Abstract

Antipsychotic-induced weight gain has emerged as a serious complication in the treatment of patients with atypical antipsychotic drugs. The cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) is expressed centrally in the hypothalamic region and associated with appetite and satiety, as well as peripherally. An antagonist of CNR1 (rimonabant) has been effective in causing weight loss in obese patients indicating that CNR1 might be important in antipsychotic-induced weight gain. Twenty tag SNPs were analyzed in 183 patients who underwent treatment (with either clozapine, olanzapine, haloperidol, or risperidone) for chronic schizophrenia were evaluated for antipsychotic-induced weight gain for up to 14 weeks. The polymorphism rs806378 was nominally associated with weight gain in patients of European ancestry treated with clozapine or olanzapine. ‘T' allele carriers (CT+TT) gained more weight (5.96%), than the CC carriers (2.76%, p=0.008, FDR q-value=0.12). This translated into approximately 2.2 kg more weight gain in patients carrying the T allele than the patients homozygous for the CC genotype (CC vs CT+TT, 2.21±4.51 vs 4.33±3.89 kg; p=0.022). This was reflected in the allelic analysis (C vs T allele, 3.84 vs 5.83%, p=0.035). We conducted electrophoretic mobility shift assays which showed that the presence of the T allele created a binding site for arylhydrocarbon receptor translocator (ARNT), a member of the basic helix–loop–helix/Per–Arnt–Sim protein family. In this study, we provide evidence that the CNR1 gene may be associated with antipsychotic-induced weight gain in chronic schizophrenia patients. However, these observations were made in a relatively small patient population; therefore these results need to be replicated in larger sample sets.

Keywords: CNR1, clozapine, olanzapine, weight gain, genetics, association

INTRODUCTION

The use of atypical antipsychotic drugs (AADs) for treatment of schizophrenia has increased and they now capture over 90% of the antipsychotic drug market. Unlike the typical antipsychotic drugs, AADs have the primary advantage of being associated with very low or negligible risk of inducing extrapyramidal symptoms. However, one of the major concerns with AADs is the development of weight gain leading to full metabolic syndrome and early cardiac death (reviewed by Muller and Kennedy, 2006). Obesity in the general population has become a major public health challenge and association of AADs with weight gain adds another dimension to this problem.

The development of antipsychotic induced weight gain in a subset of schizophrenia patients (∼30%), concordance among twins, and high heritability of weight gain suggest a strong genetic component. Two polymorphisms, −759C/T in the serotonin receptor 5-HT2C, and the −2548 G>A promoter polymorphism in the leptin gene, are most consistently associated with antipsychotic-induced weight gain (eg, De Luca et al, 2007; Ellingrod et al, 2007; Templeman et al, 2005; Zhang et al, 2003). Other gene findings have been reviewed elsewhere (Muller and Kennedy, 2006). However, it is more than plausible to assume that, as for other complex inherited phenotypes, numerous and yet undiscovered genetic markers are involved in antipsychotic-induced weight gain.

The cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1 or CB1) is a seven transmembrane G-coupled receptor (Gi/o, Gs or Gq/11), expressed widely in several brain regions associated with reward, hunger, appetite and satiety and in peripheral tissues including the gut, liver (hepatocytes), adipocytes, skeletal muscle and pancreas (Ameri et al, 1999; Matias and Di Marzo, 2007; Woods, 2007). CNR1 knockout mice present a lean phenotype (Cota et al, 2003; Di Marzo et al, 2001), reduced food intake and resistance to diet-induced obesity (Osei-Hyiaman et al, 2005; Ravinet Trillou et al, 2003, 2004). Similarly, administration of rimonabant, a CNR1 receptor antagonist, leads to reduced food intake, decreased bodyweight, normalized plasma leptin, insulin, free fatty acids and corrected insulin resistance in wild-type animals (Jamshidi and Taylor, 2001; Ravinet Trillou et al, 2003). Conversely, injection of endogenous ligands of CNR1, such as anandamide or 2-arachidonoylglycerol, into the hypothalamus of pre-satiated rats increases dietary food intake. Furthermore, this increase in food intake could be prevented by pretreatment of the rats with rimonabant (Jamshidi and Taylor, 2001; Kirkham et al, 2002). Weston-Green et al (2008) showed that chronic administration of olanzapine decreases the binding of the agonist, [3H] CP-55940, to CNR1 in the dorsal vagal complex of the brain stem and causes increased weight gain in rats, whereas haloperidol failed to elicit similar effects. In humans, treatment of AIDS and cancer-related anorexia with dronabinol, a CNR1 agonist, leads to significant increase in appetite and body weight compared with placebo (Beal et al, 1995; Nelson et al, 1994). Furthermore, increased CNR1 mRNA levels in visceral adipose tissue of overweight and metabolic syndrome patients have been reported (Sarzani et al, 2009). In addition, hepatic stimulation of the CNR1 receptor leads to increased lipogenesis through augmented expression of the lipogenic transcription factor SREBP-1c (sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c), an effect inhibited by treatment with rimonabant (Osei-Hyiaman et al, 2005).

At the molecular level, CNR1 interacts with several molecules in the hypothalamus. For example CNR1 downregulates anorexigenic molecules such as cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript in the arcuate nucleus and corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) in the paraventricular nucleus. CNR1 also upregulates orexigenic neuropeptide Y and melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) in the lateral hypothalamus (Cota et al, 2003; Gamber et al, 2005; Osei-Hyiaman et al, 2005). Some of the effects of CNR1 are under regulation of leptin, which prevents the release of orexigenic and anorexigenic molecules (MCH and CRH, respectively; for detailed review see (Kunos, 2007; Matias and Di Marzo, 2007; Woods, 2007). Similarly, ghrelin is known to exert its orexigenic effects at least in part through CNR1 (Kola et al, 2008).

