Abstract

It has been postulated that impulsive-compulsive spectrum behaviors (ICBs) in Parkinson's disease (PD) reflect overvaluation of rewards, resulting from excessive dopaminergic transmission in the ventral striatum. However, as the ventral striatum is also strongly implicated in delay discounting, an alternative explanation would be that, similar to stimulant-dependent individuals, PD patients with ICBs impulsively discount future rewards. To test these hypotheses, we investigated whether 36 medicated PD patients with and without ICBs differed from controls on measures of stimulus-reinforcement learning and delay discounting. There was a clear double dissociation between reward learning and impulsivity in PD patients with and without ICBs. Although PD patients without ICBs were impaired at learning stimulus–reward associations for high-probability stimuli, PD patients with ICBs were able to learn such associations equally as well as controls. By contrast, PD patients with ICBs showed highly elevated delay discounting, whereas PD patients without ICBs did not differ from controls on this measure. These results contradict the hypothesis that ICBs in PD result from overvaluation of rewards. Instead, our data are more consistent with a model in which excessive dopaminergic transmission induces a strong preference for immediate over future rewards, driving maladaptive behavior in PD patients with ICBs.

Keywords: reward learning, dopamine agonist, delay discounting, impulsivity, Parkinson's disease (PD), impulsive-compulsive spectrum behaviors (ICBs)

INTRODUCTION

The pathological hallmark of Parkinson's disease (PD) is a regionally specific loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) (Lees et al, 2009). The most severe loss of dopaminergic neurons in PD occurs in the ventrolateral and caudal portions of the SNpc, diminishing dopaminergic projections to the dorsal striatum (Bernheimer et al, 1973; Fearnley and Lees, 1991). Dopamine replacement therapy (DRT), which is used to treat PD, is hypothesized to have an overdosing effect in the relatively intact ventral striatum, leading to cognitive impairment in some domains (Cools, 2006).

In recent years, there has been increased awareness of impulsive-compulsive spectrum behaviors (ICBs) in PD, which are reward or incentive based, repetitive in nature, and have been linked to DRT (Gallagher et al, 2007; Ondo and Lai, 2008; Tippmann-Peikert et al, 2007). ICBs occur in a minority of PD patients administered DRT, but can nonetheless be extremely disabling and have a profound effect on patients' everyday function (Potenza et al, 2007). They include motor stereotypies, such as punding (repetitive, stereotypical, and mindless behavior, eg, collecting, arranging, or dismantling), appetitive behaviors, such as hypersexuality, pathological gambling (PG), compulsive shopping, and binge eating, (Voon and Fox, 2007), as well as the compulsive use of excessive DRT, termed ‘Dopamine Dysregulation Syndrome' (DDS: Lawrence et al, 2003). Patients with DDS show greatly enhanced drug-induced release of dopamine in the ventral striatum (Evans et al, 2006), a finding also seen in PD patients with PG during decision making (Steeves et al, 2009). However, the cognitive mechanisms underpinning ICBs remain poorly understood.

One possible mechanism contributing to the development of ICBs might be an alteration in the processing of stimuli associated with reward (conditioned stimuli: CS+). Dopamine release in the ventral striatum is believed to mediate the ‘incentive salience' of CS+, corresponding to their motivational value (Berridge and Robinson, 1998). In support of this hypothesis, CS+ elicit phasic dopamine firing in the midbrain when presented alone (Schultz et al, 1997), and the ability of a CS+ to invigorate responding (known as Pavlovian to instrumental transfer: PIT) seems to be modulated by ventral striatal dopamine (Wyvell and Berridge, 2000). Moreover, the administration of amphetamine and haloperidol, which are drugs that boost and block the effects of dopamine respectively, alters reward processing in humans (Knutson et al, 2004; Pessiglione et al, 2006). Therefore, it has been suggested that ICBs in PD may be related to an increase in the subjective estimation of the motivational value of stimuli, caused by excessive dopamine release in the ventral striatum (Steeves et al, 2009; van Eimeren and Siebner, 2006).

However, other cognitive mechanisms may contribute to the development of ICBs. A strong candidate is delay discounting, ie, the tendency to prefer sooner, smaller rewards over those that are larger but temporally more distant. Similar to incentive salience, delay discounting seems to be critically dependent on ventral striatal function (Cardinal et al, 2004; Pine et al, 2009). Delay discounting is reliably increased in other impulse-control disorders, such as substance abuse (Petry, 2002), and is affected both by acute administration of dopaminergic agents (Cardinal et al, 2000; Wade et al, 2000) and variation in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene (Boettiger et al, 2007). In support of this hypothesis, a recent study provided evidence of elevated discounting over short delays in PD patients with ICBs, but not those without ICBs, while taking DRT (Voon et al, 2010).

Understanding the mechanisms underpinning ICBs could potentially be important in predicting which patients might be vulnerable to developing them, or in developing new therapeutic strategies targeting them. Therefore, we investigated whether ICBs in patients with PD were associated with increased valuation of stimuli associated with reward, decreased tolerance to delay for rewards, or both. We used a reinforcement-learning paradigm, the salience attribution test (SAT) (Roiser et al, 2009), to index value learning, and the Kirby delayed discounting questionnaire to measure tolerance to delay (Kirby et al, 1999). We predicted that PD patients with ICBs (PD+ICB) would exhibit excessive value learning and delay discounting relative to PD patients without ICBs (PD−ICB) and controls. As DRT can induce psychotic symptoms in some PD patients, and as it has been hypothesized that excessive dopamine release in the ventral striatum contributes to the development of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia (Kapur, 2003), we also assessed schizotypy, a personality trait related to the risk for psychosis (Chapman et al, 1994). We predicted that PD+ICB patients would exhibit greater schizotypy scores than both PD−ICB patients and controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A total of 36 PD patients were recruited from the movement disorders clinic at The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery. All patients had been assessed by a neurologist before participation to identify ICBs and DDS using a structured interview and proposed ICB criteria (Evans et al, 2004; Giovannoni et al, 2000; Voon and Fox, 2007). Disease severity was also assessed by a neurologist using the Hoehn and Yahr scale (H&Y: Hoehn and Yahr, 1967). All patients were receiving DRT at the time of participation. They had taken their usual amounts of DRT, and were thus in an ‘on-medication' state while performing the tasks, although they were not instructed to take DRT at a specific time before testing. Calculation of a daily -dopa equivalent dose (LED) dose for each patient was based on theoretical equivalence of dopamine agonists to -dopa (Evans et al, 2004).

