SYNOPSIS

In September 2008, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sponsored a meeting of public health and infection-control professionals to address the implementation of surveillance for multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs)—particularly those related to health care-associated infections. The group discussed the role of health departments and defined goals for future surveillance activities. Participants identified the following main points: (1) surveillance should guide prevention and infection-control activities, (2) an MDRO surveillance system should be adaptable and not organism specific, (3) new systems should utilize and link existing systems, and (4) automated electronic laboratory reporting will be an important component of surveillance but will take time to develop. Current MDRO reporting mandates and surveillance methods vary across states and localities. Health departments that have not already done so should be proactive in determining what type of system, if any, will fit their needs.

A core function of public health agencies is disease surveillance, which has historically focused on communicable diseases in the community setting. In recent years, increased attention has been focused on implementing surveillance programs for multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs), including those related to health care-associated infections (HAIs). A notable example is the heightened interest in the state-based reporting of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)—an MDRO pathogen that is transmitted within and between health-care facilities, as well as in the community setting.

A voluntary method for conducting hospital-based HAI surveillance, the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System was started by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1970 and replaced in 2005 by the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), which allows all other types of health-care facilities to also participate.1 Information on antimicrobial use and resistance related to HAIs is a component of NHSN. In 2004, Pennsylvania became the first state to require hospitals to report HAIs.2 Now, 28 states have laws mandating public reporting of HAI rates.3 The types of HAIs reported and the surveillance methods used vary by state.2

Some state-based MDRO surveillance activities predate the more recent state-level focus on HAI surveillance, and their objectives and methods have also varied across states and over time. New Jersey initiated the first statewide hospital laboratory-based surveillance system for antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in 1991 to monitor various community-associated and health care-associated pathogens.4,5 Concerns about increasing antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae led several states to evaluate methods of MDRO surveillance in the late 1990s and thereafter.6–9 More recently, attention has focused on MRSA, with 11 states enacting laws requiring MRSA reporting.10

MRSA and other MDROs of public health concern can pose problems in acute and non-acute health-care settings. In fact, settings outside of acute care have been identified as reservoirs of MDROs that can introduce difficult-to-treat pathogens, such as carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, into acute care settings where patient-to-patient transmission can also occur. Detecting and monitoring MDROs in these areas of health-care delivery—outside the scope of traditional hospital-based surveillance and prevention efforts—can be facilitated by state and local health departments. Although specific pathogens, such as MRSA, have been the focus of some state-based surveillance efforts to date, the infection-control community and public health authorities recognize that other pathogens also require a comprehensive approach to prevent transmission and infection of patients throughout the spectrum of health-care delivery. To better define a reasonable approach to state-based MDRO surveillance, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) and CDC convened a meeting to share experiences of such programs and discuss goals for future MDRO surveillance activities at state and local health departments.

OBJECTIVES AND PARTICIPANTS

On September 22 and 23, 2008, public health and infection-control professionals with experience in MDRO surveillance related to city or state health department activities gathered in Atlanta, Georgia, for a meeting cosponsored by CSTE and CDC, and organized by CDC's Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. Participants included representatives of eight state health departments, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, and CDC.

The objectives of the meeting were to (1) identify issues relevant to public health authorities through sharing experiences from state-based reporting of MDROs and HAIs, (2) define a reasonable and effective framework for state-based MDRO surveillance that would inform meaningful prevention and intervention activities, and (3) prioritize essential activities of state or local health departments for surveillance of HAIs, including MDROs.

This article summarizes the main points identified and the ideas expressed by the meeting participants during facilitated discussion sessions.

