Abstract

Epithelia are planar tissues that undergo major morphogenetic movements during development. These movements must work in the context of the mechanical properties of epithelia. Surprisingly little is known about these mechanical properties at the time and length scales of morphogenetic processes. We show that at a time scale of hours, Xenopus gastrula ectodermal epithelium mimics an elastic solid when stretched isometrically; strikingly, its area increases twofold in the embryo by such pseudoelastic expansion. At the same time, the basal side of the epithelium behaves like a liquid and exhibits tissue surface tension that minimizes its exposed area. We measure epithelial stiffness (~1 mN/m), surface tension (~0.6 mJ/m2), and epithelium–mesenchyme interfacial tensions and relate these to the folding of isolated epithelia and to the extent of epithelial spreading on various tissues. We propose that pseudoelasticity and tissue surface tension are main determinants of epithelial behavior at the scale of morphogenetic processes.

Epithelia are a fundamental tissue type. They drive morphogenesis during embryonic development and in regenerative processes such as wound healing. Epithelial cells possess distinct apical and basolateral membrane domains and are linked by lateral contacts to form 2D sheets with apical and basal surfaces. The sheets can actively bend, change in thickness, or deform by in-plane cell rearrangement (1, 2). Whereas these morphogenetic movements are mostly driven by specific cell behaviors, epithelia also have general mechanical properties that determine the context in which the specific cellular processes must work (e.g., ref. 3).

Viscoelastic mechanical properties of epithelia have been examined at short length and time scales, i.e., in response to small deformations that last up to seconds (e.g., refs. 4–8). However, morphogenetic processes typically encompass hundreds to thousands of cells, involve large deformations, and take minutes to hours, yet only a few attempts have been made to analyze the large-scale mechanical properties of epithelia (e.g., refs. 9 and 10). We use the ectodermal epithelial layer of the Xenopus gastrula to characterize such properties. We observe and analyze the long-term behavior of isolated epithelial patches, which fold in on themselves, and of epithelial patches placed on mesenchymal tissue substrates, on which they either spread or retract. We show from such experiments that at a time scale of hours, the Xenopus epithelium exhibits pseudoelasticity; i.e., it mimics elasticity, giving the epithelium a solid-like character. This result is unexpected, because most tissues show elasticity at short time scales, whereas in the long term, viscous flow dominates (11). Moreover, we show that in parallel to its solid property, the epithelium does exhibit aspects of liquid-like behavior, in the form of tissue surface tension on its basal surface. The concept of surface tension has previously been used to describe the liquid-like properties of mesenchymal aggregates (12–16). We demonstrate that it can similarly be applied to explain epithelial behavior. Altogether, we argue that the interplay of pseudoelasticity and tissue surface tension is a main aspect of epithelial tissue mechanics.

Results

Ectodermal Epithelial Layer of the Early Embryo.

In the Xenopus gastrula, the single-layered ectodermal epithelium is attached to the inner ectoderm (Fig. 1 A and E). Both layers spread in the process of epiboly to cover the embryo by the end of gastrulation. Epithelial cells divide, but because tissue volume increase is negligible during gastrulation, the epithelium becomes proportionally thinner as it spreads (17, 18). An isolated epithelial patch (Fig. 1A′′) exhibits two surfaces. Apically, cells are tightly linked to form a cobblestone pattern (Fig. 1A′). Basally, the same cells are dynamically connected, with protrusions extending across gaps (Fig. 1A′′′). We expect that here, cells are free to increase their mutual contacts at the expense of exposed surface, endowing the basal side with the liquid-like behavior known from mesenchymal tissue, i.e., with tissue surface tension that minimizes its area; apically, where cells are stably linked, this process should not take place (Fig. 1K).

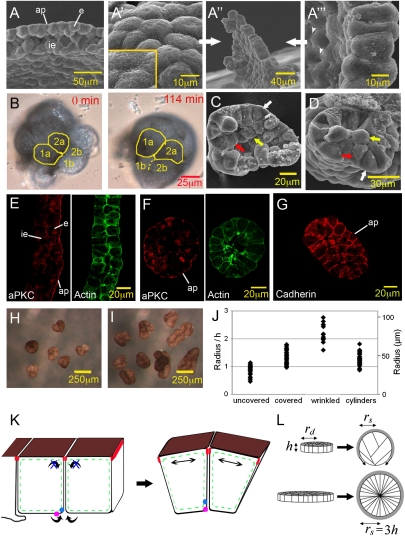

Fig. 1.

