Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate whether ratings on Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) items related to instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) are associated with cognitive or brain morphometric characteristics of participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and global CDR scores of 0.5.

Methods:

Baseline cognitive and morphometric data were analyzed for 283 individuals with MCI who were divided into 2 groups (impaired and intact) based on their scores on the 3 CDR categories assessing IADL. Rates of progression to Alzheimer disease (AD) over 2 years were also compared in the 2 groups.

Results:

The impaired IADL MCI group showed a more widespread pattern of gray matter loss involving frontal and parietal regions, worse episodic memory and executive functions, and a higher percentage of individuals progressing to AD than the relatively intact IADL MCI group.

Conclusions:

The results demonstrate the importance of considering functional information captured by the CDR when evaluating individuals with MCI, even though it is not given equal weight in the assignment of the global CDR score. Worse impairment on IADL items was associated with greater involvement of brain regions beyond the mesial temporal lobe. The conventional practice of relying on the global CDR score as currently computed underutilizes valuable IADL information available in the scale, and may delay identification of an important subset of individuals with MCI who are at higher risk of clinical decline.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is an established risk state for the development of Alzheimer disease (AD).1 The requirement that functional activities remain essentially intact was originally considered central for differentiating MCI from mild dementia. However, recent studies have shown that subtle changes in the ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) occur in MCI.2–6

The designation of MCI is often supported by a global rating of 0.5 on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)7 scale. The most heavily weighted component of the global CDR score is memory function; nonmemory components, including the 3 IADL categories, receive less weighting. Consequently, 2 individuals with MCI receiving the same global CDR score can noticeably differ in IADL performance. This lack of richness in characterizing IADL changes might prevent identification of meaningful clinical differences in individuals with MCI. To address this possibility, we compared baseline brain morphometry, cognition, and 2-year clinical outcome in subgroups of MCI participants who had global CDR scores of 0.5 but who differed with regard to IADL items. We predicted that, relative to individuals with intact IADL, those with relatively impaired IADL would show 1) a more widespread pattern of cortical atrophy involving frontal regions in addition to the expected medial temporal lobe involvement, 2) poorer cognitive performance, especially on tests of executive function, and 3) a higher rate of progression to probable AD.

METHODS

Raw data used in the current study were obtained from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (www.loni.ucla.edu\ADNI). ADNI was launched in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the Food and Drug Administration, private pharmaceutical companies, and nonprofit organizations, as a $60 million, 5-year public–private partnership. ADNI's goal is to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. Determination of sensitive and specific markers of very early AD progression is intended to aid researchers and clinicians to develop new treatments and monitor their effectiveness, as well as lessen the time and cost of clinical trials.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

This study was approved by an ethical standards committee on human experimentation at each institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or authorized representatives participating in the study.

Participants.

ADNI eligibility criteria are described at http://www.adni-info.org/Scientists/ADNIGrant/ProtocolSummary.aspx. Briefly, participants were 55–90 years old, nondepressed, with a modified Hachinski score of 4 or less, and a study partner able to provide an independent evaluation of functioning. Individuals with a history of significant neurologic or psychiatric disease, substance abuse, or metal in their body other than dental fillings were excluded.

Healthy control (HC) participants had Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of 24–30, normal activities of daily living (ADL) as assessed with the Functional Activity Questionnaire (FAQ, clinical judgment without suggested cutoff), a global CDR score of 0, and normal memory function, as indicated by education-adjusted scores on the modified Wechsler Memory Scale Logical Memory II (LM II, story A only) (i.e., a score >8 for individuals with ≥16 years of education; >4 for individuals with 8–15 years of education; and >2 for individuals with 0–7 years of education). MCI participants had a subjective memory complaint, objective memory loss as indicated by education-adjusted scores on the LM II (score ≤8 for individuals with ≥16 years of education; ≤4 for individuals with 8–15 years of education; and ≤2 for individuals with 0–7 years of education), a global CDR score of 0.5 and a score ≥0.5 on the memory box of the CDR, essentially preserved ADL primarily assessed by the FAQ, and an absence of dementia.1