RESULTS

General principles

A primary aim of public health surveillance is to direct prevention and control activities and monitor their effectiveness. Collection of surveillance data by itself does not control disease or constitute public health action. As public health agencies operate with finite resources, implementation of surveillance tools should occur in conjunction with a plan to interpret and act on the data collected. Resources should be devoted to MDRO surveillance activities only when resources are also available for specific MDRO infection- or transmission-prevention activities or to build capacity to respond with public health action to the MDRO surveillance data. Moreover, integrating input from local partners and key opinion leaders in infection control and prevention to ensure that any surveillance and response strategy is consistent with regional priorities or concerns is critical. A state is more likely to develop a surveillance system that meets its particular needs and functions well within the constraints of its available resources if the state health department takes an active role in deciding what MDRO surveillance activities are appropriate for its circumstances. Surveillance activities developed in response to mandates created without health department input could lack these characteristics.

Role of the health department

The details of case- or patient-level information necessary for MDRO reporting to public health agencies depend on several factors and vary by the specific MDRO. Very rare MDROs, such as vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA), should include comprehensive reporting (i.e., all potential cases reported) coupled with an outbreak investigation to help contain spread and assist infection-control efforts. Such case-based reporting includes the collection of detailed demographic and clinical information about infected individuals to guide this response and evaluate potential clusters or transmission among health-care communities. This type of case-based reporting is commonly used for diseases included on the list of Nationally Notifiable Diseases. In the case of MDROs, the frequency of occurrence and the necessity of a public health response to the MDRO incident must be considered to avoid requiring ongoing reporting of frequent events unlinked to any coordinated public health or infection-control response. Case-based reporting can be a time-consuming and labor-intensive process because of the need to collect detailed information about each person with the disease or condition.

When an MDRO of interest has become established or endemic in a city, state, or region, obtaining detailed information about patients infected with the MDRO through public health investigation or case reporting may not be needed to implement effective prevention and control measures. The exact incidence or prevalence of an MDRO in a population above which mandatory reporting becomes too burdensome is not simple to determine and must take into account the pathogen's transmissibility, infectivity, and associated morbidity and mortality. Therefore, not all MDROs of epidemiologic importance or public health interest should be added to lists of notifiable diseases or require detailed case reporting to public health departments. The detection and control of MDROs in community and health-care settings can occur without mandatory reporting. For example, data on HAIs voluntarily reported to the NNIS System documented a 68% decrease in the incidence of central line-associated bloodstream infections among intensive care unit patients in Pennsylvania from 2001 to 2005.11 In the community setting, outbreaks of community-associated MRSA have been identified in the absence of mandatory reporting by various public health authorities who led successful infection-prevention interventions.12–15

Regarding MDROs that are somewhat common or are well established in a community, surveillance activities should focus on assessing infection rates and trends in these rates, identifying risk factors for infection, and monitoring the effectiveness of infection-prevention or transmission-interruption interventions. One area where this type of information is critically needed is in evaluating the role that health-care facilities other than short-stay acute care hospitals play in the transmission, propagation, and emergence of MDROs. Periodic evaluations in non-acute care settings may identify potential reservoirs of MDROs and could help guide the design of necessary studies. Such focused studies addressing these issues could be completed within the framework of existing programs (such as the activities of the Emerging Infections Program) in states that already have MDRO surveillance activities in place, and in conjunction with outbreak investigations. These types of focused studies will benefit stakeholders beyond their geographic areas and do not need to be replicated in all states or localities.

Relationship between the health department and health-care facilities

State and local health departments are the only entities with the authority and resources to respond to infections involving MDROs in the community setting, as well as those involving people residing in institutions outside health-care facilities. The role of the health department in responding to MDRO issues occurring within health-care facilities, however, has been less clearly defined because, historically, hospital epidemiologists and infection preventionists took responsibility for monitoring and controlling MDROs within individual acute care facilities. Additionally, the frequent movement of patients (and their colonizing or infecting MDROs) between acute care inpatient settings and non-acute care or outpatient facilities has made understanding the transmission of MDROs difficult. More information is needed about effective and appropriate prevention and infection-control measures that should be used at the interface between acute care hospitals and other health-care settings (such as long-term care facilities, ambulatory surgical centers, and outpatient dialysis centers) and the community; health departments can serve a role in assessing these measures in these settings. Second, health departments could have a role in the research, prevention, and control of community-onset MDRO infections in individuals whose infections may be related to previous exposure to the health-care environment. Working across acute care facilities to develop a communication system to provide accurate information about MDROs of concern among patients moving between facilities is one example.