Folding of epithelial patches. (A) SEM picture of ectoderm with epithelial (e) and inner ectoderm (ie) layer; ap, apical surface. (A′–A′′′) Epithelial patch immediately after isolation. (A′) apical surface; (A′′) lateral view; (A′′′) basal surface with loosely connected cells and protrusions (arrowheads). (B) The apical surface (pigmented) of two cells (outlined in yellow; 1a, 2a) expands during rounding up. Cells were followed frame by frame. Boundaries between basal parts of same cells (1b, 2b) are barely discernible. (C) Fractured epithelial spherule, with wedge-shaped cells (white arrow), bottle cell (red arrow), and central cells (yellow arrow). (D) Fractured cylindrical wrinkle, arrows as in C. (E) Sectioned ectoderm double stained with antibody against aPKC (red) and actin (green). (F) Epithelial spherule stained as in E. (G) Spherule stained with C-cadherin antibody. (H) Explants above 66 μm radius wrinkle into connected spheres. (I) Even larger explants wrinkled into bent cylinders. (J) Explant structure and explant size. To determine critical sizes, patches were cultured for 4 h and scored for being completely or incompletely covered or wrinkled. Transition between incompletely (n = 32) and fully covered (n = 33) at a radius of 37 μm is shown. Onset of wrinkling, n = 14; radii of cylinders, n = 57. Horizontal lines are at multiples of epithelial height. (K) Cells of a folding sheet, with apical (brown) and lateral and basal (white) surfaces, subapical junctional complex (red), and actin cortex (green). Arrows and magenta/blue dots indicate movement of basal surface, and double arrows show apical expansion. (L) Patch size and spherule size. The apical side of the single-layered patch is shaded. Extreme cell elongation (at r = 3h) is avoided by wrinkling.

Folding and Wrinkling of Isolated Epithelial Patches.

We first observed the equilibrium shapes that are assumed by isolated epithelial patches. Such patches do not form flat or gently curved sheets, as intuitively expected. Instead, they spontaneously fold and wrinkle into shapes that minimize exposed basolateral surface. Sufficiently small patches fold into spherules (Fig. 1 B, C, and L). In spherules, cells are wedge shaped (Fig. 1 C, F, and G). They are outlined by an actin-rich cortex (Fig. 1 E and F), and as expected (19, 20) all basolateral, but not the apical, membranes express C-cadherin (Fig. 1G). The volume of these nongrowing cells is reduced from 10,700 ± 2,300 μm3 (n = 13) at explantation to 4,700 ± 1,700 μm3 (n = 7) 3 h later, indicating one round of division. Surprisingly, central cells that lack contact to the apical surface are present (Fig. 1C), and bottle-shaped cells (Fig. 1C) did suggest ingression of cells. However, the small apices of bottle cells are stable, and no case of ingression was observed when 6 explants were recorded over 3 h each (81 cells initially; eventually, through divisions, 148 cells). Instead, dividing cells occasionally give off daughters to the interior (Fig. S1 A–F). These divisions are asymmetrical, generating surface cells with an apical domain and interior daughter cells with basolateral membranes only (Fig. 1 E–G and Fig. S1 E, G, and H), as indicated by the apical marker aPKC (21) and basolateral markers C-cadherin (19, 20) and integrinβ1 (22). Asymmetrical divisions may be induced by radial cell elongation in spherules (see below); such divisions also occur at earlier stages in the embryo when cells are likewise more columnar (18).

Epithelial folding and wrinkling exhibit characteristic regularities. Geometrical consideration shows that to bury all exposed basolateral surface inside a spherule with radius rs and surface As, the initial apical surface area Ad must stretch by As/Ad = 3h/rs, with h being the initial height of the epithelial patch (SI Text, Section 1). However, below a certain rs, surface tension may be unable to promote full covering; it would then stretch the apical domain to incompletely cover the spherule until it is balanced by restoring forces. Apical expansion on folding epithelial patches is indeed seen in time-lapse recordings (Fig. 1B). An instance of incomplete covering of spherules by the apical domain is shown in Fig. 1B; incomplete covering is generally observed below a critical spherule radius of rs = 37 μm (Fig. 1J).

For covered spherules (rs > 37 μm), as rs increases further, the required expansion of the apical surface diminishes, until it vanishes at rs = 3h. From geometry alone, above rs = 3h one would expect the excess available apical surface to result in wrinkled (nonspherical) shapes. However, well below this size, which at an epithelial height of 37 μm (see below) would correspond to rs = 111 μm, explants become wrinkled. Starting at rs = 66 μm, they become subdivided by crevices into connected partial spheres (Fig. 1 H and J). In another experiment, the transition was seen at rs = 65 μm. With further size increase, cylindrical folds develop (Fig. 1I), with fold radii varying around an average of 45 μm (Fig. 1J). In cross-section, these folds appear similar to sectioned spheres (Fig. 1D).

The observed wrinkling of spherules at radii below rs = 3h can be understood by considering the extremely elongated cell shapes that would otherwise be necessary in such explants (Fig. 1L). We propose that such cell shapes are absent due to an elastic energy. Thus, with increasing spherule size, apical elastic expansion diminishes, but cells become more and more stretched radially. At some point, total strain energy may be reduced if spherules wrinkle into smaller connected spherules of the same total volume. An approximate analysis (SI Text, Section 1; Fig. S5) suggested that wrinkling indeed becomes energetically favorable at rs ~ 69 μm, close to the observed 66 μm. A similar calculation for cylindrical wrinkles gave a minimum in strain energy at a cylinder radius of 53 μm, reasonably close to our measured average of 45 μm.

