Abstract

Background

Kinesins constitute a large superfamily of motor proteins in eukaryotic cells. They perform diverse tasks such as vesicle and organelle transport and chromosomal segregation in a microtubule- and ATP-dependent manner. In recent years, the genomes of a number of eukaryotic organisms have been completely sequenced. Subsequent studies revealed and classified the full set of members of the kinesin superfamily expressed by these organisms. For Dictyostelium discoideum, only five kinesin superfamily proteins (Kif's) have already been reported.

Results

Here, we report the identification of thirteen kinesin genes exploiting the information from the raw shotgun reads of the Dictyostelium discoideum genome project. A phylogenetic tree of 390 kinesin motor domain sequences was built, grouping the Dictyostelium kinesins into nine subfamilies. According to known cellular functions or strong homologies to kinesins of other organisms, four of the Dictyostelium kinesins are involved in organelle transport, six are implicated in cell division processes, two are predicted to perform multiple functions, and one kinesin may be the founder of a new subclass.

Conclusion

This analysis of the Dictyostelium genome led to the identification of eight new kinesin motor proteins. According to an exhaustive phylogenetic comparison, Dictyostelium contains the same subset of kinesins that higher eukaryotes need to perform mitosis. Some of the kinesins are implicated in intracellular traffic and a small number have unpredictable functions.

Background

Eukaryotic cells express three types of motor proteins: myosins, kinesins and dyneins [1]. Each constitutes a large superfamily based on the highly conserved motor domain [2-4]. All motors have in common that they use the energy derived by the hydrolysis of ATP to produce mechanical force. While myosins move on actin filaments, kinesins and dyneins are responsible for the retrograde and anterograde transport along microtubule tracks. The first kinesin was isolated from squid giant axons as a protein responsible for fast axonal transport [5,6]. This conventional kinesin (KHC) was shown to be a tetramer including two heavy and two light chains. The heavy chain consists of an N-terminal motor domain with microtubule affinity and ATPase activity followed by an extended coiled-coil region containing the light chain binding site [7] and a C-terminal domain that binds to the cargos. Like KHC, most kinesins have their motor domains at the N-terminus. However, in some kinesins, the motor domain is located in the centre of the molecule and a few others have C-terminal motor domains. In general, the position of the motor domain determines the directionality of transport: N-terminal kinesins move to the plus end and C-terminal kinesins to the minus end of microtubules [8]. Kinesins with central motor domains do not generate movement but function as microtubule depolymerases [9].

Based on phylogenetic analysis, kinesins were grouped into nine [3] or, more recently, thirteen subfamilies [10]. Higher eukaryotes share a common subset of ten subfamilies. Additionally, there are some kingdom specific kinesin subfamilies. Together with the subfamilies, the cellular functions of the kinesins seem to have segregated, although there are some exceptions. Three subfamilies are implicated in organelle transport: KHC, Unc104/Kif1, and Osm3 kinesins. KHC subfamily members have been reported to transport numerous membrane cargoes such as, for example, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticula and lysosomes [11]. Lower eukaryotic Unc104 motors have more general roles in membrane trafficking, while their metazoan orthologs specialize in transporting synaptic vesicle precursors in the nervous system [12]. Osm3 kinesins are heterotrimeric and primarily involved in "intraflagellar transport" [1] but are also involved in other tasks, including the transport of vesicular cargoes in neurons [13].

The six subfamilies solely attributed to mitotic functions are the BimC/Eg5, NCD/Kar3, MKLP1, MCAK/Kif2, Kip3 and CENP-E motors. All BimC motors examined to date have been found to be located on the microtubules between spindle poles [14,15] and to form bipolar tetramers [16]. They are supposed to cross-link antiparallel microtubules in the spindle midzone [16] and to slide them past one another to separate poles. To organise the spindle microtubules, BimC kinesins work together with C-terminal motors of the NCD/Kar3 subfamily [17]. Kar3 and NCD, the most extensively analysed C-kinesins, can both bind microtubules with their N-terminal tails [18] and therefore cross-link and slide microtubules by anchoring their tails to one microtubule, while generating force with their motor domains against adjacent microtubules. MKLP1 kinesins are involved in mitosis associated with the spindle midzone during anaphase and concentrating to a midbody matrix during cytokinesis [19]. MCAK/Kif2 kinesins are reported to destabilize microtubules [20] and associate to mitotic centromers [21]. The attachment of MCAK to the centromer is mediated via non-motor domains [22], while the motor domain is responsible for microtubule depolymerisation [20,23]. Vertebrate members of the CENP-E subfamily have been shown to bind to kinetochores during mitosis [24] and are involved in chromosome segregation. In interphase cells, Kip3 from S. cerevisae localizes to cytoplasmic microtubules, during mitosis it is most concentrated along the nuclear spindle, and late in anaphase it is preferentially found in the spindle midzone [25,26].

Compared to the vast amount of data describing the structures, functions and localisations of Dictyostelium myosins [27,28], there are so far only a few investigations of Dictyostelium kinesins. Already in the early days of kinesin research the first Dictyostelium kinesin was isolated from cell lysates as a 105 kDa protein, based on its nucleotide-dependent binding to microtubules [29]. About ten years later, a PCR-based approach resulted in the full-length sequence of one kinesin (K7) and short fragments of further kinesins (K3, K4, K6, and K8) [30]. K7 was also analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy and shown to localise to a membranous perinuclear structure. Using the video microscopic observation of organelle transport in vitro as an assay, two further kinesins of 170 and 245 kDa were isolated [31]. The 245 kDa kinesin was found to be an Unc104/Kif1A homologue responsible for about 60 % of organelle movement. The third kinesin sequence (K2) revealed a C-terminal type kinesin related to the NCD/Kar3 subfamily. K2 localised as GFP fusion to the nuclei of cells at the interphase and to mitotic spindles during mitosis [32]. Two further sequences were obtained as a result of the assembly of the genomic sequences of chromosome 2 [33].

The genome of Dictyostelium discoideum is covered now with shotgun reads to a depth of 6 to 8 [34]. Here, we have obtained the full set of kinesin superfamily proteins by homology searches for the motor domain. In addition to the five known kinesins, we identified eight new superfamily members. The sequences of the motor domains were aligned with those of 377 kinesins from 50 species found in the databases and phylogenetically analysed. The Dictyostelium kinesins group into nine subfamilies, one of the kinesins constituting the founder of a new class.

