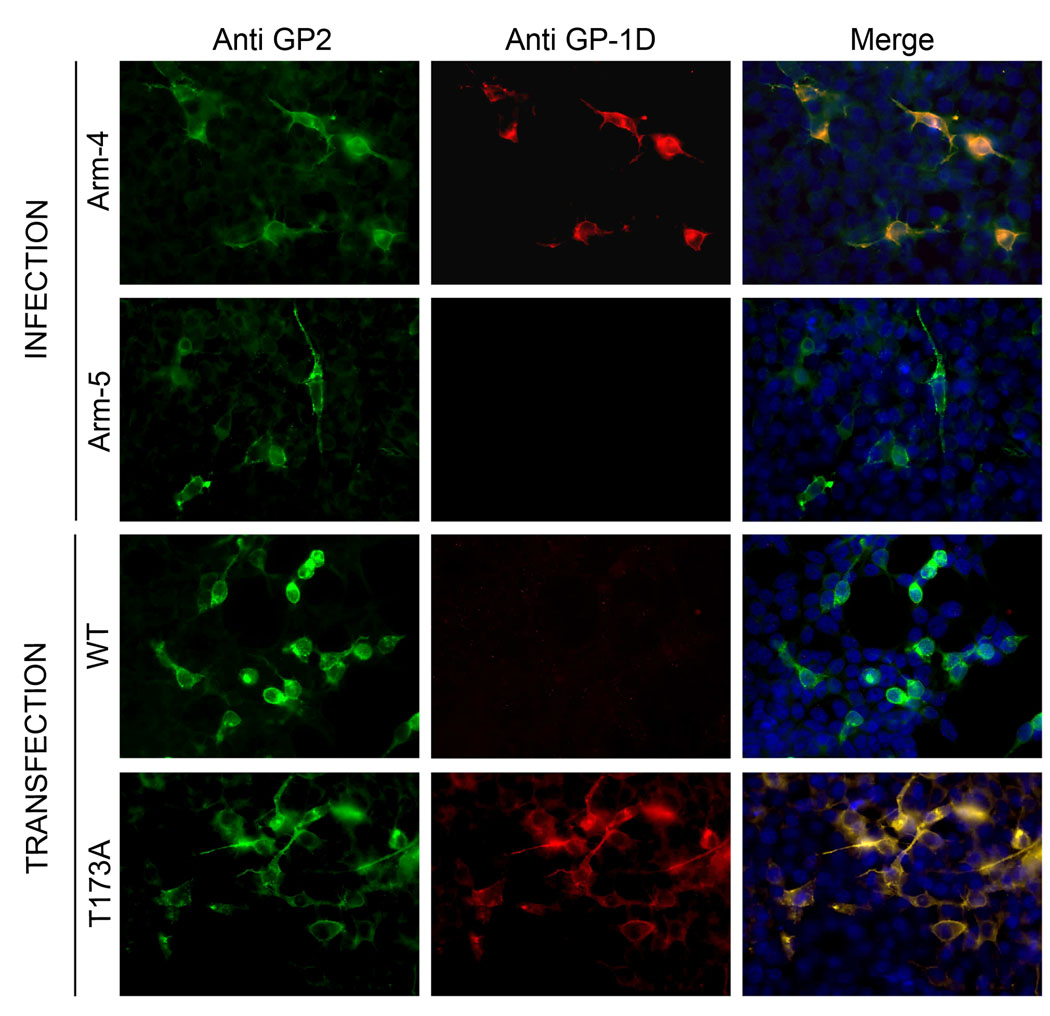

N-linked glycan at position 173 is responsible for masking epitope GP 1D

The isolates of LCMV used in our laboratory, Arm-5 and Arm-4, are two of the ten clones plaque-purified in 1981 from a parental stock of LCMV Armstrong (CA 1371), which was used to generated monoclonal antibodies (Buchmeier et al., 1980; Buchmeier et al., 1981). Published data from Wright et al. described that of these 10 clones, all possessed the major neutralizing epitope A but only 5 reacted with monoclonal antibodies specific for epitope GP-1D (Wright, Salvato, and Buchmeier, 1989). The nucleotide sequence of GP1 from Arm-5 (epitope A+D−) and Arm-4 (epitope A+D+) revealed two variations in GP1. These variants occurred at position 173, with a threonine in Arm-5 and an alanine in Arm-4, and at position 252 with a leucine in Arm-5 and a phenylalanine in Arm-4. However, the L252F variant was also found in the WE strain of LCMV. To determine if the amino acid change at position 173, which disrupts an N-glycosylation site, played a role in the masking of epitope GP-1D, this N-glycosylation site in Arm-5 was mutated and assayed for detection by immunofluorescence using a monoclonal antibody specific for epitope GP-1D (2–11-10), which is able to recognize Arm-4 but not Arm-5 (Fig. 6). As expected, cells infected with Arm-5 or cells transfected to express the wt GP from Arm-5 were negative for epitope GP-1D. On the contrary, cells infected with Arm-4 and cells transfected to express the N-glycosylation mutation T173A in Arm-5 GP were detected by the anti-epitope GP-1D antibody. This result demonstrated that the N-glycan linked on the Asp of this N-glycosylation site was responsible for the masking of the neutralizing epitope GP-1D on the Arm-5 clone.

Fig. 6.

Detection of epitope GP-1D. DBT cells infected with either LCMV Arm-4 or Arm-5 and transfected DBT with T173A or wt were submitted to detection of the epitope GP-1D using monoclonal antibody 2-11-10. GP2 was detected by the monoclonal antibody 83.6. Only the glycoproteins lacking the N-glycosylation site at position 173 were recognized by the anti epitope GP-1D monoclonal antibody 2-11-10.

DISCUSSION

LCMV Arm-5 glycoprotein possesses 9 potential N-glycosylation sites: 6 sites on GP1 and 3 sites on GP2 (Fig. 1A). Alignment of the glycoprotein protein sequences of 28 arenaviruses indicated that 3 N-glycosylation sites on GP2 were conserved in all members, except one. On the contrary, there was high diversity in the number and position of the N-glycosylation sites in GP1. Moreover, a similar pattern appeared for the Old World arenaviruses. The strict conservation of N-glycosylation sites suggested that the presence of N-linked glycans plays an important role in protein expression, processing, transport, and cell fusion or viral infectivity.