Thus, two characteristic radii are observed during epithelial folding, which mark the transitions to complete apical covering and to wrinkling; a related one characterizes the dimension of cylindrical wrinkles in larger explants. Wrinkles are stable for hours, showing no tendency to minimize apical surface area. This observation suggests that effective surface tension is restricted to the basal side, consistent with epithelial structure (Fig. 1K). Moreover, it implies that elasticity of the tissue resists its deformation at the time scale of hours. Together, these observations suggest that spontaneous epithelial folding and the resulting equilibrium shapes of isolated epithelia can be understood as arising from the combination of basal side tissue surface tension and elasticity.

Pseudoelastic Deformation of Epithelial Explants.

The unexpected implication that tissue elasticity cannot be neglected even during very prolonged deformations was confirmed by further experiments. Elasticity is indicated by the reversibility of apical expansion in epithelial spherules. When spherules cultured for 3 h are treated with the Ca2+ chelator EDTA to disrupt adhesion of basolateral membranes, folding is reversed, and apical cell surfaces shrink within minutes (Fig. 2A).

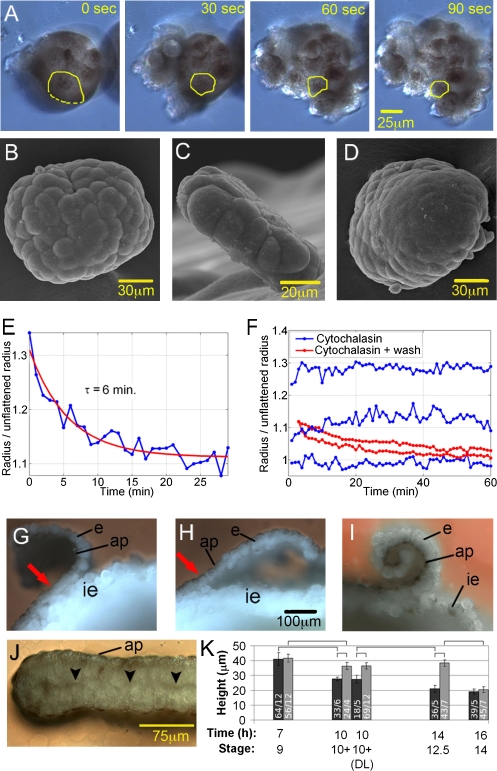

Fig. 2.

Elasticity of epithelium. (A) Spherical epithelial explant treated with EDTA after 3 h. Apical (pigmented) cell surface (yellow outline) shrinks. (B–E) Flattening of spherules by compression. Spherules (3 h after explantation) before (B) and 30 min after compression (D) are shown. (C) Flattened explant 120 min after start of compression. (E) Recoil after compression; τ, time constant. (F) Recoil for flattened explants treated with cytochalasin D and explants treated with cytochalasin D followed by washing with MBS for 1 h. (G–I) Recoil of epithelial patch in situ. Fixed and fractured embryos, ectodermal region, are shown. The epithelium (e) was cut at three sides and peeled off the inner ectoderm (ie). The patch, attached at the fourth side (arrow), curls back, shortening its apical side (ap) (G), and then straightens within <1 min (H). No straightening occurs in EDTA buffer even after 5 min (I). Patches were oriented randomly; no indication of in-plane anisotropy was noted. (J) Two stage 10+ epithelial patches attached with their basal sides (arrowheads) form a double layer: fixed and fractured 1 h after explantation. (K) Height of epithelium at different stages in intact embryo (dark gray bars) and after straightening of patch, as in H, or in double layer (DL), as in J (light gray bars). Error bars, SDs; significant differences at same stage and between stages are marked with brackets. Numbers inside bars indicate numbers of measurements and embryos.

In other experiments, we compressed spherules (Table 1 and Fig. 2B) under a coverslip to induce a 1.5- to 2.1-fold increase in surface area (Fig. 2C). When released after 3–4 h, explants immediately rounded up (Fig. 2D), again suggesting elastic behavior. The time constant for the recoil (Fig. 2E) was of order 5 min (Table 1), similar to time constants for contraction of gastrula epithelium subjected to nonspecific stimuli (23). If true elastic deformation were involved, a spring-like stretching of some structural component of the cell would have to be maintained over hours and through cell divisions. To probe this, we attempted to temporarily disrupt tension by treating explants with cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of the actin cytoskeleton. After being compressed for 1 h in the presence of inhibitor, explants retracted briefly during lifting of the coverslip, as they tended to stick to it, but then remained flattened (Fig. 2F and Fig. S3). However, when the inhibitor was washed out after 1 h and explants were kept compressed for an additional 2 h, they recoiled like untreated explants when finally released (Fig.2F and Fig. S3). Thus, “elastic” stress need not be maintained uninterruptedly, but can be restored after inhibition. Apparently, explants imitate solid behavior, showing pseudoelasticity (24).

Table 1.

Flattening and rerounding of epithelial spheres

| Patch | Initial radius, μm | Flattened surface area/A0 | Final surface area/A0 | Time constant, min |

| a | 78 | 1.64 | 1.06 | 6 |

| b | 79 | 1.68 | 1.24 | 6 |

| c | 111 | 2.13 | 1.03 | 12 |

| d | 112 | 1.96 | 1.09 | 3 |

| e | 74 | 1.47 | 0.90 | 5 |

| f | 85 | 1.55 | 0.75 | 2 |

| Average ± SD | 1.01 ± 0.17 | 5.7 ± 3.5 |

A0, initial surface area; time constant measured for rerounding. The final surface area of an explant divided by the initial one gives values close to unity.

