Abstract

Retinoid-related receptor α (RORα) is an orphan nuclear receptor that constitutively activates transcription from its cognate response element. We show that RORα is Ca2+responsive, and a Ca2+/calmodulin-independent form of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (CaMKIV) potentiates RORα-dependent transcription 20- to 30-fold. Other orphan receptors including RORα2, RORγ and COUP-TFI are also potentiated by CaMKIV. Transcriptional activation by CaMKIV is orphan receptor selective and does not occur with either the thyroid hormone or estrogen receptor. CaMKIV does not phosphorylate RORα or its ligand-binding domain (LBD) in vitro, although the LBD is essential for transactivation. Therefore, the RORα LBD was used in the mammalian two-hybrid assay to identify a single class of small peptide molecules containing LXXLL motifs that interacted with greater affinity in the presence of CaMKIV. This class of peptides antagonized activation of orphan receptor-mediated transcription by CaMKIV. These studies demonstrate a pivotal role for CaMKIV in the regulation of orphan receptor-mediated transcription.

Keywords: Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase IV/calcium/orphan receptor/LXXLL/RORα

Introduction

Elevation of intracellular Ca2+ plays a prominent role in a broad array of cellular functions including the activation of transcription and regulation of cellular processes such as the cell cycle and apoptosis (Means, 1995). The Ca2+ signal is mediated principally by calmodulin (CaM), which serves as the cell's primary Ca2+ receptor in both the cytoplasm and nucleus. Ca2+/CaM activates many enzymes including protein kinases and phosphatases, adenylyl cyclases and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (Means, 1995). Within this group of signaling molecules, significant emphasis has been placed upon the CaM-dependent protein kinases (CaMKs). Three CaMKs, I, II and IV (CaMKI, CaMKII and CaMKIV, respectively), are multifunctional protein Ser/Thr kinases, each of which phosphorylate a variety of substrates in vitro and in vivo (for a review, see Anderson and Kane, 1998). While CaMKI and CaMKII are widely expressed throughout the body, CaMKIV expression is relatively limited to the brain, T-lymphocytes and post-meiotic male germ cells (Ohmstede et al., 1989; Frangakis et al., 1991; Means et al., 1991). CaMKIV is localized predominantly to the nucleus and becomes activated very rapidly upon the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ (Jensen et al., 1991). Activation of CaMKIV requires: (i) binding of Ca2+/CaM; (ii) phosphorylation of Thr200 in the ‘activation loop’ by an upstream activating kinase (CaMKK) that is also Ca2+/CaM-dependent; and (iii) autophosphorylation of serine residues present in the extreme N-terminus required for relief of a novel form of autoinhibition (Chatila et al., 1996). Truncation of the C-terminal CaM-binding and autoinhibitory domains of CaMKIV results in a Ca2+/CaM-independent enzyme whose activity still requires phosphorylation of Thr200 by a CaMKK (Chatila et al., 1996). CaMKIV is a potent activator of several transcription factors including CREB, ATF-1 and SRF (Miranti et al., 1995; Tokumitsu et al., 1995; Sun et al., 1996). CaMKIV-dependent activation of CREB-mediated transcription can occur through its ability to phosphorylate CREB on Ser133 (Matthews et al., 1994). However, CaMKIV may also play another role in CREB-mediated transcription through the activation of the CREB-binding protein (CBP) (Chawla et al., 1998), although the specific mechanism remains to be elucidated.

Our laboratory has evaluated potential roles of CaMKIV through the production of transgenic mice that express a kinase-inactive form of CaMKIV in T-lymphocytes (Anderson et al., 1997) as well as by elimination of the CaMKIV gene locus via homologous recombination (A.R.Means, unpublished data). Analysis of these animals revealed striking phenotypic consequences in neurological, lymphoid and reproductive tissues, correlating with the expression patterns of CaMKIV. Interestingly, the phenotypic consequences of the CaMKIV-deficient animals were similar to those of the staggerer mouse. The staggerer mouse represents a spontaneously arising mutation that has been studied as an animal model of ataxia (Sidman et al., 1962). In addition to the neurological defects, these animals also display immunological and reproductive deficiencies (Trenkner and Hoffmann, 1986; Guastavino and Larsson, 1992). Hamilton et al. (1996) positionally cloned the staggerer mutation and demonstrated that it prevents translation of the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of the retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor α (RORα). RORα is a member of the thyroid/steroid superfamily of nuclear receptors and is expressed in the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum as well as in lymphoid and reproductive tissues (Giguère et al., 1994; Hamilton et al., 1996; Steinmayr et al., 1998). RORα binds DNA as a monomer and has been shown to drive transcription constitutively from its cognate response element (Giguère et al., 1994, 1995). As this transactivation occurs in the absence of any known ligand, RORα is classified as an orphan receptor. Recently, two independent laboratory groups have disrupted the RORα gene and recapitulated the staggerer phenotype in both sets of mice, demonstrating that functional disruption of the RORα gene is the bona fide target of the staggerer mutation (Dussault et al., 1998; Steinmayr et al., 1998).

Given the ability of CaMKIV to activate transcription factors such as CREB, the overlapping tissue expression patterns of CaMKIV and RORα and the similar phenotypes of the CaMKIV- and RORα-deficient animal models, we tested the ability of CaMKIV to potentiate the transcriptional activity of RORα. We report here that RORα is a Ca2+-responsive transcription factor and that RORα, as well as several other orphan receptors, can be activated potently by CaMKIV. Transactivation of RORα is dependent upon its LBD, although the receptor itself is not the target of the kinase. We have identified a class of peptides containing an LXXLL motif that specifically interacts with the LBD of RORα in a CaMKIV-dependent manner. These peptides can serve as potent antagonists of RORα- and other orphan receptor-mediated transcription in both the absence and presence of CaMKIV. Our findings suggest a novel paradigm governing the transactivation of a select group of orphan receptors, in which biological stimuli that mobilize Ca2+ signaling cascades can markedly increase orphan receptor-mediated transcription via the activation of CaMKIV. Such a mechanism provides an alternative means by which these orphan receptors, when co-expressed in cells with CaMKIV, may drive transcription in the apparent absence of any cognate ligands.

Results

RORα is activated by CaMKIV and is a Ca2+–responsive transcription factor

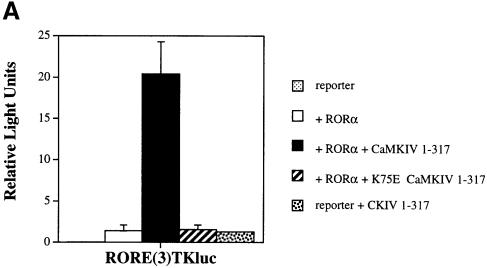

Based upon the similarity of phenotypes seen in staggerer and CaMKIV-deficient animals, we asked whether CaMKIV could increase transcription mediated by RORα. Thus, we transiently transfected the human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT with an expression vector for human RORα and its cognate luciferase-based reporter containing three copies of a consensus RORα response element in front of the thymidine kinase minimal promoter [RORE(3)TKluc]. As reported previously for this receptor, RORα displays constitutive and ligand-independent transcriptional activity (Figure 1A, open bar) (Giguère et al., 1994).

Fig. 1. Transcriptional activation of RORα by CaMKIV. (A) HaCaT cells were transfected with 4 μg of RORE(3)TKluc reporter and 1 μg of RORα expression vector in either the absence or presence of 4 μg of the Ca2+/CaM-independent (CaMKIV 1–317) or catalytically inactive (K75E CaMKIV 1–317) CaMKIV expression vectors. Cells were harvested after 36 h in culture and luciferase activity is reported as corrected relative light units. (B) Ca2+influx mediated by ionomycin treatment induces RORα transcriptional activity. HaCaT cells were transfected with reporter and RORα expression vector and after 16 h in culture were treated with 0.67 μM ionomcyin, 30 μM KN-93 or both ionomycin and KN-93. Cells were stimulated for an additional 24 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as corrected relative light units.

