Rheumatoid Arthritis

Introduction

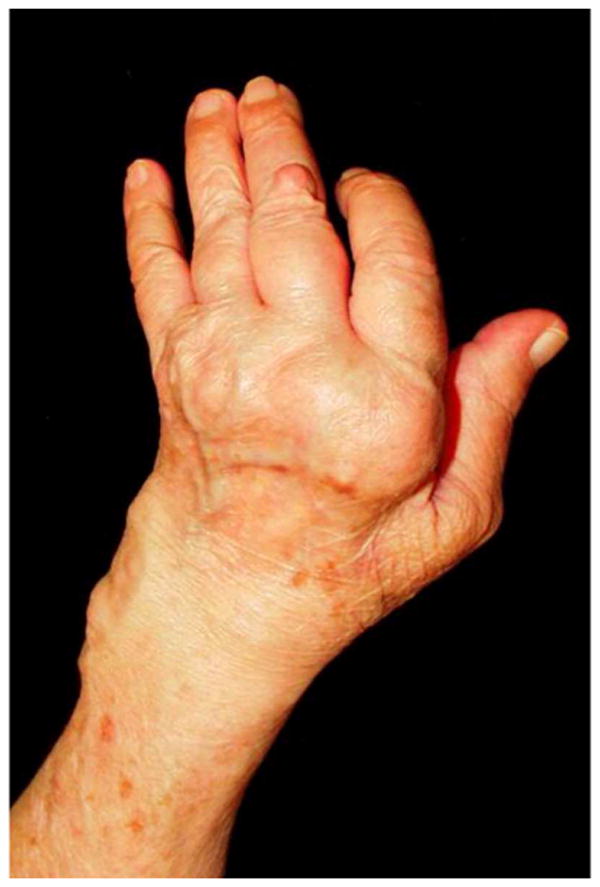

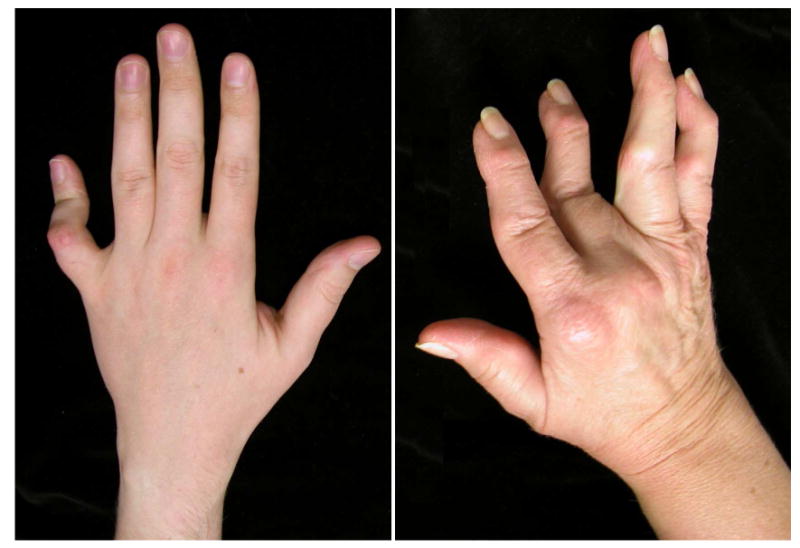

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a progressively destructive disease that affects 1% of the American population (1). The systemic manifestations can be severe and over 70% of rheumatoid patients develop hand problems that are painful and disabling. Gradual loss of hand function in RA patients affects their ability for self-care and interferes with their productivity in society. The prominent hand deformity can create social stigma for the RA patients (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

This photograph depicts the severely deformed rheumatoid hand including: (1) extensor tenosynovitis over the MCP joints, (2) ulnar deviation of the digits, (3) boutonniere deformity of the thumb, and (4) collapse of the carpus.

The RA patient presents to a surgeon searching for functional gain, pain relief, or aesthetic improvement (2). Whether hand surgical procedures can fulfill the patients' expectations is debatable. The lack of rigorously conducted outcomes studies to support the effectiveness of hand surgery in RA patients creates persistent disagreements between hand surgeons and rheumatologists towards the recommendations for RA hand reconstruction (3). There are significant variations in clinical management based on gender and regional practice that further compound the issue (4). The continuing improvement in the medical management of RA has markedly decreased the incidence of RA hand surgery. Because of the complexity of hand deformities in RA, it is important that surgeons and rheumatologists have a clear understanding of the goals and expectations of hand surgical procedures in an effort to provide a rational strategy for the overall hand rehabilitation program. The purpose of this chapter is to share our extensive experience in RA hand surgery in order to provide a clear discussion of the indications and outcomes of its practice.