Results

Identification and nomenclature

Thirteen kinesins were identified in the Dictyostelium genome, based on the sequence homology of the kinesin motor domain, and their full-length sequences were assembled (Fig. 1, Table 1). Five of the sequences have already been published [30-33] as well as fragments of DdKif3, DdKif4, DdKif6, and DdKif8 [30]. Since genes belonging to the same family should be designated by using the same acronym, we decided to give all the kinesins the acronym Kif followed by a number. Following the Dictyostelium genetic convention, which is intended to be conform with the conventions derived from Demerec et al. [35], the Dictyostelium kinesins are given a locus descriptor consisting of three italic letters, followed by a capital italicised letter to distinguish genes. In an early analysis of Dictyostelium genes [36], the kinesin genes were assigned the acronym ksn. However, this acronym ksn is not used for kinesin proteins of any other organism and it does not appear in the common databases (for example GeneBank or Trembl). We chose Kif because this name is in accordance with the nomenclature of human and mouse kinesins. Other acronyms like Klp (for kinesin-like protein) or Krp (for kinesin related protein) are not as widely used and have misleading implications. The established numbering was retained and the newly discovered kinesins added in random order.

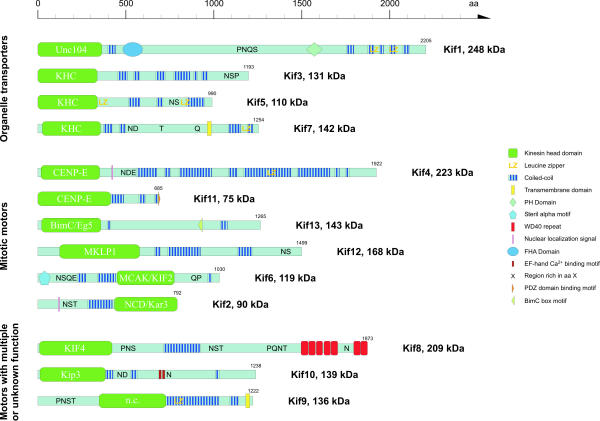

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the domain structures of Dictyostelium kinesins. The class designation is given in the motor domain of the respective kinesin. A colour key to the domain names and symbols is given on the right. Some of the names are abbreviated: PH, pleckstrin homology; FHA, forkhead homology associated; PDZ, a domain with potential for targeting membrane sites.

Table 1.

Members of the kinesin gene superfamily in D. discoideum.

| Protein name | Old name | Size in amino acids | Class | Family | No. of introns | Chromosome | Gene accession | Protein accession | dictyBaseID | Reference |

| Kif1 | Unc104 | 2205 | N-3 | Unc104 | 2 | * | AF245277 | AAF63384.1 | 0001378 | [31] |

| Kif2 | K2 | 792 | C-1 | NCD/Kar3 | 1 | 1 | AB102779 | BAC56911.1 | 0191126 | [32] |

| Kif3 | K3/KHC1 | 1193 | N-1 | KHC | 2 | 3 | AY484460 | AY484460_1 | 0003767 | |

| Kif4 | K4 | 1922 | N-7 | CENP-E | 1 | 4 | AB102780 | BAC56912.1 | 0003768 | |

| Kif5 | KHC2 | 981 | N-1 | KHC | 3 | 2 | AC115592.2 | AAM09366 | 0185205 | [33] |

| Kif6 | K6 | 1030 | M-1 | MCAK/KIF2 | 2 | 1 | AY484461 | AY484461_1 | 0001749 | |

| Kif7 | K7 | 1254 | N-1 | KHC | 3 | 3 | AAB07748 | U41289 | 0001753 | [30] |

| Kif8 | K8 | 1873 | N-5 | KIF4 | 2 | 4 | AY484462 | AY484462_1 | 0001748 | |

| Kif9 | 1222 | novel class | 1 | 2 | AC116957.2 | AAO52566 | 0185204 | [33] | ||

| Kif10 | 1238 | N-8 | Kip3 | 0 | 6 | AY484463 | AY484463_1 | |||

| Kif11 | 685 | N-7 | CENP-E | 0 | * | AY484464 | AY484464_1 | |||

| Kif12 | 1499 | N-8 | MKLP1 | 2 | 1 | AY484465 | AY484465_1 | |||

| Kif13 | 1265 | N-2 | BimC/Eg5 | 3 | 6 | AY484466 | AY484466_1 |

* = chromosome 4 or 5

Phylogenetic analysis and classification

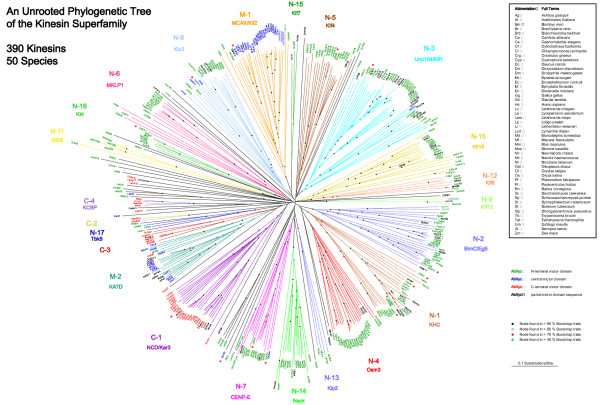

A phylogenetic tree of the motor domains of the Dictyostelium kinesins together with 377 kinesin motor domain sequences from 50 species found in the public databases was created (Fig. 2, supplementary data [see Additional file 1]). The tree is in basic agreement with the phylogenetic results of earlier investigations that, however, only included 146 kinesins in the most extensive analysis [3]. The kinesin superfamily comprises 17 subfamilies of N-terminal motors, two subfamilies of kinesins with central motor domains, and four subfamilies with C-terminal kinesins. Subfamilies were only assigned when kinesins of different organisms contribute. The new subfamilies were designated obeying the more general nomenclature of Miki et al. [10] (N-1 to N-17, M-1 and M-2, C-1 to C-4) as well as following the old convention that new classes should be named after the first member discovered. According to this phylogenetic tree, twelve of the Dictyostelium kinesins group into nine different subfamilies, only DdKif9 might be an orphan or the founder of a new class. Based on the position of their motor domains, two of the kinesins (DdKif6 and DdKif9) are of the middle motor domain type, one (DdKif2) has the motor domain at the C-terminus and the remaining kinesins have N-terminal motor domains.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of 390 kinesins from 50 species found in the common databases. Amino acid sequences of the motor domains were aligned by using maximum parsimony. Sequences used for alignment are available as supplemental material.

