Abstract

In this paper, we analyse the life history narratives of 10 poor gay and bisexual Black men over the age of 50 living with HIV/AIDS in New York City, focusing on experiences of stigma. Three overarching themes are identified. First, participants described the ways in which stigma marks them as just one more body within social and medical institutions, emphasising the dehumanisation they experience in these settings. Second, respondents described the process of knowing your place within social hierarchies as a means through which they are rendered tolerable. Finally, interviewees described the dynamics of stigma as all-consuming, relegating them to the quagmire of an HIV ghetto. These findings emphasise that despite advances in treatment and an aging population of persons living with HIV, entrenched social stigmas continue to endanger the well-being of Black men who have sex with men.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, stigma, social inequality, gay and bisexual men, Black MSM

Introduction

The prevalence of HIV infection in marginalised subgroups in the USA surpasses that in some of the most resource poor settings globally, leading some to argue that the domestic HIV/AIDS epidemic has been forgotten (El Sadr, Mayer, and Hodder 2010). Researchers have also noted the social gradients discernible in the domestic epidemic, such that HIV/AIDS increasingly affects minority racial/ethnic groups and the poor (Karon et al. 2001; Kraut-Becher et al. 2008; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2006). Although Blacks constitute only 12.8% of the total US population, they comprised 51% of HIV diagnoses from 2001 to 2004 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2006). Further, disparities in mortality due to HIV/AIDS persist, and have increased in the years following the advent of highly active anti-retroviral therapies (HAART) (Lopez et al. 2009; Levine et al. 2007).

The racialisation of the epidemic is mirrored in HIV-related disparities among men who have sex with men (MSM), which some scholars note have been entrenched since the mid-1980s (Millett and Peterson 2007). HIV prevalence among Black MSM in urban settings has been estimated at 46%, and from 2001 to 2006, there were twice as many HIV diagnoses in Black MSM as compared to White MSM (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2005a; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2008). Moreover, national surveillance data show that the proportion of MSM with AIDS within three years of HIV diagnosis was higher in Black MSM as compared to White MSM, and that fewer Black MSM with AIDS were alive three years after receiving an AIDS diagnosis, as compared to White MSM (Hall et al. 2007).

These disparities take place in the context of an epidemic which has transformed over the past two decades. In the post-HAART era, HIV has become deemed a chronic illness, with long-term survival contingent, largely, on access to quality health care (Mitchell and Linsk 2004; Beaudin and Chambre 1996; Simon, Ho and Abdool Karim 2006; Siegel and Lekas 2002). Further, the estimated number of people 50 and older living with HIV/AIDS in the USA has nearly tripled in recent years: 65,655 in 2001 and 156, 511 in 2007 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2005b; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009). Moreover, the proportion of adults 50 and older living with HIV in New York City is currently estimated at nearly 40% (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2010). These transformations and the possibility of extended survival compel us to maximise the potential for long-term survival among marginalised subgroups of those infected, including older Black MSM.

Unfortunately, little is known about the lives of Black MSM living in the USA, and even less is known about older HIV-positive Black MSM. In fact, we are aware of only one published study focusing on older Black seropositive MSM: an intervention study reporting a trend towards reduced risk behaviour among intervention participants (Coleman et al. 2009). More research focuses on younger racial/ethnic minority MSM living with HIV. Qualitative studies with younger Black HIV seropositive MSM suggest that homophobia and financial hardship are frequently encountered social stressors (Han et al. 2010; Miller 2007; Wheeler 2005). Moreover, studies with HIV seropositive Latino and Black MSM suggest that physician mistrust, childhood abuse, and homophobia negatively influence quality of life (Siegel and Raveis 1997; Williams et al. 2004). Other studies with racial/ethnic minority MSM living with HIV have found that community involvement is critical, and that culturally tailored interventions hold much promise in reducing sexual risk behaviours (Ramirez-Valles et al. 2005; Williams et al. 2008).

