Abstract

Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSLs) catalyze the thioesterification of long-chain FAs into their acyl-CoA derivatives. Purified ACSL4 is an arachidonic acid (20:4)-preferring ACSL isoform, and ACSL4 is therefore a probable regulator of lipid mediator production in intact cells. Eicosanoids play important roles in vascular homeostasis and disease, yet the role of ACSL4 in vascular cells is largely unknown. In the present study, the ACSL4 splice variant expressed in human arterial smooth muscle cells (SMCs) was identified as variant 1. To investigate the function of ACSL4 in SMCs, ACSL4 variant 1 was overexpressed, knocked-down by small interfering RNA, or its enzymatic activity acutely inhibited in these cells. Overexpression of ACSL4 resulted in a markedly increased synthesis of arachidonoyl-CoA, increased 20:4 incorporation into phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylinositol, and triacylglycerol, and reduced cellular levels of unesterified 20:4. Accordingly, secretion of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) was blunted in ACSL4-overexpressing SMCs compared with controls. Conversely, acute pharmacological inhibition of ACSL4 activity resulted in increased release of PGE2. However, long-term downregulation of ACSL4 resulted in markedly reduced PGE2 secretion. Thus, ACSL4 modulates PGE2 release from human SMCs. ACSL4 may regulate a number of processes dependent on the release of arachidonic acid-derived lipid mediators in the arterial wall.

Keywords: fatty acid, vascular biology, eicosanoid

Arachidonic acid (20:4) is an omega-6 FA with a plethora of effects in vascular cells due to its processing by cyclooxygenases (COX-1 and COX-2), lipoxygenases, or cytochrome P450 pathways into lipid mediators with diverse biological activities, such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), prostacyclin, leukotrienes, and thromboxanes (1, 2). These lipid mediators are crucial regulators of vascular homeostasis, but also play important roles in vascular disease, including atherosclerosis. For example, studies in mouse models have demonstrated that prostacyclin exerts athero-protective effects, whereas PGE2, thromboxane A2, and leukotriene B4 promote atherosclerosis (3–6). Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) contribute to atherosclerosis through increased accumulation in the developing lesion, and later by forming a fibrous cap covering advanced lesions (7), and are believed to be an important source of 20:4-derived lipid mediators in the vascular wall. As in other cells, release of 20:4-derived lipid mediators from human arterial SMCs is dependent on liberation of 20:4 from membrane phospholipids by activation of phospholipase A2 through the action of, e.g., growth factors (8) and cytokines. Free 20:4 is then converted by COX-1/COX-2, or lipoxygenases to downstream lipid mediators, including PGE2, a principal prostaglandin species secreted from human SMCs (9, 10). However, little is known about the upstream events regulating 20:4 incorporation into phospholipids in SMCs.

Incorporation of free 20:4 into phospholipids requires thioesterification of free 20:4 by enzymes belonging to the group of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases. These enzymes produce acyl-CoAs from FAs >12 carbons in length. There are five long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (ACSL) isoforms in humans and rodents: ACSL1, ACSL3, ACSL4, ACSL5, and ACSL6 (11–13). On the basis of data generated with purified or recombinant ACSL enzymes, these isoforms have different FA preferences and different tissue expression. Recombinant ACSL4 exhibits a high preference for 20:4 and omega-3 FAs (fish oils), and lower activity with saturated, mono-, di-, and trisaturated 12–18-carbon FAs (14). In humans, ACSL4 undergoes alternative splicing, producing a shorter isoform (variant 1) and a longer isoform (variant 2) containing an additional 41-amino acid N-terminal tail (15, 16).

We have previously shown that ACSL4 is one of the ACSL isoforms expressed in human arterial SMCs (17). These cells also express ACSL1, ACSL3, and ACSL5 (17). In the present study, we therefore asked if ACSL4 modulates 20:4 bioavailability and plays a role in PGE2 production in these cells. Our results demonstrate that human arterial SMCs express ACSL4 variant 1, which allows important incorporation of 20:4 into phospholipids and, in turn, modulates PGE2 release. These observations suggest that SMC ACSL4 might play an important role in vascular biology and pathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

Normal human newborn aortic SMCs were isolated by an explant method, as previously described (18). SMCs used for experiments were maintained in DMEM 5 mM glucose with 10% FBS. Cells were infected with retrovirus for ACSL1 or ACSL4 overexpression at passage 6, and were used for experiments through passage 10. In a few experiments, immortalized primary human aortic SMCs (19) were used. Unless otherwise noted, subconfluent SMCs were quiesced for 24–48 h in DMEM 5 mM glucose plus 0.5% human plasma-derived serum before experiments. SMCs were infected with retroviral vectors for ACSL overexpression 10 different times over a period of three years with similar results. ACSL4 siRNA experiments were done in two independent infections with similar results. FAs oleic acid (18:1), palmitic acid (16:0), or arachidonic acid (20:4) were added to the cells prebound to 0.5% FA-free BSA at a BSA:FA molar ratio of <1:3. All experiments using human tissues were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington.

Phoenix amphotropic cells (Orbigen; San Diego, CA) were maintained in DMEM 25 mM glucose, 10% FBS, nonessential amino acids, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. After transfection, 1 μg/ml puromycin was added in order to select for successfully transfected cells.

Analysis of endogenous ACSL isoforms and ACSL4 splice variants in SMCs

Human ACSL4 has two splice variants, variant 1 (NM_004458) and the longer variant 2 (NM_022977). To determine which ACSL4 variant is expressed in SMCs, real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) primers were designed (Applied Biosystems Primer Express 2.0 software), and ordered from Operon (Huntsville, AL). Primers were used to detect ACSL4 variant 2 or both variants 1 and 2 (Table 1). Total RNA was extracted from SMCs, using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA), and used for semi-quantitative or real-time qPCR, as described below. Real-time PCR was also used to measure mRNA levels of other ACSL isoforms and FA transport protein (FATP) isoforms, at least some of which have acyl-CoA synthetase activity (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Primers for real-time qPCR and semi-quantitative RT-PCR

| Primer | Primer Sequence | Amplicon Length |

|---|---|---|

| Real-time qPCR | ||

| ACSL1-F | 5′-AACAGACGGAAGCCCAAGC-3′ | 102 bp |

| ACSL1-R | 5′-TCGGTGAGTGACCATTGCTC-3′ | |

| ACSL3-F | 5′-CCCCTGAAACTGGTCTGGTG-3′ | 73 bp |

| ACSL3-R | 5′-TCCGCCTGGTAATGTGTTTTAA-3′ | |

| ACSL4-F variant 2 | 5′-GGCGTACTTTATTGTCGGCTTC-3′ | 75 bp |

| NM_022977 | ||

| ACSL4-R variant 2 | 5′-TACAGCCAAGGCAGTTCAATCTTAG-3′ | |

| ACSL4-F | 5′-GCTTCCTATCTGATTACCAGTGTTGA-3′ | 96 bp |

| ACSL4-R | 5′-GTCCACATAAATGATATGTTTAACACAACT-3′ | |

| ACSL5-F | 5′-CCCCATGTCCACTTCAGTCAT-3′ | 84 bp |

| ACSL5-R | 5′-GTGCATTCTGTTTGACCATAAGCT-3′ | |

| FATP1-F | 5′-CTGCCCTTAAATGAGGCAGTCT-3′ | 64 bp |

| FATP1-R | 5′-AACAGCTTCAGAGGGCGAAG -3′ | |

| FATP3-F | 5′-TACCTGCCCCTCACAACTGC-3′ | 70 bp |

| FATP3-R | 5′-GTGGAAGTTCTCAGATTCGAAGG-3′ | |

| FATP4-F | 5′-TTCTGTGAAAGTCTCATGTCCAAGT-3′ | 69 bp |

| FATP4-R | 5′-TCTCAGCCTGGGAACCAGAG-3′ | |

| 18S-F | 5′-CATTAAATCAGTTATGGTTCCTTTGG-3′ | 88 bp |

| 18S-R | 5′-CCCGTCGGCATGTATTAGCT-3′ | |

| RT-PCR | ||

| ACSL1-F | 5′-TGCAGCACTCACCACCTTC-3′ | 582 bp |

| ACSL1-R | 5′-TAGGCATCCATGACAACTA-3′ | |

| ACSL4-F | 5′-CCGACCTAAGGGAGTGATGA-3′ | 169 bp |

| ACSL4-R | 5′-CCTGCAGCCATAGGTAAAGC-3′ | |

| β-actin-F | 5′-ATCTGGCACCACACCTTCTACAATGAGCTGCG-3′ | 852 bp |

| β-actin-R | 5′-CGTCATACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCTGC-3′ | |

qPCR, quantitative PCR.