Organelle transporters

Based on the phylogenetic tree, four Dictyostelium kinesins group to the Unc104/Kif1 (DdKif1) and KHC (DdKif3, DdKif5, DdKif7) subfamilies that are implicated in organelle transport (Figs 1, 2). Two of the KHC subfamily members are new.

DdKif3 (KHC subfamily)

This kinesin contains an N-terminal motor domain followed by a 30 aa linker consisting of only glycine and serine residues. The linker is connected to a long α-helical domain composed of several predicted coiled-coil regions. The C-terminus (aa ~980–1193) is extremely rich in asparagine, proline and serine residues. It is predicted not to contain any secondary structural elements, except for loops, and might therefore only fold in the presence of specific interacting proteins or membranes. The small peptide sequence obtained from tryptic digest of a 170 kDa kinesin that is able to reconstitute plus-end directed membrane transport [31] is identical to DdKif3. Interestingly, the sizes from SDS gel electrophoresis and weight calculation (131 kDa) are quite different.

DdKif5 (KHC subfamily)

Based on phylogenetic appearance, protein length and domain organisation, DdKif5 is the most similar Dictyostelium kinesin to human conventional kinesin. Neck and tail domains are composed of long α-helical stretches, which are predicted to form interrupted coiled-coils. The probability of building dimers or higher oligomers is enhanced by two leucine zippers (at aa ~350 and ~810). The respective tail sections of the Dictyostelium KHC subfamily kinesins do not show a strong homology to the KLC binding site (amino acid residues 770–810 [7]) of human KHC. This heptad-repeat region is highly conserved between mammalian and invertebrate species and most likely forms an α-helical coiled-coil interaction with a corresponding heptad-repeat region of KLC. Nonetheless, DdKif5 is the Dictyostelium kinesin with the highest similarity in this region and therefore the most likely candidate for binding of possible Dictyostelium kinesin light chains.

Mitotic motors

Dictyostelium contains six kinesin motor proteins belonging to subgroups predicted to function exclusively during mitosis (Figs 1, 2). Two of them belong to the CENP-E subfamily (DdKif4, DdKif11) and one each to the BimC/Eg5 (DdKif13), MKLP1 (DdKif12), MCAK/Kif2 (DdKif6) and NCD/Kar3 (DdKif2) subfamilies. The C-terminal kinesin Kif2 has already been described [32].

DdKif4 (CENP-E subfamily)

Phylogenetically, Kif4 groups to the mammalian and metazoan CENP-E kinesins. Those motors belong to the longest of all kinesins and have tails of about 2000 aa forming coiled-coil structures. In a similar way, DdKif4 contains a tail of long, interrupted coiled-coil regions. In contrast to the other CENP-E kinesins, Kif4 has a putative nuclear localisation signal C-terminal to its motor domain.

DdKif11 (CENP-E subfamily)

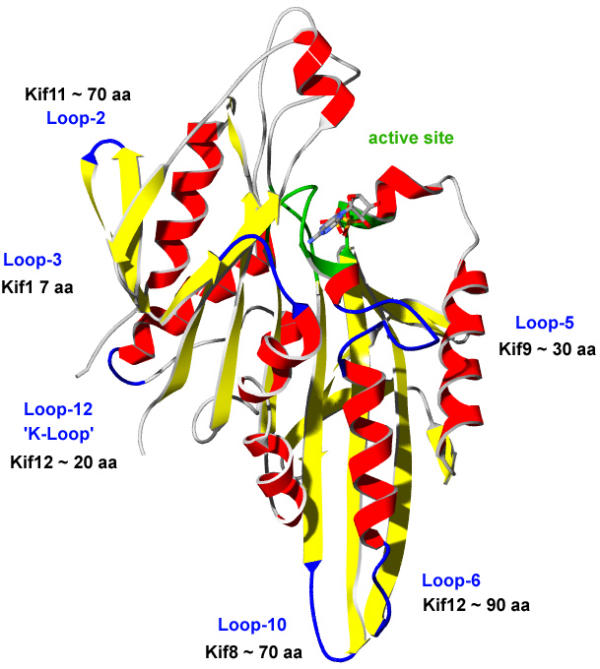

DdKif11 is the shortest of the Dictyostelium kinesins and groups to the plant branch of the CENP-E subfamily. The primary sequence of the motor domain shows an elongated loop-2 (L2) containing five consecutive LKTP motifs (Fig. 3). The non-motor part of the protein is mostly α-helical and predicted to form coiled-coils. The protein sequence ends with amino acid residues EVML. This motif is implicated in binding of PDZ domains (the name PDZ derives from the first three proteins in which these domains were identified: PSD-95, DLG, and ZO-1 [37]). PDZ domains play important roles in the transport, localization and assembly of supramolecular signalling complexes [39].

Figure 3.

Structure of the motor domain of human Kif5B [78] highlighting loops for which some of the Dictyostelium kinesins have long insertions. The approximate lengths of the insertions are given.

DdKif13 (BimC/Eg5 subfamily)

Overall, Kif13 has a similar domain organisation to other members of this subfamily. As most members of the BimC/Eg5 family, it shares several invariant amino acids surrounding a conserved p34cdc2 kinase consensus phosphorylation site (S/TPxK/R). This conserved sequence has been termed the BimC box motif [40]. Mutation of threonine to alanine in this motif has been shown to prevent their association with the mitotic spindle for both Xenopus and human Eg5 [41,42].

DdKif6 (MCAK/Kif2 subfamily)

At the N-terminus, DdKif6 contains a sterile alpha motif (SAM) domain [43]. This domain is a putative protein-protein interaction module that is present in a wide variety of proteins involved in many biological processes [44]. SAM domains do not form homo-oligomers in solution [45,46], although homodimers of SAM domains of different proteins have been found in crystal structures [47]. Instead, SAM domains hetero-oligomerize either by interacting with SAM domains of other proteins [44] or with other protein modules like the Src homology 2 (SH2) domains [48]. Following the SAM domain, DdKif6 contains long stretches of consecutive asparagine, serine, glutamine and glutamic acid residues. The regions neighbouring the central motor domain are mostly α-helical and are partly predicted to form coiled-coils.