Clinical features of participants are presented in Table 1. Of the 18 PD+ICB patients, 9 had PG, 9 had binge eating, 8 had punding, 7 had hypersexuality, 6 had compulsive shopping, and 4 had DDS. The mean duration of ICBs was 4.13 years (SD 1.4 years). The researcher administrating the personality measures and cognitive tasks was blind to whether patients were in the PD−ICB or PD+ICB group. Patients were compared with 20 healthy controls, recruited through advertisement. Exclusion criteria for controls were known psychiatric or neurological disorder, intelligent quotient (IQ) <70, and illicit substance use within the past 12 months. The absence of axis-I psychopathology (save for a remote history of either depression or alcohol/substance abuse) was confirmed with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory in all participants (Sheehan et al, 1998).

Table 1. Demographic, Clinical, and Questionnaire Measures.

| Controls (n=20) | PD−ICB (n=18) | PD+ICB (n=18) | Statistic and p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 10/10 | 12/6 | 11/7 | χ2(2)=1.14, p=0.566 |

| Estimated full-scale IQ (WTAR) | 109.0 (8.5) | 109.8 (7.8) | 98.0 (12.7)a,b | F(2, 49)=6.90, p=0.002 |

| Age (years) | 65.5 (6.0) | 67.7 (5.5) | 62.3 (7.6)a,b | F(2, 52)=4.15, p=0.021 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 5.8 (4.3) | 11.3 (6.9)b | 12.9 (9.9)b | F(2, 52)=5.93, p=0.005 |

| State anxiety | 7.1 (5.0) | 14.3 (8.2)b | 18.3 (9.7)b | F(2, 52)=10.86, p<0.001 |

| Trait anxiety | 15.7 (8.7) | 17.9 (8.3) | 22.8 (11.1) | F(2, 52)=2.49, p=0.093 |

| Duration of PD (years) | 12.9 (8.3) | 13.9 (9.0) | t(33)=0.34, p=0.74 | |

| Total LDEU of all DRTs (mg) | 804.8 (358.5) | 891.5 (432.1) | t(34)=0.78, p=0.44 | |

| DA LDEU (mg) | 170.5 (159.3) | 248 (301.3) | t(34)=1.00, p=0.32 | |

| -dopa dose, mg | 634.2 (301.7) | 643.5 (254.1) | t(34)=0.24, p=0.81 | |

| H&Y | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.6) | t(33)=0.13, p=0.89 | |

| UPDRS III | 21.3 (10.4) | 20.0 (6.6) | t(26.9)=0.44, p=0.67 | |

| MMSE | 29.4 (0.8) | 28.6 (2.1) | t(21.6)=1.57, p=0.13 | |

| O-LIFE Unexplained Experiences | 1.2 (1.6) | 2.6 (2.1)b | 4.1 (2.6)b | F(2, 51)=8.08, p=0.001 |

| O-LIFE Cognitive Disorganisation | 3.1 (2.0) | 4.8 (2.3)b | 6.2 (2.8)b | F(2, 51)=8.82, p=0.001 |

| O-LIFE Introvertive Anhedonia | 1.6 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.9) | 3.7 (2.0)a,b | F(2, 51)=6.58, p=0.003 |

| O-LIFE Impulsive Nonconformity | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.9 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.2)a,b | F(2, 51)=3.64, p=0.033c |

| k—large reward | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.7) | 3.0 (4.3)a,b | F(2, 50)=5.27, p=0.008 |

| k—medium reward | 0.7 (0.9) | 1.3 (1.7) | 3.8 (4.1)a,b | F(2, 50)=6.56, p=0.003 |

| k—small reward | 1.4 (3.5) | 2.5 (3.9) | 6.8 (6.2)a,b | F(2, 50)=6.21, p=0.004 |

Abbreviations: DA, dopamine agonist; DRT, dopamine replacement therapy; H&Y, Hoehn and Yahr scale; IQ, intelligence quotient; k, hyperbolic discounting parameter derived from Kirby delayed discounting questionnaire; LDEU, -dopa equivalent units; MMSE, Mini Mental-State Examination; O-LIFE, Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences; WTAR, Weschler Test of Adult Reading.

Values are means (SD).

Different to PD−ICB group at p<0.05.

Different to control group at p<0.05.

Did not survive covariate analysis.

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent, were compensated £10 for their time and travel expenses, and could win up to another £20 on the SAT.

Questionnaire Measures

The Kirby delayed discounting questionnaire was used examine how participants rated future rewards (Kirby et al, 1999). Participants were presented a fixed set of 27 choices between smaller, immediate rewards, and larger, delayed rewards. For example, one question asked participants, ‘Would you prefer £54 today, or £55 in 117 days?,' while another asked, ‘Would you prefer £55 today, or £75 in 61 days?' The 27 questions were subdivided into 3 groups of 9 questions each, depending on the value of the delayed, larger reward offered, small (£25–£35), medium (£50–£60), and large (£75–£85) rewards. A future reward is typically valued less highly than the same reward available immediately (Madden et al, 1999). Therefore, delay discounting is the reduction in the present value of a future reward as the delay to that reward increases. The hyperbolic discount parameter (k) was calculated for each participant for high, low, and medium monetary rewards. As k increases, the person discounts the future more steeply. This hyperbolic function accurately models choices made by both human and nonhuman subjects (Green and Myerson, 2004; Myerson and Green, 1995; Rachlin et al, 1991). Therefore, k can be considered an impulsiveness parameter, with higher values corresponding to higher levels of impulsiveness (Herrnstein, 1970).

Schizotypy was assessed using the short scales of the Oxford–Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE) (Mason et al, 2005). The O-LIFE consists of four subscales: Unexplained Experiences (perceptual aberrations and magical thinking); Cognitive Disorganisation (poor attention, poor decision making, and social anxiety); Introvertive Anhedonia (avoidance of intimacy and lack of pleasure from social and physical stimuli); and Impulsive Nonconformity (impulsive and eccentric behaviors suggesting a lack of self-control). State and trait anxiety were assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger et al, 1970). The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to detect depression and assess the intensity of depression symptoms (Beck et al, 1988).