Creation of retroviral vectors for ACSL4 and ACSL1 overexpression

Human cDNA ACSL4 variant 1 (NM_004458) and human ACSL1 variant 2 (NM_001995.2) clones were obtained in plasmid cytomegalovirus expression vectors from OriGene (Rockville, MD). The retroviral pBM-IRES-PURO (pBM) vector, which contains a puromycin resistance element (20), was used to generate vectors for stable overexpression of ACSL4 and ACSL1. Briefly, the plasmid cytomegalovirus vectors were used to transform XL-1 Blue Supercompetent cells (Stratagene; Cedar Creek, TX). The ACSL sequences were amplified using cloning primers with a Kozak sequence added to the beginning of the 5′ primer (Invitrogen). The PCR products were gel purified and ligated into the pGEM-T Easy Vector, a TOPO vector (Promega; Madison, WI), and the ACSL sequences were then excised and ligated into the dephosphorylated pBM vector. A pBM-eGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) plasmid was used as a positive control. All vectors were sequenced to verify correct directionality by using an ABI 3730XL high-throughput capillary DNA analyzer.

Phoenix amphotropic cells (70–80% confluent cultures) were transfected with the empty pBM vector, pBM-eGFP, pBM-ACSL4, or pBM-ACSL1 plasmids by CaCl2 transfection, according to Orbigen's instructions. The next day, the cells were passaged into media containing 1 μg/ml puromycin for positive selection, and then maintained in media containing puromycin until virus collection at ∼90% confluency. The retrovirus-containing media, collected in fresh medium during a 24 h period, were removed from the Phoenix cells and filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter, and 4 mg/ml polybrene (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) was added. Retrovirus was incubated with the SMCs for 16–18 h. The SMCs were then treated with puromycin at 5 μg/ml for 36–48 h until all nonvirus-treated control SMCs were dead.

ACSL4 siRNA experiments

Immortalized human primary aortic SMCs were transduced for stable expression of ACSL4 siRNAs, using HuSHTM 29 mer constructs (OriGene Technologies, Inc.; Rockville, MD). Four different ACSL4 siRNA constructs in the pRS plasmid, negative control pRS plasmid, and a scrambled negative control siRNA in the pRS plasmid (OriGene) were used for generation of SMCs stably expressing these constructs following transfection of Phoenix amphotropic cells, and subsequent transduction of SMCs, as described above. Initial experiments revealed that the ACSL4 siRNA construct TI359914 (CGCTATCTCCTCAGACACACCGATTCATG) resulted in the most significant (60–70%) downregulation of ACSL4, and this construct, together with the two controls, was used for subsequent experiments. Another construct, TI359913 (GGCTCATGTGCTAGAACTGACAGCAGAGA), resulted in a less-marked (∼30%) reduction of ACSL4, and was used as an additional control in some experiments. Following SMC infection with these constructs, transduced cells were selected by puromycin incubation, as described above.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA (250 ng) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using random hexamers and 0.2 U/ml Omniscript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 60 min. The cDNA template was then amplified with PCR using a GeneAmp PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with a primer concentration of 400 nM. ACSL primers were designed using Primer3 (21). β-actin primers were from Clontech Labs, Inc. (Mountain View, CA). The PCR products were separated by gel electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide.

Real-time PCR

RNA was treated with RNase Free DNase I (Stratagene). Real-time qPCR was performed on an Mx4000 Multiplex QPCR System (Stratagene). RNA samples (20 ng) were loaded in triplicate and run in a 10 μl reaction using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix. Each reaction contained 5 μl 2× Master Mix, 400 nM of each primer, 0.5 units of StrataScript RT, and 0.5 units of RNase Block and was run with PCR cycling conditions of 48°C for 30 min, 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Dissociation curves were run to confirm specificity of all PCR amplicons. For standard curves, PCR amplicons were used at 1:4 serial dilutions. Results were then converted to copy number and normalized to total RNA levels, or were normalized to 18S. Total RNA and PCR amplicons were quantitated on an Mx4000 Multiplex QPCR System using the RiboGreen RNA Quantitation Kit (Molecular Probes; Eugene, OR) and standards from the manufacturer.

Detection of ACSL4 and ACSL1 by Western blot

SMCs in 10-cm dishes were harvested in Western lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na2SO4, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1% Triton-X, 5 mM benzamidine, 10 mg/ml aprotinin, 20 mg/ml leupeptin, and 5 mg/ml pepstatin). Protein concentrations were determined using a modified BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific; Rockford, IL). Cell lysates (60 μg) were then resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and electro-transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes overnight. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in TBS/0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. A polyclonal ACSL1 antibody (Aviva Systems Biology; San Diego, CA) was used at a dilution of 1:500 in 5% milk in PBS. A polyclonal anti-rat ACSL4 antibody was generously provided by Dr. Rosalind Coleman (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC), and used at a 1:10,000 dilution, as described previously (17). After primary antibody incubation, membranes were incubated with secondary antibody (anti-rabbit-HRP at a 1:5,000 dilution) and developed with chemoluminescent reagent. To verify equal loading, membranes were stripped and reprobed with a monoclonal β-actin antibody (Sigma) at a 1:15,000 dilution, followed by anti-mouse-HRP at a 1:15,000 dilution.

Analysis of ACSL activity

ACSL activity was determined as previously described (17). Briefly, cell lysates (50–200 μg) were incubated for 20 min at 37°C in a reaction mixture containing 175 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 8 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 10 mM ATP, 2 mM CoA with 50 mM [9,10(n)-3H]18:1 (1 μCi), [5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H]20:4, or [9,10(n)-3H]16:0 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences; Piscataway, NJ). After extraction, the radioactivity of the lower aqueous phase was used to calculate ACSL enzymatic activity. The results were corrected for blanks (samples without cell lysates added and samples analyzed in the absence of CoA or ATP) and for protein content. All reactions were confirmed to occur within the linear range.

Analysis of long-chain acyl-CoA species

Long-chain fatty acyl-CoAs were quantified by LC-ESI-MS/MS, as described by Haynes et al. (22). Briefly, cells were homogenized in 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH 4.9), and fatty acyl-CoAs were extracted (23). For LC/ESI/tandem MS experiments, an Agilent 6410 triple quadruple MS system equipped with an Agilent 1200 LC system and an ESI source was utilized. The neutral loss of m/z 507 is the most-intense product ion for each compound. Acyl-CoA species were detected by their characteristic LC retention time in the multiple reaction monitoring mode following ESI. A known amount of C17:0 acyl-CoA was added into the biological samples to quantify C16:0 (palmitoyl-CoA), C18:0 (stearoyl-CoA), C18:1 (oleoyl-CoA), 20:4 (arachidonoyl-CoA), and C22:6 (docosahexaenoyl-CoA) by comparing the relative peak areas in the reconstructed ion chromatogram in the multiple reaction monitoring mode.

Determination of beta-oxidation by acid-soluble metabolite production, and triacylglycerol mass

The production of acid-soluble metabolites was used as an index of the β-oxidation of FAs. SMCs were incubated in DMEM + 0.5% FA-free BSA with 50 μM carnitine and 0.1 μCi [1-14C]18:1 (50–62 mCi/mmol), 0.1 μCi [1-14C]16:0 (50–62 mCi/mmol), or 0.5 μCi [5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H]20:4 (150–230 Ci/mmol, all from GE Healthcare Life Sciences) per well in 6-well plates. After 24 h, 800 μl of the medium was harvested on ice, and 200 μl of ice-cold 70% perchloric acid was added in order to precipitate BSA:FA complexes. The samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 g, and the radioactivity of the supernatant was determined by liquid scintillation (24). The cells were then harvested in 1 M NaCl for protein analysis.

For analysis of triacylglycerol (TAG) mass in SMCs, cells in 10-cm dishes were treated with DMEM, 0.5% FA-free BSA, 50 μM carnitine, and 10–70 μM 18:1, 16:0, or 20:4 for 24–48 h. Lipids were extracted using a modified Bligh and Dyer method (25). A colorimetric TAG kit (Sigma) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis of FA incorporation into neutral lipids and phospholipids

Cells were plated and treated as described for the acid-soluble metabolite assay. After 5–10 min or 24 h, the cells were placed on ice, washed with PBS, and then harvested with 0.5 ml 1 M NaCl per well. For analysis of FA incorporation into neutral lipids, cell lysates from two wells on a 6-well plate were pooled. Lipids were extracted by using a modified Bligh and Dyer method (25), and were loaded, together with mono-, di-, and triglyceride standards (NuChek Prep), onto unmodified Silica Gel G TLC plates (Sigma) preheated at 60°C for 15 min. The lipids were separated for 45–60 min, using a mobile phase of hexane-diethyl ether-glacial acetic acid (105:45:3). Lipid spots were visualized by iodine vapor. An Amersham Biosciences Storm 860 PhosphorImager was then used to detect and quantify the radioactivity in each lipid spot, or the radioactivity was detected by liquid scintillation following scraping of the spots.

