Abstract

After the intracisternal administration of 6-hydroxydopamine, brain levels of norepinephrine were reduced significantly with or without pargyline pretreatment. Depletion of dopamine in the central nervous system was found to be enhanced markedly by pargyline administration at higher dose levels of 6-hydroxydopamine. Brain serotonin concentrations were not altered. The effects of 6-hydroxydopamine were long-lasting with the depletion of brain amines persisting at 78 days. After norepinephrine-H3 intracisternally to animals treated with 6-hydroxydopamine, labeled norepinephrine uptake was diminished with a corresponding reduction of deaminated catechols and a marked increased in methylated amines. Tyrosine hydroxylase activity was found to be reduced in brainstem, caudate nucleus and whole brain in 6-hydroxydopamine-treated animals. Conversion of tyrosine-H3 to labeled norepinephrine and dopamine was also markedly diminished. The results support the view that 6-hydroxydopamine produces a “central sympathectomy” when introduced into cerebrospinal fluid.

During the past few years, understanding of the role and mechanisms of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system has been advanced by the development of techniques of sympathectomy and through the use of an array of pharmacologic agents. Nevertheless, central noradrenergic mechanisms have been more difficult to assess. The diffuse nature of the noradrenergic system (Carlsson et al., 1962) has made discrete lesioning of norepinephrine cells in brain virtually impossible. Furthermore, pharmacologic agents used to study central mechanisms have had the disadvantage of altering not only the catecholamine systems in the central nervous system but also in the periphery. A pharmacologic agent which could be introduced directly into the central nervous system and which would destroy the central noradrenergic system without altering the peripheral system would offer obvious advantages. Recent observations suggest that 6-hydroxydopamine may prove to be such an agent (Tranzer and Thoenen, 1968; Uretsky and Iversen, 1969).

The observation by Porter et al. (1963) and Laverty et al. (1965) that 6-hydroxydopamine induced a long-lasting depletion of norepinephrine in peripheral organs with sympathetic innervation led to the hypothesis that 6-hydroxydopamine destroyed norepinephrine binding sites (Porter et al., 1963). Recently, Tranzer and Thoenen (1968) have confirmed and extended these observations showing that two weeks after treatment with 6-hydroxydopamine virtually all adrenergic fibers were absent from sympathetically innervated tissues. These reports of peripheral chemical sympathectomy by 6-hydroxydopamine (Thoenen and Tranzer, 1968; Tranzer and Thoenen, 1968) led to investigation of the possibility that 6-hydroxydopamine might also produce selective destruction of brain catecholamine neurons when introduced into the central nervous system (Uretsky and Iversen, 1969; Bloom et al., 1969; Anagnoste et al., 1969; Traylor and Breese, 1970). Ungerstedt (1968) reported that 6-hydroxydopamine produced degeneration of central catecholamine neurons when injected into a localized area of brain. Utilizing electron micrographic examination of areas rich in adrenergic neurons, Bloom and associates (1969) demonstrated that 6-hydroxydopamine administered into cerebrospinal fluid caused degeneration of central noradrenergic fibers.

The present experiments were designed to investigate the depletion of brain catecholamines after intracisternally administered 6-hydroxydopamine, to determine the effect of this procedure on the retention and metabolism of intracisternally administered H3-norepinephrine and to measure the effect of this derivative on brain tyrosine hydroxylase. Experiments were performed on animals with or without pargyline pretreatment. Our data further support the view that 6-hydroxydopamine can produce selective degeneration of central catecholamine-containing neurons.

Methods

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (140–180 g) were given from 25 to 200 μg of 6-hydroxydopamine hydrobromide intracisternally as described previously (Schanberg et al., 1968). The compound was dissolved in Elliott’s “B” solution (Baxter Laboratories, Inc., Morton Grove, 111.) containing 1 mg/ml of ascorbic acid to prevent oxidation of the 6-hydroxydopamine; total volume administered was 25 μl. In an attempt to decrease deamination of 6-hydroxydopamine (Breese et al., 1969), some animals received 50 mg/kg of pargyline i.p. 30 minutes before the 6-hydroxydopamine injection. A second dose of 6-hydroxydopamine (200 μg) was administered to a few animals seven days after the first injection; pargyline was administered with the first but not with the second dose. After the surgical procedure, each animal received 0.05 ml of benzathine penicillin G suspension i.m.