DdKif12 (MKLP1 subfamily)

DdKif12's motor domain contains a long N-terminal extension (~120 residues) and an extremely long loop-6 (L6) that constitutes the succession of the P-loop helix (Fig. 3). Kinesin motor domains share a close structural homology to myosin motor domains [49]. In myosins, the loop following the P-loop helix (called loop-1) is responsible for nucleotide affinity that decreases with the length and flexibility of this loop [50]. L6 might have a similar function in kinesin. The motor domain additionally contains a very long L12, having five positively charged residues in its sequence. This is similar to the K-loop composition in Kif1 kinesins from mammals. The tail of DdKif12 contains some predicted coiled-coil regions but does not show similarity to any protein in the databases.

Motors with multiple or unknown function

DdKif8 of the Kif4 subfamily and DdKif10 of the Kip3 subfamily belong to subfamilies members of which have been found to be involved in either mitosis or organelle transport, or which participate in both processes depending on the stages of the cell cycle.

DdKif8 (Kif4 subfamily)

The motor domain of DdKif8 contains the longest loop-10 (L10) of all sequenced kinesins, having about 70 extra residues compared to normal L10's (Fig. 3). L10 consists (from the N- to the C-terminus) of a serine/threonine linker, eight lysine residues (five consecutive), another serine linker and a stretch of 14 consecutive aspartic or glutamic acid residues, followed by a final linker. This loop is involved in neither nucleotide binding nor in the direct kinesin-microtubule interface, so its function was not yet analysed. Based on its length, it might be possible that the lysine part interacts with the E hook of tubule molecules in a similar way to the K loop of Unc104/Kif1A (a lysine rich L12) is suggested to function [51,52]. Further possible functions include interactions with other microtubule bound proteins. The stalk domain of DdKif8 is mostly α-helical, containing extended regions rich in polar residues and a coiled-coil domain. The C-terminus is built of seven WD-40 repeats which contribute to a seven-bladed beta propeller [53]. Blade five and blade six are separated by an unusually long insert of ~100 residues. WD40 domains are known to mediate protein-protein interactions [54] and the function of this domain in DdKif8 might be the binding of a specific protein cargo, either as part of a protein complex or as a receptor attached to an organelle.

DdKif10 (Kip3 subfamily)

Following the motor domain, DdKif10 is predicted to have some coiled-coil structure, interrupted by a negatively charged region mainly consisting of asparagines and aspartic acids. In the middle of the protein, there are two EF-hand binding domains, the first one having only weak homology. EF-hand motifs almost always occur in pairs, packed together in a face-to-face manner [55]. Their functions include the transduction of intracellular Ca2+ signals as well as Ca2+ uptake and buffering. Recent investigations also show that EF-hand domains are responsible for homo- and heterodimerisation [56,57]. Directly behind the second EF-hand motif, DdKif10 contains a stretch of almost 50 consecutive asparagine residues. The C-terminal domain is composed of α-helical and β-sheet structure, as well as a short predicted coiled-coil domain.

DdKif9 (not classified)

The motor domain of DdKif9 does not group with any of the other known kinesins and may therefore be the founder of a new class. Its motor domain is located in the centre of the molecule and contains one of the longest loop-5s (L5) of all kinesins (Fig. 3). L5 constitutes the interruption of the long α-2 helix C-terminal to the P-loop. In myosins, the length and flexibility of the loop following the P-loop helix (named loop-1) has a strong effect on nucleotide affinity [50,58]. Whether L5 has a similar influence on the affinity of kinesins to nucleotides was not yet analysed. The N-terminal domain is rich in amino acids proline, asparagine, serine and threonine, while the C-terminal domain is α-helical and predicted to form coiled-coils. The C-terminus is concluded with a transmembrane domain that might be the linker to membranous cargos.

Missing motors

Due to the broad diversity of the kinesin family, different evolutionary lineages have evolved different subfamilies with specialised functions. The only major subfamilies for which Dictyostelium does not contribute are the Osm3 (N-4) and Kif15 (N-10) kinesins.

Discussion

The nine subfamilies identified in the Dictyostelium genome are Unc104/Kif1 (DdKif1), Kif4 (DdKif8), NCD/Kar3 (DdKif2), KHC (DdKif3, DdKif5, DdKif7), BimC/Eg5 (DdKif13), CENP-E (DdKif4, DdKif11), MCAK/Kif2 (DdKif6), MKLP1 (DdKif12) and Kip3 (DdKif10). Kif9 could not be grouped to one of the already assigned subfamilies. Structurally, two of the kinesins (DdKif6 and DdKif9) are of the middle motor domain type, one (DdKif2) has the motor domain at the C-terminus and the remaining are N-terminal kinesins. Functionally, Dictyostelium contains some kinesins of the KHC and Unc104/Kif1 subfamily that have been shown to or are implicated to perform intracellular transport. To accomplish mitosis and cytokinesis, kinesins from all essential classes are available: BimC/Eg5, CENP-E, NCD/Kar3, MCAK/Kif2 and MKLP1. Additionally, Dictyostelium has two kinesins of the Kip3 and Kif4 subfamilies, members of which were shown to participate in either or both of the above mentioned processes in other organisms. Like most other species, Dictyostelium also has its unique kinesin (DdKif9) that has an unknown function. The only major subfamilies for which Dictyostelium does not contribute are the Osm3 (N-4) and Kif15(N-10) kinesins. Osm3 kinesins comprise a subfamily of mainly heterotrimeric motors built of two kinesin chains and a tightly associated subunit. They are involved in "intraflagellar transport" [1] and other specialised tasks such as the movement of vesicular cargo in neurons or pigmented melanosomes in melanophore cells. Kif15 kinesins are involved in mitosis by transiently positioning spindle poles, specifically during prometaphase [59] or by maintaining spindle bipolarity [60].

Organelle transporters

The Dictyostelium genome contains four kinesins belonging to subfamilies involved in organelle transport. Their biochemical properties and cellular functions have been discussed elsewhere [61].