Although the question of how to address disparities in HIV/AIDS among MSM in the context of the ‘greying’ of the epidemic has not yet been explored, researchers have pointed to the need for a paradigm shift, particularly given evidence that differences in individual risk behaviours do not account for HIV-related disparities (Millett et al. 2007). Some have argued that what is needed is a shift from proximate determinants of risk to social factors, with renewed focus on the role of power, privilege and stigma (Mays, Cochran, and Zamudio 2004; Malebranche et al. 2004; Peterson and Jones 2009). Although little is known about the stigma experiences of older Black MSM living with HIV, research does suggest that HIV-related stigma may be a barrier to the well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS more broadly. For instance, research suggests that stigma is associated with depression and anxiety among people living with HIV (Lee, Kochman and Sikkema 2002). Further, researchers have argued that stigma is key to the social production of health and social inequalities (Stuber, Meyer and Link 2008; Parker and Aggleton 2003; Link and Phelan 2006).

Research also suggests that there may be a strong relationship between stigma and mental and sexual health among MSM. For example, researchers have found that stigma is associated with both psychological distress and sexual risk behaviour in Latino MSM (Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne and Marin, 2001; Rhodes et al. 2010; Nakamura and Zea 2010). However, little is known about how Black MSM experience multiple sources of stigma, and even less is known about what these experiences mean in terms of quality of life among older HIV-positive men. Drawing from studies that illustrate the importance of in-depth approaches to understanding the complex processes involved in living with HIV, we posit that a contextualised understanding of the relationship between stigma and HIV-related disparities in MSM can be best advanced through close engagement with their lived experiences (Barroso and Powell-Cope 2000; Baumgartner 2007; Trainor and Ezer 2000). Life history methods are particularly well-suited for this type of analysis, particularly among members of marginalised groups (Dhunpath 2000; Goodson 2001). In this paper, we use a grounded theory approach (Strauss and Corbin 1998) to analyse the life history narratives of 10 poor gay and bisexual older adult Black men living with HIV in New York City, focusing on what it means to live with the stigmas of race/ethnicity, HIV status, sexual non-normativity, and poverty.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Data were drawn from a larger life history project, the purpose of which was to describe the well-being of older gay and bisexual long-term survivors of HIV and AIDS. Inclusion criteria for the study included: male sex, self-identity as gay or bisexual, self-identity as Black, Latino, or White, age 50 or older, HIV positive for at least 12 years, and residence in New York City. In this analysis, we define poor as being both unemployed and experiencing difficulty meeting the costs of daily living. And, consistent with research on aging and HIV, in this study we define older as 50 years of age or older (Emlet 2006). Participants for the larger study were recruited through the use of small cards posted at community organisations known to serve older gay and bisexual men. The larger study had a sample size of 30, including 10 participants from each of the 3 racial/ethnic groups represented. Findings reported here focus on the 10 Black participants. At the time of data collection, all participants were currently unemployed, and had been living with HIV for on average 18.8 years.

Upon calling to request information about the study, participants were screened for inclusion, and interviews were scheduled among those who met the inclusion criteria. Interviews were conducted in private rooms located at the offices of the Center for HIV Educational Studies and Training (CHEST), an HIV/AIDS research institute with close ties to gay, lesbian, transgendered and bisexual communities in New York City. Consistent with life history methods, which take an ongoing, in-depth approach, all but one of the men in this study were interviewed twice. In total, each life history interview lasted on average 5 hours. Informed consent was obtained as soon as each participant arrived for the interview, and participants were remunerated $50 for their time. Moreover, participants selected their own pseudonyms, which reflect the names used in this publication. Study procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Life history interviews were conducted by the study investigators, Mark B. Padilla and Rahwa Haile, both of whom have extensive experience in qualitative interviewing and data analysis among diverse populations. The interview was designed to obtain life history narratives in roughly chronological order, beginning with discussions of participants’ lives prior to HIV diagnosis, and gradually progressing forward to the present. As is characteristic of life history methods, we emphasised building trust and rapport through taking an explicitly non-judgmental and open-ended participant-centred approach, as well as through actively listening and encouraging respondents to describe at length their memories regarding specified periods of their lives. The interview guide was designed to ensure consistent exploration of particular domains of interest, including: stigma, experiences with clinical providers and social services, social support and coping, and quality of life.

Data Analysis

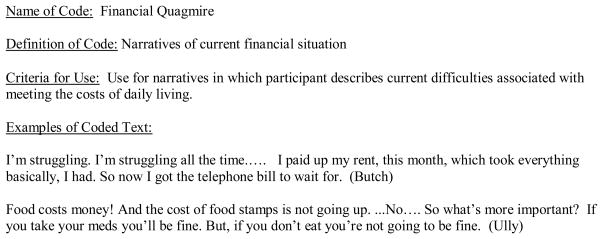

Interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and identifying information was removed from all transcripts. In vivo coding and analytic summaries were conducted with each interview. In vivo coding uses short statements of underlying themes, emphasising participant words and phrases (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Analytic summaries consist of one page overviews of key themes emerging from in vivo codes, and provide a narrative synopsis. Based on these procedures, a provisional codebook was created, consisting of 90 codes, along with their criteria for use.

