Community assessment—a gathering of information about a given community—is critical to understanding health issues at the grassroots level. Community assessment through data collection is an integral component of community health programming. Without proper assessment of a community's needs and assets, public health professionals are uninformed, underprepared, and may develop health programs that are potentially ineffective and irrelevant.1 Various tools are used to gather community data, from ethnographic observations to key informant interviews and surveys. While these tools remain an integral part of the public health toolbox, the information provided by such tools is not easily interpreted by the general public. Furthermore, such data often fail to reveal the direct correlation between geographic location and health.

More than 100 years ago, John Snow used maps to discover the source of the London cholera outbreak.2 Snow took what he knew of the health of individuals in the community and created outbreak maps, connecting the information to the individuals' geographic location, and eventually discovering the source of the epidemic. The modern application of Snow's methods, geographic information systems (GISs), is an existing tool applied to highlight community assets and display spatial patterns in a way that was not previously possible.3 GISs have been well documented as a tool that can collect, organize, retrieve, analyze, and display public health data in relation to place.4 (To better understand GIS capacity, consider global positioning satellite [GPS] devices in cars that use satellites to depict a given geographic location using X and Y coordinates.)

Maps produced from GIS data can be used to depict relationships and significant hotspots within a community. For example, researchers used GIS to determine if there was a relationship between environmental conditions and high-risk sexual behavior. They developed a “broken windows” index that referred to the level of deterioration of the surrounding environment. Through the use of census data and the collection of GIS coordinates, the researchers were able to reveal a significant association between deteriorated neighborhoods and rates of gonorrhea.5

Rather less documented, however, is the fact that GIS maps can be more user-friendly than other forms of data presentation, helping community-based organizations (CBOs) understand community data and facilitating a better understanding of the community. The result should be programs that can better address community needs.3

This article illustrates a case study of the application of GIS in a community assessment school project, showing the usefulness of GIS in mapping community needs and assets and in communicating the results to the community and its partners.

THE ADVANTAGES OF USING GIS

Studies have shown the effectiveness of using GIS software. For example, McLafferty and Grady studied the geographic distribution of women's health services provided by urban, community-based free clinics. GIS data revealed substantial gaps in health-care access among various racial/ethnic groups. Once the information was shared, community clinics reallocated their resources to reach more of the surrounding population.6

When CBOs operating in underresourced communities are given access to user-friendly data, they are better able to use the information to make evidence-based decisions for program planning. Aronson et al. tested this concept in a community assessment addressing infant mortality, using GIS mapping to gather data and engage residents in the health initiative. GIS mapping enabled the researchers to produce more accessible and understandable information for the residents.3

Choi et al. used GIS to identify environmental health risks in a Baltimore community. The researchers then surveyed patients at a nonprofit community clinic. Linking the survey information to GIS data, community stakeholders uncovered relationships between geographical location and environmental exposure. The researchers concluded that GIS mapping makes health information more accessible and easier for community stakeholders to interpret.7 Because public health programming hinges on information, the graphic depiction of data is invaluable, as it links health information to its geographical location. As a result, communities find new solutions to address public health problems.8

THE STUDENT ROLE

In fulfillment of a class assignment, public health graduate students at Loma Linda University decided to test the benefits of using GIS in community health projects and improve their GIS skills by conducting a case study in partnership with a CBO located in the Westside community of San Bernardino, California. Westside is an area of approximately four and a half square miles. Historically African American, the community's demographic has transitioned so that more than 70% of its population now claims Hispanic race/ethnicity.9 The university made arrangements to allow students to collaborate with the CBO to improve community programming.

When initially approached about working with the students, the CBO expressed reluctance to participate, as it was frustrated over not having access to the results of past assessments, rendering them unable to use the findings to improve community health programs (Personal communication, CBO Executive Director, October 2007). Instead, they relied on publicly available data, such as census data. Though hesitant, the CBO leadership agreed to collaborate with the public health students with the understanding that the students would provide copies of all the assessment data to the CBO upon completion of the project.

The students' first task was to perform comprehensive needs and assets-based assessments of both the Westside community and the CBO. When assessing the CBO, the students learned that its mission is broad and all-encompassing, but that it emphasizes providing social, spiritual, and physical support to the community, particularly young people.

The CBO and surrounding community have been the focal point of several assessments in the past due to their close proximity to multiple universities that wanted to collect data. Prior assessments never used GIS; rather, approaches to data collection were limited to subjective, qualitative methods involving surveys and key informant interviews. Although useful, these methods lacked the vivid and comprehensive assessment of a community's physicality that GIS provides.