For analysis of [3H]20:4 incorporation into phospholipids, SMCs were treated with 0.1 μCi/ml [3H]20:4 (0.5 nM) for 5–15 min and then harvested with 1 M NaCl. Lipids were extracted as described above. Incorporation of [3H]20:4 into the phospholipid pool was first examined by TLC, as described for neutral lipid analysis. To analyze incorporation into specific phospholipids by HPLC, samples were resuspended in 2 ml CH3Cl-acetic acid (100:1) and were then run through Sep-pak columns (Sep-pak vac 3 cc, 500 mg, silica cartridges; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). The phospholipids were eluted by step-wise addition of 2 ml CH3Cl-acetic acid (100:1) two times, 2 ml methanol-CH3Cl (2:1) three times, and 2 ml methanol-CH3Cl-H2O (2:1:0.8) three times. The eluted phospholipid solution was condensed and resuspended in 50 μl HPLC-grade methanol and run through reverse-phase HPLC (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments; Columbia, MD). Phospholipids in each 1 ml fraction were analyzed by determining the incorporation of [3H]20:4 by liquid scintillation, as described previously (26). The phospholipids were identified by comparison to elution times of phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and phosphatidylcholine (PC) standards (Avanti Polar Lipids; Alabaster, AL), detected by ultraviolet monitoring at 206 nm.

To determine the endogenous relative distribution of FAs in PE and PC, human SMCs, maintained in 10% FBS, were harvested, and lipids were extracted by the Bligh and Dyer method (25) and then processed as described by Hamilton and Comai (27). In short, the extracted lipids were dried under nitrogen, and then resolubilized in CH3Cl-acetic acid at a ratio of 100:1 and separated on Sep-pak columns (Waters) equilibrated with hexane-methyltertiarybutylether (96:4), as described above. The samples were eluted in three fractions. Fraction 1, consisting primarily of neutral lipids and free FAs (27), was eluted in 2 + 2 + 12 ml CH3Cl-acetic acid (100:1); fraction 2, enriched in PE (27), was eluted by 5 ml methanol-CH3Cl (2:1); and fraction 3, enriched in PC (27), was eluted in 5 ml methanol-CH3Cl-H2O (2:1:0.8). Fractions 2 and 3 were dried separately under nitrogen and used for analysis of FA composition. FAs were methylated under acidic conditions (25 μl of H2SO4 into 975 μl of methanol) for 60 min at 80°C, followed by a hexane-H2O extraction (200:1,500). The hexane layer was collected after freeze-separation and loaded onto a GC-mass spectrometer (Agilent 6890-5973; Agilent Technologies, Foster City, CA). The GC-MS spectra were compared with those of known standards.

Analysis of PGE2 release

DMEM containing 0.5% FA-free BSA and 50 μM carnitine in the absence or presence of 10 μM 20:4, 10 ng/ml human recombinant interleukin-1β (IL-1β), 10 μM rosiglitazone (Alexis Biochemical; San Diego, CA), 10 μM triacsin C (Biomol; Plymouth Meeting, PA) or vehicle (DMSO) were added to SMCs. PGE2 levels were measured with an EIA kit (Cayman Chemical; Ann Arbor, MI), and were normalized to cellular protein levels.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student's t-test when comparing two groups. One- or two-way ANOVA was used to compare more than two parameters with Bonferroni or Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison tests. Experiments were performed at least three times in independently generated SMC samples.

RESULTS

Human SMCs express ACSL4 variant 1

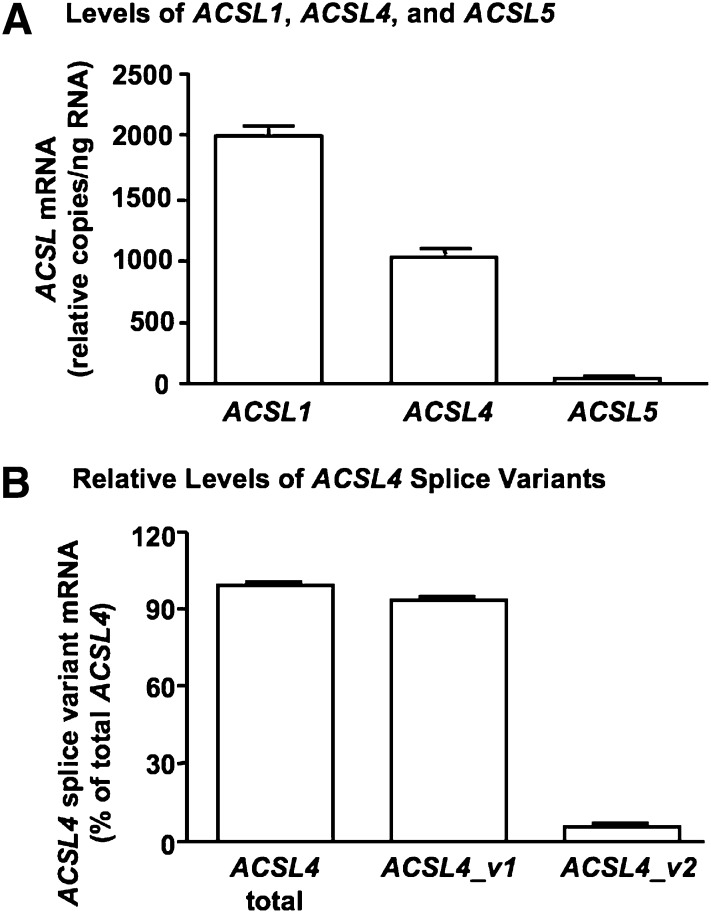

Human SMCs expressed ACSL4, consistent with our previous findings (17). The relative levels of ACSL4 mRNA were lower than those of ACSL1, but higher than those of ACSL5 (Fig. 1A). Of the two human ACSL4 splice variants, the longer variant 2 is proposed to have an N-terminal transmembrane domain and is expressed in the brain (15). The ACSL4 splice variant expressed in SMCs has not previously been identified. By using primers specific for the longer ACSL4_v2 and primers detecting both ACSL4_v1 and ACSL4_v2 (Table 1), the shorter ACSL4_v1 was found to be the primary ACSL4 splice variant expressed in human SMCs (Fig. 1B). ACSL4_v2 mRNA accounted for only 5.9 ± 0.7% of total ACSL4 mRNA levels in these cells.

Fig. 1.

Human smooth muscle cells (SMCs) express ACSL4-v1 mRNA. ACSL1, ACSL4, and ACSL5 mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR in human aortic SMCs (A). The results were normalized to total RNA levels, and are expressed as mean copy number/ng RNA ± SEM (n = 3 from three independent experiments performed at three different SMC passages). ACSL4_v2-specific primers were designed and used, together with primers that detect both ACSL4 splice variants, to evaluate relative mRNA levels of ACSL4_v1 and ACSL4_v2 (B). The results are expressed as mean ± SEM of triplicate analyses of SMCs isolated from two different donors.

Arachidonic acid is a preferred substrate for ACSL4 variant 1 in intact human SMCs

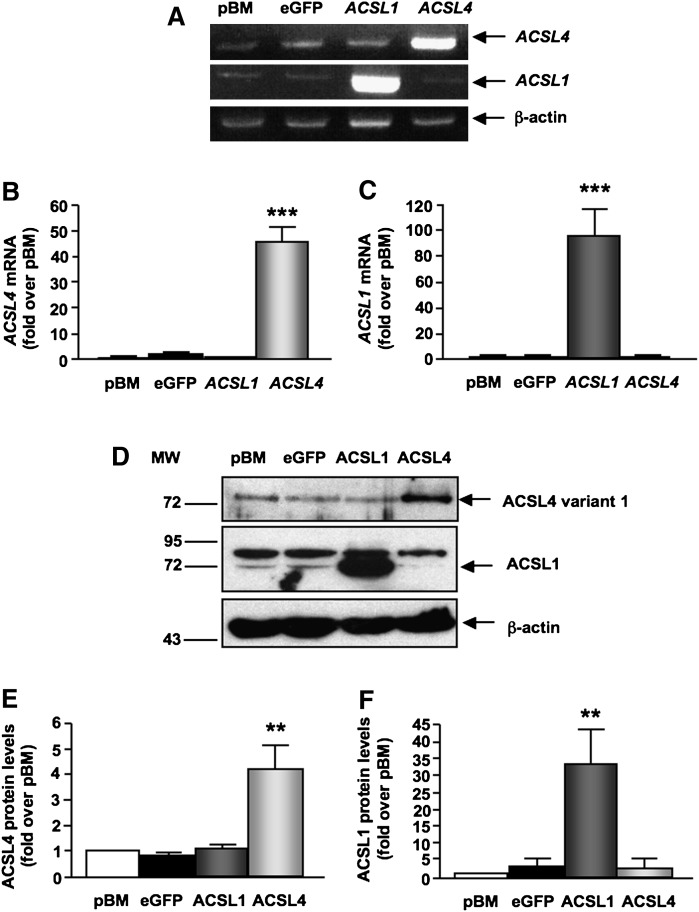

SMCs stably overexpressing ACSL4 variant 1 demonstrated marked increases in ACSL4 mRNA levels (Fig. 2A, B) and ACSL4 protein (Fig. 2D, E). ACSL4 protein levels were increased ∼4-fold in SMCs overexpressing ACSL4 compared with SMCs transduced with the empty pBM vector or eGFP (Fig. 2E). The overexpressed ACSL4 variant 1 had the same apparent molecular weight as endogenous ACSL4 (Fig. 2D), confirming that the ACSL4 variant expressed in these cells is ACSL4 variant 1.