For the measurement of brain concentrations of norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin, animals were killed by cervical fracture and decapitated at various times after injection. Brains were removed, rinsed in cold water, homogenized in 10 ml of ice-cold 0.4 N perchloric acid, frozen and analyzed within 24 hours. After thawing and centrifugation of the homogenate, an aliquot of the clear supernatant was adjusted to pH 8.6 with sodium hydroxide, and the catecholamines were adsorbed onto alumina (Woelm, neutral) by the method of Anton and Sayre (1962). After stirring, the alumina was transferred to a chromatographic column and washed with 10 ml of 0.4 N sodium acetate solution (pH 8.6) and with 20 ml of glass-distilled water. The catecholamines were eluted from the alumina wtih 7 ml of 0.2 N acetic acid. Endogenous norepinephrine in the acetic acid eluate was assayed according to the method of Häggendal (1963) except that mercaptoethanol was substituted for British anti-lewisite. Dopamine was assayed according to the method of Anton and Sayre (1964). Values for endogenous amines were uncorrected for recovery which averaged 89% for norepinephrine and 84% for dopamine. Brain serotonin was isolated from an aliquot of the supernatant by the method of Bogdanski et al. (1956) and measured by the fluorescent method of Snyder et al. (1965).

Some animals were given norepinephrine-H3 (5 μc, 7.1 c/mmol) intracisternally in a volume of 25 μl. After the procedure outlined above for killing and homogenization, labeled norepinephrine and its metabolites were isolated with the method of Schanberg et al. (1967). When tyrosine-H3 (34.7 c/mmol) was injected either intracisternally (15 μc) or i.v. (40 μc), the animals were sacrificed one hour later; radioactive norepinephrine and dopamine formed from tyrosine-H3 were isolated according to the method of Sedvall et al. (1968). Less than 0.5% dopamine was noted in the norepinephrine fraction and vice versa. Radioactive amine values were uncorrected for recovery which was 80% for norepinephrine and 70% for dopamine. All radioactivity was measured by scintillation spectrometry; an internal standard of toluene-H3 was used to correct for counting efficiency.

Dissection of brain parts was performed on a moistened filter paper placed on a chilled glass plate. The term “brainstem” as used in this manuscript refers to the area of brain caudal to a cut made behind the superior colliculi after removal of the cerebellar cortices. The term “caudate” refers to that area of brain which lies adjacent to the lateral ventricle and is bounded by the radiation of the corpus callosum. Access to the caudate mass, which contained portions of the globus pallidus, was obtained through the lateral ventricle after hemisection of the whole brain. After removal of the caudate, the remainder of the brain tissue was assayed and is referred to as “rest of brain.”

Tyrosine hydroxylase was isolated from whole brain and brain parts according to the method of Musacchio et al. (1969) except that the enzyme was precipitated from a 1:1 mixture of sample and ammonium sulfate solution. Enzyme activity was determined by measuring the formation of tritiated water from 3,5-ditritiotyrosine in a modified procedure of Nagatsu et al. (1964). The incubation mixture for whole brain, rest of brain and brainstem consisted of tyrosine (100 mμmol), 2.9 × 106 cpm of ditritiotyrosine, 0.5 μmol of 2-amino-4-hydroxy-6,7 dimethyltetrahydropteridine in 0.1 ml of 1 M mercaptoethanol and 05 ml of enzyme preparation. For measurement of activity in caudate, half quantities of each reactant were used with the final volume measuring 0.5 ml. Incubation was at 37°C for 30 minutes. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.25 ml of 6% trichloroacetic acid. The mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant placed on a column of Dowex-50 (NH4+) (3 by 0.8 cm). The effluent and one wash were combined and mixed with 10 ml of phosphor-Triton (1:1) and counted. Monoamine oxidase activity was measured according to the method of Wurtman and Axelrod (1964).

The 6-hydroxydopamine HBr was purchased from Regis Chemical Company (Chicago, Ill.) and used without further purification. Pargyline was kindly supplied by Abbott Laboratories (North Chicago, Ill.) H3-tyrosine (34.7 c/mmol), H3-norepinephrine (7.1 c/mmol) and C14-tryptamine (5 mc/mmol) were purchased from New England Nuclear Corporation (Boston, Mass.). All doses of the compounds used in this study are expressed as their free base.

Results

Effect of 6-hydroxydopamine on brain norepinephrine, dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine

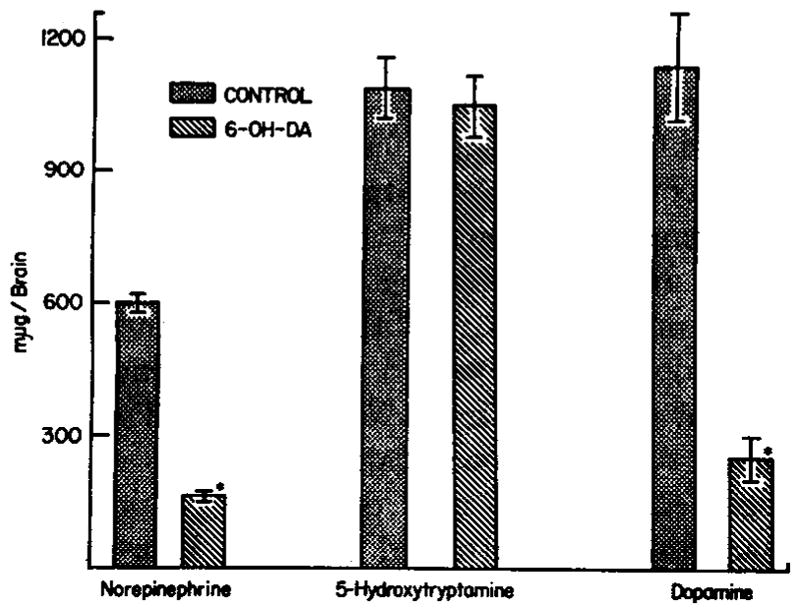

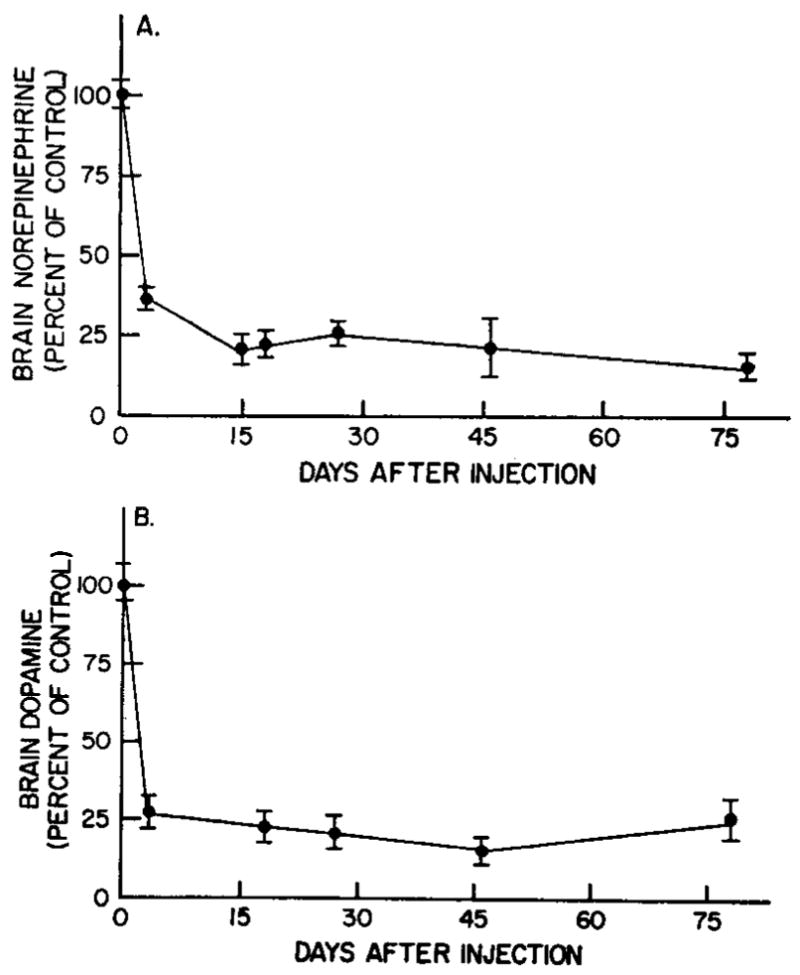

After the intracisternal injection of 200 μg of 6-hydroxydopamine in animals pretreated with pargyline, brain norepinephrine and dopamine were reduced without effecting brain serotonin (fig. 1). The depleting effect on brain norepinephrine and dopamine of a single 200 μg injection of 6-hydroxydopamine after monoamine oxidase inhibition was noted as early as 3 days and persisted for as long as 78 days (fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Effect of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OH-DA) on brain norepinephrine, 5-hydroxytryptamine and dopamine. Animals pretreated with pargyline received 200 μg of 6-hydroxydopamine intracisternally and were killed 21 days later. Each bar is the mean of 8 to 16 animals. Vertical bars indicate S.E.M. *, P < .001.

Fig. 2.

Effect of 6-hydroxydopamine on brain norepinephrine (A) and dopamine (B) at various times after injection. Animals pretreated with pargyline received 200 μg of 6-hydroxydopamine and were killed at various times after this injection. Control values for norepinephrine and dopamine were 605 ± 12.2 and 1136 ± 58 mμg, respectively. Vertical bars indicate S.E.M. Each value represents six to eight determinations.