Pseudoelastic Deformation in Epiboly.

To see whether pseudoelastic deformation also plays a role in vivo, we observed the ectodermal epithelium during epiboly, when its area increases twofold and its thickness decreases correspondingly (18, 25). We confirmed that epithelial height decreases by half between the late blastula and the end of gastrulation (Fig. 2K). When the epithelium is locally detached, it immediately curls outward (Fig. 2G). Within <1 min, bending is reverted (Fig. 2H), but not when basolateral cell adhesion is prevented by EDTA treatment (Fig. 2I). Apparently, tensile elastic stress is concentrated apically, but is counteracted by basal surface tension (Fig. 1K), which eventually would fold up the patch. When epithelium is detached at different stages of gastrulation and fixed when straightened (Fig. 2H), i.e., when cells are not wedge shaped but columnar as in the embryo, epithelial height is always the same regardless of how much it was decreased by epiboly at the time of detachment (Fig. 2K), indicating retraction of the epithelium. The average height of the straight epithelium, 37 μm, corresponds to that of late blastula embryos. At that stage, the epithelium does not increase in height upon detachment (Fig. 2K). This result suggests that the 1.8-fold expansion in epithelial area (corresponding to a decrease in height from 37 to 20 μm) over 7 h between late blastula and late gastrula stages (18, 25) is due to pseudoelastic stretching; if tension is released, the epithelium retracts and always returns to the same preset target height. After gastrulation, retraction is minimal again (Fig. 2K). Apparently, the epithelium has now adopted a new target height.

These observations were made as the detached epithelium passed through a straight configuration while being gradually folded up by its basal side surface tension. In the embryo, folding is prevented as the epithelium is attached to the underlying inner ectoderm. In explants, epithelia can be kept straight by creating a double layer, i.e., by joining two epithelial patches on their basal sides (Fig. 2J). After 1 h under this condition, epithelial thickness is seen to have increased to the same target height (~37 μm) as after local detachment and straightening (Fig. 2K). As thickening after explantation already occurs within 1 min, epithelial shape must be stable in these double layers. The result also implies, again, that the effective apical side surface tension is close to zero. Indeed, when an epithelial patch is kept in Ca2+/Mg2+-free medium to prevent rounding up, the apical surfaces of cells do not shrink (Fig. S4), confirming that the apical surface tension is negligible. To summarize our results thus far, the epithelium reacts pseudoelastically when stretched in vitro and in vivo and exhibits tissue surface tension on the basal, but not the apical side.

Epithelial Spreading: Analysis.

Epithelial layers are often attached on their basal side to another tissue, as in the case of the gastrula ectoderm studied here, or in stratified epithelia. To quantitatively understand the spreading of an epithelium on a mesenchymal tissue, we apply the concept of tissue surface tension to the pseudoelastic epithelium.

The adhesive interaction of two mesenchymal aggregates can be modeled as that between two liquid drops (26). Epithelia exhibit liquid-like surface minimization on only the basal side, requiring an adjustment to the theory (SI Text, Section 2). We find that, for an epithelium placed on any mesenchyme (Fig. 3A), spreading should ensue if γem < γm, where γm is the surface tension of the mesenchyme and γem the interfacial tension between epithelium and mesenchyme. The extent of spreading (Fig. 3B) depends on the stiffness of the epithelium: In equilibrium, surface tension is balanced by elasticity. The change in epithelial thickness, as a measure of spreading, is (27)

|

where k is an epithelial stiffness, h is its initial height (thickness), and Δh is the change in height (negative for spreading) (SI Text, Section 2).

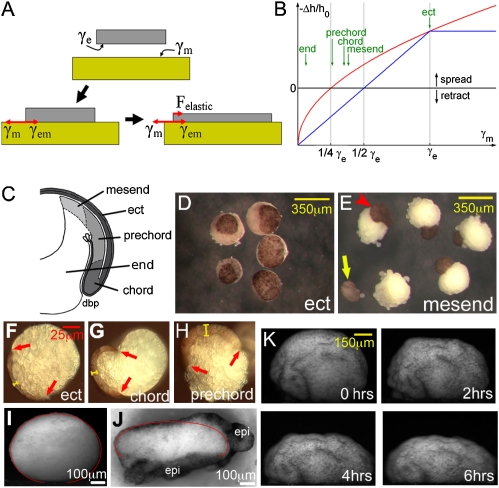

Fig. 3.

Spreading of epithelial patches. (A) Surface tensions and elastic force during spreading. Gray, epithelium; yellow, mesenchyme. γe, epithelial; γm, mesenchymal surface tension; γem, interfacial tension. (B) Mesenchymal surface tension and epithelial spreading (Eq. 1), with interfacial tension estimated according to Eq. 2 (blue) or Eq. 3 (red). (C) Regions of embryo: mesend, leading edge mesendoderm; ect, ectoderm; prechord, prechordal mesoderm; end, endoderm; chord, chordamesoderm; dbp, dorsal blastopore. (D and E) Patches spread on inner ectoderm (D) or retract (E) (arrowhead) or detach (arrow) on mesendoderm. (F–H) Epithelial patches (between red arrows; yellow bar, thickness) on mesenchymal explants, fixed after 3 h, and transected. (I–K) Surface tension of coated explants. Transected inner ectoderm explant after 5 h of flattening is shown without (I) or with (J) excess epithelial (dark; epi) coating. Red, Laplacian contour fit to explant. (K) Time course of flattening of epithelium-coated inner ectoderm, lateral view.