To determine if CaMKIV could potentiate this activity further, an expression vector encoding Ca2+/CaM-independent CaMKIV (CaMKIV 1–317) was co-transfected with the RORα expression vector. Quite surprisingly, CaMKIV activated transcription from RORE(3)TKluc an additional 20- to 30-fold over the activity of RORα alone (Figure 1A, black bar). Co-transfection of a catalytically inactive expression vector of CaMKIV (K75E CaMKIV 1–317) failed to produce any additional activation above that of RORα's constitutive activity, indicating that CaMKIV protein kinase activity was required for RORα activation (Figure 1A, striped bar) while co-transfection of CaMKIV 1–317 modestly activated reporter alone (Figure 1A, speckled bar). Because the RORα expression vector used in these experiments was driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, and because this promoter has recently been shown to be Ca2+ sensitive, we produced constructs derived from the Ca2+-insensitive Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) and SV40 promoters and compared them with CMV-driven RORα in the absence and presence of CaMKIV 1–317. Each RORα expression vector displayed statistically indistinguishable constitutive activity and each was significantly induced by CaMKIV 1–317 (data not shown), suggesting that the activation of transcription is not due to an indirect effect of the kinase on the RORα expression vector. Finally, CaMKIV-dependent activation of RORα was also found to occur in other cell lines including the human T-cell line Jurkat and the rat pituitary cell line GH3 (data not shown). In each instance, marked activation of RORα occurred in the presence of Ca2+/CaM-independent CaMKIV, indicating that this effect was not cell line specific.

While it was clear that RORα could be activated by Ca2+/CaM-independent CaMKIV, we wanted to determine if RORα activity could be modulated by Ca2+signaling. Therefore, HaCaT cells were transfected with RORα and subsequently were stimulated with the Ca2+-elevating agent ionomycin. Ionomycin treatment had a negligible effect upon reporter alone (Figure 1B, left hand side). However, treatment with ionomycin potently activated RORα. This activation resulted in nearly a 12-fold activation of RORα in the presence of Ca2+versus its activity in the presence of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (Figure 1B, right hand side, open versus stippled bar).

HaCaT cells express endogenous CaMKIV based upon their expression of CaMKIV mRNA as detected via RT–PCR and Northern analysis (C.D.Kane and A.R.Means, unpublished data). In addition to CaMKIV, it is possible that the ubiquitously expressed CaM kinases I and II as well as other CaM-dependent enzymes are also expressed in these cells. In order to identify a role for a CaM kinase in RORα activation, KN-93, a selective inhibitor of CaMKI, II and IV, was added concomitantly with iono– mycin to cells transfected with RORα. While KN-93 did not adversely effect the constitutive activity of RORα (Figure 1B, black bar), the drug potently repressed the ability of ionomycin to activate RORα (Figure 1B, striped bar). These results show that a CaM kinase inhibitor can block Ca2+-dependent activation of RORα, suggesting that activation of RORα-mediated transcription by Ca2+is occurring via activation of a CaM kinase.

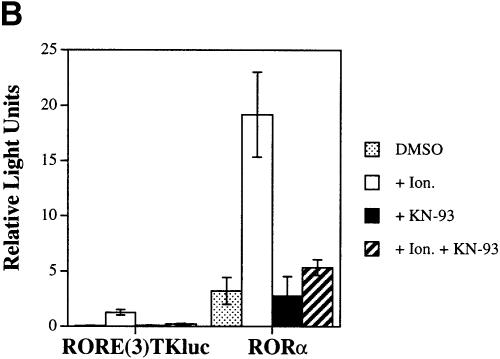

CaMKIV and I, but not II, can activate RORα

In order to determine which members of the CaM kinase family could activate RORα transcription, HaCaT cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors encoding Ca2+/CaM-independent CaM kinase I, II or IV. As previously seen in Figure 1, CaMKIV potently activated RORα-mediated transcription 20- to 30-fold more than that seen by RORα alone (Figure 2, black versus open bar). Activation was also obtained with Ca2+/CaM-independent CaMKI (Figure 2, shaded bar). The different efficacies of RORα activation in response to CaMKIV and CaMKI may reflect differences in the relative expression levels of the transfected kinase cDNA constructs in HaCaT cells. In contrast, Ca2+/CaM-independent CaMKIIα failed to demonstrate any activation and actually seemed to repress RORα's constitutive activity (Figure 2, wavy bar). Indeed, in contrast to CaMKIV and CaMKI, CaMKII has been shown potently to repress transcriptional activation by several transcription factors (Matthews et al., 1994; Nghiem et al., 1994; S.S.Hook, C.D.Kane and A.R.Means, unpublished observations). Catalytically inactive mutants of CaMKIV and CaMKIIα (K75E CaMKIV 1–317 and K42M CaMKIIα 1–290) failed to activate RORα (Figure 2, lateral and vertical striped bars, respectively). These results demonstrate a clear CaM kinase specificity for RORα activation, with CaMKIV and CaMKI acting to stimulate RORα-mediated transcription while CaMKIIα fails to do so.

Fig. 2. Calmodulin kinase specificity for activation of RORα-mediated transcription. HaCaT cells were transfected with reporter and 1 μg of RORα expression vector in either the absence or presence of 4 μg of each CaM kinase expression vector. The kinases included Ca2+/CaM-independent CaMKIV (CaMKIV 1–317), catalytically inactive CaMKIV (K75E CaMKIV 1–317), Ca2+/CaM-independent CaMKI (CaMKI 1–294), Ca2+/CaM-independent CaMKIIα (CaMKIIα 1–290) and catalytically inactive CaMKIIα (K42M CaMKIIα 1–290). Cells were maintained in culture for 36 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as corrected relative light units.

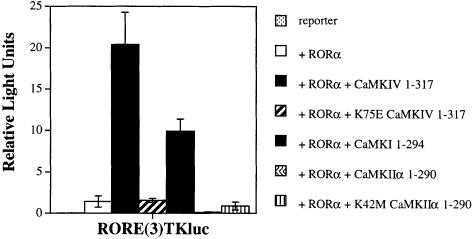

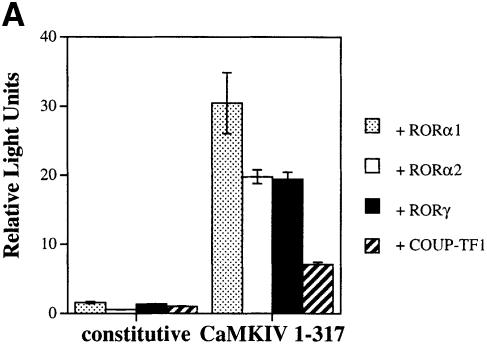

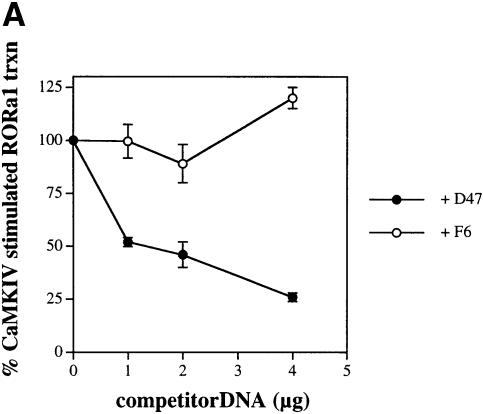

Activation of transcription by CaMKIV is selective for orphan nuclear receptors

Next we examined if activation of RORα-mediated transcription was specific for RORα or was a property shared by several classes of nuclear receptors. We therefore surveyed a cohort of nuclear receptors for their ability to be activated by CaMKIV. Several different orphan receptors were transiently transfected into HaCaT cells in the absence or presence of CaMKIV 1–317. The RORE(3)TKluc reporter was used for each of these receptors as they have all been shown previously to support transcription from this reporter (Giguère et al., 1994; Schräder et al., 1996). In addition to RORα1, the receptors tested included an N-terminal splice variant of RORα1 termed RORα2, a separate ROR gene family member termed RORγ and an unrelated orphan receptor COUP-TFI. As seen in Figure 3A (left hand side), all of these receptors display some ligand-independent, constitutive activity, as has been reported previously (Giguère et al., 1994; Medvedev et al., 1996; Schräder et al., 1996). Co-transfection of CaMKIV 1–317 resulted in marked activation of all the orphan receptors tested (Figure 3A, right hand side). The fold activation for the ROR orphan receptors was generally in the range of 20- to 40-fold induction, while that for COUP-TF1 was in the 7- to 10-fold range.