An initial asset inventory revealed that the CBO had developed a number of programs—ranging from parenting and nutrition classes to life-skills training and activities for young people—that could benefit from GIS data. For example, a GIS map displaying the relative locations of supermarkets in the community could aid program planners in preparing for their nutrition classes. When conducting food demonstrations in supermarkets, CBO staff could view these data beforehand and make better decisions about which markets to visit depending on the residence of their program's attendees.

METHODS

Data collection

The GIS data collection was part of the community assessment; the goal was to highlight assets and needs that existed within the Westside community. However, to do this successfully, the students had to first perform a qualitative assessment of the CBO, the community residents, and the physical aspects of the community itself. Through the use of windshield surveys, key informant interviews, and ethnography, the students were able to identify areas of concern. This information guided the students as they collected the GIS data. While they recorded data points for each establishment and advertisement they observed in the community, the qualitative assessment information alerted them to specific areas.

In the past, data collection for community assessments was usually the result of the aforementioned methods and, thus, the primary way the students collected data points was through windshield surveys. However, the use of GIS added another dimension to the process. To conduct a community asset inventory, students used Trimble® Recon GPS units (Trimble Navigation Ltd., Sunnyvale, California) loaded with customized data dictionaries to collect spatial data points. Having an idea of what types of data might be obtained, students entered different categories to create the customized data dictionaries. Each GIS data point collected was entered in the GPS units under one of the following categories: health and safety, transportation and advertising, education, community asset, food security, and other. Data points included small businesses, hospitals, restaurants, transportation, and advertisements. Other data were collected for abandoned houses and environmental hazards. In addition, because of crime in this ZIP code, as reported from the San Bernardino City Police Department's official website, we collected data points for liquor stores and ammunition shops, which were perceived contributors to these reported data.10

Data analysis

After collecting data points, the students triangulated the data by contacting community residents and CBO staff, thereby ensuring reliability. As there was more than one team of students collecting data at any given time, all of the students compared the data post-collection to ensure that no duplicate data points were mapped and reported. Students then used Environmental Systems Research Institute ArcView® 9.2 GIS software to aggregate the data, create maps, and highlight findings.11

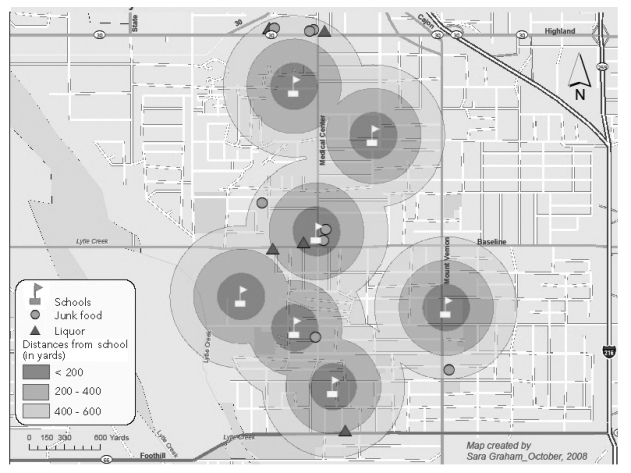

We used buffer functions to create a circumference of 600 yards around all Westside schools to determine the number of junk-food and liquor stores that fell within that area (Figure 1). Buffer functions are a feature of GIS software that allows one to create a radial area of a desired distance around specific data points to more easily identify relationships among the data with regard to distance. We initially used the base of 200 yards because that is the restriction placed on liquor stores by the state's Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC).12 However, we expanded the distance to 600 yards because that is considered a normal walking distance for the residents of this community, and the students wanted to display the probability of a child passing such a place on their daily commute to school.

Figure 1.

Unhealthy food choices around schools in the Westside neighborhood of San Bernardino, California, October 2008

We analyzed the data to highlight potential relationships that might exist with regard to the distance between unhealthy food establishments (e.g., liquor stores, convenience stores selling junk food, and fast-food restaurants) and Westside schools. Students theorized that the close proximity of these establishments to the schools was a direct contributor to health problems (e.g., obesity, diabetes, and heart disease), which, according to the CBO leadership, were known to be prevalent in the community.

RESULTS

When finished analyzing the data, the students presented the CBO leadership and staff with the results of the study, including copies of the maps created and a written report that explained the findings. By using GIS to display information gathered from the qualitative assessment, the staff were able to view this information graphically. For example, the students not only collected X and Y coordinates of a convenience store, but actually went inside and looked around, noting what goods were sold. Now a convenience store can be identified not only by its location on the map, but also by the type and quality of food and drink sold there, based on the descriptions students attached to that data point. These attributes can then be mapped and presented graphically. That is, a map can be created based on all the convenience stores that sell liquor.