In the present study, we confirmed that all predicted N-glycosylation sites on GP1 were used by LCMV. Similar observations have been reported in Lassa fever virus (Eichler et al., 2006). Moreover, the LCMV glycoprotein was able to tolerate heterologous N-glycosylation sites inserted in GP1 or GP2. However, LCMV GP2 appeared to use only two of the three predicted N-glycosylation sites. These were suggested in 1990 based on digestion of Arm-4 GP2 by endoglycosidase (Wright et al., 1990). We conclude that the predicted site at position 373 was not used. Interestingly this site is part of the peptide GP-C 370–382 recognized by the monoclonal antibody anti GP2 83.6, which reacted with diverse Old and New world arenaviruses (Weber and Buchmeier, 1988). Our data also revealed that GP transport to the cell surface did not require proper GPC cleavage, as confirmed with the defective mutants T87A and S97A. N-glycosylations appeared to not be involved in GPC transport to the cell surface according to previous publications (Eichler et al., 2006; Kunz et al., 2003). However, our assays did not distinguish between properly and improperly formed GP complexes. As a result, GP transport to the cell surface was not predictive of changes in other functions. On the contrary, a strong relationship was observed between GPC processing, cell fusion and infectivity. This allowed the establishment of a functional hierarchy for GPC where each function is a requirement for the next: expression > GP1/GP2 cleavage > fusogenicity > infectivity. A defect in one function predicts defects in subsequent GP activities, while the ability to perform one function does not guarantee the ability to perform other downstream GP activities. A similar hierarchy was proposed for the signal peptide of LCMV GP (Saunders et al., 2007). This hierarchy allowed us to discuss our N-glycosylation sites mutation by hierarchic functional pattern. Interestingly, unprocessed GPC has a dominant negative effect in the fusion assay. This has already been reported for the Newcastle disease virus (Li et al., 1998). We suppose that unprocessed GPC is unable to undergo the structural modifications needed to perform fusion with host membranes. This can inhibit the fusogenicity of the remaining processed proteins.