Health departments often provide assistance for outbreak control within both acute and non-acute health-care facilities. However, not all health departments have infection-control expertise or the resources to provide such assistance. Significant investment in training staff or reliance on local experts in consulting roles would be required for this expertise to be commonplace among health departments. Variability in the level of this expertise and resource commitment also exists because states differ with regard to whether this function is housed under the regulatory or the epidemiology branch of their health departments. The amount of involvement that a state or local health department should take within acute care facilities is not static and varies between jurisdictions, depending on local resources and needs.

Regarding common infections, including MDROs but also for HAIs in general, the group agreed that it would be beneficial if state health departments were involved in the evaluation of data reported from health-care facilities within their jurisdiction. If the health department will have the responsibility for analyzing these data, then it must be able to devote adequate resources to this work. Ideally, the health department should also have a role in determining the surveillance system that collects the data. CDC's NHSN is an established system that provides a standardized method for HAI and MDRO reporting, which some health-care facilities are already using to share their data with state health departments. The specific reporting requirements and dissemination of data collected using NHSN and other mechanisms currently differ by state, and these issues were not addressed by the meeting participants. Some participants expressed reservations regarding public reporting of facility-specific rates, citing the need for appropriate risk adjustment of data, which is an area requiring further research. Other participants viewed the dissemination of these types of data by public health authorities as appropriate and one of several tools in facilitating improvements in patient safety and prevention of HAIs in all types of facilities. Preventing and controlling MDRO infections outside of acute care facilities requires collaboration among all types of health-care facilities and health departments. The health department's key functions should include facilitating the sharing of information, coordinating risk assessments, and working with regulatory agencies.

In summary, health departments and health-care facilities should partner on MDRO surveillance and prevention activities and, ideally, these activities should include information sharing across the continuum of care from both acute care and non-acute care facilities.