Salience Attribution Test

The SAT (Roiser et al, 2009; Schmidt and Roiser, 2009) taps the attribution of motivational salience to task-relevant and task-irrelevant stimulus dimensions. During the game, which is rewarded with real money, participants pressed a key in response to a black square (the probe) after seeing one of several cues, which varied along two dimensions (namely color and shape). The probability of reward varied along one of these dimensions (the task-relevant dimension—eg, color), but not the other (the task-irrelevant dimension—eg, shape). Participants' response times (implicit) and visual analog scale (VAS) ratings (explicit) provided measures of adaptive (task-relevant) and aberrant (task-irrelevant) salience attribution. In particular, the VAS ratings allow the estimation of the subjective value of stimuli to participants. Participants completed two practice sessions without cues or reward (20 trials each), followed by two experimental sessions (64 trials each).

Explicit adaptive salience was calculated as the increase in participants' VAS ratings of the probability of a stimulus to predict monetary reward for high-probability stimuli relative to low-probability stimuli. Explicit aberrant salience was calculated as the absolute difference in VAS rating between the two levels of the task-irrelevant dimension. Implicit adaptive salience was calculated as the speeding of responses on high-probability trials relative to low-probability trials. Implicit aberrant salience was defined as the absolute difference in reaction time between the two levels of the task-irrelevant stimulus dimension (Roiser et al, 2009).

Other Cognitive Tests

All participants were screened for cognitive impairment using the Mini Mental-State Examination (MMSE: Folstein et al, 1975). Those with scores under 26 on the MMSE were excluded from the study. IQ was estimated using the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (Wechsler, 2001), and working memory was tested using a shortened version of the forwards and backwards digit-span test (Wechsler, 1981).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Demographic measures of disease severity (H&Y), dopamine equivalent dose, and duration of PD were analyzed using independent samples t-tests. Gender distribution was analyzed using χ2 tests, and all other demographic data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Where a significant group effect was identified in a one-way ANOVA, post-hoc analyses were conducted using the least significance difference test.

SAT, digit span, and Kirby delayed discounting data were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA. For digit span, stage (forwards/backwards) was the within-subjects variable; for the Kirby, reward (high/low/medium) was the within-subjects variable; and for the SAT, the within subjects variables were block (1/2) and probability (high/low). Group (control/PD−ICB/PD+ICB) was the between-subjects variable in all analyses. Both implicit and explicit aberrant salience scores were square root transformed before analysis to reduce skew, although untransformed values are presented in the tables and figures for clarity. If significant nonsphericity was detected, degrees of freedom were adjusted using the Huynh–Feldt correction. Where a significant group × condition interaction was identified in a repeated-measures ANOVA, post-hoc analysis was conducted by examining the simple main and interaction effects, using t-tests or F-tests as appropriate. Where the homogeneity of variance constraint was satisfied, these post-hoc analyses included the pooled error term and degrees of freedom from the interaction effect.

Correlations between questionnaire, behavioral, and clinical variables were performed using Pearson's r. For all analyses, p<0.05 was considered significant, whereas 0.05<p<0.1 was considered a trend toward significance.

RESULTS

Demographic Data

The groups were well matched for gender but differed significantly in terms of age and IQ (Table 1). PD+ICB patients were significantly younger and had lower estimated IQ than did PD−ICB patients and controls. In view of the well-established influences of age and IQ on cognitive performance, all analyses were repeated, including age and IQ as covariates. However, unless otherwise stated, this did not change the results, and therefore all analyses presented below are without covariates.

Clinical Rating Scales

The PD−ICB group did not differ significantly from the PD+ICB group on BDI score, H&Y score, LED, or disease duration (Table 1). However, both patient groups had significantly higher BDI scores and STAI state anxiety scores than did controls.

Schizotypy

PD patients scored higher, with PD+ICB patients scoring the highest, on all the O-LIFE schizotypy subscales (Table 1): Unexplained Experiences (Control vs PD−ICB: p=0.035; Control vs PD+ICB: p=0.0002; PD−ICB vs PD+ICB: p=0.069); Cognitive Disorganisation (Control vs PD−ICB: p=0.010; Control vs PD+ICB: p=0.00014; PD−ICB vs PD+ICB: p=0.14); Introvertive Anhedonia (Control vs PD−ICB: p=0.183; Control vs PD+ICB: p=0.0007; PD−ICB vs PD+ICB: p=0.029); Impulsive Nonconformity (Control vs PD−ICB: p=0.833; Control vs PD+ICB: p=0.016; PD−ICB vs PD+ICB: p=0.030). However, the group effect on impulsive nonconformity was no longer significant when age and IQ were included as covariates (p=0.374).

Kirby Delayed Discounting

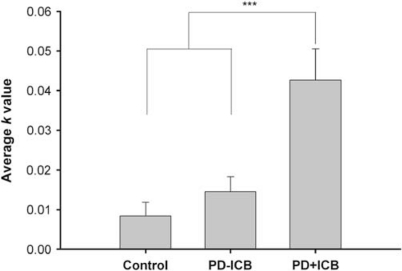

The groups differed significantly according to the k measure of delay aversion (F(2, 50)=11.89, p=0.00005, see Table 1 and Figure 1). Over all delays, the PD+ICB group scored significantly higher (indicating increased impulsivity) than did the PD−ICB (p=0.00068) and control (p=0.00002) groups, which did not differ (p=0.416). k decreased at higher reward magnitudes (F(1.64, 81.89)=7.67, p=0.001, ɛ=0.819), but there was no interaction between group and reward magnitudes (F(3.28, 81.89)=1.19, p=0.319; ɛ=0.819).

Figure 1.

Hyperbolic discounting measure, k, from the Kirby delay discounting questionnaire. PD+ICB patients were significantly less tolerant of delay than PD−ICB patients (p=0.00068) and control participants (p=0.00002), who did not differ (p=0.42). Values are means; error bars indicate SEM. ***p<0.001.