The CNR1 gene is located on 6q14–15, and a common polymorphism in intron 2, rs20232239, has been associated with obesity in the general population (Benzinou et al, 2008) as well as with substance dependence and CNR1 mRNA levels (Zhang et al, 2004). Furthermore, the C allele of this polymorphism has been associated with greater CB1 binding in the prefrontal cortex and alcohol cue-elicited brain activation (Hutchison et al, 2008).

Based on the above studies, the CNR1 gene represents a compelling candidate for genetic studies of antipsychotic-induced weight gain. In this study, we analyzed 20 tag polymorphisms in the CNR1 gene, including the synonymous polymorphism rs1049353 (1359 G>A, Thr453Thr) and obesity-associated rs20232239 for involvement in antipsychotic-induced weight gain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

A total of 183 patients with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were included in this study. Approval from the institutional ethics committee and informed consent were obtained for all patients. The details of the sample are provided in Table 1. Patients were recruited at three different sites: Sample A: Charite University Medicine, Berlin, Germany (DJ Müller and I Puls, n=47). Patients 18–60 years old diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to DSM-IV criteria were included. Other inclusion criteria were a minimum positive and negative symptom scale (PANSS) score of 60 and admission either due to first manifestation or relapse of pre-existent condition with significant deterioration. Patients were given antipsychotic medication and assessed up to 6 weeks (Table 1). Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or breast feeding, organic brain disorder or severe head injuries, severe or unstable comorbid medical conditions (Hepatitis C, HIV, Thyroid disorder, diabetes mellitus), and not stable, substance dependence (polytoxicomania), clinically relevant mental retardation, and severe personality disorder.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients Under Study.

| Characteristics | Sample Aa n=47 n (%) | Sample Ba n=79 n (%) | Sample Ca n=57 n (%) | Total n=183 n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 25 (53.2) | 51 (64.6) | 48 (84.2) | 124 (67.8) | 0.002 |

| Female | 22 (46.8) | 28 (35.4) | 9 (15.8) | 59 (32.2) | |

| Age (years) | 35.96±12.19 | 33.08±8.40 | 40.47±9.13 | 36.12±10.17 | <0.001 |

| Initial bodyweight (kg) | 79.40±15.85 | 74.73±13.71 | 84.94±17.41 | 79.01±15.97 | 0.001 |

| Weight change (kg) | 3.91±4.10 | 3.68±4.41 | 4.43±6.44 | 3.97±5.02 | 0.701 |

| Weight change (%) | 4.76±4.79 | 5.14±6.29 | 5.73±8.39 | 5.23±6.66 | 0.958b |

| Baseline BPRSc | 50.74±14.15 | 51.03±14.09 | 54.01±7.68 | 51.96±12.33 | 0.023b |

| Study duration (week) | 5.28±1.41 | 6.00 | 11.57±3.94 | 7.54±3.55 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| European-American | 47 (100) | 57 (72.2) | 13 (27.8) | 117 (63.9) | <0.001 |

| African-American | 0 | 22 (27.8) | 33 (57.9) | 55 (30.1) | |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 11 (19.3) | 11 (6.0) | |

| Drugs prescribed | |||||

| Clozapine | 10 (21.3) | 79 (100) | 12 (21.1) | 101 (55.2) | |

| Haloperidol | 0 | 0 | 12 (21.1) | 12 (6.6) | |

| Olanzapine | 12 (25.5) | 0 | 22 (38.6) | 34 (18.6) | |

| Risperidone | 25 (53.2) | 0 | 11 (19.3) | 36 (19.7) | |

The samples were included from three different clinical studies.

Kruskal–Wallis test.

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Baseline BPRS scores were not available for a subset of the patients (21/183). To achieve comparability with sample B, BPRS total scores were extracted from PANSS ratings for samples A and C.

Sample B: Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio (HY Meltzer, JA Lieberman, n=79). Patients 18–60 years old diagnosed with schizophrenia according to DSMIIR criteria who were either treatment refractory or intolerant to treatment with typical antipsychotics were included. Before starting treatment with clozapine there was a washout period of 7–14 days during which patients received no medications unless it was clinically essential. Clozapine dosage was not fixed and serum levels were monitored to ascertain compliance. Patients were treated with clozapine for 6 weeks and percent change in weight was calculated from baseline weight (for details see (Masellis et al, 1998)). Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, organic brain disorder or severe head injuries, previous medical conditions (Hepatitis C, HIV, Thyroid disorder, diabetes mellitus), which require treatment and are not stable, substance dependence (polytoxicomania), clinically relevant mental retardation and severe personality disorder.

Sample C: Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, New York (JA Lieberman, n=57). Patients 18–60 years old, with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to DSM-IV were included. These patients had shown suboptimal response to previous treatment with typical antipsychotic drugs, mainly defined by persistent positive symptoms and a poor level of functioning over the past 2 years. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either clozapine (500 mg/day), olanzapine (20 mg/day), risperidone (8 mg/day) or haloperidol in a 14-week double-blind study. Patients with a history of non-response to clozapine, risperidone, or olanzapine, defined as an unambiguous lack of improvement despite a contiguous adequate trial of risperidone or olanzapine for at least 6 weeks, or clozapine for at least 14 weeks were excluded. Similarly, patients with a history of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol intolerance as well as those who received a depot antipsychotic within 30 days before randomization were also excluded (for details see (Volavka et al, 2002)). Sample B and C have been described in more detail in previous studies (Basile et al, 2002; De Luca et al, 2007; Muller et al, 2005a, 2005b).

Ethnicity was determined using ancestry information provided by the participants. Patients were classified for ethnicity by assessing ancestry over last three generations.

