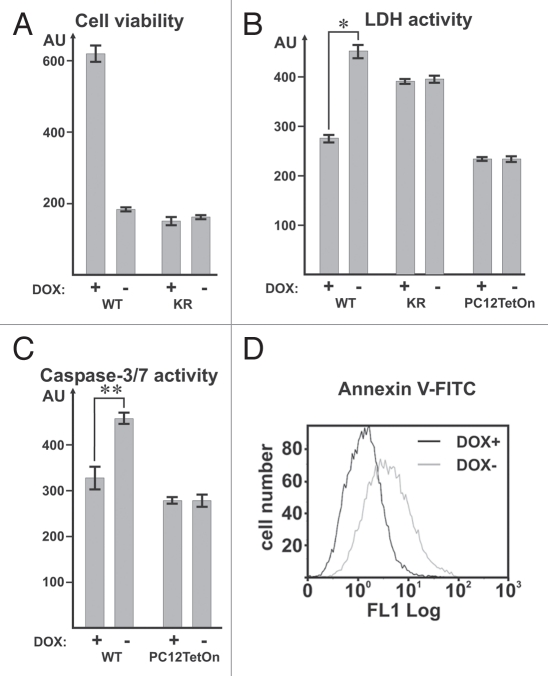

MAK-V/HUNK is an AMPK-like protein kinase which role remains largely enigmatic. MAK-V is preferentially expressed in specific cell populations in brain, kidney, mammary gland and in embryonic development.1–4 Besides that, mak-v cDNA has been isolated in a result of comparative studies of mouse tumor kinomes2,5 with later study demonstrated its frequent overexpression in human breast tumors.6 Together the data obtained strongly suggest that MAK-V might play some role in developmental processes and in nervous system and potentially its expression might determine some specific properties of tumor cells. However these suggestions are largely based on the mak-v expression pattern and just a few experimental evidences supporting them became currently available.3,7 In an attempt to reveal effects of MAK-V on cell behavior, we have used PC12 cells with doxycycline (DOX)-inducible expression of the C-terminally FLAG-tagged MAK-V protein (referred as WT cells). To ultimately address a question of specificity for the effects observed upon MAK-V expression, we generated PC12 cells with inducible expression of the kinase-dead MAK-V mutant with catalytic lysine substituted for arginine thus rendering enzyme inactive (KR cells, Sup. Fig. 1). Based on the expression pattern, MAK-V is expected to play a role in nervous system which has been recently confirmed by its involvement in Xenopus brain pattering and morphogenesis.7 We have used WT cells to directly assess if MAK-V expression affects differentiation along the neural pathway induced by nerve growth factor (NGF). NGF treatment resulted in appearance of larger number of WT cells with neurites when MAK-V expression has been induced but percentages of differentiated cells were the same irrespectively of MAK-V expression. Instead, total cell number at the end of NGF treatment was higher when cells were treated with DOX thus indicating their improved viability (Sup. Fig. 2). Indeed, when grown on collagen IV-treated surface, the conditions used in differentiation experiments, WT but not parental PC12TetOn cells showed reduced viability when not treated with DOX to induce MAK-V expression (Fig. 1A and Sup. Fig. 3). This was accompanied by the increase in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release into cell culture medium, higher caspase-3/7 activation and elevated Annexin V-FITC immunoreactivity (Fig. 1B–D). This indicates that collagen IV induces apoptotic cell death in WT cells and MAK-V expression allows cells to escape from it. Similar to WT cells, KR cells showed suppressed viability when plated on collagen IV (Sup. Fig. 3). However induction of catalytically inactive MAK-V mutant expression failed to improve their viability that was concomitant with no change in LDH release (Fig. 1A and B). Therefore improved viability of WT cells upon contact with collagen IV can be entirely attributed to the expression of catalytically active MAK-V protein kinase. WT and KR cells showed decreased viability upon contacting with collagen IV but this effect was not so pronounced when cells were grown on laminin-coated surface (Sup. Fig. 4A). At the same time, only when plated on collagen IV but not on laminin WT cells acquired spreaded morphology (Sup. Fig. 4B) indicating that formation of contacts with collagen IV but not with laminin induces rearrangements in actin cytoskeleton. Thus it is feasible that collagen IV-induced actin rearrangement can result in activation of apoptotic machinery by some unknown mechanism which is alleviated by MAK-V protein kinase activity. Interestingly, recent study linked MAK-V with actin cytoskeleton rearrangement through regulation of cofilin phoshorylation.8 However induction of MAK-V expression in WT cells had no effect on cofilin phosphorylation (Sup. Fig. 4C). This observation further supports the emerging suggestion that MAK-V activity depends on the specific cellular context and might significantly differ in different types of cells8–11 and rules out a possibility that MAK-V in WT PC12 clonal derivative directly affects actin cytoskeleton rearrangement induced by collagen IV through cofilin-1. Integrin signaling activates numerous signal transduction events including those affecting cell viability and survival, among them ERK and Akt pathways. Moreover, MAK-V was identified as one of the candidate protein kinases that might modulate EGF signaling.12 However MAK-V expression in WT cells did not alter activation of ERK signaling. Similarly, no change in Akt signaling pathway activation was evident in MAK-V expressing WT cells (Sup. Fig. 5). Therefore MAK-V protein kinase affects distinct from the assayed molecular pathway in WT cells to inhibit their apoptotic death induced by collagen IV binding. Summarizing, we showed that MAK-V expression can improve cell viability as exemplified by WT cells grown on collagen IV. This is the first study to demonstrate pro-survival activity of the MAK-V protein kinase molecular mechanisms underlying which are yet to be identified. Our findings ultimately prove previously suggested role of MAK-V in cell viability regulation derived from the results of two high-throughput RNAi screens.10,11 Importantly, MAK-V expression in tumor cells might benefit their survival in otherwise restrictive conditions, and this conclusion is supported by the reported predominant MAK-V expression in aggressive subsets of tumors.9 Although functional consequences of MAK-V expression might vary depending on the cellular context,8–11 the revealed pro-survival and anti-apoptotic activity of MAK-V signifies its role in tumor cells and prompt future research aiming to validate MAK-V as a novel target to treat cancer. In addition, MAK-V is characterized by highly patterned expression in embryonic development assuming its involvement in developmental processes. Our findings suggest a novel role of MAK-V in developmental processes through regulating cell survival and directed migration in response to contacts with specific components of extracellular matrix.

