Abstract

Mechanical forces associated with blood flow play important roles in the acute control of vascular tone, the regulation of arterial structure and remodeling, and the localization of atherosclerotic lesions. Major regulation of the blood vessel responses occurs by the action of hemodynamic shear stresses on the endothelium. The transmission of hemodynamic forces throughout the endothelium and the mechanotransduction mechanisms that lead to biophysical, biochemical, and gene regulatory responses of endothelial cells to hemodynamic shear stresses are reviewed.

I. INTRODUCTION

The mechanical environment of mammalian cells is defined by complex interactions between gravitational forces, local forces generated by air and fluid pressure and movement, and intracellular tension arising from the organization of cytoskeletal elements. With the exception of the blood, the cellular components of vertebrate tissues develop tension by physical interactions with extracellular matrix and neighboring cells, the fundamental importance of which is reflected in adhesion-dependent expression of normal cell differentiation, growth, and function. Simple responses to external forces in unicellular organisms have evolved in mammals into sophisticated acute sensory systems and adaptive responses to sustained changes of the mechanical environment. In the mammalian cardiovascular system, unique responses to fluid forces are present in the endothelium.

The endothelium is located between flowing blood and the vascular wall. Cells lining the arterial circulation are exposed to fluid forces of much greater magnitude than those experienced by other mammalian tissues. Consequently, mechanically related responses controlled by the endothelium have evolved as part of normal vascular physiology, most notably in the control of vascular tone where mechanisms responsible for the transmission and transduction of hemodynamic information from the blood to the underlying vessel wall reside in the endothelium. Hemodynamic forces also play an important role in vascular pathologies, particularly in relation to the localization of atherosclerotic lesions.

The principal functions of endothelium are the maintenance of anticoagulant properties, the physiological control of lumen diameter, the regulation of vascular permeability, and the pathological consequences associated with acute inflammation, wound healing, and cardiovascular disorders such as the focal localization of atherosclerosis. In all of these processes, hemodynamic factors (defined as mechanical forces in the flowing blood) influence endothelial biology either by the direct action of shear stress and stretch forces on the endothelium itself or by indirect modification of the local concentrations of chemicals and agonists at the endothelial surface, thereby influencing association between these molecules and their endothelial receptors. In reality, the mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; direct forces acting on surface enzymes and receptors may modify enzyme-substrate and agonist-receptor interactions at the same time that the surface concentration of agonist is being influenced by convective and diffusive transport. A major challenge to researchers in this field is identification of the mechanism(s) by which flow forces in the blood are detected and converted in the endothelial cells into a sequence of biological responses. Despite a multiplicity of flow-sensitive mechanisms, it is plausible that discrete flow sensors or mechanoreceptors exist in the endothelial cell, intervention with which would have important consequences for many vascular events.

The main objectives of this review are 1) to document the current state of knowledge concerning endothelial responses to mechanical forces related to blood flow, 2) to propose response mechanisms that accommodate sometimes inconsistent or contradictory data, and 3) to suggest future directions of research into endothelial mechanotransduction. The review is focused principally on hemodynamic shear stress-related mechanisms.

II. FLOW IN THE ARTERIAL CIRCULATION

The flow characteristics operating on the arterial side of the circulation (large elastic and muscular arteries through smaller arteries, arterioles, and precapillary vessels) generate a wide range of hemodynamic stresses that vary greatly in magnitude, frequency, and direction at the endothelial surface (77, 100, 109, 167, 169, 177, 267). The mechanics of blood flow are more complex than classical Poiseuille fluid dynamics that apply principally to steady flow in a rigid tube of circular cross section. In the arterial circulation, blood flow is pulsatile, blood is a non-Newtonian fluid (although near-Newtonian characteristics are sometimes valid), and the vessel is a compliant tube of changing cross-sectional shape and area with many side branches and bifurcations. However, with the application of the principles of fluid dynamics, with the use of experimental models of steady and pulsatile flow in rigid tubes and fixed arteries, and with the development of more accurate in vivo measurements of blood flow, some reasonable estimates of flow characteristics, and hence hemodynamic forces, can be made.

Forces acting on an artery due to blood flow can be resolved into two principal vectors. One is perpendicular to the wall and represents blood pressure, and the other acts parallel to the wall to create a frictional force, shear stress, at the surface of the endothelium (77, 109, 254). Although all of the vessel wall, including the endothelium, smooth muscle cells, and the extracellular matrix (collagen, elastin, proteoglycans), is subjected to stretch as a consequence of pulsatile pressure, the shear stress is received principally at the endothelial surface. There is slow transmural flow around smooth muscle cells that produces very low levels of shear stress, but this force is considered to be insignificant when compared with tensile stress in these cells. In large arteries, the mean wall shear stress is typically in the range of 20–40 dyn/cm2 in regions of uniform geometry and away from branch vessels. Because blood flow is pulsatile in these vessels, however, the velocity profile varies with the cardiac cycle to produce a range of shear stress and shear stress gradients. Furthermore, at curvatures in the arterial wall such as the aortic arch, and at bifurcations and near branches, the steady laminar flow is disrupted to create regions of separated flow that include recirculation sites (vortices) that may appear/disappear or elongate/shorten with the cardiac cycle (Fig. 1). Extremely complex forms of disturbed laminar and occasionally nonlaminar flow occur in large arteries. As discussed in section XII, such regions are often associated with a predisposition for atherosclerosis. In addition to these primary flow characteristics, lesser fluid motions can occur perpendicular to the principal flow direction (77). Such secondary flows, although of low velocities, modify the profile of the primary flow and thereby influence the shear stress acting at the vessel wall.

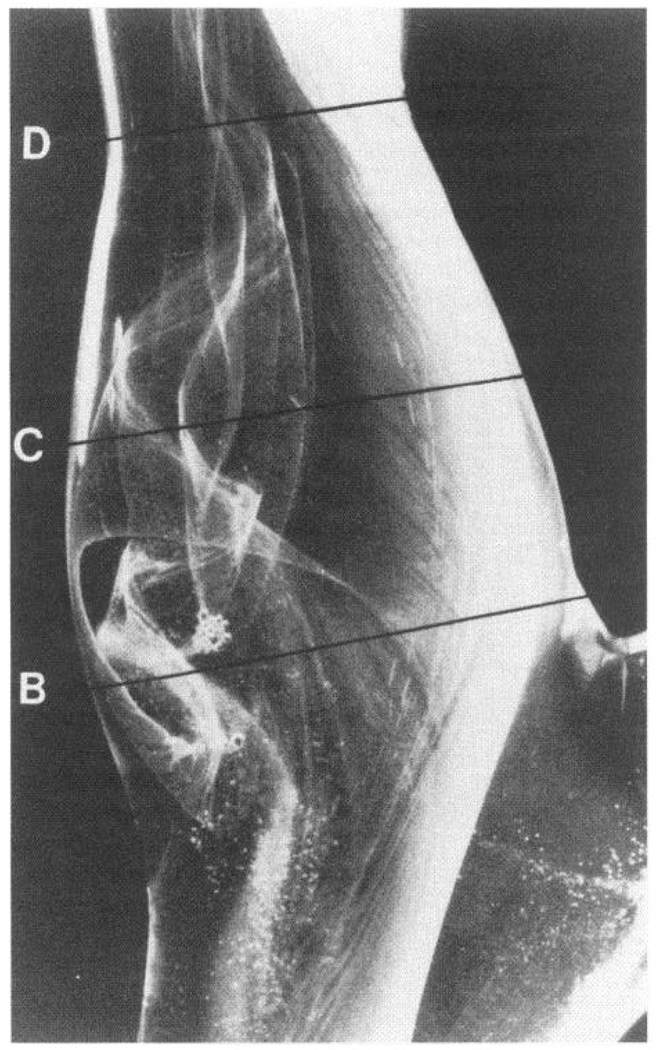

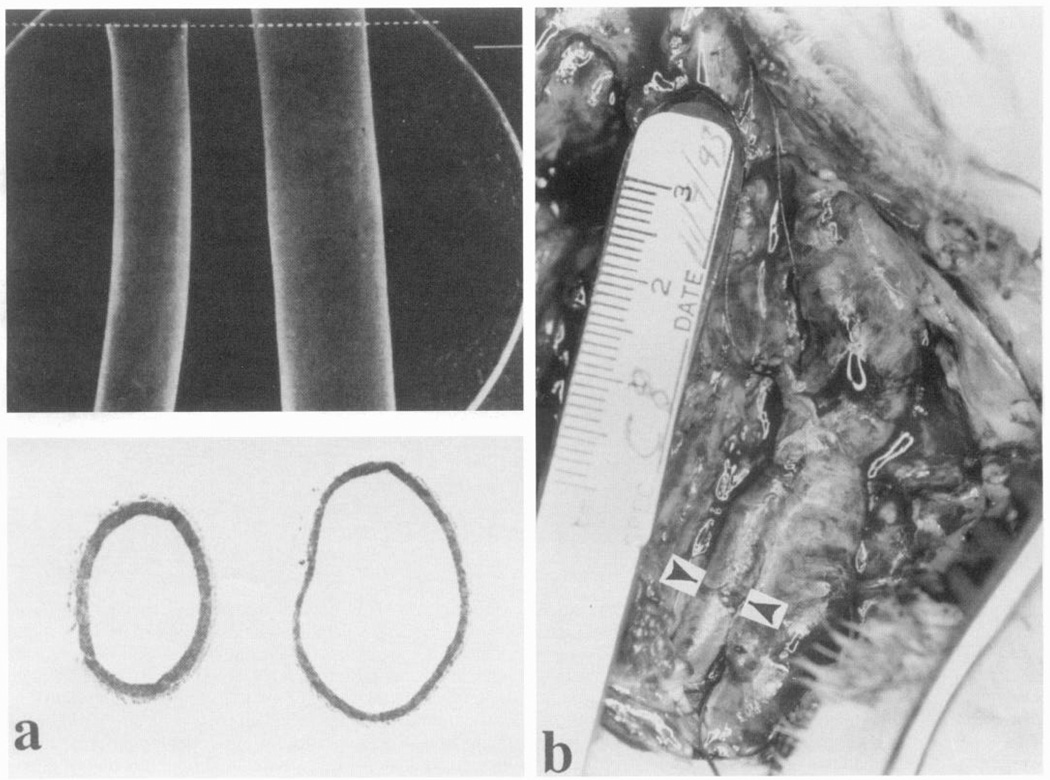

FIG. 1.

Glass model of human carotid sinus showing complex flow patterns visualized by hydrogen bubbles. In the sinus itself (B, C), there is separation of laminar flow profile to create a zone of recirculation that reattaches to main flow downstream (D). Vortices appear and disappear during pulsatile flow cycles. Note also helical pattern in main flow and absence of flow separation on opposite wall to sinus. Carotid artery atherosclerosis is common in region of flow separation. [From Zarins et al. (404).]

Models of arterial geometry and flow have been constructed that allow shear stress measurements to be estimated in vivo. Often, the morphology of endothelial cells lining real arteries accurately reflects the direction and magnitude of shear stress predicted from the models. Endothelial morphology is influenced by the prevailing hemodynamic conditions because the cells are malleable to the flow forces in vivo and in vitro; their alignment generally reflects the mean directional shear stress (78, 193, 194, 397). This is also true at regions of disturbed flow where the endothelial morphology changes abruptly over short distances (1–2 endothelial cells) from elongated alignment in the direction of flow to a configuration without preferred orientation (Fig. 2). The latter morphology is associated with disturbed flow regions of large arteries where the shear stress fluctuates in magnitude and changes direction during the cardiac cycle. From a large number of fluid dynamics studies combined with measurements and observations in real arteries, the range of shear stress in the arterial circulation in such regions has been estimated to vary from negative values, through zero values at the edges of flow separation regions, and up to values of ~40–50 dyn/cm2 (177, 178). During episodes of increased cardiac output or hypertension, these values may increase considerably; transients in excess of 100 dyn/cm2 have been recorded (77, 255). Much of the investigation of mechanotransduction of hemodynamic forces has been conducted in vitro, where control of the mechanical environment is more accessible than in vivo. The range of shear stresses examined in vitro has typically been 0– 100 dyn/cm2 mainly in steady unidirectional laminar flow, although more attention to the effects of pulsatile flow has recently been in evidence (133, 134).