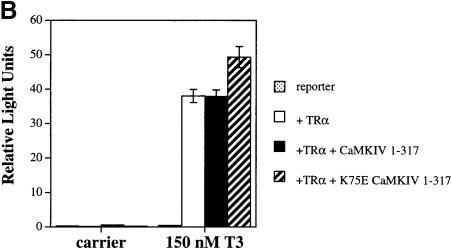

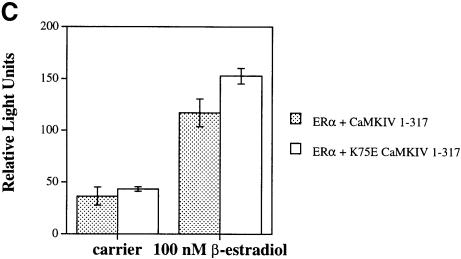

Fig. 3. Orphan receptor specificity for transcriptional activation by CaMKIV. (A) HaCaT cells were transfected with 4 μg of RORE(3)TKluc reporter and 1 μg of the appropriate orphan receptor expression vector in both the absence and presence of 4 μg of CaMKIV 1–317 expression vector. Cells were maintained in culture for 36 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as corrected relative light units. (B) Jurkat cells were transfected with 12 μg of TREpal(2)luc reporter and 4 μg of TRα expression vector in the absence or presence of 4 μg of either CaMKIV 1–317 or K75E CaMKIV 1–317. Cells were treated with 150 nM T3 for 36 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as corrected relative light units. (C) HepG2 cells were transfected with 1.5 μg of ERETKluc and 1 μg of ERα expression vector in the presence of 4 μg of either CaMKIV 1–317 or K75E CaMKIV 1–317. Cells were treated with 100 nM 17β-estradiol for 24 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as corrected relative light units.

Next we tested the ability of CaMKIV to potentiate the activity of two prototypical nuclear receptors, the thyroid hormone receptor (TRα) and the estrogen receptor (ERα). Transient transfection of Jurkat cells with an expression vector for TRα and treatment with 150 nM T3 resulted in a large T3-dependent induction of TRα-mediated transcription (Figure 3B, open bars). If CaMKIV 1–317 was co-transfected with TRα, no potentiation of TRα-mediated transcription occurred in either the absence or the presence of T3 (Figure 3B, black bars). Likewise, co-transfection with K75E CaMKIV 1–317 also had no significant effects upon TRα-mediated transcription (Figure 3B, striped bars)

Similar experiments were performed using ERα to test for transcriptional potentiation in the presence of CaMKIV. As seen in Figure 3C (left side), the presence of CaMKIV 1–317 did not potentiate the ligand-independent activity of ERα. CaMKIV also failed to provide any additional potentiation of the 17β-estradiol-dependent activity of ERα (Figure 3C, right side). These findings demonstrate that the presence of CaMKIV does not change either the ligand-dependent or ligand-independent transactivation of the thyroid or estrogen nuclear receptors and that the ability of CaMKIV to activate transcription seems to be limited to a distinct group of orphan receptors.

Phosphorylation of the N-terminus of RORα is not required for CaMKIV-dependent transactivation

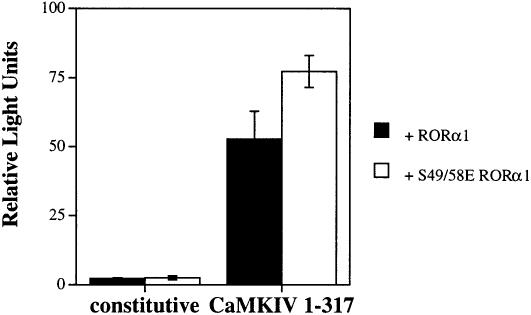

Previous studies by Giguère et al. (1994, 1995; McBroom et al., 1995) demonstrated a regulatory region within the RORα N-terminal domain that influences the specificity and efficiency of binding to DNA. In addition, this domain contains several putative phosphorylation sites for multiple protein kinases. Two sites, Ser49 and Ser58, are found within this regulatory domain and match the consensus recognition motifs for CaMKIV (Giguère et al., 1995; White et al., 1998). In order to test if these residues are required for CaMKIV-dependent activation of RORα, a double point mutant, S49E/S58E RORα (S49/58E RORα), was used in the transient transfection assay. As shown in Figure 4 (left hand side), both the wild-type and S49/58E RORα have identical constitutive activities on the reporter. Co-transfection of CaMKIV 1–317 resulted in potent activation of both receptors (Figure 4, right hand side). The overall transcriptional activity of S49/58E RORα was slightly greater than that of the wild-type receptor in the CaMKIV-activated state. However, the overall fold induction of both wild-type and S49/58E RORα by CaMKIV was similar (23-fold versus 30-fold, respectively). This observation was corroborated by an additional experiment in which an N-terminal truncation mutant (Δ23–74 RORα) also displayed robust activation after co-transfection with CaMKIV (data not shown). These experiments suggest that the putative CaMKIV phos– phorylation sites found within the N-terminal domain of RORα are not required for the CaMKIV-dependent activation of RORα-mediated transcription.

Fig. 4. Transcriptional activation of wild-type or S49/58E RORα by CaMKIV. HaCaT cells were transfected with reporter and 1 μg of wild-type or S49/58 RORα in the absence or presence of 4 μg of CaMKIV 1–317. Cells were maintained in culture for 36 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as corrected relative light units.

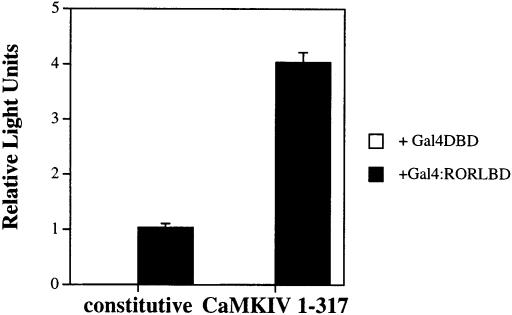

Enhancement of RORα-dependent transactivation by CaMKIV is mediated through the LBD

While there is significant variability in the primary amino acid sequences of the LBDs of the various members of the nuclear/steroid receptor superfamily, crystallographic analysis of these domains from PR, ERα, PPARγ, RXRα and TRα have shown that the principal folding features are conserved (Wurtz et al., 1996). Structural and mutagenesis studies of liganded receptors have suggested a key role for the activation function 2 (AF-2) domain, a conserved region within the LBD structure corresponding to helix 12 that forms an interface with members of the coactivator class of nuclear receptor-interacting proteins such as SRC1, GRIP1 and pCIP (Oñate et al., 1995; Hong et al., 1996; Wurtz et al., 1996; Torchia et al., 1997). Deletion analysis of RORα demonstrates that this receptor has a functional AF-2 domain within its LBD. Removal of this domain renders RORα transcriptionally inactive and results in the staggerer phenotype (McBroom et al., 1995; Hamilton et al., 1996; Harding et al., 1997). In order to address if the LBD of RORα is sufficient to mediate CaMKIV-dependent activation of transcription, the LBD of RORα was fused in-frame to the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of the yeast transcription factor Gal4 (Gal4:RORLBD). This construct or Gal4DBD alone was co-transfected into GH3 cells with a 5× Gal4UAS/TATA/luciferase reporter in the absence or presence of CaMKIV 1–317. As seen in Figure 5, Gal4:RORLBD exhibits constitutive transcriptional activity and can be activated upon co-transfection with CaMKIV, while the Gal4DBD is transcriptionally silent under all conditions tested. These results demonstrate that the effects of CaMKIV on full-length RORα can be recapitulated with an RORLBD chimera. Thus, the LBD of RORα is sufficient for mediating the CaMKIV-dependent activation of transcription.

Fig. 5. Transcriptional activation of a Gal4:RORLBD chimera. GH3 cells were transfected with 3 μg of 5× Gal4UAS/TATA/luciferase reporter and 2 μg of Gal4DBD or Gal4:RORLBD in the absence or presence of 4 μg of CaMKIV 1–317. Cells were maintained in culture for 36 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as corrected relative light units.