A small subset of the interviews was then coded by each investigator to ensure viability of the codebook, followed by reflection and discussion. Following this process the codebook was finalised, ultimately consisting of 102 codes, along with their criteria for use. Next, all interviews were re-coded by the first author, although both investigators met frequently to discuss this process. Following coding, data were analysed by examining the full range of responses associated with particular themes of interest, in order to obtain information about experiences and perceptions across the sample. This ‘vertical’ analysis de-contextualises segments of data associated with themes of interest by removing them from the larger transcript for focused analysis, enabling close examination of code-specific responses across the sample (Glaser 2005). Second, along with analytic summaries, subtle variations among participants were situated within the larger context of meaning and experiences of each man. This ‘horizontal’ analysis enabled us to re-situate narratives within the broader context of each man‘s life, in order to develop explanations for variations across the sample (Glaser, 2005).

Results

Our analysis led to the identification of three ways in which participants explained how stigma operates in their lives. First, they described how stigma dehumanises them, as they are routinely treated as just one more body within institutions charged with their care. Secondly, they described the process of knowing your place within institutional and social hierarchies as the mechanism through which they are rendered tolerable. Lastly, participants described the structural dynamics of stigma as pervasive, converging to relegate them to the quagmire of an HIV ghetto.

Just one more body

Participants described stigma as a pervasive force that renders them, as Cee, a 52 year old gay man describes, just one more … body. Participants described this experience as that of being treated in a dehumanised, devalued manner: as a physical presence (a body) that was to be managed and regulated by institutions and their representatives, but ultimately being deemed according to Cee as not that important. In particular, they articulated experiencing themselves as devalued within institutions of supposed care and protection. Thus, institutions mandated by the state to protect them were instead perceived as threatening to their well-being. This led to a sense that there was no recourse, since the social safety net was itself a source of stigmatisation. Cee, for instance, explained his ongoing experiences with substandard medical care as being a direct consequence of the stigma of race and poverty, and the lower value accorded Black people, particularly those who are poor. Originally from the south, Cee explained health care workers’ perspective on poor Black patients as follows:

… when you’re Black and in the south and you don’t have insurance … they don’t care. You just one more Black body that we ain’t have to be concerned with on the planet…. That’s life.1

Cee recounted several experiences in medical care settings in which his well-being was ignored – the most consequential of which was the moment of his HIV diagnosis, which was marked by stigmatising treatment by a health care worker, who informed Cee of his diagnosis by saying:

Your blood has come back…bad …take these, or you’ll be dead in a year ‘ … And I said, Why? He said, Just take ‘em or you’ll be dead. So I said, No, I don‘t think so. And I went out and I got a bottle of gin… and, bout 5 or 10 years later, I was still drinking gin.

Cast outside the border separating valued from devalued bodies, Cee described being treated in an inhumane fashion precisely at the moment in which he most needed support. These types of experiences also characterised his encounters with health care workers in New York, where he characterises physicians as preferring, as he states -- to be in your presence no longer than it takes for them to fill out your paperwork to make sure Medicaid pays them -- a predicament which he personally experienced in being prematurely discharged from a local hospital following a severe psychiatric episode, in which he posed a danger to himself. And, as he described throughout the narrative, his ongoing experiences with marginalising medical care during health crises further impeded his ability to survive with HIV. Cee explained that these events precipitate instances in which people, me included, could be… reckless, and do something really stupid, which he characterised as acts of desperate coping and violent self-abuse.

Participants also described the stigma of non-normative sexuality as meaning that they are devalued within public and social institutions charged with their care and protection. Some participants applied this narrative of institutional stigmatisation to religious institutions. For example Tom, a 55 year old gay man explained that although the Black church has in recent years become more accepting of people living with HIV, those who are gay remain cast outside the church doors. Tom states:

… the church in the African American community does not support being gay…. Some churches are starting now to open their doors to the fact that they have members that are sitting there with HIV… they’re not inviting gays in, but they’re inviting people in….