We observed that mutants T87A, S97A and G104N abrogated virtually all GP functions. All induced a critical drop in GPC expression resulting in decreased processing. These data showed that the N-glycosylations at position 87 and 97 were required for wt-like levels of expression and were also necessary for processing. Moreover, N-glycosylation site at position 97 was conserved in all arenaviruses (Fig. 1B) supporting the importance of this N-glycosylation site. These mutations were also described in Lassa fever virus with similar defect in processing (Eichler et al., 2006). The detrimental effect of adding an N-linked glycan close to the N-term of GP1 suggested the region near amino acid 104 was required for expression. This decrease in expression could be the result of unfolded GPC protein, despite good surface expression. Indeed, the overproduction could produce enough GPC comparable to wt-like levels in surface expression.

The T234A mutation, despite very good expression, showed limited capacity to induce GP-mediate cell fusion resulting in no detectable VLP infectivity. This suggests that the last N-glycosylation on GP1, at position 234, was required for GP-mediated fusion. The presence of N-linked glycans has been shown to be necessary for budding and infectivity in LCMV (Wright et al., 1990) and syncytium formation in Measles virus (Malvoisin and Wild, 1994). Since this N-glycosylation site was conserved in 24/28 arenavirus glycoproteins we suppose that the N-linked glycan at position 234 plays a key role in GP-mediated fusion. On another hand, insertion in LCMV of a glycan at position 379/381 otherwise present in all arenaviruses excepted LCMV and Dandenong virus, led to a similar defect in GP-mediated fusion that resulted in loss of VLP infectivity. We therefore hypothesize that modification in this region could have an effect on LCMV GP-mediated fusion. Due to the natural presence of this glycan in all the arenavirus strains, except LCMV and Dandenong virus, we believe this is specific for LCMV and possibly Dandenong virus.

The S116A and T126A mutants localized on GP1 exhibited very low infectivity despite good expression, processing and fusion. Every function tested with GP alone was comparable to wt. This was true with both VLP infectivity and retroviral pseudotyping assay showing that this low infectivity was a direct consequence of N-glycosylation mutants S116A and T126A. Moreover, purification of VLP by ultracentrifugation through 20% sucrose allowed us to detect GP from VLP on Western blots for both mutants (data not shown). However the method was poorly reproducible and highly variable making quantification difficult. Nevertheless, the assay confirmed that we were not isolating “naked VLPs” that lacked GP. Nevertheless, we suppose that the level of incorporation into VLP of these mutants was lower than wt GP. Similar patterns were observed for both S398A and T403 mutants with a decrease in VLP infectivity but still less than 27% compare to the wt. Once again, GP alone mediated all the functions tested so lower levels of incorporation of the N-glycosylation mutants into VLP could explain the observed results.

Mutation T173A was designed to recreate the Arm-4 clone N-glycosylation variation in order to confirm that this N-linked glycan at position 173 was responsible for masking of epitope GP-1D in Arm-5. This mutant behaved like the Arm-4 clone, arguing that all functions were similar to the wt. This suggests that the second mutation described in the Arm-4 clone, leucine to phenylalanine at position 252, did not play a role in infectivity. In addition, our immunofluorescence data demonstrated a direct role for this N-glycan in the masking of epitope GP-1D. Masking of epitope by N-glycosylation has been shown in the case of HIV and influenza virus and may permit the characterization of neutralizing antibodies using an epitope-unmasking procedure (Ditzel et al., 1995; Munk et al., 1992).

The first predicted N-glycosylation site on GP2 present in all arenaviruses, was not found to be used. This point mutation was responsible for gain in all functions tested for GP, resulting in an increased infectivity compared to the wt. Increases in infection following mutation of a N-glycosylation site was described for the HCV glycoprotein (Delgrange et al., 2007) and the Foamy virus glycoprotein (Luftenegger et al., 2005) and was responsible for a higher infectious titer. However, in our case the increased functions were not linked to the presence of a glycan. This mutation presents a perfect hyperinfectious control for testing in recombinant LCMV.

In summary, our study shows that each N-linked glycan in the arenavirus glycoprotein is involved in GPC expression, GP-mediated fusion or infectivity. Further studies are needed to elucidate the role of these N-glycosylation mutants in a recombinant virus system. Interestingly, a recent publication on pandemic strains of influenza suggested a novel role for glycans in viral evolution and vaccine design (Wei et al. 2010). This work suggested that the 1918 pandemic virus evaded antibodies by mutating the tips of the glycoprotein to change the presentation of glycans. Surprisingly the 2009 pandemic strain reverted to a configuration similar to that of the original 1918 strain. This reinforces our idea that glycans are used as a cloud around the glycoprotein to mask epitopes on the viral glycoprotein from neutralizing antibodies. Further investigations using recombinant LCMV N-linked glycan mutants to enhance exposure of epitopes may facilitate vaccination against arenaviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and virus

DBT murine astrocytoma cells, BHK-21 hamster kidney fibroblast and HEK 293T human embryonic kidney cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The LCMV-Armstrong clone 4 (Arm-4) and clone 5 (Arm-5) were used throughout these studies (Wright, Salvato, and Buchmeier, 1989).

