SYNOPSIS

Objectives

Information that would allow the identification of women who were pregnant at the time of death or within the year preceding death has historically been underreported on death certificates. As a result, the magnitude of the problem of pregnancy-associated mortality is underestimated. To improve the identification of these deaths, check boxes for reporting pregnancy status have been added to death certificates in a number of states. We used multiple external data sources to determine whether check boxes have been effective in identifying pregnancy-associated deaths.

Methods

We collected data on deaths occurring among pregnant or recently pregnant women residing in Maryland during the years 2001–2008 using multiple data sources. We determined the percentage of these deaths that could be identified through check boxes placed on death certificates.

Results

Overall, 64.5% of pregnancy-associated deaths were identified through pregnancy check boxes on death certificates, including 98.1% of maternal deaths—defined as deaths occurring during pregnancy or within 42 days of delivery from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes—and 46.7% of deaths from nonmaternal causes, such as homicide, suicide, accidents, and substance abuse.

Conclusions

Check boxes on death certificates are effective in identifying pregnancy-associated deaths resulting from maternal causes. However, they are far less effective in identifying deaths resulting from nonmaternal causes, such as homicide, accidental death, and substance abuse, which represent three of the four leading causes of pregnancy-associated death in Maryland.

The term “pregnancy-associated death” was introduced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with the Maternal Mortality Special Interest Group of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, to define a death from any cause during pregnancy or within one calendar year of delivery or pregnancy termination, regardless of the duration or anatomical site of the pregnancy.1 Pregnancy-associated deaths include deaths commonly associated with pregnancy, such as hemorrhage, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and embolism, as well as deaths not traditionally considered to be related to pregnancy, such as accidents, homicide, and suicide.

Previous studies have shown that physicians completing death records fail to report that a woman was pregnant or had a recent pregnancy in 50% or more cases.2–5 As a result, these deaths cannot be identified as being associated with pregnancy. Because death records collected by the states are the source of data used to compute published state and national pregnancy-associated mortality rates, these rates and the problem of pregnancy-associated mortality are considerably underestimated.

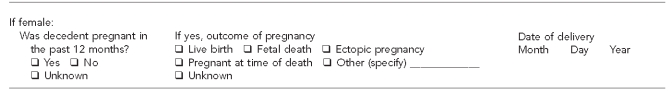

In response to the problem of underreporting of pregnancy-associated deaths, the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death, which the states use as a guide in developing their death certificates, was revised in 2003 to include, among other changes, the addition of a question for female decedents on pregnancy status in the year preceding death (Figure 1). Inclusion of this question on the death certificate was recommended by the Panel to Evaluate the U.S. Standard Certificates and Reports and was consistent with a recommendation of the World Health Assembly in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10).6

Figure 1.

Pregnancy item on the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death

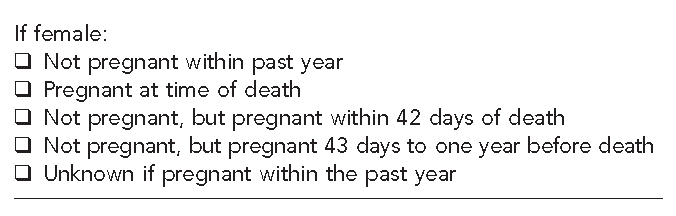

The Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DHMH) has had a program in place for enhanced surveillance of pregnancy-associated deaths since 1993 and has been collecting detailed information on pregnancy status on Maryland death certificates since 2001. In addition to the check box asking if a female decedent was pregnant in the 12 months preceding death, the Maryland death certificate includes questions on the outcome of pregnancy and the date of delivery (Figure 2). Maryland DHMH also identifies pregnancy-associated deaths from other sources, including linkage of death records with birth and fetal death records and review of medical examiner records.5,7

Figure 2.