Genetic Analysis

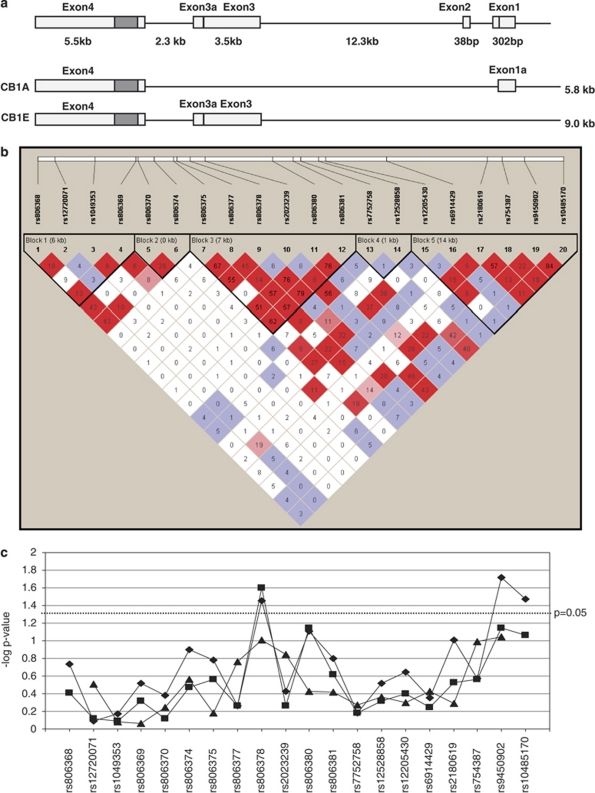

10 ml of venous blood was obtained from study participants and DNA was extracted at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health using the high salt method (Lahiri and Nurnberger, 1991). All the genotyping was carried out using TaqMan SNP genotyping assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Genotype calling was confirmed by two independent researchers and 5% of the total sample was re-genotyped to assure concordance. The concordance rate for this study was 99.86% and discordant genotypes were treated as missing in the statistical analysis. A total of 20 tagSNPs covering ∼32,500 bp and representing 100% of the common variation in the CNR1 gene region (minor allele frequency >0.05) were included in the study (Figure 1). Among the 20 SNPs rs806381, rs2023239, rs9450902 and rs10485170 were force-included as they were recently reported to be associated with weight gain in the general population (Benzinou et al, 2008).

Figure 1.

CNR1 gene structure, linkage disequilibrium observed and the results of association analysis. (a) Gene structure of CNR1. Alternative splicing is known to occur at CNR1 and five transcripts have been identified (Zhang et al, 2004). The two most common transcripts are shown. The gray filled boxes represent the coding region. (b) Linkage disequilibrium among the 20 tag SNPs tested and their location. Standard color scheme is used (Haploview 4.0). Please refer to the online version of the article for the colors. Bright red represents D′=1 and LOD⩾2; shades of pink/red, D′<1 and LOD⩾2; blue, D′=1 and LOD<2; white, D′<1 and LOD<2. The values in the boxes represent r2. A high correlation was observed between rs806378 and rs806380 (r2=0.76); and rs9450902 and rs10485170 (r2=0.84). (c) Summary of results for allelic  , genotypic

, genotypic  and haplotypic

and haplotypic  (three marker sliding window) analyses between the SNPs and antipsychotic-induced weight gain. The SNP rs806378 shows both allelic and genotypic association whereas rs9450902 and rs10485170 show only allelic association. The color reproduction of this figure is available on the html full text version of the manuscript.

(three marker sliding window) analyses between the SNPs and antipsychotic-induced weight gain. The SNP rs806378 shows both allelic and genotypic association whereas rs9450902 and rs10485170 show only allelic association. The color reproduction of this figure is available on the html full text version of the manuscript.

Data Analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0. The categorical variables were tested using a χ2-test and the continuous variables were tested using ANOVA, ANCOVA, or linear regression. Pearson's correlation was calculated between age, sex, duration of treatment, baseline Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). We decided a priori that the comparison of mean weight change (%) across genotypic categories would be the association-determining test. Only SNPs found to show a trend or significance were used for post hoc analyses. Haplotypes were constructed and percent change in weight was compared using QTPHASE routine in UNPHASED 2.0 (Dudbridge, 2003). Only haplotypes with frequencies greater than 5% were included in the analyses. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) and tagSNPs (r2=0.8, minor allele frequency >0.05) were determined using Haploview 4.1 (Barrett et al, 2005). LD blocks were constructed using solid spine of LD. Power calculations were carried out using Quanto 1.2.4 (Gauderman and Morrison, 2006). Assuming a minor allele frequency of 0.25 in a sample size of n=183, and a mean difference of 2.5% between carriers of the risk genotype, we had more than 80% power in a dominant and additive effect model. False discovery rate (FDR) q-values were calculated using the program QVALITY (http://noble.gs.washington.edu/proj/qvality; Käll et al, 2009). Similar to other publications, a q-value threshold 0.20 was used to indicate SNPs with most significant associations (van den Berg et al, 2009).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Biotin-labelled and unlabelled double-stranded oligonucleotides for each allele of rs806378 (T and C) and unlabelled oligonucleotides with the specific consensus-binding site for arylhydrocarbon receptor translocator (ARNT) and XBP1 (Clauss et al, 1996) were synthesized (Table 2, Eurofin MWG Operon, Huntsville, AL). Nuclear extract was prepared from SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells (ATCC: CRL2266) using the NE-PER Nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Pierce, IL). The complementary pairs of nucleotides suspended in STE Buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) were annealed using a thermocycler (Step 1: 95°C for 5 min, Step 2: 95°C (−1°C/cycle, 70 times), Step 3: HOLD at 4°C). The reannealed double-stranded oligonucleotides (20 fmol) were incubated with 2 μl of the nuclear extract, 1 × binding buffer, 2.5% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 ng/μl poly (dI dC), 0.05% NP-40 for 20 min at room temperature. For the competition experiments, unlabelled oligonucleotides at 200-fold molar excess (4 pmol) were preincubated with the nuclear extract before adding the biotin-labelled oligobucleotides. DNA protein complexes were fractioned on a 5% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5 × TBE for 35 min at 4°C. Complexes were electro-transferred to nylon membrane at 380 mA for 50 min, and cross-linked at 120 mJ/cm2 for 45 s. The biotinylated oligonucleotides were detected by chemiluminescence using the Chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module of the Light Shift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce, IL). The processed nylon membrane was exposed to an X-ray film for 2 min.