Plasmids and transfections

All point mutants were made from pC-GPC-Flag (LCMV Arm53b GPC) (Capul et al., 2007) by use of a QuikChange PCR mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Mutations were confirmed by sequencing. Each N-glycosylation site mutation was made in a full-length GPC gene. Plasmids expressing the LCMV L (pC-L), NP (pC-NP), and Z (pC-Z) proteins and T7 RNA polymerase (pC-T7) under the control of a modified chicken β-actin promoter, as well as minigenome (MG) under the control of a T7 promoter, have been previously described (Lee et al., 2002). All transfections were performed with fresh preparations of plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions, using 2.5µl Lipofectamine/µg plasmid DNA. Transfection medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 5% FBS at 5h post transfection.

Western blot

HEK 239T or DBT cells were collected 48h post transfection in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Hcl pH 8, 62.5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 1% NP-40 and 0.4% sodium deoxycholate [DOC]). Cell lysates were mixed with NuPAGE® LDS sample buffer completed with NuPAGE® sample reducing agent (Invitrogen) and boiled for 10 min. Lysates were then separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% powdered milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 0.2% Tween, for 1h at room temperature. Incubation with the primaries anti-GP2 monoclonal antibody 83.6 at dilution 1/100 and Anti-Caveolin-1, clone 7C8 mouse monoclonal at 4µg/ml (Upstate Cell Signaling) was performed overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed with PBS Tween and probed with an anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at dilution 1/1000 for 1 h at room temperature, and washed an additional three times. Membranes were developed by incubation with Immun-Star alkaline phosphatase substrate (Bio-Rad) then chemiluminescence observed with the Chemidoc™ XRS (Bio-Rad). Densitometry analysis was performed with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad) as follows. For each lane the densitometry was measured for the band corresponding to GPC, GP2 and the loading control caveolin. The total of GPC+GP2 or GP2-only were normalized using the loading control. The percentage of cleavage was calculated as follow: %cleavage = [(normalized density of the GP2 band) / (normalized density of the GPC+GP2 bands)] ×100. As examples, 0% cleavage means no GP2 band detected where 100% means no GPC band detected.

Flow cytometry

Transfected HEK 293T or DBT cells were carefully washed with cold PBS then blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA) 3% PFA 0.1% in PBS for 1h at 4°C. Cells were permeabilized by treating with 0.1% Triton X100 for 5 min at 4°C. Incubation was performed with anti-GP2 antibody 83.6 directly coupled to Alexa 488 at 1/100 overnight at 4°C, then washed carefully once. Cells were then detached by pipetting then washing 2 more times in 5ml round bottom tubes. Cells were finally fixed with 3.7% PFA and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACScalibur (BD biosciences). Data were analysed using FlowJo 8.8.6 software.

Immunofluorescence assay

HEK 293T or DBT cells were grown on cover slips, transfected as described previously then were washed with cold PBS and fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min. Cells were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS for 1h at RT. Cells were incubated with anti-GP2 antibody 83.6 directly coupled to Alexa 488 or anti epitope GP-1D 2–11-10, at 1/100 overnight at 4°C. Cells were visualized using a Nikon Elipse Ti microscope with NIS-Element AR 3.00 sp7 software.

VLP infectivity assay

HEK 293T cells were plated in 35-mm wells at 8×105 cells/well. After 24h cells were 70% confluent and were transfected with a mix of pC-NP (0.4 µg), pT7-MG (0.25 µg), pC-T7 (0.5 µg), pC-L (0.4 µg), pC-Z (0.5 µg), wt or mutant pC-GPC-Flag (0.4 µg). The amount of total plasmid DNA was brought to 3 µg final by empty vector. At 48 h post transfection, VLP-containing supernatants (2 ml) were harvested and clarified at 2000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Half of the supernatants were used to infect fresh monolayers of BHK-21 cells. After 4h adsorption with gentle rocking at 37°C, the inoculum was removed and LCMV Arm-4 was added at a multiplicity of infection of 3 to provide the viral trans-acting factors required for RNA replication and expression of the MG RNA (Lee et al., 2002) . After 3h adsorption, the inoculum was replaced by fresh media. At 48h post infection, BHK-21 cells were lysed and assayed for chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) expression.