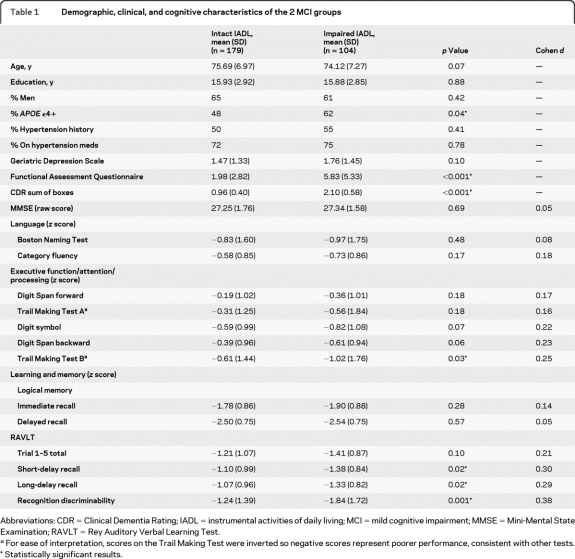

This study included individuals classified as HC or MCI within ADNI with baseline MRI scans that passed local quality inspection. We excluded 7 HC who converted to MCI at any follow-up visit to minimize the possibility of misclassification of HC participants at baseline. The present study thus consisted of 202 HC and 283 MCI participants. MCI participants were divided into 2 subgroups (intact IADL and impaired IADL) based on their scores on the 3 CDR categories assessing IADL (i.e., judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies). Specifically, the intact IADL group (n = 179) consisted of individuals with a rating of 0 on all 3 IADL categories or a rating of 0.5 on 1 of the 3 categories; the impaired IADL group (n = 104) consisted of individuals with a rating of 0.5 on 2 or more of the 3 IADL categories or a rating of 1 on any 1 of the categories. The 2 MCI groups did not differ in age (t281 = 1.79, p = 0.07), level of education (t281 = 0.15, p = 0.88), sex distribution (χ2 (1) = 0.65, p = 0.42), history of hypertension (χ2 (1) = 0.67, p = 0.41), use of hypertension medications (χ2 (1) = 0.08, p = 0.78), or scores on the Geriatric Depression Scale (t281 = −1.67, p = 0.10). The impaired IADL group demonstrated higher FAQ scores (t281 = −7.95, p < 0.001) and a higher frequency of APOE ϵ4 carriers relative to the intact IADL group (χ2 (1) = 3.95, p = 0.04; table 1). Two-year follow-up clinical outcome data (i.e., reversion to normal cognitive status, stable MCI, or progression to probable AD) were available for 233 of the MCI participants. The determination of progression to probable AD was based on National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria (see appendix e-2 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org for operational criteria).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and cognitive characteristics of the 2 MCI groups

Abbreviations: CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

For ease of interpretation, scores on the Trail Making Test were inverted so negative scores represent poorer performance, consistent with other tests.

Statistically significant results.

Neuropsychological assessment.

All participants were administered a cognitive battery as previously described.8,9 Measures included MMSE,10 Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised (WAIS-R) Digit Span and Digit Symbol subtests, Boston Naming Test (BNT),11 animal fluency, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT),12 the LM II,13 and the Trail Making Test.14

Magnetic resonance scanning and brain morphometry.

Dual 3-dimensional T1-weighted volumes were downloaded from the public ADNI database (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Data/index.shtml). All image processing and analyses occurred at the Multimodal Imaging Laboratory, University of California, San Diego. Images were corrected for gradient nonlinearities15 and intensity nonuniformity.16 The 2 images were aligned, averaged to improve signal-to-noise ratio, and resampled to isotropic 1-mm voxels. Methods based on FreeSurfer software were used to obtain cortical gray matter volume and thickness measures in distinct regions of interest (ROIs).17–22

To limit the number of statistical comparisons, analyses only included regions assumed to be involved in early AD pathology,23 such as bilateral hippocampal formation (volumetric measures) and regions of temporal, frontal, parietal, and cingulate cortex (thickness measures) (see ROIs listed in table e-1). The caudal and rostral anterior cingulate regions were combined as anterior cingulate cortex (ACC); the isthmus and posterior cingulate regions were combined as posterior cingulate cortex (PCC).

Statistical analysis.

Group comparisons were performed with separate independent sample t tests or χ2 tests for demographic, cognitive, and clinical outcome variables. Cognitive test scores for MCI participants were converted to z scores based upon the mean and SD of the HC group (means and standard deviations of the raw test scores for MCI and HC groups are shown in table e-2). Because the impaired IADL group had more APOE ϵ4 carriers than the intact group, analyses of cognitive variables were also performed with separate one-way analyses of covariance, controlling for APOE genotype. Although some of the distributions of scores on cognitive tests were skewed, we did not transform the data since the sample size was sufficiently robust to enable appropriate use of the t statistic.24

Differences in morphometric variables among HC, intact IADL MCI, and impaired IADL MCI groups were assessed with multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) followed by univariate analyses of variance with Bonferroni adjustments for Type I error (α = 0.001) (table e-1). Pairwise comparisons were conducted through separate independent sample t tests (α = 0.05). Effects of age and gender were regressed from all thickness and volumetric measures and standardized residual values (i.e., z scores) were used for analyses. Hippocampal volumes were also corrected for differences in head size by regressing the estimated total cranial vault volume.25 Results controlling for APOE status are only reported if they differed from noncontrolled analyses. Effect sizes were calculated with Cohen d for significant group differences on cognitive and morphometric measures. All analyses were conducted in SPSS (version 17.0).