Similarly, Freire, a 53 year old gay man, described a recent encounter with homophobia at a local college, where he was taking a class. Weeks after having had surgery, he was cornered by fellow male students, who called him a fag and threatened him with violence. Although he was able to leave the incident physically unharmed, Freire was terrified to return to college, and promptly alerted the University and local police authorities, whom he expected to investigate. Instead, he explained that absolutely nothing was done, nothing. As a consequence of the homophobic threat and the failure of authorities to investigate, Freire described experiencing severe anxiety attacks. Desperate to reach some sort of resolution, he independently enlisted the help of a legal aid society, and continues to await a sufficient institutional response.

In addition to feeling dehumanised, Jacob, a 53 year old bisexual man described being treated as though his presence poses a threat to public safety; as though he inherently constitutes an inherent threat to public order, and thus merits heightened surveillance. Jacob spoke at length about his fear of police harassment in his neighbourhood. He explained:

I don’t live in a crime-ridden neighbourhood, but the police, you couldn’t even go outside, and you can’t even go outside up there where I live… I don’t want to be coming out of the store, and they decide to target me.

From Jacob’s perspective, the streets were understood as a dangerous space, not because of civilian crime, but because of the learned expectation that he will be harassed by the police. Consistent with Manalanasan’s (2005) ethnographic research, which documents heightened police regulation of LGBT people of colour during the post 9/11 era, Jacob explained observing extreme police regulation in recent years, which has had the effect not of making him feel safer, but of making him fear leaving his home. Jacob recognised the need and value of law enforcement, but expressed fear of law enforcement officers, expressing little confidence that the gaze of the state upon Black bodies such as his own is protective.

Knowing your place

Stigmatisation was manifest in what some men described as knowing your place, that is, the process whereby they are reconfigured as tolerable by submitting to existing social and institutional imperatives. Because entry into the public sphere is understood as requiring the acceptance of a subservient social position, social interaction necessitated the forced internalisation of their place in the established order. For example, Ully, a 61 year old gay man described Black people’s belonging within the larger gay community as dependent on their willingness to passively accept racial hierarchies, within which the needs and perspectives of Blacks are sometimes insufficiently valued. In describing his reluctance to pursue gay political causes, Ully stated:

I think for African Americans, it’s hard to feel like you make a difference…. There’s a hierarchy in the gay community… we’re the lowest on the totem pole…. You have to know your place.

Poverty functioned as another social axis that required participants to know their place. For example, in describing how the stigma of poverty operates in mixed class settings, Sho, a 58 year old bisexual man, described experiencing a policing of borders that keeps the poor outside of particular social spaces. Although he described being permitted to associate with those more affluent than him, Sho explained that this association is contingent on his ability to understand, internalise and abide by the social and symbolic borders separating the poor from the non-poor. He described this process as follows:

I’ve met Black upper upper, and they’re the same way as the White upper upper…: Stay over there. You can sit and eat, but don’t eat too much. ‘You have to always know … your place: You’re not one of us…. We don’t know you, and you don’t know us. You know of us’

Participants also described the need to demonstrate knowledge of their place in relationship to the stigma of sexual non-normativity. One way in which they described enacting the mandate to know their place is through adopting the stigma management technique of sexual invisibility. Given that they are neither accepted nor assured safety --particularly during moments of gender nonconformity or sexual candour-- participants described needing to tone down these qualities. For example, Chris, a 50 year old bisexual man, recounted observing an act of anti-gay harassment on the subway. He recalled that a man wearing the rainbow pride colours was riding on the train, and that another subway patron verbally threatened him, shouting “You want a body slam looking at me like that?” Later, using the incident as personally instructive, Chris rationalised the verbal attack as an expected consequence of the victim‘s brazen declaration of his sexual identity, and matter-of-factly stated that although gay bashing may be less of an issue in the contemporary era than in previous eras, “They still doing it, so it doesn‘t give him license you know, to put himself out there…. That’s what I have to remember”. Knowing and demonstrating knowledge of your place in relation to race, class, and sexuality was thus experienced as a normative social code internalised and reproduced as a matter of basic survival.

In other instances, participants critiqued other sexual minorities for subverting this social mandate. For example, in describing younger gay men, Butch, a 63 year old bisexual man, argued that the propensity of some gay youth to challenge norms of gender presentation threatens the already precarious position of gays:

It’s the young queens … that make… the bad stigma for gay people…. They’re just out of control.... they wear scare drags… you know, they have on…girl pants, maybe a man’s hat, with hair… they looking like a freak… and…that makes people look, that makes straight guys make comments.