Pregnancy items on the Maryland Certificate of Death

The availability of comprehensive data collected from multiple sources provided the opportunity to study the effectiveness of check boxes on death certificates in identifying pregnancy-associated deaths. The few previous studies that have assessed the effectiveness of pregnancy check boxes did not use comprehensive, enhanced surveillance to identify all pregnancy-associated deaths, including deaths due to nonmedical causes, such as accidents, homicide, and suicide.8,9 The study by Comas et al. made the assumption that check boxes were marked on all death records that were pregnancy-associated and did not use any external sources to identify possible missing cases.8 The study by MacKay et al. used records obtained from state vital records offices, few of which use enhanced surveillance techniques to ensure that all pregnancy-associated deaths are identified. As a result, the dataset was incomplete.9

METHODS

We collected data on pregnancy-associated deaths occurring during the years 2001 through 2008 from three main sources: (1) a review of death certificates to identify those records on which the pregnancy check box was checked or a complication of pregnancy, childbirth, or the puerperium (ICD-10 codes O00-O99) was listed as an underlying or contributing cause of death (COD); (2) linkage of death certificates of reproductive-age women with corresponding live birth and fetal death records to identify a pregnancy within the year preceding death; and (3) a review of medical examiner records for evidence of pregnancy at the time of death or evidence of a recent pregnancy. In addition, we identified deaths through newspaper articles, obituaries, and reports from hospital staff and local health departments.

We obtained vital records data from the Vital Statistics Administration of the Maryland DHMH. We accomplished identification of pregnancy-associated deaths through linkage of vital records by matching death certificates for all women between the ages of 10 and 50 years against live birth and fetal death records to identify pregnancies occurring in the year preceding death. We achieved successful linkage of records by matching either the mother's social security number or mother's name and date of birth on the death record with corresponding information on live birth and fetal death records. We reviewed all linked records manually to ensure accurate matching of records. We reviewed medical examiner records, which include autopsy reports and police records, for women of reproductive age who died during the study period. Maryland law mandates that the medical examiner investigate all deaths that occur by violence, suicide, casualty, unexpectedly, or in any suspicious or unusual manner. We obtained death certificates for all women for whom medical examiner records indicated evidence of pregnancy.

Records that did not contain a marked check box or indication of a maternal COD were reviewed by a board-certified obstetrician/gynecologist and two certified nosologists to determine the ICD-10 code of the underlying COD that would have been assigned if a history of pregnancy had been reported on the death certificate. Each pregnancy-associated death was classified as either a maternal or nonmaternal death based on standard definitions. A maternal death is defined as a death “while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes.”10 A nonmaternal death is a death occurring from (1) an incidental cause or an injury while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy or (2) a death from any cause occurring 43 to 365 days following delivery or pregnancy termination.

We reviewed all death records to determine whether pregnancy status was reported. We examined the percentage of maternal and nonmaternal death records with marked check boxes by time of death, pregnancy outcome, COD, maternal age, and maternal race.

RESULTS

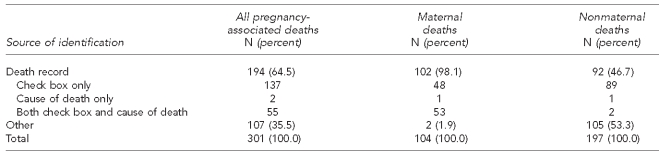

We identified 301 pregnancy-associated deaths occurring among Maryland residents during the years 2001–2008. We identified 194 of these records (64.5%) through information reported on Maryland death certificates, including 137 through a marked pregnancy check box, two through COD information, and 55 through both a marked pregnancy check box and COD information (Table 1). Check boxes were considered to be marked on the two certificates that reported pregnancy through COD information alone, as pregnancy status was clearly indicated.

Table 1.

Pregnancy-associated deaths by subgroup and source of identification, Maryland, 2001–2008