RESULTS

Neuropsychological differences.

Performance did not differ between MCI groups on MMSE, Digit Span forward and backward, Trail Making Test Part A, Digit Symbol, LM immediate and delayed recall, RAVLT Trials 1–5 total learning score, animal fluency, or BNT. However, the impaired IADL group demonstrated poorer performance than the intact IADL group on the Trail Making Test Part B (t281 = −2.13, p = 0.03), RAVLT short (t281 = 2.45, p = 0.02) and long (t281 = 2.39, p = 0.02) delayed recall, and RAVLT recognition discriminability (t281 = 3.22, p = 0.001) (table 1).

When APOE status was included as a covariate, the same pattern of findings was observed except that Digit Symbol, which was marginally significant before, now reached significance (F1,271 = 4.73, p = 0.03).

Regional differences in morphometry.

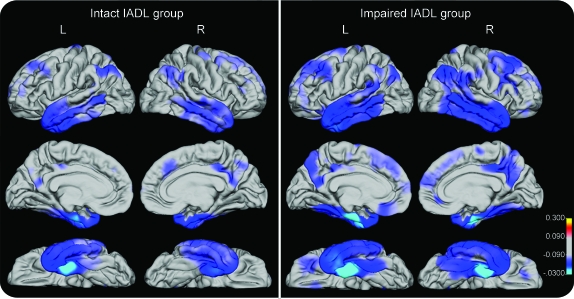

The overall MANOVA for group effects on all ROIs was significant (Wilks lambda = 0.64, F72,896 = 3.06, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.19). Follow-up univariate analyses comparing the MCI groups to the HC group showed that both MCI groups had smaller than normal hippocampal volumes bilaterally and thinner than normal cortex in frontal (i.e., bilateral caudal and rostral middle frontal, superior frontal, and right lateral orbitofrontal areas), temporal (i.e., bilateral entorhinal cortex, parahippocampal, superior, middle, and inferior temporal, and temporal pole areas), and parietal (i.e., bilateral inferior parietal lobule and left supramarginal) regions, as well as in the bilateral PCC. Moreover, the impaired IADL group—but not the intact IADL group—showed cortical thinning in bilateral medial orbitofrontal, pars orbitalis, and right supramarginal regions. Information on magnetic resonance morphometric measures for the 3 groups in all ROIs are presented in table e-1.

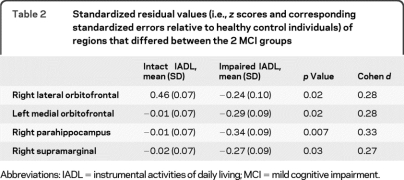

The 2 MCI groups showed comparable hippocampal volumes and similar cortical thickness in entorhinal, lateral temporal, dorsolateral prefrontal, and cingulate ROIs bilaterally. However, the impaired IADL group had reduced cortical thickness in left medial orbitofrontal (t281 = 2.29, p = 0.02), right lateral orbitofrontal (t281 = 2.32, p = 0.02), right parahippocampus (t281 = 2.71, p = 0.007), and right supramarginal regions (t281 = 2.25, p = 0.03) compared to the intact IADL group (table 2 and figure).

Table 2.

Standardized residual values (i.e., z scores and corresponding standardized errors relative to healthy control individuals) of regions that differed between the 2 MCI groups

Abbreviations: IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; MCI = mild cognitive impairment.

Figure. Reconstructed cortical surface maps for the 2 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) groups relative to the healthy control (HC) group.

Reconstructed cortical surface maps representing the average mean difference in thickness (mm, p < 0.001) for the 2 MCI groups, relative to the HC group, after controlling for the effects of age and gender. Blue and cyan indicate thinning. IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

Longitudinal progression rates.

Two-year rate of progression to AD was higher in the impaired IADL group (46%; 41/89 participants) than in the intact group (31%; 45/144 participants; χ2(1, n = 233) = 5.19, p = 0.02).