The ligand-binding domain of RORα is not phosphorylated

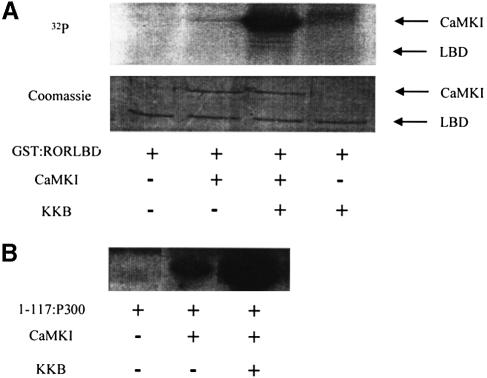

As the LBD of RORα is capable of being potentiated by co-transfection with CaMKIV, we wanted to determine if the LBD of RORα is a direct target for phosphorylation by CaMKIV. Therefore, the entire LBD of RORα (amino acids 270–524) was expressed as a GST fusion protein in Escherichia coli (GST:RORLBD), purified to homogeneity and used as a substrate for an in vitro kinase assay. Given the overlapping substrate specificity of CaMKI and IV, as well as the ability of each of these kinases to activate RORα in transient transfections and the fact that the kinetics of peptide substrate phosphorylation are greater for CaMKI than they are for CaMKIV, CaMKI was chosen for the in vitro phosphorylation reaction.

As shown by the autoradiogram in Figure 6A (upper panel), GST:RORLBD was not phosphorylated in the presence of either kinase reaction buffer or CaMKI. CaMKI can be activated further by the addition of CaMKKB, which phosphorylates Thr177 of CaMKI. This activation loop phosphorylation significantly enhances the kinetics of CaMKI substrate phosphorylation and increases its specific activity 25-fold (Haribabu et al., 1995). The addition of CaMKKB to CaMKI resulted in the phos– phorylation of CaMKI, yet CaMKI failed to recognize GST:RORLBD as a substrate (Figure 6A, upper panel). Likewise, CaMKKB alone also failed to phosphorylate GST:RORLBD. Both enzymes were shown to be active, as control reactions run in parallel with a peptide corresponding to the N-terminal 1–117 amino acids of P300 (1–117:P300) demonstrated that CaMKI was active on its own and that addition of CaMKKB resulted in a marked increase in CaMKI activity (Figure 6B). Coomassie staining of the fractionated kinase reactions indicated that GST:RORLBD was present in equal amounts for all reaction conditions (Figure 6A, bottom panel). These results demonstrate that the LBD of RORα is not an in vitro substrate for CaMKI and suggest that the mechanism of CaM kinase activation of RORα is not via direct phosphorylation of RORα itself. This is supported by the failure of either CaMKI or CaMKIV to phosphorylate in vitro transcribed and translated full-length RORα (data not shown).

Fig. 6. In vitro phosphorylation of GST:RORLBD. (A) The ligand-binding domain of RORα was used as a substrate for in vitro kinase assay using recombinant CaMKI and KKB. All recombinant proteins were expressed and purified as fusion proteins with either GST (RORLBD and CaMKI) or maltose-binding protein (KKB). Upper panel: an autoradiogram of kinase reactions after fractionation on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. GST:RORLBD (500 ng) was incubated in the absence (–) or presence (+) of CaMKI (200 ng) or KKB (500 ng) in kinase reaction buffer for 20 min. The positions of CaMKI and GST:RORLBD are denoted by arrows. CaMKI does not undergo autophosphorylation but will become phosphorylated in the presence of KKB. Lower panel: Coomassie staining of the gel used for autoradiography. Arrows to the right denote the position of CaMKI and GST:RORLBD. (B) His-tagged 1–117:P300 serves as a positive control for CaMKI activity. Kinase assays were performed as described in (A) using 1–117:P300 (500 ng) as a substrate. The panel displays an autoradiogram of kinase reactions after fractionation on SDS–PAGE. Coomassie staining indicated that the peptide was present in equal amounts for all reactions (data not shown).

Detection of RORLBD-interacting peptides

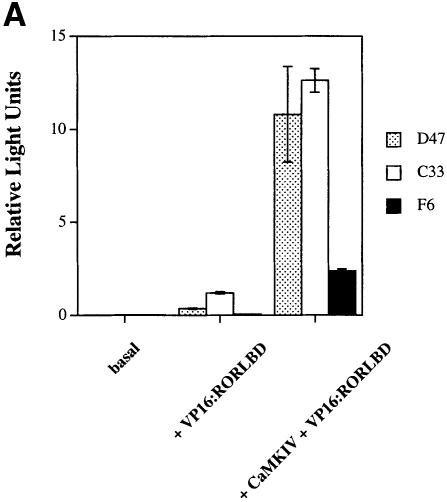

The nuclear receptor coactivators have been found to contain a signature LXXLL motif, also referred to as an ‘NR-box’ (Heery et al., 1997; Torchia et al., 1997). In an attempt to identify LXXLL-containing peptides that specifically interact with liganded ERα, Chang et al. (1999) used a combinatorial phage display approach and discovered three classes (class I, II and III) of small, 19 amino acid peptides that specifically bound ERα in an agonist-dependent manner. Representative members of each of these classes as well as LXXLL-containing peptides from the coactivators P300, GRIP1 and SRC1 were tested in the context of the mammalian two-hybrid assay in order to identify peptides that could interact with the LBD of RORα in either the absence or presence of CaMKIV. A series of peptides containing a central LXXLL motif were expressed as fusion proteins with the Gal4DBD. The entire RORα LBD was expressed as a fusion protein with the VP16 activation domain (VP16:RORLBD) and these two plasmids were transiently transfected into HaCaT cells in the absence or presence of CaMKIV 1–317. A single class of VP16:RORLBD-interacting peptides was identified. As seen in Figure 7A (left hand side), the peptides fused to Gal4DBD did not support basal transcription by themselves. When co-transfected in the presence of VP16:RORLBD, two members of the class II peptides showed weak interaction (Figure 7A, D47 and C33, middle section). Surprisingly, co-transfection of CaMKIV 1–317 resulted in a robust increase in the interaction between class II peptides D47/C33 and VP16:RORLBD that was not seen with the non-interacting class III peptide F6 (Figure 7A, right hand side). The class II peptides D47 and C33 were the only fusion proteins that displayed basal and CaMKIV-dependent interaction. Other peptides containing LXXLL motifs from P300, GRIP-1 and SRC1 failed to interact with the RORLBD in either the absence or presence of CaMKIV (data not shown). These results suggest that the LBD of RORα is necessary and sufficient for interaction with peptides containing the LXXLL nuclear receptor-interacting motif and that CaMKIV can increase these interactions in the context of a mammalian cell.

Fig. 7. Mammalian two-hybrid assay using LXXLL-containing peptides and CaMKIV 1–317. (A) HaCaT cells were transfected with 3 μg of 5× Gal4UAS/TATA/luc with 2 μg of Gal4DBD fusion of the LXXLL-containing peptides D47, C33 and F6 either alone or in the presence of 2 μg of VP16:RORLBD or with both VP16:RORLBD and 4 μg of CaMKIV 1–317. Cells were maintained in culture for 36 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as corrected relative light units. (B) Transfections were performed as in (A) using 2 μg of VP16:ERαHBD. Cells were maintained in phenol red-free MEMα with 10% charcoal-stripped FBS at all times. Approximately 16 h after transfection, cells were treated with 100 nM β-estradiol or ethanol for 24 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as corrected relative light units.

In order to strengthen the correlation between CaMKIV activity and the modulation of orphan receptor activity, we assessed the peptide-binding activities of ERα in the context of the mammalian two-hybrid assay in the absence or presence of CaMKIV. Recalling that ERα is unresponsive to CaMKIV (Figure 3C), we obtained an expression vector containing the VP16 activation domain fused to the entire hormone-binding domain (HBD) of ERα (VP16:ERαHBD). Chang et al. (1999) have shown that the peptide-binding specificity of ERα is the converse of what is observed for RORα, i.e. β-estradiol-bound VP16:ERαHBD binds weakly to D47 and strongly to F6. This result is recapitulated in Figure 7B (left hand side) in which agonist-bound VP16:ERαHBD interacts weakly with D47 and strongly with F6, whereas no interactions occur in the absence of ligand. Co-transfection with CaMKIV 1–317 fails to increase the interactions between VP16:ERαHBD and D47, while causing a modest (<1-fold) increase of interaction for F6 (Figure 7B, right hand side). The failure of CaMKIV to cause a significant increase in the interaction between the peptides and the HBD of ERα is consistent with the selectivity seen for the activation of distinct classes of nuclear receptors by CaMKIV.