Pathophysiology

RA is a chronic, inflammatory autoimmune disease that causes joint inflammation, cartilage destruction, and ligament weakness. RA is further characterized by the formation of pannus, caused by synovial inflammation in areas of increased vascularity. The pannus invades into terminal vessels resulting in soft tissue ischemia and stretching of adjacent, already weakened structures. Activated neutrophils from the pannus release lysosomal enzymes and free radicals destroy the articular surfaces. These destructive processes change the anatomy of the hand, leading to a gradual loss of function.

Treatment

First-line treatment for the RA hand aims to control the systemic disease. Any surgical intervention is futile without controlling the systemic inflammation, as surgical repairs cannot withstand the inflammatory challenge of uncontrolled disease. Hand surgeons must work closely with rheumatologists when contemplating surgical treatment. Anti-inflammatory medications are weaned as tolerated to decrease the risk of wound healing complications. Working closely with certified hand therapists in the pre- and post-operative periods is necessary to ensure the best outcomes. The first step in any planned surgical intervention is early evaluation by a hand surgeon experienced with RA to develop a treatment program that minimizes the incidence of uncorrectable late deformities.

RA hand surgery is divided into prophylactic and reconstructive procedures. Prophylactic procedures include tenosynovectomy, joint synovectomy, and tendon rebalancing. These prophylactic procedures may delay the destructive RA processes, extending the useful lifespan of tendons and joints. Reconstructive procedures are often more complex than prophylactic procedures. Reconstructive procedures include arthrodesis, arthroplasty and tendon transfer. The surgical treatment algorithm depends on the individual patient, the involved joints, and the desired outcome. Regardless of the operative procedure, the surgeon must discuss the limitations and risks of surgery with the patient to avoid unrealistic post-operative expectations. RA hand surgery never restores normal function.

Pre-operative Evaluation

During the initial consultation, the surgeon should understand the patient's concerns regarding hand function and hand appearance. Deformity alone is not an indication for proposing surgical treatment. Rather, the surgeon ought to assess the patient's hand impairment in their work and daily activities to render recommendations whether surgical treatment can be beneficial. Many RA patients can adapt to their hand deformities over time. The challenge for the hand surgeon is to evaluate whether the surgical intervention can enhance patient function. The surgeon should have sufficient prescience to recommend procedures that may prevent the development of future deformities. Some patients may also be concerned about the appearance of the deformed hand. Enhancing the appearance of RA hand may have unrecognized benefit to the patients' self-esteem.

An experienced RA surgeon will consider the priority of reconstruction. For example, patients should undergo lower extremity procedures first to avoid the stress from crutches or walker on the reconstructed upper limbs. In addition, proximal joints should be reconstructed before distal joints. A destroyed elbow will hamper wrist and hand function. The elbow should be treated first, followed by the wrist and the hand. Because radial deviation of the wrist will cause ulnar subluxation of the MCP joints, wrist deformity is corrected before undertaking MCP joint reconstruction.

Three view radiographs of the hands and wrists are mandatory to evaluate radiographic changes in the joints. The amount of articular or bony destruction seen on radiograph does not necessarily correlate with patients' complaints. Often, patients with minimal wrist pain have advanced wrist collapse on radiographs. Preoperative evaluation of the neck and cervical spine is essential because a substantial proportion of RA patients have atlanto-axial subluxation. Instability of the cervical spine should be evaluated prior to having surgical procedures. Ideally, regional anesthesia is preferred, but some patients may require general anesthesia.

Prophylactic Procedures

Prophylactic surgical procedures in the rheumatoid patient include tenosynovectomy, joint synovectomy, and tendon rebalancing. Tenosynovectomy is the surgical removal of inflamed synovial tissues surrounding a tendon, whereas joint synovectomy is the removal of inflamed synovial tissue within a joint. Excision of inflamed synovial tissue is ideally performed prior to irreversible joint destruction. Removing inflamed and hypertrophic peritendinous synovial tissues can enhance tendon gliding and improve finger motion. Excising bulging synovial tissues from joints should decrease pain. Because tendons and ligaments around joints may be stretched from hypertrophic synovium, tendon rebalancing can restored the anatomic positions of the displaced tendons and ligaments.

Tenosynovectomy

Inflammation of the synovial lining of extensor tendons leads to swelling over the dorsal hand and wrist. These synovial tissues can invade the tendons and cause them to rupture. Extensor tenosynovectomy is recommended when synovitis persists for 3-6 months despite aggressive medical management. Extensor tendon rupture should be differentiated from other causes of extension lag including: (1) extensor tendon subluxation at the MCP joints, (2) MCP joint dislocations, and (3) posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) palsy. When the extensor tendon is subluxed between the head of the metacarpals, it acts as a MCP joint flexor instead of an extensor. The course of the extensor tendons is seen ulnar to the head of the metacarpals. When the fingers are extended passively, the subluxed extensor tendons can maintain partial finger extension. Joint subluxation is marked by prominent metacarpal heads and the proximal phalanges resting volar to the metacarpals. Radiographs will confirm the subluxation. Inability to extend any of the digits or thumb suggests a posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) injury attributable to inflammation around the nerve at the radiohumeral joint.