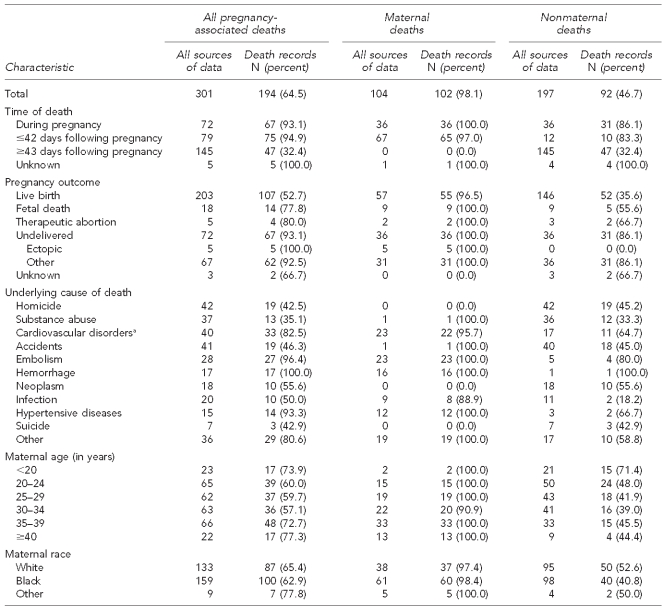

Check boxes were marked on nearly all certificates of women whose deaths were classified as maternal deaths (98.1%), but on fewer than half (46.7%) of certificates of women whose deaths were determined to be from nonmaternal causes. The percentage of maternal death records with marked check boxes was close to 100% regardless of time of death (during pregnancy vs. following pregnancy), outcome of pregnancy, COD, maternal age, or maternal race (Table 2). In contrast, the percentage of death records with marked check boxes for women who died of nonmaternal causes varied by time of death, outcome of pregnancy, COD, and maternal age and race. More than 80% of records of women who died from nonmaternal causes either during pregnancy or within 42 days postpartum had marked check boxes, compared with the records of only 32.4% of women who died 43–365 days postpartum. In terms of pregnancy outcome, check boxes were marked on the records of 86.1% of women who died of nonmaternal causes while pregnant, compared with 55.6% of the records of women who died following a fetal death and 35.6% of records of women who died following a live birth. The likelihood that check boxes were marked on the records of women dying as a result of nonmaternal causes also varied widely by the underlying COD.

Table 2.

Pregnancy-associated deaths by subgroup, source of identification, and selected pregnancy and death characteristics, Maryland, 2001–2008

aIncludes cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, endocarditis, valvular dysfunction, and other cardiac conditions related to or aggravated by pregnancy

With the exception of infections, check boxes were more frequently marked on the death records of women who died as a result of medical conditions, such as hemorrhage, embolism, hypertensive diseases, and cardiovascular disorders, than on the records of women who died as a result of nonmedical causes, such as homicide (45.2%), accidental death (45.0%), suicide (42.9%), or substance abuse (33.3%). Check boxes were more frequently marked on the death records of teenagers (71.4%) who died of nonmaternal causes than on the records of older women (43.8%) who died of nonmaternal causes, and more likely to be marked on the records of white women (52.6%) than black women (40.8%).

DISCUSSION

Despite the addition of check boxes to the Maryland death record to collect information on pregnancy status in the year preceding death, 35.5% of pregnancy-associated deaths occurring during the study years—nearly all from nonmaternal causes—could not be identified using death certificate information alone. Although this figure represents a substantial improvement over the 72.9% of pregnancy-associated deaths that were unreported on death records in a study conducted in Maryland prior to the addition of the check box,5 more than one-third of all pregnancy-associated deaths remain unreported, suggesting that identification of all pregnancy-associated deaths is likely to continue to require the collection of data from data sources in addition to the death record.

Check boxes were extremely effective in identifying pregnancy-associated deaths resulting from maternal causes. More than 98% of maternal deaths occurring in the years 2001–2008 were identified on death records, compared with only 62% in the eight-year period before check boxes were added to the Maryland death certificate.7

Check boxes were far less effective in identifying pregnancy-associated deaths from maternal causes, which in Maryland were the leading causes of pregnancy-associated death. While death certificate data alone indicated that the leading causes of pregnancy-associated death were cardiovascular disorders and embolism, data collected using enhanced surveillance methods showed that the actual leading CODs were homicide and motor vehicle accidents.