Figure 1.

(A) Viability of WT and KR cells on collagen IV. Cells were cultured for 8 days without (−) or with (+) DOX to induce transgene expression prior to determining their viability. Data are presented in arbitrary units (AU) of cellular dehydrogenase activities as average of measurements in three independent wells ± standard deviation (SD). (B) Release of LDH into cell culture medium. WT, KR or parental PC12TetOn cells were cultured for 60 hrs without (−) or with (+) DOX to induce transgene expression prior to quantification of LDH released into cell culture medium. Data are presented in arbitrary units (AU) of LDH activity as average of measurements in three independent wells ± SD. *p < 0.0001. (C) Activation of caspases-3/7 in WT and PC12TetOn cells on collagen IV. Cells were cultured for 2 days without (-) or with (+) DOX to induce transgene expression prior to quantification of cellular caspase-3/7 activity. Data are presented in arbitrary units (AU) of caspase-3/7 activity normalized to total cell number as average of measurements in three independent wells ± SD. **p = 0.0013. (D) Annexin V-FITC reactivity of WT cells on collagen IV. Annexin V-FITC reactivity in WT cells cultured for 2 days without (−) or with (+) DOX to induce MAK-V expression was analyzed by flow cytometry. See Supplemental materials for experimental details.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research and the Wellcome Trust Short Term Travel Grant 071269 and the INTAS Young Scientist Fellowship to I.V.K.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/13592

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Korobko IV, et al. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;264:411–418. doi: 10.1007/s004380000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner HP, et al. Genomics. 2000;63:46–59. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner HP, et al. Development. 2000;127:4493–4509. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.20.4493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakai M, et al. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:1526–1536. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korobko, et al. Dokl Akad Nauk. 1997;354:554–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korobko, et al. Arkh Patol. 2004;66:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kibardin A, et al. Development. 2006;133:2845–2854. doi: 10.1242/dev.02445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quintela-Fandino M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:2622–2627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914492107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wertheim GB, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15855–15860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906993106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grueneberg DA, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16472–16477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808019105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlabach MR, et al. Science. 2008;319:620–624. doi: 10.1126/science.1149200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komurov K, et al. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21134–21142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.