In this way, Butch critiques young gays’ subversion of gender norms and – similar to research findings with Black MSM living in London—partially displaces blame for the stigma of sexual non-normativity onto younger gay gender non-conformists (Anderson et al. 2009).

Stuck in the Quagmire of an HIV Ghetto

Just as participants described being compelled to understand, internalise and comply with their place within larger social and institutional hierarchies, they also described the ways in which the structural dynamics of stigma had physically and emotionally immobilising consequences. Although participants described their desire for economic autonomy, they were without jobs and in substandard living conditions due to structural constraints on their ability to simultaneously work and receive state aid to help meet the costs of medical care. Further, their position as beneficiaries within the institutional circuit of aid left them highly vulnerable, and with little social power to influence the quality and reliability of their own care. Ully described this state of existence as that of being stuck in the quagmire of an HIV ghetto:

Living below the poverty line … down in a quagmire… in this ghetto where everybody lives that is HIV positive… in this place filled with misery and despair and longing, and no way out.

Some participants described this experience in relationship to their desire for employment. For example, Yellowdaddy, a 50 year old bisexual man, describes a link between his health status and his employment status, stating that to work makes him feel like he is “coming back to myself and that when I was working I was undetectable [in viral load] and I was taking them [medications] faithfully”. Moreover, although participants desired the autonomy and health-promoting benefits associated with working, many feared actively pursuing employment, given the dire consequences it could have for their ability to access life-sustaining medications. Participants described feeling stuck between longing for the independence that work provides and the reality of their dependence on social service benefits to meet their medical expenses. Butch summarised this predicament as follows:

I don’t buy the newspaper anymore. You know…little things that you do when you’re working…If they…could find… me a job, and let me keep my Medicaid…I would work. You know…for that medication… a job is not gonna …do it.

Participants’ fears about the consequences of securing employment were typically based in their own past experiences. For example, although over his life he has derived a great deal of meaning from his work as a nurse, Tim a 61 year old bisexual man, explained that he no longer pursues paid work because of the potentially disastrous consequences. Having been perceived to have exceeded the income SSI (Supplemental Security Income) beneficiaries are permitted to earn, he was nearly evicted from his apartment after securing paid employment:

The last time I went back to work, I almost got thrown out of my own apartment because of income problems… excessive income. I had to go to court and fight a long court battle.

Aware of the potential consequences of exceeding permissible income levels, some participants described explicitly consulting with social welfare personnel in order to ensure that they were within the permitted income boundaries. However, some described severe outcomes even in these circumstances, which caused them to further fear working, despite longing for the confidence and integration that work provides. For example, keenly aware of the grave financial complications which can follow pursuing paid work, Ully described consulting with Social Security personnel before beginning part-time work as a drug counsellor, to ensure that he would be compliant with the existing rules. However, decades later, Ully still experienced the economic repercussions of the decision to return to work. He described the situation and its implications as follows.

I made the decision to go back to work based on the information Social Security provided for me. … I got a letter in December of the next year from Social Security saying, You don’t get a check this month because you owe us $16,000. ‘… They said that I had been overpaid because I was making more…. To this day, they’re taking $230 off my Social Security check…. So, you suffer, you suffer, you suffer. You’re still in the quagmire of that HIV ghetto. Once you’re down they gonna kick you, honey.

Although he tried to fight the allegation of excessive income through presenting documentation that he was consistently within the permissible income levels, as a recipient of aid, Ully was ultimately constrained by his lack of power to navigate the social welfare system. Other participants described a similar sense of powerlessness. Although grateful for the medical care and financial and housing assistance that they receive, some participants described the provision of such care as sometimes unpredictable, even during moments of severe health crisis. For example, Freire described a moment during which his health benefits were intermittently severed during his battle with brain cancer:

When I was going through radiation and chemotherapy and I was on public assistance… they kept cutting off my fuckin Medicaid…they fuck with you… it stresses you out … it‘s killing you.

Freire describes the health consequences of this process as direct and irreversible. Added to the intense physical and emotional stress associated with struggling to physically survive HIV and its associated co-morbidities, he states that these instances of structural disregard can slowly kill you. And, as he later suggested, repeated exposure to these highly stressful experiences can “accumulate”, causing him and intimate others to “lose T-cells”2; indicating his perception of the gradual physical erosion of their ability to continue to survive, over time.