From the above equation, to predict spreading, knowledge of γem is required. Because interfacial tensions are notoriously difficult to measure, they are usually estimated from the easier-to-measure surface tensions of the individual tissues (SI Text, Section 2). Two commonly used assumptions are

and

where γe is the basolateral surface tension of the epithelium. The condition for spreading (γem < γm) then becomes either γe < 2γm (from Eq. 2) or γe < 4γm (from Eq. 3) (Fig. 3B). Importantly, by taking advantage of the spring-like property of epithelial patches, relationship Eq. 1 can be used to directly measure interfacial tensions γem (see below).

Epithelial Spreading: Observations.

We tested the above model by observing epithelial patches attached to mesenchymal tissues. When a patch spreads on a large explant of inner ectoderm (Fig. S5A), expansion as a function of time fits a dying exponential (Fig. S5 B and D), consistent with viscoelastic behavior. When adhesion to the inner ectoderm is released by addition of EDTA, patches rapidly shrink back to their original sizes (Fig. S5A and Table S1), also indicating an elastic restoring force.

To examine spreading on tissues of different surface tensions, we measured γm for several gastrula tissues using axisymmetric drop shape analysis (Fig. 3I, Table 2, Fig. S6, and SI Text, Section 3). This method determines surface tension by analyzing the flattened equilibrium shape of a cell aggregate under normal gravity. To estimate γe, we first measured the interfacial tension γem in epithelium-coated inner ectoderm aggregates using the same method (Fig. 3 J and K and SI Text, Section 3). In short, aggregates flattened until an equilibrium was reached (Fig. 3K). Assuming that further flattening was prevented by interfacial tension (enough epithelium was used that it coated the aggregates without stretching), Laplacian profiles were fitted to the boundaries between inner cells and epithelium (39) (Fig. 3J). The measured average γem was 0.016 ± 0.005 mJ/m2 (n = 8), very small compared with the average γm = 0.57 ± 0.26 mJ/m2 for uncoated inner ectoderm (Table 2). Thus, from either Eq. 2 or Eq. 3, γe ~ γm = 0.57 mJ/m2.

Table 2.

Spreading of epithelium on mesenchymal substrates

| γm | γm/γe | γem2 | γem3 | Observation, % spread | γemmeas | |

| Ectoderm | 0.57 ± 0.26 | 1 | 0 (S) | 0 (S) | 100 | — |

| Chordamesoderm | 0.20 ± 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.37 (R) | 0.09 (S) | 90 | −0.11 |

| Prechordal mesoderm | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.42 (R) | 0.14 (S) | 81 | 0.10 |

| Leading edge mesendoderm | 0.22 ± 0.12 | 0.39 | 0.35 (R) | 0.08 (S) | 0 | — |

| Endoderm | 0.044 ± 0.022 | 0.08 | 0.53 (R) | 0.31 (R) | 0 | — |

Δh, the change in epithelial height, was measured for inner ectoderm (–17.8 ± 4.0 μm, n = 9), chordamesoderm (–9.8 ± 7.7 μm, n = 10), and prechordal mesoderm (–1.7 ± 2.4 μm, n = 7). Averages and SDs (n = 8–11) of surface tensions are shown, in mJ/m2. Differences between mesoderm regions are not significant. γem2 is according to Eq. 2; γem3 is according to Eq. 3; γemmeas, measured value; S, prediction of spreading; R, prediction of retraction. Detailed observations on spreading are in Table S2.

From the knowledge of γe and the various other γms (Table 2), we estimated other γems conventionally according to Eqs. 2 and 3 and used them to predict spreading from the condition γem < γm. In experiments, spreading occurred on inner ectoderm, chordamesoderm, and prechordal mesoderm, but not on leading-edge mesendoderm or endoderm (Fig. 3 C–E, Table 2, and Table S2). Thus, both rules correctly predicted spreading for the extremes of surface tensions γm, but gave different results closer to the critical value for spreading (Table 2).

We also used Eq. 1 to directly measure interfacial tensions for those combinations where spreading occurred. Explanted epithelia were placed on aggregates, and cross-sections analyzed when spreading became maximal (Fig. 3 F–H). At this point, γem = γm + k·Δh/h with h = 37.0 μm. Measurements of Δh, the change in height, were made for substrates of inner ectoderm, chordamesoderm, and prechordal mesoderm (Table 2). Using the known γem ~ 0 for the epithelium/inner ectoderm case, k was determined as 1.2 mN/m. This value was then used to calculate γem for the two other substrates (Table 2). Measured values were close to those predicted by Eq. 3, which altogether performed better than the alternative Eq. 2. However, it failed to predict epithelial retraction on leading-edge mesendoderm (Table 2). Likewise, for chordamesoderm, a negative value of γem was measured. These anomalies could indicate molecular induction of increased or decreased adhesion in one or both interacting tissues, i.e., biological effects that are not captured by relations of the form of Eqs. 2 and 3. This result stresses the importance of direct measurements of tissue interfacial tensions. In fact, even with pure liquids, interfacial tensions are not in general predictable from individual surface tensions (28).