CAT enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay to quantify VLP infectivity

CAT assays were done as described previously (Saunders et al., 2007). Briefly, cells were collected in PBS and whole-cell extracts were obtained by 3 freeze-thaw cycles. The concentration of CAT was measured using a CAT enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Roche Applied Science) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

DBT cell fusion assay

DBT cells were transfected with pC GPC-Flag containing each individual N-glycosylation mutant. At 48h post-transfection, cells were exposed to pH 5 buffered medium for 1h then returned to neutral pH for 1h. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with Giemsa. The extent of syncytium formation was quantified using representative images at 100X magnification. The following equation was used to calculate the fusion index (FI): FI = [1-(number of cells/number of nuclei)] (Saunders et al., 2007)

Production of retrovirus and percentage infectivity

HEK 293T cells at 70% confluency were cotransfected with 1.3µg of each plasmids pCgp, pCnBg and pC GPC-Flag with 10µl of Lipofectamine 2000. Plasmid pCgp is a packaging construct that encodes MuLV Gal-Pol (Han et al., 1998), and pCnBg is a retrovirus vector genome carrying a nuclear β-galactosidase reporter gene (Han et al., 1997). Determination of vector titer was performed as publish previously (Christodoulopoulos and Cannon, 2001). At 48h post-transfection supernatant from transfected HEK 293T cells containing the retroviruses was harvested. Serial dilutions of the vector supernatants were prepared, and 1 ml of each dilution was added to a fresh monolayer of cells with 8 µg/ml of Polybrene (Sigma). The titer was determined by staining overnight with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl- beta-D-galactopyranoside) at 48h post-transduction. Titer was determined by counting blue colonies in each well, which was normalized to wt LCMV GP and expressed as percentage of infectivity compared to the wt.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were generated using Prism 4 (GraphPad) software.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Juan Carlos de la Torre for providing the constructs for VLP assay. This work was supported by the NIH grant AI-065359 Pacific Southwest Regional Center of Excellence and the Post-baccalaureate research education program NIH GM-64126.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Cyrille J. Bonhomme, Email: cbonhomm@uci.edu.

Althea A. Capul, Email: acapul@uci.edu.

Elvin J. Lauron, Email: elauron@chori.org.

Lydia H. Bederka, Email: lbederka@uci.edu.

Kristeene A. Knopp, Email: kknopp@uci.edu.

Michael J. Buchmeier, Email: m.buchmeier@uci.edu.