Table 2. Olignonucleotides for EMSA.

| Name | Oligonucleotides | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| rs806378-T | 5′-ACAGGCCTCATCACGTTGTATAATCAGGAG-3′ Rev-5′-CTCCTGATTATACAACGTGATGAGGCCTGT-3′ | This study |

| rs806378-C | 5′-ACAGGCCTCATCACGTCGTATAATCAGGAG-3′ Rev-5′-CTCCTGATTATACGACGTGATGAGGCCTGT-3′ | This study |

| XBP1 | 5′-GATCTCCTAGCAACAGATGCGTCATCTCAAA-3′ Rev-5′-TTTGAGATGACGCATCTGTTGCTAGGAGATC-3′ | Clauss et al (1996) |

| ARNT | 5′-GGGGATCGCGTGACAACCC-3′ Rev-5′-GGGTTGTCACGCGATCCCC-3′ | TRANSFAC |

Letters in bold indicate the position of the SNP rs806378.

RESULTS

Genetic Analysis

All the SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p>0.05, Table 3, Supplementary Table 1). Several clinical variables were different across the three sites, however, similar weight gain was observed across the clinical sites (Table 1). In the total sample set significant correlation was observed between weight change (%) and duration of treatment (p=0.045) but not with age (p=0.747) and baseline BPRS score (p=0.986). In the subgroup of patients of European ancestry on clozapine or olanzapine no significant correlation of duration of treatment (p=0.532), age (p=0.703), and baseline BPRS score (p=0.878) with weight change (%) was observed. Similarly, weight change (%) was not different between the male and female patients in the total (p=0.776) as well as the sub-group of patients of European ancestry on clozapine or olanzapine (p=0.822).

Table 3. List of SNPs Associated with Clozapine/Olanzapine (RiskMed) Induced Weight Gain at Genotypic and/or Allelic Level.

| SNP (location, bp) | Geno- type | Weight change (%)a All patients | p-value | Weight change (%)a All patients RiskMed | p-value | Weight change (%)a European Americans RiskMed | p-valueb | Allele | Count (freq) | Weight change (%) (variance) European Americans RiskMed | p-value | HWE p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs806378 (88916270) | CC | 5.20±7.29 (102) | 0.873 | 5.82±7.44 (78) | 0.763 | 2.69±5.45 (39) | 0.025 | C | 117 (0.69) | 3.84 (31.4) | 0.035 | 0.619 |

| CT | 5.20±7.30 (66) | 6.34±6.18 (46) | 6.14±5.68 (39) | T | 53 (0.31) | 5.83 (31.4) | ||||||

| TT | 4.36±4.59 (12) | 4.48±4.78 (8) | 4.95±4.96 (7) | |||||||||

| rs806380 (88921372) | GG | 4.69±4.06 (16) | 0.947 | 4.69±4.11 (11) | 0.871 | 5.04±4.15 (10) | 0.071 | G | 66 (0.39) | 5.35 (32.1) | 0.078 | 0.257 |

| GA | 4.93±5.94 (78) | 5.65±6.17 (55) | 5.49±5.89 (46) | A | 104 (0.61) | 3.77 (32.1) | ||||||

| AA | 5.19±7.52 (81) | 5.85±7.50 (63) | 2.41±5.63 (29) | |||||||||

| rs2180619 (88934671) | GG | 4.85±6.31 (39) | 0.876 | 5.72±6.97 (29) | 0.694 | 2.53±5.58 (12) | 0.295 | G | 68 (0.4) | 3.54 (31.9) | 0.097 | 0.651 |

| GA | 5.07±6.43 (86) | 5.17±6.89 (61) | 4.17±5.54 (43) | A | 102 (0.6) | 5.00 (31.9) | ||||||

| AA | 5.51±6.02 (49) | 6.36±6.24 (38) | 5.50±6.01 (30) | |||||||||

| rs9450902 (88936943) | GG | 7.58±9.69 (5) | 0.674 | 8.06±11.13 (4) | 0.753 | −3.41 (1) | 0.071 | G | 14 (0.08) | 1.21 (31.5) | 0.019 | 0.441 |

| GC | 4.96±6.60 (39) | 5.38±7.03 (30) | 2.15±3.93 (11) | C | 156 (0.92) | 4.75 (31.5) | ||||||

| CC | 4.93±6.41 (132) | 5.70±6.38 (96) | 4.92±5.86 (73) | |||||||||

| rs10485170 (88939371) | TT | 4.87±6.55 (139) | 0.362 | 5.50±6.55 (101) | 0.457 | 4.78±5.79 (76) | 0.087 | T | 162 (0.93) | 4.62 (31.2) | 0.034 | 0.334 |

| TC | 6.57±7.14 (37) | 7.37±7.89 (27) | 2.15±4.15 (10) | C | 12 (0.07) | 1.22 (31.2) | ||||||

| CC | 6.23±8.44 (4) | 6.23±8.44 (4) | −3.41 (1) |

Mean±SD (number of individuals).