Discussion

A striking finding of our study is the long-term pseudoelastic behavior of the Xenopus ectodermal epithelium. It is usually assumed that tissue elasticity observed during short deformations eventually gives way to liquid-like behavior under long-lasting strain (20). For epithelia, a transition from elastic deformation to viscous flow at subsecond time scales has been demonstrated at the cell level (4–8), but paradoxically, mechanical strain maintained for hours is not sufficient to cause permanent changes in epithelial shape. Long-term elastic deformation has also been observed in axolotl neurula ectoderm (10).

A clue to resolve this discrepancy lies in our finding that Xenopus gastrula epithelium returns to its target shape even after transient relaxation due to a disruption of the cytoskeleton (Fig. 2F). This result is not compatible with a truly elastic recoil of structural components that act as springs, but with a mechanism that dynamically maintains a preset morphological shape by a cell biological process, thus mimicking elastic behavior (24). Chen and Brodland (29) and Derganc et al. (30) proposed models where an equilibrium epithelial height results from the combined effects of tensions on the apical, basal, and lateral surfaces of cells. These models predict long-term elastic behavior, but they assume constant cell proportions. Cell divisions without cell growth, as in the ectodermal epithelium, would reduce epithelial height in these models, but height is conserved in our experiments.

In fact, due to these cell divisions, the apical area of a cell and its height/width ratio are not constant if height is conserved. This condition would favor mechanisms based, for example, on maintaining the density of stable factors in apical and basolateral membranes: If “diluted” by stretching, contraction would be induced until the target density of such a factor is restored. Identifying the actual molecular mechanism will be an interesting topic for future study. We predict that the molecular process that restores target cell shape after deformation will be slow enough to reconcile viscous behavior at very short time scales (4–8) with seemingly elastic behavior at times characteristic for tissue-level morphogenetic processes (e.g., ref. 3 and this article).

We identified pseudoelastic behavior in the context of passive epithelial deformations. An important question is whether molecular processes that drive active epithelial shape changes, such as apical constriction (2), are superimposed on an independently controlled pseudoelastic resistance. In gastrula epithelium, target shape is eventually reset at the completion of epiboly, thus relaxing mechanical stress (Fig. 2K). It is conceivable that in other systems, this resetting occurs more or less continuously, leading to a plastic deformation that avoids building up mechanical stress when epithelium is deformed by outside or endogenous forces. On the other hand, resetting the target shape in a nondeformed epithelium could itself be used to generate mechanical stress, driving, for example, the transition from a flat to a columnar epithelium.

In Xenopus, epiboly has been well described at the cellular level, but its driving forces are still unknown. The movement comprises an interdigitation of inner ectoderm cells in the radial direction, which expands this layer laterally, and a concomitant thinning and spreading of the epithelial layer (15). Our results show that the shape change of the epithelium is due to its passive pseudoelastic stretching. Radial intercalation of the inner ectoderm is probably not an active process either (31), suggesting that tissue movements in the lower part of the gastrula (Fig. 3C) indirectly drive epiboly. To achieve this, forces generated by active cell rearrangement in this region, e.g., during involution, convergent extension, or vegetal rotation (31), would need to be sufficient to produce the observed twofold stretching of the epithelium during epiboly. We found that, coincidentally, the epithelium is also stretched twofold when spreading on a substrate of inner ectoderm (Table 2). In this case, the driving force is the surface tension of the inner ectoderm. Because forces generated by active cell rearrangement in the mesoderm have similar magnitude to those due to tissue surface tension (32), such cell rearrangements should indeed be able to drive epiboly.

A second main finding of our study is the relevance of surface tension in epithelial mechanics. We showed that this concept can be used to quantitatively characterize the liquid-like behavior of the basal surface of epithelia, where cells can attempt to move over each other, or “zipper up,” to minimize exposed surface area. As a consequence of surface tension being restricted to the basal side (Fig. 1K), folding and wrinkling occur in isolated epithelia. Normally, this is prevented in vivo by straining the epithelium or by diminishing basal surface tension through attachment to a basal lamina (33) or to mesenchymal tissue; but folding and wrinkling occur in mutations affecting epithelial integrity in the Drosophila embryo (34). Whether basal side surface tension is also constructively used to support morphogenetic processes remains to be seen.

When attached to mesenchyme, basal side surface tension of the epithelium is replaced by an interfacial tension. It is in principle independent of the elastic tension in the epithelium, which has interesting implications. For example, external forces could stretch an epithelium sitting on mesenchyme beyond the limit that spreading would attain. If wounded, the epithelium would show large-scale retraction, and wound closure would require mechanisms such as a contractile supracellular actomyosin ring in the epithelial margin (3). By contrast, if elastic stress is below this limit, the epithelium would remain attached behind the wound margin, as in gastrula ectoderm, and healing could occur by respreading.