References

- Agnihothram SS, Dancho B, Grant KW, Grimes ML, Lyles DS, Nunberg JH. Assembly of arenavirus envelope glycoprotein GPC in detergent-soluble membrane microdomains. J Virol. 2009;83(19):9890–9900. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00837-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amman BR, Pavlin BI, Albarino CG, Comer JA, Erickson BR, Oliver JB, Sealy TK, Vincent MJ, Nichol ST, Paddock CD, Tumpey AJ, Wagoner KD, Glauer RD, Smith KA, Winpisinger KA, Parsely MS, Wyrick P, Hannafin CH, Bandy U, Zaki S, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG. Pet rodents and fatal lymphocytic choriomeningitis in transplant patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(5):719–725. doi: 10.3201/eid1305.061269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton LL. LCMV transmission by organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1737. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc061706. author reply 1737-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton LL, Mets MB. Congenital lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection: decade of rediscovery. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(3):370–374. doi: 10.1086/321897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer WR, Popplau D, Garten W, von Laer D, Lenz O. Endoproteolytic processing of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein by the subtilase SKI-1/S1P. J Virol. 2003;77(5):2866–2872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.5.2866-2872.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrow P, Oldstone MB. Mechanism of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus entry into cells. Virology. 1994;198(1):1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briese T, Paweska JT, McMullan LK, Hutchison SK, Street C, Palacios G, Khristova ML, Weyer J, Swanepoel R, Egholm M, Nichol ST, Lipkin WI. Genetic detection and characterization of Lujo virus, a new hemorrhagic fever-associated arenavirus from southern Africa. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(5):e1000455. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier MJ, Lewicki HA, Tomori O, Johnson KM. Monoclonal antibodies to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus react with pathogenic arenaviruses. Nature. 1980;288(5790):486–487. doi: 10.1038/288486a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier MJ, Lewicki HA, Tomori O, Oldstone MB. Monoclonal antibodies to lymphocytic choriomeningitis and pichinde viruses: generation, characterization, and cross-reactivity with other arenaviruses. Virology. 1981;113(1):73–85. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Buchmeier MJ. Protein-protein interactions in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virology. 1991;183(2):620–629. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90991-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Henry MD, Borrow P, Yamada H, Elder JH, Ravkov EV, Nichol ST, Compans RW, Campbell KP, Oldstone MB. Identification of alpha-dystroglycan as a receptor for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and Lassa fever virus. Science. 1998;282(5396):2079–2081. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capul AA, Perez M, Burke E, Kunz S, Buchmeier MJ, de la Torre JC. Arenavirus Z-glycoprotein association requires Z myristoylation but not functional RING or late domains. J Virol. 2007;81(17):9451–9460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00499-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulopoulos I, Cannon PM. Sequences in the cytoplasmic tail of the gibbon ape leukemia virus envelope protein that prevent its incorporation into lentivirus vectors. J Virol. 2001;75(9):4129–4138. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4129-4138.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deibel R, Woodall JP, Decher WJ, Schryver GD. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in man. Serologic evidence of association with pet hamsters. JAMA. 1975;232(5):501–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgrange D, Pillez A, Castelain S, Cocquerel L, Rouille Y, Dubuisson J, Wakita T, Duverlie G, Wychowski C. Robust production of infectious viral particles in Huh-7 cells by introducing mutations in hepatitis C virus structural proteins. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 9):2495–2503. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82872-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Simone C, Buchmeier MJ. Kinetics and pH dependence of acid-induced structural changes in the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein complex. Virology. 1995;209(1):3–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Simone C, Zandonatti MA, Buchmeier MJ. Acidic pH triggers LCMV membrane fusion activity and conformational change in the glycoprotein spike. Virology. 1994;198(2):455–465. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzel HJ, Binley JM, Moore JP, Sodroski J, Sullivan N, Sawyer LS, Hendry RM, Yang WP, Barbas CF, 3rd, Burton DR. Neutralizing recombinant human antibodies to a conformational V2- and CD4-binding site-sensitive epitope of HIV-1 gp120 isolated by using an epitope-masking procedure. J Immunol. 1995;154(2):893–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler R, Lenz O, Garten W, Strecker T. The role of single N-glycans in proteolytic processing and cell surface transport of the Lassa virus glycoprotein GP-C. Virol J. 2006;3:41. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SA, Graham MB, Kuehnert MJ, Kotton CN, Srinivasan A, Marty FM, Comer JA, Guarner J, Paddock CD, DeMeo DL, Shieh WJ, Erickson BR, Bandy U, DeMaria A, Jr, Davis JP, Delmonico FL, Pavlin B, Likos A, Vincent MJ, Sealy TK, Goldsmith CS, Jernigan DB, Rollin PE, Packard MM, Patel M, Rowland C, Helfand RF, Nichol ST, Fishman JA, Ksiazek T, Zaki SR. Transmission of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus by organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(21):2235–2249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Cannon PM, Lai KM, Zhao Y, Eiden MV, Anderson WF. Identification of envelope protein residues required for the expanded host range of 10A1 murine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1997;71(11):8103–8108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8103-8108.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Zhao Y, Anderson WF, Cannon PM. Role of variable regions A and B in receptor binding domain of amphotropic murine leukemia virus envelope protein. J Virol. 