In the weeks following the presentation, students interviewed the CBO staff to determine what knowledge had been acquired and how they believed the information could be applied. Staff were interviewed regarding the validity of the information displayed in the maps, their ability to interpret them, and their confidence in sharing them with other key stakeholders.

Outcomes

GIS maps created by students from the collected data revealed high numbers of what were termed by the students as junk-food establishments (i.e., fast-food restaurants and corner stores carrying predominantly unhealthy foods). Some of these establishments, including liquor stores, were within less than 200 yards of Westside schools, displaying a lack of healthy food choices for students in the community (Figure 1).

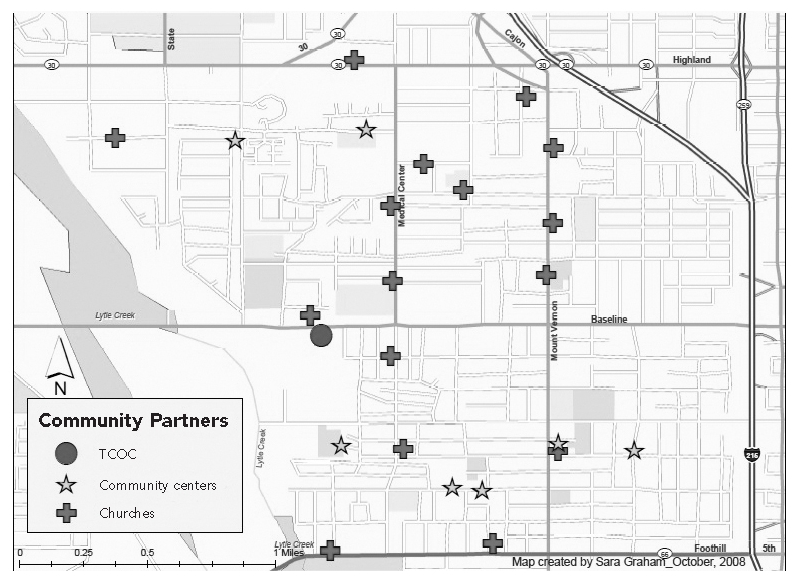

Concurrently, Figure 2 illustrates a substantial number of identified community assets, such as other CBOs and faith-based organizations. This map highlights potential partners with whom community-wide problems could be addressed.

Figure 2.

Key stakeholders in the Westside neighborhood of San Bernardino, California, October 2008

TCOC = Temple Community Outreach Center

Students also noted a high number of negative advertisements throughout the community. Advertisements for things such as bail bonds, gambling, and R-rated movies were prevalent. Certain environmental hazards were also recorded and the data shared with the stakeholders. These hazards mainly included abandoned lots tucked away within residential areas that contained harmful things such as broken glass and needles. While this dataset was not the primary focus of this research, it was brought to the CBO's attention.

Benefits for stakeholders and students

The Westside CBO was the primary beneficiary of the study. Much of the information gathered was new to the CBO leadership and staff, and they were surprised at the number of assets in their community. The maps revealed geographic details of the community that had escaped them, such as their program beneficiaries. The CBO director was pleased to discover that she had a clearer understanding of target populations and boundaries after studying the maps.

The CBO staff noticed visual correlations from the maps, including the number of liquor and convenience stores and their proximity to the community's schools. The ABC reserves the right to deny a liquor license to anyone wishing to build an establishment within 200 yards of a school, public playground, or nonprofit youth facility, especially if the proximity infringes upon the moral or peace-loving wishes of the community.12 This regulation places the responsibility on CBOs or other community entities to act in the best interests of their community. The maps stimulated the Westside CBO to begin work on shutting down some of these establishments.

Mapping the data and sharing it with the CBO put the organization in a stronger position to advocate for the community. CBO leaders had suspected there was a problem with the community's access to healthy food, but they were not able to visualize the extent of the problem. After analyzing the maps and reports, the CBO director could clearly see the barriers that existed, including an insufficient number of adequate supermarkets, a plethora of fast-food restaurants, and numerous junk-food establishments in residential areas and school zones. The CBO director then initiated a dialogue with other community stakeholders in an effort to address the issue around Westside schools.

The students also benefited from this case study. They gained experience in community assessment—using GIS as a main data collection tool—and a basic understanding of GIS and its purpose in public health community assessments. They learned how to collect spatial data; report their findings to peers, professors, local leaders, and stakeholders; and add GIS data collection and analysis to their academic skillset. Additionally, the students left behind a rich set of community data upon which future classes could build.