Effect of pargyline pretreatment on the reduction of brain catecholcmines by 6-hydroxydopamine

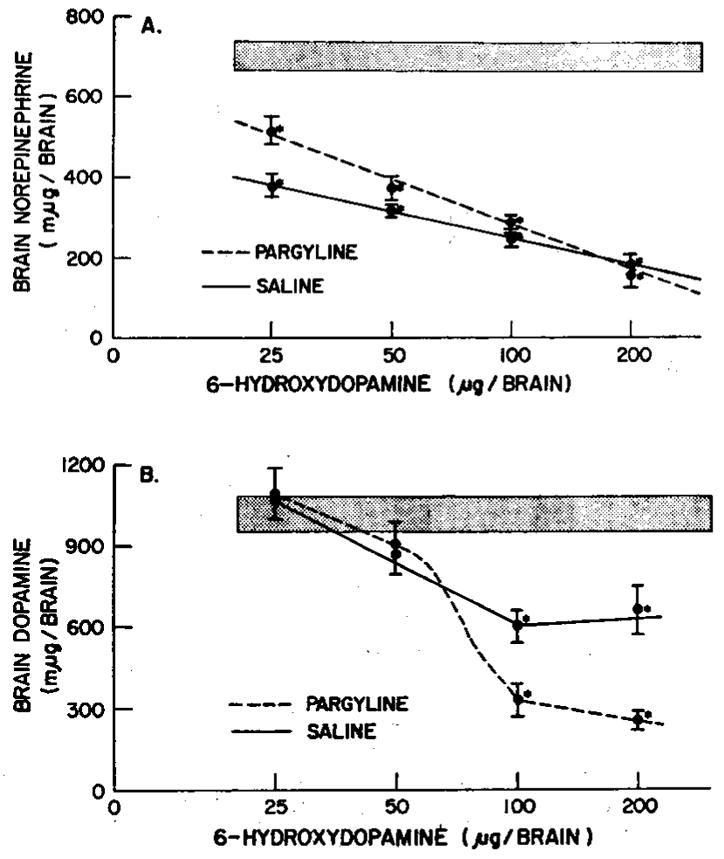

The administration of 6-hydroxydopamine intracisternally was found to lower whole brain norepinephrine significantly at all doses administered irrespective of the presence or absence of pargyline pretreatment (fig. 3). However, at the lowest dose of 6-hydroxydopamine the administration of pargyline was found to inhibit significantly (P < .01) the depleting effect of 6-hydroxydopamine upon brain norepinephrine. The effect of 200 μg of 6-hydroxydopamine in pargyline-treated animals was not significantly different from that in 6-hydroxydopamine-treated animals which did not receive pargyline. Thus, pargyline pretreatment does not appear to offer any advantage in the 6-hydroxydopamine-induced depletion of brain norepinephrine. With or without pargyline, heart norepinephrine was not affected by intracisternally administered 6-hydroxydopamine.

Fig. 3.

Effect of pargyline on brain depletion of catecholamines (A and B) by 6-hydroxydopamine. Various doses of 6-hydroxydopamine were administered intracisternally to animals with or without pargyline pretreatment. Animals, were sacrificed 16 or 21 days later. Stippled area indicates control values ±S.E.M. of 20 animals. Each point indicates the mean of 6 to 12 animals; vertical bar indicates the S.E.M. *, P < .01.

In contrast to the pargyline effect on norepinephrine depletion by 6-hydroxydopamine, a quite different depleting pattern was noted on dopamine (fig. 3). Without pargyline, 6-hydroxydopamine caused a dose-dependent reduction of dopamine from 25 to 100 μg. The lower doses of 6-hydroxydopamine did not cause a significant depletion of dopamine in either the pargyline or nontreated animals. However, 6-hydroxydopamine administered at the 100 μg and 200 μg doses to pargyline-treated animals had marked effects on brain dopamine, depleting the amine 66 and 76%, respectively. Animals which did not receive pargyline before intracisternally administered 6-hydroxydopamine had their brain dopamine reduced approximately 40%.

Metabolism of intracisternally administered H3-norepinephrine in 6-hydroxydopamine-treated rats