A dorsal longitudinal incision is used for extensor tenosynovectomy to expose all extensor compartments. Following tenosynovectomy, the extensor retinaculum can be split in half transversely. One half is place under the tendons to shield the extensor tendons from the eroded wrist bones and the other half is placed over the tendons to prevent bowstringing. Figure 2 demonstrates an example of extensor tenosynovectomy. The terminal branch of the PIN, which rests on the floor of the 4th extensor compartment, can be excised to denervate the wrist joint if there is associated wrist pain.

Fig 2.

Intra-operative photographs demonstrating extensor tenosynovitis with rice bodies (left), and subsequent removal of the extensor tenosinovium (right).

At the MCP joints, a tendon rebalancing procedure is often combined with MCP joint synovectomy. The stretched radial sagittal band is opened to provide access to the joint for synovectomy. The radial sagittal band is then imbricated to relocate the extensor tendons. The deforming ulnar lateral band can be divided distally from the index, middle and ring fingers to transfer to the extensor tendons of the middle, ring and little fingers to maintain the extensor tendon in the central position. This intrinsic transfer procedure is used when the MCP joint is still passively reducible by transferring the tight ulnar intrinsic tendons to bring the fingers back into alignment. The abductor quinti minimi should be released because it is often tight and draws the little finger ulnarly. The index finger is realigned by tightening the radial sagittal band, as there is no adjacent finger to provide the ulnar lateral band. Radial deviation of the wrist can contribute to ulnar deviation of the fingers. Transferring the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) tendon, which inserts over the index metacarpal, to the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) can balance the wrist. Not only can this transfer remove the deforming radial force on the wrist, the ECRL transfer can elevate the often volarly subluxed ECU tendon and provide a more ulnar, dorsal pull to the wrist.

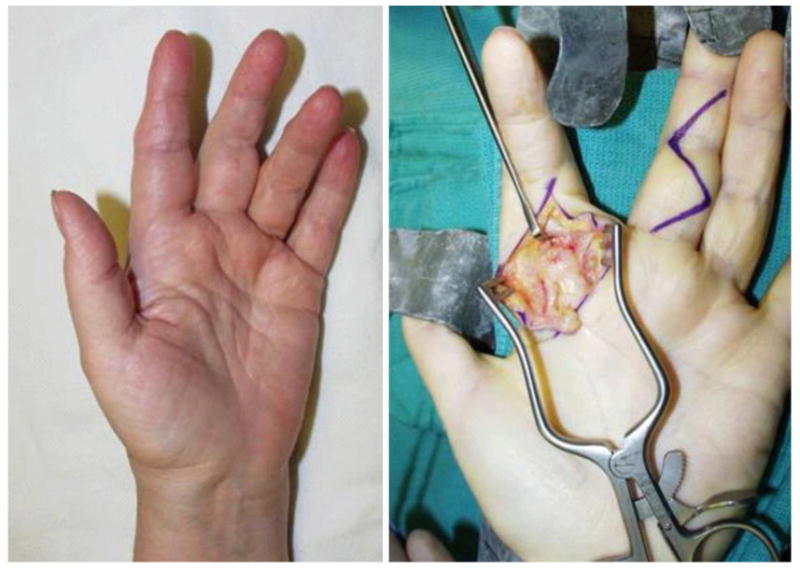

The flexor system can also be affected by synovitis. The increased bulk in the flexor tendon sheath causes less active flexion than passive flexion of the fingers. The joints in the fingers are still mobile and can be passively flexed, but the inflamed flexor tendons are not able to pull the fingers actively into flexion. In addition, sufficient synovial tissue build-up in the flexor tendons can cause triggering of the fingers at either the A1 pulley or the carpal tunnel. Unlike the traditional “trigger finger,” whereby release of the A1 pulley is the preferred treatment, in RA trigger, it is recommended that the A1 pulley is preserved to support the MCP joints from ulnar deviating forces. The preferred method is removal of the synovial tissue and excision of a slip of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon to decrease the volume within the pulley system (Fig 3). Carpal tunnel release treats the wrist trigger and alleviates median nerve compression.

Fig 3.

A patient presenting with flexor tenosynovitis and digital triggering secondary to increased mass at the A1 pulley (left) along with the corresponding intra-operative photograph (right).