SNPs with only one individual in a genotypic group were merged with the heterozygous genotypic group. All the p-values were calculated using ANOVA. rs806378: CC vs TT+TC, 2.69±5.46 vs 5.97±5.54, p=0.008; Bonferroni corrected p=0.153; FDR q-value=0.12; rs806380: AA vs GG+GA, 2.41±5.62 vs 5.41±5.59, p=0.022; Bonferroni corrected p=0.432, FDR q-value=0.165; HWE: Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, calculated for the patients with European ancestry on RiskMed (clozapine and olanzapine); values in bold indicate significance.

Association Study in the Total Sample

No association of any of the polymorphisms with weight change (%) was observed when we considered the total sample set of patients on various antipsychotics (p>0.05). Consistent with the literature (eg, reviewed by (Nasrallah, 2008)), we observed highest weight gain rates with clozapine (5.37%±6.27) and olanzapine (7.29%±8.17) in our sample compared with haloperidol (2.76%±4.29) and risperidone (3.54%±6.32). Clozapine and olanzapine have relatively similar receptor-binding profile (Nasrallah, 2008). Therefore, we assessed the subgroup of patients who received either clozapine or olanzapine for association with polymorphisms in CNR1 gene. No association of any of the SNPs with weight change was observed (p>0.05, Table 3, Supplementary Table 1).

Association Study in Patients of European Ancestry

The subjects of the study included patients of both European and African origin and the allele frequency of the SNPs analyzed in this study differed between these groups (data not shown). Therefore, a sub-analysis was carried out, stratified for ethnicity. Of the 20 tagSNPs, five SNPs showed a trend or significant association with antipsychotic-induced weight gain in the European subgroup (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1). To determine the contribution of these SNPs we performed backward linear regression. Duration of treatment was entered as an independent variable, and change in weight was the dependent variable. The polymorphism rs806378 emerged as the only significant SNP in genotypic comparison (B=2.14, β=0.234, p=0.035) as well as when the dominant effect of the minor allele T allele (B=3.33, β=0.286, p=0.010) was considered. In the genotypic model rs806378 explained 4.3% of the variance in the weight change, whereas it explained 7% in the dominant effect model. Carriers of the ‘T' allele (CT+TT) gained more weight (5.96% ±5.54) than the CC genotype carriers (2.76% ±5.51, p=0.008, FDR q-value 0.12). This translated into patients with the T allele gaining approximately 2.2 kg more than the patients homozygous for the CC genotype (CC vs CT+TT, 2.21±4.51 vs 4.33±3.89 kg; p=0.022). This was also reflected in the allelic analysis (C vs T allele, 3.84 vs 5.83%, p=0.035; Figure 1, Supplementary Table 2). In literature, age, sex, duration of treatment and severity of schizophrenia (baseline BPRS score) have been associated with the propensity of the patients to gain weight. Using ANCOVA, we corrected for the confounding effect of these variables, the association of rs806378 with weight change (%) was significant (CC vs CT+TT; p=0.017).

Haplotypes were constructed using a 3-marker sliding-window across the gene region. Although none of the haplotypes reached significance at the global level, haplotypes including rs806378 or rs9450902 and rs10485170 showed a trend for association (Figure 1). LD was calculated for the European sub-sample and several blocks of LD were observed similar to previous studies (Figure 1). A high correlation was observed between rs806378 and rs806380 (r2=0.76); and rs9450902 and rs10485170 (r2=0.84). Thus, based on the cumulative evidence from genotypic and allelic comparisons, rs806378 appears to be the SNP-driving association with antipsychotic-induced weight gain in this region.

Association Study in Patients of African Ancestry

The African-American patients showed a higher percent weight gain than patients with European ancestry when the total sample was considered (8.01±7.57 (n=55) vs 4.17±5.88 (n=117); p=0.004) or when only patients on the higher risk medication, that is, clozapine and olanzapine were considered (9.33±7.99 (n=41) vs 4.41±5.66 (n=88), p=0.01). In this small sample a significant association was observed only for the synonymous polymorphism rs1049353 (CC vs CT; 8.4±7.59 (n=36) vs 16.05±8.29 (n=5), p=0.043).

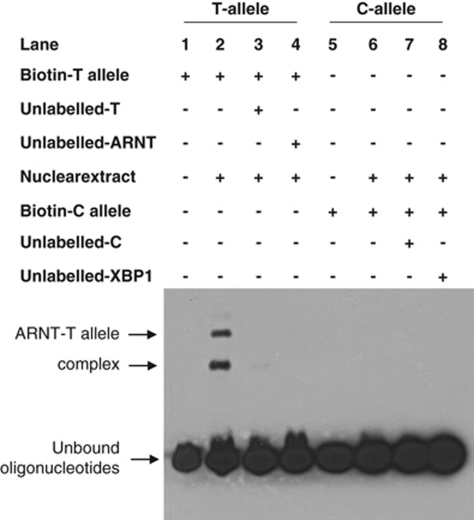

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

The SNP rs806378 is present in either exon 3 (5′untranslated region) of the alternate transcript (CB1-E) or is in intron 1 of the transcript (CB1-A, Figure 1). In other genes, regions within the 5′untranslated region and in introns have been reported to affect gene expression (Makkonen et al, 2009; Ott et al, 2009).

We carried out an in silico prediction (MatInspector, Genomatix) of transcription factor binding using a 30-bp oligonucleotide surrounding SNP rs806378. The presence of the ancestral C-allele was predicted to bind X-binding protein-1 (XBP-1, ttatacgACGTgatgag, the SNP is in bold and core binding site in capital letters), a member of the cAMP-response element-binding protein (Core similarity: 1.00, matrix similarity: 0.88). The T-allele was predicted to bind to arylhydrocarbon receptor translocator (ARNT, ttatacaaCGTGatgag), a member of the basic helix–loop–helix/Per–Arnt–Sim protein family (bHLH/PAS; core similarity: 1.00; matrix similarity: 0.897) but not to XBP-1.