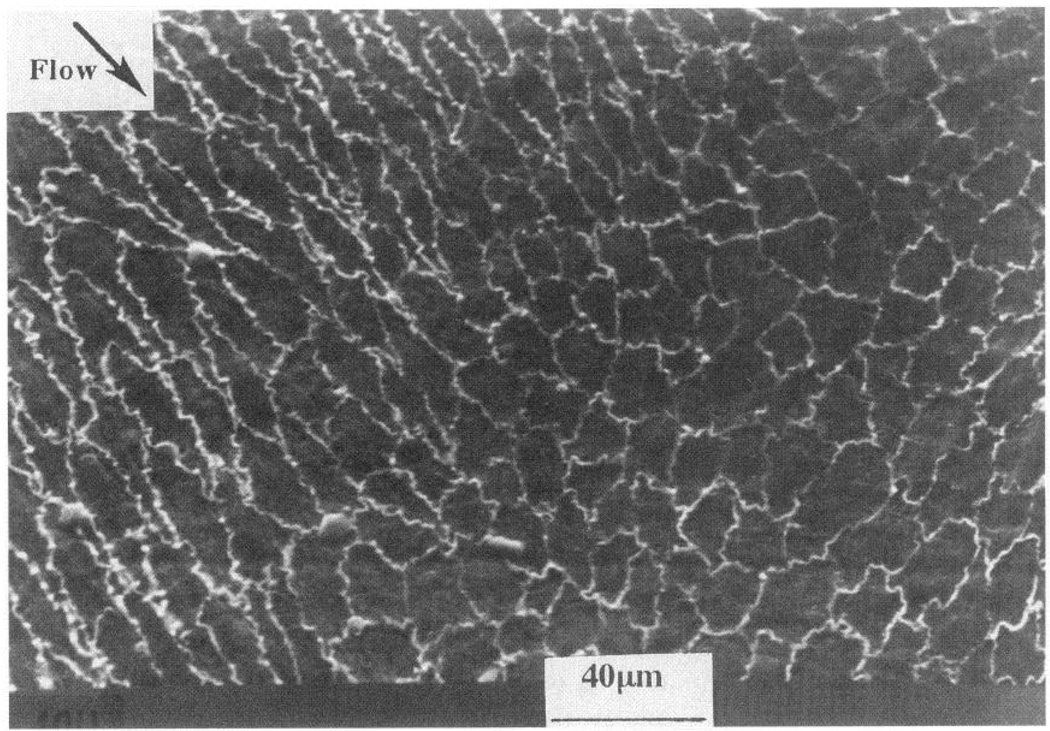

FIG. 2.

Outlines of endothelial cells in primate thoracic aorta adjacent to an intercostal branch artery. A region of predicted flow separation is shown in which shapes of cells change abruptly from elongated to polygonal (without preferred orientation). Polygonal morphology is believed to be caused by flow separation and vortices that subject endothelial surface to shear stress in several different directions during cardiac cycle. Adjacent cells are subjected to markedly different shear stress profiles. Gradients of shear stress are steepest on cells located at edge of flow separation region. Scanning electron micrograph is shown after silver staining.

III. MORPHOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO SHEAR STRESS

Since the early observations of silver-stained endothelial cells in the light microscope (1, 290), many investigators have documented a relationship between endothelial cell shape and orientation and the direction of blood flow (67, 90, 116, 187, 193, 194, 253, 268, 299). The cells align in the direction of flow. Flow separation, vortices, or other disturbances are reflected in the morphology, often as a loss of cell orientation (Fig. 2). The same is true in vitro (78, 85, 194, 300). The first demonstration that endothelial cellular morphology could be changed by flow was conducted in vivo by Flaherty et al. (90), who resected an arterial patch at 90° to its original orientation and observed that the endothelium subsequently realigned with the flow. A similar demonstration in vitro was first conducted by Dewey et al. (78), who induced cell alignment by applying unidirectional shear stress in steady flow to polygonal confluent endothelial monolayers.

In contrast, chaotic (turbulent) flow failed to align the cells (68), presumably because the direction, magnitude, and frequency of the forces were unpredictable. Cell shape and orientation are determined by the cytoskeleton, since it rearranges in response to flow. A prominent change occurs in the distribution of filamentous actin (F-actin) which in polygonal cells is organized as a dense band in the periphery of the cell. Upon exposure to shear stress, F-actin rearranges to create bundles of stress fibers (97, 169, 170, 225, 274, 390, 394). There is also evidence for the induction of F-actin (97). Attachment sites of stress fibers to the cell periphery (and associated extracellular molecules) also redistribute in response to flow (70, 64, 388, 389) as discussed in more detail in section V. The nature of the extracellular matrix appears to influence the rate of cytoskeleton reorganization (275). Endothelial morphological changes in flow have been reviewed extensively elsewhere (254, 255, 343).

IV. HEMODYNAMIC FORCE INTERACTIONS WITH THE ENDOTHELIUM

A. Forces and Cell Tension

1. Stress

The forces acting on, and within, a cell can be described in terms of stress. Stress is a force per unit area that has both normal components (tension and compression) and shear components. Stresses acting on the luminal surface of an endothelial cell cause internal stresses that are transmitted to abluminal attachment sites or to neighboring cells within the endothelial monolayer. Blood pressure acts normal to the cell surface creating a compressive stress within the cell, while the frictional force of flowing blood generates a shear stress acting tangentially to the cell surface. Furthermore, distension of the blood vessel due to the pressure pulse transmits tensile stress to the cell via its contacts with the extracellular matrix. Cell deformation in response to applied shear stress is expressed as strain and depends on the mechanical and structural properties of the cell. Tensile strain (stretch) represents a change in length per unit (original) length. In addition, torsional stresses may be imposed across the entire cell if its mechanical properties behave like a solid (103, 125), and osmotic pressure is under cellular control and must be balanced against externally applied hydrostatic pressure (385, 386). Endothelial cells are capable of altering their structure and mechanical properties resulting in the generation of intracellular stress, e.g., cytoskeletal reorganization in response to flow. Tension developed by the cytoskeleton is required for expression of differentiated properties of the endothelium. These mechanical terms, derived for inert materials, must be considered in the light of the active cellular metabolism of living endothelial cells.

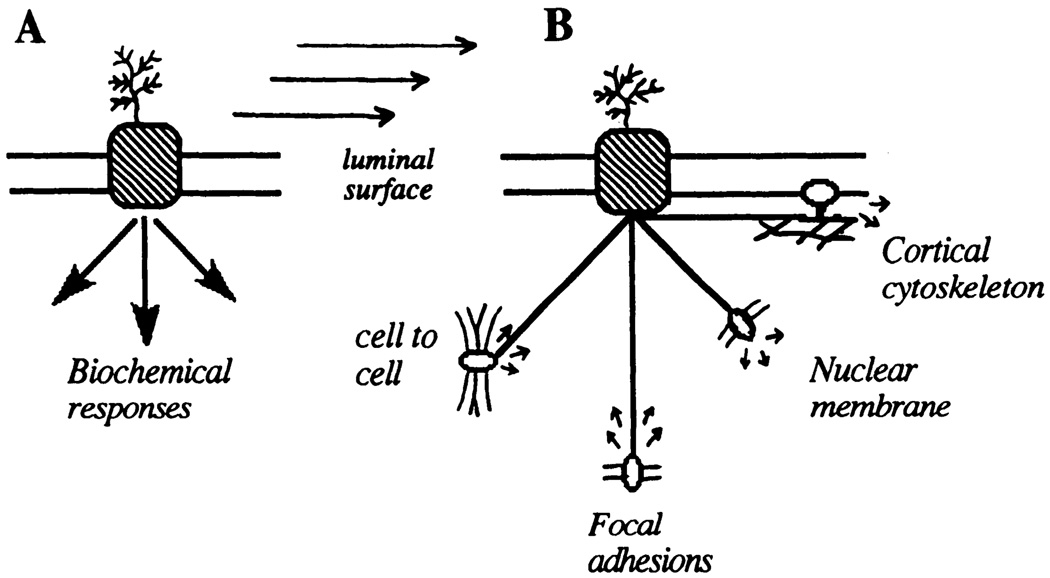

2. Force transmission

Anchorage-dependent cells, including endothelial cells, exist in a state of tension associated with the maintenance of cell shape. Such tension is generated when the cytoskeleton interacts with other regions of the cell, particularly at sites of adhesion to the subendothelial matrix (35), nucleus (286), and neighboring cells (361). When external forces are loaded onto the cell during flow, the internal cellular tension changes to equalize the external force. Therefore, direct shear stress-induced mechanotransduction in endothelial cells may occur by 1) local displacement of sensors at the cell surface, 2) force transmission via cytoskeletal elements to distribute the force throughout the cell, followed by 3) force transduction of the transmitted mechanical stress at mechanotransduction sites remote from the externally applied stress, or more likely a combination of these mechanisms (Fig. 3). Thus the cell is always under tension and responds to change of tension (347). Flow imposes additional changes of cell tension that lead to morphological and functional responses.

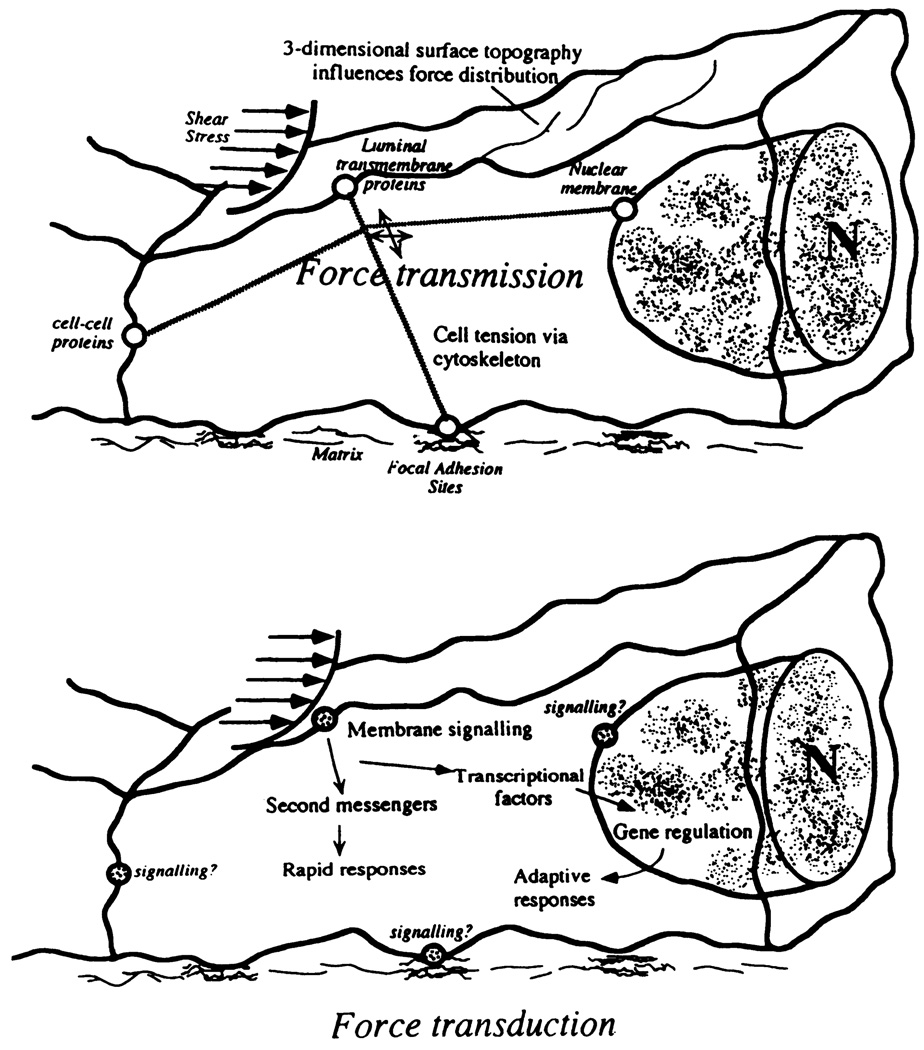

FIG. 3.

Separation of concepts of force transmission and force transduction. Cytoskeleton transfers stress to different regions of endothelial cell where mechanotransduction may occur. [From Davies and Barbee (61).]

The prominent reorganization of F-actin stress fibers, intermediate filaments, and microtubules to external forces (169, 389) implicates the cytoskeleton as a principal force transmission element in endothelial cells. Actin filaments are of particular interest in this regard because their association with transmembrane integrins appears to be the principal mechanism of the transmission of twisting forces across the plasma membrane (outside to inside; Ref. 383). Furthermore, the filaments also appear to be required for transduction because their disruption changes a number of primary and secondary responses in the endothelial cell. Consistent with this view, there is a change of stretch-activated ion channel activity in response to membrane deformation when actin filament structures are disrupted (318), and endothelial cell shape change, realignment to flow, focal adhesion remodeling, and gene regulation (243) are all inhibited by drugs that interfere with microfilament turnover.