1998;72(11):9101–9108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9101-9108.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius A, Aebi M. Intracellular functions of N-linked glycans. Science. 2001;291(5512):2364–2369. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klewitz C, Klenk HD, ter Meulen J. Amino acids from both N-terminal hydrophobic regions of the Lassa virus envelope glycoprotein GP-2 are critical for pH-dependent membrane fusion and infectivity. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 8):2320–2328. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82950-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz S, Edelmann KH, de la Torre JC, Gorney R, Oldstone MB. Mechanisms for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein cleavage, transport, and incorporation into virions. Virology. 2003;314(1):168–178. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Perez M, Pinschewer DD, de la Torre JC. Identification of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) proteins required to rescue LCMV RNA analogs into LCMV-like particles. J Virol. 2002;76(12):6393–6397. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.6393-6397.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Sergel T, Razvi E, Morrison T. Effect of cleavage mutants on syncytium formation directed by the wild-type fusion protein of Newcastle disease virus. J Virol. 1998;72(5):3789–3795. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3789-3795.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luftenegger D, Picard-Maureau M, Stanke N, Rethwilm A, Lindemann D. Analysis and function of prototype foamy virus envelope N glycosylation. J Virol. 2005;79(12):7664–7672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7664-7672.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malvoisin E, Wild F. The role of N-glycosylation in cell fusion induced by a vaccinia recombinant virus expressing both measles virus glycoproteins. Virology. 1994;200(1):11–20. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick JB, Fisher-Hoch SP. Lassa fever. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;262:75–109. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56029-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk K, Pritzer E, Kretzschmar E, Gutte B, Garten W, Klenk HD. Carbohydrate masking of an antigenic epitope of influenza virus haemagglutinin independent of oligosaccharide size. Glycobiology. 1992;2(3):233–240. doi: 10.1093/glycob/2.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman BW, Adair BD, Burns JW, Milligan RA, Buchmeier MJ, Yeager M. Complementarity in the supramolecular design of arenaviruses and retroviruses revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and image analysis. J Virol. 2005;79(6):3822–3830. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3822-3830.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paweska JT, Sewlall NH, Ksiazek TG, Blumberg LH, Hale MJ, Lipkin WI, Weyer J, Nichol ST, Rollin PE, McMullan LK, Paddock CD, Briese T, Mnyaluza J, Dinh TH, Mukonka V, Ching P, Duse A, Richards G, de Jong G, Cohen C, Ikalafeng B, Mugero C, Asomugha C, Malotle MM, Nteo DM, Misiani E, Swanepoel R, Zaki SR. Nosocomial outbreak of novel arenavirus infection, southern Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(10):1598–1602. doi: 10.3201/eid1510.090211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CJ, Zaki SR. Role of the endothelium in viral hemorrhagic fevers. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(5 Suppl):S268–S273. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones-Kochs MI, Buonocore L, Rose JK. Role of N-linked glycans in a human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein: effects on protein function and the neutralizing antibody response. J Virol. 2002;76(9):4199–4211. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4199-4211.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders AA, Ting JP, Meisner J, Neuman BW, Perez M, de la Torre JC, Buchmeier MJ. Mapping the landscape of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus stable signal peptide reveals novel functional domains. J Virol. 2007;81(11):5649–5657. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02759-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla N, de la Torre JC. Arenavirus diversity and evolution: quasispecies in vivo. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;299:315–335. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26397-7_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara K, Kitame F, Nishimura H, Nakamura K. Operational and topological analyses of antigenic sites on influenza C virus glycoprotein and their dependence on glycosylation. J Gen Virol. 1988;69(Pt 3):537–547. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-3-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber EL, Buchmeier MJ. Fine mapping of a peptide sequence containing an antigenic site conserved among arenaviruses. Virology. 1988;164(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90616-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei CJ, Boyington JC, Dai K, Houser KV, Pearce MB, Kong WP, Yang ZY, Tumpey TM, Nabel GJ. Cross-neutralization of 1918 and 2009 influenza viruses: role of glycans in viral evolution and vaccine design. Sci Transl Med. 2(24):24ra21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KE, Salvato MS, Buchmeier MJ. Neutralizing epitopes of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus are conformational and require both glycosylation and disulfide bonds for expression. Virology. 1989;171(2):417–426. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KE, Spiro RC, Burns JW, Buchmeier MJ. Post-translational processing of the glycoproteins of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virology. 1990;177(1):175–183. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90471-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss DF, Wagner G. The structural role of sugars in glycoproteins. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1996;7(4):409–416. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York J, Dai D, Amberg SM, Nunberg JH. pH-induced activation of arenavirus membrane fusion is antagonized by small-molecule inhibitors. J Virol. 2008;82(21):10932–10939. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01140-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]