Reactions and new insights

When the GIS maps were presented to the CBO, the staff were excited to receive the results of the assessment and thanked the students for fulfilling their commitment to share the findings. This exchange helped promote an additional level of confidence, strengthening the partnership between the community and the university.13 Sharing the findings of the assessment with the CBO and the community is an essential part of community-based participatory research, a fundamental concept in public health. This type of research engages the community and its leaders, placing them in a position to make decisions based on their own data analysis. Community members can then promote the usage of the research findings.14 The result is more relevant health programs for the community.

The CBO leadership was not only enthusiastic about the maps themselves, but also about the content of the maps. They began to see how the GIS maps could provide them with evidential support for making decisions about health programming. The CBO Director noted, “The [GIS maps] showed me who the key players are [in Westside] and made me realize how much more we need to be working with other CBOs in this community.” The maps were viewed by the CBO as a useful tool that continues to be used to engage other community partners in problem solving. The CBO Director has already held a number of meetings with the Unified School District, local pastors, and other stakeholders to address food security issues affecting their community.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Data can be used to say any number of things. As public health professionals, we have to be careful when reporting data to present them precisely and objectively. Likewise, caution must be taken when reporting statistics. Students should be adequately trained to conduct research that presents the GIS data itself and not what the data suggest. The receivers of that information must be able to interpret it and draw their own conclusions.

Furthermore, it was shown how important it is for community leaders to be able to access this information and technology. However, there are limitations to this access. First, the elements required to use this technology are costly. To solve this problem, open-source software packages and more cost-effective types of equipment are under development. The second limitation is that community leaders would need to be educated in GIS technology before using it. This process is difficult but not impossible. Initially, external support would be required.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC HEALTH

The use of GIS in this project created avenues for change for local city officials and key community stakeholders. GIS technology is a powerful tool for public health professionals because it can be used to communicate important facts about a community.3 For example, bus routes can be plotted in communities in which personal transportation is a commodity, revealing something about residents' access to health care. Furthermore, GIS ties health to where people live. In the case of diabetes and obesity, these diseases are influenced not only by behavior and genetics, but also by the environment. GIS is a tool that accounts for this factor and can be used, for example, to expose relationships between cancer and air quality or ground contamination. Grassroots interventions might be more easily achieved as a result.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belliard JC, Dyjack DT. Putting the public into the public health curriculum: a case study. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:452–4. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scotch M, Parmanto B, Gadd CS, Sharma RK. Exploring the role of GIS during community health assessment problem solving: experiences of public health professionals. Int J Health Geogr. 2006;5:39. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-5-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson RE, Wallis AB, O'Campo PJ, Schafer P. Neighborhood mapping and evaluation: a methodology for participatory community health initiatives. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:373–83. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croner CM, Sperling J, Broome FR. Geographic information systems (GIS): new perspectives in understanding human health and environmental relationships. Stat Med. 1996;15:1961–77. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19960930)15:18<1961::aid-sim408>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen D, Spear S, Scribner R, Kissinger P, Mason K, Wildgen J. “Broken windows” and the risk of gonorrhea. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:230–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLafferty S, Grady S. Immigration and geographic access to prenatal clinics in Brooklyn, NY: a geographic information systems analysis. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:638–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.033985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi M, Afzal B, Sattler B. Geographic information systems: a new tool for environmental health assessments. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23:381–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riner ME, Cunningham C, Johnson A. Public health education and practice using geographic information system technology. Public Health Nurs. 2004;21:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2004.21108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fast Forward, Inc. Sperling's best places: San Bernardino, California 92411. 2009. [cited 2010 Nov 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.bestplaces.net.

- 10.City of San Bernardino Police Department. Arrest statistics in San Bernardino. 2007. [cited 2008 Sep 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.ci.san-bernardino.ca.us/depts/police_department/default.asp.

- 11.Environmental Systems Resource Institute. 2009. ArcView: Version 9.2. Redlands (CA): Environmental Systems Resource Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12. ABC Act, Ch. 5, Art. 1, §23789 (Calif.)

- 13.Jamison B, Gaede D, Mataya R, Belliard JC. Reflections on public health and service-learning. Acad Exchange Q. 2008;12:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metzler MM, Higgins DL, Beeker CG, Freudenberg N, Lantz PM, Senturia KD, et al. Addressing urban health in Detroit, New York City, and Seattle through community-based participatory research partnerships. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:803–11. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]