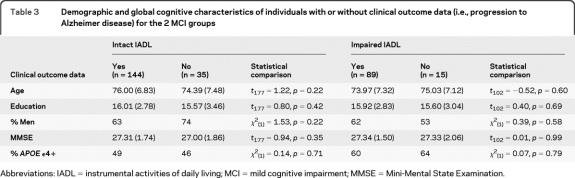

MCI participants with or without clinical outcome data did not differ in age, education level, gender distribution, APOE ϵ4 status, or MMSE scores (all p values >0.05; table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic and global cognitive characteristics of individuals with or without clinical outcome data (i.e., progression to Alzheimer disease) for the 2 MCI groups

Abbreviations: IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

DISCUSSION

When MCI participants with global CDR scores of 0.5, CDR memory ratings of 0.5, and impaired performance on the LM II were divided into groups with relatively intact or impaired ratings on the CDR IADL components, those with impaired IADL ratings exhibited poorer cognitive test performance, more widespread gray matter thinning in frontal and parietal lobe brain regions, and a higher rate of progression to probable AD over a 2-year follow-up period. Group differences in cognitive test performance were apparent on tests of executive function (i.e., TMT-B and Digit Symbol test) and episodic memory (i.e., RAVLT). Differences on episodic memory measures were somewhat unexpected since all participants had CDR memory ratings of 0.5 and groups did not differ in degree of atrophy in mesial temporal lobe structures implicated in memory (i.e., hippocampus and entorhinal cortices), or on performance on the LM II. Although the RAVLT, an unstructured list-learning task, may simply be a more sensitive measure of episodic memory than the LM II, a structured story-memory task, it is possible that the worse performance of the IADL-impaired group on the RAVLT is related to their greater deficit in executive functions. Although memory for complex narrative such as that required by the LM II is impaired in patients with frontal lobe lesions,26 the RAVLT may place greater demands on executive abilities for organizing the unstructured word-list material during encoding or for strategic search during retrieval.27 We previously found that MCI participants with impaired executive function performed more poorly on the RAVLT, but not on the LM II, than did MCI participants without executive dysfunction, and that thinning in frontal areas contributed to RAVLT performance beyond the well-known contribution of medial temporal structures.27 These subtle distinctions between memory measures are not likely to be made within the CDR because memory ability is assessed as an overall rating based on the subjective judgment of an informant and does not take into account various cognitive processes underlying objective memory performance.

Morphometric analyses showed that the impaired IADL group had greater and more widespread atrophy than the intact IADL group in left medial orbitofrontal, right lateral orbitofrontal, right supramarginal, and right parahippocampal cortex. The bilateral involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex is consistent with a recent study that highlighted the role of ventromedial prefrontal regions in carrying out complex cognitive and emotional tasks encountered in everyday life.28 Greater cortical thinning in frontal regions in the impaired IADL group than in the intact group is consistent with their poorer performance on measures of executive function. The finding that cortical thickness was thinner in the right supramarginal and parahippocampal areas in the impaired IADL group than in the intact group is consistent with recent results that suggest brain atrophy spreads from medial temporal lobe structures to parietal and frontal cortical regions as severity of MCI increases,29 and with the typical distribution of AD neuropathology early in the disease process.30

Consistent with previous studies,2,3,5 MCI participants with impaired IADL were more likely than those with intact IADL to progress to a clinical diagnosis of probable AD within the next 2 years. The 2 MCI subgroups may thus represent points along an MCI-to-AD continuum with the impaired IADL group having progressed farther toward AD than the intact IADL group. The higher scores on the FAQ in the impaired than the intact IADL group is consistent with this. It could be argued that the presence of deficits in 2 or more areas of cognition (episodic memory and executive function), coupled with impaired IADL, would support a diagnosis of mild dementia rather than MCI. However, the conventional practice of relying on summary screening measures and rating scales such as the MMSE, LM, and CDR to differentiate MCI from AD suffers from a certain granularity31 and fails to capture the subtle but significant cognitive and functional changes in early dementia. Alternative approaches that incorporate more comprehensive neuropsychologically based methods for the diagnosis of MCI and AD have recently shown advantage in improving the stability and reliability of a diagnosis that predicts clinical decline.32–35