An electrophoretic mobility shift assay was carried out and putative binding of ARNT to the T-allele was observed (Figure 2). Furthermore, in the competition assay, unlabelled oligonucleotide containing the consensus ARNT binding site was able to compete out the biotin-labeled T-allele carrying oligonucleotide, suggesting that the nuclear protein binding to this sequence is ARNT. The ancestral C-allele did not show binding to either ARNT or XBP-1 or any other nuclear protein.

Figure 2.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay for SNP rs806378. Identification of nuclear proteins binding to the T-allele (Lane 1–4) and C-allele (Lane 5–8). Our genetic studies suggested the T allele (TT+TC) was associated with antipsychotic-induced weight gain. Lane 2 shows binding of the transcription factor ARNT with the T allele.

DISCUSSION

The cannabinoid receptor 1 as part of the endocannabinoid system has emerged as an important receptor modulating diverse effects through its expression in multiple parts of the brain and peripheral tissues. CNR1 is considered to be important for modulating weight gain as evidenced by the effect of CNR1-antagonist rimonabant, which has been shown to foster weight loss both in animal studies as well as in clinical trials on humans. Genetic polymorphisms in the CNR1 gene have been associated with basal metabolic index, obesity and various metabolic parameters (Aberle et al, 2007; Baye et al, 2008; Benzinou et al, 2008; Gazzerro et al, 2007; Jaeger et al, 2008; Peeters et al, 2007; Russo et al, 2007), however some negative studies have also been reported (Aberle et al, 2007; Lieb et al, 2009; Muller et al, 2007). Significant association of polymorphisms in CNR1 with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa have also been reported (Monteleone et al, 2009; Siegfried et al, 2004), despite one negative report (Muller et al, 2008). Based on these many significant findings, we hypothesized that CNR1 might be associated with antipsychotic-induced weight gain.

In this study, we have tested the association of SNPs in the CNR1 gene with antipsychotic-induced weight gain in a group of well-characterized schizophrenia patients. The CNR1 gene was extensively covered with markers; however, of the 20 tagSNPs investigated, we did not observe any significant association in the total sample set. Reasons for this negative finding in the whole sample could be due to the inclusion of patients who received drugs, which have lesser propensity to cause weight gain (such as haloperidol and risperidone) and different ancestries. Similarly, the lack of association observed in the patients on higher risk medication for weight gain (clozapine and olanzapine) could be potentially due to inclusion of patients of different ancestries (European and African ancestry), which may have different susceptibility loci. We therefore stratified the samples according to their self-reported ethnicities and medication and observed significant association in patients of both African and European ancestry. In the patients with African ancestry, we observed a significant association with the synonymous polymorphism rs1049353 (C>T). However, the sample set is small and the observation became non-significant after correction for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni corrected p [0.043 × 20]=0.86).

We observed a significant effect of the polymorphism rs806378 (C>T) with the propensity to gain weight in the larger sample of patients of European ancestry who had received either clozapine or olanzapine. This polymorphism is present in the 5′UTR of the CB1-E transcript or intron2 of CB1-A (Figure 1). Our analyses indicate that carriers of the T-allele have a higher risk for weight gain. Although no functional effect has yet been described, the derived ‘T' allele of this polymorphism leads to generation of a transcription factor-binding site for ARNT, a member of the bHLH/PAS protein family. Using EMSA we provided evidence that ARNT is indeed the nuclear protein binding to this sequence and that the ancestral C-allele does not bind to either ARNT or any other nuclear protein. ARNT is known to heterodimerize with other bHLH-PAS proteins, primarily with single minded-1 (SIM1) and arylhydrocarbon receptor AHR. The AHR–ARNT heterodimer preferentially binds to TNGCGTG, the dioxin responsive element, whereas the SIM1–ARNT heterodimer binds to GT(G/A)CGTG (Yang et al, 2004). The latter appears to be more similar to the site containing the rs806378 polymorphism (CAACGTG). Interestingly SIM1 is essential for differentiation of neurons in the paraventricular nucleus, a region of hypothalamus critical for regulating physiological processes such as energy homeostasis and blood pressure. Furthermore, haploinsufficiency and disruption of SIM1 are associated with hyperphagic obesity in humans (Faivre et al, 2002; Holder et al, 2000). Similarly, mice with heterozygous deletion of Sim1 develop hyperphagia and obesity (Michaud et al, 2001). Thus the presence of this transcription factor-binding site may lead to a novel regulatory mechanism involving ARNT–SIM1-mediated transcriptional alteration.

The limitations of the significant findings in our stratified sub-samples include the relatively limited sample size, inclusion of self-reported ancestry, and lack of information on drug dose, cannabis use and diet. Our observation of different percent weight gain among CC vs CT+TT genotype (p=0.008) of rs806378 in patients of European ancestry on high risk medication did not withstand conservative corrections for multiple testing (Bonferroni corrected p=0.15, Table 3). However, the FDR q-value of 0.12 suggests that this observation is at least nominally significant. Furthermore, we had a strong biological rationale to test this gene for association with antipsychotic-induced weight gain (Benzinou et al, 2008; Hutchison et al, 2008; Weston-Green et al, 2008). The recent report of an association between the same T-allele of rs806378 with general obesity in a sample of French individuals further lends support to this observation (Benzinou et al, 2008). As mentioned earlier, SREBP expression is activated by CNR1 and recently Le Hellard et al (2009) reported a significant association of insulin-induced gene 2 (INSIG2) in a German sample. INSIG2 is expressed in the endoplasmic reticulum and sequesters SREBP by forming a trimeric complex along with SREBP cleavage-activating protein. This provides further evidence that genes involved in this pathway might have an important role in antipsychotic-induced weight gain.