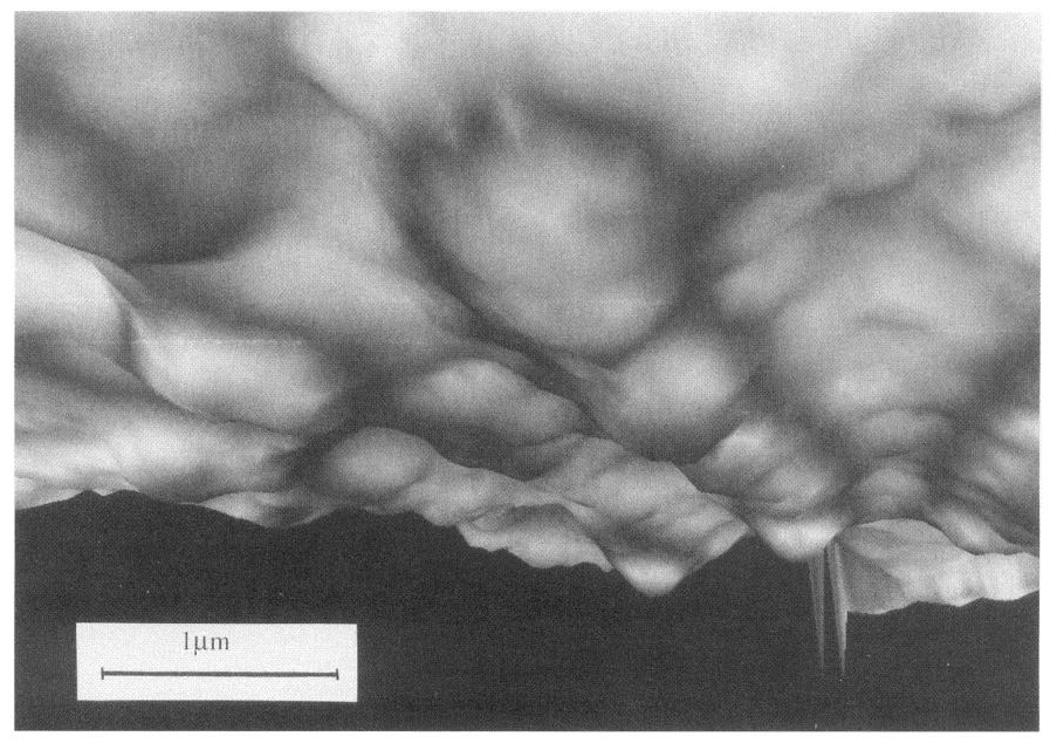

B. Topography of the Luminal Endothelial Surface

Hemodynamic force-cell interactions begin at the cell surface. In vitro experiments in which the applied forces were carefully controlled have demonstrated that endothelial behavior depends not only on the magnitude of shear stress but also on temporal and spatial variations of shear stress. Cell geometry, particularly surface topography, influences the magnitude and localization of hemodynamic forces acting at the endothelial surface and consequently affects the transmission of such forces across the plasma membrane and throughout the cell as outlined in Figure 3. However, efforts to relate molecular-scale transduction events to the physical stimuli at the cell surface have been frustrated by an insufficient characterization of the detailed distribution of fluid forces acting on the endothelium. Analyses of flow forces on a subcellular scale are needed to address the mechanisms of force transmission and its transduction into cellular responses. Knowledge of the flow characteristics in arteries provides a macroscopic profile of the flow and predicted shear stresses acting near the endothelial surface. However, the detailed real-flow behavior very close to the cell surface actually defines the cell responses. Only recently have estimates of its magnitude and spatial characteristics at a subcellular level been addressed. This was first attempted as a theoretical exercise by Satcher et al. (322), who modeled the endothelial monolayer as a wavy surface and used computational methods to estimate the influence of the waviness on local flow forces. Recently, it has been possible to image the geometry of living endothelial cells in tissue culture. Sakurai et al. (320) approximated the discontinuous contours of a single endothelial cell using differential interference contrast microscopy, an approach that was subsequently improved upon by the use of fluorescence exclusion combined with confocal microscopy (395). They estimated the shear stress to be considerably higher over the nuclear bulge, implying steep gradients of shear stress. However, the first images of the continuous geometry of the luminal surface of living endothelial cells at high resolution in real time were obtained by Barbee et al. (15) using atomic force microscopy (AFM; see Ref. 184 for a review of AFM). They reported major changes in the surface topography of cells aligned by flow compared with no-flow controls. The studies revealed significant changes in the height of the undulating endothelial monolayer when cells were aligned with flow; essentially a streamlining of the surface occurred (Fig. 4). In addition, there were localized changes of cell topography within individual endothelial cells that have implications for the local forces acting on different parts of the cell. The endothelial cell surface waviness (<6 µm) allows laminar flow to be considered as quasi-steady near the wall even in pulsatile arterial flow. From models, approximations, and actual measurements of the cell surface geometry, computational methods can be employed to study the flow very close to the cell surface to calculate shear stress distribution.

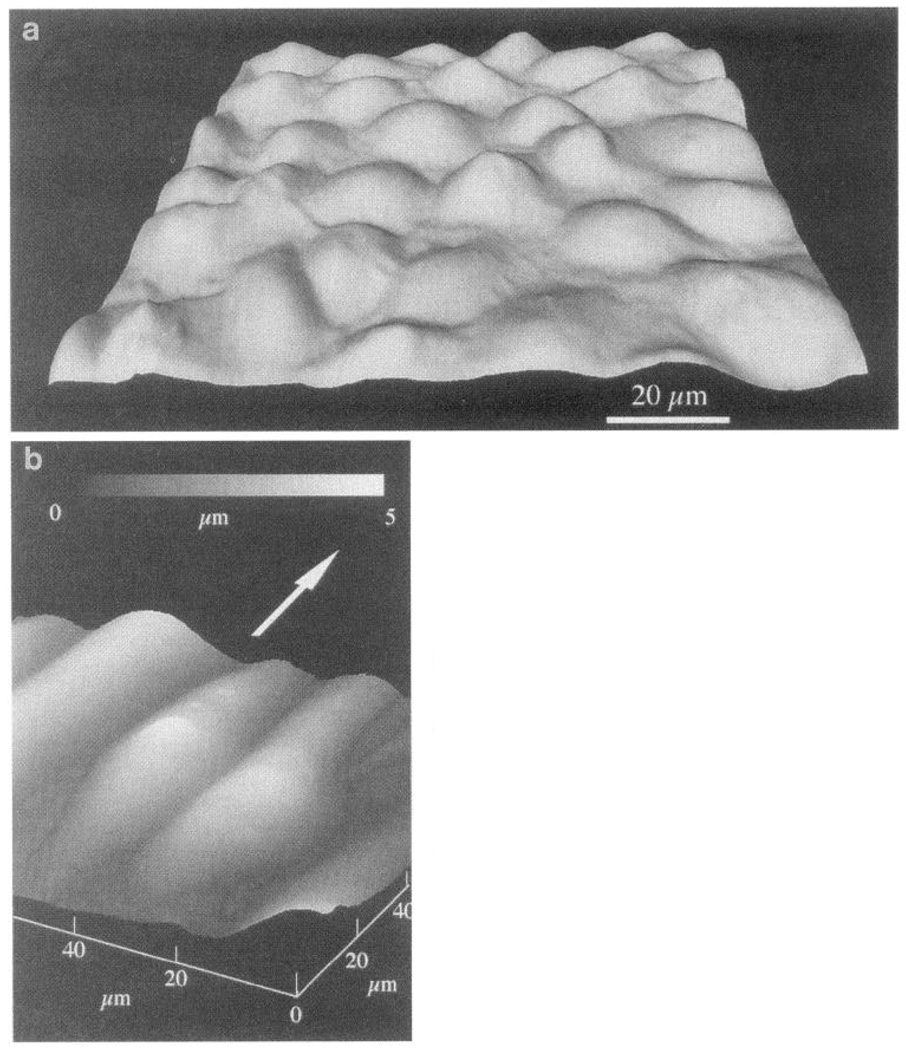

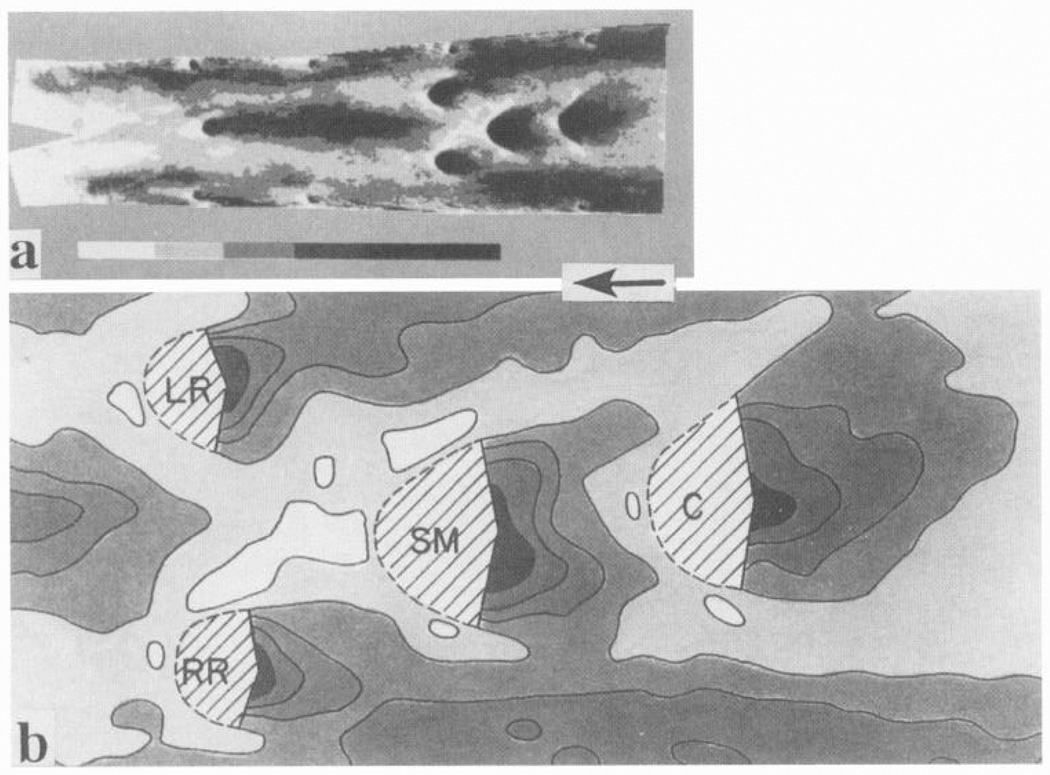

FIG. 4.

Atomic force microscope images of confluent bovine arotic endothelial cells. a: cultured under no-flow conditions. b: after 24-h exposure to 12-dyn/cm2 shear stress in steady laminar flow. Flattened profiles of aligned cells give rise to smaller spatial variations of shear stress and stress gradients at cell surface. Arrow indicates direction of flow. Gray micrometer scale in b indicates height of cell surface referenced to lowest point (at junctions between cells). (Images courtesy of Dr. Kenneth Barbee, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.)

Spectral element analyses have been conducted to simulate flows over endothelial surface geometries defined by AFM of living endothelial cells (16). The distribution of shear stress on the cell surface was then calculated. Flow perturbations due to the undulating surface produced cell-scale variations of shear stress magnitude and, hence, large shear stress gradients. Reorganization of the endothelial surface in response to prolonged exposure to steady flow resulted in significant reductions in the peak shear stresses and shear stress gradients compared with no-flow control cells (15, 16, 64). Whereas previously the stress acting on the cell surface was assumed to be spatially uniform and equal to the average wall shear stress determined by macroscopic flow dynamics, the new studies demonstrated that there are microscopic departures from a flat boundary due to the presence of the endothelial cells. These, in turn, caused a localized perturbation of the macroscopic flow field. From the point of view of the endothelial cell, the shear stress at the luminal surface will vary within the macroscopic flow field as a function of the surface geometry. Thus cells in certain morphological configurations are likely to be exposed to much lower shear stress gradients than neighboring cells. The consequences of this may be a resetting of the threshold levels necessary to elicit bioresponses in the flow field. For example, in aligned cells there was approximately a 40% decrease in the average shear stress gradients compared with no-flow control cells. A detailed analysis of the upstream/downstream symmetry of the cell surface in vitro has yet to be made; differences may reflect sensitivity to shear stress. In this regard, altered agonist sensitivity of endothelial cells in situ has been reported when the flow direction was altered (291). Whether this phenomenon is a reflection of the endothelial microgeometry awaits the completion of AFM imaging of endothelial cells in situ.