Discussion

In response to disparities in HIV/AIDS borne by Black MSM, recent research has begun to examine whether stigma and discrimination may play a role. Important advances have been made in this body of work. For example, some researchers have found high levels of homophobic attitudes within Black communities, and others have found that Black MSM may frequently encounter racist attitudes within LGBT communities (Stokes, Vanable and McKirnan 1996; Battle et al. 2002). These forms of stigma may hinder the use of HIV testing services and prevention programs (Brooks et al. 2005). However, a limitation of these studies is their tendency to focus on individualised acts of stigmatisation and discrimination only as they occur within Black and LGBT communities (Haile 2009).

In contrast, participants in this study described stigma as an intractable social force that has impeded their ability to survive with HIV. Rather than revolving around interpersonal experiences of stigma that take place within Black and LGBT communities, these men’s narratives centred on the ways in which stigma manifests in the broader structures that organise public, institutional, and social life. In order to access the services they needed to survive, these men had to become subservient to the state and welfare services, but in doing so they were exposed to compromising social and economic dangers that they perceived as reducing their life chances. Participants described being treated as just one more body within their interactions with medical care providers and law enforcement authorities, which dehumanised them in the process of caring for themselves, and depleted them of the emotional resources they could call upon to do so. Further, they described the need to diminish their personhood by tolerating their own marginal position within broader social and institutional hierarchies by knowing their place. Finally, they described the ways in which these dynamics converged to relegate them to the quagmire of an HIV ghetto dependent on the precarious provision of social welfare, and constrained in their ability to influence its quality and reliability.

The social settings and public spaces within which participants reported exposure to stigma were multiple and ubiquitous, including the general urban and social spaces of their neighbourhoods, subways, churches, educational settings, clinics, hospitals, and social service offices. The perpetrators of stigma were similarly diffuse and omnipresent, often including public workers like police officers, health providers, and social service personnel who are charged with caring for people living with HIV. The ubiquity of contexts within which stigmatisation takes place suggests the existence of an underlying, antecedent social structure that extends beyond the borders of the Black and LGBT communities that are typically the focus of discussions of stigma among Black MSM. Our study therefore contributes to the conceptualisation of the stigma experiences of older Black MSM with HIV/AIDS as multiple and pervasive potentially illustrative of a general structure of systematic disadvantage that has a much greater impact on their overall health and well-being than current frameworks imply. These findings are consistent with Foucauldian theories of biopower, which have reframed discussions of social marginalisation by describing the ways that modern nation-states create institutions that effectively function to regulate and discipline bodies and practices in the context of care (Foucault 1990). The men in this study expressed a pervasive and all-consuming sense of institutionalised oppression that is remarkably akin to Foucault’s (1990) work, suggesting that the exercise of biopower has a palpable impact on their experience as subjects of the state.

Limitations

Despite the eloquence with which our participants described the role of stigma in their lives, this study has important limitations. First, our small non-probability sample consisted of only ten men, some of whom migrated to New York from other regions of the United States, where experiences of stigma may diverge from those experienced in New York City. Thus, we cannot assume generalisability of these findings. Future studies should determine whether the pervasive structural experiences of stigma we document are applicable to a broader sample. Second, as with all research based on self-reported data, it is possible that some of our interviews could have been influenced by social desirability bias. For instance, participants could have minimised the ways in which social support networks may help them to mitigate the consequences of stigma. Third, while our study focused specifically on men who identified as gay or bisexual, some Black men who have sex with men may not identify with these labels. Further, we recruited participants from organisations known to serve gay and bisexual men. We therefore cannot determine whether or to what degree the experiences described here are reflective of those among a broader population of Black MSM. It is possible that our participants were more comfortable or aware of their non-normative sexual desires and behaviours than is reflective of the broader population of Black MSM, and therefore experienced different levels or types of stigma as a result. Future studies should aim to understand the nature, process, and health impacts of stigma and discrimination among the broader population of Black MSM, including men who do not identify as gay or bisexual.