From our data, we calculated basic properties of the gastrula epithelium. We estimated an epithelial stiffness k = 1.2 mN/m, which would correspond to an elastic modulus E = k/h = 32 Pa. For axolotl embryonic epithelium, 20 Pa was reported (10), but for blastula epithelium of sea urchins much higher values were found, of <700 Pa (4) and 450 Pa (35). When multiplied by epithelial height (37, 80, and 10 μm, for Xenopus, axolotl, and sea urchin, respectively), stiffness values of 1.2, 1.6, 7.0, and 4.5 mN/m are obtained, which are more consistent, implying that epithelial elasticity is best modeled by a stiffness (N/m) rather than an elastic modulus (N/m2); i.e., it is concentrated in two dimensions. A reason for this might be that apical cytoskeleton–cell junction complexes could bear most of the stress due to stretching. From τ, the time constant for the recoil of spherules (Table 1), a viscosity can be estimated as η = τk/h = 11 kPa·s, higher than typical cytoplasmic or single-cell viscosities (e.g., refs. 36 and 37), but similar to that of sea urchin embryo epithelium (4). Altogether, from the comparison of the few examples known, it appears that embryonic epithelia from different sources are similar in their long-term, large-scale mechanical properties. Basal side tissue surface tension has not been determined for the other epithelia. We found that it is similar to that of mesenchymal tissues, at 0.57 mJ/m2.

In summary, current models (e.g., refs. 24 and 25) assume surface/cortical tensions on all sides of single cells, which usually differ apically, basally, and laterally and balance each other in equilibrium to provide a flat or gently curved epithelial sheet. In contrast, we observed that sufficiently large epithelial patches round up until all basal surface is buried within the explant; but when this basal surface minimization is neutralized, the apical surface adopts a preset target size and does not continue to shrink beyond it. Thus, we ascribe to the basal side of the epithelium a tissue-level surface tension, which at the cell level includes contributions from adhesion and cortical contractility (21); stretching will peel off cells from each other. To the apical side we attribute an elastic stiffness and a negligible tissue-level surface tension; here, stretching will lead to the pseudoelastic expansion of the surface (Fig. 1K). The simultaneous presence of solid- and liquid-like behavior in the same single-layered tissue is an essential property and can be rationalized from the polarized epithelial structure. Whereas in a cell level description, a large number of parameters have to be accounted for, such as adhesiveness at basal and lateral membranes or cortex contractility, empirical observation suggests that at the tissue level, on the basis of differences between apical and basal cell interactions, a stiffness k and a surface tension γ are sufficient to describe large-scale and long-term static behavior. These tissue-level parameters allow for a simplified description of morphogenetic processes and help to guide the analysis of their mechanical design.

Materials and Methods

Embryos and Microsurgical Operations.

Operation techniques and modified Barth's solution (MBS) have been described (38). Epithelial patches were peeled off the animal region of the ectoderm at stage 10+ and allowed to round up or placed on mesenchyme explanted 10–20 min earlier. Explants were observed in MBS or fixed in 4% formaldehyde in MBS and observed whole or after bisecting with a blade.

Scanning Electron Microscopy.

Embryos/explants were fixed in 2.5% formaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in MBS, postfixed in 2% OsO4, dehydrated in ethanol and hexamethyldisilazane, dried, mounted on stubs, and sputter coated with gold-palladium.

Time-Lapse Recordings.

Time-lapse movies were made at 1 frame/min (Zeiss AxioVision software). For lateral views, explants were viewed in a mirror inclined at 45°.

Immunohistology.

Explants were fixed; sectioned; stained with antibodies against actin (Cedarlane; CLT9001), aPKC (Santa Cruz Biotech; SC-216), α-tubulin (Sigma; T9026), C-cadherin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; 6B6), and integrinβ1 (ref. 22; 8C8); and visualized by fluorescence or confocal microscopy as described (32).

Measurement of Surface Tension.

Axisymmetric drop shape analysis (ADSA) was used as described (39), except that we did not centrifuge explants as we had noted that centrifugation caused an artificial increase in apparent surface tension. Details are in SI Text, Section 3.

Measurement of Explant Dimensions.