Joint Synovectomy

Intra-articular inflammation of the wrist, MCP, or PIP joints causes pain and decreases motion. Synovitis leads to laxity of the joint capsule, collateral ligaments, and volar plate. The continued stretching of the support ligaments results in tendon imbalances. The rationale for early joint synovectomy is to remove the diseased synovium prior to articular cartilage destruction and supporting ligament attenuation. For MCP joint synovitis, six to nine months of medical management is recommended prior to considering surgery. Persistent, localized joint synovitis may benefit from synovectomy, but the long-term benefit of surgery in ameliorating joint destruction has not been shown in well conducted trials.

The surgeon should discuss with the patient pre-operatively that these are prophylactic and not curative procedures. While the literature suggests synovectomy does provide some palliation of symptoms, there is still limited outcomes data on the effectiveness of these procedures. Perceptions of the success rate of these procedures differ between rheumatologists and hand surgeons (5). The introduction of new RA medications has been quite effective in treating synovitis and the rate of synovectomy procedures is decreasing.

Reconstructive Procedures

Wrist

The wrist is the earliest and most frequent site of RA hand disease. Destruction of the ulnar carpal ligamentous structures leads to a syndrome called “caput ulna syndrome.” This “ulnar head syndrome” is marked by dorsal subluxation of the distal ulna. The inflammation of the dorsal soft tissue envelope leads to weakening of the dorsal supporting structures. Supination of the carpus subsequently occurs due to loss of dorsal support and the volar displacing force of the flexor tendons. This volarly displacing force is exacerbated by volar subluxation of the ECU. Inflammation of the radial sided structures further deforms the wrist. Unopposed pull of the radial wrist extensors leads to radial deviation of the metacarpals and a resultant ulnar deviation of the phalanges. In addition, the loss of dorsal soft tissue support leads to dorsal dislocation of the ulnar head and weakening of the distal radial-ulnar joint (DRUJ). In advanced disease, there is complete collapse of the wrist with volar dislocation of the carpus and dissociation of the DRUJ. Radiographs are often worse than the clinical picture. Treatment is targeted at patient concerns and not radiographic findings. Operative interventions for the RA wrist are mainly reconstructive. Total synovectomy is impossible because access to the many recesses in the wrist joint is quite difficult and partial synovectomy alone provides limited long-term benefit.

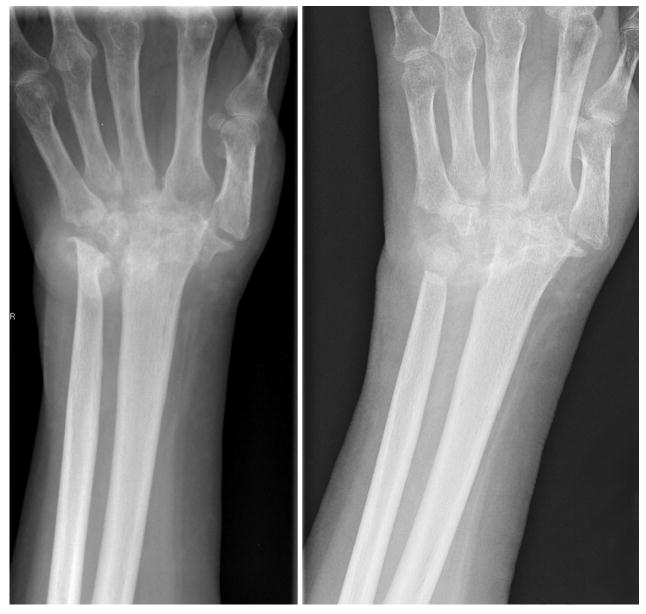

The wrist is a complex joint and surgical interventions need to address the DRUJ, radiocarpal joint, and midcarpal joint. For moderate disease in a patient with limited functional demand, distal ulna resection, or Darrach procedure, is beneficial. An incision is made over the distal ulna to expose the 6th compartment. The sheath over the distal ulna is incised and an oblique osteotomy is made over the neck of the ulna head (Fig 4). Synovectomy of the DRUJ and relocation of the ECU are performed concurrently. Alternatively, ECRL can be transferred to ECU to improve alignment. The forearm is now supinated to seat the distal ulna stump volarly. The dorsal capsule is closed tightly over the distal ulna stump. This procedure is not advised when the wrist is unstable because the lack of ulna head support may lead to ulnar subluxation of the carpus. In these cases, the Suave-Kapandji procedure is preferred. Instead of resection of the distal ulna, a segmental resection is performed proximally. The distal ulnar remnant is then fused to the sigmoid notch of the distal radius. Arthrodesis is performed using either K-wires or an interfragment screw.

Fig 4.