C. Cytoskeletal Elements Enable Force Transmission Throughout the Cell

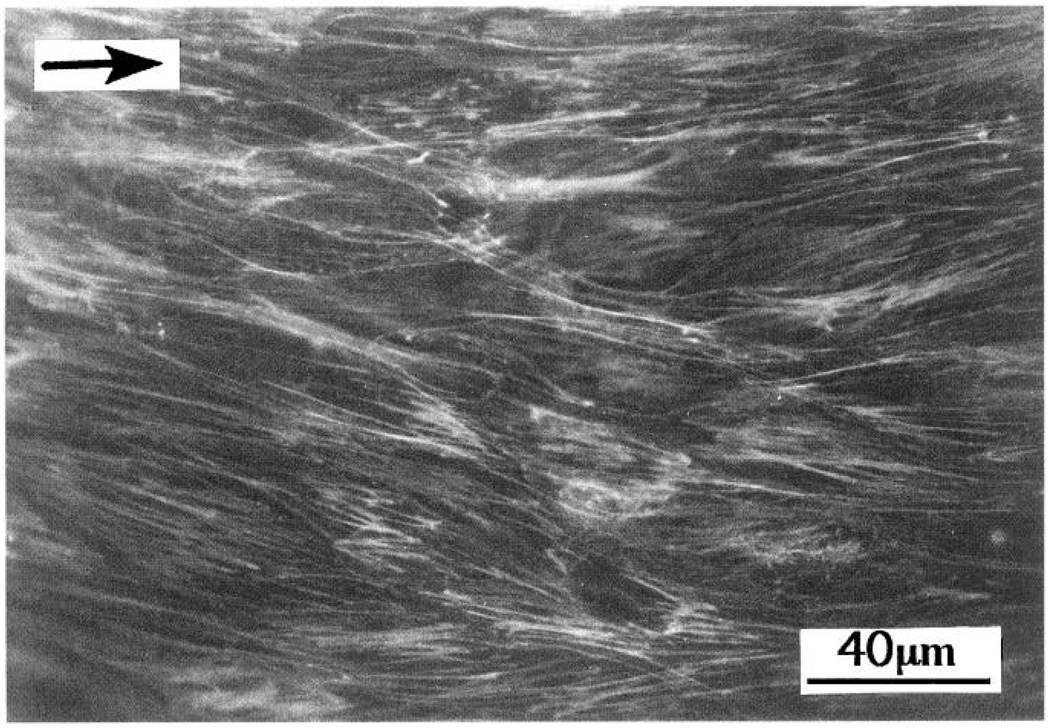

Prolonged exposure of endothelial cells to steady flow results in their realignment in the direction of flow, a process driven by reorganization of the cytoskeleton as demonstrated both in vitro (78, 388) and in situ (188, 390). Most observations have recordzed reorganization of actin microfilaments that change from a “banding pattern” around the cell periphery to a series of long, almost parallel fibers in the long axis of the aligned cell (Fig. 5). Although much attention is focused on F-actin because of its association with membrane proteins at the luminal and abluminal surfaces, the additional involvement of microtubules and vimentin-rich intermediate filaments (IF) should not be overlooked; both associate with plasma membrane proteins (356) and undergo alignment with unidirectional shear stress (F. W. Flitney, R. Goldman, and P. F. Davies; unpublished data). Unlike actin and tubulin, IF proteins are insoluble in the cytosol, and there are no soluble pools available for polymerization into filaments (59). Reorganization of endothelial IF during flow may therefore occur as a passive association of IF with F-actin that is undergoing remodeling through cycles of polymerization/depolymerization. Intermediate filaments also interact with microtubules via fibrous bridges (59). The dissolution of microtubules by colchicine results in clumping of IF. Thus there exist physical connections between these three important structural protein families that determine the shape of anchorage-dependent cells, and it is probable that a coordinated rearrangement occurs in endothelial cells subjected to flow. Until recently, only a limited appreciation of the spatial arrangements of the cytoskeleton was available from two-dimensional transmission electron micrographs. However, the development of three-dimensional reconstruction techniques from digitally imaged optical sections (4, 41, 242) and confocal imaging techniques (393) has now become economically feasible for less-specialized laboratories. Deconvolution techniques have recently been used to reconstruct endothelial cytoskeletal components from optical sections of fluorescence emissions collected in digitized form (A. Robotewskyj, M. L. Griem, J. Chen, and P. F. Davies; unpublished data). With the use of this approach, double (or triple) fluorescence labeling of cytoskel et al elements should reveal some of the physical relationships between them and how they change when mechanical stress is applied to the cell.

FIG. 5.

F-actin stress fiber distribution in aligned confluent endothelial cells. NBD-phallacidin stain was used. Arrow shows flow direction. [From Davies et al. (70). Reproduced from The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1993, vol. 91, p. 2640–2652 by copyright permission of The Society for Clinical Investigation.]

One of the most striking consequences of endothelial realignment by flow is increased resistance of the cell surface to deformation. This was first noted by Sato et al. (323) as decreased membrane deformability on micropipette aspiration of the cell surface after exposure to shear stress. Rather than stiffening of the membrane itself, however, it is the cortical cytoskeletal elements just beneath the membrane surface and attached to it that rearrange to a more rigid configuration. Using AFM, Barbee et al. (15) noted topographic features of aligned endothelial cells that included longitudinal ridges apparently caused by the presence of cytoskeletal structures underlying the plasma membrane which was depressed by the force of the stylus in regions unsupported by cytoskeleton. In recent experiments (16) using lower spring-constant cantilevers (thus reducing the imaging forces), these features were absent unless the force was deliberately increased. It can be concluded that bundles of cytoskeletal filaments form realigned arrays just below the luminal plasma membrane after exposure to flow, resulting in decreased deformability of the surface region. Also contributing to cell-surface rigidity are ankyrin-like and spectrin-like proteins that serve as anchors at the cell membrane for other cytoskeletal proteins (59); it is not known whether these rearrange in response to mechanical forces.

Remuzzi et al. (300) filmed changes in the shape of flow-aligned endothelial cells after removal from flow. Cells remained aligned for several hours followed by periods of rapid relaxation to a polygonal orientation that occurred within discrete regions of the monolayer. Because relaxation was not temporally or spatially uniform, there may be regions of the monolayer where groups of adjacent cells shared mechanical tension. Immunofluorescence micrographs give the impression that stress fibers form a continuum between aligned cells, reinforcing the idea of intercellular tension. The detailed mechanics of these phenomena, which have not been adequately analyzed, deserve further investigation because they define the spatial distribution of intracellular (and possibly intercellular) tension.

During flow, the position of cellular organelles may also change. For example, the Golgi apparatus and microtubule organizing centers have been shown to undergo temporary redistribution (47, 226). The consequences of such rearrangements for cell function are unclear.

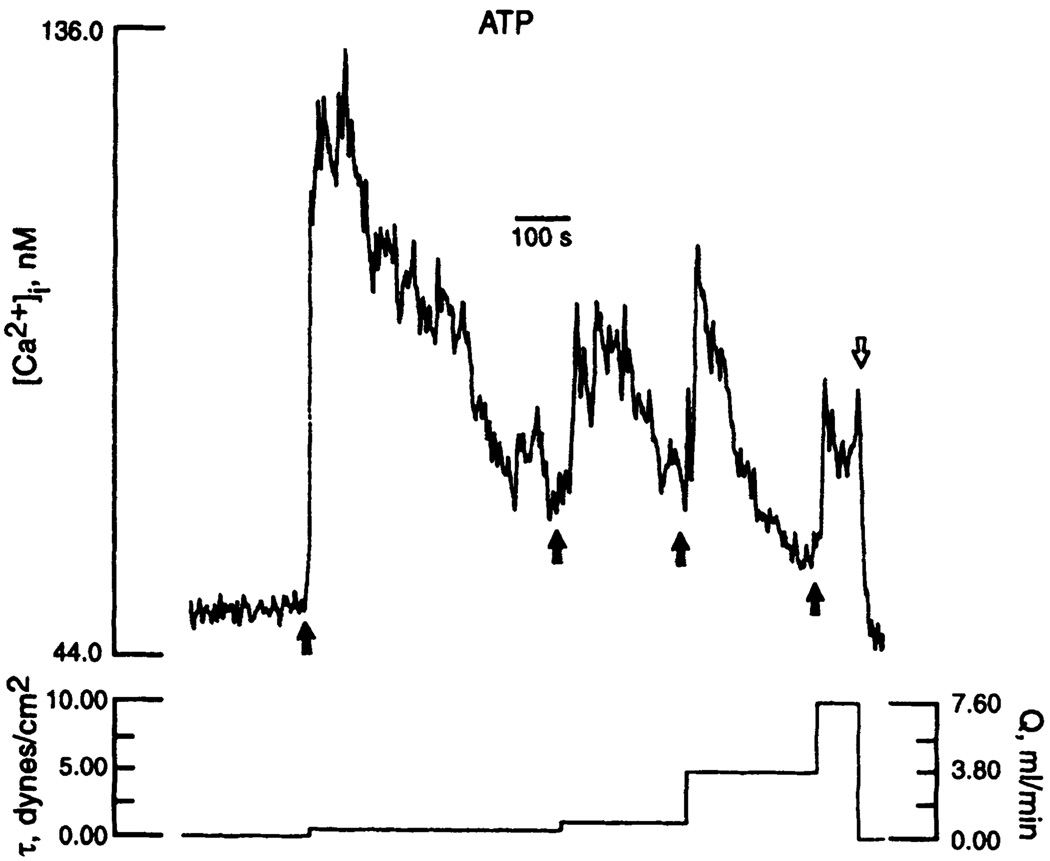

D. Signal Filtering and Adaptation to Mechanical Stimuli

Most information about endothelial mechanotransduction and the wide range of cellular responses that result have been obtained from steady flow experiments in vitro. Endothelial cells in arteries, however, are subjected to hemodynamic forces that might be expected to constantly stimulate the cells. This does not usually happen. For example, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) B chain mRNA, although greatly stimulated in vitro by shear stress, is found at low levels in endothelial cells freshly scraped from an artery (17). Intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) levels appear to be at baseline levels in the endothelium of excised arterioles despite steady flow; when the arteriolar flow rate increases, [Ca2+]i is stimulated (89). Consequently, there must be mechanisms to cope with overstimulation by the normal mechanical environment. Several mechanisms (which are probably interactive) include adaptation and filtering of the signal.

1. Adaptation

Sustained stimulation leads to feedback inhibition of mechanotransduction. Examples include desensitization of shear-sensitive ion channel activity (271), adjustment of cell-surface adenine nucleotide concentrations (82, 83), and intracellular renormalization of calcium levels by activation of calcium pumps to either store calcium in the endoplasmic reticulum or pump it out of the cell (18). One of the first demonstrations of adaptation was a return of flow-stimulated pinocytosis rates to no-flow levels despite the continuation of flow (66). When flow was later stopped, pinocytosis was again transiently stimulated as the cells readapted to no-flow conditions. Cell alignment under flow and its reversal several hours after cessation of flow also represent adaptation and readaptation events (300). Streamlining of the cell surface to reduce the shear stress gradients (15, 16) may be a mechanism of turning off or reducing the force stimulus. Product inhibition of enzyme activities common in ligand-mediated intracellular signaling is another example of adaptation that may also occur in mechanical signaling.

2. Filtering of the signal

When direct mechanical forces stimulate mechanotransduction, the stimulus is coupled to structural components that may act as selective filters responsive only to certain mechanical stimuli. The classic example is the Pacinian corpuscle, which transmits only high-frequency stimuli throughout the structure of the organ (200); manipulation of the structure modifies the frequency response. In a similar fashion, the cytoskeleton may filter hemodynamic stimuli in endothelial cells. The frequency of flow-mediated [Ca2+]i oscillations that have been reported in the presence (340) or absence (133) of agonists may also reflect selective filtration of the force.

Endothelial cells subjected to pulsatile flow fail to respond at certain frequencies. This may be because the positive stimulus for response needs to be sustained. For example, pinocytosis rates that increase with steady shear stress (8 dyn/cm2) were unaffected by 1-Hz oscillations of shear stress around the same mean value (8 ± 5 dyn/cm2) (66). Endothelin-1 mRNA that normally downregulates at 15 dyn/cm2 failed to change when cells were subjected to back-and-forth reversing flow of root-mean-square shear stress magnitude 15 dyn/cm2 but average magnitude of zero (214). Further evidence of differential behavior to oscillatory versus steady flow, and to different types of oscillatory patterns, was reported by Helmlinger et al. (133), who showed that endothelial cells can discriminate between different flow environments. Recently, the same group has reported that the amplitude, delay time, and rise time of [Ca2+]i levels in endothelial monolayers were strongly dependent on the steady and pulsatile characteristics of the flow (133; R. M. Nerem, personal communication). A purely oscillatory flow failed to induce changes of average [Ca2+]i levels, although it resulted in a larger number of cells exhibiting oscillating [Ca2+]i levels.