Mitotic motors

The BimC/Eg5, CENP-E, NCD/Kar3, MCAK/Kif2 and MKLP1 subfamily members comprise the essential subset of kinesins necessary for mitosis of higher eukaryotes. DdKif13 is phylogenetically one of the most divergent BimC kinesins but has a similar domain organisation and contains the BimC motif. Therefore, it is expected to form a bipolar tetramer and is likely to fulfil the same function as other BimC kinesins. BimC kinesins work in close cooperation with C-terminal motors of the NCD/Kar3 subfamily to organise the spindle microtubules [15,17]. As NCD/Kar3 kinesins move to the minus ends of microtubules, they work in the opposite direction to the BimC kinesins causing contraction of the spindle. The spindle structure is therefore established and maintained by the smooth balance between NCD/Kar3 and BimC action. Dictyostelium also contains a kinesin of the NCD/Kar3 subfamily, namely DdKif2, which has been localised to mitotic spindles being enriched toward the spindle poles, as compared to spindle microtubules [32]. DdKif2 and DdKif13 are therefore the Dictyostelium kinesins responsible for the organisation of the spindle microtubules.

Dictyostelium contains two members of the CENP-E subfamily. Members of this subfamily bind to kinetochores during mitosis [62] and are responsible for the alignment of the chromosomes [63]. The two Dictyostelium members of the CENP-E subfamily, DdKif4 and DdKif11, are very different in all aspects. DdKif4 is phylogenetically more similar to the mammalian homologues, with a similar length and domain organisation, having only coiled-coil regions in its tail. As the nuclear envelope does not break down during mitosis of Dictyostelium cells, the nuclear localisation signal that lack mammalian homologues is obviously important for its destination. DdKif4 therefore likely operates in kinetochore binding and chromosome separation. DdKif11 is by far the shortest of the Dictyostelium kinesins. It groups to the plant members of the CENP-E subfamily that are very diverse in length. None of these plant kinesins has been functionally analysed, so it has yet to be determined whether they have a similar function to their mammalian homologues. DdKif11 also has a PDZ domain-binding motif. These motifs are implicated in transport, localization and assembly of supramolecular signalling complexes [39]. It is therefore unlikely that DdKif4 and DdKif11 have entirely overlapping functions.

Another kinesin with expected function in mitosis is DdKif6, belonging to the MCAK/Kif2 subfamily. MCAK/Kif2 kinesins have been shown to depolymerise microtubules in vitro [20,23]. This is consistent with their observed function in vivo where their inhibition interferes with the poleward movement of chromosomes during anaphase A [22], a process being associated with the shortening of the microtubules that connect the chromosomes to the poles. In addition to the well-conserved motor domain, Kif6 contains a SAM domain at its N-terminus. The phylogenetically closest related metazoan members of the subtree (LemKif4 and MmKif24) also have a SAM domain at their N-terminus. The self-association of SAM domains has been known for some time to play a regulatory role in proteins involved in the regulation of developmental processes among diverse eukaryotes [44]. For example, in Dictyostelium cells, the levels of DPYK1, a SAM-containing protein-tyrosine kinase, increase as the cells initiate their signal-mediated developmental cycle [64]. The SAM domain of DdKif6 might therefore be the reason for its observed developmental regulation [30].

DdKif12 groups to the MKLP1 subfamily. Based on their amino acid sequence, MKLP1 kinesins are characterised by their extremely long L6, the loop following the P-loop helix. The specific function of this loop has not yet been analysed in detail but from the close structural similarity of the kinesin motor domain to the motor domain of myosins [49], this loop might be involved in determining nucleotide affinity. Mammals have three kinesins of this subfamily of different length and domain organisation. CHO1 (Kif23), the most extensively analysed MKLP1 kinesin, is involved in mitosis and has been shown to mediate antiparallel microtubule sliding [65], most probable by cross-linking antiparallel microtubules by its second, nucleotide insensitive microtubule binding site [66]. Rab6-Kif (Kif20A) also functions in cell division during cleavage furrow formation and cytokinesis [67] but additionally localises to the Golgi apparatus and plays a role in the dynamics of this organelle [68]. In addition to their tasks during mitosis, some MKLP1 kinesins might thus perform other functions during interphase and this might also be true for DdKif12.

Motors with multiple or unknown function

DdKif10 belongs to the Kip3 subfamily of kinesin motors. The only member of this subfamily that has been analysed yet is Kip3 from S. cerevisiae [25,26]. In contrast to ScKip3, DdKif10 contains EF-hand motifs in the tail. EF-hand motifs are implicated in the transduction of intracellular Ca2+ signals. DdKif10 might therefore fulfil several different functions during interphase and mitosis.

Another Dictyostelium kinesin potentially performing multiple functions is DdKif8, belonging to the Kif4 subfamily. Kif4 from mammals has been shown to function in the anterograde transport of certain organelles in juvenile neurons and other cells [69]. Furthermore, it colocalized at the mitotic spindle during mitosis, where it is associated with chromosomes [70]. DdKif8 was found to be constitutively expressed [30]. Its tail contains seven WD40 repeats, which are also found in mammalian Kif21 kinesins and other kinesins of this subfamily.

In recent years, the genomes of a number of eukaryotic organisms have been completely sequenced. In subsequent studies the full set of members of the kinesin superfamily were identified and classified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae [71], Saccharomyces pombe, Drosophila melanogaster [72], mouse and human [10], Arabidopsis thaliana [73] and Caenorhabditis elegans [74]. The Arabidopsis genome contains by far the most kinesin genes (61 Kif's; Table 2).

Table 2.

Subfamily distribution of kinesins from different organisms and comparison of the number of kinesins to the total number of genes.

| Function* | H. sapiens | D. melanogaster | C. elegans | D. discoideum | A. thaliana | S. pombe | S. cerevisae | |

| Number of kinesin genes | 45 | 24 | 20 | 13 | 62 | 9 | 6 | |

| N-1 (KHC) | + | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| N-2 (BimC/Eg5) | ++ | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| N-3 (Unc104/Kif1) | + | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||

| N-4 (Osm3) | + | 4 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| N-5 (Kif4) | + / ++ | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| N-6 (MKLP1) | ++ | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| N-7 (CENP-E) | ++ | 1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |||

| N-8 (Kip3) | + / ++ | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| N-9 (Kif12) | +++ | 1 | 1 | |||||

| N-10 (Kif15) | ++ | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||||

| N-11 (Kif26) | +++ | 2 | 1 | |||||

| N-12 (Kif6) | +++ | 2 | ||||||

| N-13 (Kip2) | ++ | 1 | 1 | |||||

| N-14 (Nack) | +++ | 8 | ||||||

| N-15 (Kif7) | +++ | 1 | ||||||

| N-16 (Kid) | ++ | 1 | ||||||

| N-17 (Tbk5) | +++ | 2 | ||||||

| M-1 (MCAK/Kif2) | ++ | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| M-2 (KATD) | +++ | 12 | ||||||

| C-1 (NCD/Kar3) | ++ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| C-2 | + | 1 | ||||||

| C-3 | +++ | 1 | ||||||

| C-4 (KCBP) | ++ | 1 | ||||||

| Not classified | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | |

| Predicted number of genes | ~30000 | 13601 | 18424 | ~11000 | 25498 | 4824 | 6241 | |

| Percentage of kinesins [%] | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.10 |

* + = organelle transport; ++ mitosis; +++ unclear or unknown function.