Class II LXXLL-containing peptides can disrupt RORα-mediated transcription

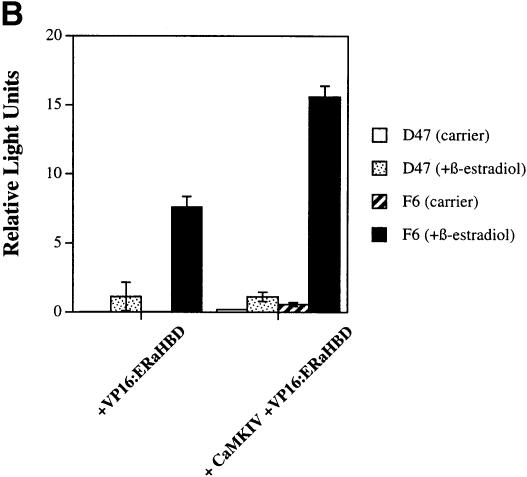

It has been suggested that LXXLL-containing peptides interact with the AF-2 region of nuclear receptors by mimicking interactions used by full-length coactivators (Heery et al., 1997; Torchia et al., 1997; Nolte et al., 1998; Chang et al., 1999). Based on these data, we thought it likely that the class II peptides should also interact with the AF-2 region of RORα and that, if so, they should act as dominant-negative inhibitors of RORα-mediated transcription. In order to investigate this hypothesis, RORα was co-transfected with CaMKIV 1–317 in HaCaT cells in the presence of increasing input DNA encoding either the RORα-interacting peptide D47 or the non-interacting peptide F6. Luciferase activity was plotted as the percentage of maximal RORα-dependent activity seen in the presence of CaMKIV. As seen in Figure 8A, D47 was a potent inhibitor of CaMKIV-dependent, RORα-mediated transcription, while the non-interacting peptide F6 had no effect (filled versus open circles, respectively). Similar results were obtained using D47 and F6 in the absence of CaMKIV. Constitutive RORα transcription was suppressed in the presence of D47, while F6 had no effect (data not shown). Repression of RORα-mediated transcription was only observed with the VP16:RORLBD-interacting peptide D47, suggesting that this protein may be preventing the interaction of RORα with a putative endogenous coactivator.

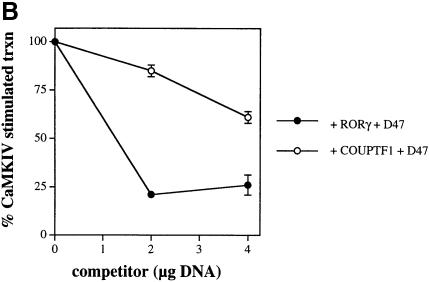

Fig. 8. Certain LXXLL-containing peptides antagonize RORα-mediated transcription. (A) HaCaT cells were transfected with 4 μg of RORE(3)TKluc reporter, 1 μg of RORα and 4 μg of CaMKIV 1–317 in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of either D47 or F6 competitor DNA. Cells were maintained in culture for 36 h, harvested and the luciferase activity reported as a percentage of the maximal, CaMKIV-dependent luciferase activity that occurs when competitor is absent. (B) Transfections were performed and analyzed as in (A), except using 1 μg of RORγ or COUP-TF1 in the presence of increasing concentrations of D47 competitor DNA.

In order to observe if D47-dependent repression of RORα was unique to this receptor or if it was common to other orphan receptors, a similar repression experiment was carried out with the orphan nuclear receptors RORγ and COUP-TFI. As seen in Figure 8B, D47 was a potent inhibitor of CaMKIV-dependent RORγ-mediated transcription and also repressed COUP-TFI, but to a lesser extent (filled versus open circles). While RORγ was repressed to ∼25% of its maximal activity and to an extent similar to RORα, COUP-TFI was repressed to only 60% of its maximal activity. This may be due to the fact that on the RORE(3)TKluc reporter, RORα and RORγ bind as monomers and may be repressed efficiently by a single copy of D47. In contrast, COUP-TFI will bind as either a homodimer or a heterodimer with RXR (Cooney et al., 1992) and, therefore, may not be repressed as efficiently by a single copy of D47. Collectively, these results suggest that the ability of D47 to repress RORα, RORγ and COUP-TFI is a common property, and imply that D47 is competing for a specific coactivator that is present in HaCaT cells and required for the transcriptional activity of these orphan receptors.

Discussion

The term orphan receptor has been developed to describe those nuclear receptors for which there are no known ligands. Unlike the traditional thyroid/steroid class of nuclear receptors that require specific ligands to support transcription, the orphan receptors display constitutive activity that is thought to be ligand independent. Our experiments have indicated that an established signaling pathway can potently activate orphan receptor-mediated transcription in a previously undescribed manner. We have shown that RORα is a Ca2+-responsive transcription factor whose constitutive activity is significantly enhanced by Ca2+influx and that this increase of activity requires CaM kinase activity. In this respect, RORα joins CREB as a facilitator of Ca2+-induced gene expression. Many biological stimuli including hormones, growth factors and T-cell receptor engagement induce Ca2+ signals and subsequent activation of transcription (Means, 1995). In those tissues that co-express RORα and CaMKIV, such stimuli would be predicted to be significant activators of RORE-responsive genes. The identification of RORE-containing genes in tissues expressing CaMKIV will be a prerequisite for testing this hypothesis in vivo.

Covalent modification via phosphorylation is known to be a potent mechanism for activation of transcription factors such as CREB and the CREB family members (Gonzalez and Montminy, 1989; Sun et al., 1996). In stimulated cells, CaMKIV and other CREB kinases are known to phosphorylate CREB on Ser133. This phos– phorylation event is required for the recruitment of the coactivator CBP, which nucleates a multiprotein complex that ultimately produces a large increase of CREBmediated transcription (Chrivia et al., 1993). Stimulation of nuclear hormone receptors occurs through the introduction and binding of their cognate ligands. Ligand binding dissociates bound co-repressor molecules, which allows recruitment of coactivator molecules that support transcription. Like CREB, several of the nuclear receptors including PR, ERα, ERβ and PPARγ undergo phosphorylation (for a review, see Weigel and Zhang, 1998). The receptors are often multiply phosphorylated on serine and threonine residues by several different kinases including PKA and the MAP kinases (Aronica and Katzenellenbogen, 1993; Bunone et al., 1996; Weigel and Zhang, 1998). In general, nuclear receptor phosphorylation affects DNA and/or ligand binding, resulting in either modest potentiation or repression of transcription (Aronica and Katzenellenbogen, 1993; Hu et al., 1996; Takimoto et al., 1996). Our studies indicate that the mechanism of RORα activation is unlikely to include the direct phosphorylation of RORα by CaMKIV. Mutation of potential CaMKIV phosphorylation sites does not prevent the ability of CaMKIV to activate RORα (Figure 4). Additionally, CaMKI will not phosphorylate the LBD of RORα in vitro (Figure 6A), further suggesting that the target of CaM kinase activity is not RORα itself.

The naturally occurring staggerer mutation and deletion analysis of RORα, as well as our own work (Figure 5), demonstrates that the AF-2 domain of the RORα LBD is required for transcriptional activity. In the context of the mammalian two-hybrid assay performed in HaCaT cells, the LBD of RORα is sufficient for interaction with specific LXXLL-containing peptides. Co-transfection of CaMKIV increases this interaction significantly, demonstrating that the LBD is a sufficient platform for supporting CaMKIV-dependent induction of transcription. Direct phosphorylation of the interacting LXXLL peptides by CaMKIV is not possible, as they do not contain the RXXS substrate recognition motif required for substrates of CaMKIV (Table I). This finding strongly suggests that CaMKIV is phosphorylating and activating another protein(s) that is serving as a bridge or scaffold between the LBD and the interacting class II peptides.