SAT

Behavioral data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Behavioral Data.

| Test | Controls | PD−ICB | PD+ICB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salience attribution test | |||

| Block 1 | |||

| RT high probability (ms) | 276.9 (39.6) | 342.6 (75.2) | 315.8 (90.7) |

| RT low probability (ms) | 285.7 (47.0) | 344.5 (81.8) | 322.1 (81.2) |

| Implicit adaptive salience (ms)a | 8.7 (28.1) | 1.9 (43.9) | 6.2 (39.5) |

| Implicit aberrant salience (ms)b | 21.2 (13.9) | 25.3 (29.5) | 32.0 (27.9) |

| VAS high probability (mm) | 47.9 (16.8) | 30.6 (19.7) | 45.7 (20.9) |

| VAS low probability (mm) | 20.1 (13.6) | 19.4 (11.7) | 26.6 (20.7) |

| Explicit adaptive salience (mm)a | 27.8 (24.9) | 11.3 (20.9) | 19.1 (30.0) |

| Explicit aberrant salience (mm)b | 13.8 (11.4) | 7.5 (8.9) | 11.8 (9.6) |

| Premature responses | 2.6 (1.7) | 5.3 (3.4) | 4.0 (3.4) |

| Omissions | 1.0 (2.3) | 2.8 (2.9) | 1.4 (0.8) |

| Block 2 | |||

| RT high probability (ms) | 259.7 (40.8) | 343.9 (110.8) | 330.5 (108.5) |

| RT low probability (ms) | 279.2 (55.6) | 332.0 (86.0) | 329.0 (85.1) |

| Implicit adaptive salience (ms)a | 19.5 (30.0) | −11.92 (46.2) | −1.5 (69.6) |

| Implicit aberrant salience (ms)b | 15.4 (14.5) | 25.7 (22.2) | 13.1 (9.6) |

| VAS high probability (mm) | 56.5 (22.4) | 27.0 (19.1) | 42.7 (19.7) |

| VAS low probability (mm) | 18.5 (10.6) | 17.2 (10.6) | 24.1 (16.6) |

| Explicit adaptive salience (mm)a | 38.0 (27.9) | 9.8 (20.9) | 18.6 (27.5) |

| Explicit aberrant salience (mm)b | 10.3 (9.2) | 6.7 (6.1) | 12.7 (11.3) |

| Premature responses | 2.5 (1.6) | 4.8 (3.7) | 3.9 (2.4) |

| Omissions | 0.8 (1.9) | 3.3 (5.1) | 2.8 (5.2) |

| Digit span | |||

| Forwards | 9.7 (2.3) | 8.6 (2.3) | 7.8 (1.7) |

| Backwards | 8.2 (2.2) | 6.9 (2.0) | 6.2 (2.1) |

Abbreviations: RT, reaction time; VAS, visual analog scale.

Values are means (SD).

Adaptive salience represents quicker responding or higher subjective reinforcement rating for high-probability trials relative to low-probability-reinforcement trials. For RT, adaptive salience is computed as: low-reinforcement-probability mean RT−high-reinforcement-probability mean RT. For VAS, adaptive salience is computed as: high-reinforcement-probability VAS rating−low-reinforcement VAS rating.

Aberrant salience is quicker responding to or higher subjective rating of one level of the task-irrelevant dimension relative to the other level. For RT, aberrant salience is computed as: irrelevant ‘low' RT−irrelevant ‘high' RT. For VAS, aberrant salience is computed as: irrelevant ‘high' VAS rating−irrelevant ‘low' VAS rating.

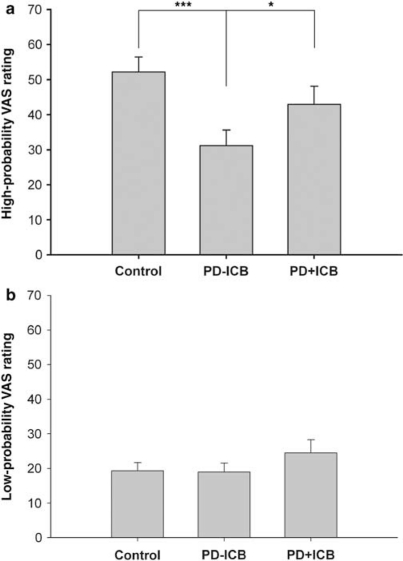

VAS (explicit salience)

Participants rated high-probability-reinforced stimuli as significantly more likely to yield reward than low-probability-reinforced stimuli, indicating that participants were able to learn the discrimination between the reward-probability levels (explicit adaptive salience: F(1, 53)=42.75, p<0.0001). Overall VAS rating differed significantly between the groups (F(2, 53)=4.75, p=0.013). However, these effects were qualified by a significant group × probability interaction (F(2, 53)=3.48, p=0.038). Explicit adaptive salience was significant in each group separately (controls: F(1, 19)=37.45, p<0.001; PD−ICB: F(1, 17)=7.23, p=0.016; PD+ICB: F(1, 17)=7.84, p=0.012). However, further analysis showed that the groups differed in terms of VAS rating for high-probability-reinforced stimuli (F(2, 53)=5.33, p=0.008; Figure 2a), but not for low-probability-reinforced stimuli (F(2, 53)=0.830, p=0.442; Figure 2b). The PD−ICB group rated high-probability-reinforced stimuli significantly less likely to yield reward than did the control group (p=0.0006) and the PD+ICB group (p=0.048). The control and PD+ICB groups did not differ in their rating of high-probability-reinforced stimuli (p=0.158).

Figure 2.

Visual analog scale (VAS) ratings for high- and low-probability-reinforced stimuli. (a) Both the control (p=0.0006) and the PD+ICB (p=0.048) groups rated high-probability-reinforced stimuli as significantly more likely to yield reward than the PD−ICB group, but did not differ from each other (p=0.158). (b) The groups did not differ in terms of VAS ratings for stimuli that had a low probability of being reinforced. Values are means; error bars indicate SEM. *p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

There was no main effect of block (F(1, 53), p=0.173); however, there was a significant block × group interaction (F(1, 53)=9.21, p=0.0003). In controls, VAS ratings increased significantly in the second block (F(1, 19)=9.45, p=0.006), whereas the reverse was true for the PD groups (PD−ICB: F(1, 17)=4.89, p=0.016; PD+ICB: F(1, 17)=6.16; p=0.024). No other interactions approached significance (p>0.1).

No significant effects were detected in the analysis of explicit aberrant salience (p>0.1 for all).