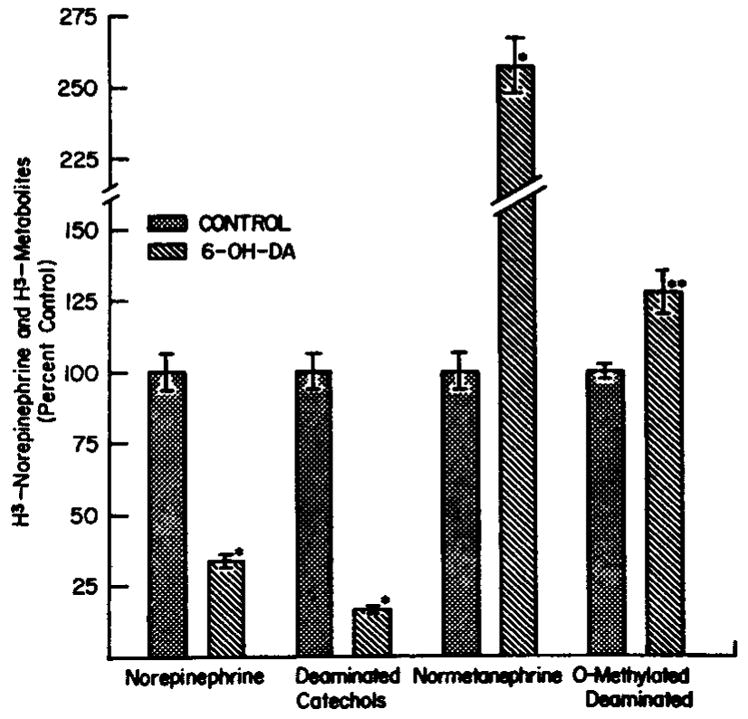

Two hours after the intracisternal administration of H3-norepinephrine, labeled norepinephrine in brain tissue was found to be reduced by 76% (fig. 4). At the same time, H3-normetanephrine was increased 264% and deaminated catechols were reduced by 83%. The O-methylated deaminated products of labeled norepinephrine were only slightly elevated in 6-hydroxydopamine-treated animals.

Fig. 4.

Effect of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-0H-DA) on the metabolism of intracisternally administered norepinephrine-H3. Two doses of 6-hydroxydopamine (200 μg) were administered: the first was injected to pargyline-treated animals 21 days before sacrifice and the second dose was administered 7 days after the first dose. Animals were sacrificed 2 hours after the intracisternal injection of H3-norepinephrine (5 μc). Results are expressed as percentage of control ±S.E.M. Each value represents the mean of at least 10 determinations. Control mean norepinephrine-H3 = 1000 mμc/brain; normetanephrine-H3 = 136 mμc/brain; H3-deaminated catechols = 3 μc/brain; labeled O-methylated deaminated metabolites = 700 mμc/brain. *, P < .001; **, P < .05.

Formation of labeled norepinephrine and dopamine from H3-tyrosine

After the administration of radioactive tyrosine, labeled dopamine and norepinephrine are formed (Sedvall et al., 1968). Whether the label tyrosine was administered i.v. or intracisternally, animals treated with 6-hydroxydopamine were found to have reduced amounts of labeled dopamine as well as norepinephrine when compared to controls (table 1). In an attempt to determine if 6-hydroxydopamine might be interfering with the storage of amines but not synthesis, animals given H3-tyrosine i.v. were pretreated with pargyline in an attempt to spare catecholamines which might be synthesized. Nevertheless, results by the two routes of administration were comparable. After i.v. injection of H3-tyrosine, tritium-labeled norepinephrine formed was reduced 82% while H3-dopamine formed was reduced 75%. The amount of radioactive tyrosine found in brain was not significantly different from its corresponding control.

TABLE 1.

Effect of 6-hydroxydopamine on the synthesis of H3-catecholamines from H3-tyrosinea

| Tyrosine Administration | Treatment | H3-Tyrosine | H3-Norepinephrine | H3-Dopamine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenousb | Saline | 243,000 ± 13,000 | 710 ± 70 | 565 ± 40 |

| 6-Hydroxydopamine | 266,000 ± 16,000 | 130 ± 25c | 140 ± 25c | |

| Intracisternal | Saline | 168,000 ± 9,500 | 940 ± 100 | 555 ± 51 |

| 6-Hydroxydopamine | 174,000 ± 17,000 | 218 ± 34c | 192 ± 13c | |

Results expressed as counts per minute per brain and are the mean ± S.E.M. of 6 to 12 determinations. Rats received 40 μc of H3-tyrosine i.v. or 15 μc intracisternally 21 days after the intracisternal injection of 6-hydroxydopamine (200 μg, 2 doses). Animals were sacrificed 1 hour after the labeled tyrosine.

Animals received pargyline (50 mg/kg) 30 minutes before the administration of H3-tyrosine.

P < .001.