Global CDR score is one of the most commonly used measures for identifying and staging MCI or AD dementia. There are, however, a number of problems that have been pointed out36–39 with regard to the established methods for computing a global CDR. These include inconsistency in ratings across features (e.g., rating of memory vs other cognitive features or function) and a lack of precision in detecting or scaling levels of impairment within a particular CDR category (e.g., 0.5) or with progression. Indeed, in the present study we found that, despite comparable global CDR scores, MCI groups that differed in IADL CDR subratings had meaningful differences in baseline cognitive performance, brain morphometry, and rate of progression to AD. This suggests that the global CDR score is not sensitive enough to distinguish levels of severity or predict progression within MCI cohorts. The present findings support studies that propose alternative algorithms38,39 to overcome this lack of sensitivity. One such algorithm is the CDR sum of boxes (SB), which has been used in several recent studies to increase the ability to discriminate MCI from very early AD and track disease progression.36,39,40 Though conceptually different from the CDR-SB, our results coincide with studies that show higher CDR-SB scores predict higher rates of progression to AD.36,39

A limitation of the current study is that 2-year clinical outcome data were available for only 82% of individuals with MCI at the time we conducted this study. However, MCI participants with clinical outcome data did not significantly differ from those without outcome data on any baseline demographic or global cognitive characteristic, making it unlikely that selective attrition biased the results. Another limitation inherent to the CDR is that changes in IADL abilities are based solely on an informant's report and may be subject to reporter bias. Objective assessment of functional abilities such as subject-performed tasks might provide better discrimination between MCI subgroups and have greater predictive ability. Additionally, histopathologic verification of disease is lacking; some MCI participants may have disorders other than or in addition to AD, which might explain, in part, some of the differences observed between the 2 MCI groups. Finally, diagnosticians had access to all CDR data when making a determination of conversion to dementia, and thus could conceivably have used baseline CDR IADLs when making the diagnosis of dementia at follow-up. However, since the same inclusion/exclusion criteria (i.e., global CDR of 0.5 and CDR memory of 0.5) were applied to all MCI participants at baseline, it is more likely that the determination of functional impairment of sufficient severity to interfere with daily life was based on follow-up FAQ and global CDR scores.

The present findings demonstrate that the readily available informant-based information on IADL incorporated in a baseline administration of the CDR is useful for identifying subgroups of individuals with MCI who have more widespread neurodegeneration and are more likely to progress to probable AD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Alain Koyama, Robin G. Jennings, Michele Perry, Chris Pung, and Elaine Wu for downloading and preprocessing the ADNI MRI data.

- ACC

- anterior cingulate cortex

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- ADL

- activities of daily living

- ADNI

- Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

- BNT

- Boston Naming Test

- CDR

- Clinical Dementia Rating

- FAQ

- Functional Activity Questionnaire

- HC

- healthy control

- IADL

- instrumental activities of daily living

- LM II

- Logical Memory II

- MANOVA

- multivariate analysis of variance

- MCI

- mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE

- Mini-Mental State Examination

- PCC

- posterior cingulate cortex

- RAVLT

- Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test

- ROI

- region of interest

- SB

- sum of boxes

- WAIS-R

- Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised.

