Abstract

As health systems strive to meet the needs of linguistically diverse patient populations, determining a physician’s non-English language proficiency is becoming increasingly important. However, brief, validated measures are lacking. To determine if any of four self-reported measures of physician Spanish language proficiency are useful measures of fluency in Spanish. Physician self-report of Spanish proficiency was compared to Spanish-speaking patients’ report of their physicians’ language proficiency. 110 Spanish-speaking patients and their 46 physicians in two public hospital clinics with professional interpreters available. Physicians rated their Spanish fluency with four items: one general fluency question, two clinically specific questions, and one question on interpreter use. Patients were asked if their doctor speaks Spanish (“yes/no”). Concordance, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV) were calculated for each of the items, and receiver operating (ROC) curves were used to compare performance characteristics. Concordance between physician and patient reports of physician Spanish proficiency ranged from 84 to 91%. The PPV for each of the four items ranged from 91 to 99%, the NPV from 60 to 90%, and the area under their ROC curves from 90 to 95%. The general fluency question gave the best combination of PPV and NPV, and the item on holding sensitive discussions had the highest PPV, 99%. Physicians who reported fluency as “fair” were as likely to have patients report they did not speak Spanish as that they did. Physician self-report of Spanish language proficiency is highly correlated with patient report, except when physicians report “fair” general fluency. In settings where no financial or other incentives are linked to language skills, simple questions may be a useful way to assess physician language proficiency.

Keywords: Limited English proficiency, Latino/Hispanic, Interpreter use, Physician-patient communication

Introduction

Latinos are the fastest growing segment of the US population, and there is growing evidence that for Latinos with limited English proficiency (LEP), language barriers negatively affect medical care. Receipt of tests, follow-up rates, medication prescription and adherence, recall, comprehension, and interpersonal processes of care are adversely affected when Spanish-speaking LEP patients cannot speak Spanish with their physicians [1–9]. Not surprisingly, Spanish-speaking patients often prefer to see Spanish-speaking physicians, and are more satisfied when they do [5, 10]. Many advocates believe that patients should be aware of a physician’s language proficiency when choosing a provider [11]. Health systems need to know the language capabilities of the physicians they employ when allocating resources for interpreter services. For these reasons it is increasingly important to measure the Spanish language proficiency of physicians.

However, no convenient, standardized measures of physician Spanish language proficiency exist. Some agencies administer written or oral tests which require considerable time and expense. Others rely on simple self-report of physician language proficiency, without knowing if this is a reliable measure. We compared physician self-report of Spanish language fluency to patient reports of physician proficiency to determine the accuracy of physician self-report.

Methods

Setting/Participants

The study was conducted in two primary care clinics at San Francisco General Hospital, the public hospital of the city and county of San Francisco, as part of a larger study of physician-patient communication in diabetes care [4, 12]. Patients in these clinics received care from University of California, San Francisco attending faculty and residents. All physicians in these clinics completed university and medical school in the US. Professional interpreter services were available on site from the hospital interpreter service department. Physician-patient dyads were identified by an electronic database based on criteria for the diabetes study. Details of the study and patient enrollment are described elsewhere [4]. One hundred and sixteen Latino patients with type two diabetes chose to complete the questionnaire in Spanish. Of these, six indicated they spoke English “well” or “very well” and were excluded from this study. Forty-two patients spoke English “not at all” and 68 spoke “not well”, and we defined these 110 patients as having limited English proficiency. These 110 LEP patients and their 46 primary care physicians composed our study sample.

Language Measures and Interpreter Use

We measured physician self-rated language proficiency with a self-administered, written questionnaire. Spanish language proficiency was assessed with four questions—one general fluency question, two clinically specific questions, and one question on interpreter use: (1) How would you rate your level of fluency in Spanish? (five point Likert response scale ranging from “excellent” to “none”). (2) Without the use of an interpreter, how confident are you that you can conduct a new patient history and physical with a monolingual Spanish-speaking patient? (four point scale ranging from “extremely confident” to “not confident”). (3) Without the use of an interpreter, how confident are you that you can discuss a complex and sensitive subject, such as sexually transmitted disease or the diagnosis of a terminal illness, with a monolingual Spanish-speaking patient? ( four point scale ranging from “extremely confident” to “not confident”). (4) How often do you use an interpreter (either staff or family member) when you see a monolingual Spanish-speaking patient? (five point scale ranging from “never” to “always”).