Current state- or city-based surveillance activities

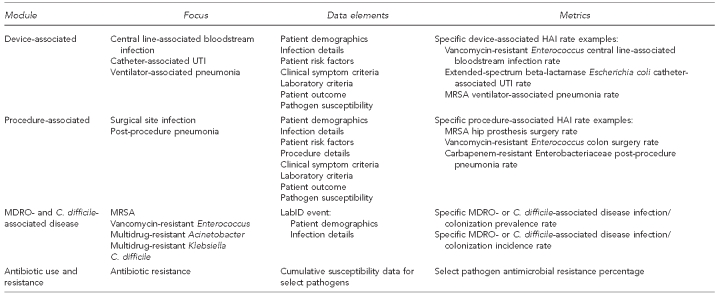

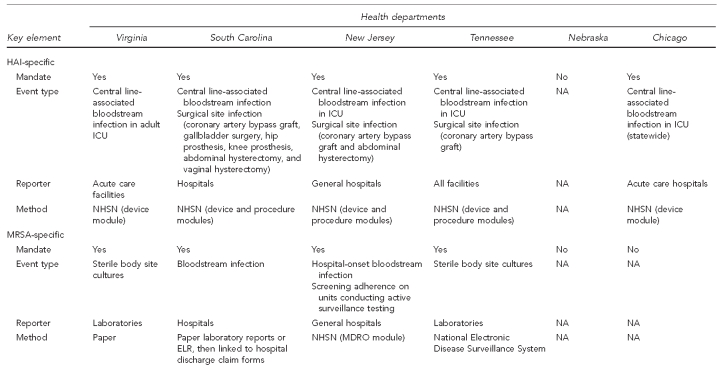

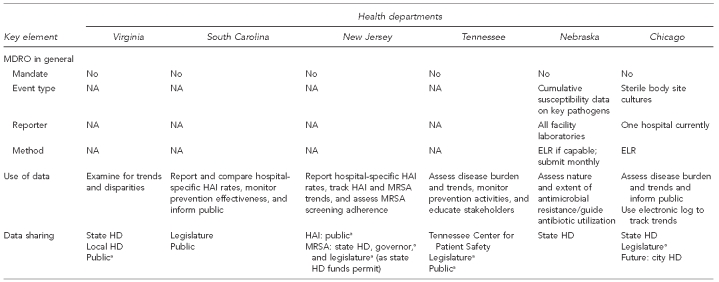

Representatives of five state health departments and one city presented summaries of the current HAI- and MDRO-related surveillance activities occurring in their jurisdictions. Five of the six jurisdictions have a requirement mandating reporting of HAI cases to the state health department; four of these mandates included MRSA. The surveillance mechanisms discussed included manual laboratory-based case reporting, electronic laboratory reporting (ELR), utilization of hospital discharge claims data along with laboratory reports, aggregation of cumulative antimicrobial susceptibility data, and the use of CDC's NHSN (Figure 1). Use of these data by the state health departments varied and included counting cases, tracking trends, identifying disparities in incidence among population groups, informing the public (consumers), educating stakeholders with local-level data, and publicly reporting hospital-specific rates (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

NHSN Patient Safety Component surveillance modules—focus, data elements, and metrics

NHSN = National Healthcare Safety Network

HAI = health care-associated infection

UTI = urinary tract infection

MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

MDRO = multidrug-resistant organism

C. difficile = Clostridium difficile

Figure 2.

Summary of key elements for HAI and MDRO surveillance from six health departments, as of September 22, 2008

aSummary data only

HAI = health care-associated infection

MDRO = multidrug-resistant organism

ICU = intensive care unit

NA = not applicable

NHSN = National Healthcare Safety Network

MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

ELR = electronic laboratory reporting

HD = health department

An ideal surveillance system

Because many MDRO surveillance activities already exist in various states and localities, any new MDRO surveillance system that is developed should utilize and create linkages between existing data sources. The development of any new surveillance system for MDROs should not be limited to one pathogen alone, but should be an adaptable framework that can be used to receive data on various MDROs as circumstances and needs change over time. Due to the changing nature of MDROs and the change of pathogens of concern, the goal of surveillance may evolve over time. One goal is the early detection of emerging organisms in a region or emerging antimicrobial resistance in an established organism. Other goals are to detect outbreaks or guide control and eradication efforts. For endemic MDROs, the goal of surveillance might be incidence reporting and trend analysis. Surveillance systems can also be used to identify patients for inclusion in epidemiologic studies and to collect organism isolates for laboratory investigation. A surveillance system should be designed to achieve its intended purpose in an effective and efficient manner.16 There is not a single best method to address these broad goals for MDRO surveillance; however, there was agreement among participants that investment in the use of electronic reporting of data elements from hospital or laboratory information systems would provide a flexible framework to address most, if not all, of the goals of MDRO surveillance.

Identification of MDROs requires laboratory data—specifically, antimicrobial susceptibility test results. The implementation of automated ELR will potentially allow for an efficient process of population-based reporting. The benefits of ELR include the ability to address both community- and hospital-onset infections; the ability to limit the resources needed for data entry; a reduction in reporting delays, previously due to all manual extraction and entering of laboratory data; the availability of a wide range of data; the ability to detect more than just invasive infections; and the adaptability of an infrastructure that is not organism specific. ELR does, however, have limitations. Specifically, implementation and maintenance require sufficient funding, widespread use does not currently exist in most states, and all laboratories must format data in a standardized manner.

An ideal surveillance system for MDROs would incorporate automated ELR but require more data than ELR alone can provide. For example, ELR alone does not provide information about risk factors and cannot guide interventions. Further work is needed to link laboratory results with claims data or specialized case-based reporting to improve health department understanding of health-care exposures leading to infection. Also needed are evaluations of the utility of algorithms based on electronic data elements to inform surveillance data.