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Coinvestigators are listed in appendix e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (www.loni.ucla.edu\ADNI). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators is available online.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analysis was conducted by Dr. Yu-Ling Chang.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by the NIH (NIA R01 AG012674, NIA R01 AG031224, P30 AG010129, and K01 AG030514) and the Dana Foundation. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (NIH U01 AG024904). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai Inc., Elan Corporation, Genentech, Inc., GE Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Innogenetics, Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly and Company, Medpace Inc., Merck and Co., Inc., Novartis, Pfizer Inc., Roche, Schering-Plough Corp., SYNARC, Inc., and Wyeth, as well as nonprofit partners the Alzheimer's Association and Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation, with participation from the US Food and Drug Administration. Private sector contributions to ADNI are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of California, Los Angeles.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Chang receives research support from Alzheimer's Association Young Investigator Award and the Stein Institute for Research on Aging, University of California San Diego (UCSD). Dr. Bondi serves as served as an Associate Editor for the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society; and receives research support from the Alzheimer's Association and the NIH/NIA. Dr. McEvoy receives research support from the NIH; and her spouse is president of and holds stock and stock options in Cortechs Labs, Inc. Dr. Fennema-Notestine receives research support from the NIH, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Alzheimer's Association. Dr. Salmon has received a speaker honorarium from Kaiser-Permanente San Diego; serves as a consultant for CHDI Foundation, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and receives research support from the NIH. Dr. Galasko serves on a scientific advisory board for Janssen/Elan Corporation; serves as Co-Editor for Alzheimer's Research and Therapy; serves as a consultant for United BioSource Corporation; and receives research support from Eli Lilly and Company and the NIH/NIA. Dr. Hagler has a patent pending re: Automated method for labeling white matter fibers from MRI; and receives research support from the NIH. Dr. Dale receives research support from the NIH; receives funding to his laboratory from General Electric Medical Systems as part of a Master Research Agreement with UCSD; and is a founder of, holds equity in, and serves on the scientific advisory board for CorTechs Labs, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2001;58:1985–1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tabert MH, Albert SM, Borukhova-Milov L, et al. Functional deficits in patients with mild cognitive impairment: prediction of AD. Neurology 2002;58:758–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peres K, Chrysostome V, Fabrigoule C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Restriction in complex activities of daily living in MCI: impact on outcome. Neurology 2006;67:461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bangen KJ, Jak AJ, Schiehser DM, et al. Complex activities of daily living vary by mild cognitive impairment subtype. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2010;16:630–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pereira FS, Yassuda MS, Oliveira AM, et al. Profiles of functional deficits in mild cognitive impairment and dementia: benefits from objective measurement. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2010;16:297–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment–beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med 2004;256:240–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982;140:566–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer's Disease Centers' Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:91–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology 2010;74:201–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rey A. l'Examen psychologique dans les cas d'encephalopathie traumatique. Arch Psychol 1941;28:286–340 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation, 2nd ed. Tempe, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jovicich J, Czanner S, Greve D, et al. Reliability in multi-site structural MRI studies: effects of gradient non-linearity correction on phantom and human data. Neuroimage 2006;30:436–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1998;17:87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 2002;33:341–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:11050–11055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis: II: inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage 1999;9:195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fischl B, Sereno MI, Tootell RB, Dale AM. High-resolution intersubject averaging and a coordinate system for the cortical surface. Hum Brain Mapp 1999;8:272–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 2006;31:968–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis: I: segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage 1999;9:179–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fennema-Notestine C, Hagler DJ, Jr, McEvoy LK, et al. Structural MRI biomarkers for preclinical and mild Alzheimer's disease. Hum Brain Mapp 2009;30:3238–3253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lumley T, Diehr P, Emerson S, Chen L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annu Rev Public Health 2002;23:151–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buckner RL, Head D, Parker J, et al. A unified approach for morphometric and functional data analysis in young, old, and demented adults using automated atlas-based head size normalization: reliability and validation against manual measurement of total intracranial volume. Neuroimage 2004;23:724–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zalla T, Phipps M, Grafman J. Story processing in patients with damage to the prefrontal cortex. Cortex 2002;38:215–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chang YL, Jacobson MW, Fennema-Notestine C, et al. Level of executive function influences verbal memory in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and predicts prefrontal and posterior cingulate thickness. Cereb Cortex 2010;20:1305–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cato MA, Delis DC, Abildskov TJ, Bigler E. Assessing the elusive cognitive deficits associated with ventromedial prefrontal damage: a case of a modern-day Phineas Gage. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2004;10:453–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Whitwell JL, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, et al. 3D maps from multiple MRI illustrate changing atrophy patterns as subjects progress from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2007;130:1777–1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991;82:239–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: ten years later. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1447–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saxton J, Snitz BE, Lopez OL, et al. Functional and cognitive criteria produce different rates of mild cognitive impairment and conversion to dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:737–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jak AJ, Urban S, McCauley A, et al. Profile of hippocampal volumes and stroke risk varies by neuropsychological definition of mild cognitive impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2009;15:890–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Loewenstein DA, Acevedo A, Small BJ, Agron J, Crocco E, Duara R. Stability of different subtypes of mild cognitive impairment among the elderly over a 2- to 3-year follow-up period. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2009;27:418–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chang YL, Bondi MW, Fennema-Notestine C, et al. Brain substrates of learning and retention in mild cognitive impairment diagnosis and progression to Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia 2010;48:1237–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Daly E, Zaitchik D, Copeland M, Schmahmann J, Gunther J, Albert M. Predicting conversion to Alzheimer disease using standardized clinical information. Arch Neurol 2000;57:675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gelb DJ. Measurement of progression in Alzheimer's disease: a clinician's perspective. Stat Med 2000;19:1393–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gelb DJ, St Laurent RT. Alternative calculation of the global clinical dementia rating. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1993;7:202–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Bryant SE, Waring SC, Cullum CM, et al. Staging dementia using Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes scores: a Texas Alzheimer's research consortium study. Arch Neurol 2008;65:1091–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, et al. Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol 2004;61:59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.