V. WHERE TRANSMISSION BECOMES TRANSDUCTION: CANDIDATE MECHANOTRANSDUCERS

A. Structural Considerations

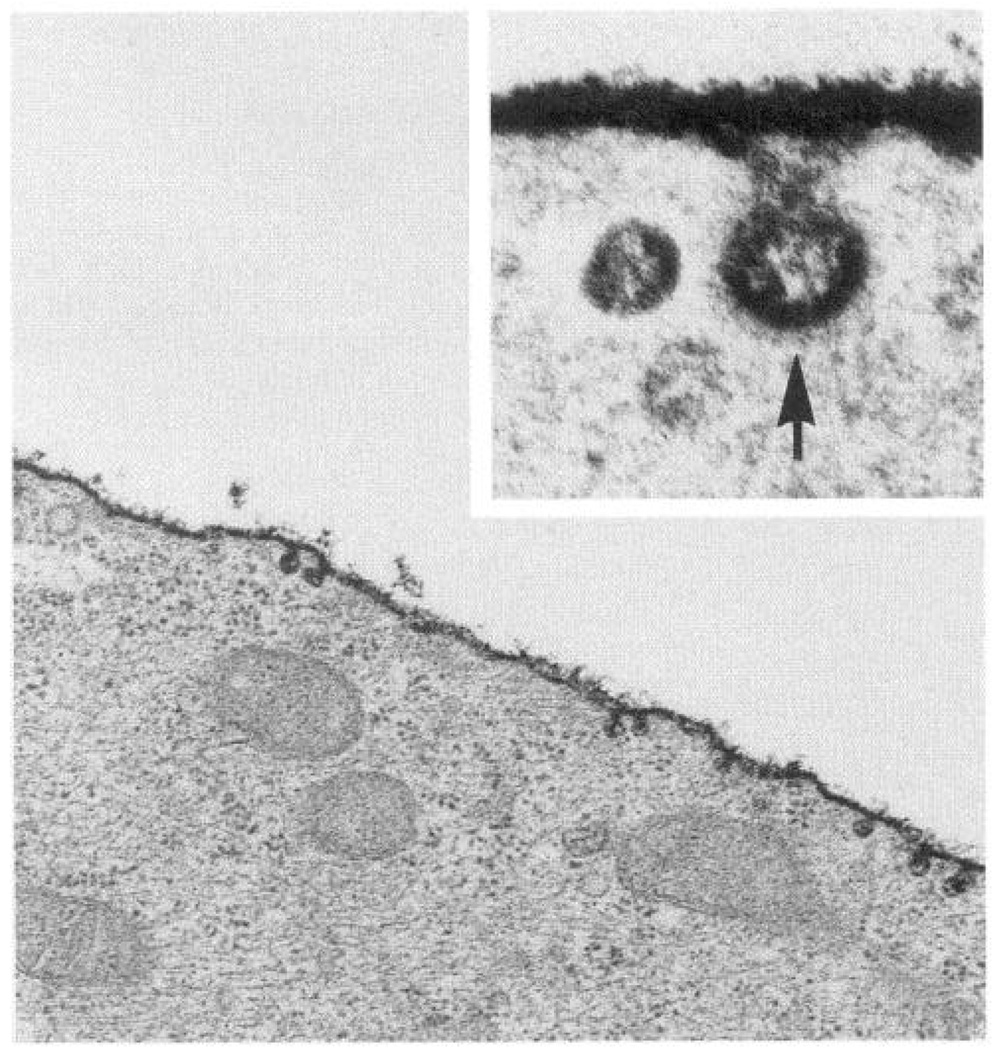

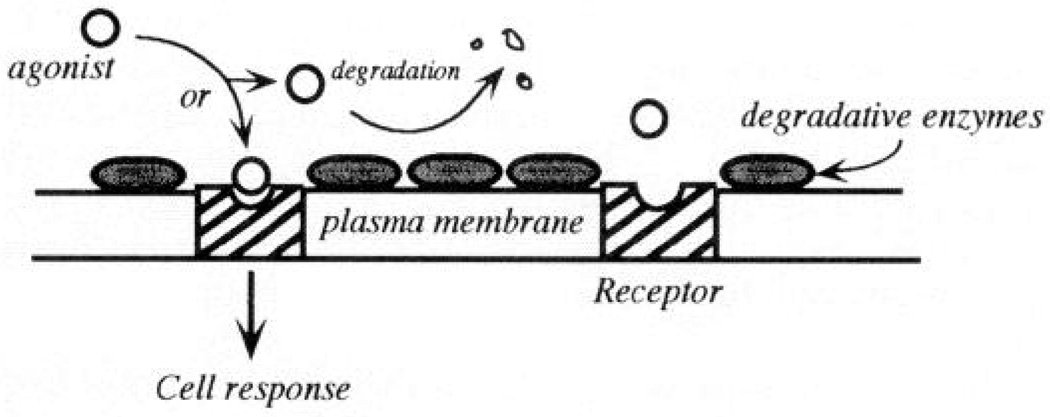

Transfer of fluid shear stress forces to the cell occurs first at the luminal cell surface. Plasma membrane molecules are therefore candidate mechanotransducers that generate intracellular biochemical signals. The cell membrane is heterogeneous in composition and, as demonstrated above, the complex surface geometry results in significant variations of stresses on a subcellular scale. Staining of the cell surface with ruthenium red and similar markers reveals a prominent glycocalyx (Fig. 6), a fringe of carbohydrate-rich glycoproteins, many of which are themselves receptors or are linked to receptors anchored in the plasma membrane (205). The glycocalyx may be a significant structure in mechanotransduction in several ways. First, transmembrane glycoproteins extending into the extracellular space occupied by the glycocalyx may be physically displaced by the frictional hemodynamic shear stress to provoke an intracellular response. Second, the fluid layer associated with the glycocalyx represents a microenvironment for agonist-receptor interactions. It acts as a discontinuous medium between bulk fluid flow and the solid body characteristics of the cell surface. Agonists and chemokines present in the plasma or secreted from the cell are likely to be present in this relatively unstirred layer in quite different concentrations than in the bulk fluid and interact with receptors as a function of flow-related convective and diffusive transport rates (82, 83, 260, 339). This indirect effect of flow on cell signaling, however, is unlikely to occur completely independently of direct mechanical effects and is considered more fully in section VII.

FIG. 6.

Endothelial cell luminal plasma membrane glycocalyx stained with ruthenium red. Inset: invagination of surface at a clathrin-coated pit. Transmission electron microscope magnification: ×40,000; inset, ×175,000.

A prototypic mechanical sensor at the luminal surface may be a molecule or molecular complex whose function is related to its stressed state. Intramolecular forces, defined by structural configuration, set the stress state. The specialized function of a mechanosensor might be expected to be reflected in a specialized structure. This could manifest itself by a particular conformation (e.g., unusually long glycoprotein extensions into the extracellular space; intracellular conformational changes favoring association with soluble second messengers) or by sensitivity to physical displacement of intracellular linkages to cytoskeletal elements. It is suggested therefore that one view of mechanotransduction mechanisms restricts all of the mechanics to the luminal membrane proteins that, once displaced (activated), generate a biochemical cascade(s) at the cytoplasmic face of the membrane. Here the data fit a model of mechanoreceptor activation by stress, the generation of second messengers, and the activation of cytosolic transcription factors that subsequently regulate gene transcription in the nucleus (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

Centralized and decentralized mechanotransduction models in endothelial cells. A: shear stress transduction occurs at a primary site on luminal cell surface after which biochemical/electrophysiological pathways control responses through serial and parallel pathways. B: shear stress transduction occurs at multiple sites that are mechanically coupled by cytoskeleton. Each site, with different sensitivities, response times, and local environment, can generate bioresponses.

The next level of structural complexity in mechanotransduction involves transmission of the stress throughout the cell via the cytoskeleton (refer to Fig. 3). Here the membrane molecules participate in two ways: 1) to passively transfer the stress to the cytoskeleton in one part of the cell and 2) to respond to cytoskeletal deformations at sites remote from the stimulus. The latter may occur at any site of connection between membrane proteins and cytoskeleton including the luminal cell surface (383), intercellular junctions (361), abluminal focal attachment sites (35), and the nuclear membrane (286). Because a reasonable case can be made that these sites are mechanically connected, [for example, nuclear shape depends on cell adhesion events that are mediated through integrin-adhesion protein interactions (155, 154)], mechanotransduction mechanisms may be decentralized. This scenario is consistent with multiple pathways of biochemical responses that lead to quite different end results in the cell. Rather than a serial hierarchy of responses emanating from a primary mechanotransducer, decentralization will allow several mechanisms to respond to a variety of stress configurations (Fig. 7B). For example, the ionic conductance of Ca2+ and Na+ in muscle cell membrane changes as cytoskeletal strain is changed. The resulting depolarization opens voltage-dependent potassium channels that initiate repolarization (150), thereby contributing to reversal of the response and the setting of a new mechanical threshold (121); similar mechanisms are applicable to stretch and shear stress-activated ion channels in endothelial cells (see below). The “decentralized mechanism” (Fig. 7B) more readily accommodates temporal differences in responses and a greater diversity of end responses.

Wherever mechanotransduction occurs, the process is likely to be modulated by changes in the stiffness of a receptor(s), the stiffness of the mechanical coupling between the receptor and other structures such as the cytoskeleton, the stiffness of the cytoskeleton itself, and the integrated structure and geometry of the tissue including its association with the extracellular matrix.

Although from structural studies it is obvious that the cytoskeleton interacts mechanically with the plasma membrane, it is only recently that stress transmission to the cytoskeleton via transmembrane proteins has been directly demonstrated. Using ferromagnetic microbeads coated with adhesion peptides or antibodies to integral membrane proteins (integrins), Wang et al. (383) were able to measure the mechanical resistance to deformation of the endothelial cytoskeleton when the beads were twisted in a magnetic field. They noted that the resistance to twisting was a function of the bead/membrane association and the integrity of the cytoskeleton. Only when beads were coated with integrin ligands was a significant mechanical connection maintained. Disruption of the actin microfilaments by cytochalasin D greatly suppressed the stiffening response; disruption of other cytoskeletal components added to the suppression. The studies were directed primarily at β1-integrin, a common member of the β-subunit integrin family (151). They concluded that β1-integrin can act as a cell-surface mechanoresponsive element that can transfer mechanical forces across the cell surface via a specific molecular pathway to the actin stress fibers. This conclusion is likely to be applicable to all integrin-rich regions of the cell where cytoskeletal structures connect with the membrane proteins. Tension and compression in the cytoskeleton of other cells have been directly measured (75). Stress distribution to the cell junctions, focal adhesion sites, and nuclear membrane of endothelial cells subjected to flow is consistent with these models.

The distribution of stress throughout the cell via an integrated structural network might be explained in part by the tensegrity model of tension as developed for cellular structures by Ingber and co-workers (156–158). A notable finding of Wang et al. (383) was that cytoskeletal stiffness increased linearly with the applied stress, a property often noted in living cells (228, 287) and less commonly found in synthetic inert materials. The tensegrity model requires continuous tension to maintain an array of interconnected rigid structures. When tension is changed, the components rearrange to new positions, a response that depends less on the individual components than on the integrated structure. Linear cellular responses to altered stress fit this model well, as does the redistribution of tension to a variety of putative mechanotransduction sites in the cell. While tensegrity is unlikely to provide a complete explanation of flow-related stress transmission in the endothelium (e.g., compression elements may play some role in cytoskeletal mechanics; metabolic regulation undoubtedly is involved), it is a useful model for considerations of cellular mechanotransmission and transduction mechanisms.

B. Plasma Membrane Proteins as Mechanoreceptors

If there are proteins at the endothelial surface that function as mechanotransducers, what characteristics might be required to fulfill such a function? The receptors would be located at a site where either the stress acts directly or to which the stress can be efficiently transmitted. The efficiency of signaling across the membrane to the interior of the cell would be improved if the receptor is a transmembrane protein with significant cytoplasmic sequence perhaps arranged in loops and/or a long tail. Its activity would ideally be associated with a well-defined intracellular signaling pathway(s).

Receptor families that meet these criteria include ion channels, integrins, G protein-linked receptors, and mitogen-activated receptors. The last two groups include several receptors for agonists whose secretion from endothelial cells is stimulated by flow (purinoceptors, neurotransmitter receptors, and growth factor receptors).

C. Mechanosensitive Ion Channels

Endothelial cells and their cell membranes exhibit certain ion channel responses to mechanical forces that appear to be identical to those identified in simpler life forms (222, 318). Other ionic responses, however, are endothelial specific (271). Change of intracellular ion concentrations, particularly calcium and potassium, are implicated in many of the second messenger pathways and in gene regulatory changes discussed in this review. Cationpermeable channels of varying degrees of selectivity have been demonstrated in cultured endothelial cells (2, 61, 136, 190, 269, 270).