Some of the kinesin subfamilies only include members from specific kingdoms. The N-14, N-17, M-2, and C-4 classes are plant specific, the N-13 subfamily exclusively harbours yeast members and only mammals contribute to a special class of C-terminal kinesins (C-2) as well as to the N-15 kinesins. The N-9 and N-11 subfamilies are, as yet, reserved for members of the metazoan subkingdom. This is similar to results of the analysis of the myosin superfamily, which also showed that some classes are restricted to specific kingdoms. Taking into account that the yet to be classified kinesins will appear as members of new classes, the mammalian genomes comprise by far the highest diversity, harbouring kinesins of 19 subfamilies.

Compared to the other completed genomes, Dictyostelium has a similar percentage of kinesin genes. The thirteen kinesins group into nine characterised subfamilies and one new class. This subfamily diversity is comparable to that observed for the Drosophila and C. elegans genomes. While Dictyostelium mostly contributes only one member to the subfamilies, more complex organisms show additional diversity, often having several members per subfamily.

Conclusions

This analysis of the Dictyostelium genome led to the identification of eight new kinesin motor proteins. According to an exhaustive phylogenetic comparison, Dictyostelium contains the same subset of kinesins that higher eukaryotes need to perform mitosis. Some of the kinesins are implicated in intracellular traffic and a few have unpredictable functions.

Methods

Identification of Dictyostelium kinesins

The full-length sequences of DdKif1, DdKif2, DdKif5, DdKif7 and DdKif9 have been reported in the literature. Additionally, for DdKif4 the mRNA sequence is available, differing from the genomic sequence by a gap of about 100 bp that is, however, dubious. The whole dataset generated by the Dictyostelium Sequencing Consortium http://genome.imb-jena.de/dictyostelium; http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu; http://www.sanger.ac.uk; http://www.uni-koeln.de/dictyostelium; http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/unites/gmp/sitesgmp/gmp_projects.html was used to search for kinesin domains. For this purpose, all available raw reads were translated into all six reading frames and subsequently examined for the presence of Interpro domains IPR000857, IPR001752, IPR002151, and IPR008658 http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro. All reads containing at least parts of the domains were sampled and assembled together with adjacent sequence reads. The assembly was performed using the Staden package http://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/pubseq/staden_home.html. To obtain contigs containing the full length genes, reads were added to the contigs until the gene prediction software geneid predicted the same gene structure for the kinesin domain containing genes independently from the contig length. Furthermore, all six reading frames of contigs larger than 1 kb resulting from a phrap based assembly of all sequences were scanned for the presence of these domains. One kinesin domain-containing gene (kif11) could only be detected by the single read examination, indicating that the phrap based assembly failed to produce larger contigs in this particular genomic region. Taking advantage of uneven distributions of reads derived from different chromosome specific libraries, the predicted kinesin domain containing genes were assigned to specific chromosomes. Each predicted gene was checked for matching ESTs from the Japanese cDNA project. Most of the predicted genes could at least partly be covered by EST sequences indicating expression of the genes. Only for kif 5 and kif 9 was no EST available. This may be due to the fact that most of the ESTs were derived from cells entering the sexual or developmental cycle.

Building trees

The motor domain of DdKif1 was used in a BLASTP search using the WU-BLAST2 server at EMBL http://dove.embl-heidelberg.de/Blast2/; [75]). The sequences obtained were compared with recent compilations of kinesin sequences [3,10,73] and missing sequences were manually added. Altogether 377 kinesin sequences from 50 species were obtained (see supplemental material) and aligned together with the thirteen Dictyostelium kinesins using ClustalW [76] software. The alignment showed that especially the sequences of kinesins from L. major and P. falciparum were misaligned because of the many unusual insertions (extended loops). The crude alignment was extensively manually improved according to the conserved secondary structural elements of the motor domain, which were obtained from a superposition of all crystal structures (Kollmar, unpublished data). An unrooted phylogenetic tree was generated using the Bootstrap (1,000 replicates) method implemented in ClustalW (standard settings) and drawn by using TreeView [77]. The tree did not change considerably when a correction for multiple substitutions was applied, nor did it change when 10,000 replicates were used.

Authors' contributions

MK designed the study, performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. GG identified and assembled the kinesin sequences, performed data analysis and assisted in writing the manuscript. Both authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Sequence access information for kinesin-like proteins found in the common databases.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank J.M. Scholey for helpful comments and C. Griesinger for discussions and continuous support. Sequences searched in this study were generated as part of the Dictyostelium Genome Project by A. Kuspa and R. Gibbs (The Baylor Sequencing Center, Houston, Tex.; sequencing supported by the National Institutes of Health); G. Glöckner, M. Platzer, L. Eichinger and A. Noegel (the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology, Jena, Germany together with the Institute of Biochemistry, Cologne, Germany); and M.-A. Rajandream and B. Barrell (the EUDICT consortium, supported by The European Union). Sequence data for D. discoideum was obtained from the Genome Sequencing Centre Jena website at http://genome.imb-jena.de/dictyostelium/. The German part of the D. discoideum Genome Project is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (No 113/10-1, No 113/10-2, and Pl173/5-2). M.K. is supported by a Liebig Stipendium of the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, which is in part financed by the BMBF.

Contributor Information

Martin Kollmar, Email: mako@nmr.mpibpc.mpg.de.

Gernot Glöckner, Email: gernot@imb-jena.de.