Reaction time (implicit salience)

The main effect of probability (F(1, 53)=1.46, p=0.232) and group × probability interaction (F(1, 53)=1.56, p=0.220) on RT was nonsignificant. However, planned comparisons showed that although controls exhibited significant implicit adaptive salience (ie, responding significantly faster on high-probability trials than on low-probability trials: F(1, 19)=6.72, p=0.018), PD patients did not (PD−ICB: F(1, 17)=0.301, p=0.590; PD+ICB: F(1, 17)=0.355, p=0.559). There was a main effect of group on overall RT, with the controls responding significantly faster than both patient groups, who did not differ from each other (F(2, 53)=4.55, p=0.015; controls vs PD+ICB: p=0.007; controls vs PD−ICB: p=0.026; PD+ICB vs PD−ICB: p=0.607). This difference was qualified by a significant group × block interaction (F(2, 53)=3.51, p=0.037), driven by faster responses on the second block in controls (F(1, 19)=6.04, p=0.024) but not in the patient groups (PD−ICB: F(1, 17)=0.45, p=0.510; PD+ICB: F(1, 17)=2.75, p=0.115). There was no overall main effect of block on RT, and no other interactions approached significance (p>0.1).

The groups did not differ in terms of implicit aberrant salience (F(2, 53)=0.461, p=0.633). Across all participants, implicit aberrant salience was higher on the first block (F(1, 53)=4.13, p=0.047), but the group × block interaction was nonsignificant (F(2, 53)=1.62, p=0.208).

Premature responses and omissions

Participants made more premature responses on high-probability trials compared with low-probability trials (F(1, 53)=9.18, p=0.004). The number of premature responses differed according to group (F(1, 53)=4.910, p=0.011), with controls making fewer premature responses than the PD−ICB (p=0.003) and PD+ICB (0.088) groups, which did not differ (p=0.183). No other main effects of interactions approached significance (p>0.1). No significant effects were detected in the analysis of omission errors (p>0.1).

Digit Span

Digit-span score differed according to group (F(1, 49)=4.68, p=0.014). Controls scored higher than both the PD−ICB (p=0.08) and PD+ICB (p=0.004) groups, which did not differ (p=0.247). Scores were lower in the backwards condition than in the forwards condition (F(1, 49)=43.4, p<0.0001), but the group × condition interaction was nonsignificant (F(1, 49)=0.493, p=0.757; see Table 2).

Correlations

O-LIFE

Across all participants, the O-LIFE Introvertive Anhedonia score was positively correlated with explicit aberrant salience (r=0.291, p=0.033), and the O-LIFE Cognitive Disorganisation score was positively correlated with implicit aberrant salience (r=0.31, p=0.019). The O-LIFE Introvertive Anhedonia score was positively correlated with k at the large reward (r=0.287, p=0.041) and medium reward (r=0.35, p=0.012) levels across all participants. However, the correlations between O-LIFE Introvertive Anhedonia and k were nonsignificant in each group separately. Across all PD patients, O-LIFE Impulsive Nonconformity was positively correlated with DA dose (in -dopa equivalent units) (r=0.45, p=0.008).

Dopamine replacement therapy

The daily LED of dopamine agonists, or -dopa, or daily total DRT used did not correlate with SAT or Kirby delayed discounting questionnaire results.

Digit span

Across all participants, the digit-span forward score was positively correlated with explicit adaptive salience (r=0.324, p=0.019), and the digit-span backward score was positively correlated with explicit adaptive (r=0.359, p=0.009) and explicit aberrant salience (r=0.347, p=0.012), and negatively correlated with implicit aberrant salience (r=−0.304, p=0.029) and k at the medium reward (r=−0.275, p=0.035).

DISCUSSION

We identified a double dissociation between reward learning and impulsivity in PD patients with and without ICBs. Relative to both PD−ICB patients and controls, PD+ICB patients exhibited greater delay discounting, suggesting decreased tolerance for delayed gratification, consistent with a recent finding (Voon et al, 2010). By contrast, PD+ICB patients exhibited similar scores on the explicit adaptive salience measure derived from the SAT to controls, with both these groups scoring higher than PD−ICB patients. This finding is consistent with other previous studies demonstrating impaired stimulus-reward learning in PD patients without ICBs (Bodi et al, 2009; Peterson et al, 2009; Rutledge et al, 2009; Swainson et al, 2000). The difference between the groups seemed to be driven by learning pertaining to high-probability-reinforced stimuli, as the groups rated low-probability-reinforced stimuli equally likely to be associated with reward. These data are consistent with an explanation of ICBs in terms of elevated impulsivity, but contradict the hypothesis that ICBs result from overvaluation of CS+ (Evans et al, 2006; Holden, 2001; Isaias et al, 2008; Tamminga and Nestler, 2006).

An explanation for decreased explicit adaptive salience in PD patients without ICBs may relate to depleted dopaminergic release to reward in the ventral striatum compared with healthy controls and PD+ICB (Evans et al, 2006; Steeves et al, 2009). This finding replicates past research that has shown reward-learning deficits in PD patients without ICBs (Czernecki et al, 2002; Swainson et al, 2000). In PD, the phasic release of dopamine that is normally associated with the presentation of a conditioned stimulus may be reduced, impairing the ability to form associations between stimuli and rewards (Rescorla and Wagner, 1972). Consistent with this suggestion, experimental studies in healthy volunteers have shown that administration of haloperidol (a dopamine antagonist) impairs the ability to learn to choose rewarding actions and decreases ventral striatal responses elicited by reward prediction errors (Pessiglione et al, 2006; Pleger et al, 2009). By contrast, patients with ICBs were able to learn the dissociation between high-probability and low-probability reward predicting stimuli, as well as controls. This suggests that elevated dopamine transmission in these patients may have ameliorated the reward-learning deficit. Therefore, although PD+ICB patients experience disruptive drug-induced behavioral symptoms, they can perform as well as controls at learning stimulus–reward associations, and importantly did not seem to overvalue stimuli associated with reward.

PD+ICB patients were significantly more impulsive than the other two groups, with greatly elevated k values on the Kirby delay discounting questionnaire. This result is consistent with another recent study that used a different method to assess delay discounting over shorter timescales in PD patients with and without ICBs (Voon et al, 2010). Similar findings have also been reported in several studies involving substance abusers, including cigarette smokers (Mitchell, 1999; Odum et al, 2002), alcoholics (Petry, 2001), and heroin addicts (Kirby et al, 1999; Madden et al, 1999). Rates of delay discounting correlate with personality questionnaires of impulsivity (Kirby et al, 1999; Petry, 2001), suggesting that delay discounting taps some construct of impulsivity.