Table I. RORαLBD interaction motifs.

| Peptide name | Sequence | Interaction with RORαLBD |

|---|---|---|

| D47 | HVYQHPLLLSLLSSEHESG | yes |

| C33 | HVEMHPLLMGLLMESQWGA | yes |

| Consensus motif | HVXXHPLLØXLL | |

| F6 | GHEPLTLLERLLMDDKQAV | no |

| P300 | AASKHKQLSELLRSGSSPN | no |

| GRIP-1 (1) | DSKGQTKLLQLLTTKSDQM | |

| (2) | LKEKHKILHQLLQDSSSPV | |

| (3) | KKKENALLRYLLDKDDTKD | no |

| SRC-1 (1) | YSQTSHKLVKLLTTTAEQQ | |

| (2) | LTARHQILHRLLQEGSPSD | |

| (3) | ESKDHQLLRYLLDKDEKDL | no |

The RORαLBD interaction motif was generated after sequence analysis of the class II peptides. All amino acids are represented by their single letter codes, with Ø referring to L or M. Also shown are the sequences from previously described coactivator proteins that failed to interact with VP16:RORLBD as assessed via the mammalian two-hybrid assay.

Potential candidates for the ‘bridge’ between RORα and the class II RORα-interacting peptides are the co-integrator molecules CBP and/or P300, which act as transcriptional adaptors for a plethora of transcription factors (Chrivia et al., 1993; Eckner et al., 1994). The adenoviral oncoprotein E1A can bind to and inhibit CBP/P300 function (Arany et al., 1995). Therefore, cotransfection of an expression vector encoding E1A commonly is used to disrupt CBP/P300-dependent transcription. Indeed, co-transfection of E1A represses >95% of the CaMKIV-dependent activation of RORα, implicating CBP/P300 in RORα-mediated transcription (data not shown). However, in contrast to a recent report which described the interaction between the N-terminus of P300 and RORα in JEG-3 cells (Lau et al., 1999), mammalian two-hybrid analysis using the LXXLL domain of P300 (amino acids 74–92) or larger fragments of P300 (amino acids 1–117 or 1–595) failed to interact with VP16:RORLBD in HaCaT cells (Table I and data not shown). Clearly, in HaCaT cells, CBP/P300 is required for RORα function but associates with RORα indirectly, suggesting a supporting role for this co-integrator in RORα-mediated transcription.

Analysis of the class II peptides that interact with RORα's LBD has allowed the creation of an RORα interaction motif where the primary determinants appear to be HVXXHPLLØXLL (Table I). Note that the coactivators that failed to interact with RORα's LBD in HaCaT cells (P300, SRC-1 and GRIP1) do not contain a proline residue at the –2 position relative to the LXXLL sequence. The ability of the class II peptides to interact with RORα's LBD would imply that a proline at the –2 position is a key determinant of coactivator–orphan receptor binding specificity. Pattern Hit Initiated (PHI)-BLAST searches of the sequence database using this consensus and the peptide sequences of C33 and D47 reveal that there are currently no statistically significant identities between the peptides and the deposited sequences. This raises the exciting possibility that a novel, ‘class II-like’ coactivator molecule exists for the orphan receptors that has yet to be identified. Such a factor would be expected to be expressed in multiple tissues and to interact stably and constitutively with RORα, based upon the ability of RORα to drive transcription in the absence of CaMKIV in at least three different cell lineages (epidermal, lymphoid and neuronal; data not shown). There is current biological precedence for a nuclear receptor that is constitutively active in the absence of naturally occurring ligands. The orphan receptor CAR-β (constitutive androstane receptor-β) has been shown to exhibit ligand-independent transcription by virtue of the ability of its LBD to interact stably with the coactivator SRC-1 in the absence of exogenous hormone (Forman et al., 1999). CAR-β and RORα may be mechanistically similar with respect to their constitutive interaction with coactivator molecules and transcriptional activity in the absence of naturally occurring ligands.

Further evidence for the existence of a ‘class II-like’ coactivator is found in the ability of the D47 peptide to serve as an efficacious antagonist of orphan receptor-mediated transcription. Both RORα and RORγ, and to a lesser extent COUP-TFI, are repressed by co-transfection of D47. This broad spectrum inhibition would suggest that D47 may be competing with an endogenous coacti– vator found in HaCaT cells for orphan receptor binding. If so, this orphan receptor-specific coactivator could itself be a potential target for CaMKIV, in addition to that of the putative co-integrator molecule(s) that has been implicated in orphan receptor-mediated transcription as defined previously in the mammalian two-hybrid experiments. In addition, these studies suggest that the class II peptides could be used as peptide antagonists of orphan receptor-mediated transcription. As such, these peptides could be powerful tools in the study of orphan receptor-related biology or as possible therapeutic agents in cases of orphan receptor-mediated disease.

In recent years, the physiological ligands for several former orphan receptors have been discovered and found to be metabolites of lipophilic and/or steroid molecules. These include 9-cis retinoic acid for RXR (Heyman et al., 1992), polyunsaturated lipids and their metabolites for PPARs (Göttlicher et al., 1992), and, most recently, chenodeoxycholic acid and other bile acids for the farnesyl X receptor (Makishima et al., 1999; Parks et al., 1999). It remains probable that several of the current orphan receptors will eventually be shown to require ligands in order to stimulate transcription. In this regard, an alterna– tive explanation concerning the ability of CaMKIV to activate RORα that has not been addressed in our studies is the possibility that activation of CaMKIV results in creation of the physiological ligand of RORα. Such a process could be due to the ability of CaMKIV to covalently modify and therefore regulate the activity of a biosynthetic enzyme involved in either the production or destruction of a currently unidentified, naturally occurring ligand for the orphan receptors examined here. Confirmation of these ideas awaits the time that this currently hypothetical ligand has been isolated and fully characterized as a bona fide ligand of RORα. Based upon this work, we can propose at least two possible models for activation of RORα-mediated transcription by CaMKIV. In the first model, CaMKIV mediates its positive effects on transcription through the covalent modification of coactivator molecules such as the putative ‘class II-like’ coactivator and/or CBP/P300. The second model of CaMKIV activation could occur at the level of the LBD of RORα in a manner reminiscent of the traditional nuclear receptors. In this scenario, cellular stimulation and CaMKIV activation would modulate the activity of a biosynthetic enzyme which modifies or produces a lipophilic molecule that serves as a physiological ligand of RORα. Ligand binding to RORα would nucleate a complex between the receptor, the ‘class II-like coactivator’ and a co-integrator molecule such as CBP/P300, as is seen with the thyroid/steroid class of nuclear receptors. It should be noted that these models describing the CaMKIV-dependent activation of RORα and the other orphan receptors are not mutually exclusive and could easily utilize components of each of the postulated mechanisms in order to achieve maximal receptor activation. In an effort to delineate which of these pathways are at work in response to CaMKIV activation, we are currently in the process of identifying and characterizing the molecular mechanism by which CaMKIV mediates orphan receptor-dependent transcription.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

Expression vectors in the CMX background containing the cDNAs for RORα (RORα1), Δ23–74 RORα, RORα2, RORγ, as well as the reporter RORE(3)TKluc have been described previously and were kindly provided by V.Giguère (Giguère et al., 1994, 1995; Medvedev et al., 1996). The site-specific mutant S49/58E RORα was generated via the Kunkel method of mutagenesis using a synthetic oligonucleotide containing the mutations of interest and was confirmed by sequencing. RSV-COUP-TF1 (a gift of A.Cooney) and RSV:TRα, TREpal(2)luc, RSV:ERα and ERE(1)TKluc were provided by D.McDonnell. The Ca2+/CaM-independent and catalytically inactive expression vectors of pSG5:CaMKIV 1–317, pSG5:CaMKIIα 1–290 and SRα:CaMKI 1–294 have also been described previously (Sun et al., 1995; Chatila et al., 1996; Anderson et al., 1998). The His-tagged 1–117:P300 plasmid was created via PCR amplification of the N-terminus of human P300 (amino acids 1–117), and the subsequent product was subcloned into the prokaryotic expression vector pet30(c) (Novagen). The plasmid GST:RORLBD was generated by amplifying the LBD (amino acids 270–524) of CMX:RORα with Pfu polymerase and subcloning the product into the GST expression vector pGEXKG. Gal4:RORLBD and VP16:RORLBD were created by subcloning the LBD of GST:RORLBD into the EcoRI–BamHI sites of either the Gal4DBD (pM) plasmid or the VP16 activation domain plasmid of the mammalian two-hybrid system (Clontech). The 19 amino acid LXXLL-containing domain of human P300 (amino acids 74–92) was amplified using similar procedures and subcloned into the SalI–BamHI sites of pM. Plasmids pM:D47, pM:C33, pM:F6, pM:SRC1 (amino acids 629–769), pM:GRIP1 (amino acids 634–760) and VP16:ERαHBD were provided by D.McDonnell and have been described previously (Chang et al., 1999). All PCR products were sequenced to verify their nucleotide sequences.