References

- Vale RD. The molecular motor toolbox for intracellular transport. Cell. 2003;112:467–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge T, Cope MJ. A myosin family tree. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3353–4. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.19.3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AJ, Endow SA. A kinesin family tree. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3681–2. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM. AAA domains and organization of the dynein motor unit. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2521–6. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.14.2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale RD, Reese TS, Sheetz MP. Identification of a novel force-generating protein, kinesin, involved in microtubule-based motility. Cell. 1985;42:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady ST. A novel brain ATPase with properties expected for the fast axonal transport motor. Nature. 1985;317:73–5. doi: 10.1038/317073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach RJ, Mackay JP, Armati PJ, Cunningham AL. The C-terminal region of the stalk domain of ubiquitous human kinesin heavy chain contains the binding site for kinesin light chain. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16663–70. doi: 10.1021/bi981163r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endow SA. Determinants of molecular motor directionality. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:E163–7. doi: 10.1038/14113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovechkina Y, Wordeman L. Unconventional motoring: an overview of the kin C and kin I kinesins. Traffic. 2003;4:367–75. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki H, Setou M, Kaneshiro K, Hirokawa N. All kinesin superfamily protein, KIF, genes in mouse and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7004–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111145398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N. Kinesin and dynein superfamily proteins and the mechanism of organelle transport. Science. 1998;279:519–26. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekawa Y, Harada A, Okada Y, Funakoshi T, Kanai Y, Takei Y, Terada S, Noda T, Hirokawa N. Defect in synaptic vesicle precursor transport and neuronal cell death in KIF1A motor protein-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:431–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray K, Perez SE, Yang Z, Xu J, Ritchings BW, Steller H, Goldstein LS. Kinesin-II is required for axonal transport of choline acetyltransferase in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:507–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp DJ, McDonald KL, Brown HM, Matthies HJ, Walczak C, Vale RD, Mitchison TJ, Scholey JM. The bipolar kinesin, KLP61F, cross-links microtubules within interpolar microtubule bundles of Drosophila embryonic mitotic spindles. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:125–38. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp DJ, Rogers GC, Scholey JM. Microtubule motors in mitosis. Nature. 2000;407:41–7. doi: 10.1038/35024000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashina AS, Baskin RJ, Cole DG, Wedaman KP, Saxton WM, Scholey JM. A bipolar kinesin. Nature. 1996;379:270–2. doi: 10.1038/379270a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp DJ, Rogers GC, Scholey JM. Roles of motor proteins in building microtubule-based structures: a basic principle of cellular design. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1496:128–41. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(00)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabay A, Walker RA. Identification of microtubule binding sites in the Ncd tail domain. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1838–49. doi: 10.1021/bi981850i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama R, Gustus C, Terada Y, Uetake Y, Matuliene J. CHO1, a mammalian kinesin-like protein, interacts with F-actin and is involved in the terminal phase of cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:783–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Verma S, Mitchison TJ, Walczak CE. Kin I kinesins are microtubule-destabilizing enzymes. Cell. 1999;96:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wordeman L, Mitchison TJ. Identification and partial characterization of mitotic centromere-associated kinesin, a kinesin-related protein that associates with centromeres during mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:95–104. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maney T, Hunter AW, Wagenbach M, Wordeman L. Mitotic centromere-associated kinesin is important for anaphase chromosome segregation. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:787–801. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AW, Caplow M, Coy DL, Hancock WO, Diez S, Wordeman L, Howard J. The kinesin-related protein MCAK is a microtubule depolymerase that forms an ATP-hydrolyzing complex at microtubule ends. Mol Cell. 2003;11:445–57. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00049-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke CA, Schaar B, Yen TJ, Earnshaw WC. Localization of CENP-E in the fibrous corona and outer plate of mammalian kinetochores from prometaphase through anaphase. Chromosoma. 1997;106:446–55. doi: 10.1007/s004120050266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RK, Heller KK, Frisen L, Wallack DL, Loayza D, Gammie AE, Rose MD. The kinesin-related proteins, Kip2p and Kip3p, function differently in nuclear migration in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2051–68. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeZwaan TM, Ellingson E, Pellman D, Roof DM. Kinesin-related KIP3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for a distinct step in nuclear migration. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1023–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.5.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati T, Geissler H, Schwarz EC. How many is enough? Exploring the myosin repertoire in the model eukaryote Dictyostelium discoideum. Cell Biochem Biophys. 1999;30:389–411. doi: 10.1007/BF02738121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus MA. The role of unconventional myosins in Dictyostelium endocytosis. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2000;47:191–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2000.tb00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey G, Vale RD. Identification of a kinesin-like microtubule-based motor protein in Dictyostelium discoideum. Embo J. 1989;8:3229–34. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hostos EL, McCaffrey G, Sucgang R, Pierce DW, Vale RD. A developmentally regulated kinesin-related motor protein from Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2093–106. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock N, de Hostos EL, Turck CW, Vale RD. Reconstitution of membrane transport powered by a novel dimeric kinesin motor of the Unc104/KIF1A family purified from Dictyostelium. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:493–506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai S, Suyama E, Adachi H, Sutoh K. Characterization of a C-terminal-type kinesin-related protein from Dictyostelium discoideum. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:47–51. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner G, Eichinger L, Szafranski K, Pachebat JA, Bankier AT, Dear PH, Lehmann R, Baumgart C, Parra G, Abril JF, et al. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 2 of Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature. 2002;418:79–85. doi: 10.1038/nature00847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichinger L, Noegel AA. NEW EMBO MEMBER'S REVIEW: Crawling into a new era-the Dictyostelium genome project. Embo J. 2003;22:1941–6. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demerec M, Adelberg EA, Clark AJ, Hartman PE. A proposal for a uniform nomenclature in bacterial genetics. Genetics. 1966;54:61–76. doi: 10.1093/genetics/54.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuspa A, Loomis WF. Ordered yeast artificial chromosome clones representing the Dictyostelium discoideum genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5562–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DF, Bryant PJ. ZO-1, DlgA and PSD-95/SAP90: homologous proteins in tight, septate and synaptic cell junctions. Mech Dev. 1993;44:85–9. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Fanning AS, Fu C, Xu J, Marfatia SM, Chishti AH, Crompton A, Chan AC, Anderson JM, Cantley LC. Recognition of unique carboxyl-terminal motifs by distinct PDZ domains. Science. 1997;275:73–7. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung AY, Sheng M. PDZ domains: structural modules for protein complex assembly. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5699–702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck MM, Pereira A, Pesavento P, Yannoni Y, Spradling AC, Goldstein LS. The kinesin-like protein KLP61F is essential for mitosis in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:665–79. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawin KE, Mitchison TJ. Mutations in the kinesin-like protein Eg5 disrupting localization to the mitotic spindle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4289–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blangy A, Lane HA, d'Herin P, Harper M, Kress M, Nigg EA. Phosphorylation by p34cdc2 regulates spindle association of human Eg5, a kinesin-related motor essential for bipolar spindle formation in vivo. Cell. 1995;83:1159–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponting CP. SAM: a novel motif in yeast sterile and Drosophila polyhomeotic proteins. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1928–30. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Ponting CP, Hofmann K, Bork P. SAM as a protein interaction domain involved in developmental regulation. Protein Sci. 1997;6:249–53. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WK, Proctor MR, Buckle AM, Bycroft M, Chen YW. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic studies of a SAM domain at the C-terminus of human p73alpha. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:769–71. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos CD, Faham S, Goodwill KE, Cascio D, Phillips M, Bowie JU. Monomeric structure of the human EphB2 sterile alpha motif domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37301–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WK, Bycroft M, Foster NW, Buckle AM, Fersht AR, Chen YW. Structure of the C-terminal sterile alpha-motif (SAM) domain of human p73 alpha. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:545–51. doi: 10.1107/S0907444901002529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Cerretti DP, Daniel TO. Ligand activation of ELK receptor tyrosine kinase promotes its association with Grb10 and Grb2 in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23588–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale RD. Switches, latches, and amplifiers: common themes of G proteins and molecular motors. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:291–302. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CT, Spudich JA. The sequence of the myosin 50–20 K loop affects Myosin's affinity for actin throughout the actin-myosin ATPase cycle and its maximum ATPase activity. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3785–92. doi: 10.1021/bi9826815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa M, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. 15 A resolution model of the monomeric kinesin motor, KIF1A. Cell. 2000;100:241–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81562-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Hirokawa N. Mechanism of the single-headed processivity: diffusional anchoring between the K-loop of kinesin and the C terminus of tubulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:640–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer EJ, Schmidt CJ, Nambudripad R, Smith TF. The ancient regulatory-protein family of WD-repeat proteins. Nature. 1994;371:297–300. doi: 10.1038/371297a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TF, Gaitatzes C, Saxena K, Neer EJ. The WD repeat: a common architecture for diverse functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:181–5. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MR, Chazin WJ. Structures of EF-hand Ca(2+)-binding proteins: diversity in the organization, packing and response to Ca2+ binding. Biometals. 1998;11:297–318. doi: 10.1023/A:1009253808876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford C, Brown NR, Willis AC. Studies of the active site of m-calpain and the interaction with calpastatin. Biochem J. 1993;296:135–42. doi: 10.1042/bj2960135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Goll DE. Binding of calpain fragments to calpastatin. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11842–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollmar M, Durrwang U, Kliche W, Manstein DJ, Kull FJ. Crystal structure of the motor domain of a class-I myosin. Embo J. 2002;21:2517–25. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers GC, Chui KK, Lee EW, Wedaman KP, Sharp DJ, Holland G, Morris RL, Scholey JM. A kinesin-related protein, KRP(180), positions prometaphase spindle poles during early sea urchin embryonic cell division. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:499–512. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boleti H, Karsenti E, Vernos I. Xklp2, a novel Xenopus centrosomal kinesin-like protein required for centrosome separation during mitosis. Cell. 1996;84:49–59. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80992-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klopfenstein DR, Holleran EA, Vale RD. Kinesin motors and microtubule-based organelle transport in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2002;23:631–8. doi: 10.1023/A:1024403006680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Anderson KL, Cleveland DW. The microtubule-dependent motor centromere-associated protein E (CENP-E) is an integral component of kinetochore corona fibers that link centromeres to spindle microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:435–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan GK, Schaar BT, Yen TJ. Characterization of the kinetochore binding domain of CENP-E reveals interactions with the kinetochore proteins CENP-F and hBUBR1. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:49–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan JL, Spudich JA. Developmentally regulated protein-tyrosine kinase genes in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3578–83. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferhat L, Kuriyama R, Lyons GE, Micales B, Baas PW. Expression of the mitotic motor protein CHO1/MKLP1 in postmitotic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:1383–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama R, Dragas-Granoic S, Maekawa T, Vassilev A, Khodjakov A, Kobayashi H. Heterogeneity and microtubule interaction of the CHO1 antigen, a mitosis-specific kinesin-like protein. Analysis of subdomains expressed in insect sf9 cells. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:3485–99. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill E, Clarke M, Barr FA. The Rab6-binding kinesin, Rab6-KIFL, is required for cytokinesis. Embo J. 2000;19:5711–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echard A, Jollivet F, Martinez O, Lacapere JJ, Rousselet A, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Goud B. Interaction of a Golgi-associated kinesin-like protein with Rab6. Science. 1998;279:580–5. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti D, Peris L, Rosso S, Quiroga S, Caceres A. Evidence for the involvement of KIF4 in the anterograde transport of L1-containing vesicles. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:141–52. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YM, Lee S, Lee E, Shin H, Hahn H, Choi W, Kim W. Human kinesin superfamily member 4 is dominantly localized in the nuclear matrix and is associated with chromosomes during mitosis. Biochem J. 2001;360:549–56. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt ER, Hoyt MA. Mitotic motors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1496:99–116. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LS, Gunawardena S. Flying through the drosophila cytoskeletal genome. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:F63–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.2.F63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AS, Day IS. Kinesins in the Arabidopsis genome: A comparative analysis among eukaryotes. BMC Genomics. 2001;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui SS. Metazoan motor models: kinesin superfamily in C. elegans. Traffic. 2002;3:20–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YP, Eulenstein O, Vingron M, Bork P. Towards detection of orthologues in sequence databases. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:285–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DG, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:383–402. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RD. TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kull FJ, Sablin EP, Lau R, Fletterick RJ, Vale RD. Crystal structure of the kinesin motor domain reveals a structural similarity to myosin. Nature. 1996;380:550–5. doi: 10.1038/380550a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequence access information for kinesin-like proteins found in the common databases.