Data on pregnancy mortality are collected from the states by two centers within CDC, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP). NCHS collects death certificate data from the states through the National Vital Statistics System and compiles and publishes maternal mortality data.11 If the pregnancy check boxes used by other states are as effective as the Maryland questions, the completeness of national maternal mortality data should improve greatly once all states adopt the new certificate. As of August 2009, only half of the states were using the revised certificate due to lack of resources for implementation.12

NCCDPHP seeks to obtain a broader range of pregnancy mortality data by requesting that the states voluntarily submit for inclusion in the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS) not only maternal death records, but also death records for nonmaternal pregnancy-associated deaths and copies of other materials that might be available, including maternal mortality review summaries, autopsy reports, case reports, and hospital records.13 Although some states have enhanced surveillance methods in place to collect comprehensive pregnancy-associated death data or the additional information requested by PMSS, most do not. Because the check boxes identify fewer than half of all nonmaternal deaths occurring 43–365 days after delivery, the information available in the PMSS is likely to continue to be incomplete even after all states adopt the revised death certificate. Because homicide, accidental death, and substance abuse are three of the four leading causes of pregnancy-associated death overall, the underreporting of this information is a serious concern.

An issue that complicates the collection of complete, uniform pregnancy mortality data is that nearly half of the states with pregnancy questions on their death certificates ask the question in a way that does not conform to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death. The intent is for states to collect information on all deaths occurring during pregnancy or within one year of delivery or pregnancy termination. The Maryland questions do this, albeit in more detail than required by national standards. However, some states collect information only on deaths occurring during a shorter postpartum period, ranging from 42 days to six months (Unpublished data, National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems, 2009).

CONCLUSIONS

Although maternal mortality rates have fallen dramatically during the past century, young, apparently healthy women continue to die as a result of medical conditions related to pregnancy, as well as a result of a broader range of factors that may be related to pregnancy, such as homicide, suicide, and substance abuse.5 The inclusion of pregnancy check boxes on death certificates greatly improves the completeness of data for deaths resulting from maternal causes; that is, deaths while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes. However, check boxes are less effective in identifying pregnancy-associated deaths resulting from nonmaternal causes, such as homicide, accidental death, and substance abuse, which represent the majority of pregnancy-associated deaths occurring in Maryland.

Effective strategies to prevent pregnancy-associated mortality from all causes are predicated on the availability of valid and reliable surveillance data. Both the states and CDC should continue efforts to improve the collection of complete and accurate pregnancy-associated death data. States should be encouraged to adopt the revised certificate, which will substantially improve the completeness of maternal death data, and to implement enhanced surveillance methods for identifying deaths resulting from nonmaternal causes. The use of additional sources of data to improve the identification of pregnancy-associated deaths, such as hospital discharge data, should be explored. The inclusion of pregnancy check boxes on death certificates is an important step, but cannot be the final step, in providing the surveillance data needed to formulate effective strategies for preventing pregnancy-associated deaths.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atrash HK, Rowley D, Hogue CJR. Maternal and perinatal mortality. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1992;4:61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dye TD, Gordon H, Held B, Tolliver NJ, Holmes AP. Retrospective maternal mortality case ascertainment in West Virginia, 1985 to 1989. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:72–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pregnancy-related mortality—Georgia, 1990–1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(5):93–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atrash HK, Alexander S, Berg CJ. Maternal mortality in developed countries: not just a concern of the past. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(4 Pt 2):700–5. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00200-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horon IL, Cheng D. Enhanced surveillance for pregnancy-associated mortality—Maryland, 1993–1998. JAMA. 2001;285:1455–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision, vol 1. Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horon IL. Underreporting of maternal deaths on death certificates and the magnitude of the problem of maternal mortality. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:478–82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.040063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maternal mortality surveillance—Puerto Rico, 1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40(30):521–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacKay AP, Rochat R, Smith JC, Berg CJ. The check box: determining pregnancy status to improve maternal mortality surveillance. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(1 Suppl):35–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009 Apr 17;57:1–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems. Electronic death registration systems by jurisdiction. 2009. Aug, [cited 2009 Aug 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.naphsis.org/NAPHSIS/files/ccLibraryFiles/Filename/000000001121/EDRS_Development_with_territories_August_2009.ppt#256,1,Slide1.

- 13.Chang J, Elam-Evans LD, Berg CJ, Herndon J, Flowers L, Seed KA, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance—United States, 1991–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2003;52(SS-02):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]