Fig. 2.

Increased expression of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4 (ACSL4) variant 1 and ACSL1 in SMCs stably overexpressing ACSL4 or ACSL1. SMCs were stably infected with the retroviral empty vector (pBM) or vectors containing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP), human ACSL4, or human ACSL1. (A) RT-PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels and visualized via ethidium bromide staining. ACSL4 mRNA was determined at an annealing temperature of 62°C and 30 cycles, ACSL1 mRNA levels were evaluated by RT-PCR at an annealing temperature of 60°C and 32 cycles, and β-actin mRNA levels were determined at an annealing temperature of 62°C and 25 cycles. Results were verified for ACSL4 (B) and ACSL1 (C) gene expression by real-time qPCR (n = 4). (D–F) Total cell lysates (60 μg/lane) were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE. Blots were probed with anti-ACSL4, anti-ACSL1, or anti-β-actin antibodies. Band intensities were measured with the ImageJ program in arbitrary units and are presented as fold over pBM-transduced SMCs. (D) Representative blot. Results combined from an n = 3 for ACSL4 protein expression (E) and ACSL1 protein expression (F). The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with SMCs transduced with the empty pBM vector by one-way ANOVA followed by Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison test.

ACSL1, an abundant SMC ACSL isoform with a lower relative preference for 20:4, compared with that of ACSL4, was overexpressed as a control. As expected, overexpression of ACSL1 resulted in increased ACSL1 mRNA (Fig. 2A, C), as well as increased ACSL1 protein levels (Fig. 2D, F). Importantly, overexpression of ACSL4 did not alter expression levels of ACSL1 or vice versa (Fig. 2). Furthermore, ACSL4 overexpression did not affect levels of ACSL3, ACSL5, SLC27A1 (FATP1), SLC27A3 (FATP3), or SLC27A4 (FATP4) mRNA (data not shown).

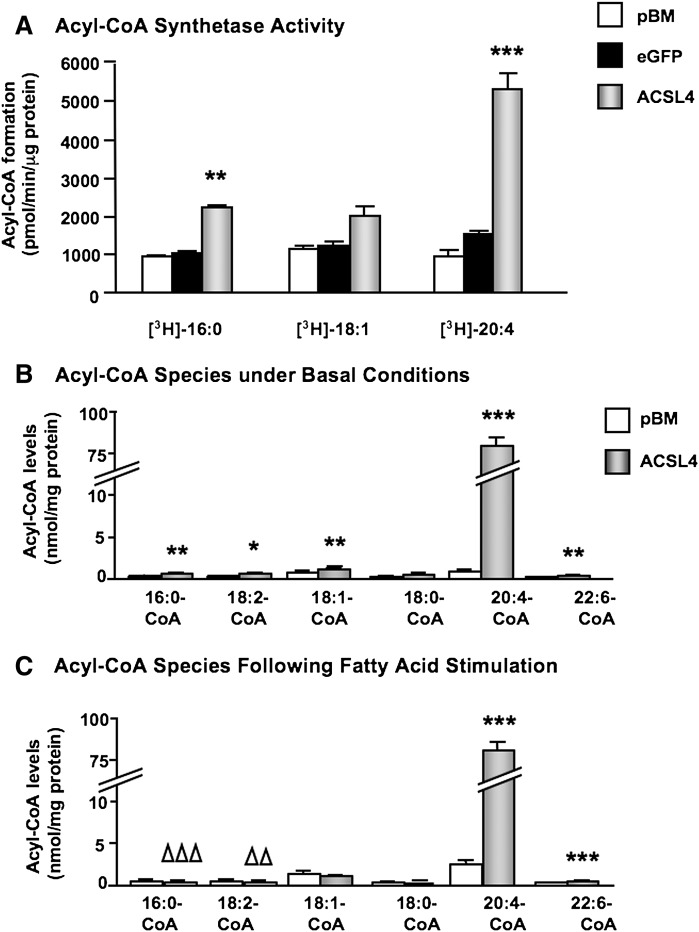

To investigate acyl-CoA synthetase activity in ACSL4-overexpressing SMCs, cell lysates were first used for in vitro ACSL activity assays. Cell lysates from SMCs overexpressing ACSL4 demonstrated a significantly elevated palmitoyl-CoA synthetase activity, and a more marked arachidonoyl-CoA synthetase activity, compared with control lysates (Fig. 3A). Oleoyl-CoA synthesis was not significantly elevated by ACSL4 overexpression in these cell lysate experiments. Next, levels of the six most-abundant acyl-CoA species were determined by LC-ESI-MS/MS in intact SMCs overexpressing ACSL4 and controls. ACSL4 overexpression resulted in markedly increased arachidonoyl-CoA levels under basal conditions in the presence of 1% human plasma-derived serum (Fig. 3B). Smaller, but significant, increases were observed in palmitoyl-CoA, linoleoyl-CoA, oleoyl-CoA, and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)-CoA levels (Fig. 3B). When SMCs were challenged with a mixture of 70 μM 16:0, 70 μM 18:1, and 10 μM 20:4, the same marked increase in arachidonoyl-CoA levels was evident in ACSL4-overexpressing SMCs, whereas the small increases in all other acyl-CoA species except for DHA-CoA were lost, or even reduced (Fig. 3C), supporting the notion that 20:4 is a preferred substrate for ACSL4 in human SMCs.

Fig. 3.

Overexpression of ACSL4 results in marked increase in arachidonoyl-CoA synthesis. (A) Lysates from SMCs transduced with the empty pBM vector, eGFP, or ACSL4, were incubated with 1 μCi [3H]16:0, [3H]18:1, or [3H]20:4 in the presence of ATP and CoA for 20 min at 37°C. Formed [3H]palmitoyl-CoA, [3H]oleoyl-CoA, and [3H]arachidonoyl-CoA were separated via a single phase extraction, and the radioactivity was determined via scintillation counter. The results are expressed as means ± SEM (n ≥ 3). (B) Acyl-CoA levels were analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS in SMCs under basal conditions (0.5% human plasma-derived serum), and (C) in SMCs incubated for 4 h in the presence of 70 μM 16:0, 70 μM 18:1, plus 10 μM 20:4 in the presence of 0.5% FA-free BSA (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 denote significant increases in ACSL4-overexpressing cells, whereas ΔΔP < 0.01 and ΔΔΔP < 0.01 denote significant decreases in ACSL4-overexpressing cells compared with SMCs transduced with the empty pBM vector by one-way ANOVA followed by Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison test.

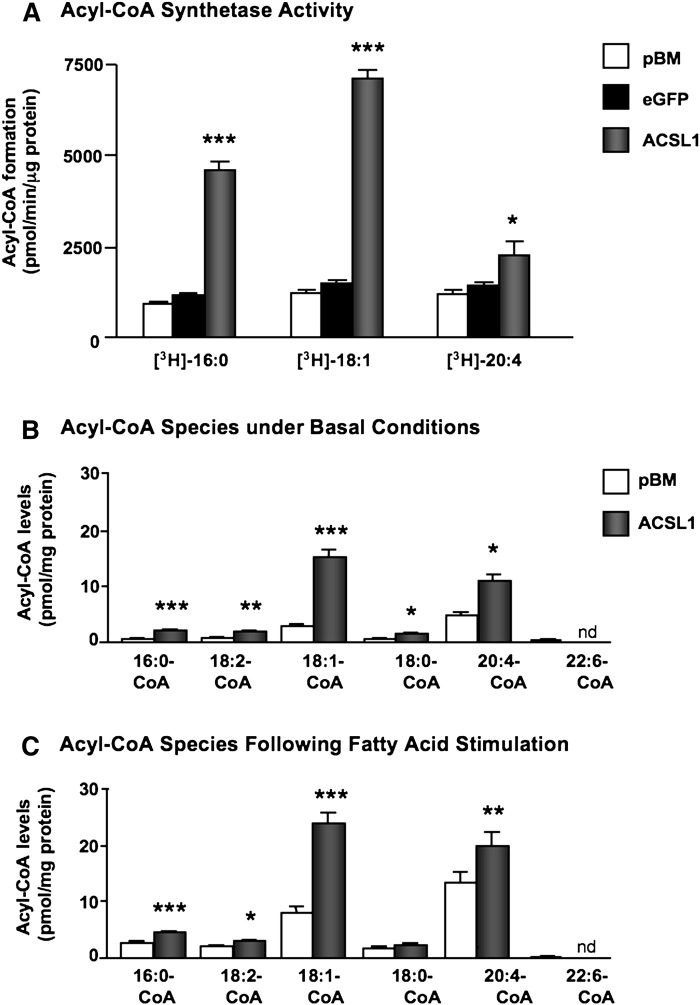

On the other hand, overexpression of ACSL1 resulted in large increases in oleoyl-CoA synthesis and palmitoyl-CoA synthesis in SMC lysates (Fig. 4A). The increase in arachidonoyl-CoA synthesis was much lower than that achieved by ACSL4 overexpression despite the higher levels of ACSL1 overexpression compared with ACSL4 (compare Fig. 2E, F). Consistently, ACSL1 overexpression resulted in increased levels of palmitoyl-CoA, linoleoyl-CoA, oleoyl-CoA, stearoyl-CoA, and arachidonoyl-CoA in intact SMCs under basal conditions, and a similar pattern was seen in FA-stimulated cells (Fig. 4B, C). Levels of arachidonoyl-CoA were much lower in ACSL1-overexpressing SMCs than in ACSL4-overexpressing SMCs (compare Figs. 3B, C and 4B, C).