Effect of 6-hydroxydopamine on brain tyrosine hydroxylase and monoamine oxidase activity

In animals treated with 6-hydroxydopamine in combination with pargyline, whole brain tyrosine hydroxylase activity in vitro was found to be decreased by approximately 80% (table 2). This was in close agreement with the depletion of whole brain catecholamines (fig. 1; table 2). A comparable loss of tyrosine hydroxylase activity and norepinephrine depletion was also observed in brainstem. Tyrosine hydroxylase activity in the caudate, normally an active region (McGeer et al., 1967), was markedly reduced in 6-hydroxydopamine-treated rats. Dopamine concentration in the caudate of animals similarly treated was reduced by some 81% (table 2). Tyrosine hydroxylase activity in brain portions remaining after removal of the caudate was approximately 20% of control with catecholamine content being altered proportionally. Brain monoamine oxidase showed no decrease in whole brain or in brain parts examined (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effect of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OH-DA) on brain catecholamines and tyrosine hydrosylase activity

| Brain Part b | Norepinephrine |

Dopamine |

Tyrosine Hydroxylase |

Monoamine Oxidase |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 6-OH-DA | Control | 6-OH-DA | Control | 6-OH-DA | Control | 6-OH-DA | |

| mμg/g | mμg/g | μμmol/mg/hr | mμmol/mg/hr | |||||

| Whole Brain | 330 ± 9.5 (25) | 74 ± 4c (25) | 304 ± 13 (25) | 55 ± 4c (25) | 4.32 ± 0.26 (8) | 0.96 ± 0.16c (8) | 1.11 ± 0.10 (8) | 1.09 ± 0.10 (8) |

| Brainstem | 450 ± 18 (3) | 91 ± 6c (3) | 6.26 ± 0.55 (8) | 1.30 ± 0.46c (8) | 1.46 ± 0.12 (8) | 1.41 ± 0.15 (8) | ||

| Caudate | 174 ± 20 (4) | 46 ± 15c (4) | 5880 ± 203 (9) | 1093 ± 33c (8) | 20.7 ± 2.10 (14) | 2.53 ± 0.20c (10) | 1.40 ± 0.15 (8) | 1.41 ± 0.14 (8) |

| Rest of brain | 319 ± 18 (5) | 79 ± 10c (5) | 296 ± 23 (5) | 140 ± 12c (5) | 4.33 ± 0.24 (8) | 0.88 ± 0.18c (6) | 1.14 ± 0.11 (8) | 1.12 ± 0.10 (8) |

Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M.; numbers in parentheses indicate the number of animals per group. Brain dissections described in Methods.

Animals in which whole brain and brainstem were assayed were given 2 doses of 6-hydroxydopamine (200μg) as described in Method. Animals in which the caudate and rest of brain were assayed received 200 μg of 6-hydroxydopamine with pargyline. All animals were sacrificed 14 days after the initial treatment.

P < .001.

Discussion

The reports (Tranzer and Thoenen, 1968; Malmfors and Sachs, 1968) that 6-hydroxydopamine caused a chemical sympathectomy peripherally prompted several laboratories to investigate whether this compound would display the same neurotoxicity toward central catecholamine neurons (Uretsky and Iversen, 1969; Groppetti et al., 1969; Traylor and Breese, 1970). Uretsky and Iversen (1969) have found brain norepinephrine to be lowered for as long as 32 days, thus lending strong support to the view that noradrenergic degeneration could be induced by 6-hydroxydopamine. The present study shows that depletion of brain catecholamines persists at 78 days. With the use of electron microscopy, Bloom and co-workers (1969) have confirmed the presence of degenerating norepinephrine neurons within the central nervous system after administering 6-hydroxydopamine intracisternally. Several reports have indicated that sympathetic denervation decreases tyrosine hydroxylase activity in peripheral organs with adrenergic innervation (Sedvall et al., 1967; Mueller et al., 1969). Therefore, the marked reduction of tyrosine hydroxylase activity in brain (table 2) and the decreased noreinephrine synthesis from tyrosine (table 1) after 6-hydroxydopamine treatment not only add support to the view that noradrenergic neuronal degeneration occurs but also suggests that destruction is quite widespread.

Bloom and associates (1969) recently reported that norepinephrine neurons were more sensitive to depletion by 6-hydroxydopamine than dopaminergic nerve cells. The results of this present study are in full agreement with these earlier results (fig. 3). This observation might have been expected because of the report that dopaminergic neurons are resistant to depletion by intracisternally administered amphetamine derivatives which lower brain norepinephrine levels significantly (Breese et al., 1970). Preliminary evidence indicates that a multiple injection sequence of lower doses of 6-hydroxydopamine may deplete norepinephrine to an even greater extent than a single injection with minimal influence on brain dopamine levels (unpublished data).