Patient measures were gathered through questionnaires administered by bilingual research assistants in face-to-face interviews. Patients’ perception of their physician’s Spanish language proficiency was measured by asking, “Does your doctor speak Spanish?” with a response option of “yes/no”.

To address the concern that patient response to “Does your physician speak Spanish” may represent a patient’s report of a physician’s effort rather than an assessment of proficiency, or may represent patient confusion about the role of an interpreter in an encounter, we conducted a post visit survey with a subset of the physicians. After the visit, physicians were asked: (1) What language do you usually speak with this patient? (2) In your opinion, is this patient fluent in English (“yes/no”)? (3) Did you use an interpreter (“yes/no”)? (4) Would you have preferred to use an interpreter for this patient (“yes/no”)? Results of this survey allowed us to compare patient reports of physician proficiency with what actually happened during the visit.

Analysis

We assessed concordance between physician report of language fluency and patient assessment of physician Spanish language proficiency, and calculated sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for each of the four self-reported measures of fluency. We dichotomized physician responses at two different points so as to compare the effect of grouping “fair” with “excellent/good” speakers versus with “poor/none” for the fluency question; and grouping “somewhat confident” with “extremely/very” versus with “not confident” for the two clinically specific questions. We generated receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to further compare the performance characteristics of the four items. Finally, to distinguish patient assessment of physician Spanish proficiency from report of Spanish language use or use of interpreter, we compared patient report to post-visit physician reports. SAS statistical software was used for all calculations [13].

Results

All physicians for the 110 Spanish-speaking LEP patients agreed to participate. Patients had a mean age of 59 years (SD = 12) and 71% were women. 78% had less than a high school education, only 3% had an income over $20,000 a year, and 90% were uninsured or publically insured. Most patients were in well-established physician-patient relationships: 35 (32%) had relationships of over 3 years, 53 (47%) between 1 and 3 years, and 22 (20%) between 6 months and 1 year. Study physicians (N = 46) were residents and faculty in family medicine (N = 18) or internal medicine (N = 28). Most were women (N = 28) and nine self-identified as Hispanic/Latino. Table 1 reports additional physician demographic characteristics as well as responses to the four items measuring Spanish language proficiency. Twenty-six (57%) physicians reported speaking “excellent” or “good” Spanish, while 13 (28%) reported “poor” or “no” Spanish.

Table 1.

Physician characteristics and self-report of Spanish language proficiency

| N = 46 physicians N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 35.3 (7.2) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 28 (61) |

| Men | 18 (39) |

| Level of training | |

| Resident | 29 (63) |

| Attending | 17 (37) |

| Specialty | |

| Internal medicine | 28 (61) |

| Family medicine | 18 (39) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Asian | 4 (9) |

| Black | 2 (4) |

| Latino | 9 (20) |

| White | 31 (67) |

| Fluency in Spanish | |

| Excellent | 12 (26) |

| Good | 14 (31) |

| Fair | 7 (15) |

| Poor | 6 (13) |

| None | 7 (15) |

| Confident performing history and physical in Spanish | |

| Extremely | 15 (32) |

| Moderately | 10 (22) |

| Somewhat | 4 (9) |

| Not confident | 17 (37) |

| Confident with sensitive discussion in Spanish | |

| Extremely | 10 (22) |

| Moderately | 10 (22) |

| Somewhat | 2 (4) |

| Not confident | 24 (52) |

| Use of Spanish interpreter | |

| Never | 15 (32) |

| Rarely | 9 (20) |

| Occasionally | 6 (13) |

| Usually | 4 (9) |

| Always | 12 (26) |

Table 2 shows the concordance, sensitivities, specificities and positive (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) for the four physician language items, using the two different dichotomization points for physician responses. Regardless of how we grouped responses, the PPV for all four questions was over 90%. The question assessing confidence conducting complex and sensitive discussions had the highest PPV (99%) as well as the highest specificity (96%). The NPV for the items varied considerably, from 60 to 90%, depending on how responses were dichotomized. For example, the NPV of the general fluency question went from 72 to 90% when “fair” was grouped with “excellent/good” rather than with “poor/none.”

Table 2.