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of ACSL1 results in a less marked increase in arachidonoyl-CoA synthesis. (A) Lysates from SMCs transduced with the empty pBM vector, eGFP, or ACSL1, were incubated with 1 μCi [3H]16:0, [3H]18:1, or [3H]20:4 in the presence of ATP and CoA for 20 min at 37°C. Formed [3H]palmitoyl-CoA, [3H]oleoyl-CoA, and [3H]arachidonoyl-CoA were separated via a single phase extraction, and the radioactivity was determined via scintillation counter. The results are expressed as means ± SEM (n ≥ 3). (B, C) Acyl-CoA levels were analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS as described in Fig. 3 (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with SMCs transduced with the empty pBM vector by one-way ANOVA followed by Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison test. nd, not detected.

Together, these results show that ACSL4 variant 1 has a strong preference for arachidonic acid compared with that of ACSL1, and markedly stimulates arachidonoyl-CoA synthesis in SMCs.

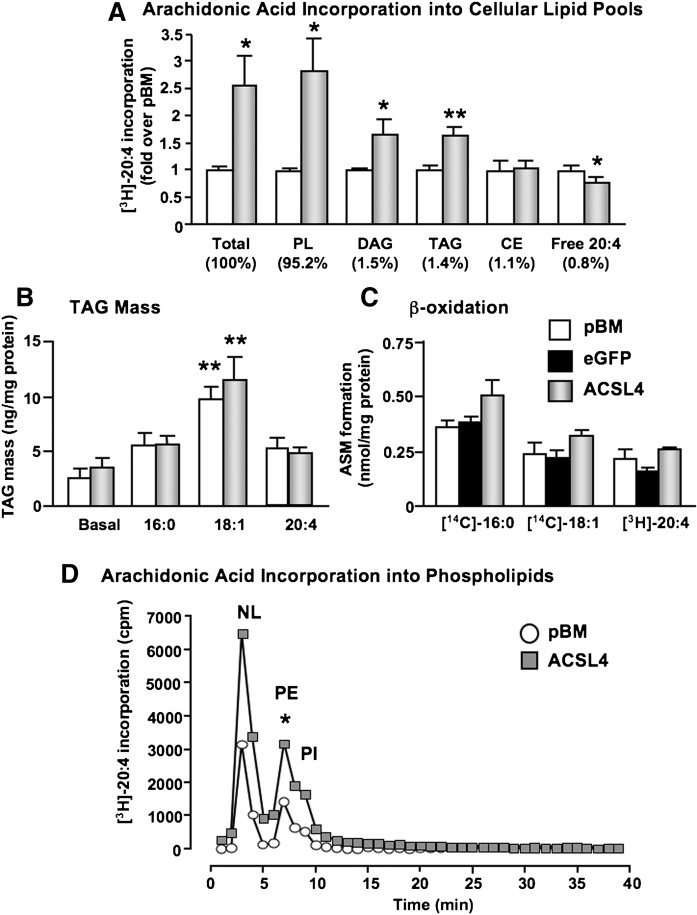

Overexpression of ACSL4 results in increased incorporation of arachidonic acid into phospholipids and TAG

To determine the effects of ACSL4 overexpression on 20:4 incorporation into different cellular lipid pools, SMCs were treated with [3H]20:4 for 5 min–24 h. Lipids were extracted and then separated by TLC. Five minutes after addition of [3H]20:4 to SMCs, more than 95% of the total cellular [3H]20:4 was found in the phospholipid pool, with 1–2% in diacylglycerol (DAG), TAG, and cholesteryl esters, respectively (Fig. 5A). Less than 1% of the added [3H]20:4 was found as cellular free unesterified 20:4. Total cellular [3H]20:4 levels were significantly elevated in ACSL4-overexpressing cells, as was incorporation into phospholipids, DAG, and TAG (Fig. 5A). Importantly, free [3H]20:4 levels were significantly reduced in ACSL4-overexpressing SMCs (Fig. 5A). These effects were transient, and were no longer observed 24 h after stimulation of the cells with [3H]20:4 (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

ACSL4 regulates rapid 20:4 incorporation into PE, Pl, and diacylglycerol/triacylglycerol (DAG/TAG) in SMCs. (A) SMCs were treated with 1 μCi [3H]20:4 for 5 min. Total cellular lipids were then extracted and separated via TLC. Free 20:4, as well as 20:4 incorporation into cholesteryl ester (CE), TAG, DAG, and phospholipids (PL) were quantified by PhosphorImager. Lipid spots were measured in arbitrary units using the ImageQuant program, and values were compared with total protein levels of cell lysates. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 4 independent experiments). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by Student's t-test. (B) SMCs were treated with or without FAs for 48 h. Lipids were then extracted from cell lysates, and TAG levels were analyzed through a colorimetric assay (Sigma). Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA comparing FA-stimulated pBM and ACSL4 cells to the respective basal levels. (C) To evaluate β-oxidation, SMCs were labeled with 0.1 μCi [14C]18:1, [14C]16:0, or 0.5 μCi [3H]20:4 for 24 h. Conditioned media were collected, and acidified with 70% perchloric acid. The amounts of radiolabeled acid-soluble metabolites were then measured by scintillation counter. The results are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3) normalized to the specific activity of the radioactive FA. (D) SMCs were treated with 1 μCi [3H]20:4 for 10 min. Lipids were extracted and run through Sep-pak columns to further extract phospholipids. The extracts were then run through an HPLC column. Lipid peaks (NL, neutral lipids; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PI, phosphatidylinositol) were determined by analyzing known standards. Results from a representative experiment are shown. *P < 0.05 comparing the PE/PI peak in ACSL4-overexpressing SMCs with controls in three different experiments by Student's t-test.

We next investigated whether the increased 20:4 incorpor.2.1'ation into TAG would be reflected by increased TAG accumulation in the cells. However, TAG mass was not different in SMCs overexpressing ACSL4 versus control SMCs (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, whereas 70 μM 18:1 significantly stimulated TAG accumulation in both control SMCs and in SMCs overexpressing ACSL4, neither 70 μM 16:0 nor 10 μM 20:4 had a significant stimulatory effect on TAG accumulation after a 48 h stimulation period (Fig. 5B). ACSL4 overexpression also did not enhance TAG accumulation in SMCs stimulated with 70 μM 20:4 (data not shown). Moreover, overexpression of ACSL4 did not increase acid-soluble metabolite production (a measure of β-oxidation) from any of the FAs investigated (Fig. 5C).

Thus, ACSL4 overexpression increases 20:4 incorporation primarily into phospholipids in SMCs, but has no detectable effects on TAG mass or β-oxidation.

ACSL4 overexpression results in rapidly increased 20:4 incorporation into PE and PI

To identify the phospholipids affected by the increased 20:4 incorporation in ACSL4-overexpressing SMCs, the most common phospholipids were separated and analyzed by HPLC. As shown in Fig. 5D, [3H]20:4 was incorporated into PE and PI 5–15 min after 20:4 stimulation, whereas incorporation into PC and PS was undetectable in most experiments. SMCs overexpressing ACSL4 exhibited an increased [3H]20:4 incorporation into both PE and PI, as compared with control SMCs transduced with the empty pBM vector (Fig. 5D).

To investigate the distribution of endogenous 20:4 in PE and PC pools, the relative FA composition of PE- and PC-enriched lipid fractions was analyzed by GC-MS. As shown in Table 2, the relative contribution of 20:4 was significantly higher in the PE-enriched fraction, as compared with the PC-enriched fraction. Furthermore, the relative level of 16:0 was higher and the relative level of 18:0 was lower in the PC-enriched fraction, as compared with the PE-enriched fraction (Table 2). Thus, although endogenous 20:4 is present in both PE and PC, it contributes a significantly larger fraction of the FAs present in PE, which may be consistent with our HPLC results demonstrating exogenous 20:4 incorporation mainly into PE.

TABLE 2.

Phospholipid FA composition

| Phospholipid fraction | 16:0 | 18:2 | 18:1 | 18:0 | 20:4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | |||||

| Fraction 2 (PE) | 22.5 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 13.4 ± 0.6 | 52.8 ± 1.4 | 10.2 ± 1.0 |

| Fraction 3 (PC) | 50.3 ± 5.1** | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 23.1 ± 7.8 | 24.1 ± 3.2** | 2.0 ± 0.3** |

PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM % FA out of total FA in each fraction. Differences in the relative contribution of each FA between fraction 2 and fraction 3 were analyzed by Student's t-test (n = 3; **P < 0.01).