The development of ELR as part of a systematic surveillance effort by public health authorities will require substantial work by health departments, health-care facilities, and their reporting laboratories. Currently, standardized vocabulary for the critical test results is available but is typically not being used in laboratory information systems. Also, standards for the messaging of electronic data continue to evolve. As standards become established and incorporated into the various products offered by vendors supplying health-care information technology for the management of infection-control or patient-care activities, capturing and conveying standard data elements could become an integral part of state-based efforts. ELR for reporting HAI data should be integrated with ELR for reporting notifiable disease data so that common infrastructure and data standards serve both purposes.

Recommended surveillance activities using existing resources

Because a new, integrated MDRO surveillance system that includes automated ELR will take time to develop, state health departments should consider which MDRO surveillance activities should be pursued immediately. As stated previously, it is important to integrate input from local health-care partners and key opinion leaders in infection control to ensure any surveillance and response strategy is consistent with regional priorities or concerns. Additionally, the health department should provide feedback based on the surveillance activities to reporting facilities and other stakeholders. Dedicated support should be aimed at specific MDRO infection- or transmission-prevention activities. For common MDROs that are well established in a community, surveillance activities should focus on assessing infection rates and trends in those rates, identifying risk factors for infection, and monitoring the effectiveness of infection-prevention or transmission-interruption interventions.

For those jurisdictions that do not currently have ELR capability, the meeting participants recommended that health departments planning to implement surveillance for MDROs limit their surveillance to blood culture isolates if the MDRO is common (e.g., MRSA). Isolation of MRSA on blood culture has been shown to correlate with infection, whereas organisms cultured from non-sterile body sites, such as skin, could represent colonization.4 If a jurisdiction does have ELR capability, the state health department could expand the culture results to include both normally sterile and non-sterile body sites to utilize and report several types of metrics that are outlined in the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee position paper on measuring MDROs in health-care facilities.17

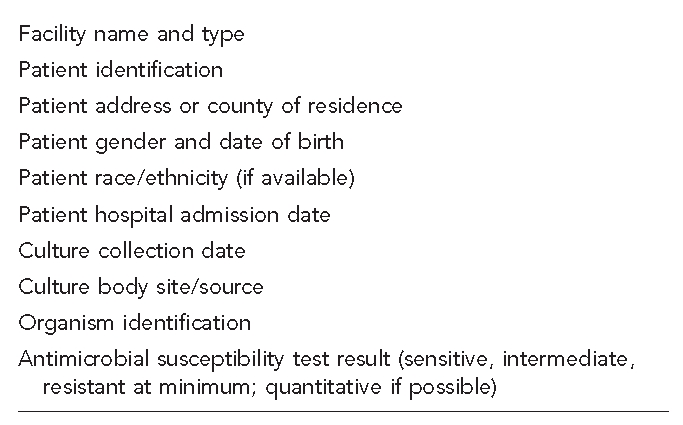

Consideration should be given to which laboratories will be required to provide information. To achieve the most complete surveillance of both health care- and community-associated MDRO infections, it would be necessary to include all laboratories that serve a state's population, whether located inside or outside the state. Both hospital-based and non-hospital-based laboratories would be included. Depending on the goals of a state's MDRO surveillance system and the resources available, reporting by only a subset of all possible laboratories might be sufficient, such as in a sentinel surveillance system. The minimum data elements that should be collected for MDRO surveillance in any system are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Minimum data elements to consider in multidrug-resistant organism surveillance

CONCLUSIONS

With limited resources, any surveillance program needs to be of high value at low cost. Resources for MDRO surveillance should not be diverted from existing priority activities. As the public health importance of MDROs related to health-care delivery increases, weighing the costs and benefits for establishing a new reporting system will be challenging but necessary. In all likelihood, new resources will be required. Of great importance, health departments should avoid collecting MDRO-related data for which they lack the resources to analyze or act upon.

Without adequate resources for establishing a viable surveillance system, public health authorities may choose to focus solely on prevention and infection-control activities. When pursuing activity in this arena, health departments should take great effort to involve local opinion leaders and key partners to ensure that surveillance and prevention work is not duplicative with facility-specific activities.