The study of the effects of 6-hydroxydopamine peripherally indicated that selective degeneration of adrenergic nerves occurred only in the distal part of the neuron, but not in the perikaryon (Tranzer and Thoenen, 1968). In brain, Bloom and associates (1969) found depletion of norepinephrine by 6-hydroxydopamine to be greatest in areas containing axons and nerve terminals and least in those areas which contained biogenic amine cell bodies. Whereas electron microscopic evaluation of fiber endings would strongly suggest that 6-hydroxydopamine eliminates norepinephrine-containing terminals, the morphologic evidence concerning the fate of the cell bodies is not yet available (Bloom et al., 1969). In the present study, all brain areas seem to be influenced uniformly by the neuronal toxicity of 6-hydroxydopamine. Whether this increased effect may be due to adrenergic cell body destruction or to an increased effectiveness on fiber terminals was not established. Whatever may be the case, it is clear that the effects are quite prolonged (fig. 2), suggesting that axonal regeneration does not occur within the central nervous system as previously reported for the periphery (Thoenen and Tranzer, 1968).

After the monoamine oxidase inhibitor pargyline, 6-hydroxydopamine (200 μg) was found to decrease not only brain norepinephrine but also dopamine (fig. 1). Early observations in our laboratory had indicated that brain dopamine was only moderately altered by 6-hydroxydopamine. With this in mind, it was reasoned that taking advantage of the fact that amines pass slowly from the central nervous system after monoamine oxidase inhibition (Schanberg, et al., 1968; Breese et al., 1969) this minor effect of 6-hydroxydopamine could be amplified. As shown in figure 1, this procedure. has permitted consistent depletion of brain dopamine as well as norepinephrine (Breese et al., 1970). Furthermore, the results of the present study and the recent work of Uretsky and Iversen (1970) emphasize that dopaminergic neurons are not only depleted but are probably affected by the neurotoxicity of 6-hydroxydopamine. This is exemplified by the prolonged depletion of dopamine (fig. 2), by lack of in vivo synthesis of labeled dopamine from H3-tyrosine (table 1) and by the reduction of tyrosine hydroxylase activity in the basal ganglia, (table 2) well known for its high dopamine content (Carlsson, 1959). In further support of this view, F. E. Bloom (personal communication) has recently found degenerating fibers in the caudate of pargyline-treated animals which have received 6-hydroxydopamine intracisternally.

After the administration of H3-norepinephrine the amount of labeled normetanephrine isolated from brains of 6-hydiroxydopamine-treated animals was increased considerably over levels in control brains. This suggests that the enzyme catechol-O-methyltransferase is not altered by 6-hydroxydopamine treatment. The reduction of deaminated catechols and the increased amounts of normetanephrine observed after 6-hydroxydopamine treatment is similar to but greater than that reported to occur after desipramine (Schanberg et al., 1967; Schildkraut et al., 1967). These results are probably linked to the decreased neuronal uptake observed to occur after both desipramine and 6-hydroxydopamine (Schanberg et al., 1967, fig. 2).

Selective elimination of central norepinephrine or norepinephrine and dopamine neurons should aid significantly in the effort to define the central role of these amines. However, the usefulness of 6-hydroxydopamine as a pharmacologic agent for evaluating the central role of catecholamines has yet to be established. In view of the central function attributed to these amines, it has been somewhat surprising to find that the general appearance of rats “centrally sympathectomized” with 6-hydroxydopamine has thus far been grossly indistinguishable from that of untreated controls except for a slight decrease in body weight and a lack of self-grooming. Certainly these animals do not display a classical “reserpine syndrome” (Bein, 1953). Experiments are presently underway to evaluate further the role of 6-hydroxydopamine as a specific tool for the study of central adrenergic mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The excellent technical assistance of Miss Carol Talbott, Miss Marcine Kinkead and Mr. Ronald Moore are gratefully acknowledged. We also express our gratitude to Dr. Jose M. Musacchio for furnishing our laboratory with the method to measure tyrosine hydroxylase.

Footnotes

This project was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grants MH 16522-01 and HD-03110-01.

References

- Anagnoste B, Backstbom T, Goldstein M. The effect of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OH-DA) on catecholamine biosynthesis in the brain of rats. Pharmacologist. 1969;11:274. [Google Scholar]