Severe ulnar head destruction (left) is treated by distal ulnar resection (right).

Radiocarpal articular wear requires arthroplasty or arthrodesis (Fig 5). Both procedures are indicated for deformity and instability that interfere with function or cause persistent pain. Prerequisite requirements for arthroplasty include good pre-operative wrist motion, functional wrist tendons, and good bone stock. In addition, adequate soft tissue is necessary to stabilize the wrist implant. Wrist arthrodesis is a predictable procedure and has a low complication rate. It is contraindicated in patients with severe shoulder and elbow diseases because patients may not be able to adapt to loss of motion in all three joints. Compared to arthrodesis, the post-operative rehabilitation program for arthoplasty is generally more difficult and is associated with higher risk of complications. The wrist mobility with arthroplasty is traded for the predictability with arthrodesis. Older methods of arthroplasty included the use of silicone or metal/polyethylene implants. An expanding number of total wrist replacement systems are increasing reconstructive options (6). Complications of wrist arthroplasty include fracture, infection, implant failure, implant dislocation, and implant loosening. For patients with bilateral wrist problem, arthrodesis is recommended in the dominant hand to maintain stability for gripping and power. The non-dominant hand is treated with arthroplasty to maintain some joint motion needed for self-hygiene. Destruction of the radiocarpal joint with preservation of the midcarpal joint may be treated with limited arthrodesis, which maintains about 25-50% of wrist motion through motion at the midcarpal joint.

Fig 5.

Surgical treatment options of the rheumatoid wrist includes arthodesis using Steinmann pins (left) or plating (center). Alternatively, prosthetic total wrist arthroplasty (right) can be performed.

Metacarpophalangeal joint

The metacarpophalangeal joint is the key joint for finger function. When we grip an object, the arc of motion is initiated at the MCP joint, then the PIP and DIP joints. Therefore, motion at the MCP joints of the fingers must be maintained for adequate hand function. The cam design of the MCP joint is stable in flexion during grip because of tightening of the collateral ligaments but is mobile in extension to manipulate objects. The typical ulnar deviation of the MCP joints is postulated to result from the following causes. First, the flexor and extensor tendons approach the MCP joints over the ulnar sides leading to a natural tendency for ulnar deviation with extension. Second, the normal pinch forces further direct the phalanges ulnarly. Third, radial deviation of the wrist and metacarpals in the RA hand combined with radial sagittal band attenuation leads to further ulnar shifting of the extensor tendons. These factors contribute to gradual tightening of the ulnar intrinsic tendons resulting in ulnar and volar subluxation at the MCP joints.

The RA patient with minimal pain and good hand function is best treated without an operation. When synovectomy is not applicable due to joint destruction, MCP arthroplasty should be considered. Traditional arthroplasty is performed with a silicone implant (Fig 6). After removing the diseased joints, the silicone spacer implant is inserted. The silicone implants are easy to place but fracture of the implants are not uncommon. The crucial part of the operation is to centralize the extensor tendons by stabilizing the radial ligament support. One must correct radial wrist deformity prior to MCP arthroplasty to avoid persistent ulnar forces on the reconstructed MCP joints. Following MCP arthroplasty, patients report significant improvement in function, aesthetic appearance, and overall satisfaction (7).

Fig 6.

Preoperative radiographs demonstrating MCP disease with joint destruction and subluxation (left). Following Swanson arthroplasty and realignment procedures, the hand is closer to a normal posture (right).

Interphalangeal joints

Digital deformities in the rheumatoid hand are either swan-neck or boutonniere's deformities. Swan-neck deformity is defined by hyper-extension of the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) and flexion of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) (Fig 7). The functional consequence of a swan-neck deformity is an inability to grasp objects because of hyperextension of the PIP joint. There are four initiating causes for a swan-neck deformity. First, extensor rupture at the terminal insertion creates a mallet finger that can progress to hyperextension of the PIP joint as the extensor tendon migrates proximally to increase the extensor force over the PIP joint. Second, PIP synovitis leads to volar plate laxity. Third, FDS tendon rupture at its insertion at the PIP joint leads to increased extensor force at the PIP joint. Lastly, intrinsic tendon tightness from MCP joint dislocation hyperextends the PIP joint. Initially, the deformity is correctable and soft tissue reconstruction may correct the deformity. Overtime, the deformity may become fixed and secondary joint contracture and articular wear may require joint procedures such as arthroplasty or arthrodesis.

Fig 7.

A swan-neck deformity of the middle finger with hyperextension of the PIP and flexion of the DIP is shown on the left. For comparison, a boutonniere's deformity of the small finger with flexion of the PIP and hyperextension of the DIP is shown on the right.