Transfections

HaCaT cells were transiently transfected using the DEAE–dextran method. Cells were plated at a density of 250 000 cells/well (6-well plates) in 90% minimal essential medium (MEMα) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco-BRL) in 1× penicillin/streptomycin and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 18–24 h. DNAs (see figures) and an additional 250 ng of RSV:LacZ (for transfection efficiency) were added to 1× Hank's buffered saline solution (HBSS) and DEAE–dextran (Sigma), mixed and added to twice washed cells (HBSS) overlaid with 100% MEMα with 100 μM choloroquine for 3 h. Afterwards, cells were glycerol shocked, washed and maintained in 90% MEMα/10% FBS for ∼36 h until harvest. Jurkat cells and GH3 cells were transfected via electroporation (Chatila et al., 1996; Sun et al., 1996) and HepG2 cells via lipofectamine (Norris et al., 1998) as previously described. In those experiments requiring stimulants, cells were allowed to recover from the initial transfection for 12–18 h and were subsequently treated with 0.67 μM ionomycin (Calbiochem) or 30 μM KN-93 (Calbiochem), or an equal volume of DMSO carrier. Cells were treated for 24 h and then harvested. Transfections were performed in triplicate for each condition tested on at least three different occasions.

Luciferase and CPRG assays

Cells were washed in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed on ice in lysis buffer [25 mM Tris–phosphate pH 7.8, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 mM 1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N, N, N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100] for 15 min. Cells were then scraped, transferred and spun at 15 000 g for 5 min. Supernatants were transferred and 20 μl aliquots were assayed in duplicate for luciferase activity as described by Doyle (1996). Readings were taken for 2 s/sample in a Labsystems Lumoskan Luminometer. Chlorophenol red-β-d-galactopyranoside (CPRG) assays were carried out in duplicate for each condition using 30 μl of cell lysate in 20 μl (4 mg/ml) of CPRG (Calbiochem) and 150 μl of CPRG buffer at 37°C for 12–18 h. Plates were read at 595 nm in a Labsystems Multiscan Platereader. Raw luciferase values were normalized for both transfection efficiency as determined by CPRG assay and cell number as determined by protein assay (Bio-Rad). Luciferase units are shown as (corrected) relative light units for a given condition performed in triplicate, with error bars indicating the standard deviation for that condition.

Protein expression

GST:RORLBD was transformed into BL21DE(3) competent cells (Novagen) and a 50 ml LB culture grown overnight in 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37°C. The next morning, the culture was diluted 1:20 in LB/ampicillin and grown at 37°C until OD 1.0, at which point isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.1 mM final concentration; Sigma) was added to the culture and grown for an additional 2 h at room temperature (20°C). The cells were pelleted and resuspended in lysis buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1.0 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1.5% sarkosyl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM DTT and 2 μg/ml aprotinin, leupeptin and pepstatin] on ice. Cells were lysed via sonication, centrifuged at 15 000 g and the supernatant removed. Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 3.3%, and the supernatant was added to glutathione–Sepharose beads (Pharmacia). GST:RORLBD and GST alone were purified via affinity chromatography at 4°C, washed extensively in lysis buffer (containing 0.5% NP-40 instead of sarkosyl) and then dialyzed in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0. Proteins were volume reduced via ultrafiltration and stored in 10% glycerol in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0. Analysis via SDS–PAGE showed that the protein was purified to >95% homogeneity. His-tagged 1–117:P300 was purified via affinity chromatography (as described above) using Ni–NTA–agarose (Qiagen), lysis buffer (5 mM imidazole pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.1% NP-40 and protease inhibitors) and washing buffer (60 mM imidazole pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0). Recombinant 1–117:P300 was eluted (400 mM imidazole pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0), dialyzed and concentrated as described above. GST:CaMKI and maltose-binding protein (MBP):KKB were purified using similar affinity techniques to those previously described (Haribabu et al., 1995; Anderson et al., 1998).

Kinase assay

GST:RORLBD and 1–117:P300 were used as substrates for in vitro kinase assays with recombinant CaMKI and CaMKKB. Briefly, 500 ng of GST:RORLBD or 1–117:P300 were incubated in kinase buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 40 mM MgCl2, 4 μM CaM, 8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM ATP, 0.1% Tween-20 and 2 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP/reaction) in either the absence or presence of 200 ng of recombinant GST:CaMKI and/or 500 ng MBP:CaMKKB for 20 min at 30°C. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 2× SDS–PAGE loading buffer and fractionated on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, stained with Coomassie Blue dye and dried on Whatman 3MM paper. The gel was then exposed in a phosphorimager cassette for 8 h and imaged with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to V.Giguère and D.McDonnell for graciously supplying many of the plasmids used throughout the course of this study. We would also like to thank B.O'Malley, A.Cooney, E.Cocoran and C.-Y.Chang for providing reagents used in this work, as well as the members of both the Means and McDonnell laboratories for their many helpful comments and discussions. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HD07503 and GM33976 to A.R.M. and NRSA F32AI0976464 to C.D.K.