In conclusion, the observations made in this study indicate a possible role of polymorphisms in CNR1 gene in antipsychotic-induced weight gain. However, to completely elucidate the role of CNR1these observations need to be further investigated and replicated in larger independent sample sets. In addition, it may be interesting to examine CNR1 for association with weight gain in other psychiatric disorders treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs.

Acknowledgments

Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) postdoctoral fellowship to AKT and RPS; CIHR operating grants to JLK and DJM (Genetics of Antipsychotic induced Metabolic Syndrome); NARSAD grants to DJM, MH41468, the Prentiss Foundation, Ritter Foundation, Hintz family, and the Peterson Family to HYM; The Bebensee Foundation fellowship to CCZ.

AKT/CCZ/OL/DS/RPS/PB/SZDJM/AL/IP: report no competing interests. HYM has received grants or is a consultant to: Abbott Labs, ACADIA, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Jansse, Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, Glaxo Smith Kline, Memory, Cephalon, Minster, Aryx, and BiolineRx. HYM is a shareholder of ACADIA. JAL reports having received research funding or consulting or educational fees from Allon, AstraZeneca, Bioline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest Labs, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Solvay and Wyeth. JLK has been a consultant to GSK, Sanofi-Aventis, Dainippon-Sumitomo.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Aberle J, Fedderwitz I, Klages N, George E, Beil FU. Genetic variation in two proteins of the endocannabinoid system and their influence on body mass index and metabolism under low fat diet. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39:395–397. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-977694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameri A, Wilhelm A, Simmet T. Effects of the endogeneous cannabinoid, anandamide, on neuronal activity in rat hippocampal slices. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1831–1839. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile VS, Masellis M, De Luca V, Meltzer HY, Kennedy JL. 759C/T genetic variation of 5HT(2C) receptor and clozapine-induced weight gain. Lancet. 2002;360:1790–1791. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baye TM, Zhang Y, Smith E, Hillard CJ, Gunnell J, Myklebust J, et al. Genetic variation in cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) is associated with derangements in lipid homeostasis, independent of body mass index. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1647–1656. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.11.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, Morales JO, Bellman P, Yangco B, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzinou M, Chevre JC, Ward KJ, Lecoeur C, Dina C, Lobbens S, et al. Endocannabinoid receptor 1 gene variations increase risk for obesity and modulate body mass index in European populations. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1916–1921. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss IM, Chu M, Zhao JL, Glimcher LH. The basic domain/leucine zipper protein hXBP-1 preferentially binds to and transactivates CRE-like sequences containing an ACGT core. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1855–1864. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.10.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Marsicano G, Tschop M, Grubler Y, Flachskamm C, Schubert M, et al. The endogenous cannabinoid system affects energy balance via central orexigenic drive and peripheral lipogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:423–431. doi: 10.1172/JCI17725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca V, Mueller DJ, de Bartolomeis A, Kennedy JL. Association of the HTR2C gene and antipsychotic induced weight gain: a meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10:697–704. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707007547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Goparaju SK, Wang L, Liu J, Batkai S, Jarai Z, et al. Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature. 2001;410:822–825. doi: 10.1038/35071088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudbridge F. Pedigree disequilibrium tests for multilocus haplotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;25:115–121. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingrod VL, Bishop JR, Moline J, Lin YC, Miller del D. Leptin and leptin receptor gene polymorphisms and increases in body mass index (BMI) from olanzapine treatment in persons with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre L, Cormier-Daire V, Lapierre JM, Colleaux L, Jacquemont S, Genevieve D, et al. Deletion of the SIM1 gene (6q16.2) in a patient with a Prader-Willi-like phenotype. J Med Genet. 2002;39:594–596. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.8.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamber KM, Macarthur H, Westfall TC. Cannabinoids augment the release of neuropeptide Y in the rat hypothalamus. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:646–652. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauderman WJ, Morrison JM.2006QUANTO 1.1: A computer program for power and sample size calculations for genetic-epidemiology studies . http://hydra.usc.edu/gxe .