To determine treatment for flexible swan-neck deformity, one should understand the etiology of the deformity. For example, if the deformity is because of intrinsic tendon tightness and MCP joint subluxation, cross-intrinsic transfer (for mild subluxation) or resection arthroplasty will correct the problem. If the problem is at the PIP joint, providing more flexion force to the PIP joint can be helpful. For example, a slip of the FDS tendon can be divided proximally and sutured to the A1 pulley or to the metacarpal to prevent hyperextension of the PIP joint. Alternatively, the ulnar slip of the lateral band can be detached proximally and rerouted volar to the Cleland's ligament so that it is now volar to the axis of the PIP joint. By securing the lateral band to the bone, hyperextension is prevented and the deformity is corrected. If the problem arises from the DIP joint, then DIP joint fusion is the most predictable procedure.

The boutonniere's (or button hole) deformity has only one cause, which is rupture of the central extensor tendon over the PIP joint. The head of the proximal phalanx can “button hole” through the ruptured extensor tendon. In this deformity, the MCP joint is hyperextended, the PIP joint is flexed, and the DIP joint is hyperextended (Fig 7). The hypertrophic synovium at the PIP joint stretches the central extensor tendon. Secondary changes include volar displacement of the lateral bands and tightening of the oblique retinacular ligament, which hyperextend the DIP joint. Compensatory MCP hyperextension occurs because the patient tries to extend the fingers to get around objects. Early synovectomy may prevent the secondary changes. When secondary changes occur and the joint can still be reduced, terminal tenotomy will increase the tension over the PIP joint and correct the deformity. The DIP joint can still extend via the oblique retinacular ligament. If the joint is destroyed, the choices are limited to arthroplasty or arthrodesis.

Patients with boutonniere's deformity can often compensate for the deformity. Power grip is retained due to the flexion deformity at the PIP joint. Surgical correction may rob the patient of the ability to fully flex the PIP joints, resulting in loss of power grip in the ulnar digits Therefore, the decision to proceed with surgery on an ulnar-sided boutonniere's deformity must be considered carefully. Boutonniere's deformity is exceeding difficult to treat. Although the deformity is unsightly, patients can often adapt. In contrast, swan-neck deformity is easier to treat because patients often have an inability to grasp objects due to the extension posture at the PIP joints. Thus, the outcomes for treating a swan-neck deformity are better than boutonniere's deformity.

Thumb

Thumb deformities in the rheumatoid hand can be considered as boutonniere or swan-neck deformities, although the thumb having two phalanges is different from the fingers. In thumb boutonniere deformity, the MCP joint is flexed and the IP joint hyperextended. Thumb boutonniere deformity occurs from MCP joint synovitis leading to attenuation of extensor pollicis brevis (EPB), which inserts at the proximal phalanx. Similarly, the distension of the MCP joint stretches the extensor hood and causes volar subluxation of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon, which now flexes the MCP joint. For passively correctable disease, the treatment is synovectomy and rerouting of the EPL to extend the MCP joint. If the MCP joint deformity becomes fixed, MCP arthrodesis should be performed if the carpometacarpal joint (CMC) and IP joints are functional.

In swan-neck deformities, the deformity starts at the CMC joint. Radial and dorsal subluxation of the CMC joints results in an adduction contracture of the metacarpal. Compensatory MCP joint hyperextension occurs. CMC arthroplasty and volar tenodesis of the MCP joint (to correct for the compensatory MCP joint hyperextension) is recommended unless damage to the MCP joint is severe. In these cases, MCP arthrodesis is performed.

Tendon rupture

Medical and surgical management of tenosynovitis can prevent tendon rupture. Unfortunately, many RA patients do not present to a hand surgeon until tendon rupture has already occurred. An examination of a patient with extensor tendon lag should be able to differentiate between tendon rupture and other etiologies such as MCP joint subluxation or extensor tendon dislocation. The junctura between extensor tendons may still extend the ring or little fingers, if the rupture is proximal, but the patient may lack the final 10-20 degrees of MCP joint extension. In planning reconstruction, one should also treat the underlying causes of extensor tendon rupture by removing the infiltrating synovial tissues or by excising a prominent arthritic distal ulna. For ruptured flexor tendons, one should debride the volarly-subluxed distal scaphoid. When performing tenosynovectomy, the surgeon should always consider the possibility of finding ruptured tendons encased by the synovial tissues. The patient should be informed that tendon reconstructive procedures may be necessary as part of the synovectomy.