Performance characteristics for four measures of self-reported physician Spanish language proficiency compared to patient report of physician Spanish language proficiency

| N = 110 encounters | Fluency in Spanish | Confident performing history and physical | Confident holding sensitive discussion | Use of Spanish interpreter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E/G vs. F/P/N | E/G/F vs. P/N | E/V vs. S/N | E/V/S vs. N | E/V vs. S/N | E/V/S vs. N | N/R vs. O/U/A | N/R/O vs. U/A | |

| Percent concordance | 88 | 91 | 86 | 89 | 84 | 86 | 88 | 87 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 89 | 98 | 87 | 92 | 80 | 83 | 92 | 86 |

| Specificity (%) | 85 | 70 | 85 | 81 | 96 | 96 | 78 | 93 |

| PPV (%) | 95 | 91 | 95 | 94 | 99 | 99 | 93 | 97 |

| NPV (%) | 72 | 90 | 68 | 76 | 60 | 65 | 75 | 68 |

PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value; A = always; E = excellent/extremely; F = fair; G = good; N = none/not/never; O = occasionally; P = poor; R = rarely; S = somewhat; U = usually; V = very

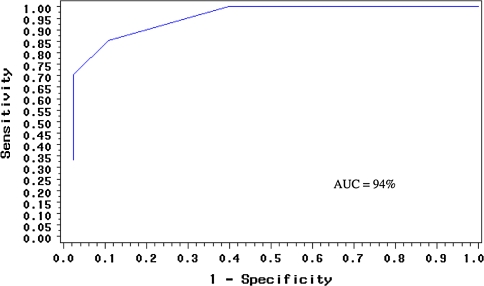

Figure 1 shows the receiver operating curves for the item on general fluency, “How would you rate your level of fluency in Spanish?” The area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC) was 94% (95% CI 89.7, 98.2%), indicating very good performance. The AUROCs for the two clinical questions and the one item on use of interpreters were similarly high, with values ranging from 90 to 95%.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for physician responses to the question: “How would you rate your level of fluency in Spanish?”

While patient physician concordance was high at the extremes of the general fluency scale, physicians who answered “fair” were as likely to have patients report that they did not speak Spanish as that they did speak Spanish. To further characterize the Spanish proficiency of the “fair” respondents (N = 11), we examined whether sequentially combining the general fluency question with either of the two clinical questions in a two-step test improved the performance of this response. Combining these questions did not improve performance over the use of the fluency question alone. For example, when an answer of “fair” was followed by “excellent/very confident” in “conducting a sensitive discussion”, the PPV decreased from 99 to 95%, and the NPV increased from 60 to 72%. We tested the possibility that this result was due to the small number of “fair” respondents by simulating a sample in which up to 50% of physicians answered “fair”, but this did not alter our results.

The post-visit questionnaire administered to a subset of physicians allowed us to directly compare patient report and physician experiences. In 41/46 (89%) encounters, patients and physicians agreed that the physician spoke Spanish during the encounter and the physician reported not wishing for an interpreter. In 5/46 encounters the patient reported the physician “spoke Spanish” yet in 3/5 the physician reported use of an interpreter, while in 2/5 the physician had spoken Spanish but wished he/she had used an interpreter.

Conclusions

This study addresses the lack of a reliable, convenient measure of physician Spanish language proficiency. We found that physician self-report of Spanish proficiency correlates well with patient’s assessment of physician fluency, regardless of whether proficiency is measured by a general fluency item, either of two clinically specific items, or a question on interpreter use. All of the items performed well when used independently, and combining the items did not improve their performance. When assessing physician Spanish fluency the general fluency item dichotomized at “excellent/good/fair” versus “poor/none” generated the best combination of high PPV and NPV. However, the clinically specific question on confidence conducting complex and sensitive discussions may be the most useful when higher specificity for complex discussions is desired, as is often the case in primary care where patients and physicians routinely discuss complex matters.

While this study did not address the question of how much Spanish proficiency is “good enough” [14], our previous work using the same measures of physician language proficiency found that the cut-point of “excellent/good” Spanish was associated with better patient reports of communication [4]. Taken together, these studies support the value of these physician language measures, including the general fluency question alone, and caution against ascribing clinical fluency to “fair” speakers. These physicians may be more likely to exhibit “false fluency,” using incorrect words or phrasing, which is associated with a higher likelihood of communication errors [15].