It is possible that high levels of impulsivity in these patients result from excessive dopaminergic transmission in the orbitalfrontal cortex (OFC: Cools, 2006), to which the ventral striatum projects. Frontal lesions in experimental animals result in a preference for immediate small rewards over delayed larger rewards (Mobini et al, 2002), as well as with other disinhibited behaviors (Roesch et al, 2007). Studies using in vivo microdialysis have shown increases in dopamine release in the OFC during the performance of delay-discounting tasks in rats (Winstanley et al, 2006). Interestingly, a recent study reported that administration of pramipexole diminished OFC sensitivity during a decision-making task in PD patients, specifically reducing de-activations elicited by negative prediction errors (van Eimeren et al, 2009). However, this study only included PD patients without ICBs, limiting comparison with this study.

Alternatively, the preference for sooner, smaller rewards in PD patients with ICBs could be mediated by altered dopaminergic transmission in the ventral striatum itself, as studies in both rats and humans suggest that this structure has a central role in encoding information relating to delays (Cardinal et al, 2001; Pine et al, 2009). Either way, the pattern of decreased tolerance to delay in tandem with intact stimulus-reinforcement learning suggests that ICBs are mediated by increased impulsivity and not overvaluation of rewards. Future studies using functional neuroimaging measures would help to elucidate the neurobiological mechanisms underpinning this pattern of results; specifically, it would be of great interest to use tasks that can dissociate neural responses associated with delay discounting from those associated with reward magnitude (see Pine et al, 2009). As impulsivity is a multidimensional construct (Evenden, 1999), it would also be of interest in future studies to examine whether PD patients with ICBs are more impulsive in other domains behavior, such as motor inhibitory control and risky decision making (Rossi et al, 2010).

The usual treatment for ICBs is to reduce the dose of dopaminergic medication as there is some evidence to suggest that this is associated with the development of ICBs (Lee et al, 2010). However, this is often unsatisfactory for the patient because it can worsen motor control. The finding that this group was specifically more impulsive has potentially important clinical implications as recent findings in other impulse-control disorders suggest that this can be treated with nondopaminergic medication. For example, impulsivity in these patients might be ameliorated by drugs with noradrenergic actions, such as atomoxetine, which have been shown to improve response inhibition (Chamberlain et al, 2009) and effectively treat impulsive features in certain psychiatric disorders, such as ADHD (Chamberlain et al, 2007).

Consistent with the notion that cognitive impairment and maladaptive behavior after DRT in PD result from an ‘overdosing' effect on dopaminergic transmission in the ventral striatum, PD patients exhibited significantly increased scores on the O-LIFE schizotypy scales, which tap personality traits relating to psychosis. Although psychotic reactions after DRT have been reported previously in some patients with PD, to our knowledge this is the first report of generally elevated schizotypy scores. This elevation was exaggerated in PD+ICB patients, who scored significantly higher than the PD−ICB group on the ‘Introvertive Anhedonia' and ‘Impulsive Non-conformity' subscales (although this effect was nonsignificant when age and IQ were included as covariates), with a trend toward greater scores on the ‘Unexplained Experiences' subscale. The latter of these assesses experiences relating to psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions. These data suggest that low-level psychotic experiences may be a relatively common side effect of DRT, especially in PD+ICB patients, even in those who do not experience full-blown psychosis. This finding is also consistent with the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia and related theories, which propose a central role for dysregulated dopaminergic transmission in the instantiation and maintenance of both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Juckel et al, 2006; Kapur, 2003; Roiser et al, 2009; Ziauddeen and Murray, 2010). However, despite elevated schizotypy in PD+ICB patients, aberrant salience scores derived from the SAT did not differ between the groups, although schizotypy and aberrant salience were correlated across all participants, replicating our previous findings (Roiser et al, 2009; Schmidt and Roiser, 2009). The relationship between psychotic symptoms in PD, DRT, and aberrant salience warrants further investigation in future studies.

Both PD groups were impaired on the implicit adaptive salience measure derived from the SAT, indicating that they failed to speed responses on trials in which reward was very likely relative to when it was improbable. Implicit adaptive salience scores were similar in the PD−ICB and PD+ICB groups, despite the relatively normal explicit adaptive scores in the PD+ICB group. This latter finding is evidence against the explanation that impaired implicit adaptive salience in PD patients resulted from a learning deficit. Instead, a more likely explanation is that, at least in the PD+ICB group, patients were unable to use cue values to guide speeded responding. Importantly, studies in experimental animals have shown that dopamine transmission in the ventral striatum has a central role in the invigoration of responding after the presentation of CS+ (known as PIT: Berridge and Robinson, 1998). Impairment in reward-elicited speeding in PD patients, in whom dopamine transmission is disrupted, may thus reflect dysfunction of a similar mechanism. However, it should be acknowledged that both PD groups were impaired on other indices on the SAT: neither group improved on explicit adaptive salience from block 1 to block 2, which could be considered evidence of a learning deficit; and both made more premature responses, although this finding may simply reflect a motor deficit.

PD patients were also impaired on the digit-span test of working memory independent of ICB status, consistent with previous findings (Brown and Marsden, 1988; Cooper et al, 1991; Dubois and Pillon, 1997; Lewis et al, 2005; Owen et al, 1992). Experiments in animals have demonstrated a critical role for prefrontal cortex dopamine release in working memory, raising the possibility that this deficit is similarly related to disrupted dopamine transmission in PD (Floresco and Phillips, 2001; Sawaguchi and Goldman-Rakic, 1994; Williams and Goldman-Rakic, 1995; Zahrt et al, 1997). As we only tested participants while they were on medication, it is difficult to know whether these deficits are related to the reduced dopaminergic transmission associated with PD per se, or to an overdosing effect of DRT on components of the dopamine system spared by PD (Cools, 2006). Either way, our data underscore the difficulty of ameliorating cognitive deficits in PD with DRT, and emphasize the need for novel treatment strategies in this domain.

A limitation of our study is that PD+ICB patients were younger and of lower IQ than the other two groups, raising the possibility that the differences between PD patients with and without ICBs could be explained by nonspecific cognitive impairments. In addition, it is possible that other clinical concomitants of PD may have affected our results. However, we consider these explanations to be unlikely for two reasons. First, working memory, depression, anxiety, PD symptoms, duration of illness, and medication level were all well matched between the two PD groups. Second, and most importantly, statistically accounting for differences in age and IQ did not change our results, other than on one subscale of the O-LIFE schizotypy questionnaire.