Tendon ruptures can be reconstructed by primary repair, tendon transfer, or tendon grafting. For a single tendon rupture that is detected early, it is theoretically possible to perform primary repair. However, the tendon quality is generally poor because the ends of the tendon are frayed from inflammation and attrition. Extensor tendon ruptures occur in the little finger first and then progress radially (Fig 8). The Vaughn-Jackson syndrome refers to the little finger extensor tendon rupture from a prominent, eroded distal ulna. Both the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) and extensor digiti minimi (EDM) of the little finger must rupture to develop an extension lag. It is often difficult to detect the rupture because the onset may be insidious and patients may still able to extend the little finger through the junctura attachment to the ring finger. When the little finger extensor is ruptured, the distal end can be attached to the ring finger. For ruptures of the ring and little fingers, attachment of the little finger extensor tendon to the intact middle finger will cause excessive ulnar deviation of the little finger. The senior author's preference is to transfer the extensor indicis proprius (EIP) tendon to power both the ring and little fingers. For ruptures of middle, ring and little fingers, the middle finger can be attached to the EDC of the index while the EIP can power the ring and little fingers. For rupture of all four finger extensor tendons, which is quite uncommon and is an unacceptable neglect by the patient and the physician, one can use the FDS tendons for the middle and ring fingers to power the extensors.

Fig 8.

This patient initially presented with loss of small and ring finger extension (left). Tendon rupture was found intra-operatively (middle). Following tendon transfer, the patient regained full extension.

On the flexor side, the most common tendon to rupture is the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) from abrasion over the volarly-displaced scaphoid. This lesion is also known as the Mannerfelt's lesion. FPL rupture may be overlooked because it tends to occur in an already non-functional thumb. Tendon grafting is used to repair FPL if the rupture is detected within 4-6 weeks before myostatic contracture of the FPL muscle hinders recovery of muscle function. In late presentation, brachioradialis or FDS of the index finger are ready donors for transfer to the FPL.

Summary

The care of the rheumatoid patient is complex and challenging. One should always inquire the patient about his/her needs when planning reconstruction. Deformity is not an indication for reconstruction because patients can often compensate for their deformity. The rheumatologists must also be engaged into the discussion about reconstruction. They can be particularly helpful in pre- and post-operative management of the patients' medications. An informed patient with regards to outcomes and complications is a patient who will derive the maximum benefit from a well-conceived surgical treatment program (8).

Osteoarthritis

Introduction

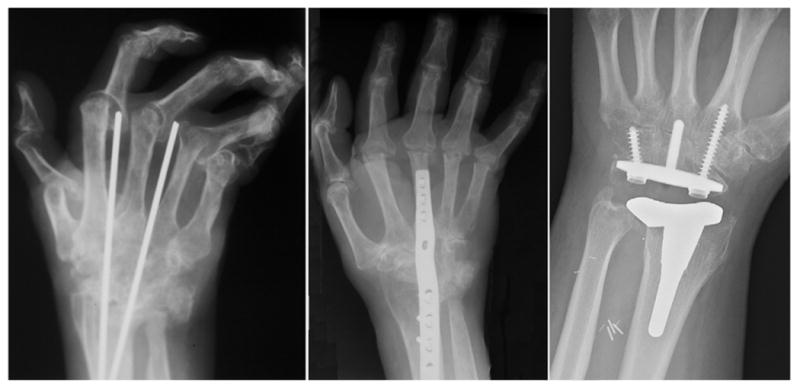

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the hand clinically affects 3% to 7% of adults (9). Elderly women are more likely to have hand involvement when compared to men. The CMC joint of the thumb and the IP joints of the digits are most frequently affected. OA is characterized by degradation of cartilage resulting in joint destruction and osteophyte formation (Fig 9). There appears to be a genetic component to OA in the development of hand disease. The underlying etiology is repetitive trauma inducing local chondrocytes to release degradative enzymes that damage the cartilage. In contrast to RA, OA has less inflammatory reaction in the joints. The initial treatment of OA is medication and therapy. Steroid injection into affected joints can provide short-term relief. Repeat injections, however, carry a cumulative risk of weakening the soft tissue and may cause thinning and hypopigmentation of the skin.

Fig 9.

These radiographs highlight the OA thumb with CMC destruction (left) and the subsequent post-operative radiograph following trapeziectomy and ligament reconstruction (right).

Treatment

Pre-operative Evaluation

Patients with OA may exhibit classic Heberden's and Bouchard's nodes located at the DIP and PIP joints respectively. Early radiographic findings include joint space narrowing and presence of osteophytes. Subchondral cyst and sclerosis are signs of more advanced disease. Symptom severity does not always correlate with radiographic findings; therefore, interventions should be based on patients' complaints. A full medical work-up is necessary prior to surgery given the multiple co-morbidities often seen in the typical elderly OA patient.