Mechanically activated potassium-specific, calcium-specific, and nonspecific cation channel activities are present in cultured endothelial cells. Some interactions between them are mediated by the consequences of their opening (2, 136). For example, potassium channel activation usually leads to a shift in the membrane potential (Vm) toward the reversal potential for potassium, resulting in cellular hyperpolarization that may influence the activity of other channels in the cell. Although voltage-gated calcium channels appear not to be present in cultured endothelial cells (2, 271, 360), hyperpolarization can lead to increased calcium influx via a calcium/phosphatidylinositol/hyperpolarization-activated calcium-permeable channel (202, 204, 270), and hyperpolarization increases the electrochemical gradient for calcium, resulting in calcium influx (136). The opposite effect, depolarization, attenuates cellular functions that rely on calcium influx, e.g., nitric oxide (NO) release and vasodilation (43, 203). The different vectors inherent in hemodynamic forces, pressure, and shear stress also appear to selectively activate ion channels. Thus there are common stretch-activated nonspecific cation channels in endothelial cells (190) that contrast with shear stress-activated potassium channel activity (271). Such cell activities can have opposite consequences for the Vm of the cell, which in turn will influence downstream signaling pathways (61). Presumably, in vivo there will be a differential exposure to the components of blood flow forces such that one or more of these pathways will dominate, depending on the local hemodynamic conditions. An important consideration regarding shear stress-activated channel activity is whether the ion channels are activated downstream from some other kind of mechanical receptor or whether there may be direct alteration of the conformation of the proteins comprising the ion channels to allow increased ion permeability.

Levitan (195) proposed ion channel phosphorylation some years ago. Recently, Olesen and Bundgaard (270) have demonstrated that an inward rectifying potassium channel in bovine aortic endothelial cells requires phosphorylation to remain open. Inside-out patches required administration of ATP to the cytosolic side to maintain ion channel activity. These findings suggest that a prominent inward rectifying potassium channel in endothelial cells has some similar characteristics to the rat kidney channel cloned by Ho et al. (137) and for which a putative ATP binding site impli ated in phosphorylation was identified. However, attempts to clone endothelial potassium channels on the basis of structural homology have been unsuccessful to date.

1. Shear stress-activated potassium channels in endothelial cells

These were first identified by Olesen et al. (271) using whole cell recordings of bovine aortic endothelial cells grown in microcapillary flow tubes. When flow was imposed, a membrane current developed as a function of shear stress with half-maximal activation of 0.7 dyn/cm2. Channel activity reached a plateau near 20 dyn/cm2. On the basis of ion selectivity and reversal potential, the current was identified as an inward rectifying potassium current and was designated IKS. The current was rapidly activated in response to flow, did not rapidly desensitize, and was inactivated when flow was stopped. Recently, single-channel recordings in the cell-attached mode have demonstrated activation of an inward rectifying potassium channel that often demonstrated a delayed opening and closing response to shear stress (163). Because the single channels were not directly exposed to the shear stress (being protected by the micropipette), these preliminary findings suggest that the channel is activated secondarily to other signaling events initiated by shear stress elsewhere on the same cell and transmitted to the channels in the micropipette.

The IKS activity, which was blocked by Ba2+ and Cs+, resulted in hyperpolarization of the endothelial cell. Neither atrial myocytes nor vascular smooth muscle cells expressed IKS, suggesting some degree of endothelial specificity. Endothelial hyperpolarization as a function of shear stress was also reported using membrane potential-sensitive fluorescent dyes (250). Furthermore, studies of unidirectional Rb+ efflux by Alevriadou et al. (6) have confirmed a shear stress-dependent plasma membrane permeability to K+. Cooke and co-workers (51, 265) using pharmacological inhibitors have demonstrated the association of flow-sensitive endothelial potassium channel activity with the release of an endogenous nitrovasodilator in arterial rings. They have also provided circumstantial evidence that activation of a potassium channel is associated with G protein coupling and the elevation of endothelial guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP). Again, however, it is unclear whether the potassium channel activity is secondary to upstream mechanoreceptors. The potassium channel blockers tetraethylammonium and Ba2+ inhibit IKS and shear-induced downregulation of endothelin-1 mRNA expression (A. Malek, personal communication). Because chelation of [Ca2+]i also inhibits endothelin downregulation, the potassium channel blockers, by preventing hyperpolarization, may inhibit calcium influx.

A link between cyclic nucleotides and potassium channels that may be of general relevance was recently reported (330). Adenylyl cyclase isolated from Paramecium flagellum was reconstituted in a lipid bilayer. The enzyme acted as a potassium channel in which the hyper-polarized state of the enzyme regulated adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) production. Thus ion flux and generation of an important biochemical second messenger were regulated by an enzyme that exhibited some of the characteristics of an ion channel.

2. Stretch-activated ion channels

This kind of mechanotransducing ion channel has been demonstrated in a wide variety of cells ranging from primitive organisms to mammalian cells (see review by Sachs, Ref. 318). For example, stretch-activated ion channels have been found in snail neurons (244), skeletal muscle (122), ventricular cells (55), renal tubular epithelium (319), choroid plexus epithelium (45), and vascular endothelial cells (190).

When a micropipette is applied to the cell surface and attached to the cell membrane by suction to form a tight seal, distension of the membrane patch captured in the pipette can be controlled by negative pressure. With the use of such an approach, the degree of stretch has been found to be related to the electrical activity of the membrane and, more specifically, to the opening of transmembrane cation channels. In vascular endothelial cells, Lansman et al. (190) first described mechanosensitive ion channels in membrane patches. During suction pulses of 1–20 mmHg pressure in a cell-attached patch-clamp configuration, single-channel data were collected. The stretch-sensitive channels were cation specific, with a conductance of ~40 pS with both fast and slow components to their opening. A principal consequence of the activation of these channels is the influx of calcium, resulting in depolarization of the cell. The resulting influx of calcium would also be expected to have profound effects on many of the bioresponses to hemodynamic forces as outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Shear stress and related mechanical stress responses in endothelial cells (arranged in order of response time)

| Effect | Force | Cell Type and Response Time |

Significance | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K+ channel activation, hyperpolarization (Whole cell recording) |

LSS; 0.2–16.5 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; s | Related to vasorelaxation | 51, 163, 271 |

| Rb+ efflux stimulated | LSS, 1–10 dyn/cm2 | PAEC | Graded transient increase of K+ permeability |

6 |

| Hyperpolarization (Vm-sensitive dyes) | LSS; 10–120 dyn/cm2 | BPAEC; steady state at 60 s |

As above | 250 |

| Activation of nonselective cation channels (membrane patch) |

Suction (pressure, stretch); 10–20 mmHg |

PAEC; ms | Endothelial stretch-activated channels |

190 |

| Intracellular Ca2+ rise (fluo 3) | Mechanical poking and dimpling |

HUVEC; s | Stretch-activated Ca2+ channels; depolarization. |

115 |

| Large increase in release of NO | LSS; 8 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; s | Flow-mediated vasorelaxation |

51, 96, 258, 262, 364, 375, 376 |

| Release of ATP, acetylcholine, endothelin, and substance P |

Flow through microcarrier bed | HUVEC; s | Neurotransmitter release | 26, 27, 237, 294 |

| Stimulation of PA and PE hydrolysis | LSS; 1.4 and 22 dyn/cm2 | HUVEC; 10–30 s | Additional sources of AA; implies activation of PLA2 |

22 |

| Decrease of intracellular pH | LSS; 0.5–13.4 dyn/cm2 | BAEC | Modulation of ionic balance | 406 |

| Transient elevation of IP3; biphasic (BAEC) |

LSS; 30 and 60 dyn/cm2; cyclic stretch |

BAEC, HUVEC; >15– 30 s; major peak at 5 min (BAEC) |

Phosphoinositides as second messenger for shear stress transduction |

20, 22, 260 |

| Intracellular Ca2+ rise; Ca2+ oscillations |

LSS; 0.2–4.0 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 15–40 s | Ca2+ as second messenger | 7, 106, 332, 339 |

| Flow modulation of effects of vasoactive agonists ATP and bradykinin |

LSS; 0–30 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; s | Indirect stimulation via agonist receptor mechanisms |

82, 83, 239, 261, 341 |

| cGMP increased 3-fold via a NO- dependent mechanism; endothelial K+ channel implicated |

LSS; 0–40 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 60 s | Vasoregulation mechanisms | 264 |

| Transient elevation of IP3 | Cyclic strain; 24% deformation; 1 Hz |

HSVEC | Phosphoinositides as second messengers for strain deformation |

293, 310 |

| Sustained PGI2 release; G proteins implicated |

LSS; 0–9 and 14.0 dyn/cm2 | HUVEC; 2 min | PGI2 regulation of vascular tone | 19, 95 |

| Pulsed PGI2 release at higher level than steady flow |

LSS (pulsatile); mean 10 dyn/ cm2 |

HUVEC; <1 min | Antithrombotic properties | 118 |

| Augmented factor Xa production (indicative of enhanced tissue factor activity) |

LSS; 0.7 and 2.7 dyn/cm2 | Activated HUVEC; min |

Enhanced procoagulant activity | 119 |

| Vascular free radical generation | Perfusion rates 2–12 ml/min | Ex vivo artery; 10 min |

Unknown | 191 |

| Stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK); 35 dyn/ cm2 peak |

LSS; 3.5–117 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 5 min, peak 20–30 min |

Involvement of membrane mitogen receptor-like pathway in shear transduction |

B. Berk, personal communication |

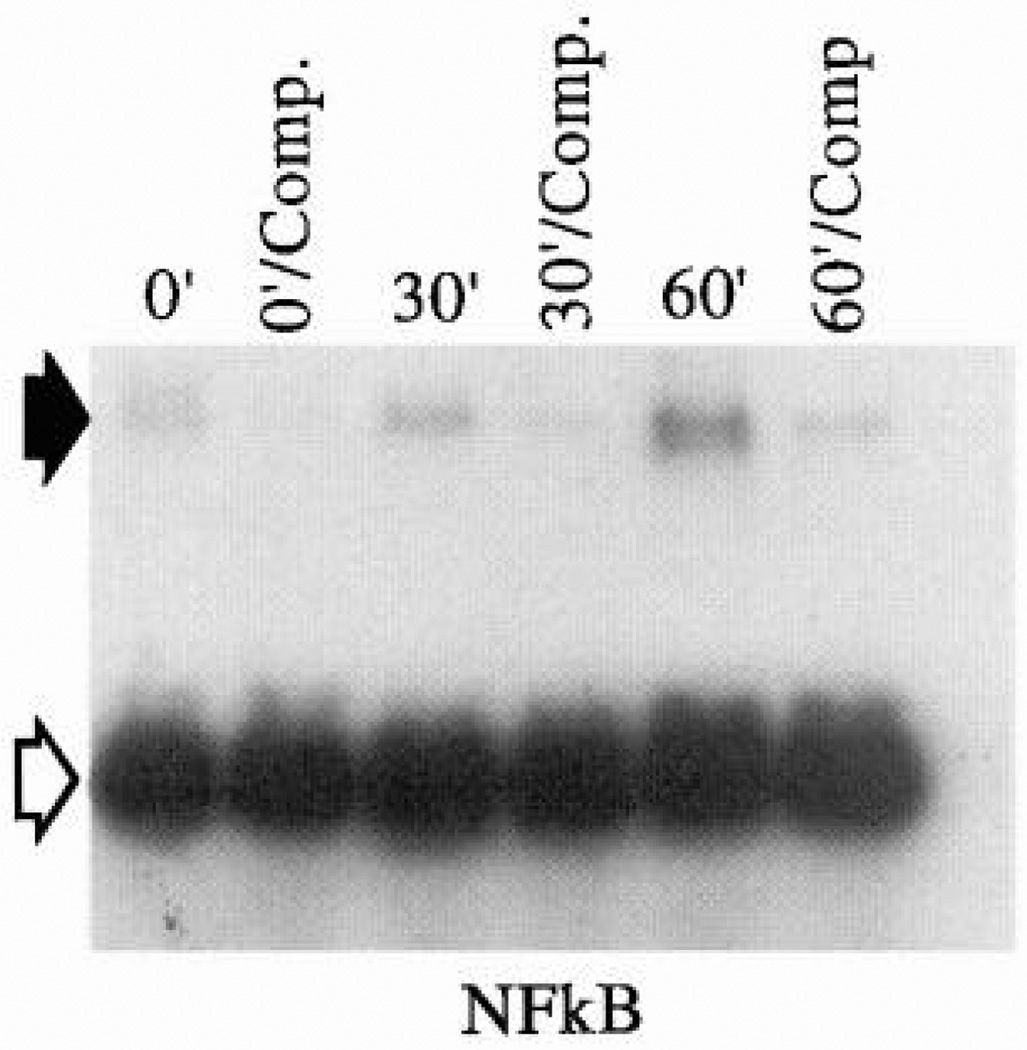

| Activation of NFκB | LSS; 10 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 20 min | Transcription factor activation | 186, 301 |

| Induction of c-myc, jun | LSS; 10 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 30 min | Immediate early growth response genes |