The focus for individual states and the nation as a whole should be on developing a surveillance system infrastructure for all significant MDROs and not on creating systems that address just a single organism. Any new system should utilize and link information available in existing systems to build on current efforts and maximize efficiency. An ideal infrastructure will integrate information from national, state, and local levels. Development and implementation of automated ELR are important components of a successful and comprehensive surveillance infrastructure for MDROs. A strategic plan for developing this infrastructure would aid in the planning and implementation of such a system.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following individuals for their participation in the meeting: Kathleen Arias (Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology); Sandie Bulens, Denise Cardo, Jonathan Edwards, Rachel Gorwitz, Jeff Hageman, Mary Hamilton, Teresa Horan, John Jernigan, Brandi Limbago, Cliff McDonald, Jean Patel, Ruby Phelps, Dan Pollock, Chesley Richards, and Melissa Schaefer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion); James Hadler (Connecticut Department of Public Health); Shauna Onofrey (Massachusetts Department of Public Health); Tom Safranek (Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services); Corey Robertson (New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services); Rachel Stricof (New York State Department of Health); Neil Fishman (Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America); Jerry Gibson and Dixie Roberts (South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control); Bala Hota (Stroger Hospital and Rush University Medical Center); Dan Diekema (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics); Mike Edmund (Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center); Chris Novak (Virginia Department of Health); and John Stelling (World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance, Brigham and Women's Hospital).

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tokars JI, Richards C, Andrus M, Klevens M, Curtis A, Horan T, et al. The changing face of surveillance for health care-associated infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1347–52. doi: 10.1086/425000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier BM, Stone PW, Gebbie KM. Public health law for the collection and reporting of health care-associated infections. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:537–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. HAI reporting laws and regulations. [cited 2010 May 21]. Available from: URL: http://www.apic.org/downloads/legislation/HAI_map.gif.

- 4.Paul SM, Finelli L, Crane GL, Spitalny KC. A statewide surveillance system for antimicrobial-resistant bacteria: New Jersey. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:385–90. doi: 10.1086/647135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statewide surveillance for antibiotic-resistant bacteria—New Jersey, 1992–1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(27):504–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jernigan DB, Kargacin L, Poole A, Kobayashi J. Sentinel surveillance as an alternative approach for monitoring antibiotic-resistant invasive pneumococcal disease in Washington State. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:142–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell N. Antibiotic resistance: the Iowa experience. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:988–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castrodale L, Hennessy T. Combined antibiogram for hospitals with 50+ beds—Alaska, 2002. Alaska Med. 2004;46:81–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauner DG, Roberts DF, Kotchmar GS. Statewide sentinel surveillance for antibiotic nonsusceptibility among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in South Carolina, 2003–2004. South Med J. 2007;100:14–9. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000232968.56740.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. MRSA laws and pending legislation—2010. [cited 2010 May 21]. Available from: URL: http://www.apic.org/am/images/maps/mrsa_map.gif.

- 11.Reduction in central line-associated bloodstream infections among patients in intensive care units—Pennsylvania, April 2001–March 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(40):1013–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in correctional facilities—Georgia, California, and Texas, 2001–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(41):992–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections among competitive sports participants—Colorado, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Los Angeles County, 2000–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(33):793–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorwitz RJ. Understanding the success of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains causing epidemic disease in the community. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:179–82. doi: 10.1086/523767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zinderman CE, Conner B, Malakooti MA, LaMar JE, Armstrong A, Bohnker BK. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among military recruits. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:941–4. doi: 10.3201/eid1005.030604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.German RR, Lee LM, Horan JM, Milstein RL, Pertowski CA, Waller MN. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR-13):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen AL, Calfee D, Fridkin SK, Huang SS, Jernigan JA, Lautenbach E, et al. Recommendations for metrics for multidrug-resistant organisms in healthcare settings: SHEA/HICPAC position paper. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:901–13. doi: 10.1086/591741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]