References

- Anderson K.A. and Kane, C.D. (1998) Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV and calcium signaling. BioMetals, 11, 331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K.A., Ribar, T.J., Illario, M. and Means, A.R. (1997) Defective survival and activation of thymocytes in transgenic mice expressing a catalytically inactive form of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. Mol. Endocrinol., 11, 725–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K.A., Means, R.L., Huang, Q.-H., Kemp, B.E., Goldstein, E.G., Selbert, M.A., Edelman, A.M., Fremeau, R.T. and Means, A.R. (1998) Components of a calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade: molecular cloning, functional characterization and cellular localization of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 31880–31889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany Z., Newsome, D., Oldread, E., Livingston, D.M. and Eckner, R. (1995) A family of transcriptional adaptor proteins targeted by the E1A oncoprotein. Nature, 374, 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronica M. and Katzenellenbogen, B.S. (1993) Stimulation of estrogen receptor-mediated transcription and alteration in the phosphorylation state of the rat uterine estrogen receptor by estrogen, cyclic adenosine monophosphate and insulin-like growth factor-I. Mol. Endocrinol., 7, 743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunone G., Briand, P.-A., Miksicek, R.J. and Picard, D. (1996) Activation of the unliganded estrogen receptor by EGF involves the MAP kinase pathway and direct phosphorylation. EMBO J., 15, 2174–2183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Norris, J.D., Grøn, H., Paige, L.A., Hamilton, P.T., Kenan, D.J., Fowlkes, D. and McDonnell, D.P. (1999) Dissection of the LXXLL nuclear-co-activator interaction motif using combinatorial peptide libraries. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 8226–8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatila T., Anderson, K.A., Ho, N. and Means, A.R. (1996) A unique phosphorylation-dependent mechanism for the activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type IV/Gr. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 21542–21548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla S., Hardingham, G.E., Quinn, D.R. and Bading, H. (1998) CBP: a signal-regulated transcriptional coactivator controlled by nuclear calcium and CaM kinase IV. Science, 281, 1505–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrivia J.C., Kwok, R.P., Lamb, N., Hagiwara, M., Montminy, M.R. and Goodman, R.H. (1993) Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature, 365, 855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney A.J., Tsai, S.Y., O'Malley, B.W. and Tsai, M.J. (1992) Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF) dimer binds to different GGTCA responsive elements, allowing COUP-TF to repress hormonal induction of the vitamin D3, thyroid hormone and retinoic acid receptors. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 4153–4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle K., ed. (1996) Protocols and Applications Guide. Promega Corporation, pp. 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Dussault I., Fawcett, D., Matthyssen, A., Bader, J.-A. and Giguère, V. (1998) Orphan nuclear receptor RORα-deficient mice display the cerebellar defects of staggerer.Mech. Dev., 70, 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckner R., Ewen, M.E., Newsome, D., Gerdes, M., DeCaprio, J.A., Lawrence, J.B. and Livingston, D.M. (1994) Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the adenovirus E1A-associated 300-kD protein (p300) reveals a protein with properties of a transcriptional adapter. Genes Dev., 8, 869–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman B.M., Tzameli, I., Choi, H.-S., Chen, J., Simha, D., Seol, W., Evans, R.M. and Moore, D.D. (1999) Androstane metabolites bind to and deactivate the nuclear receptor CAR-β. Nature, 395, 612–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangakis M.V., Chatila, T., Wood, E.R. and Sahyoun, N. (1991) Expression of a neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase, CaM kinase-Gr, in rat thymus. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 17592–17596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giguère V., Tini, M., Flock, G., Ong, E., Evans, R.M. and Otulakowski, G. (1994) Isoform-specific amino-terminal domains dictate DNA-binding properties of RORα, a novel family of orphan hormone nuclear receptors. Genes Dev., 8, 538–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giguère V., McBroom, L.D.B. and Flock, G. (1995) Determinants of target gene specificity for RORα1: monomeric DNA binding by an orphan nuclear receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 2517–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez G.A. and Montminy, M.R. (1989) Cyclic AMP stimulates somatostatin gene transcription by phosphorylation of CREB at serine 133. Cell, 59, 675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göttlicher M., Widmark, E., Li, Q. and Gustafsson, J.-A. (1992) Fatty acids activate a chimera of the clofibric acid-activated receptor and the glucocorticoid receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 4653–4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastavino J.M. and Larsson, K. (1992) The staggerer gene curtails the reproductive life span of females. Behav. Genet., 22, 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton B.A., et al. (1996)Disruption of the nuclear hormone receptor RORα in staggerer mice. Nature, 379, 736–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding H.P., Atkins, G.B., Jaffe, A.B., Seo, W.J. and Lazar, M.A. (1997) Transcriptional activation and repression by RORα, an orphan nuclear receptor required for cerebellar development. Mol. Endocrinol., 11, 1737–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haribabu B., Hook, S.S., Selbert, M.A., Goldstein, E.G., Tomhave, E.D., Edelman, A.M., Snyderman, R. and Means, A.R. (1995) Human calcium–calmodulin dependent protein kinase I: cDNA cloning, domain structure and activation by phosphorylation at threonine-177 by calcium–calmodulin dependent protein kinase I kinase. EMBO J., 14, 3679–3686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heery D.M., Kalkhoven, E., Hoare, S. and Parker, M.G. (1997) A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature, 387, 733–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman R.A., Mangelsdorf, D.J., Dyck, J.A., Stein, R.B., Eichele, G., Evans, R.M. and Thaller, C. (1992) 9-cis retinoic acid is a high affinity ligand for the retinoid X receptor. Cell, 68, 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H., Kohli, K., Trivedi, A., Johnson, D.L. and Stallcup, M.R. (1996) GRIP1, a novel mouse protein that serves as a transcriptional coactivator in yeast for the hormone binding domains of steroid receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 4948–4952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu E., Kim, J.B., Sarraf, P. and Spiegelman, B.M. (1996) Inhibition of adipogenesis through MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation of PPARγ. Science, 274, 2100–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K.F., Ohmstede, C.A., Fisher, R.S. and Sahyoun, N. (1991) Nuclear and axonal localization of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type Gr in rat cerebellar cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 2850–2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau P., Bailey, P., Dowhan, D.H. and Muscat, G.E.O. (1999) Exogenous expression of a dominant negative RORα1 vector in muscle cells impairs differentiation: RORα1 directly interacts with p300 and MyoD. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makishima M., et al. (1999)Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science, 284, 1362–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews R.P., Guthrie, C.R., Wailes, L.M., Zhao, X., Means, A.R. and McKnight, G.S. (1994) Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases type II and type IV differentially regulate CREB-dependent gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 6107–6116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBroom L.D., Flock, G. and Giguère, V. (1995) The nonconserved hinge region and distinct amino-terminal domains of the RORα orphan nuclear receptor isoforms are required for proper DNA bending and RORα–DNA interactions. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 796–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means A.R., ed. (1995) Calcium Regulation of Cellular Function. Raven Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Means A.R., Cruzalegui, F., LeMagueresse, B., Needleman, D.S., Slaughter, G.R. and Ono, T. (1991) A novel Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase and a male germ cell-specific calmodulin-binding protein are derived from the same gene. Mol. Cell. Biol., 11, 3960–3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev A., Yan, Z.-H., Hirose, T., Giguère, V. and Jetton, A.M. (1996) Cloning of a cDNA encoding the murine orphan receptor RZR/RORγ and characterization of its response element. Gene, 181, 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranti C.K., Ginty, D.D., Huang, G., Chatila, T. and Greenberg, M.E. (1995) Calcium activates serum response factor-dependent transcription by a Ras- and Elk-1-independent mechanism that involves a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 3672–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nghiem P., Ollick, T., Gardner, P. and Schulman, H. (1994) Interleukin-2 transcriptional block by the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin kinase. Nature, 371, 347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte R.T., et al. (1998)Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Nature, 395, 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J.D., Fan, D., Stallcup, M.R. and McDonnell, D.P. (1998) Enhancement of estrogen receptor transcriptional activity by the coactivator GRIP-1 highlights the role of activation function 2 in determining estrogen receptor pharmacology. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 6679–6688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmstede C.A., Jensen, K.F. and Sahyoun, N.E. (1989) Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase enriched in cerebellar granule cells. Identification of a novel neuronal calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 5866–5875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oñate S.A., Tsai, S.Y., Tsai, M.-J. and O'Malley, B.W. (1995) Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science, 270, 1354–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks D.J., et al. (1999)Bile acids: natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science, 284, 1365–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schräder M., Danielsson, C., Wiesenber, I. and Carlberg, C. (1996) Identification of natural monomeric response elements of the nuclear receptor RZR/ROR. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 19732–19736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman R.L., Lane,P.W. and Dickie,M.M. (1962) Staggerer, a new mutation in the mouse affecting the cerebellum. Science, 137, 610–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmayr M. et al. (1998) Staggerer phenotype in retinoid-related orphan receptor α-deficient mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 3960–3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P., Lou, L. and Maurer, R.A. (1996) Regulation of activating transcription factor-1 and the cAMP response element-binding protein by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases type I, II and IV. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 3066–3073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Sassone-Corsi, P. and Means, A.R. (1995) Calspermin gene transcription is regulated by two cyclic AMP response elements contained in an alternative promoter in the calmodulin kinase IV gene. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 561–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto G.S., Hovland, A.R., Tasset, D.M., Melville, M.Y., Tung, L. and Horwitz, K.B. (1996) Role of phosphorylation on DNA binding and transcriptional functions of human progesterone receptors. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 13308–13316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumitsu H., Enslen, H. and Soderling, T.R. (1995) Characterization of a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade. Molecular cloning and expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 19320–19324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchia J., Rose, D.W., Inostroza, J., Kamei, Y., Westin, S., Glass, C.K. and Rosenfeld, M.G. (1997) The transcriptional co-activator p/CIP binds CBP and mediates nuclear-receptor function. Nature, 387, 677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenkner E. and Hoffmann, M.K. (1986) Defective development of the thymus and immunological abnormalities in the neurological mouse mutation ‘staggerer’. J. Neurosci., 6, 1733–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel N.L. and Zhang, Y. (1998) Ligand-independent activation of steroid hormone receptors. J. Mol. Med., 76, 469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R.R., Young-Guen, K. and Taing, M. (1998) Definitions of optimal substrate recognition motifs of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV and II reveal shared and distinctive features. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 3166–3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtz J.-M., Bourguet, W., Renaud, J.-P., Vivat, V., Chambon, P., Moras, D. and Gronemeyer, H. (1996) A canonical structure for the ligand-binding domain of nuclear receptors. Nature Struct. Biol., 3, 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]