146, 186 |

| Activation of adenylyl cyclase | Cyclic stretching; osmotic swelling |

BAEC, HUVEC; min | cAMP as second messenger for stretch |

192, 385 |

| Directional remodeling of focal adhesion sites; Realignment with flow (>8 h) |

LSS; 10 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; min, h | Cell attachment site involvement in transmission and/or transduction of stress |

68, 304 |

| Tension controls cell shape, pH, and growth via extracellular matrix- integrin binding |

Modulation of inherent cell tension |

Capillary EC; <1 h | Integrins regulate cell growth via cell tension |

156 |

| Downregulation of VCAM-1 expression |

LSS; 0–7.2 dyn/cm2 | Mouse lymph node endothelial cells; >1 h |

Preferential leukocyte adhesion at low shear stress |

266, 321 |

| 10-Fold enhancement of PDGF-A mRNA; PDGF-A peak at 1.5–2 h |

LSS; 0–51 dyn/cm2 | HUVEC, BAEC; >1 h | Enhanced mitogen secretion; regulation of SMC growth |

147, 216, 238 |

| 2- to 3-fold increase of PDGF-B mRNA followed by 4-fold decrease by 9 h; PKC dependence controversial |

LSS; 10–36 dyn/cm2 steady, pulsatile, turbulent |

HUVEC, BAEC; 1–9 h | Identification of shear stress response element of PDGF-B gene |

147, 238, 301 |

| bFGF mRNA stimulated 1.5- to 5-fold | LSS; 15 and 36 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 0.5–9 h, peak at 6 h |

Peptide growth factor regulation |

216 |

| Pinocytosis stimulated; adaptation by 6 h |

LSS; >5 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; <2 h | Plasma membrane vesicle formation rate transiently elevated |

61 |

| Induction of c-fos; 50% block by PKC inhibitor |

LSS; 4–25 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 1–2 h | Early growth response gene | 146, 148, 295 |

| Increased TGF-β1 mRNA and biologically active TGF protein |

LSS; 20 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 2 h | Inhibition of smooth muscle growth |

265 |

| Upregulation of ICAM-1 mRNA and protein and enhanced lymphocyte adhesion; downregulated by 6 h |

LSS; 2.5–46 dyn/cm2 | HUVEC; 2 h | Enhanced binding of LFA-1- positive cells |

249, 321 |

| Stimulation of IL-6 secretion and gene expression |

LSS; >10 dyn/cm2 | HUVEC; 2 h | Cytokine secretion | 223 |

| Redistribution of Golgi apparatus and MTOC to upstream location in cell; normalized by 24 h |

LSS; 22 and 88 dyn/cm2 | BCAEC; >2 h | Temporary displacement of organelles |

47 |

| Induction of protein kinase C | LSS; >10 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; <3 h | Regulation of protein phosphorylation |

181 |

| Endothelin mRNA and protein secretion reported to be both stimulated and downregulated; mechanism appears to involve filamentous actin and microtubules |

LSS; 5–20 dyn/cm2 | PAEC and BAEC; peak at 2–6 h |

Regulation of vasoconstriction |

214, 215, 243, 338, 398 |

| NO synthase mRNA and protein stimulated |

LSS; 15 dyn/cm2; flow through microcarrier bed; 0.5–2.0 ml/min |

BAEC; 3 h | Vasorelaxation |

182, 258, 285, 375, 376 |

| HSP 70 mRNA increased 2- to 4-fold | LSS; bidirectional | BAEC; 4 h | HSP 70 shock response to flow | 139 |

| tPA mRNA expression and secretion stimulated |

LSS; 15 and 25 dyn/cm2 | HUVEC; 5 h | Enhancement of fibrinolytic activity |

79–81 |

| Cell proliferation in quiescent monolayer |

Turbulent flow; average shear stress 1.5–15.0 dyn/cm2 |

BAEC; >3 h | Loss of contact inhibition of growth by disturbed flow |

63 |

| Cell alignment in direction of flow; function of time and magnitude of shear stress |

LSS; >5 dyn/cm2 | All types; >6 h | Minimizes drag on cell |

78, 85, 187, 193, 194 |

| F-actin cytoskeletal and fibronectin rearrangement |

LSS; >5 dyn/cm2 and in vivo | All types; >6 h | Associated with cell realignment |

78, 97, 169, 189, 274, 388, 389 |

| Differential cell shape and alignment responses; corresponding F-actin changes |

LSS; pulsatile 1 Hz; sinusoidal flows of various patterns up to 60 dyn/cm2 |

BAEC; >6 h | Discrimination between different types of pulsatile flows |

133, 134, 254, 255 |

| Cell realignment perpendicular to strain; protein synthesis increased; F-actin redistribution perpendicular to strain |

Cyclic biaxial deformation; 0.78–12%; 1-Hz frequency 20–24% strain; 0.9–1.0 Hz |

BPAEC; >7 h HUVEC, HSVEC; 15 min |

Stretching of artery by blood pulsation; separation of strain and shear stress effects |

152, 343, 358 |

| Histamine release and histamine decarboxylase activity stimulated |

Oscillatory LSS; range, 1.6–8.2 dyn/cm2 |

BAEC; >6 h | Modulation of endothelial permeability barrier |

348 |

| Decreased thrombomodulin mRNA and protein at 15 and 36 dyn/cm2 |

LSS; 4, 15, and 36 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 9 h | Protective role against thrombosis in regions of low shear stress |

217 |

| Increased thrombomodulin activity (synthesis of activated protein C) |

LSS; 25 dyn/cm2 | HUVEC; 24 h | Protective in regions of higher shear stress |

321 |

| Downregulation of fibronectin synthesis |

LSS; 24 dyn/cm2 + 20 mmHg hydrostatic pressure |

HUVEC; 12 and 48 h | Altered cell adhesion; platelet- endothelial interactions |

124 |

| Regional cell cycle stimulation in confluent monolayer |

Disturbed laminar flow (flow separation, vortex, reattachment); 0–10 dyn/cm2 |

BAEC; 12 h | Steep shear gradients stimulate cell turnover; focal hemodynamic effects |

76 |

| Reorganized topography of luminal surface at subcellular resolution |

LSS; 12 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 24 h | Reduced gradients of shear stress in aligned cells; force transmission altered |

15, 16, 395 |

| Mechanical stiffness of cell surface proportional to extent of realignment to flow |

LSS; 10–85 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 24 h | Decreased deformability of subplasma membrane cortical complex |

323 |

| LDL metabolism stimulated | LSS; 30 and 60 dyn/cm2 | BAEC; 24 h | Endothelial cholesterol balance | 351 |

| Increase in class I and induction of class II MHC antigen expression |

LSS; 3–36 dyn/cm2 | Fat, omentum, and brain microvessels; 24–36 h |

Role of flow in immune response |

221 |

| Inhibition of endothelial cell division | LSS | BAEC; 24–48 h | Regulation of endothelial regeneration |

407 |

| Inhibition of collagen synthesis and stimulation of cell growth |

Cyclic biaxial stretch; 3 cycles/ min; 24% deformation |

BAEC, myocytes; 5 days |

Inverse relationship related to endothelial repair mechanisms |

359 |

LSS, laminar shear stress; BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cells; Vm, membrane potential; BPAEC, bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells; PAEC, porcine aortic endothelial cells; BCAEC, bovine carotid artery endothelial cells; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cells; PGI2, prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin); tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; NO, nitric oxide; AA, arachidonic acid; PLA2, phospholipase A2; PDGF-A, PDGF-B, platelet-derived growth factor A and B chains, respectively; SMC, vascular smooth muscle cells; HSVEC, human saphenous vein endothelial cells; MTOC, microtubule organizing center; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; HSP 70, 70-kDa heat-shock protein.

The mechanisms by which mechanical forces may control stretch-activated ion channel gating are largely unknown; the little information available has been conducted on nonvascular cells (318). Open probability increases exponentially with the square of differential pressure across the membrane (122). It appears unlikely that the lipid bilayer significantly transmits force to the channel to open it because of limitations in the area of bilayer required to do so (318). Consequently, it seems more likely that the underlying cytoskeleton in some way is connected to the ion channels such that when membrane is captured in a pipette and distended, the cortical cytoskeleton is also stretched; this in turn activates the channel. This may be a very local event because both cell-attached patches and isolated inside-out patches demonstrate similar stretch sensitivity, suggesting that an intact cytoskeleton throughout the cell is not required (122). Sachs (318) has calculated the distribution of these channels to be ~3/µm2 of membrane surface area and has proposed a model in which the channels are located at the nodes of a network of submembranous cytoskeletal elements. A short delay after the application of stretch before the channel opens also suggests an elastic component involved in directing tension to the channel, and treatment with drugs that disrupt the cytoskeleton clearly shift the open probability curve toward lower pressures. Together, these observations suggest that intrinsic cell tension and its alteration by externally loaded forces play a key role in the regulation of these channels.

Variations of stretch-sensitive channels include mechanosensitive potassium ions in the renal medulla that are calcium activated (364). They appear to be involved in osmotic swelling and volume regulation. Other variations found in nonvascular cells include stretch inactivated potassium-selective channels side by side with potassium-selective stretch-activated channels in snail neurons (244). Their activation will antagonize the effects of stretch-activated channels in the same cell and presumably impart a finer regulation of potassium permeability at intermediate membrane tensions. They have not yet been reported in higher animals.

The physiological significance of diverse channel sensitivity to stretch and shear stress in endothelial cells may be related to the high variability of hemodynamic forces in the arterial circulation. In regions of complex disturbed laminar flow, where shear stresses and pressures vary over short distances and throughout the cardiac cycle (60), shear stretch and stress may activate synergistic or antagonistic effects mediated through ion channels. Corresponding regional hyperpolarization/depolarization responses may regulate local tone at such sites (61).

Recently, inward rectifying potassium channels have been cloned from heart and kidney tissues to reveal structures that are quite different from voltage-gated potassium channels (137, 179). Attempts to clone the endothelial counterparts of such channels by sequence homology, however, have yet to prove fruitful (M. Volin, L. Joseph, and P. F. Davies, unpublished data; G. Droogmans, personal communication). Because prominent inward rectifying potassium channel activity is clearly present in endothelial cells as observed by electrophysiological recordings, it seems likely that these channels express unique characteristics.

The mechanism of potassium channel activation by shear stress could be 1) direct displacement of the channel proteins or 2) secondary to a mechanoreceptor and second messengers specific for the channels. The latter explanation would be consistent with similar hyperpolarizing responses to a variety of vasodilatory agonists originating from platelets or erythrocytes in the blood (ATP, ADP, 5-hydroxytryptamine) (145) and from the endothelium itself (acetylcholine, ATP, substance P, histamine, endothelin, arginine vasopressin, bradykinin, angiotensin II) (26, 27, 37, 168, 197, 199, 237). It should be noted, however, that unlike these agonist-receptor interactions, shear stress does not always lead to increased [Ca2+]i, as discussed in section VIII.