Implications

Despite its limitations, this study has important implications. Men in this study narrated a clear sense of themselves as devalued not simply within Black or LGBT communities, but also in relationship to the state and its agents. Thus, consistent with human rights approaches to stigma, these narratives suggest that structural factors may facilitate the enactment of stigmatisation and discrimination at the individual level (Farmer 2005; Parker and Aggleton 2003). Efforts to reduce the pervasive effects of stigma may be strengthened by the development and support of policies that prohibit discrimination: for example, a federal law prohibiting employment discrimination based on sexual orientation in the United States. In support of this approach, recent research suggests that living in US states that protect LGBTs from discrimination may have protective effects for mental health (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes and Hasin 2009). Additionally, a structural approach emphasises that efforts to reduce the pervasive effects of stigma on health may also be strengthened by the promotion of social or structural changes based on the human right to dignified and humane treatment. Such interventions should consider health in the broadest sense, including the need for economic and social integration and dignity, not simply the provision of medical care or marginal financial support for the unemployed. Such individual services may insufficiently promote health and well-being if they are divorced from the structural determinants of stigmatisation and discrimination. Moreover, as others have noted, there is insufficient research on the intersection between structural issues and HIV prevention in Black MSM (Peterson and Jones 2009). Thus, future studies must aim to systematically examine the lived experiences of a broad range of Black MSM and the specific ways in which structural and interpersonal forms of stigma and discrimination intersect to shape disparities in HIV-related morbidity and mortality.

Figure 1.

Example of code and coded Text

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, full sample of Black gay and bisexual men (n=10)

| Demographic characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Variables | Mean | SD |

| Age | 55.6 | 3.8 |

| Years HIV- Positive | 18.8 | 3.3 |

| Categorical Variables | n | % |

| Sexual Identity | ||

| Gay | 5 | 50% |

| Bisexual | 5 | 50% |

| Education | ||

| High School or Less | 3 | 30% |

| Some College | 4 | 40% |

| College Degree | 2 | 20% |

| Some Postgraduate | 1 | 10% |

| Current Employment Status | ||

| Unemployed | 10 | 100% |

Footnotes

All italics reflect participant emphasis.

T-cells refer to CD4 cells, which are a type of White blood cell. Among people living with HIV the number of T-cells is often used as a measure of immune functioning.

References

- Anderson M, Elam G, Gerver S, Solarin I, Fenton K, Easterbrook P. Liminal identities: Caribbean men who have sex with men in London, UK. Culture, Health & Sexuality: An International Journal for Research, Intervention and Care. 2009;11:315–30. doi: 10.1080/13691050802702433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso J, Powell-Cope GM. Metasynthesis of qualitative research on living with HIV infection. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10:340–53. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle J, Cohen C, Warren D, Fergerson G, Audam S. Say it loud: I’m Black and I’m proud, Black pride survey 2000. New York: The Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner LM. The incorporation of the HIV/AIDS identity into the self over time. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:919–31. doi: 10.1177/1049732307305881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudin CL, Chambre SM. HIV/AIDS as a chronic disease: Emergence from the plague model. American Behavioral Scientist. 1996;39:684–706. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RA, Etzel MA, Hinojos E, Henry CL, Perez M. Preventing HIV among Latino and African American gay and bisexual men in a context of HIV- related stigma, discrimination, and homophobia: Perspectives of providers. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2005;19:737–44. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevalence, unrecognised infection, and HIV testing among men who have sex with men -- five U.S. cities, June 2004–April 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2005a;54:597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV and AIDS in the United States, 2004. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 2005b;14:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States, by race/ethnicity, 2000–2004. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 2006;12:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in HIV/AIDS diagnoses among men who have sex with men –33 states, 2001–2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57:681–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2007. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 2009;19:1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman CL, Jemmott J, Jemmott B, Strumpf N, Ratcliffe S. Development of an HIV risk reduction intervention for older seropositive African American men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23:647–55. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhunpath R. Life history methodology: “Narradigm” regained. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 2000;13:543–51. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:927–32. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr WM, Mayer KH, Hodder SL. AIDS in America -- forgotten but not gone. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:967–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA. You’re awfully old to have this disease: Experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. The Gerontologist. 2006;46:781–90. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P. Pathologies of power: Health, human rights, and the new war on the poor. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. An introduction. I. New York: Vintage Books; 1990. The history of sexuality. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding. Mill Valley: Sociology Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson I. The story of life history: Origins of the life history method in sociology. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2001;1:129–42. [Google Scholar]