- Gazzerro P, Caruso MG, Notarnicola M, Misciagna G, Guerra V, Laezza C, et al. Association between cannabinoid type-1 receptor polymorphism and body mass index in a southern Italian population. Int J Obes (London) 2007;31:908–912. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder JL, Jr, Butte NF, Zinn AR. Profound obesity associated with a balanced translocation that disrupts the SIM1 gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:101–108. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KE, Haughey H, Niculescu M, Schacht J, Kaiser A, Stitzel J, et al. The incentive salience of alcohol: translating the effects of genetic variant in CNR1. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:841–850. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger JP, Mattevi VS, Callegari-Jacques SM, Hutz MH. Cannabinoid type-1 receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with central obesity in a Southern Brazilian population. Dis Markers. 2008;25:67–74. doi: 10.1155/2008/841490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi N, Taylor DA. Anandamide administration into the ventromedial hypothalamus stimulates appetite in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:1151–1154. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käll L, Storey JD, Noble WS. QVALITY: non-parametric estimation of q-values and posterior error probabilities. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:964–966. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham TC, Williams CM, Fezza F, Di Marzo V. Endocannabinoid levels in rat limbic forebrain and hypothalamus in relation to fasting, feeding and satiation: stimulation of eating by 2-arachidonoyl glycerol. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:550–557. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kola B, Farkas I, Christ-Crain M, Wittmann G, Lolli F, Amin F, et al. The orexigenic effect of ghrelin is mediated through central activation of the endogenous cannabinoid system. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunos G.2007Understanding metabolic homeostasis and imbalance: what is the role of the endocannabinoid system Am J Med 120S18–S24.discussion S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri DK, Nurnberger JI., Jr A rapid non-enzymatic method for the preparation of HMW DNA from blood for RFLP studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5444. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hellard S, Theisen FM, Haberhausen M, Raeder MB, Ferno J, Gebhardt S, et al. Association between the insulin-induced gene 2 (INSIG2) and weight gain in a German sample of antipsychotic-treated schizophrenic patients: perturbation of SREBP-controlled lipogenesis in drug-related metabolic adverse effects. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:308–317. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb W, Manning AK, Florez JC, Dupuis J, Cupples LA, McAteer JB, et al. Variants in the CNR1 and the FAAH genes and adiposity traits in the community. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:755–760. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makkonen H, Kauhanen M, Paakinaho V, Jaaskelainen T, Palvimo JJ. Long-range activation of FKBP51 transcription by the androgen receptor via distal intronic enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4135–4148. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masellis M, Basile V, Meltzer HY, Lieberman JA, Sevy S, Macciardi FM, et al. Serotonin subtype 2 receptor genes and clinical response to clozapine in schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19:123–132. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias I, Di Marzo V. Endocannabinoids and the control of energy balance. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007;18:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud JL, Boucher F, Melnyk A, Gauthier F, Goshu E, Levy E, et al. Sim1 haploinsufficiency causes hyperphagia, obesity and reduction of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1465–1473. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone P, Bifulco M, Di Filippo C, Gazzerro P, Canestrelli B, Monteleone F, et al. Association of CNR1 and FAAH endocannabinoid gene polymorphisms with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: evidence for synergistic effects. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:728–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller DJ, De Luca V, Sicard T, King N, Hwang R, Volavka J, et al. Suggestive association between the C825T polymorphism of the G-protein beta3 subunit gene (GNB3) and clinical improvement with antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005a;15:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller DJ, Kennedy JL. Genetics of antipsychotic treatment emergent weight gain in schizophrenia. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7:863–887. doi: 10.2217/14622416.7.6.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller DJ, Klempan TA, De Luca V, Sicard T, Volavka J, Czobor P, et al. The SNAP-25 gene may be associated with clinical response and weight gain in antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2005b;379:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller TD, Reichwald K, Bronner G, Kirschner J, Nguyen TT, Scherag A, et al. Lack of association of genetic variants in genes of the endocannabinoid system with anorexia nervosa. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2:33. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller TD, Reichwald K, Wermter AK, Bronner G, Nguyen TT, Friedel S, et al. No evidence for an involvement of variants in the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) in obesity in German children and adolescents. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;90:429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah HA. Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: insights from receptor-binding profiles. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:27–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K, Walsh D, Deeter P, Sheehan F. A phase II study of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol for appetite stimulation in cancer-associated anorexia. J Palliat Care. 1994;10:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Hyiaman D, DePetrillo M, Pacher P, Liu J, Radaeva S, Batkai S, et al. Endocannabinoid activation at hepatic CB1 receptors stimulates fatty acid synthesis and contributes to diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1298–1305. doi: 10.1172/JCI23057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott CJ, Suszko M, Blackledge NP, Wright JE, Crawford GE, Harris A. A complex intronic enhancer regulates expression of the CFTR gene by direct interaction with the promoter. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:680–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters A, Beckers S, Mertens I, Van Hul W, Van Gaal L. The G1422A variant of the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) is associated with abdominal adiposity in obese men. Endocrine. 2007;31:138–141. doi: 10.1007/s12020-007-0022-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravinet Trillou C, Arnone M, Delgorge C, Gonalons N, Keane P, Maffrand JP, et al. Anti-obesity effect of SR141716, a CB1 receptor antagonist, in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00545.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravinet Trillou C, Delgorge C, Menet C, Arnone M, Soubrie P. CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout in mice leads to leanness, resistance to diet-induced obesity and enhanced leptin sensitivity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:640–648. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo P, Strazzullo P, Cappuccio FP, Tregouet DA, Lauria F, Loguercio M, et al. Genetic variations at the endocannabinoid type 1 receptor gene (CNR1) are associated with obesity phenotypes in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2382–2386. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarzani R, Bordicchia M, Marcucci P, Bedetta S, Santini S, Giovagnoli A, et al. Altered pattern of cannabinoid type 1 receptor expression in adipose tissue of dysmetabolic and overweight patients. Metabolism. 2009;58:361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried Z, Kanyas K, Latzer Y, Karni O, Bloch M, Lerer B, et al. Association study of cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) alleles and anorexia nervosa: differences between restricting and binging/purging subtypes. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;125B:126–130. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templeman LA, Reynolds GP, Arranz B, San L. Polymorphisms of the 5-HT2C receptor and leptin genes are associated with antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain in Caucasian subjects with a first-episode psychosis. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:195–200. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg SW, Dollé ME, Imholz S, van der A DL, van ‘t Slot R, Wijmenga C, et al. Genetic variations in regulatory pathways of fatty acid and glucose metabolism are associated with obesity phenotypes: a population-based cohort study. Int J Obes (London) 2009;33:1143–1152. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:255–262. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston-Green K, Huang XF, Han M, Deng C. The effects of antipsychotics on the density of cannabinoid receptors in the dorsal vagal complex of rats: implications for olanzapine-induced weight gain. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:827–835. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708008560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SC. Role of the endocannabinoid system in regulating cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors. Am J Med. 2007;120:S19–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Boucher F, Tremblay A, Michaud JL. Regulatory interaction between arylhydrocarbon receptor and SIM1, two basic helix-loop-helix PAS proteins involved in the control of food intake. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9306–9312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang PW, Ishiguro H, Ohtsuki T, Hess J, Carillo F, Walther D, et al. Human cannabinoid receptor 1: 5′ exons, candidate regulatory regions, polymorphisms, haplotypes and association with polysubstance abuse. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:916–931. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZJ, Yao ZJ, Mou XD, Chen JF, Zhu RX, Liu W, et al. [Association of −2548G/A functional polymorphism in the promoter region of leptin gene with antipsychotic agent-induced weight gain] Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2003;83:2119–2123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.