Our study has several limitations. It was conducted at two clinic sites in one public teaching hospital, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Although the hospital is representative of settings where many low-income Latino immigrants receive health care, results may not generalize to physicians with more affluent or more educated Spanish-speaking patients, to sites without access to professional interpreters, to other languages, or to non-physician clinicians. Low-income patients may be particularly disinclined to “criticize” their physician. In addition, our data were gathered in a research context in which physicians were under no financial or other incentive to either inflate or diminish their Spanish-speaking abilities. Physician self-report of language proficiency may be less reliable if financial or other incentives are tied to responses.

This study used patient responses to the question “Does your doctor speak Spanish” as the “gold standard” against which we compared physician self-reports. Our results suggest that with few exceptions, patients were able to differentiate physician Spanish effort from Spanish proficiency, and did not confuse the presence of an interpreter with fluency. However, we recognize that the dichotomous response option of “yes/no” is not sufficient to capture clinical proficiency. More research with more detailed and nuanced capture of patient experience is needed. While we believe that the patient experience is the right standard for evaluating the adequacy of physician skills, further studies that relate the results of external examinations, such as formal language testing, to patient reports’ of clinician fluency are needed [16]. It is also important to note that fluency, or clinician language competence, is situational and while language skills may be adequate in one clinical setting, they may not be sophisticated enough for another [14, 17].

We have described the performance characteristics of simple measures for assessing physician Spanish language proficiency. If confirmed through research in other settings and by capture of more nuanced reports from patients, these measures will be useful for patients in selecting physicians to optimize language concordance, and by planners anticipating the need for interpreters. As the US becomes increasingly diverse and the number of LEP patients increases, we need better ways of ensuring physicians and patients can communicate effectively. Measuring the language capabilities of physicians represents an important first step in this process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kevin Grumbach and colleagues in the Primary Care Research Center at San Francisco General Hospital for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Funding for this study was provided to Dr. Fernandez by grant K23 RR18324 and to Dr. Schillinger by grant UL1 RR024131.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Anne Rosenthal, Phone: +1-415-2921300, FAX: +1-415-9286487, Email: arosenthal@medsfgh.ucsf.edu.

Frances Wang, Phone: +1-919-6841837, Email: frances.wang@duke.edu.

Dean Schillinger, Phone: +1-415-2068940, FAX: +1-415-2065586.

Eliseo J. Pérez Stable, Phone: +1-415-5024008, Email: eliseops@medicine.ucsf.edu

Alicia Fernandez, Phone: +1-415-2065394, Email: afernandez@medsfgh.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Weech-Maldonado R, Elliott MN, Morales LS, Spritzer K, Marshall GN, Hays RD. Health plan effects on patient assessments of medicaid managed care among racial/ethnic minorities. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):136–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Baker DW, Hayes R, Fortier JP. Interpreter use and satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of care for Spanish-speaking patients. Med Care. 1998;36(10):1461–1470. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrasquillo O, Orav EJ, Brennan TA, Burstin HR. Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an emergency department. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(2):82–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Grumbach K, et al. Physician language ability and cultural competence. An exploratory study of communication with Spanish-speaking patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):167–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Morales LS, Cunningham WE, Brown JA, Liu H, Hays RD. Are Latinos less satisfied with communication by health care providers? J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(7):409–417. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.06198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Stable EJ, Napoles-Springer A, Miramontes JM. The effects of ethnicity and language on medical outcomes of patients with hypertension or diabetes. Med Care. 1997;35(12):1212–1219. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarver J, Baker DW. Effect of language barriers on follow-up appointments after an emergency department visit. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(4):256–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Schenker Y, Wang F, Selig SJ, Ng R, Fernandez A. The impact of language barriers on documentation of informed consent at a hospital with on-site interpreter services. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):294–299. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0359-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):800–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Gany F, Leng J, Shapiro E. Patient satisfaction with different interpreting methods: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):312–318. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shelton L, Aiuppa L, Torda P. Recommendations for improving the quality of physician directory information on the internet. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.SAS version 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 1999.

- 14.Ferguson WJ. Un poquito. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(6):1695–700.

- 15.Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, et al. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):6–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Moreno MR, Otero-Sabogal R, Newman J. Assessing dual-role staff-interpreter linguistic competency in an integrated healthcare system. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):331–335. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0344-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schenker Y, Lo B, Ettinger KM, Fernandez A. Navigating language barriers under difficult circumstances. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(4):264–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]