A further limitation is that we did not recruit a sufficiently large sample of PD patients to allow meaningful statistical analysis of specific ICB subgroups. It is not yet known whether different kinds of ICBs may have different underlying neural and behavioral mechanisms. For example, some patterns of behavior included in the definition of ICBs may reflect compulsiveness (eg, punding) rather than impulsiveness (eg, DDS). Future studies should aim to recruit larger samples of PD patients with ICBs to explore this question further.

In summary, we found that PD patients without ICBs were impaired at learning stimulus–reward associations, replicating previous findings (Peterson et al, 2009; Rutledge et al, 2009; Swainson et al, 2000). Strikingly, however, PD patients with ICBs were unimpaired at learning stimulus–reward associations compared with those without ICBs, which may relate to relatively preserved striatal dopamine transmission. Rather, increased impulsivity as demonstrated by elevated delay discounting, seems to be a prominent feature of PD+ICB patients. Impulsive symptoms identified by neuropsychological tasks, such as the stop signal task, have previously been related to impulsive behaviors in everyday life (Chamberlain and Sahakian, 2007). It is important to note that our PD patients with and without ICBs were well matched for daily DRT used, and that DRT amounts did not correlate with delay discounting or aberrant salience. This suggests that a subgroup of patients are more sensitive to the behavioral effects of DRT and go on to develop ICBs, as opposed to a dose effect of DRT influencing behavior in PD. Therefore, further investigations of impulsivity may lead to better diagnostic classification systems for ICBs and novel treatments for these medication-induced disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the volunteers who participated in this study.

Jonathan P Roiser is a consultant for Cambridge Cognition and has received support from St Jude Medical for conference attendance. Sean S O'Sullivan has received honoraria from Brittania Pharmaceuticals. Andrew J Lees is a consultant for Genus. He sits on the advisory boards of Novartis, Teva, Meda, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Ipsen, Lundbeck, Allergan, and Orion and has received honoraria from all these companies. The other authors declare that they have no financial interests to disclose.

References

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer H, Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O, Jellinger K, Seitelberger F. Brain dopamine and the syndromes of Parkinson and Huntington. Clinical, morphological and neurochemical correlations. J Neurol Sci. 1973;20:415–455. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(73)90175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;28:309–369. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodi N, Keri S, Nagy H, Moustafa A, Myers CE, Daw N, et al. Reward-learning and the novelty-seeking personality: a between- and within-subjects study of the effects of dopamine agonists on young Parkinson's patients. Brain. 2009;132:2385–2395. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettiger CA, Mitchell JM, Tavares VC, Robertson M, Joslyn G, D'Esposito M, et al. Immediate reward bias in humans: fronto-parietal networks and a role for the catechol-O-methyltransferase 158(Val/Val) genotype. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14383–14391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2551-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RG, Marsden CD. ‘Subcortical dementia': the neuropsychological evidence. Neuroscience. 1988;25:363–387. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal RN, Pennicott DR, Sugathapala CL, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Impulsive choice induced in rats by lesions of the nucleus accumbens core. Science. 2001;292:2499–2501. doi: 10.1126/science.1060818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal RN, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. The effects of d-amphetamine, chlordiazepoxide, alpha-flupenthixol and behavioural manipulations on choice of signalled and unsignalled delayed reinforcement in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;152:362–375. doi: 10.1007/s002130000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal RN, Winstanley CA, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Limbic corticostriatal systems and delayed reinforcement. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1021:33–50. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Del Campo N, Dowson J, Muller U, Clark L, Robbins TW, et al. Atomoxetine improved response inhibition in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Hampshire A, Muller U, Rubia K, Del Campo N, Craig K, et al. Atomoxetine modulates right inferior frontal activation during inhibitory control: a pharmacological functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychiatry of impulsivity. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:255–261. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280ba4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Kwapil TR, Eckblad M, Zinser MC. Putatively psychosis-prone subjects 10 years later. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103:171–183. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R. Dopaminergic modulation of cognitive function-implications for L-DOPA treatment in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA, Sagar HJ, Jordan N, Harvey NS, Sullivan EV. Cognitive impairment in early, untreated Parkinson's disease and its relationship to motor disability. Brain. 1991;114 (Part 5:2095–2122. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czernecki V, Pillon B, Houeto JL, Pochon JB, Levy R, Dubois B. Motivation, reward, and Parkinson's disease: influence of dopatherapy. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:2257–2267. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Pillon B. Cognitive deficits in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 1997;244:2–8. doi: 10.1007/pl00007725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AH, Katzenschlager R, Paviour D, O'Sullivan JD, Appel S, Lawrence AD, et al. Punding in Parkinson's disease: its relation to the dopamine dysregulation syndrome. Mov Disord. 2004;19:397–405. doi: 10.1002/mds.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AH, Pavese N, Lawrence AD, Tai YF, Appel S, Doder M, et al. Compulsive drug use linked to sensitized ventral striatal dopamine transmission. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:852–858. doi: 10.1002/ana.20822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:348–361. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114 (Part 5:2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Phillips AG. Delay-dependent modulation of memory retrieval by infusion of a dopamine D1 agonist into the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:934–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state'. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher DA, O'Sullivan SS, Evans AH, Lees AJ, Schrag A. Pathological gambling in Parkinson's disease: risk factors and differences from dopamine dysregulation. An analysis of published case series. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1757–1763. doi: 10.1002/mds.21611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni G, O'Sullivan JD, Turner K, Manson AJ, Lees AJ. Hedonistic homeostatic dysregulation in patients with Parkinson's disease on dopamine replacement therapies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:423–428. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.4.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J. A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:769–792. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ. On the law of effect. J Exp Anal Behav. 1970;13:243–266. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1970.13-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden C. ‘Behavioral' addictions: do they exist. Science. 2001;294:980–982. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5544.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaias IU, Siri C, Cilia R, De Gaspari D, Pezzoli G, Antonini A. The relationship between impulsivity and impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:411–415. doi: 10.1002/mds.21872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juckel G, Schlagenhauf F, Koslowski M, Wustenberg T, Villringer A, Knutson B, et al. Dysfunction of ventral striatal reward prediction in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2006;29:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:13–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Bjork JM, Fong GW, Hommer D, Mattay VS, Weinberger DR. Amphetamine modulates human incentive processing. Neuron. 2004;43:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AD, Evans AH, Lees AJ. Compulsive use of dopamine replacement therapy in Parkinson's disease: reward systems gone awry. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:595–604. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00529-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Kim JM, Kim JW, Cho J, Lee WY, Kim HJ, et al. Association between the dose of dopaminergic medication and the behavioral disturbances in Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2009;373:2055–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60492-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SJ, Slabosz A, Robbins TW, Barker RA, Owen AM. Dopaminergic basis for deficits in working memory but not attentional set-shifting in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Bickel WK, Jacobs EA. Discounting of delayed rewards in opioid-dependent outpatients: exponential or hyperbolic discounting functions. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:284–293. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason O, Linney Y, Claridge G. Short scales for measuring schizotypy. Schizophr Res. 2005;78:293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:455–464. doi: 10.1007/pl00005491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobini S, Body S, Ho MY, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E, Deakin JF, et al. Effects of lesions of the orbitofrontal cortex on sensitivity to delayed and probabilistic reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;160:290–298. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L. Discounting of delayed rewards: models of individual choice. J Exp Anal Behav. 1995;64:263–276. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Madden GJ, Bickel WK. Discounting of delayed health gains and losses by current, never- and ex-smokers of cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:295–303. doi: 10.1080/14622200210141257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondo WG, Lai D. Predictors of impulsivity and reward seeking behavior with dopamine agonists. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2008;14:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, James M, Leigh PN, Summers BA, Marsden CD, Quinn NP, et al. Fronto-striatal cognitive deficits at different stages of Parkinson's disease. Brain. 1992;115 (Part 6:1727–1751. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.6.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessiglione M, Seymour B, Flandin G, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Dopamine-dependent prediction errors underpin reward-seeking behaviour in humans. Nature. 2006;442:1042–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature05051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson DA, Elliott C, Song DD, Makeig S, Sejnowski TJ, Poizner H. Probabilistic reversal learning is impaired in Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. 2009;163:1092–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;154:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers: relationship to antisocial personality disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;162:425–432. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine A, Seymour B, Roiser JP, Bossaerts P, Friston KJ, Curran HV, et al. Encoding of marginal utility across time in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9575–9581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1126-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleger B, Ruff CC, Blankenburg F, Kloppel S, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Influence of dopaminergically mediated reward on somatosensory decision-making. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN, Voon V, Weintraub D. Drug Insight: impulse control disorders and dopamine therapies in Parkinson's disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3:664–672. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Raineri A, Cross D. Subjective probability and delay. J Exp Anal Behav. 1991;55:233–244. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.55-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Wagner AR.1972A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcementIn: Black AH, Prokasy WF (eds).Classical conditioning II: Current Research and Theory Appelton-Century-Crofts: New York; 64–99. [Google Scholar]