Explant images were processed by an edge detector (Canny) in Matlab, and equivalent radii were calculated and least-squares fitted to dying exponentials in time. Details are in SI Text, Section 3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tony Harris, Craig Simmons, Ashley Bruce, Ulli Tepass, Edgar Acosta, and Wilhelm Neumann for critical comments. This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant MOP-53075 (to R.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. K.Y. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1010331108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schock F, Perrimon N. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial morphogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:463–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.022602.131838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilot F, Lecuit T. Compartmentalized morphogenesis in epithelia: From cell to tissue shape. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:685–694. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin AC, Gelbart M, Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Kaschube M, Wieschaus EF. Integration of contractile forces during tissue invagination. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:735–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson LA, Oster GF, Keller RE, Koehl MAR. Measurements of mechanical properties of the blastula wall reveal which hypothesized mechanisms of primary invagination are physically plausible in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Dev Biol. 1999;209:221–238. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcaraz J, et al. Microrheology of human lung epithelial cells measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J. 2003;84:2071–2079. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagh AA, et al. Localized elasticity measured in epithelial cells migrating at a wound edge using atomic force microscopy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L54–L60. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00475.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma X, Lynch HE, Scully PC, Hutson MS. Probing embryonic tissue mechanics with laser hole drilling. Phys Biol. 2009;6:036004. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/6/3/036004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutson MS, et al. Combining laser microsurgery and finite element modeling to assess cell-level epithelial mechanics. Biophys J. 2009;97:3075–3085. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beloussov LV, Louchinskaia NN, Stein AA. Tension-dependent collective cell movements in the early gastrula ectoderm of Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev Genes Evol. 2000;210:92–104. doi: 10.1007/s004270050015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiebe C, Brodland GW. Tensile properties of embryonic epithelia measured using a novel instrument. J Biomech. 2005;38:2087–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forgacs G, Newman SA. Biological Physics of the Developing Embryo. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinberg MS. In: Specificity of Embryological Interactions (Receptors and Recognition, Series B) Garrod DR, editor. Vol. 4. London: Chapman & Hall; 1978. pp. 99–129. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graner F. Can surface adhesion drive cell-rearrangement? Part I: Biological cell-sorting. J Theor Biol. 1993;164:445–476. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foty RA, Forgacs G, Pfleger CM, Steinberg MS. Liquid properties of embryonic tissues: Measurement of interfacial tensions. Phys Rev Lett. 1994;72:2298–2301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beysens DA, Forgacs G, Glazier JA. Cell sorting is analogous to phase ordering in fluids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9467–9471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakab K, et al. Relating cell and tissue mechanics: Implications and applications. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2438–2449. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuft P. The uptake and distribution of water in the developing amphibian embryo. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1965;19:385–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller RE. The cellular basis of epiboly: An SEM study of deep-cell rearrangement during gastrulation in Xenopus laevis. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1980;60:201–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levi G, et al. EP-cadherin in muscles and epithelia of Xenopus laevis embryos. Development. 1991;113:1335–1344. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagotto F, Gumbiner BM. β-catenin localization during Xenopus embryogenesis: Accumulation at tissue and somite boundaries. Development. 1994;120:3667–3679. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalmers AD, Strauss B, Papalopulu N. Oriented cell divisions asymmetrically segregate aPKC and generate cell fate diversity in the early Xenopus embryo. Development. 2003;130:2657–2668. doi: 10.1242/dev.00490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gawantka V, Ellinger-Ziegelbauer H, Hausen P. β 1-integrin is a maternal protein that is inserted into all newly formed plasma membranes during early Xenopus embryogenesis. Development. 1992;115:595–605. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.2.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshi SD, von Dassow M, Davidson LA. Experimental control of excitable embryonic tissues: Three stimuli induce rapid epithelial contraction. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beloussov LV, Saveliev SV, Naumidi II, Novoselov VV. Mechanical stresses in embryonic tissues: Patterns, morphogenetic role, and involvement in regulatory feedback. Int Rev Cytol. 1994;150:1–34. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller RE. Time-lapse cinemicrographic analysis of superficial cell behavior during and prior to gastrulation in Xenopus laevis. J Morphol. 1978;157:223–248. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051570209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinberg MS. On the mechanism of tissue reconstruction by dissociated cells, III. Free energy relations and the reorganization of fused, heteronomic tissue fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1962;48:1769–1776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.10.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crandall SH, Dahl NC, Lardner TJ. An Introduction to the Mechanics of Solids. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwok DY, Hui W, Lin R, Neumann AW. Liquid-fluid interfacial tensions measured by Axisymmetric Drop Shape Analysis: Comparison between the pattern of interfacial tensions of liquid-liquid and solid-liquid systems. Langmuir. 1995;11:2669–2673. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X, Brodland GW. Mechanical determinants of epithelium thickness in early-stage embryos. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2009;2:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derganc J, Svetina S, Zeks B. Equilibrium mechanics of monolayered epithelium. J Theor Biol. 2009;260:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller R, Davidson LA, Shook DR. How we are shaped: The biomechanics of gastrulation. Differentiation. 2003;71:171–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.710301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ninomiya H, Winklbauer R. Epithelial coating controls mesenchymal shape change through tissue-positioning effects and reduction of surface-minimizing tension. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:61–69. doi: 10.1038/ncb1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nardi JB, Reynolds I. Bidirectional folding of an insect epithelial monolayer. J Exp Zool. 1986;237:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tepass U, Knust E. Crumbs and stardust act in a genetic pathway that controls the organization of epithelia in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1993;159:311–326. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gustafson T, Wolpert L. The cellular basis of morphogenesis and sea urchin development. Int Rev Cytol. 1963;15:139–214. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zahalak GI, Wagenseil JE, Wakatsuki T, Elson EL. A cell-based constitutive relation for bio-artificial tissues. Biophys J. 2000;79:2369–2381. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76482-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wirtz D. Particle-tracking microrheology of living cells: Principles and applications. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:301–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winklbauer R. Mesodermal cell migration during Xenopus gastrulation. Dev Biol. 1990;142:155–168. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90159-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.David R, Ninomiya H, Winklbauer R, Neumann AW. Tissue surface tension measurement by rigorous axisymmetric drop shape analysis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2009;72:236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.