D. Focal Adhesions and Integrins as Mechanotransducers

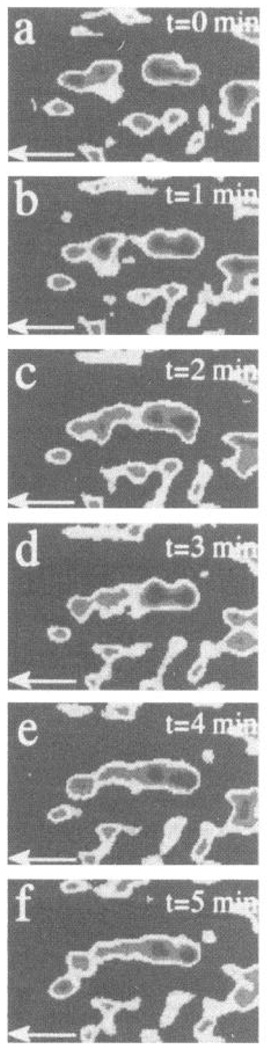

Focal adhesions are regions of the abluminal cell surface where membrane components contact the extracellular matrix (35, 161, 278, 369). They are the sites primarily responsible for cell adhesion and are involved in the regulation of endothelial cell signaling, morphology, proliferation, migration, and differentiation (117, 130, 132, 155, 159, 154, 180, 210, 213, 292, 309, 331, 399, 400). They provide anchorage essential for the maintenance of tension within the cell (hence cell shape) by the association of actin stress fibers on the cytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane with an array of cytoplasmic proteins that link the cytoskeleton to transmembrane integrins (5, 32, 35, 131, 379). This provides a continuum between the intracellular cytoskeleton and extracellular adhesion proteins to which the integrins are bound (73, 87, 144, 247, 276). Focal adhesions are the most intensively studied of the possible cytoskeletal-linked mechanotransduction sites to which cell tension is transmitted by flow. Until several years ago, the sites were regarded as relatively inert, (105, 354, 370). However, work over the past 7 years has identified focal adhesions as sites of concentrated activity of protein kinase homologues of viral oncogenes (142, 143, 371–374) and protein kinase C (372) and implicated them in cell signaling (87). In endothelial cells, the link between focal adhesions and mechanotransduction became apparent when it was demonstrated that shear stress applied to the luminal surface of cultured bovine endothelial cells or human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) resulted in directional remodeling of the abluminal focal adhesion sites (69, 70, 304). This was observed directly in living cells using tandem scanning confocal microscopy (Fig. 8), a technique that when combined with digitized image analysis provides quantitative information about the dynamics of membrane-substratum interactions (69). Endothelial focal adhesion sites undergo rapid remodeling even in quiescent cells within the confluent monolayer, but the direction of extension and retraction of membrane contact is random. During flow (10-dyn/cm2 unidirectional shear stress), however, periods of directional remodeling occurred that were sometimes immediate, often delayed, and led to the alignment of focal adhesions in the direction of flow together with fusion of smaller contact regions to form a reduced number of larger adhesion sites (Fig. 9). Girard and Nerem (111) also observed directional redistribution of proteins associated with focal adhesion sites including vinculin and integrins. The cytosolic proteins focal adhesion kinase (p125FAK), tensin, and paxillin, all enriched at focal adhesions, show similar alignment (unpublished data). The area of membrane/substratum contact does not vary greatly through out the remodeling process, and calculations of cell adhesion from measurements of contact area and separation distance between membrane and substratum showed adhesion to be constant despite the dynamic characteristics of the remodeling process (69, 71). These studies demonstrate little change in adhesion as defined by the physical proximity of membrane and substratum; however, they did not directly address the attachment strength of the focal adhesions (although there is good correlation between focal adhesion area and centrifugal force required to detach cells).

FIG. 8.

Endothelial abluminal cell surface geometry observed in real time by tandem scanning confocal microscopy after image processing (Quantex QX-7) and computer enhancement (Silicon Graphics Indigo II, IDL software). Membrane is organized into focal adhesion sites that extend downward to (invisible) substratum. Because this is a perspective view, scale marker refers to center of image only. (Courtesy of A. Robotewskyj and Dr. M. L. Griem, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.)

FIG. 9.

Tandem scanning confocal microscopy of endothelial cell focal adhesion site rearrangement during flow. Detailed real-time images 1 min apart of reorganizing focal contacts in a cell within a confluent monolayer during flow. Width of field is 2.5 µm. Progressive fusion and alignment of regions occurred over a short interval. Note that small area to left of newly forming aligned site did not significantly change, whereas other sites, above and below, migrated in direction of flow (shown by arrow). Cell boundaries did not significantly change during this period. [From Davies et al. (70). Reproduced from The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1993, vol. 91, p. 2640–2652 by copyright permission of The Society for Clinical Investigation.]

The cytoskeletal events that may alter the structure of attachment sites and hence change their strength have been recently investigated by Ward and Hammer (384). They modeled focal adhesions as integrin clusters, linked to the cytoskeleton, that bind extracellular adhesion proteins. The extent of adhesive strengthening when focal adhesions assemble depends on the elastic rigidity of the cytoskeletal connections. They concluded from theoretical and experimental calculations that rigid cytoskeletal connections favor much greater attachment strengths. This conclusion is also consistent with decreased membrane deformability (323) and increased resistance to detachment when endothelial cells have aligned with the flow, although streamlining of the luminal surface (15) will decrease the effective shear stress and also favor attachment.

Another quantitative aspect accessible from image analysis is the rate of remodeling, defined as the two-dimensional focal adhesion area gained and lost per unit time. Equivalent rates were measured whether flow was present or not (70). Thus, during flow, only the direction of the remodeling event was different, not the quantity of remodeling. In contrast, however, the rate of remodeling was markedly changed when the composition of the extracellular adhesion proteins was modified; this presumably is mediated through different integrins. These studies demonstrated that focal adhesions are dynamic structures, an observation consistent with their signaling function, and that frictional shear stress at the luminal endothelial surface is transmitted to the abluminal focal adhesion sites via the cytoskeleton.

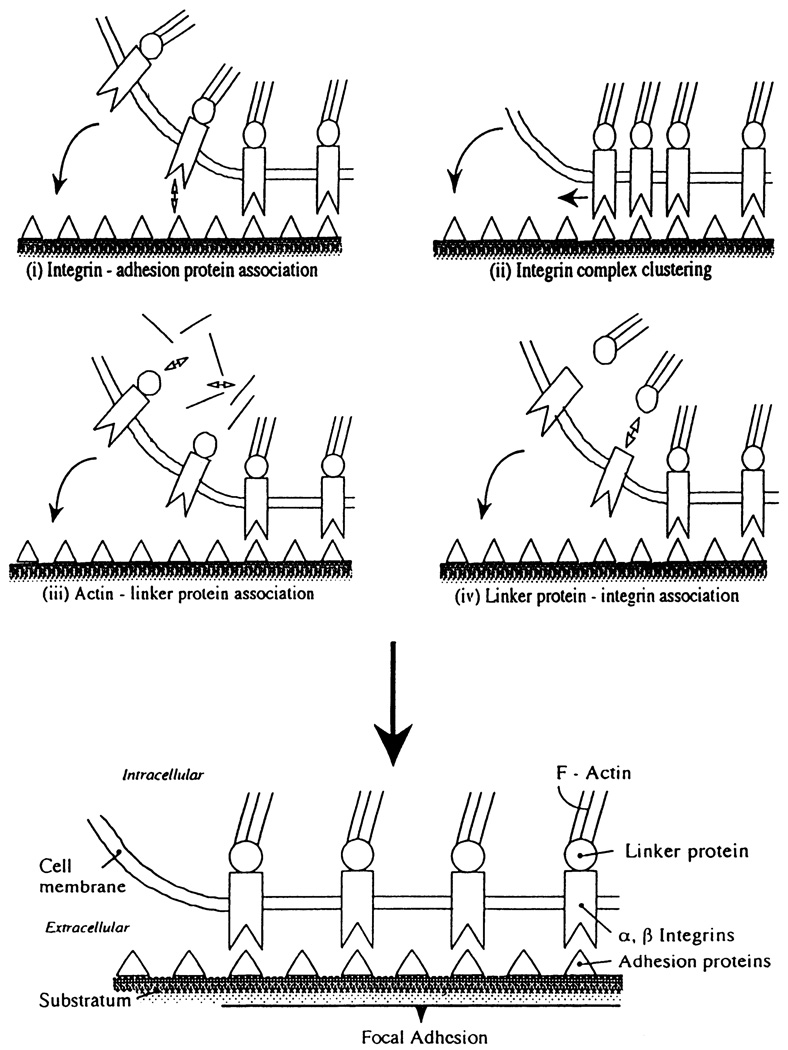

The molecular mechanisms responsible for focal adhesion remodeling are unclear. Transmembrane integrins bind adhesion molecules of the extracellular matrix on the outside and connect to the cytoskeleton via linker proteins on the inside. During remodeling, cell membrane must approach close enough (10–15 nm) to the substratum to form new focal adhesion area, a process that may involve changes of integrin-adhesion protein association, lateral migration of existing integrin-adhesion protein complexes, and/or association of cytoskeletal elements and integrins with linker proteins to establish structural continuity from inside to outside the cell (Fig. 10). The most relevant integrins in endothelial cells appear to be the fibronectin receptors α5β1 and αvβ1, laminin receptor α6β1, vitronectin receptors αvβ3 and αvβ5, and the basement membrane receptor α6β4 (44, 171). As a consequence of integrin specificity for different adhesion proteins, the composition of the extracellular matrix influences focal adhesion remodeling rates (70) and endothelial adhesion (328) during flow.

FIG. 10.

Mechanisms of focal adhesion formation/remodeling. Changes in affinities of principal proteins include those between integrins and adhesion proteins (i); between cytoskeleton and linker proteins such as talin, vinculin, tensin, paxillin, p125FAK, and α-actinin (iii); and between linker proteins and integrins (iv). Clustering of integrin complexes (ii) may also be involved.

Recently, several cytoplasmic proteins have been identified that are tyrosine phosphorylated during cell adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins but not when the cells are attached to uncoated plastic or to poly-l-lysine-coated surfaces (25, 213). The proteins include p125FAK, a tyrosine kinase localized to focal adhesions (325), paxillin (373, 371), tensin, and actin binding protein (25). Inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity led to diminished phosphorylation and inhibited the formation of focal adhesions and stress fibers (36). Phosphorylation of linker proteins on the cytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane is intimately involved in cell adhesion and focal adhesion dynamics in fibroblasts. We have recently examined the phosphorylation state of endothelial cells. Antiphosphotyrosine Western blots of lysates of adherent endothelial cell monolayers demonstrated two prominent groups of proteins at 116–125 kDa and 65–75 kDa that were identified on immunoblots as p125FAK and paxillin, respectively. Both were shown to be associated with endothelial focal adhesion sites by immunofluorescence. Within 2 h of exposure to unidirectional laminar flow at 12-dyn/cm2 shear stress, paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation increased greater than twofold when compared with no-flow monolayers (A. Banega, H. Tipping, and P. F. Davies, unpublished data). In contrast, p125FAK phosphorylation remained near control levels. Paxillin phosphorylation may be involved in the intracellular mechanotransduction of blood flow forces in endothelial cells. Romer et al. (309) have demonstrated increased tyrosine phosphorylation of p125FAK in HUVECs during migration into a wound in the monolayer in the absence of flow; however, no changes in paxillin were identified, although Burridge et al. (36) have shown a role for tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin as well as p125FAK in cytoskeletal assembly. The cytoskeletal reorganization during endothelial exposure to flow would be consistent with changes of paxillin activity. Absence of changes in p125FAK phosphorylation is consistent with a constant level of cell adhesion as measured by digital image analysis (70). Signaling mechanisms that involve different members of the integrin family are poorly understood but appear to involve specific phosphorylation events. p125FAK and proteins that contain homologous domains of src binding domains (SH-2 and SH-3) appear to be primarily involved (87, 325, 402).

Recent work suggests convergence of signaling pathways at the integrin-rich focal adhesion sites. Hansen et al. (128) reported the localization of a heterotrimeric G protein γ-subunit (γ5) to these regions and to adjacent stress fibers in a variety of cells. The distribution of γ5 was most similar to that of zyxin, a protein that binds α-actinin (56) and is considered to be involved in focal adhesion signal transduction (87). When the G protein-coupled receptors for endothelin and bombesin were stimulated by agonist binding, there was immediate phosphorylation of p125FAK (402), suggesting the localization of these receptors to focal adhesion sites. The colocalization of the γ5-subunit of G proteins is consistent with convergence of signaling pathways involving two families of transmembrane proteins: G protein-linked receptors and integrins. Heterotrimeric G proteins may therefore also be involved in integrin receptor signaling. Arcangeli et al. (11) have shown that pertussis toxin inhibition of G protein activation interfered with a cell adhesion-activated potassium channel that is linked to integrin-extra-cellular matrix binding.

Considering the dynamic state of focal adhesion sites and their involvement in mechanical responses of endothelial cells to shear stress (63, 64, 70), it seems reasonable that both phosphorylation and G protein-linked pathways may be involved in mechanical signaling at these sites, as well as at the luminal plasma membrane.

E. G Protein-Linked Receptors

In a review of sensory transduction, Shepherd (342) drew attention to common aspects between vision, hearing, photoreception, olfactory transduction, and mechanoreception at the molecular level. The conversion of stimulus energy to a sensory response that eventually involves ion channels resides primarily in two types of mechanisms: 1) direct displacement, as for example in hearing (149) or mechanical poking (115), and 2) the interactions of molecules (or photons) with transmembrane receptors, as occurs for vision, olfaction, and taste (342). This distinction is essentially the same as that discussed for alternative (displacement vs. agonist-mediated) mechanisms of shear stress responses alluded to earlier in this review and discussed more fully in sections VII and VIII. In sensory transduction systems, seven transmembrane domain G protein-linked receptors (serpentine receptors) are commonly involved (342). Considering that G proteins play a prominent role in the regulation of the cardiovascular system (174, 303), what is the evidence that the serpentine superfamily of transmembrane receptors may participate in mechanotransduction of hemodynamic forces in the endothelial cell?