Operative Procedures

Thumb carpometacarpal joint

OA in the trapeziometacarpal joint is particularly common in perimenopausal women. Patients often complain of thumb weakness because of pain. Examination may reveal a positive grind test, which is axial compression of the joint causing pain from the denuded articular surfaces rubbing against each other. The initial treatment may consist of splinting or steroid injection into the joint. Early disease may require tendon reconstruction of the volar beak ligament using a strip of flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon. A metacarpal osteotomy that redistributes force to the dorsal portion of the joint may stabilize the joint and decrease abnormal wear patterns. However, most patients presenting to surgeons already have sufficient joint destruction that requires a more complex reconstructive approach.

For degenerative changes in the thumb CMC joint, surgical treatment is based on trapeziectomy augmented by adjuvant procedures including ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI), abductor pollicis longus suspensionplasty, trapeziometacarpal joint replacement, or CMC arthrodesis (Fig 9). The LRTI procedure involves resection of the trapezium with inserting the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon through the base of the thumb metacarpal to stabilize the base of the thumb. The void created by the trapeziectomy is filled with the remaining FCR tendon. The abductor pollicis longus suspensionplasty uses the dorsal slip of the abductor pollicis longus (APL) by weaving the tendon into the ERCL. This procedure is the current preferred technique by the senior author. Data comparing outcomes amongst the various procedures are limited and inconclusive. A recent systematic review showed that no one procedure is significantly better. It appears that trapeziectomy alone has the lowest complication rate and that trapeziectomy with LRTI had the highest complication rate (10).

For heavy laborers, trapeziometacarpal fusion is a reasonable option. Arthrodesis with 30-40 degrees of abduction, 15- 20 degrees of extension, and sufficient pronation to allow tip-to-tip pinch function produces the best functional outcome. A common pitfall in treating thumb CMC disease is the failure to treat concomitant hyperextension of the MCP joint. The untreated compensatory hyperextension of the thumb MCP will stress the reconstructed CMC joint and causes failure of this procedure. Volar capsulodesis by advancing the volar plate proximally or MCP fusion are common ancillary procedures.

Interphalangeal joints

Treatment of the PIP joint in an OA hand is dependant on location. In general, the radial digits tend to be treated with arthrodesis to provide a strong post for pinch. In contrast, the ulnar digits require motion and should undergo arthroplasty. The method of arthrodesis is dependent on personal experience. Options include k-wires, screws, or tension banding. Silicone arthroplasty gives limited motion of 30-40 degrees at the PIP joints and lateral instability is common. Recent advances in pyrolytic carbon implants has led to greater motion, but complications such as dislocation of the implant can be particularly difficult to treat. When considering fusion, the PIP joint of the index finger is fused at 25 degrees of flexion, advancing by 5 degrees for each finger ulnarly.

The DIP joint is also commonly affected in OA. Enlarged osteophytes can be removed, and when the joint is destroyed, fusion is an excellent option. Arthroplasty is not indicated because the DIP joints require stability. Fusion at about 5-10 degrees of flexion is appropriate.

Summary

The hand manifestations of OA can be debilitating. The initial treatment is still medical and many patients can do well with splinting and hand therapy. Appropriate use of arthroplasty and arthrodesis for the affected joints requires careful consideration of patients' needs for the affected digits.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected muscloskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1998;41:778–799. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung KC, Kotsis SV, Kim HM, et al. Reasons Why Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Seek Surgical Treatment for Hand Deformities. The Journal of Hand Surgery. 2006;31A:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghattas L, Mascella F, Pomponio G. Hand surgery in rheumatoid arthritis: state of the art and suggestions for research. Rheumatology. 2005;44:834–245. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alderman AK, Chung KC, Demonner S, et al. The Rheumatoid Hand: A Predictable Disease With Unpredictable Surgical Practice Patterns. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2005;47:537–542. doi: 10.1002/art.10662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alderman AK, Chung KC, Kim HM, et al. Effectiveness of Rheumatoid Hand Surgery: Contrasting Perceptions of Hand Surgeons and Rheumatologists. The Journal of Hand Surgery. 2003;28A:3–11. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2003.50034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papp SR, Athwal GS, Pichora DR. The Rheumatoid Wrist. Journal of the American Acadamy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2006;14:65–77. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung KC, Kotsis SV, Kim HM. A Prospective Outcomes Study of Swanson Metacarpophalangeal Joint Arthroplasty for the Rheumatoid Hand. The Journal of Hand Surgery. 2004;29A:646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Souter W. Planning Treatment of the Rheumatoid Hand. The Hand. 1979;11:3–15. doi: 10.1016/s0072-968x(79)80002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fumagalli M, Pieracarlo SP, Atzent F. Hand Osteoarthritis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;34(6 Suppl 2):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wajon A, Ada L, Edmunds I. Surgery for the thumb (trapeziometacarpal joint) osteoarthrtitis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;4:1–61. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004631.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]