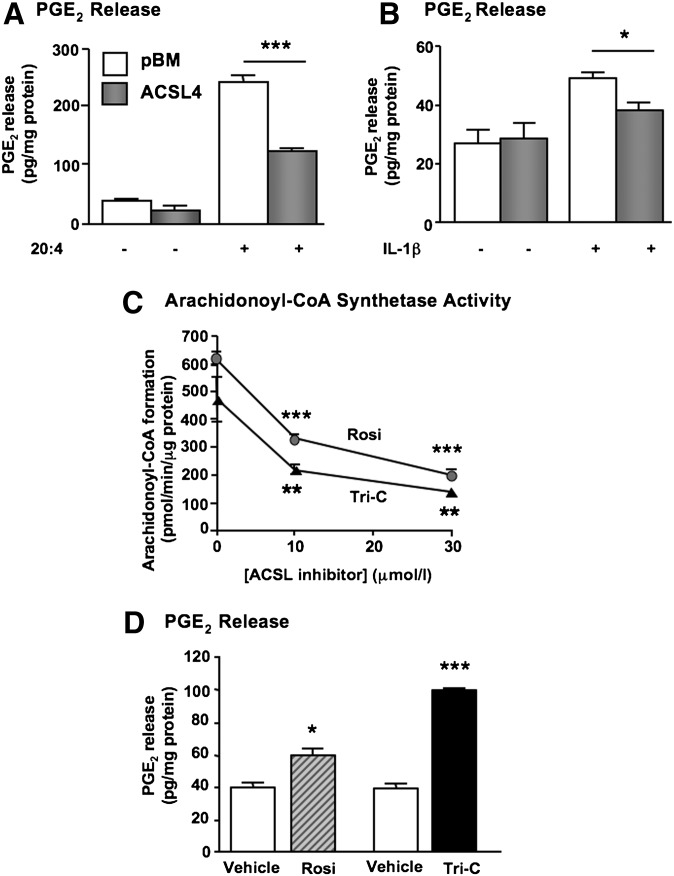

Overexpression of ACSL4 blunts 20:4- and IL-1beta-induced PGE2 release, whereas acute inhibition of ACSL4 activity promotes PGE2 release in SMCs

The phospholipid pool of 20:4 is an important contributor to prostaglandin synthesis, following hydrolysis of, e.g., PE and PI, and liberation of free 20:4 by phospholipase A2. Because human SMCs secrete significant amounts of PGE2 (10), we next investigated whether ACSL4 overexpression affects the amount of PGE2 released from SMCs. PGE2 secretion was not significantly affected by ACSL4 overexpression under basal serum-free conditions or in the presence of 10% FBS (Fig. 6A and data not shown). However, when the SMCs were challenged by 10 μM 20:4, a significant reduction in 20:4-induced PGE2 release was observed in ACSL4-overexpressing SMCs (Fig. 6A). We next investigated the effect of IL-1β, a known activator of cytosolic phospholipase A2 and PGE2 synthesis in SMCs (28), in SMCs overexpressing ACSL4 and controls. Consistent with the results in 20:4-stimulated SMCs, ACSL4 overexpression blunted IL-1β-induced PGE2 secretion (Fig. 6B). The effects of ACSL4 on PGE2 secretion were not due to changes in COX-2 expression, inasmuch as overexpression of ACSL4 did not affect basal or IL-1β-stimulated COX-2 mRNA levels (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

ACSL4 regulates prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) release from human SMCs. (A) SMCs overexpressing ACSL4 and control SMCs transduced with the empty pBM vector were incubated in the absence or presence of 10 μM 20:4 in the presence of 0.5% FA-free BSA for 15 min. PGE2 levels in the conditioned media were analyzed by an EIA kit. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM from a representative experiment performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison test. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (B) Immortalized SMCs were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 ng/ml interleukin-1β (IL-1β) for 4 h, and PGE2 levels in the conditioned media were analyzed by EIA. *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA followed by Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison test. (C) Arachidonoyl-CoA synthesis was analyzed as described in Fig. 3A in SMC lysates in the absence or presence of DMSO vehicle or the indicated concentrations of triacsin C or rosiglitazone. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with vehicle-treated controls by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison test. (D) SMCs were incubated in fresh media in the presence of 10 μM rosiglitazone (Rosi), 10 μM triacsin C (Tri-C), or vehicle (DMSO) for 2 h. PGE2 levels in the conditioned media were analyzed by an EIA kit. Results were normalized to protein and expressed as mean ± SEM from representative experiments performed in triplicate. Similar results were obtained in three to four independent experiments and in SMCs stimulated with 10 µMΜ 20:4. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 compared with matched vehicle controls by Student's t-test.

Next, to investigate the role of endogenous ACSL4 enzymatic activity in PGE2 release from SMCs, we took advantage of two pharmacological ACSL4 inhibitors. ACSL4 activity is directly inhibited by triacsin C and thiazolidinediones such as rosiglitazone (29). Triacsin C inhibits the activity of several ACSL isoforms, including ACSL4, whereas rosiglitazone is selective for ACSL4 at concentrations ≤10 μM (30). Accordingly, both triacsin C and rosiglitazone inhibited arachidonoyl-CoA synthetase activity in SMC lysates at 10 and 30 μM (Fig. 6C). Short incubations (2 h) with either rosiglitazone or triacsin C resulted in increased PGE2 release from SMCs, both under basal conditions (Fig. 6D) and in SMCs stimulated with 10 μM 20:4. (In a representative experiment, 20:4 stimulation alone resulted in levels of PGE2 in the conditioned media of 242 ± 9 pg PGE2/mg protein, whereas 20:4 + rosiglitazone resulted in 322 ± 42 pg PGE2/mg protein, and 20:4 + triacsin C resulted in 396 ± 39 pg PGE2/mg protein.)

Together, these results show that whereas overexpression of ACSL4 blunts PGE2 release, acute inhibition of ACSL4 activity promotes release of PGE2 from human arterial SMCs.

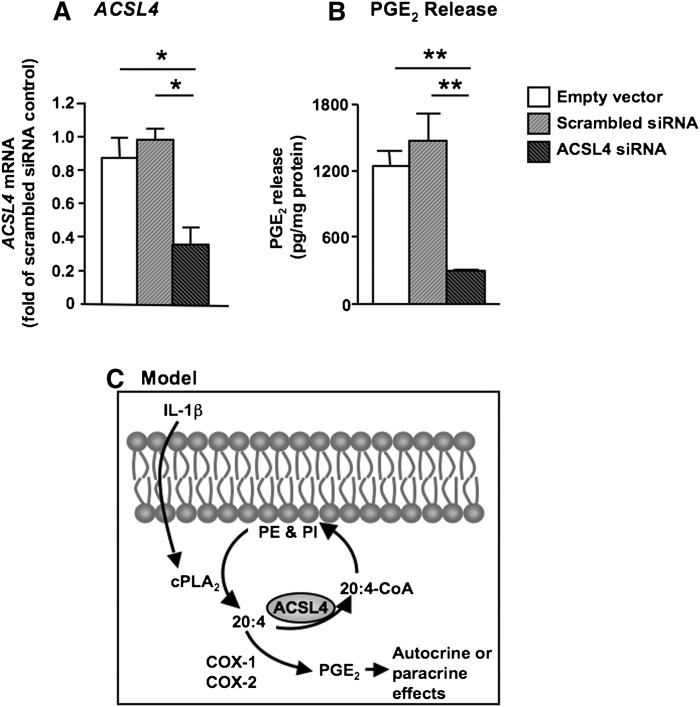

Long-term inhibition of ACSL4 markedly attenuates PGE2 release from SMCs

Long-term downregulation of ACSL4 by small hairpin RNA has recently been shown to reduce secretion of 20:4-derived hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids in breast cancer cell lines (31). We therefore next performed siRNA experiments to stably downregulate ACSL4 by using retroviral constructs and selection of transduced SMCs by puromycin. One of the siRNA constructs tested resulted in a significant 60–70% reduction of ACSL4 mRNA levels, as compared with ACSL4 mRNA levels in SMCs transduced with the empty vector or scrambled siRNA controls (Fig. 7A). ACSL4 siRNA-transduced SMCs grew poorly, consistent with results on breast cancer cells with reduced ACSL4 expression (31), which prevented large-scale experiments. However, it was evident that SMCs stably expressing ACSL4 siRNA exhibited a marked reduction in PGE2 secretion in the presence of 10% serum (Fig. 7B). Thus, long-term inhibition of ACSL4 limits PGE2 release from human SMCs.

Fig. 7.