- Haile R. PhD diss. University of Michigan; 2009. Social stigma and HIV/AIDS in Black MSM. [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Byers RH, Ling Q, Espinoza L. Racial/ethnic and age disparities in HIV prevalence and disease progression among men who have sex with men in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1060–66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Lauby J, Bond L, LaPollo A, Rutledge S. Magic Johnson doesn’t worry about how to pay for medicine: Experiences of Black men who have sex with men living with HIV. Culture, Health & Sexuality: An International Journal for Research, Intervention and Care. 2010;12:387–99. doi: 10.1080/13691050903549030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2275–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karon JM, Fleming PL, Steketee RW, De Cock KM. HIV in the United States at the turn of the century: An epidemic in transition. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1060–68. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut-Becher J, Eisenberg M, Voytek C, Brown T, Metzger D, Aral S. Examining racial disparities in HIV: Lessons from sexually transmitted infections research. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;(Suppl no 1) doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605b95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RS, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Internalized stigma among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:309–19. [Google Scholar]

- Levine RS, Briggs N, Kilbourne BS, King WD, Fry-Johnson Y, Baltrus PT, Husaini BA, Rust GS. Black White mortality from HIV in the United States before and after introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy in 1996. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1884–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. The Lancet. 2006;367:528–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez G, Simone B, Madariaga MG, Anderson J, Swindells S. Impact of race/ethnicity on survival among HIV-infected patients in care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20:982–95. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Peterson JL, Fullilove RE, Stackhouse RW. Race and sexual identity: Perceptions about medical culture and healthcare among Black men who have sex with men. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004;96:97–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manalansan MF. Race, violence, and neoliberal spatial politics in the global city. Social Text. 2005;23:141–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, Zamudio A. HIV prevention research: Are we meeting the needs of African American men who have sex with men? Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30:78–105. doi: 10.1177/0095798403260265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RL. Legacy denied: African American gay men, AIDS, and the Black church. Social Work. 2007;52:51–61. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among Black and White men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21:2083–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL. The known hidden epidemic of HIV/AIDS among Black men who have sex with men in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;(Suppl no 1) doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CG, Linsk NL. A multidimensional conceptual framework for understanding HIV/AIDS as a chronic long-term illness. Social Work. 2004;49:469–77. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Zea MC. Experiences of homonegativity and sexual risk behaviour in a sample of Latino gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality: An International Journal for Research, Intervention and Care. 2010;12:73–85. doi: 10.1080/13691050903089961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV Epidemiology & Field Services Semiannual Report. 2010;5:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Parker RG, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Jones KT. HIV prevention for Black men who have sex with men in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:976–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J, Fergus S, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Zea MC. Confronting stigma: Community involvement and psychological well-being among HIV-positive Latino gay men. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27:101–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Aronson RE, Bloom FR, Felizzola J, Wolfson M, Vissman AT, Alonzo J, Allen AB, Montaño J, Mcguire J. Latino men who have sex with men and HIV in the rural south-eastern USA: Findings from ethnographic in-depth interviews. Culture, Health & Sexuality: An International Journal for Research, Intervention and Care. 2010;12:797–812. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.492432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Lekas HM. AIDS as a chronic illness: Psychosocial implications. AIDS. 2002;(Suppl no. 4) doi: 10.1097/00002030-200216004-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Raveis V. Perceptions of access to HIV-related information, care, and services among infected minority men. Qualitative Health Research. 1997;7:9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Simon V, Ho D, Abdool Karim Q. HIV/AIDS epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. The Lancet. 2006;368:489–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69157-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, Vanable PA, McKirnan DJ. Ethnic differences in sexual behavior, condom use, and psychosocial variables among Black and White men who have sex with men. The Journal of Sex Research. 1996;33:373–81. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stuber J, Meyer IH, Link BG. Stigma, prejudice, discrimination and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:351–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor A, Ezer H. Rebuilding life: The experience of living with AIDS after facing imminent death. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10:646–60. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DP. Working with positive men: HIV prevention with Black men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17:102–15. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.2.102.58693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Wyatt G, Rivkin I, Ramamurthi H, Li X, Lieu H. Risk reduction for HIV-positive African American and Latino men with histories of childhood sexual abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:763–72. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9366-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JK, Wyatt GE, Resell J, Peterson JL, Asuan-O’Brien A. Psychosocial issues among gay- and non-gay-identifying HIV-seropositive African American and Latino MSM. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:268–86. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]