- Roesch MR, Calu DJ, Burke KA, Schoenbaum G. Should I stay or should I go? Transformation of time-discounted rewards in orbitofrontal cortex and associated brain circuits. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1104:21–34. doi: 10.1196/annals.1390.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roiser JP, Stephan KE, den Ouden HE, Barnes TR, Friston KJ, Joyce EM. Do patients with schizophrenia exhibit aberrant salience. Psychol Med. 2009;39:199–209. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Gerschcovich ER, de Achaval D, Perez-Lloret S, Cerquetti D, Cammarota A, et al. Decision-making in Parkinson's disease patients with and without pathological gambling. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge RB, Lazzaro SC, Lau B, Myers CE, Gluck MA, Glimcher PW. Dopaminergic drugs modulate learning rates and perseveration in Parkinson's patients in a dynamic foraging task. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15104–15114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3524-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaguchi T, Goldman-Rakic PS. The role of D1-dopamine receptor in working memory: local injections of dopamine antagonists into the prefrontal cortex of rhesus monkeys performing an oculomotor delayed-response task. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:515–528. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K, Roiser JP. Assessing the construct validity of aberrant salience. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:58. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.058.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. 1998The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10 J Clin Psychiatry 59(Suppl 2022–33.quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Steeves TD, Miyasaki J, Zurowski M, Lang AE, Pellecchia G, Van Eimeren T, et al. Increased striatal dopamine release in Parkinsonian patients with pathological gambling: a [11C] raclopride PET study. Brain. 2009;132:1376–1385. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swainson R, Rogers RD, Sahakian BJ, Summers BA, Polkey CE, Robbins TW. Probabilistic learning and reversal deficits in patients with Parkinson's disease or frontal or temporal lobe lesions: possible adverse effects of dopaminergic medication. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:596–612. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA, Nestler EJ. Pathological gambling: focusing on the addiction, not the activity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:180–181. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tippmann-Peikert M, Park JG, Boeve BF, Shepard JW, Silber MH. Pathologic gambling in patients with restless legs syndrome treated with dopaminergic agonists. Neurology. 2007;68:301–303. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252368.25106.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eimeren T, Ballanger B, Pellecchia G, Miyasaki JM, Lang AE, Strafella AP. Dopamine agonists diminish value sensitivity of the orbitofrontal cortex: a trigger for pathological gambling in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2758–2766. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.npp2009124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eimeren T, Siebner HR. An update on functional neuroimaging of parkinsonism and dystonia. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:412–419. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000236623.68625.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V, Fox SH. Medication-related impulse control and repetitive behaviors in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1089–1096. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.8.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V, Reynolds B, Brezing C, Gallea C, Skaljic M, Ekanayake V, et al. Impulsive choice and response in dopamine agonist-related impulse control behaviors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;207:645–659. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1697-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade TR, de Wit H, Richards JB. Effects of dopaminergic drugs on delayed reward as a measure of impulsive behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;150:90–101. doi: 10.1007/s002130000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised. The Psychological Corporation: New York; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading Manual. The Psychological Cooperation: San Antonio, TX; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Modulation of memory fields by dopamine D1 receptors in prefrontal cortex. Nature. 1995;376:572–575. doi: 10.1038/376572a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley CA, Theobald DE, Dalley JW, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW. Double dissociation between serotonergic and dopaminergic modulation of medial prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex during a test of impulsive choice. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:106–114. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyvell CL, Berridge KC. Intra-accumbens amphetamine increases the conditioned incentive salience of sucrose reward: enhancement of reward ‘wanting' without enhanced ‘liking' or response reinforcement. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8122–8130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08122.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahrt J, Taylor JR, Mathew RG, Arnsten AF. Supranormal stimulation of D1 dopamine receptors in the rodent prefrontal cortex impairs spatial working memory performance. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8528–8535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08528.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziauddeen H, Murray GK. The relevance of reward pathways for schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:91–96. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328336661b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]