Sustained downregulation of ACSL4 inhibits PGE2 secretion in SMCs. (A) Immortalized SMCs were transduced with ACSL4 siRNA or the empty vector or a scrambled siRNA control. Levels of ACSL4 mRNA were measured by real-time PCR and were normalized to 18S levels and expressed as fold of scrambled siRNA control. (B) Secreted PGE2 levels were measured in the conditioned media from the different SMCs in A following a 3 day incubation in 10% FBS. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA followed by Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison test (n = 3). (C) Schematic model summarizing the role of ACSL4 in modulating PGE2 production in SMCs. ACSL4 variant 1 is a 20:4-preferring ACSL isoform in human SMCs. The fate of arachidonoyl-CoA generated by ACSL4 is mainly incorporation into PE and PI. Increased ACSL4-mediated incorporation of 20:4 into the phospholipid pool, in turn, reduces the amount of free 20:4 available for PGE2 synthesis in SMCs, whereas acute inhibition of ACSL4 has the opposite effect. However, endogenous ACSL4 is also necessary for PGE2 production, most likely by allowing sufficient 20:4 incorporation into phospholipids.

DISCUSSION

The ACSL4 gene, which is located on the X-chromosome, is ubiquitously expressed, although there appears to be tissue-selective expression of the two ACSL4 splice variants, with the longer ACSL4 variant 2 expressed in the brain (15, 32).

What is known about the biological function of ACSL4? A majority of generated ACSL4-deficient mice die in utero, but surviving ACSL4-hemizygous male mice appear normal (33). However, ACSL4-heterozygous female mice are virtually sterile, perhaps due to the marked morphological changes in the uterine tissue and abnormal degeneration of the corpus luteum in these mice. The numerous uterine proliferative cysts found in ACSL4-heterozygous mice were associated with increased uterine levels of PGE2, 6-keto PGF1α (a stable PGI2 metabolite), and PGF2α, suggesting a possible role for ACSL4 in regulation of prostaglandin production (33). In hepatoma cell lines and breast cancer cell lines, ACSL4 promotes cell proliferation (31, 34). Furthermore, based on correlative studies, ACSL4 has been proposed to promote hepatic TAG synthesis (35, 36), to contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma and adenocarcinoma (37, 38), and to have important effects in cognitive function and neuromuscular disease (15, 39–41). ACSL4 gene expression was also found to be significantly upregulated in livers of insulin-resistant human subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (42), and recently, a polymorphism in ACSL4 was found to be significantly associated with liver fat content (36). The biological function of ACSL4 in SMCs and other vascular cells has been unknown.

We show in the present study that human SMCs express ACSL4 variant 1, and that ACSL4 has a strong preference for 20:4 in intact SMCs. Studies on recombinant ACSL4 have demonstrated that 20:5 (eicosapentaenoic acid), in addition to 20:4, is an excellent substrate for ACSL4 (14). However, 20:5-CoA levels were not detectable in SMCs overexpressing ACSL4, suggesting that 20:5-CoA levels were much lower than those of 20:4-CoA. Conversely, 20:4-CoA was the most-abundant acyl-CoA species detected, and 20:4-CoA levels were dramatically elevated by ACSL4 overexpression. Thus, the effects of ACSL4 in intact cells might depend on FA preference, but also on the abundance of different FAs. The bioavailability of free 20:4 is probably also regulated by ACSL3, which has a high preference for 20:4, at least in vitro (30), and also to a lesser extent by ACSL5 and ACSL1, which are expressed in human SMCs (17). Furthermore, the presence of acyl-CoA thioesterases with different acyl-CoA preferences (43) is likely to play an important role in regulating acyl-CoA levels available for incorporation into different cellular lipid pools.

The results of the present study also demonstrate that whereas overexpression of ACSL4 facilitates 20:4 incorporation into TAG in SMCs, it does not increase TAG mass. Furthermore, ACSL4 does not seem to play a significant role in β-oxidation in SMCs. Thus, rather than promoting neutral lipid loading or cellular energy homeostasis, ACSL4 has an important role as a modulator of eicosanoid synthesis in SMCs. Our results demonstrate that a sustained increase in ACSL4 variant 1 suppresses 20:4- and IL-1β-induced PGE2 release from human arterial SMCs. Most likely, this effect is mediated by competition of ACSL4 with COX-1 and/or COX-2 for free 20:4 taken up by the cell or liberated from the plasma membrane pool (or other lipid pools), increased conversion of this free 20:4 to arachidonoyl-CoA, and subsequently increased incorporation into PE and PI, thus reducing free 20:4 available for eicosanoid synthesis, as depicted in Fig. 7C. In line with our findings in SMCs, overexpression of ACSL4 inhibits PGE2 release from COX-2-overexpressing colon cancer cell lines, most likely by reducing free 20:4 available for PGE2 synthesis (44). In contrast, overexpression of ACSL4 in a breast cancer cell line increases PGE2 secretion, an effect that in part contributed to increased COX-2 expression in ACSL4-overexpressing cells (31). Overexpression of ACSL4 did not affect COX-2 levels in SMCs, which might explain the different findings in SMCs and breast cancer cell lines.

The effects of ACSL4 overexpression on inhibition of PGE2 release were corroborated by the reciprocal increase in PGE2 release in SMCs in which endogenous ACSL4 activity had been acutely inhibited by pharmacological inhibitors. This acute inhibition of ACSL4 activity presumably leads to increased availability of free 20:4 for PGE2 synthesis. The effect of rosiglitazone is most likely mediated by ACSL4 inhibition in the present study because: 1) the same concentration (10 μM) significantly inhibited arachidonoyl-CoA synthesis in SMC lysates; 2) the effects of rosiglitazone on PGE2 release were mimicked by triacsin C, another structurally unrelated ACSL inhibitor; and 3) the effect of rosiglitazone was seen after a short incubation, suggesting that its effects are not due to PPARγ activation.

In contrast, sustained downregulation of ACSL4 resulted in a markedly reduced PGE2 release, which is consistent with the recent study on breast cancer cell lines by Maloberti et al. (31). We propose a model in which endogenous continuous ACSL4-mediated arachidonoyl-CoA synthesis is required for incorporation of 20:4 into phospholipids and subsequent PGE2 synthesis, whereas acute inhibition of ACSL4 increases the free 20:4 available as a substrate for COX-1/2 and PGE2 synthesis (Fig. 7C). Together, our results suggest that endogenous ACSL4 plays an important role as a regulator of prostaglandin secretion from SMCs, which might regulate SMC proliferation, release of inflammatory mediators, or other processes in the vascular wall.

Interestingly, ACSL4 has been suggested to be reduced in unstable atherosclerotic plaques compared with stable plaques (45), raising the possibility that ACSL4 contributes to atherosclerotic disease in humans. It is possible, therefore, that ACSL4 in SMCs directly contributes to regulation of eicosanoid release from SMCs and their downstream effects in cell types within the vascular wall or lesions of atherosclerosis. For example, PGE2 increases permeability of endothelial cell cultures (46), and long-term exposure of human monocytes/macrophages to PGE2 enhances chemokine expression in these cells (47). Mouse models with smooth muscle-targeted ACSL4 deficiency would shed light onto the probable role of SMC ACSL4 in vascular injury or atherosclerosis.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ACSL