- Anton AH, Satre DF. A study of the factors affecting the aluminum oxide-trihydroxyindole procedure for the analysis of catecholamines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1962;138:360–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton AH, Saybe DF. The distribution of dopamine and dopa in various animals and a method for their determination in diverse biological material. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1964;145:326–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bein HJ. Zur Pharmakologie des Reserpin, eines neuen Alkaloids aus Rauwolfia serpentina Benth. Experientia (Basel) 1953;9:107–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02178342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom FE, Algebi S, Geoppetti A, Revuetta A, Costa E. Lesions of central norepinephrine terminals with 6-OH-dopamine: Biochemistry and fine structure. Science (Washington) 1969;166:1284–1286. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3910.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanski DF, Pletscher A, Brodie BB, Udenfriend S. Identification and assay of serotonin in brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1956;117:82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Chase TN, Kopin IJ. Metabolism of tyramine-H3 and octopamine-H3 by rat brain. Biochem Pharmacol. 1969;18:863–869. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(69)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Kopin IJ, Weise VK. Effects of amphetamine derivatives on brain dopamine and norepinephrine. Brit J Pharmacol. 1970;38:537–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1970.tb10595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A. The occurrence, distribution, and physiological role of catecholamines in the nervous system. Pharmacol Rev. 1959;11:490–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A, Falck B, Hillarp NA. Cellular localization of brain monoamines. Acta Physiol Scand. 1962;56(suppl):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groppetti A, Algeri F, Bloom F, Costa E, Revuelta A. Central effects of intracisternal injections of 6-hydroxydopamine (6HDM) Pharmacologist. 1969;11:275. [Google Scholar]

- Häggendal J. An improved method for fluorometric determination of small amounts of adrenaline and noradrenaline in plasma and tissues. Acta Physiol Scand. 1963;59:242–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1963.tb02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverty R, Shabman DF, Vogt M. Action of 2,4,5-trihydroxyphenylethylamine on the storage and release of noradrenaline. Brit J Pharmacol. 1965;24:549–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1965.tb01745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmfors T, Sachs C. Degeneration of adrenergic nerves produced by 6-hydroxydopamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1968;3:89–92. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(68)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer EG, Gibson S, Wada JA, McGeeb PL. Distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase activity in adult and developing brain. Can J Biochem. 1967;45:1943–1952. doi: 10.1139/o67-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller RA, Thoenen H, Axelrod J. Adrenal tyrosine hydroxylase: Compensatory increase in activity after chemical sympathectomy. Science (Washington) 1969;158:468–469. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3866.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio JM, Julou L, Kety SS, Glowinski J. increase in rat brain tyrosine hydroxylase activity produced by electroconvulsive shock. Proc Nat Acad Sci (USA) 1969;63:1117–1119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.63.4.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatsu T, Levitt M, Udenfriend S. A rapid and simple radio assay for tyrosine hydroxylase activity. Anal Biochem. 1964;9:122–126. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(64)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter CC, Totaro JA, Stone CA. Effect of 6-hydroxydopamine and some other compounds on the concentration of norepinephrine in the hearts of mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1963;140:308–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanberg SM, Schildkraut JJ, Breese GR, Kopin IJ. Metabolism of normetanephrine in rat brain: Identification of conjugated 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol as the major metabolite. Biochem Pharmacol. 1968;17:247–254. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(68)90330-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanberg SM, Schildkbaut JJ, Kopin IJ. The effects of psychoactive drugs 911 norepinephrine-H3 metabolism in brain. Biochem Pharmacol. 1967;16:393–399. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(67)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildkraut JJ, Schanberg SM, Breese GR, Kopin IJ. Norepinephrine metabolism and drugs used in the affective disorders: A possible mechanism of action. Amer J Psychiat. 1967;124:600–608. doi: 10.1176/ajp.124.5.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedvall GC, Weise VK, Kopin IJ. The rate of norepinephrine synthesis measured in vivo during short intervals; influence of adrenergic nerve impulse activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968;159:274–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SH, Axelrod J, Zweig M. A sensitive and specific fluorescence assay for tissue serotonin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1965;14:831–835. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(65)90102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoenen H, Tranzer JP. Chemical sympathectomy by selective destruction of adrenergic nerve endings with 6-hydroxydopamine. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmakol Exp Pathol. 1968;261:271–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00536990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranzer JP, Thoenen H. An electron microscopic study of selective, acute degeneration of sympathetic nerve terminals after the administration of 6-hydroxydopamine. Experientia (Basel) 1968;24:155–156. doi: 10.1007/BF02146956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traylor TD, Bbeese GR. Brain tyrosine hydroxylase activity and catecholamine content after intracisternally (I.C.) administered 6-hydroxydopamine (60HDA) to rats. Fed Proc. 1970;29:511. [Google Scholar]

- Ungebstedt U. 6-Hydroxydopamine induced degeneration of central monoamine neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 1968;5:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(68)90164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uretsky NJ, Iversen LL. Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine on noradrenaline-containing neurons in the rat brain. Nature (London) 1969;221:557–559. doi: 10.1038/221557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uretsky NJ, Iversen LL. Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine on catecholamine neurones in the rat brain. J Neurochem. 1970;17:269–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1970.tb02210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtman RJ, Axelrod J. A sensitive and specific assay for the estimation of monoamine oxidase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1964;12:1439–1440. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(63)90215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]