- long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase

- COX

- cyclooxygenase

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- DHA

- docosahexaenoic acid

- eGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FATP

- FA transport protein

- IL-1β

- interleukin-1β

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PGE2

- prostaglandin E2

- PI

- phosphatidylinositol

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- TAG

- triacylglycerol

These studies were supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-062887, HL-092969 (Project 2), HL-097365 (K.E.B.), and DK-082841 (S.P.). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other granting agencies.Some of the real-time PCR results were generated by the Virus, Molecular Genetics, and Cell Core of the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center at the University of Washington, supported by grant P30 DK17047. Acyl-CoAs were analyzed by the Molecular Phenotyping Core, Michigan Nutrition and Obesity Research Center, supported by grant P30 DK089503. The pBM-I-eGFP vector was generously provided by Dr. G. Nolan (Stanford University, Stanford, CA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Natarajan R., Nadler J. L. 2004. Lipid inflammatory mediators in diabetic vascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 1542–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth E. M., Grosser T., Wang M., Yu Y., FitzGerald G. A. 2009. Prostanoids in health and disease. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl): 423–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang M., Song W. L., Cheng Y., Fitzgerald G. A. 2008. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 inhibition in cardiovascular inflammatory disease. J. Intern. Med. 263: 500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bäck M., Hansson G. K. 2006. Leukotriene receptors in atherosclerosis. Ann. Med. 38: 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi T., Tahara Y., Matsumoto M., Iguchi M., Sano H., Murayama T., Arai H., Oida H., Yurugi-Kobayashi T., Yamashita J. K., et al. 2004. Roles of thromboxane A(2) and prostacyclin in the development of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 114: 784–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M., Zukas A. M., Hui Y., Ricciotti E., Puré E., FitzGerald G. A. 2006. Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 augments prostacyclin and retards atherogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103: 14507–14512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doran A. C., Meller N., McNamara C. A. 2008. Role of smooth muscle cells in the initiation and early progression of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28: 812–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graves L. M., Bornfeldt K. E., Sidhu J. S., Argast G. M., Raines E. W., Ross R., Leslie C. C., Krebs E. G. 1996. Platelet-derived growth factor stimulates protein kinase A through a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway in human arterial smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libby P., Warner S. J., Friedman G. B. 1988. Interleukin 1: a mitogen for human vascular smooth muscle cells that induces the release of growth-inhibitory prostanoids. J. Clin. Invest. 81: 487–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bornfeldt K. E., Campbell J. S., Koyama H., Argast G. M., Leslie C. C., Raines E. W., Krebs E. G., Ross R. 1997. The mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway can mediate growth inhibition and proliferation in smooth muscle cells. Dependence on the availability of downstream targets. J. Clin. Invest. 100: 875–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman R. A., Lewin T. M., Van Horn C. G., Gonzalez-Baró M. R. 2002. Do long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases regulate fatty acid entry into synthetic versus degradative pathways? J. Nutr. 132: 2123–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewin T. M., Kim J. H., Granger D. A., Vance J. E., Coleman R. A. 2001. Acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms 1, 4, and 5 are present in different subcellular membranes in rat liver and can be inhibited independently. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 24674–24679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins P. A., Maiguel D., Jia Z., Pevsner J. 2007. Evidence for 26 distinct acyl-coenzyme A synthetase genes in the human genome. J. Lipid Res. 48: 2736–2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang M. J., Fujino T., Sasano H., Minekura H., Yabuki N., Nagura H., Iijima H., Yamamoto T. T. 1997. A novel arachidonate-preferring acyl-CoA synthetase is present in steroidogenic cells of the rat adrenal, ovary, and testis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94: 2880–2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meloni I., Muscettola M., Raynaud M., Longo I., Bruttini M., Moizard M. P., Gomot M., Chelly J., des Portes V., Fryns J. P., et al. 2002. FACL4, encoding fatty acid-CoA ligase 4, is mutated in nonspecific X-linked mental retardation. Nat. Genet. 30: 436–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mashek D. G., Bornfeldt K. E., Coleman R. A., Berger J., Bernlohr D. A., Black P., DiRusso C. C., Farber S. A., Guo W., Hashimoto N., et al. 2004. Revised nomenclature for the mammalian long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase gene family. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1958–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Askari B., Kanter J. E., Sherrid A. M., Golej D. L., Bender A. T., Liu J., Hsueh W. A., Beavo J. A., Coleman R. A., Bornfeldt K. E. 2007. Rosiglitazone inhibits acyl-CoA synthetase activity and fatty acid partitioning to diacylglycerol and triacylglycerol via a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-independent mechanism in human arterial smooth muscle cells and macrophages. Diabetes. 56: 1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki L. A., Poot M., Gerrity R. G., Bornfeldt K. E. 2001. Diabetes accelerates smooth muscle accumulation in lesions of atherosclerosis: lack of direct growth-promoting effects of high glucose levels. Diabetes. 50: 851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez-Reyes N., Halbert C. L., Smith P. P., Benditt E. P., McDougall J. K. 1992. Immortalization of primary human smooth muscle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89: 1224–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garton K. J., Ferri N., Raines E. W. 2002. Efficient expression of exogenous genes in primary vascular cells using IRES-based retroviral vectors. Biotechniques. 32: 830, 832, 834 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rozen S., Skaletsky H. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132: 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes C. A., Allegood J. C., Sims K., Wang E. W., Sullards M. C., Merrill A. H., Jr 2008. Quantitation of fatty acyl-coenzyme As in mammalian cells by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Lipid Res. 49: 1113–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golovko M. Y., Murphy E. J. 2004. An improved method for tissue long-chain acyl-CoA extraction and analysis. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1777–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewin T. M., Wang S., Nagle C. A., Van Horn C. G., Coleman R. A. 2005. Mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase-1 directs the metabolic fate of exogenous fatty acids in hepatocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 288: E835–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37: 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Askari B., Carroll M. A., Capparelli M., Kramer F., Gerrity R. G., Bornfeldt K. E. 2002. Oleate and linoleate enhance the growth-promoting effects of insulin-like growth factor-I through a phospholipase D-dependent pathway in arterial smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 36338–36344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton J. G., Comai K. 1984. Separation of neutral lipids and free fatty acids by high-performance liquid chromatography using low wavelength ultraviolet detection. J. Lipid Res. 25: 1142–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidlin F., Loeffler S., Bertrand C., Landry Y., Gies J. P. 2000. PLA2 phosphorylation and cyclooxygenase-2 induction, through p38 MAP kinase pathway, is involved in the IL-1β-induced bradykinin B2 receptor gene transcription. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 361: 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J. H., Lewin T. M., Coleman R. A. 2001. Expression and characterization of recombinant rat Acyl-CoA synthetases 1, 4, and 5. Selective inhibition by triacsin C and thiazolidinediones. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 24667–24673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Horn C. G., Caviglia J. M., Li L. O., Wang S., Granger D. A., Coleman R. A. 2005. Characterization of recombinant long-chain rat acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms 3 and 6: identification of a novel variant of isoform 6. Biochemistry. 44: 1635–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maloberti P. M., Duarte A. B., Orlando U. D., Pasqualini M. E., Solano A. R., López-Otín C., Podestá E. J. 2010. Functional interaction between acyl-CoA synthetase 4, lipooxygenases and cyclooxygenase-2 in the aggressive phenotype of breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 5: e15540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao Y., Traer E., Zimmerman G. A., McIntyre T. M., Prescott S. M. 1998. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of human long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 (FACL4). Genomics. 49: 327–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho Y. Y., Kang M. J., Sone H., Suzuki T., Abe M., Igarashi M., Tokunaga T., Ogawa S., Takei Y. A., Miyazawa T., et al. 2001. Abnormal uterus with polycysts, accumulation of uterine prostaglandins, and reduced fertility in mice heterozygous for acyl-CoA synthetase 4 deficiency. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284: 993–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang Y. C., Wu C. H., Chu J. S., Wang C. K., Hung L. F., Wang Y. J., Ho Y. S., Chang J. G., Lin S. Y. 2005. Involvement of fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 in hepatocellular carcinoma growth: roles of cyclic AMP and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. World J. Gastroenterol. 11: 2557–2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kudo T., Tamagawa T., Kawashima M., Mito N., Shibata S. 2007. Attenuating effect of clock mutation on triglyceride contents in the ICR mouse liver under a high-fat diet. J. Biol. Rhythms. 22: 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kotronen A., Yki-Järvinen H., Aminoff A., Bergholm R., Pietiläinen K. H., Westerbacka J., Talmud P. J., Humphries S. E., Hamsten A., Isomaa B., et al. 2009. Genetic variation in the ADIPOR2 gene is associated with liver fat content and its surrogate markers in three independent cohorts. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 160: 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sung Y. K., Hwang S. Y., Park M. K., Bae H. I., Kim W. H., Kim J. C., Kim M. 2003. Fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 is overexpressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 94: 421–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao Y., Dave K. B., Doan T. P., Prescott S. M. 2001. Fatty acid CoA ligase 4 is up-regulated in colon adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 61: 8429–8434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piccini M., Vitelli F., Bruttini M., Pober B. R., Jonsson J. J., Villanova M., Zollo M., Borsani G., Ballabio A., Renieri A. 1998. FACL4, a new gene encoding long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4, is deleted in a family with Alport syndrome, elliptocytosis, and mental retardation. Genomics. 47: 350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhat S. S., Schmidt K. R., Ladd S., Kim K. C., Schwartz C. E., Simensen R. J., DuPont B. R., Stevenson R. E., Srivastava A. K. 2006. Disruption of DMD and deletion of ACSL4 causing developmental delay, hypotonia, and multiple congenital anomalies. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 112: 170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meloni I., Parri V., De Filippis R., Ariani F., Artuso R., Bruttini M., Katzaki E., Longo I., Mari F., Bellan C., et al. 2009. The XLMR gene ACSL4 plays a role in dendritic spine architecture. Neuroscience. 159: 657–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westerbacka J., Kolak M., Kiviluoto T., Arkkila P., Sirén J., Hamsten A., Fisher R. M., Yki-Järvinen H. 2007. Genes involved in fatty acid partitioning and binding, lipolysis, monocyte/macrophage recruitment, and inflammation are overexpressed in the human fatty liver of insulin-resistant subjects. Diabetes. 56: 2759–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirkby B., Roman N., Kobe B., Kellie S., Forwood J. K. 2010. Functional and structural properties of mammalian acyl-coenzyme A thioesterases. Prog. Lipid Res. 49: 366–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao Y., Pearman T., Zimmerman G. A., McIntyre T. M., Prescott S. M. 2000. Intracellular unesterified arachidonic acid signals apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97: 11280–11285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cipollone F., Rocca B., Patrono C. 2004. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression and inhibition in atherothrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreno J. J. 2009. Differential effects of arachidonic and eicosapentaenoic acid-derived eicosanoids on polymorphonuclear transmigration across endothelial cell cultures. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 331: 1111–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hertz A. L., Bender A. T., Smith K. C., Gilchrist M., Amieux P. S., Aderem A., Beavo J. A. 2009. Elevated cyclic AMP and PDE4 inhibition induce chemokine expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106: 21978–21983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]